Abstract

Visual perception is one of the core technologies for achieving unmanned and intelligent mining in underground mines. However, the harsh environment unique to underground mines poses significant challenges to visible light-based visual perception methods. Multimodal fusion semantic segmentation offers a promising solution, but the lack of dedicated multimodal datasets for underground mines severely limits its application in this field. This work develops a multimodal semantic segmentation benchmark dataset for complex underground mine scenes (MUSeg) to address this issue. The dataset comprises 3,171 aligned RGB and depth image pairs collected from six typical mines across different regions of China. According to the requirements of mine perception tasks, we manually annotated 15 categories of semantic objects, with all labels verified by mining experts. The dataset has also been evaluated using classical multimodal semantic segmentation algorithms. The MUSeg dataset not only fills the gap in this field but also provides a critical foundation for research and application of multimodal perception algorithms in mining, contributing significantly to the advancement of intelligent mining.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Mineral resources serve as a material foundation for the development of human society. According to statistics, over 95% of global energy, 80% of industrial raw materials, and 70% of agricultural inputs depend on mineral resources. Based on deposit depth and techno-economic feasibility, non-oil/gas mineral resources are primarily extracted through two mining methods: surface mining and underground mining1. In China, non-oil/gas mineral resources are mainly extracted through underground mining, accounting for roughly 87% of coal production2 and 89% of non-ferrous metal production3. However, as operational depth can reach several hundred meters or even kilometers, underground mining faces multiple challenges, including complex and harsh environments, high risks of disasters, and significant difficulties in accident rescue operations4, all of which pose serious threats to the safety and health of workers. Therefore, promoting unmanned intelligent mining has become an urgent demand for industry development5,6.

One of the key technologies for intelligent mining is the perception of mine environments7,8. Among these, visual perception stands as the most critical sensing modality. The rapid advancement of mining visual sensor technology has enabled data-driven visual perception in mine environments9. As one of the core research directions in visual perception, image semantic segmentation10,11,12,13 assigns category labels to each pixel in an image while accurately predicting target objects’ positions and shapes. The pixel-level semantic information it provides serves as the critical foundation for intelligent robots to achieve scene understanding14, navigation and obstacle avoidance15, as well as task planning16. However, the underground mine environments (Fig. 1) are significantly more complex than surface environments, with highly variable lighting and narrow, congested layouts. These harsh conditions severely limit visible light-based semantic segmentation in mines, leading to low accuracy and poor robustness. With the rapid development of sensor technology, diverse visual sensors make complex scene perception achievable. For instance, infrared cameras17 can capture clear images in complete darkness or low-light conditions; depth cameras18 can provide precise distance measurement between the object and the camera. Therefore, multimodal fusion provides an effective solution for improving semantic segmentation in underground mines by leveraging complementary visual modalities.

In recent years, deep learning-based multimodal semantic segmentation methods have attracted extensive attention and achieved remarkable progress in other surface industries19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. However, when directly applied to mine data, these models exhibit severe deficiencies, including missing categories and recognition failures. To validate this issue, we selected Cityscapes27, an autonomous driving multimodal dataset with a category distribution similar to that of underground mines, as a benchmark dataset, and used the representative multimodal semantic segmentation model CMX20 for experiments. Specifically, we trained the CMX model separately on the Cityscapes dataset and underground mine data, with all validation conducted on the mine data. As shown in Fig. 2, although the model demonstrates stable performance on the Cityscapes dataset, severe performance degradation occurs when directly transferred to the mine data. The performance gap originates from intrinsic disparities between underground and surface environments. Mining equipment exhibits high specialization, requiring designs that meet both specialized operational processes and safety standards, resulting in significantly distinct appearances compared to surface equipment. Moreover, underground conditions are more complex and dynamic than surface conditions. Therefore, building a multimodal dataset for underground mines is crucial to improve the applicability of multimodal segmentation models in underground mines.

With depth cameras widely used, depth information has become an essential complement to visible-light visual perception28,29. Compared to visible-light images, depth information offers distinct advantages30, including lighting independence, rapid data acquisition, and high measurement accuracy, which can effectively address the challenges of severe lighting unevenness and insufficient texture information in underground mines. Currently, RGB-D datasets have been widely used in areas such as indoor robotics and autonomous driving. Among them, the NYU Depth V2 dataset31 contains 1,449 RGB-D images covering 40 semantic categories of indoor scenes. The SUN-RGBD dataset32 provides 10,335 RGB-D images annotated with 37 indoor scene categories. The Cityscapes dataset27 includes 2,975 training and 500 validation RGB-D images with dense semantic annotations across 33 classes. These multimodal datasets have garnered significant attention from both academia and industry, advancing research in multimodal fusion-based semantic segmentation methodologies. However, there remains a notable lack of RGB-D semantic segmentation datasets specifically designed for underground mines. Therefore, we deployed Microsoft Azure Kinect DK to capture aligned RGB and depth images in diverse underground mine areas to build a multimodal semantic segmentation dataset for complex underground mine scenes (MUSeg). The proposed dataset provides fundamental support for multimodal fusion-based semantic segmentation research in underground mines, facilitating the realization of critical tasks including intelligent robotic environmental perception, autonomous navigation, and independent operation in mining applications.

Methods

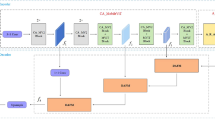

As shown in Fig. 3, the pipeline of our proposed multimodal semantic segmentation dataset comprises four critical stages: data collection, data filtering, data annotation, and data analysis, ensuring the quality and reliability of the final dataset.

Data collection

We selected Microsoft Azure Kinect DK throughout data acquisition. This device is widely used in major RGB-D datasets like NYU Depth V2 and SUN RGB-D. To address these challenges of intense lighting variations and confined tunnel conditions in mines, sensor parameters are configured according to Table 1. This sensor enables synchronous acquisition of spatially aligned RGB and depth images. Based on this, we designed an interactive acquisition system to overcome challenges, including motion blur and restricted depth measurement range. The system provides a real-time preview interface for data collectors to monitor the quality of RGB images and depth images simultaneously. Based on the preview results, operators can manually trigger single data capture to ensure data quality.

Although underground mines follow strict design standards, creating consistent internal layouts, factors such as mine type, production scale of mine, production start time, and geological conditions still significantly affect actual mine conditions, resulting in distinct environmental characteristics across mines. Therefore, we established eight selection factors and accordingly selected six representative mines based on these standards. Table 2 shows the eight basic information for each mine. Specifically, mine type determines the differences in equipment configuration and roadway structure between coal mines and non-coal mines; Production scale of mine not only affects spatial density of mine environments and production system configurations (including transportation, ventilation, drainage, etc.), but also reflects the infrastructure level of mines; Production start time reflects generational characteristics of mining technology, shown in significant differences in support methods, mining and heading equipment, and monitoring techniques; the function of a mine fundamentally shapes the specificity of its environment: operational mines present actual working environments, while training mines contain teaching-specific elements; the average burial depth determines roadway support structure design and layout scheme by influencing underground in-situ stress distribution; thickness of coal seam affects mining techniques, thereby further determining mining and heading equipment selection and mine structural configuration; geological conditions directly impact roadway deformation, for example, slope deformation may lead to increased textural complexity. These factors together lead to the diversity of characteristics in mine environments. Based on these eight key factors, we developed a dataset covering typical semantic features of various mines, thus significantly enhancing its diversity and applicability.

To further improve data richness and diversity, we selected four fundamental scene types (shafts, roadways, working faces, and chambers) for raw data collection. Table 3 shows the sub-scenes collected from each mine across the four fundamental scene types. Notably, roadways serve as the main passages connecting functional zones, ensuring personnel and material flow, and exhibit representative characteristics. They typically represent both the mine’s overall layout and its detailed spatial structures and environmental features. Therefore, due to safety regulations and site conditions, we prioritized roadway data collection for some mines to enhance dataset diversity.

Based on different mine factors and operational scenarios, our data covers: diverse equipment types and layouts, variable support structures, significant light variations (from darkness to bright conditions), and interference factors like equipment damage and dust accumulation, which collectively constitute the visual diversity in mines.

Data filtering

The raw data exhibited inconsistent quality, introducing interference in dataset annotation and construction. Considering the multimodal features of the dataset, we established corresponding filtering rules and processed the raw data accordingly. These rules are defined as: (1) absence of detectable targets in any modality; (2) motion blur present in RGB images; (3) depth images with less than 40% valid data points when the corresponding RGB images have a mean pixel intensity below 40. Furthermore, we performed manual verification and adjustment of the filtered results to better align with research requirements. Due to various noise interference factors in mine environments, partial information loss within modal data is one of the primary challenges for multimodal fusion technology in underground mines. For instance, the depth image may have missing data due to interference while the RGB image remains clear, or the RGB image may be dim while depth data stays reliable. We retained such RGB-D cases in the dataset to support robustness research for multimodal fusion models under partial modality missing conditions.

To maximize data utilization and optimize dataset quality, we performed refined processing on these data. For data from the same shooting location, we adopted different strategies based on scene complexity: for simple scenes (with no more than two distinct targets), we removed redundant views to improve data quality; for complex scenes (with more than two distinct targets or intricate structures), we retained some multi-view samples to enhance data richness. To avoid evaluation bias from similar multi-view samples, we used systematic file naming to group data from the same location. All data from the same group are consistently assigned to either the training set or test set, preventing data leakage.

Based on the aforementioned filtering and grouping strategies, we finally built the MUSeg dataset. Table 4 shows the data distribution from each mine, including 1,916 location groups with a total of 3,171 valid data pairs.

Data annotation

Since Azure Kinect DK’s depth images are only valid in the central hexagonal area, we first preprocessed the entire dataset: We identified a rectangle fitting within the hexagon. Then we uniformly cropped both RGB and depth images (originally 2048 × 1536) to this rectangular area, resulting in a final resolution of 1082 × 932. All further processing used these cropped images.

To improve annotation quality and efficiency, we used the open-source annotation tool ISAT-SAM for dataset annotation. ISAT-SAM is an image segmentation annotation tool that combines manual annotation and automatic annotation capabilities based on the SAM33 (Segment Anything Model). During the annotation process, we observed that the SAM’s target recognition performance was unsatisfactory for underground mine images with complex lighting conditions and weakened texture features. According to our preliminary statistics, 65% of target objects could not be accurately segmented by SAM, requiring manual annotation. This situation also indirectly demonstrates both the necessity and the challenges of constructing the dataset. Additionally, we designed a multimodal annotation strategy to solve the annotation difficulties of low-light RGB images in the dataset. Specifically, for normal-light images, we used RGB images for annotation. For low-light RGB images, we used corresponding depth images for annotation.

To further enhance data diversity, our dataset’s object annotations cover critical categories including infrastructure, mobile targets, and safety installations, with each category comprising multiple entities collected from different mines and various equipment types. Considering the insufficient research on multimodal semantic segmentation datasets for underground mines, we established a new semantic classification system with 15 categories, including: person, cable, tube, indicator, metal fixture, container, tools & materials, door, electrical equipment(e.g., transformers, motors), electronic equipment (e.g., controllers, sensors), mining equipment, anchoring equipment, support equipment, rescue equipment, and rail area. The design of categories is based on the requirements for scene understanding, intelligent navigation, and autonomous operation perception tasks of robots in underground mines, while fully summarizing and refining the target distribution characteristics of mine environments.

Quality control

The entire annotation process was guided and supervised by two professionals. Before annotating, we invited domain experts to establish clear annotation guidelines and provide relevant training to annotators.

In the initial annotation phase, we split images into batches for parallel annotation by six annotators. Each image was independently annotated by two annotators and concurrently checked by two experts. If the annotation result is unsatisfactory, we reject it and redo the annotation. Annotating each image takes about 20 minutes due to scene complexity. After initial annotation, three experts would cross-check the results, verifying category accuracy and layer positioning. This quality control ensures accurate annotations and categories.

Data analysis

After annotation, we evaluated the MUSeg dataset’s quality and features from multiple dimensions. Figure 4 (left panel) shows representative samples arranged left to right: RGB image, depth image, and label map. To ensure clear category distinctions, each semantic class is assigned a unique color as shown in the right panel of Fig. 4. Based on the annotation results, we analyzed pixel/instance distribution, scene complexity, and light intensity distribution to check label quality and key features of the MUSeg dataset.

First, we counted pixels and instances (annotated polygons) for each category. Figure 5(a) shows the instance distribution of 15 categories. Specifically, the Cable category has over 10,000 instances. Six categories (Tube, Indicator, etc.) range from 1,000 to 10,000 instances. Eight categories (Person, Door, etc.) range from 100 to 1,000 instances. Figure 5(b) shows the total pixel distribution. The results indicate that the total annotated pixels account for about 50% of the total image pixels, with most categories reaching around hundreds of millions of pixels.

To further evaluate the annotation complexity of the MUSeg dataset, we counted the different semantic categories in each image. As shown in Fig. 6(a), most images in the MUSeg dataset contain multiple semantic categories, with 76.41% of the total samples (2,423 images) containing three or more semantic categories.

Moreover, the MUSeg dataset specifically focuses on the actual features of underground mines. Significant light variations (from darkness to bright conditions) are one of the typical challenging features. To analyze lighting differences, we calculated the grayscale mean of each RGB image, then grouped values into 20-unit intervals (values > 120 were merged into the 120 interval) to analyze the brightness distribution of images. As shown in Fig. 6(b), the MUSeg dataset exhibits an overall low brightness profile, posing challenges for segmentation models.

Data Records

The MUSeg dataset is open to the public and released on the Figshare database34. To enable researchers to select different mine data according to practical needs, the dataset files adopt the hierarchical file organization structure shown in Fig. 7. The root directory contains 6 subfolders (one per mine, numbered as in Table 2) and experimental files. Under each mine subdirectory, data is stored by type: The Image folder stores RGB images (file format: JPG, resolution: 1082 × 932); The Depth folder stores depth images (file format: PNG, resolution: 1082 × 932, each pixel contains actual distance information, specific technical details refer to the official Microsoft Azure Kinect DK documentation); The Label folder stores multi-category annotation files, including: Colored Label with suffix ‘_color’ (file format: PNG, resolution: 1082 × 932), labels with suffix ‘_label’ (file format: PNG, resolution: 1082 × 932, each pixel’s value represents the corresponding category), annotation files with suffix ‘_polygons’ (file format: JSON, following Labelme standard).

All files follow a naming convention: <MM>-<RR>-<DD>-<GGGG>-<YYMMDDHHMMSS>-<BB>-<RR>.<EXT>

where <MM> stands for the mine number (01–06); <DD> stands for the acquisition device; <GGGG> stands for the data group number (matching the grouping strategy in Methods); <YYMMDDHHMMSS> stands for the collection timestamp; <BB> stands for the RGB image brightness level; <RR> stands for the reserved extension field; <EXT> stands for the file extension (JPG/PNG/JSON). Note: Certain fields use some fixed values to maintain a naming framework for future dataset expansion.

Technical Validation

Model selection

To better evaluate the feasibility of the MUSeg dataset, we designed a progressive experimental scheme ranging from single-modal to multimodal approaches. First, we selected two RGB semantic segmentation networks, DeeplabV3+35 and SegFormer36, to evaluate RGB-modal segmentation performance. To explore the effectiveness of depth information, we extended SegFormer with two variants: depth-only input and RGB-D fusion. The dual-modal version keeps the RGB backbone but adds a parallel depth branch, using weighted feature fusion for predictions. Finally, we selected four state-of-the-art open-source RGB-D semantic segmentation networks: SA-Gate19, DFormer21, CMX20, and CMNeXt22.

All experiments were run on dual NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPUs. Since SegFormer requires modifications, we used custom code instead of the official implementation, with all code uploaded to Figshare alongside the dataset. DeeplabV3+, SA-Gate, Dformer, CMX, and CMNeXt are validated using their official implementations with default configurations. To fit our dataset, we adjusted key settings: input size is set to 640 × 480 for GPU memory efficiency, and batch size varies by model size. The dataset is split into a training set (1,595 samples) and a test set (1,576 samples), with the split files uploaded to Figshare. Some models only accepted HHA format as depth input, so we performed the conversion using publicly available scripts. We set 500 epochs for all models. Three separate runs (different seeds only) were performed per model, averaging results for reliability.

Evaluation metrics

We evaluate segmentation performance using three standard metrics: Pixel Accuracy (PA), Mean Pixel Accuracy (MPA), and Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), defined as follows:

where TP, FP, and FN stand for true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively, and C is the total number of classes.

Results analysis

Table 5 shows the quantitative results of all models on the MUSeg dataset. From the results, most multimodal models show stable performance, confirming the effectiveness of our dataset. On the whole, multimodal models perform better than single-modal models. This phenomenon demonstrates that multimodal fusion holds clear advantages in underground scenes, better capturing their diversity and complexity.

Figure 8 shows representative qualitative results from the four multimodal models. The results demonstrate that the depth information can improve object segmentation in low-light environments while also boosting performance for cluttered objects in normal lighting.

Code availability

The MUSeg dataset34 has been released on Figshare under a CC BY 4.0 license and is freely accessible to researchers. The code comprises two components: data preprocessing and model validation. Data preprocessing mainly includes the following key steps: (1) Raw image cropping: Based on the characteristics of the hexagonal valid region in the depth map, the original 2048 × 1536 images are uniformly cropped to 1082 × 932 by manually calibrated rectangular frames to remove invalid boundary areas and enhance data consistency and validity; (2) Visualization interface: Professionals use the visualization script to strictly execute screening according to the criteria defined earlier, ensuring data quality meets the set requirements; (3) Valid pixel statistics of depth maps: Calculate the proportion of non-zero pixels image by image and generate reports, providing reliable references for subsequent image analysis. The relevant processing scripts are stored in the Processing folder of the database. We validated the dataset using multiple open-source semantic segmentation models, including DeeplabV3+, SegFormer, SA-GATE, CMX, DFormer, and DELIVERY. For SegFormer, the single-modal models, modified dual-modal models, and training/validation scripts are available in the Experiment folder of the dataset. For DeeplabV3+, we used a community PyTorch implementation (https://github.com/bubbliiiing/deeplabv3-plus-pytorch). For SA-GATE, CMX, DFormer, and DELIVERY, source codes are available in their original papers, with deployment instructions in their READMEs. The HHA format conversion script is available at https://github.com/charlesCXK/Depth2HHA-python. Researchers can perform conversion using the CameraInformation.txt file provided in our data repository. The annotation tool ISAT-SAM is available at its official website (https://github.com/heartexlabs/labelImg). Usage instructions can be found in the tool’s README documentation.

References

Hustrulid, W. A. & Bullock, R. L. Underground Mining Methods: Engineering Fundamentals and International Case Studies (SME, 2001).

Liu, X., Li, L. & Yang, Y. Development status of coal mining in China. South. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 123, 19–28 (2023).

Li, W. & Wang, X. Advances and research directions in mining technology for underground metal mines. Metall. Mater. 44, 175–177 (2024).

Ranjith, P. G. et al. Opportunities and challenges in deep mining: a brief review. Engineering. 3, 546–551 (2017).

Ge, S. et al. Making standards for smart mining operations: intelligent vehicles for autonomous mining transportation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 7, 413–416 (2022).

Wang, G. et al. Research and practice of intelligent coal mine technology systems in China. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 9, 24 (2022).

Ge, S., Hu, E. & Pei, W. Classification system and key technology of coal mine robot. J. China Coal Soc. 45, 455–463 (2020).

Ma, H. et al. Key technologies of intelligent mining robot. J. China Coal Soc. 49, 1174–1182 (2024).

Du, Y., Zhang, H., Liang, L., Zhang, J. & Song, B. Applications of machine vision in coal mine fully mechanized tunneling faces: a review. IEEE Access. 11, 102871–102898 (2023).

Long, J., Shelhamer, E. & Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 3431–3440 (2015).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III 18, 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Wang, J. et al. Real-time semantic segmentation for underground mine tunnel. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 133, 108269 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. An Efficient Large Kernel Convolution Network Designed for Neural Processing Unit. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 142, 109887 (2025).

Huang, C., Mees, O., Zeng, A. & Burgard, W. Visual language maps for robot navigation. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 10608–10615 (2023).

Yuan, X. & Chen, S. SAD-SLAM: A visual SLAM based on semantic and depth information. In 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 4930–4935 (2020).

Wang, Z., Tian, G. & Shao, X. Home service robot task planning using semantic knowledge and probabilistic inference. Knowl.-Based Syst. 204, 106174 (2020).

He, Y. et al. Infrared machine vision and infrared thermography with deep learning: a review. Infrared Phys. Technol. 116, 103754 (2021).

Horaud, R., Hansard, M., Evangelidis, G. & Ménier, C. An overview of depth cameras and range scanners based on time-of-flight technologies. Mach. Vis. Appl. 27, 1005–1020 (2016).

Chen, X. et al. Bi-directional cross-modality feature propagation with separation-and-aggregation gate for RGB-D semantic segmentation. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 561–577 (Springer, 2020).

Zhang, J. et al. CMX: Cross-modal fusion for RGB-X semantic segmentation with transformers. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24, 14679–14694 (2023).

Yin, B. et al. DFormer: Rethinking RGBD representation learning for semantic segmentation. ICLR (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Delivering arbitrary-modal semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 1136–1147 (2023).

Kim, M., Gao, S., Hsu, Y. C., Shen, Y. & Jin, H. Token fusion: Bridging the gap between token pruning and token merging. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 1383–1392 (2024).

Jia, D. et al. GeminiFusion: Efficient pixel-wise multimodal fusion for vision transformer. ICML (2024).

Srivastava, S. & Sharma, G. Omnivec2: A novel transformer based network for large scale multimodal and multitask learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 27412–27424 (2024).

Huang, J. et al. Roadformer+: Delivering RGB-X scene parsing through scale-aware information decoupling and advanced heterogeneous feature fusion. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. (2024).

Cordts, M. et al. The Cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 3213–3223 (2016).

Cao, J. et al. ShapeConv: Shape-aware convolutional layer for indoor RGB-D semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 7088–7097 (2021).

Seichter, D., Köhler, M., Lewandowski, B., Wengefeld, T. & Gross, H. M. Efficient RGB-D semantic segmentation for indoor scene analysis. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 13525–13531 (2021).

Wang, C., Wang, C., Li, W. & Wang, H. A brief survey on RGB-D semantic segmentation using deep learning. Displays. 70, 102080 (2021).

Silberman, N., Hoiem, D., Kohli, P. & Fergus, R. Indoor segmentation and support inference from RGB-D images. In Computer Vision - ECCV 2012: 12th European Conference on Computer Vision, Florence, Italy, October 7-13, 2012, Proceedings, Part V 12, 746–760 (2012).

Song, S., Lichtenberg, S. P. & Xiao, J. SUN RGB-D: A RGB-D scene understanding benchmark suite. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 567–576 (2015).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 4015–4026 (2023).

Li, S. et al. MUSeg: A multimodal semantic segmentation dataset for complex underground mine scenes. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28749098 (2025).

Chen, L. C., Zhu, Y., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F. & Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision, 801–818 (2018).

Xie, E. et al. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 12077–12090 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52121003, 62372453). The authors gratefully acknowledge the mining companies for their support in data acquisition, as well as all contributors involved in dataset development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shiyan Li is responsible for overall framework design, data collection, data annotation, technical validation of the dataset, and manuscript drafting. Qingqun Kong is responsible for framework supervision and manuscript revision. Xuan Gao, Fangzhen Shi, Penghao Wang are responsible for data annotation, data management, and technical validation of the dataset. Lianghui Li is responsible for data collection, annotation verification, and reviewing the accuracy of professional content. Qi Zhang takes charge of the manuscript revision. Kehu Yang is responsible for supervision, project management, and funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Kong, Q., Gao, X. et al. MUSeg: A multimodal semantic segmentation dataset for complex underground mine scenes. Sci Data 12, 1160 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05493-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05493-9