Abstract

Accurate identification and localization of cephalometric landmarks are crucial for diagnosing and quantifying anatomical abnormalities in orthodontics. Traditional manual annotation of these landmarks on lateral cephalograms (LCRs) is time-consuming and subject to inter- and intra-expert variability. Attempts to develop automated landmark detection systems have persistently been made; however, they are inadequate for orthodontic applications due to the unavailability of a diverse dataset. In this work, we introduce a state-of-the-art cephalometric dataset designed to advance AI-driven quantitative morphometric analysis. Our dataset comprises 1,000 LCRs acquired from seven different imaging devices with varying resolutions, making it the most diverse and comprehensive collection to date. Each radiograph is meticulously annotated by clinical experts with 29 cephalometric landmarks, including the most extensive set of dental and soft tissue markers ever included in a public dataset. Additionally, we provide cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) stage annotations, marking the first standard resource for CVM classification. We anticipate that this dataset will serve as a benchmark for developing robust, automated landmark detection frameworks, with applications extending beyond orthodontics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Quantitative morphometry of human skull and cephalometric analyses of spatial relationships among teeth, jaws, and cranium are considered to be the cornerstones of contemporary orthodontics, orthognathic treatment, and other areas of oral and maxillofacial surgeries1. Such analyses are usually carried out using two-dimensional (2D) radiographic images often referred to as cephalograms. In 1982, Thomas Rakosi defined 90 anatomically relevant anchor points, i.e., landmarks, of which 29 have been widely used by orthodontists on a routine basis2. A conventional cephalometric analysis involves the identification of anatomical landmarks, measurement of various angles and distances between these identified landmarks, and qualitative assessment of anatomical abnormalities from these angles and distances3. It assists clinicians in diagnosing the craniofacial condition of a patient by providing clinical interpretation of bony structures of the skull and surrounding soft tissues. In clinical practice, orthodontists usually map out contours of craniofacial structures on X-ray images manually and then identify anatomical landmarks from various geometrical features. However, the process of manual annotation is tedious, time-consuming and subjective4. Although cephalometric tracing is generally performed by trained orthodontists, several reports have raised concerns regarding significant inter- and intra-observer variabilities among them5 due to their diverse training and experience backgrounds. Since identifying anatomical abnormalities of hard and soft tissues and subsequent treatment procedures are highly sensitive to precise estimation of landmark locations, a poor manual cephalometric analysis might have severe repercussions

With advances in machine learning and computer vision over the past few years, it has become increasingly clear that automatic detection of cephalometric landmarks could be a promising solution for improving inter-rater and intra-rater reliability, reducing tracing time, and enhancing orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. Recognizing the significance of automatic landmark detection, IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) hosted the challenge of Automatic Cephalometric Landmark Detection for Diagnosis in Cephalometric X-ray Images in both 20146 and 20157. Wang et al.8 introduced the first cephalometric landmark detection dataset, comprising of 400 high-resolution X-ray images of patients ranging in age from six to 60 years. All images were obtained using the Soredex CRANEX Excel cephalometric X-ray machine with spatial dimensions of 1935 × 2400 pixels, at a resolution of 0.1 mm/pixel in both directions. However, there are several concerns regarding the generalizability and reliability of ground truth annotations. For instance, the training dataset only includes 150 cephalograms randomly selected from 400 patients with a wide range of ages. Furthermore, all cephalograms are obtained from a single X-ray imaging device. With this limited amount of training data, an AI algorithm may struggle to generalize on such a diverse set of patients and be prone to overfit9. Additionally, the mean intra-observer variability of the senior and junior orthodontists is 1.73 ± 1.35 mm and 0.90 ± 0.89 mm, respectively, while the mean inter-observer variability between the two orthodontists is 1.38 ± 1.55 mm which produced a mean radial error (MRE) of 2.02 ± 1.53 mm on test data. This degree of variability is extremely large, considering the clinical precision range of 2 mm. Consequently, there is a high probability that the trained model may contain unnecessary bias, suggesting that there is a limit to clinical applications merely with this dataset10. Despite these limitations, this dataset has served as a benchmark for the comparison of various cephalometric landmark detection models and laid the foundation of a new era in the field of dental X-ray imaging.

In 2020, Zeng et al.11 published the PKU cephalogram dataset, which consisted of 102 cephalograms from patients of ages 9 to 53 years. These images were captured using the Planmeca ProMax 3D cephalometric X-ray machine, with average spatial dimensions of 2089 × 1937 pixels and a resolution of approximately 0.125 mm/pixel. While this dataset was not particularly comprehensive, featuring only 102 cephalograms with the same 19 landmarks, it was still a valuable addition to the field of automated cephalometric landmark detection. Several other datasets containing large numbers of cephalograms annotated with an extensive amount of anatomical landmarks have also been offered and used on occasion. For example, Qian et al.12 proposed a multi-head attention neural network, CephaNN, for cephalometric landmark detection and used a private collection of 400 cephalograms with varying features and properties from various devices. Kunz et al.13 created a dataset with 1792 cephalometric X-ray images acquired from Sirona Orthophos XG radiographic machine. On each image, twelve examiners identified and marked a total of 18 radiographic landmarks. This dataset was the largest dataset ever annotated following excellent marking protocols, but unfortunately, it was not made available, and the research community was once again deprived of a sophisticated dataset. In the field of orthodontics, the soft tissue paradigm14 has led to the consideration of facial soft tissue in all types of jaw and tooth movements. As a result, cephalometric studies include various soft tissue parameters, such as facial convexity, nasolabial angle, the position of upper and lower lips, mentolabial sulcus, position of soft tissue chin and lower anterior face height15 etc. However, the publicly available datasets only include four soft tissue landmarks, which are insufficient for most soft tissue cephalometric analyses. Additionally, these datasets do not include important occlusal landmarks, which are essential for constructing the occlusal plane, an important factor in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning that can change during treatment.

In addition to selecting the most appropriate treatment approach and biomechanics, the timing of treatment delivery is also crucial for orthodontic treatment effectiveness. Accurate assessment of facial growth and quantification of skeletal maturation stage, particularly mandibular growth, plays a vital role in orthodontic diagnosis, prognosis, treatment planning and outcomes. Several biological indicators, such as dental development and eruption times16, chronological and dental age17, ossification of hand and wrist bones18, and cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) and morphology19, have been proposed to assess skeletal maturity. Among these, the CVM stage method is the most commonly used by orthodontists since it can be assessed using traditional lateral cephalograms and avoids additional radiographic exposure of a second radiograph. Despite the widespread use of the CVM stages method in assessing skeletal maturation and growth spurts, the process can be challenging and time-consuming for practitioners, leading to sub-optimal intra-observer agreement20. Several researchers21,22,23,24,25,26 have explored the promising applications of artificial intelligence (AI) to automate the process of CVM assessment. For instance, Rahimi et al.26 implemented two transfer learning models based on ResNet-101, which were independently fine-tuned to determine CVM stage and pubertal growth spurt using lateral cephalograms. Another study by Seo et al.24 aimed to evaluate and compare the performance of six advanced deep learning models based on CNNs for CVM classification in lateral cephalograms. Despite these extensive studies, it is surprising that there remains a lack of a standard dataset for CVM stage estimation.

Considering all these limitations, we propose a new benchmark dataset27 consisting of 1000 cephalometric X-ray images acquired from 7 different X-ray imaging devices with varied resolutions. The dataset includes annotations for two different cephalometric analyses: anatomical landmark detection and CVM stage classification. A team of 6 clinicians, including 2 expert orthodontists, were responsible for the annotation process, which was carried out in two phases. In the first phase, referred to as the labelling phase, two junior orthodontists independently annotated all of the cephalograms with 29 most commonly used anatomical landmarks. In the second phase, referred to as the reviewing phase, two senior orthodontists collaboratively reviewed and corrected the annotations. For CVM stage classification, our senior orthodontists assigned each image to one of the six possible stages, and the images for which they disagreed, were referred to expert orthodontists. The salient features of our dataset are summarized as follows:

-

Our dataset boasts a diverse and extensive collection of 1000 cephalograms acquired from 7 different X-ray imaging devices with varying resolutions, making it the most comprehensive cephalometric dataset to date.

-

The dataset features 29 most commonly used anatomical landmarks, with 15 skeletal, 8 dental, and 6 soft-tissue landmarks, annotated by a team of 6 skilled orthodontists in two phases, following extensive labelling and reviewing protocols.

-

By annotating the CVM stages of each cephalogram in our dataset, we have also created the first standard resource for automatic CVM classification.

We named our dataset ’Aariz, which is an Arabic word meaning cheek. Since a cephalogram is an X-ray scan of the craniofacial area (i.e. cheek), we have taken ’Aariz in these terms. A thorough comparison of our dataset against other available and non-available datasets is presented in Table 1, highlighting the unique features and superior characteristics of our dataset. We believe that this dataset will not only derive forward research and innovation in automatic cephalometric landmark identification and CVM stage classification, but will also mark the beginning of a new era in the discipline.

Methods

The scarcity of high-quality cephalometric datasets for research purposes is primarily because of the difficulty in obtaining access to medical images due to patients’ privacy concerns. Even if one is successful in obtaining access to these images, the process of annotating them can be a costly and time-consuming endeavour. However, the significance of such datasets cannot be understated, as they provide valuable resources for researchers seeking to enhance automated AI systems used in cephalometric analysis. In an effort to address these problems, we embarked on a research collaboration with Riphah International University in 2020. The main objective of this research was to create a benchmark dataset that not only addresses the limitations of existing datasets but also helps improve the performance of cephalometric landmark tracing algorithms. An ethical approval was received from the Institutional Review Committee of Islamic International Dental College, Riphah International University, Islamabad, Pakistan (IRB Number IIDC/IRC/2020/001/012). This approval includes consent for the open publication of the anonymized dataset under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license, ensuring compliance with patient privacy and ethical standards.

Dataset Description

We have proposed a new benchmark dataset consisting of 1000 cephalometric X-ray images, which were collected from 1000 patients ranging in age from 12 to 62 years, and acquired from 7 different X-ray imaging devices with varying resolutions. Table 2 summarizes all of the X-ray imaging devices used to obtain the cephalograms, as well as their respective resolutions and the number of cephalograms from each machine. Each cephalogram is labelled with 29 cephalometric landmarks, which are most commonly used in clinical settings and can be employed for a variety of cephalometric measurements. These landmarks are selected from 3 fundamental categories of anatomical structures: skeletal, dental and soft-tissue. The skeletal structure contributes 15 landmarks, whereas 8 landmarks are related to dental structures, and 6 landmarks are related to soft-tissue structures, making it the most comprehensive dataset with the highest number of soft-tissue landmarks in any publicly available data resource to date. In Table 4, we have compiled a list of the cephalometric landmarks that are included in our dataset, organized by their respective categories, and accompanied by their clinical definitions to provide a clear understanding of their role in cephalometric analysis.

To ensure the accuracy and consistency of dataset annotations, we enlisted the help of a team of skilled clinicians from the Islamic International Dental College in Islamabad, Pakistan. Comprised of 2 expert orthodontists with a combined clinical experience of 25 years, as well as 4 additional orthodontic professionals, this team was responsible for deliberately annotating each of the 1000 cephalograms in the dataset. The expert orthodontists also presided over the entire annotation process, occasionally participating in the labelling themselves to ensure the highest level of quality and consistency. The overall dataset is divided into three subsets: training, validation and testing, with 700, 150, and 150 cephalometric X-ray radiographs, respectively. The images from each of the X-ray machines have different spatial dimensions and are uniformly distributed in each subset. This ensures that our dataset is well-rounded and representative of the diverse range of images collected from various X-ray machines.

Data Acquisition

The dataset consists of lateral cephalometric X-ray images collected from the archives of patients undergoing orthodontic treatment at Islamic International Dental College, Riphah International University, Islamabad, Pakistan. We obtained written consent from all patients for the use of their radiographic records for educational and research purposes. For participants under 18 years of age, written informed consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians. The confidentiality of all patient records was strictly maintained by obscuring any identifying information. Table 3 features the inclusion and exclusion criteria that we followed during data collection.

Among 3500 cephalometric radiographs, our junior orthodontists curated 1000 radiographs that fulfil the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We matched the radiographs with their corresponding imaging machines and assigned them anonymous identifiers to protect patient privacy. The final dataset was then expertly reviewed and approved by senior orthodontists, marking the beginning of the labelling phase.

Dataset Annotation Process

Before diving into the annotation process, our team of expert orthodontists conducted a rigorous training session, during which they emphasized the importance of adhering to standard cephalometric terminology and highlighted the most commonly confused landmarks. All the clinicians were required to annotate a set of preliminary test images, which were then reviewed by expert orthodontists. Any annotations that did not meet the required standards were corrected and the clinicians received additional feedback and guidance. This process was repeated until all clinicians achieved the desired proficiency level in confidently distinguishing between commonly confused anatomical structures. With such a solid foundation in proper cephalometric annotation techniques and protocols, our team of clinicians was ready to embark on the meticulous task of annotating the real dataset, which culminated in a series of reviews and corrections to ensure the highest level of accuracy.

Cephalometric Landmarks

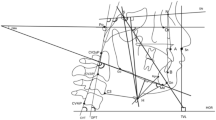

The annotation process of cephalometric landmarks was carried out in two phases. In the first phase, two junior orthodontists independently marked all of the cephalograms, and in the second phase, two senior orthodontists collaboratively reviewed and corrected the markings as needed. The average of the markings by junior orthodontists and the average of the markings by senior orthodontists are provided separately. The mean of these two averaged markings will be used as the ground truth for cephalometric landmarks. The team utilized LabelBox1 as a labelling tool to annotate the cephalograms. At the end of the annotation process, inter-observer variability between junior and senior orthodontists was found to be 0.494 ± 1.097 mm in terms of mean radial error ± standard deviation. Figure 1 features the landmark-wise distribution of inter-observer variabilities between the two groups of clinicians.Footnote 1

Labelling Phase

The first phase of cephalometric landmark annotations, i.e. labelling phase, was accomplished in three rounds. Figure 2(a) illustrates the state of inter-observer variability with respect to each landmark during all these rounds. To begin with labelling, two junior orthodontists with five years of clinical experience, referred to as labellers, independently traced each cephalogram with 29 anatomical landmarks. This first round of labelling was statistically reviewed and the inter-observer variability was determined to be 0.425 ± 1.170 mm in terms of mean radial error (MRE) ± standard deviation (SD). However, as shown in Fig. 2(a) (top), it was observed that the inter-observer variability between the labellers in terms of mean radial error was quite high for some landmarks (e.g. Ramus, Gonion and Porion etc). Therefore, to further improve markings, a total of 601 cephalograms were identified for which the mean radial error of critical landmarks was found to be greater than a threshold (i.e. 50 pixels or approximately 5 mm). The erroneous landmarks were re-traced by labellers under the supervision of expert orthodontists. As a result, mean inter-observer variability was significantly reduced to 0.341 ± 0.964 mm. Finally, we focused on reducing the standard deviation between landmark annotations. Based on statistical analysis, it was revealed that the standard deviation for the lower incisor tip was significantly large throughout the labelling phase, leading to the identification of 12 cephalograms with incorrect markings for this landmark. These were subsequently corrected by expert orthodontists, resulting in a significant reduction in standard deviation for that landmark. Through this multi-stage labelling process, we aimed to reduce inter-observer variability and ensure the accuracy and reliability of the labelling phase.

A visual representation of inter-observer variability in landmark annotations. The graphs showcase the precision of our annotation process across all rounds of the labelling and reviewing phases. (left) The top, middle, and bottom rows show the variability among junior orthodontists during the three rounds of the labelling phase. (right) The top, middle, and bottom rows depict the variability among senior orthodontists during all the rounds of the reviewing phase.

To calculate the intra-observer variabilities between the orthodontists, we randomly selected 100 cephalometric images from the dataset, one image from every 10 images, as a representative sample. We then asked the labellers to re-annotate the images in this subset, assuming that it reflects the characteristics of the entire dataset. As a result, the intra-observer variability was estimated by comparing these new annotations to their corresponding previous ones. Table 5 presents the mean intra- and inter-observer variabilities of both labellers at the end of the labelling phase.

Reviewing Phase

The second phase of cephalometric landmark annotations, i.e. reviewing phase, was also carried out in three rounds. In this phase, two senior orthodontists with clinical expertise ranging from 7 to 10 years, referred to as reviewers, reviewed the annotations by labellers at the end of the labelling phase and corrected them as needed. Figure 2(b) illustrates the trend of inter-observer variability with respect to each landmark during all these rounds. As described in the previous section, both labellers had annotated each cephalogram separately, therefore, each reviewer was required to review a total of 2000 labelled cephalograms, which was a daunting task. Therefore, the reviewers worked together, with one reviewing the markings of labeller 1 for the first 500 cephalograms and the markings of the other labeller for the remaining 500 cephalograms, while the other reviewer did the opposite. Through this collaborative approach, the reviewers were able to effectively review all of the cephalograms and made necessary corrections. The reviewing phase followed a similar pattern as the labelling phase, starting with a general review of the entire dataset, followed by the rounds focusing on reducing radial error and targeting the reduction of standard deviation. To measure the intra-observer variability of reviewers, we used the same subset of 100 cephalograms that had already been annotated by the labellers. The reviewers then collaboratively reviewed and assessed these annotations, allowing us to calculate the intra-observer variability. Table 6 presents the mean intra- and inter-observer variabilities of both reviewers at the end of the reviewing phase.

Together, the rigorous labelling and reviewing processes ensured the accuracy and consistency of annotations in our dataset. As shown in Fig. 3(a), a typical cephalogram annotated with all 29 landmarks exemplifies the anatomical precision achieved, while (b) highlights the resulting cephalometric tracing used for downstream analysis.

CVM Stages

During the labelling process, our clinicians apprised the fact that there is no standard dataset available for automatic CVM stage classification. With this in mind, we decided to not only annotate cephalometric landmarks but also include CVM stage labels for each cephalogram in our dataset. However, identifying the CVM stage is a challenging task; in certain circumstances, even senior orthodontists have to put in considerable effort. Therefore, to ensure that the labellers were equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to accurately identify CVM stages, the expert orthodontists conducted a comprehensive training session, primarily focused on the importance of following the standard CVM degree method in determining CVM stages. Unfortunately, after the completion of the labelling phase, we found that the CVM agreement between the two labellers was only 36.3%.

Given the difficulties experienced by the junior orthodontists in identifying CVM stages, even with proper training, we decided to have the senior orthodontists take on the task of CVM stage labelling. Through their collaborative efforts, the agreement between the reviewers improved significantly to 96.6%. of the 1000 cephalograms, the reviewers assigned the same label to 906 images, while differing in their assessment of the remaining 94. These 94 cephalograms were reviewed by expert orthodontists, and their markings were considered the final labels. A visual representation of the distribution of CVM stages in our dataset can be seen in Fig. 4.

Data Records

The Aariz dataset27 has been deposited in the Figshare repository at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27986417.v1and is organized into three primary subsets: train, validation, and test. Each subset contains lateral cephalometric radiographs (LCRs) along with corresponding annotations. The Annotations directory contains structured .json files divided into two main categories: Cephalometric Landmarks and Cervical Vertebral Maturation (CVM) Stages. Landmarks annotations are further categorized into two sub-folders - Junior Orthodontists and Senior Orthodontists - to provide multi-expert perspective. Since two orthodontists individually labeled the data, we have provided the average annotations of both in the Junior Orthodontists folder. Similarly, since the data was collectively reviewed by two orthodontists, their average annotations have been provided in the Senior Orthodontists folder. Finally, the average of both the junior and senior annotations for a specific patient is considered as ground truth. A visual overview of the dataset’s folder hierarchy and organization is provided in Fig. 5.

In addition to radiographs and annotations, the dataset includes a supplementary .csv file, which provides metadata on the imaging devices used for cephalogram acquisition. This file contains the information corresponds to the spatial calibration of each X-ray machine and is essential for clinical evaluation of automated landmark detection models. Since landmark detection accuracy is typically assessed in millimeters, this pixel-to-mm resolution allows researchers to convert model prediction errors (e.g., Mean Radial Error or MRE) from pixel space into real-world units. Consequently, users of the dataset can evaluate AI-based models against clinically meaningful thresholds, such as 2.0 mm, 2.5 mm, 3.0 mm, and 4.0 mm, which are commonly adopted in cephalometric landmark detection literature to reflect various error margins. This added metadata enhances the dataset’s reliability and distinguishes it from many existing public cephalometric datasets by enabling precise, clinically grounded benchmarking across diverse imaging conditions.

Technical Validation

The creation of our cephalometric dataset involved a rigorous two-phase annotation process designed to minimize inter-observer variability and ensure the highest possible accuracy of landmark identification. As detailed in Section, this process was conducted across multiple rounds involving both junior and senior orthodontists. In the first phase, two junior orthodontists independently annotated 1000 cephalograms with 29 anatomical landmarks. This labelling phase underwent three critical review rounds, progressively reducing the mean radial error from 0.425 ± 1.170 mm to 0.341 ± 0.964 mm. The team systematically addressed variabilities in landmark annotations, paying special attention to critical landmarks and those with significant standard deviations. The subsequent reviewing phase involved two senior orthodontists, who collaboratively reviewed the initial annotations. They employed a strategic approach, dividing the 2000 labelled cephalograms between them to ensure a comprehensive review while managing the substantial workload.

Despite the statistical rigor of our annotation process, the complexity of cephalometric landmark identification presented unique challenges that could not be entirely captured by quantitative analysis alone. In one critical instance, we observed a significant radial error between the markings when one of the labellers had accidentally swapped two landmarks due to similar anatomical structures. Since the other labeller had correctly marked these landmarks, the statistical analysis flagged this error and it was corrected. However, such errors could have gone undetected if both labellers had made the same mistake. This was an alarming situation because the presence of such errors is a regular occurrence owing to human involvement, and we had already faced such a situation.

Consequently, we implemented an additional layer of validation, mandating that our expert orthodontists conduct a comprehensive review of the entire dataset. Their primary objective was to verify that no landmarks had been inappropriately interchanged. Our diligence paid off, as this thorough expert review uncovered 8 instances where both the labellers had accidentally swapped the locations of two landmarks. Illustrative examples of these landmark swaps are presented in Fig. 6, demonstrating the importance of comprehensive, expert-level review in maintaining dataset integrity.

A visualization of the perils of mislabelling caused by swapped landmarks, exemplifying how two labellers accidentally swapped the locations of two landmarks, even though they were correctly marked in their respective positions. (a) shows the case where gonion (Go) was swapped with gnathion (Gn) (b) illustrates labrale inferius (Li) being switched with labrale superius (Ls) (c) presents posterior nasal spine (PNS) being swapped with pronasale (Pn).

The development of automated landmark detection systems has been hindered by a lack of reliable datasets. In an effort to address this gap, we present a novel dataset of lateral cephalometric radiographs (LCRs) annotated with 29 of the most commonly used anatomical landmarks, including 15 skeletal, 8 dental, and 6 soft-tissue landmarks. Our dataset, which comprises 1000 radiographs obtained from 7 different imaging devices with varying resolutions, is the most diverse and comprehensive cephalometric dataset to date. In addition to the extensive annotation of landmarks, our team of clinical experts also labelled the cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) stage of each radiograph, creating the first standard resource for CVM classification. A representative sample of annotated cephalograms from each imaging device, along with their respective CVM stages, is illustrated in Fig. 7. Offering a diverse range of images acquired from different X-ray machines and providing a comprehensive set of annotations, our dataset has the potential to greatly improve the accuracy and reliability of automated cephalometric landmark detection systems, ultimately leading to more informed orthodontic treatment decisions.

Evaluation of Baseline Model

To validate the clinical relevance and research utility of the our dataset, we introduced it to the international research community by organizing the CEPHA29: Automatic Cephalometric Landmark Detection Challenge28 in conjunction with the IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) in 2023. The diverse nature of the dataset quickly garnered attention, highlighting the community’s growing interest in robust, real-world AI solutions for orthodontic imaging. The enthusiastic participation of 29 international teams from across the globe stands as a strong testament to the success and applicability of the dataset. To further facilitate researchers and benchmark performance, we developed a baseline model29, specifically, a novel two-stage cascaded convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture. In the first stage, a CNN is employed to localize and extract the craniofacial region from the cephalometric image. This step ensures uniformity in feature representation across varying imaging conditions, thereby reducing potential biases caused by differences in acquisition protocols or resolutions. In the second stage, the extracted region is passed to another CNN, which performs heatmap regression to predict the precise locations of the anatomical landmarks.

The proposed model was evaluated on the test set of the Aariz dataset and achieved a mean radial error (MRE) of 1.789 ± 6.548 mm, well within the clinically accepted threshold of 2 mm. Furthermore, the model demonstrated success detection rates (SDRs) of 78.44% within 2 mm and 94.44% within 4 mm, underscoring its reliability for practical applications. To gain deeper insights into the design and robustness of our framework, we also conducted extensive ablation studies, analyzing the impact of key components and pre-processing strategies. The results affirm the effectiveness of our approach and highlight the strength of leveraging a multi-resolution, real-world dataset to support automated cephalometric analysis. Overall, this baseline model-alongside the Aariz dataset-lays a strong foundation for further research and development in AI-powered orthodontic diagnostics and treatment planning.

Clinical Relevance and Future Directions

The Aariz dataset has been carefully curated to support clinically meaningful training and evaluation of AI models for cephalometric landmark detection. It was intentionally designed to capture diversity in imaging sources by including radiographs from seven different devices with varying resolutions. Its utility has been further demonstrated through a baseline two-stage CNN model, which achieved a mean radial error (MRE) within the clinically accepted threshold of 2 mm-highlighting its potential to enable accurate and consistent landmark detection across varied imaging conditions. However, despite these strengths, the dataset is currently positioned as a robust foundation for developing and benchmarking AI models, serving as a research-enabling resource rather than a ready-to-use clinical solution.

To build on this foundation and extend its real-world applicability, we are actively planning an expansion of the Aariz dataset. This includes incorporating radiographs from patients with orthodontic appliances (e.g., braces) and missing teeth-conditions that are clinically common but often underrepresented in existing datasets. Additionally, we aim to broaden the dataset’s geographic and ethnic diversity by sourcing data from multiple regions, thereby enhancing its generalizability across a wider range of clinical scenarios. Through this continuous evolution, the Aariz dataset aspires to serve not only as a high-quality benchmark for AI research but also as a stepping stone toward the development of clinically viable, globally relevant solutions in automated cephalometric analysis.

Usage Notes

The dataset has been fully anonymized and is publicly available under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license via Figshare. All personally identifiable information has been removed in compliance with ethical guidelines, and institutional approval for public data sharing has been obtained (IRB Number: IIDC/IRC/2020/001/012). Although openly accessible, users must refrain from any attempts at re-identification of individuals, in accordance with ethical standards for handling human data.

Code availability

To facilitate the use of our dataset and to provide a starting point for researchers, we have made the source code for the data processing, transformations, and evaluation available on our GitHub repository: https://github.com/manwaarkhd/cephalometrix. The repository includes scripts for reading the cephalograms and corresponding annotations from their respective folders. We encourage researchers to use and modify our code as needed to adapt to their research questions and needs, and to provide feedback and suggestions for improvements.

Notes

References

Proffit, W. R., Fields, H. W. Jr. & Sarver, D. M. Contemporary orthodontics. (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2006).

Rakosi, T. An Atlas and Manual of Cephalometric Radiography. (Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, 1982).

Arik, SercanÖ., Ibragimov, B. & Xing, L. Fully automated quantitative cephalometry using convolutional neural networks. Journal of Medical Imaging 4(1), 014501 (2017).

Kamoen, A., Dermaut, L. & Verbeeck, R. The clinical significance of error measurement in the interpretation of treatment results. The European Journal of Orthodontics 23(5), 569–578 (2001).

Durão, A. P. R. et al. Cephalometric landmark variability among orthodontists and dentomaxillofacial radiologists: a comparative study. Imaging Science in Dentistry 45(4), 213–220 (2015).

Wang, C. W., Huang, C. T., Li, C. H. & Chang, S. W. A grand challenge for automated detection of critical landmarks for cephalometric x-ray image analysis. In IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (2014).

Wang, C.-W. et al. Evaluation and comparison of anatomical landmark detection methods for cephalometric x-ray images: A grand challenge. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 34(9), 1890–1900 (2015).

Wang, C.-W. et al. A benchmark for comparison of dental radiography analysis algorithms. Medical Image Analysis 31, 63–76 (2016).

Domingos, P. A few useful things to know about machine learning. Communications of the ACM 55(10), 78–87 (2012).

Khalid, M. A., Khurshid, A., Zulfiqar, K., Bashir, U. & Fraz, M. M. A two-stage regression framework for automated cephalometric landmark detection incorporating semantically fused anatomical features and multi-head refinement loss. Expert Systems with Applications 255, 124840 (2024).

Zeng, M., Yan, Z., Liu, S., Zhou, Y. & Qiu, L. Cascaded convolutional networks for automatic cephalometric landmark detection. Medical Image Analysis 68, 101904 (2021).

Qian, J. et al. Cephann: a multi-head attention network for cephalometric landmark detection. IEEE Access 8, 112633–112641 (2020).

Kunz, F., Stellzig-Eisenhauer, A., Zeman, F. & Boldt, J. Artificial intelligence in orthodontics: Evaluation of a fully automated cephalometric analysis using a customized convolutional neural network. Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics (2019).

Almansob, Y. et al. Patient’s facial soft tissue changes following the orthodontics treatment. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 18, 69–78 (2019).

Darkwah, W. K., Kadri, A., Adormaa, B. B. & Aidoo, G. Cephalometric study of the relationship between facial morphology and ethnicity. Translational Research in Anatomy 12, 20–24 (2018).

Franchi, L., Baccetti, T., De Toffol, L., Polimeni, A. & Cozza, P. Phases of the dentition for the assessment of skeletal maturity: a diagnostic performance study. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 133(3), 395–400 (2008).

Fishman, L. S. Chronological versus skeletal age, an evaluation of craniofacial growth. The Angle Orthodontist 49(3), 181–189 (1979).

Flores-Mir, C., Nebbe, B. & Major, P. W. Use of skeletal maturation based on hand-wrist radiographic analysis as a predictor of facial growth: a systematic review. The Angle Orthodontist 74(1), 118–124 (2004).

Baccetti, T., Franchi, L. & McNamara, J. A. Jr. The cervical vertebral maturation (cvm) method for the assessment of optimal treatment timing in dentofacial orthopedics. In Seminars in Orthodontics, volume 11, pages 119–129. (Elsevier, 2005).

Zhao, X.-G., Lin, J., Jiang, J.-H., Wang, Q. & Ng, S. H. Validity and reliability of a method for assessment of cervical vertebral maturation. The Angle Orthodontist 82(2), 229–234 (2012).

Kök, H., Acilar, A. M. & İzgi, M. S. Usage and comparison of artificial intelligence algorithms for determination of growth and development by cervical vertebrae stages in orthodontics. Progress in Orthodontics 20(1), 1–10 (2019).

Makaremi, M., Lacaule, C. & Mohammad-Djafari, A. Deep learning and artificial intelligence for the determination of the cervical vertebra maturation degree from lateral radiography. Entropy 21(12), 1222 (2019).

Amasya, H., Cesur, E., Yıldırım, D. & Orhan, K. Validation of cervical vertebral maturation stages: Artificial intelligence vs human observer visual analysis. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 158(6), e173–e179 (2020).

Seo, H., Hwang, J. Jeong, T. & Shin, J. Comparison of deep learning models for cervical vertebral maturation stage classification on lateral cephalometric radiographs. Journal of Clinical Medicine 10(16), 3591 (2021).

Atici, S. F. et al. Fully automated determination of the cervical vertebrae maturation stages using deep learning with directional filters. Plos one 17(7), e0269198 (2022).

Mohammad-Rahimi, H. et al. Deep learning for the classification of cervical maturation degree and pubertal growth spurts: A pilot study. Korean Journal of Orthodontics 52(2), 112–122 (2022).

Khalid, M. A. et al. Aariz cephalometric dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27986417.v1, 5 (2025).

Khalid, M. A. et al. Cepha29: automatic cephalometric landmark detection challenge 2023. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.04808 (2022).

Khan, R., Khalid, M. A., Zulfiqar, K., Bashir, U. & Fraz, M. M. Enhancing cephalometric landmark detection with a two-stage cascaded cnn on multi-resolution multi-modal data. In Annual Conference on Medical Image Understanding and Analysis, 3–18 (Springer, 2024).

He, T. et al. Cephalometric landmark detection by considering translational invariance in the two-stage framework. Neurocomputing 464, 15–26 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to all of the clinicians at Islamic International Dental College, Riphah International University for their tireless efforts and contributions to the annotation process of this dataset. This research would not have been possible without the support of Riphah International University, Islamabad, Pakistan. We also extend our sincere thanks to the patients who provided consent for the use of their cephalometric images. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the valuable feedback and suggestions provided by the anonymous reviewers, which helped us improve the quality of this dataset.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Muhammad Anwaar Khalid provided technical support to the clinical team, including dataset acquisition, management, and quality control. He facilitated the annotation process through hands-on involvement with LabelBox and technical validations. Kanwal Zulfiqar led the orthodontist team, acquired the dataset from multiple sources, ensured compliance with patient privacy regulations, and provided expert guidance to both labelers and reviewers. Ulfat Bashir oversaw the legal bindings governing the use of patient data in public research. Additionally, he contributed to the formulation of the research theme and the expected results. Areeba Shaheen and Rida Iqbal served as reviewers, assessing the precision and consistency of the annotated data during the reviewing phase. Zarnab Rizwan and Ghina Rizwan served as labelers, independently annotating the dataset during the labeling phase. Muhammad Moazam Fraz provided overarching supervision, refining the research direction and ensuring alignment with the broader objectives of the study. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khalid, M.A., Zulfiqar, K., Bashir, U. et al. A Benchmark Dataset for Automatic Cephalometric Landmark Detection and CVM Stage Classification. Sci Data 12, 1336 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05542-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05542-3