Abstract

The longhorn beetle Arhopalus rusticus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) is a widely distributed wood-boring pest of conifers. Here, we assembled a chromosome-level genome of A. rusticus using Illumina, Oxford Nanopore, and Hi-C sequencing technologies. The assembled genome is 1180.40 Mb, with a scaffold N50 of 125.01 Mb, and BUSCO completeness of 93.6%. All contigs were assembled into ten pseudo-chromosomes. The genome contains 69.87% repeat sequences. We identify 18, 377 protein-coding genes in the genome, of which 11,368 were functionally annotated. This genome provides a valuable resource for understanding the ecology, genetics, and evolution of A. rusticus, as well as for controlling wood-boring pests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The longhorn beetle Arhopalus rusticus (Linnaeus) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae: Aseminae: Arhopalus) is a wood-boring pest of conifers, mainly pine and spruce1,2. Its native distribution includes Europe and Asia3. In recent years, this species has been introduced to Argentina, the United States, Mexico, Australia, and New Zealand1,4,5,6. The A. rusticus tends to feed on weak or dead trees, and shallow roots7,8, especially the dead trees left standing after a fire9,10,11. The larvae bore into the trunk, creating irregular galleries, accelerating decay, and affecting the value of wood12,13. It not only damages host plants but also threatens timber materials during transport. This pest has been intercepted at multiple Chinese ports. Historical interception records confirm its passive dispersal via wood packaging materials, posing a potential threat to forestry ecological security. Well-assembled genomes provide invaluable resources to understand the biology, ecology and evolution of A. rusticus14. Currently, genomes of Cerambycidae have been reported for Anoplophora glabripennis15, Monochamus alternatus16, and Monochamus saltuarius17, but, there is no assembled genome for A. rusticus. Bridging this knowledge gap will greatly aid control efforts against A. rusticus.

In this study, we assembled a chromosome-level genome of A. rusticus using a combination of Oxford Nanopore long-read, Illumina short-read sequencing, and chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technologies to provide genomic resources for future investigations and pest management.

Methods

Sample preparation

Samples of A. rusticus were collected from the Double Island Forest Farm in Weihai, Shandong province. A single female adult was used to construct libraries of Illumina, Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT), and Hi-C sequencing. Samples were starved for 24 hours, and the guts were removed to minimize contamination from gut microbes. Additionally, we collected three replicates of larvae, pupae, and adults for transcriptome sequencing. All samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C before usage.

Genomic DNA sequencing

For short-read sequencing, genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method, followed by purification using the QIAGEN® Genomic DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A paired-end library with a target insert size of 300 bp was prepared using VAHTSTM Universal DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® V3 (Vazyme, ND607, Nanning, China) and sequenced on the Illumina X10 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Illumina sequencing yielded 40.36 Gb (47.6 × coverage) of short reads (Table 1).

For long-read sequencing, high molecular weight genomic DNA was isolated using the QIAGEN® Genomic DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the standard operating procedure provided by the manufacturer. A total of 3-4 μg DNA was used as input material for the ONT library preparation. Long DNA fragments were selected using the PippinHT system (Sage Science, USA). The A-ligation reaction was conducted with the NEBNext Ultra II End Repair/dA-tailing Kit (Ipswich, MA, USA). The SQK-LSK109 adapter (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK) was used for further ligation reaction. A DNA library of 700 ng was constructed and sequenced on a Nanopore PromethION sequencer (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK) at the GrandOmics Biosciences Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China), resulting in a total of 68.3 Gb (53.3 × coverage) clean data (Table 1).

Hi-C library preparation and sequencing

For Hi-C sequencing, the library was prepared according to the standard protocol described by Belton with minor modifications18. The sample was cross-linked with a 2% formaldehyde isolation buffer and then treated with Dpn II to digest nuclei. Biotinylated nucleotides were used to repair tails. The resulting Hi-C library was sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq platform with paired-end 150-bp reads (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at Annoroad Gene Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). A total of 162.1 Gb (137.3 × coverage) of clean data was generated (Table 1).

Transcriptome sequencing

For transcriptome sequencing, total RNA was extracted from each A. rusticus life stage (larva, pupa, and adult) separately using the RNAprep Pure Tissue Kit (Tiangen, China). Libraries were constructed using a TruSeq RNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with the paired-end mode at GrandOmics Biosciences Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China), resulting in a total of 76.3 Gb clean data (Table 1).

Estimation of genomic characteristics

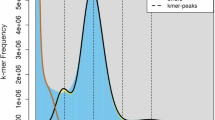

The Illumina raw reads were checked and filtered using Trimmomatic version 0.39-219 to discard reads with adaptors, unknown nucleotides (Ns), or >20% low-quality bases. Genome size, heterozygosity, and duplication were estimated by using Jellyfish version 2.2.1020 and GenomeScope version 2.021 with default parameters. Based on 17-mer depth analysis, the genome size was estimated to be 1004 Mb, 1.32% heterozygosity rate, and 1.06% duplication rate (Table 2, Fig. 1A).

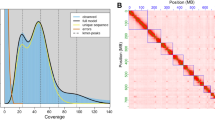

Feature estimation and assembly of Arhopalus rusticus genome. (A) Estimation of A. rusticus genomic features. The 17-mer distributions showed double peaks: the first peak with a coverage of 100 indicates genome duplication, and the highest peak with a coverage of 200 represents a genome-size peak. A. rusticus genome size was calculated to be 1004 Mb with heterozygosity rate of 1.32% and duplication rate of 1.06%. (B) Genome-wide contact matrix of Arhopalus rusticus genome generated using Hi-C data. Each black square represents a pseudo-chromosome. The color bar indicates the interaction intensity of Hi-C contacts.

Genome assembly

We assembled a draft genome at contig level using NextDenovo version 1.2.5 (https://github.com/Nextomics/NextDenovo) with default parameters based on Nanopore long reads. Purge_dups was used to remove alternative haplotype and redundant fragments in the contig assembly. We performed Hi-C analysis to further anchor the assembly into chromosome-scale linkage groups. The Hi-C reads were cleaned using Fastp22 and mapped to the contigs using BWA. YaHS version 1.2a.One23 and Juicertools version 1.19.0224 were used for assembly and manual correction. Finally, two rounds of polishing with ONT reads and Illumina reads were performed using NextPolish version 1.4.025. The resulting chromosome-level genome was 1180.40 Mb with a scaffold N50 of 125.01 Mb, maximum length of 232.23 Mb, and GC rate of 32.32% (Table 2). A total of 98.57% of the genome was anchored to 10 pseudo-chromosomes, which were well-distinguished from each other based on the chromatin interaction heatmap (Fig. 1B).

Genome annotation

Genes in the assembled genome were predicted using a combination of transcriptome-based, ab initio and homology-based methods. For the RNA-based method, short transcriptome reads were mapped to the genome using Hisat226. Then, the aligned BAM files were used to assemble the transcripts using Stringtie version 2.1.427. The genes were predicted using PASA version 2.0.2 with default settings28. The ab initio prediction was performed using AUGUSTUS version 3.4.029 and SNAP version 2006-07-2830, which were trained based on transcripts longer than 300 bp generated by PASA. Homology-based predictions involved downloaded sequences of peptides and transcripts from other species of Coleoptera, including A. glabripennis, Tribolium castaneum31, Dendroctonus ponderosae32 and Diabrotica virgifera33. Redundant genes in the pooled gene set were removed using CD-HIT34. Maker version 3.01.0435 pipeline was used to perform homologue-based prediction. Finally, the evidence from these methods was combined using EvidenceModeler (EVM) version 1.1.136 to generate a high-confidence gene set.

Gene structure and annotations were determined through Eggnog-Mapper version 2.1.937. The methods were used to search against multiple public databases, including Gene Ontology (GO), Clusters of Orthologous Groups of Proteins (COG), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), CAZY, and Pfam. We identified 18,377 protein-coding genes (Table 2) and 11,368 functionally annotated genes, of which most genes (97.47%) were successfully annotated in at least one public database (Table 3).

Repeats prediction and non-coding RNA annotation

Homology-based and de novo prediction methods were used to detect transposable elements (TEs). Repeats sequences were detected using RepeatMasker version 4.1.2 (-no_is -norna -xsmall -q)38, against the Repbase, Dfam database, and species-specific repeat library identified by RepeatModeler version 2.0.3. Finally, 69.87% of the genome was identified to be repeat DNA. Overall, 473,405 retroelements (6,475 short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), 304,805 long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), and 162,125 long terminal repeats (LTR)) and 272,785 DNA transposons were identified. Additionally, 487 satellites and 11,473 simple repeats were identified as tandem repeats (TRs), accounting for 0.05% (Table 4).

Noncoding RNA (ncRNA) annotation was conducted using tRNAscan-SE version 1.3.139, and RNAmmer version 1.240,41 for predicting tRNA and rRNA, respectively. We obtained 4,373 tRNA and 79 rRNA, including 50 8s_rRNA, 16 28s_rRNA, and 13 18s_rRNA in the A. rusticus genome (Table 5).

Identification of ortholog and inference of phylogenetic relationships

To identify single-copy orthologous genes, we utilized the longest protein sequence of each gene from A. rusticus and multiple other species. We reconstructed a species tree with published coleopteran genome data using OrthoFinder version 2.5.542.

Then, protein-coding genes of A. rusticus and another 11 species of Coleoptera were used for phylogenetic analysis with the Drosophila melanogaster43 as an outgroup. These included M. alternatus, M. saltuarius, A. glabripennis, T. castaneum, D. virgifera, D. ponderosae, Leptinotarsa decemlineata44, Agrilus planipennis45, Photinus pyralis46, Onthophagus taurus47 and Protaetia brevitarsis48. All the genome data were downloaded from the NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and GigaDB (http://gigadb.org/dataset/100560). The threshold for all protein sequences ALL-VS-ALL alignment was set to e-5. In the above steps, a total of 50 single-copy homologous groups identified by OrthoFinder were used for phylogenetic tree reconstruction, with D. melanogaster as an outgroup (Table 7). MAFFT was used for multiple sequence comparison of sequences in each group, and FastTree version 2 was used to construct phylogenetic trees.

A molecular clock model is calculated using r8s v1.749. Two nodes with specified diverging time in Timetree database (http://www.timetree.org/) are selected as correction points50 to predict the diverging time of other nodes. This calibration was based on the conclusion that L. decemlineata and D. ponderosae diverged ~191 Mya (million years ago), and T. castaneum and A. planipennis diverged 262 Mya51. The divergence time between A. rusticus and M. alternatus was estimated to be 164.6 Mya (Fig. 2).

Phylogenetic tree and gene ortholog between 13 insect species. The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Arhopalus rusticus and other eleven Coleoptera species, and model species Drosophila melanogaster are used as outgroup, are built using 50 single-copy orthologous genes with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The divergence times are labelled at internodes. The divergence between A. rusticus and Monochamus alternatus diverged 164.6 Mya (Million years ago). The numbers of expanded and contracted gene families are shown in red (expansion) and blue (contraction). The bar chart on the shows the number of orthologous genes of each species.

Gene-family expansion and contraction were estimated using CAFÉ version 4.252 with parameters ‘lambda -s -t’, based on maximum likelihood and reduction methods. Tree topology and branch lengths were considered when inferring the significance of changes to gene-family size in each branch. We identified 77 expanded gene families and 15 contracted gene families in A. rusticus (Fig. 2).

Synteny analysis

We conducted chromosomal collinearity analysis using MCScanX (default parameters) on the A. rusticus genome, with M. saltuarius and M. alternatus as reference genomes. The syntenic blocks among these three cerambycid species were visualized using TBtools. Comparative genomic analysis revealed limited synteny between A. rusticus and M. alternatus, with evidence of significant chromosomal rearrangements including fragmentation and fusion events. Specifically, chromosomes 4 and 9 of A. rusticus were derived from fission of chromosome 4 in M. alternatus (Fig. 3).

Data Records

The genome project was deposited in NCBI under BioProject No. PRJNA953210. Illumina sequencing data for genome survey were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession number SRR2615123753. Nanopore sequencing data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession number SRR2615825954. Hi-C sequencing data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession number SRR2627134755. RNA-seq data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession numbers SRR26151756-SRR2615175856,57,58. The final chromosome assembly was deposited in GenBank at NCBI under accession number JBIRAU00000000059. The contaminant file, single-copy orthologous genes, gene-family expansion and contraction, gene function annotation, and repeat annotation are available in Figshare60.

Technical Validation

The Hi-C heatmap exhibits the accuracy of genome assembly, with relatively independent Hi-C signals observed between 10 pseudo-chromosomes (Fig. 1B). Moreover, we assessed the accuracy of the final genome assembly by mapping Illumina short reads to the A. rusticus genome with BWA-MEM2 version 0.7.172161. The analysis showed that 96.7% of short reads were successfully mapped to the assembled A. rusticus genome.

Furthermore, we evaluated the completeness of the final genome assembly using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologues (BUSCO version 5.2.2) using the insecta_odb10 database, which contains 1367 conserved genes62. The analysis revealed completeness of 93.6% for the A. rusticus genome with only 1.6% of BUSCO genes being fragmented, 4.8% being missing, and 0.9% being duplicated (Table 6).

Code availability

There were no custom scripts or code utilized in this study.

References

Žunič-Kosi, A., Stritih-Peljhan, N., Zou, Y., McElfresh, J. S. & Millar, J. G. A male-produced aggregation-sex pheromone of the beetle Arhopalus rusticus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae, Spondylinae) may be useful in managing this invasive species. Scientific Reports 9, 19570, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56094-7 (2019).

Bense, U. Longhorn beetles: illustrated key to the Cerambycidae an Vesperidae of Europe. (Margraf Publishers GmbH, 1995).

Fan, Y., Zhang, X., Zhou, Y. & Zong, S. Prediction of the global distribution of Arhopalus rusticus under future climate change scenarios of the CMIP6. Forests 15, 955, https://doi.org/10.3390/f15060955 (2024).

Kadyrov, A. K., Karpiński, L., Szczepański, W. T., Taszakowski, A. & Walczak, M. New data on distribution, biology, and ecology of longhorn beetles from the area of west Tajikistan (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae). ZooKeys 606 (2016).

Wang, Q. & Leschen, R. A. B. Identification and distribution of Arhopalus species (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae: Aseminae) in Australia and New Zealand. New Zealand Entomologist 26 (2003).

Gutirrez, N. & Noguera, F. A. New distributional records of Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) from Mexico. Pan-pacific Entomologist 91, 135–147, https://doi.org/10.3956/2015-91.2.135 (2015).

Whitehouse, N. J. Forest fires and insects palaeoentomological research from a subfossil burnt forest. Palaeogeography 164, 231–246 (2000).

Lindhe, A. & Lindelöw, Å. Cut high stumps of spruce, birch, aspen and oak as breeding substrates for saproxylic beetles. Forest Ecology and Management 203, 1–20 (2004).

Campbell, J. W., Hanula, J. L. & Outcalt, K. W. Effects of prescribed fire and other plant community restoration treatments on tree mortality, bark beetles, and other saproxylic Coleoptera of longleaf pine, Pinus palustris Mill., on the Coastal Plain of Alabama. Forest Ecology and Management 254, 134–144 (2008).

Bradburyl, P. M. The effects of the burnt pine longhorn beetle and wood-staining fungi on fire damaged pinus radiata in Canterbury. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 43 (1998).

Kaufmann & U., R. R. Notes on the distribution of the British Longicorn Coleoptera. Entomology Monthly Management, 66-85 (1948).

Epanchin-Niell, R. S. & Rebecca, S. Economics of invasive species policy and management. Biological Invasions 19, 1–22 (2017).

Sama, G. Notte sulla nomenclatura dei Cerambycidae della regione Meditarrenea (Coleoptera). Bolletino della Societa Entomologica Italiana (Genova) 123, 232–128 (1991).

Richards, S. et al. The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum. Nature 452, 949–955 (2008).

McKenna, D. D. et al. Genome of the Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis), a globally significant invasive species, reveals key functional and evolutionary innovations at the beetle-plant interface. Genome Biology 17, 227 (2016).

Gao, Y. F. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the Japanese sawyer beetle Monochamus alternatus. Scientific Data 11, 199, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03048-y (2024).

Fu, N. N. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Monochamus saltuarius reveals its adaptation and interaction mechanism with pine wood nematode. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 222, 325–336 (2022).

Belton, J. M. et al. Hi-C: a comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods 58, 268–276 (2012).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Marcais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nature Communications 11, 1432 (2020).

Chen, S. F., Zhou, Y. Q., Chen, Y. R. & Gu, J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Zhou, C. X., McCarthy, S. A. & Durbin, R. YaHS: yet another Hi-C scaffolding tool. Bioinformatics 39, btac808 (2023).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell System 3, 95–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002 (2016).

Hu, J., Fan, J. P., Sun, Z. Y. & Liu, S. L. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics 36, 2253–2255 (2020).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nature Biotechnology 37, 907–915 (2019).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nature Biotechnology 33, 290–295 (2015).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome biology 9, 1–22 (2008).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Research 34, W435–W439 (2006).

Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-1185-1159 (2004).

Tribolium Genome Sequencing, C. et al. The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum. Nature 452, 949–955 (2008).

Keeling, C. I. et al. Draft genome of the mountain pine beetle, Dendroctonus ponderosae Hopkins, a major forest pest. Genome Biology 14, R27 (2013).

Lata, D., Coates, B. S., Walden, K. K. O., Robertson, H. M. & Miller, N. J. Genome size evolution in the beetle genus Diabrotica. G3-Genes Genomes Genetics 12, jkac052 (2022).

Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150–3152 (2012).

Cantarel, B. L. et al. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Research 18, 188–196 (2008).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biology 9, R7 (2008).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through orthology assignment by eggNOG-mapper. Molecular Biology and Evolution 34, 2115–2122 (2017).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. S. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 5, 4.10.11–14.10.14 (2009).

Schattner, P., Brooks, A. N. & Lowe, T. M. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 33, W686–689 (2005).

Lagesen, K. et al. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Research 35, 3100–3108 (2007).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Research 25, 955–964 (1997).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biology 16, 157, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2 (2015).

Adams, M. D. et al. The Genome Sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Scinence 287, 2185–2195 (2000).

Pelissie, B. et al. Genome Resequencing Reveals Rapid, Repeated Evolution in the Colorado Potato Beetle. Molecular Biology And Evolution 39, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msac016 (2022).

Lord, N. P. et al. A cure for the blues: opsin duplication and subfunctionalization for short-wavelength sensitivity in jewel beetles (Coleoptera: Buprestidae). BMC Evolutionary Biology 16, 107, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-016-0674-4 (2016).

Fallon, T. R. et al. Firefly genomes illuminate parallel origins of bioluminescence in beetles. Elife 7, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495 (2018).

Zattara, E. et al. Onthophagus taurus Genome Assembly 1.0, https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/onthophagus-taurus-genome-assembly-10 (2016).

Wang, K. et al. De novo genome assembly of the white-spotted flower chafer (Protaetia brevitarsis). Gigascience 8, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giz019 (2019).

Sanderson, M. J. r8s: inferring absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times in the absence of a molecular clock. Bioinformatics 19, 301–302 (2003).

Hedges, S. B., Dudley, J. & Kumar, S. TimeTree: a public knowledge-base of divergence times among organisms. Bioinformatics 22, 2971–2972, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btl505 (2006).

Zhang, S. Q. et al. Evolutionary history of Coleoptera revealed by extensive sampling of genes and species. Nature Communications 9, 205, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02644-4 (2018).

Han, M. V., Thomas, G. W., Lugo-Martinez, J. & Hahn, M. W. Estimating gene gain and loss rates in the presence of error in genome assembly and annotation using CAFE 3. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30, 1987–1997, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst100 (2013).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26151237 (2023).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26158259 (2023).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26271347 (2023).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26151756 (2023).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26151757 (2023).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26151758 (2023).

Gao, Y. & Wei, S. Arhopalus rusticus isolate YG-2024a, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBIRAU000000000.1 (2025).

Gao, Y. F., Wei, S. J. & Zong, S. X. Genome assembly and annotation of the longhorn beetle Arhopalus rusticus. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26941057 (2024).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simão, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38, 4647–4654 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Major Innovation Engineering Program of Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Plan (2024CXGC010911), and the Program of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (JKZX202208).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.X.Z. and S.J.W. designed the study. J.X.W. contribute to the samples; Y.F.G., F.Y.Y. and W.S. contribute to the genome assembly and annotation. Y.F.G. and S.J.W. wrote and revised the manuscript. The final manuscript has been read and approved by all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, YF., Yang, F., Chen, JC. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the longhorn beetle Arhopalus rusticus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). Sci Data 12, 1171 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05523-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05523-6