Abstract

Chrysosplenium macrophyllum Oliv., a perennial herb native to China, is widely used in traditional medicine for its notable therapeutic properties. However, the absence of a reference genome has constrained its full potential for research and application. This study presents the first chromosome-level de novo genome assembly of C. macrophyllum, constructed by integrating long reads from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), short reads from BGI, and Hi-C data. The final assembly spans 2.55 Gb, with a scaffold N50 of 93.38 Mb, and 83.70% of the genome has been assigned to 22 chromosomes. The mapping rate of the BGI short reads to the genome is approximately 97.94%, and BUSCO analysis reveals that 97.94% of the predicted genes are complete. A total of 62,921 protein-coding genes were predicted, with functional annotations for 93.67% of them. This chromosome-level genome assembly represents an important resource for expanding our understanding of Chrysosplenium species and supports future genomic studies and applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Chrysosplenium, a genus of small perennial herbaceous plants, occupies a distinctive position within the Saxifragaceae family1. Currently, there are approximately 80 species of Chrysosplenium worldwide, with the majority found in Asia, Europe, and North America in the northern hemisphere and a few species occurring in temperate regions of the Southern Hemisphere2,3,4. These species predominantly thrive in shady and humid habitats at altitudes ranging from 450 to 4800 meters, including alpine meadows, alpine shrubs, and high gravel gaps5. China is recognized as one of the centers of diversity for Chrysosplenium, harboring around 40 species, 24 of which are endemic to the country6. They are primarily distributed in the southwestern, northern, and central regions of China, with a significant concentration in the provinces of Shaanxi, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Xizang7. The genus Chrysosplenium, rich in various compounds such as flavonoids and triterpenes, has high medicinal value duo to its wide-ranging pharmacological properties, including anti-tumor, antibacterial, antiviral, hepatoprotective, and insecticidal activities8.

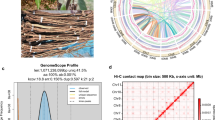

Chrysosplenium macrophyllum Oliv., is a perennial herbaceous plant belonging to the subgenus Alternifolia, and is a unique species native to China9 (Fig. 1a). Based on specimen records, it is mainly distributed in subtropical regions of China10. C. macrophyllum is a widely used folk herbal, traditionally employed in treating various ailments such as infantile convulsions, ecthyma, scalds, and lung and ear disorders6. While a pseudo-chromosome level genome for Tiarella polyphylla within Saxifragaceae family has been published, limited genomic information is available for species of the Chrysosplenium genus11. Previous research has predominantly focused on the chloroplast genome of Chrysosplenium, with no studies addressing its nuclear genome12,13,14,15,16. Furthermore, C. macrophyllum has received limited research attention, which has significantly hindered the development and utilization of its medicinal potential.

Genome assembly of Chrysosplenium macrophyllum. (a) Morphology of C. macrophyllum. (b). Flow cytometry histogram of Glycine max nuclei (FL2 signal, used as an internal reference). (c) Flow cytometry histogram of C. macrophyllum nuclei (FL2 signal). (d) Flow cytometry histogram of a mixed sample containing nuclei from both G. max and C. macrophyllum (FL2 signal), demonstrating clear peak separation for genome size estimation. (e) GenomeScope 2.0 profile of C. macrophyllum based on BGI short-read sequencing (k = 19), showing k-mer frequency distribution and estimated genome characteristics.

In this study, we have unveiled the whole-genome sequences of C. macrophyllum for the first time, achieved through the integration of Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) long reads, Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) short reads, and high-throughput chromatin conformation capture sequencing (Hi-C) reads. The assembled genome size is approximately 2.55 Gb, with a scaffold N50 length of 93.38 Mb. Of the assembled sequences, 83.70% (2.14 Gb) were anchored to 22 pseudo-chromosomes. The genome contains 62,921 protein-coding genes, with annotations available for 93.67% of them. Additionally, we identified 316 miRNAs, 2,768 tRNAs, 2,348 rRNAs, and 1,467 snRNA. This newly assembled genome serves a crucial resource for investigating the evolutionary history of Saxifragaceae, studying the biosynthesis of bioactive compounds, and exploring its potential medicinal value as a Chinese endemic plant.

Methods

Plant materials

We collected samples from Qizimei Mountain National Nature Reserve for BGI sequencing, ONT sequencing, Hi-C sequencing, and transcriptome sequencing, as well as for flow cytometry analysis. Materials for chromosome karyotype analysis came from Saiwudang National Nature Reserve. All voucher specimens are stored in the Herbarium of South-Central Minzu University (HSN).

Genome sequencing

To assemble and annotate the genome of C. macrophyllum, we combined short-read, long-read, Hi-C and transcriptome sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted from young leaves of C. macrophyllum using a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method17, and its concentration, purity, and integrity were assessed with a NanoDrop (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) and a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and 0.75% agarose gel electrophoresis. A short-read library was prepared using the VAHTS Universal Plus DNA Library Prep Kit for MGI V2 (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China), followed by sequencing on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform (BGI Inc., Shenzhen, China), generating approximately 457.28 Gb of raw data, with an estimated genome coverage of 143×.

To complement the short-read data, long-read sequencing was performed using Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT). High molecular weight DNA was fragmented using a Megaruptor, and DNA fragments were selected and ligated to adapters using the Nanopore SQK-LSK109 kit. Sequencing on the PromethION platform produced 269.58 Gb of long-read data from approximately 3 million reads (N50 = 29 kb, longest read = 834 kb).

Hi-C sequencing was applied to further improve the assembly by capturing chromatin interactions. Hi-C libraries were constructed with a modified Belton et al.18 workflow. Chromatin was cross-linked, digested, and labeled, with interacting DNA fragments captured using streptavidin magnetic beads. The Hi-C libraries were sequenced on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform (BGI Inc., Shenzhen, China), generating 355 Gb of data, which were used to assist in the subsequent of pseudochromosomes.

For transcriptome sequencing, RNA was extracted from roots, stems, and leaves of plants from the same population used for genomic sequencing. These RNA samples were pooled in equal proportions, followed by library preparation and sequencing on both the DNBSEQ-T7 (BGI Inc., Shenzhen, China) and PromethION platforms (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, USA). This generated 6.12 Gb and 12.39 Gb of raw data, respectively, providing valuable data for the subsequent genome annotation.

All library preparation and sequencing were conducted by Wuhan Benagen Technology Co. Ltd. (Wuhan, China).

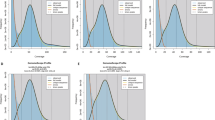

Genome size estimation

Genome size was first measured by flow cytometry (Sysmex CyFlow® Cube6) at Jiyuan Biotech Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China). A standard reference sample of Glycine max (Fig. 1b), with a known genome size, served as the benchmark. The analysis revealed that the genome size of C. macrophyllum is approximately 3.2 Gb (Fig. 1c,d). To further evaluate genome size, we carried out a k-mer–based genome survey. Raw BGI reads were quality-filtered with fastp v0.21.019, which removed adapters, short fragments and low-quality bases. We then counted 19-mers frequencies with Jellyfish v2.2.1020 and assessed genome characteristics using GenomeScope v2.021. The k-mer profile predicted a genome size of 3.19 Gb, a heterozygosity rate of 3.08%, and a duplication level of 89.26% (Fig. 1e).

Karyotype analysis

Karyotype analysis of C. macrophyllum was conducted at OMIX Technologies Corporation (Chengdu, China) to identify chromosome number and ploidy. Active root tip meristematic tissues were obtained by culturing collected C. macrophyllum plants. Root tips, approximately 1.5–2 cm in length, were collected and exposed to a nitrous oxide environment to induce mitosis, thereby increasing the number of cells in the metaphase stage. These root tips were then diced, digested, and treated with a mixture of 1% pectolyase Y23 and 2% cellulase Onozuka R-10. Cells were subsequently gathered via centrifugation and resuspended in 90% acetic acid. A drop of the cell suspension was placed on a slide, which was kept in a box lined with moist paper. Chromosomes were stained with the fluorescent dye 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Metaphase cells with well-dispersed chromosomes were counted using an Olympus BX63 fluorescence microscope. Further confirmation of chromosome number and ploidy was achieved through fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), employing telomeric repeats Oligo-(TTTAGGG)6 as probes for chromosome counting and 5S rDNA repeats for ploidy determination. Observations were made using the Olympus BX63 fluorescence microscope.

The karyotype analysis revealed that C. macrophyllum has a total of 88 chromosomes (Fig. 2a). FISH analysis using telomeric repeats probes showed clear fluorescent signals at the telomeres of various chromosomes, confirming the observed chromosome count of 88 (Fig. 2b). Additionally, FISH analysis with 5S rDNA repeat probes revealed that all cells in the sample exhibited 8 hybridization signals (Fig. 2c). Based on these findings, C. macrophyllum is confirmed to be an octoploid species with a chromosomal configuration of 2n = 8x = 88.

De novo genome assembly

The pipeline for the C. macrophyllum chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation is illustrated in Fig. 3. To assembly the contigs, low-quality Nanopore raw reads with a quality score below 7 were filtered out using Oxford Nanopore GUPPY v0.3.022. The remaining high-quality reads were then de novo assembled with NextDenovo v2.5.023. This initial assembly was corrected twice using Nanopore reads with the assistance of Racon v1.4.1124, followed by two additional rounds of correction using BGI reads with Pilon v1.2325. Duplicates were removed from the corrected genome using purge_dups v1.426, resulting in a draft genome size of 2.55 Gb, ready for further scaffolding, annotation, and analysis as detailed in Table 1.

Hi-C reads were first quality-filtered with fastp v0.21.019 to remove low-quality bases and other contaminants. The cleaned pairs were aligned to the draft genome with HICUP v0.8.027, and uniquely mapped reads were passed to ALLHiC v0.9.828 to cluster, order, and orient scaffolds into pseudo-chromosomes. Hi-C contact matrices were converted to binary (.hic) format with 3D-DNA v18041929 and Juicer v1.629; the resulting scaffolds were then visualised and manually curated in Juicebox v1.11.0830. In total, 1,298 contigs were anchored onto 22 pseudo-chromosomes, representing 83.70% of the assembled genome (Fig. 4a,b). The assembled chromosomes range from 60,630,240 bp to 135,182,039 bp in length (Table 2).

Genome prediction and annotation

Repetitive elements in the C. macrophyllum genome were annotated with a pipeline that integrated homology-based and de novo strategies. An initial repeat library was constructed using LTR_FINDER v1.0.731, LTRharvest v1.6232, and RepeatModeler v2.0.433. Unidentified sequences were typed with TEclass v2.1.334 and merged with Repbase v2018102635 database to yield the final library. This library was then used by RepeatMasker v4.1.536 to mask repetitive sequences within the genome and by RepeatProteinMask v4.1.5 (https://github.com/Dfam-consortium/RepeatMasker) to predict repeat sequences based on TE protein types. Tandem repeat sequences were identified using Tandem Repeats Finder v4.0937 and MISA v2.138. Comprehensive analysis revealed that repetitive elements comprised 2.13 Gb, or 83.23% of the total genome size (Table 3). Of this, interspersed repeats accounted for 1.78 Gb, or 69.69% of the genome, while tandem repeats occupied 345.84 Mb, representing 13.54% of the genome. Within the interspersed repeats category, DNA transposons constituted 13.41% of the genome, Long Interspersed Elements (LINEs) accounted for 4.67%, Short Interspersed Elements (SINEs) contributed 0.10%, and Long Terminal Repeat retrotransposons (LTRs) made up 64.76%. Among the LTR retrotransposons, LTR-Gypsy elements were the most prevalent, representing 30.14%, followed by LTR-Copia elements at 16.13% (Table 3).

Non-coding RNA, which lack protein-coding potential, was predicted through various approaches. For tRNA prediction, tRNAscan-SE v2.0.1239 was utilized, while rRNA prediction was performed using RNAmmer v1.240. To identify ncRNA, including snRNA and miRNA, INFERNAL v1.1.441 was applied, referencing the Rfam database. As a result, our annotation process identified a total of 316 miRNAs, 2,768 tRNAs, 2,348 rRNAs, and 1,467 snRNAs in the C. macrophyllum genome (Table 4).

The genome structure of C. macrophyllum was inferred through an integrative approach that combined ab initio, homology-based, and transcriptome-based predictions. For Ab initio prediction, Augustus v3.5.042 and GlimmerHMM v3.0.443 were applied. For homology-based prediction, protein sequences from Chrysosplenium sinicum, Kalanchoe fedtschenkoi, Kalanchoe laxiflora, Rhodiola crenulata, and Arabidopsis thaliana, were aligned to the the C. macrophyllum genome using tblastn v2.13.044, after which transcript and protein-coding region were refined with Exonerate v2.4.045. Transcriptome-based prediction combined BGI short reads and ONT full-length reads. Filtered BGI reads were mapped with HISAT2 v2.2.146 and assembled with StringTie v2.2.147. ONT reads were filtered using NanoFilt v2.8.048 and identified via Pychopper v2.7.5 (https://github.com/epi2me-labs/pychopper). The resulting sequences were aligned to the C. macrophyllum genome using minimap2 v2.26-r117549, and the resulting BAM files were reconstructed into transcripts using StringTie v2.2.147. The resulting assemblies were merged with TAMA v1.050, and open reading frames were identified using TransDecoder v5.7.0 (https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder). Finally, MAKER v3.01.0351 integrated the evidence from all three approaches to yield the consensus gene set. The resulting annotation comprises 62,921 protein-coding genes, with mean gene and CDS lengths of 4,086 bp and 1,123 bp, respectively; genes contain an average of 4.76 exons, with mean exon and intron lengths of 302 bp and 702 bp (Table 5).

Predicted protein sequences were compared with the UniProt and NCBI non-redundant (NR) databases using DIAMOND v2.1.852 to obtain high-confidence homologues. Conserved motifs and domains were identified with InterProScan v5.55–88.053, and complementary domain searches were carried out with HMMER v3.3.254. Gene Ontology (GO) terms were assigned by merging DIAMOND hits with InterPro-derived GO mappings in Blast2GO v4.155, and GO terms were subsequently linked to their corresponding Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) orthologues were predicted via the KAAS (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/kaas/) web server. Overall, 58,939 genes —representing 93.67% of the predicted protein-coding set —received functional annotation in at least one database, and 1,319 genes were annotated across all databases (Table 6).

Data Records

The raw sequencing data used for genome assembly and annotation have been deposited in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC)56,57, Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences/China National Center for Bioinformation, under the BioProject accession number PRJCA025550, and are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject. BGI short-reads, Oxford Nanopore reads, Hi-C reads, and RNA-seq data have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive58 in NGDC under the accession number CRR113620959, CRR113620860, CRR113621061/CRR113621162, and CRR113621263/CRR113621364, respectively. The chromosomal-level genome assembly data have been stored in GenBank with the accession number JBISEJ00000000065. Additionally, the genome annotation file is available in Figshare66.

Technical Validation

To evaluate the accuracy and completeness of the C. macrophyllum genome, two complementary strategies were applied. Quality-filtered BGI short reads were first remapped to the assembly with BWA v5.3.067, and 97.94% of reads aligned, indicating high alignment efficiency. Genome completeness was then evaluated with Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO v5.3.0)68 based on the embryophyta_odb10 reference set (1,614 conserved orthologues). The assembly contained 98.6% complete genes, of which 29.6% were single-copy and 69.1% were duplicated; only 0.6% were fragmented and 0.7% were missing (Table 7). An identical BUSCO analysis of the annotated gene set recovered 1,592 complete genes (98.6% completeness), comprising 656 single-copy (40.6%) and 936 duplicated (58.0%) genes (Table 7). Taken together, these results confirm that both the genome assembly and its annotation are highly complete and reliable.

Code availability

All data processing commands and pipelines were executed in accordance with the instructions and guidelines provided by the respective bioinformatic software. No custom scripts or code were used in this study.

References

Koldaeva, M. N. Chrysosplenium fallax (Saxifragaceae), a new species from the Russian Far East. Phytotaxa 491, 35–46 (2021).

Yang, T. et al. A comprehensive analysis of chloroplast genome provides new insights into the evolution of the genus Chrysosplenium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 14735 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. A new species of Chrysosplenium (Saxifragaceae) from Zhangjiajie, Hunan, central China. Phytotaxa 277, 287–292 (2016).

Wu, Z. et al. Analysis of six chloroplast genomes provides insight into the evolution of Chrysosplenium (Saxifragaceae). BMC Genomics 21, 621 (2020).

China, E. C. o. F. o. Flora of China. Vol. 34 234 (Science Press, 1992).

Xiang, N. et al. De novo transcriptome assembly and EST-SSR marker development and application in Chrysosplenium macrophyllum. Genes (Basel) 14, 279 (2023).

Fu, L., Liao, R., Lan, D., Wen, F. & Liu, H. A new species of Chrysosplenium (Saxifragaceae) from Shaanxi, north-western China. PhytoKeys 159, 127–135 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. A review of the genus Chrysosplenium as a traditional Tibetan medicine and its preparations. J Ethnopharmacol 290, 115042 (2022).

Pan, J. & Ohba, H. in Flora of China Vol. 8 Chrysosplenium L (eds Wu ZY & Raven PH) 346-358 (Science Press, 2001).

Global Biodiversity Information Facility, https://www.gbif.org/ (2024).

Liu, L. et al. Phylogenomic and syntenic data demonstrate complex evolutionary processes in early radiation of the rosids. Mol Ecol Resour. 23, 1673–1688 (2023).

Yan, W. et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Chrysosplenium nudicaule (Saxifragaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B 6, 3028–3030 (2021).

Yan, W., Liu, H., Yang, T., Liao, R. & Qin, R. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Chrysosplenium ramosum and Chrysosplenium alternifolium (Saxifragaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B 5, 2837–2838 (2020).

Yan, W. et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Chrysosplenium macrophyllum and Chrysosplenium flagelliferum (Saxifragaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B 5, 2040–2041 (2020).

Liao, R., Dong, X., Wu, Z.-H., Qin, R. & Liu, H. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Chrysosplenium sinicum and Chrysosplenium lanuginosum (Saxifragaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B 4, 2142–2143 (2019).

Kim, Y., Lee, J. & Kim, Y. The complete chloroplast genome of a Korean endemic plant Chrysosplenium aureobracteatum Y.I. Kim & Y.D. Kim (Saxifragaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B 3, 380–381 (2018).

Doyle, J. J. T. & Doyle, J. L. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12, 13–15 (1990).

Belton, J. M. et al. Hi–C: A comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods 58, 268–276 (2012).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun. 11, 1432 (2020).

Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M. & Holt, K. E. Performance of neural network basecalling tools for Oxford Nanopore sequencing. Genome Biology 20, 129 (2019).

Jiang, H. et al. An efficient error correction and accurate assembly tool for noisy long reads. bioRxiv, 2023.2003.2009.531669 (2023).

Vaser, R., Sović, I., Nagarajan, N. & Šikić, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 27, 737–746 (2017).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLOS ONE 9, e112963 (2014).

Guan, D. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 36, 2896–2898 (2020).

Wingett, S. et al. HiCUP: pipeline for mapping and processing Hi-C data. F1000Res 4, 1310 (2015).

Zhang, X., Zhang, S., Zhao, Q., Ming, R. & Tang, H. Assembly of allele-aware, chromosomal-scale autopolyploid genomes based on Hi-C data. Nature Plants 5, 833–845 (2019).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal3327 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst 3, 99–101 (2016).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res 35, W265–W268 (2007).

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 18 (2008).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. PNAS 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Abrusán, G., Grundmann, N., DeMester, L. & Makalowski, W. TEclass-a tool for automated classification of unknown eukaryotic transposable elements. Bioinformatics 25, 1329–1330 (2009).

Jurka, J. et al. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenetic Genome Res 110, 462–467 (2005).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using repeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 25, 4.10.11–14.10.14 (2009).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 27, 573–580 (1999).

Beier, S., Thiel, T., Münch, T., Scholz, U. & Mascher, M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 33, 2583–2585 (2017).

Chan, P. P., Lin, B. Y., Mak, A. J. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 49, 9077–9096 (2021).

Lagesen, K. et al. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 35, 3100–3108 (2007).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

Stanke, M., Diekhans, M., Baertsch, R. & Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24, 637–644 (2008).

Delcher, A. L., Bratke, K. A., Powers, E. C. & Salzberg, S. L. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 23, 673–679 (2007).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421 (2009).

Slater, G. S. C. & Birney, E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 6, 31 (2005).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol 37, 907–915 (2019).

Kovaka, S. et al. Transcriptome assembly from long-read RNA-seq alignments with StringTie2. Genome Biol 20, 278 (2019).

De Coster, W., D’Hert, S., Schultz, D. T., Cruts, M. & Van Broeckhoven, C. NanoPack: visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics 34, 2666–2669 (2018).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Kuo, R. I. et al. Illuminating the dark side of the human transcriptome with long read transcript sequencing. BMC Genomics 21, 751 (2020).

Holt, C. & Yandell, M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 491 (2011).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H. G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nature methods 18, 366–368 (2021).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240 (2014).

Mistry, J., Finn, R. D., Eddy, S. R., Bateman, A. & Punta, M. Challenges in homology search: HMMER3 and convergent evolution of coiled-coil regions. Nucleic Acids Res 41, e121–e121 (2013).

Conesa, A. et al. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676 (2005).

CNCB-NGDC Members and Partners. Database Resources of the National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res 50, D27–D38 (2022).

Chen, M. et al. Genome Warehouse: A Public Repository Housing Genome-scale Data. Genom Proteom Bioinf 19, 584–589 (2021).

Chen, T. et al. The Genome Sequence Archive Family: Toward Explosive Data Growth and Diverse Data Types. Genom Proteom Bioinf 19, 578–583 (2021).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA016278/CRR1136209 (2024).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA016278/CRR1136208 (2024).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA016278/CRR1136210 (2024).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA016278/CRR1136211 (2024).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA016278/CRR1136212 (2024).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA016278/CRR1136213 (2024).

Xiang, N. et al. Chrysosplenium macrophyllum isolate NX-2024a, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBISEJ000000000 (2024).

Xiang, N. The genome assembly annotation for the Chrysosplenium macrophyllum. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26299489.v2 (2024).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv: Genomics 00, 1–3 (2013).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32170207) and the construction plan of Hubei province science and technology basic conditions platform (No. BZZ23002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. L. and R. Q. designed the study and led the research. N. X. wrote the draft manuscript. N. X. and S. L. contribute to the genome assembly and annotation. T. Y. (Tao Yuan) and T. Y (Tiange Yang) participated in genome evolution analysis. H. L., T. Y. (Tao Yuan) and X. L. contributed substantially to the revisions. The final manuscript has been read and approved by all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiang, N., Yuan, T., Liu, S. et al. Chromosomal level genome assembly of medicinal plant Chrysosplenium macrophyllum. Sci Data 12, 1224 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05546-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05546-z