Abstract

Aeromedical evacuation (AE) is an invaluable tool for the transport of critically injured patients to care facilities. There is increasing evidence obtained from animal models and human patients that exposure to AE-relevant hypobaria within a few days of injury can worsen outcomes. The cause of this secondary injury is not well understood but it may be related to changes in gene expression induced by exposure to evacuation-relevant conditions. In order to explore the causes of secondary injury, gene expression induced by AE-relevant flight conditions was analyzed. Adult male rats were exposed to flight cabin-relevant hypobaria (8000 or 4000 ft equivalents) and/or different oxygen concentrations (21% or 100%) for 5 or 10 hr. At the end of the exposures, RNA was isolated from lung, blood, heart, and brain (hippocampus), levels of gene expression were measured via microarray analysis, and canonical pathway analysis identified the primary gene pathways enriched by the exposures. This information should be useful to not only optimize the health status of trauma patients undergoing aeromedical evacuation but also help determine which gene expression pathways could be modulated to optimize the therapeutic efficacy of the body’s endogenous protection and repair mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rapid aeromedical evacuation (AE) is often used for the transport of critically injured patients to medical facilities following on-site triage. The physiologic and cognitive impacts of such flights are incompletely understood, and there is experimental evidence that the transport itself could contribute to secondary injury to the brain and other organs1,2. Efforts to understand the mechanisms that cause AE-related secondary injury will potentially improve patient safety and outcomes by facilitating more accurate risk assessment related to the timing of evacuation and the development of mitigation strategies to counteract any identified negative effects.

Like most fixed wing aircraft, the cabins of planes used for AE are routinely pressurized up to a cabin altitude of approximately 8000 ft (2438 meters), which is well-tolerated by healthy individuals. Acute hypobaric exposure has a transient effect on mechanisms like oxygen transport in order to compensate for the increased pressure, and extended exposure can lead to long-term physiological adaptation3. But most studies into the pathophysiological effects of hypobaria involve exposure to extreme altitudes (>12,000 ft), such as those experienced by mountain climbers, to study the molecular basis of high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) and high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE)4,5. Conversely, the effects from less extreme AE-relevant hypobaria are more obscure.

The most commonly cited explanation for adverse effects of hypobaria is systemic hypoxia and associated impairment of O2 delivery to vital organs6,7. Thus, critical care practitioners often provide supplemental O2, sometimes up to 100%, to avoid systemic hypoxia. However, supplemental O2 in excess of what is necessary to avoid hypoxia can be toxic due to the production of reactive oxygen species and subsequent tissue damage caused by increased oxidative stress. Some studies have reported worse outcomes in brain injured rats when exposed to hyperoxic hypobaria in comparison to normoxic hypobaria8,9. Moreover, hyperoxia is associated with increased mortality in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke, and resuscitation following cardiac arrest10,11. Retrospective clinical studies provide evidence for increased in-hospital mortality for patients treated with hyperoxic ventilation, although results from some subgroups of patients, including those with TBI, are inconclusive12,13.

The effect of hypobaria post-injury is worthy of exploration, however injury causes an inflammatory cascade that may conceal the effects induced by the hypobaric transit itself. For instance, exposure to repeated AE-relevant hypobaria has its own observable effects in the healthy (non-injured) human brain14,15. These changes may have little acute impact on healthy individuals, but they could have a deleterious consequences on already-injured patients as hypobaria itself can cause adverse effects on multiple organs16,17,18,19, particularly after TBI2,8,20. There is growing evidence obtained from lab animal studies that exposure to hypobaria within a few days after trauma can exacerbate physiological and cognitive deficits8,9,17,20,21,22 and increase inflammatory signaling2,17 compared to animals maintained under normobaric conditions2,8,16,17,18,19,20.

The goal of this study was to analyze gene expression in the lungs, heart, blood, and brain (hippocampus) of rats immediately following exposure to AE-relevant conditions, including level of hypobaria (mild: 4000 ft/1219 m equivalent or 654 mmHg; moderate: 8000 ft/2438 m equivalent or 562 mmHg), for durations of 5 and 10 hr, under normoxic (21% O2) or hyperoxic (100% O2) conditions20.

Methods

Exposure of rats to hypobaria and/or hyperoxia

The animal use protocol was reviewed and approved by the U.S. Air Force Surgeon General’s Office of Research Oversight and Compliance (FWR-2018-0001A) and by the University of Maryland, Baltimore Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (1217007). These studies were conducted in a facility accredited by AAALAC, in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NRC, 2011) and were performed in compliance with DODI 3216.1.

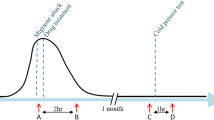

Adult (3–6 months) male Sprague Dawley rats (Inotiv, Inc, West Lafayette, IN) weighing 300–350 g were placed in a flight chamber and exposed to normobaria (767 mmHg; 0 ft altitude equivalent), or two levels of hypobaria, 654 mmHg or 562 mmHg (equivalent to 4000 ft and 8000 ft altitude, respectively)8, for 5 or 10 hr. The chamber pressure was decreased incrementally over the initial 30 min to simulate ascent and increased over the final 30 min to simulate descent. The chamber was also perfused with either air (21% O2; normoxia) or 100% O2 (hyperoxia) throughout the simulated “flight.” Immediately after descent, rats received 4–5% isoflurane until completely anesthetized followed by euthanasia via decapitation. Lung, heart, and hippocampus tissues were collected and snap frozen on dry ice before storage at −80 °C. Blood was collected in PAXgene tubes (Qiagen, Santa Clara, CA) and stored at −80 °C.

RNA isolation and quantification

Samples of about 50–100 mg were collected from heart (lower apex), lung (lower apex of right inferior lobe), and hippocampus and placed into −80 °C RNAlater™ ICE (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and stored at −20 °C overnight. The following day, tissue was homogenized on ice and RNA was isolated with TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher) and PureLink™ mRNA mini kit (Thermo Fisher) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Blood mRNA was isolated according to manufacturer’s PAXgene Blood RNA protocol. DNase was added to columns to prevent DNA contamination. Isolated RNA was then quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher), and quality and integrity of RNA samples was assessed by an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) at the UMB Center for Innovative Biomedical Resources (CIBR). RNA was required to achieve an RNA integrity number of 7 or higher before microarray analysis.

Microarray hybridization

Microarray profiling of lung, heart, and blood RNA was performed using Clariom S Rat Assays (Thermo Fisher), while profiling of hippocampus RNA was performed using Rat Gene 2.0 ST Array chips (Thermo Fisher), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 150 ng RNA was transcribed to double-stranded cDNA, followed by synthesis and purification of cRNA. 2nd-cycle ss-cDNA was then synthesized and then purified after RNA hydrolysis using RNase H. ss-cDNA was fragmented and labeled before hybridization onto the microarray chips, which were washed and processed using an Affymetrix GeneChip system 3000 7 G (Thermo Fisher) to generate CEL files.

Analysis of microarray files

Affymetrix image data (CEL files) was analyzed by the UMB Institute for Genome Sciences using the R statistical analysis tool. The R ‘oligo’ package23 was used to access the intensity values which were normalized using the ‘Robust Multichip Average (RMA)’ normalization method provided by the R’limma’ package24. The samples were assessed and corrected for any batch effects before downstream analyses (see USAGE NOTES). A general linear model was utilized to fit the expression values for each gene. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to identify outliers through visual inspection for downstream exclusion (Fig. 1). The absence of noticeable grouping indicates that there was no obvious driver of sample distribution beyond biological variation. The same analysis was performed for all tissues with final n-values listed in Table 1. Subsequent tables and figures reflect final groups excluding outliers in all tissues.

Principal Component Analysis of Rat Lung Microarray Data. PCA plots showing clustering of lung RNA samples from all treatment groups. Samples are characterized into simulated altitude (0 ft, 4000 ft, or 8000 ft), oxygen (21% or 100%), and duration of exposure (5 hr or 10 hr). (a) The first and second components of all 60 samples are shown. Samples within the red square were identified as outliers and were not considered for differential expression analysis or qPCR validation. (b) The first and second components of samples after removing outliers are shown.

Statistical analysis

The R ‘limma’ package uses a moderated t-statistic test based on a Bayesian model to assess differential expression. In order to focus on transcripts that showed the greatest change and therefore most likely reflect physiological response to the treatments, initial thresholds were set at >1.5x change (positive or negative) with p-values < 0.1 compared to the baseline group (Altitude: 0 ft; Duration: 5 hr; Oxygen: 21%). P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method in R. The total number of up- or down-regulated transcripts in each tissue based on these thresholds are listed in Table 2. The identified transcripts were then utilized to assess pathway enrichment using QIAGEN Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (QIAGEN Inc., Santa Clara, CA; https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/IPA)25. The significant pathways enriched were selected using a 5% p-value cut-off. Heatmaps indicating pathway enrichment based on treatment group for lung (Fig. 2), heart (Fig. 3), blood (Fig. 4), and hippocampus (Fig. 5) are available for reference. All figures were generated using the R statistical analysis tool.

Reverse transcription and microarray validation with qPCR

Reverse transcription of 1 µg lung RNA was carried out with High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Thermo Fisher) according to manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed using primers designed through the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) primer design tool (Table 3) and purchased from IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). Primers and annealing temperatures (Ta) were optimized to ensure efficiency was between 90% and 110% (Table 1). qPCR was performed with PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) on a QuantStudio 3 qPCR machine (Thermo Fisher) using the following protocol: initialized with 50 °C for 2 min then 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 15 s at the primers’ respective annealing temperatures, and 72 °C for 1 min. Relative quantification was performed using the QuantStudio 3 software (Thermo Fisher) to compare treatment groups against the control group. β-Actin used as a housekeeping transcript to normalize gene expression.

A diagram of the entire workflow can be found in Fig. 6.

Data Records

All individual microarray CEL files associated with this study are available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession number GSE26313126. All microarray sample files, including those designated as outliers, are included. The metadata record for each sample is also available at that location and a brief description of the dataset can be found in Table 4.

Technical Validation

After removal of outliers identified by PCA, qPCR validation was performed on specific transcripts using the same RNA samples that were submitted for microarray analysis in order to assess the quality of microarray results. Validation focused on the lung mRNA results. Candidates selected for validation were DE genes that either are known to be responsive to oxidative stress (ex. Hif3a, Osgin1, Sod3) or were identified as DE genes in 2 or more treatment groups. Gene expression was normalized to β-actin (Actb) expression and compared to baseline samples to determine fold-change. In total, 69% of the transcripts tested both agreed with the direction (increase or decrease) of the expression and exceeded the fold-change of the microarray analysis compared to baseline. 28% of transcripts matched with the direction of differential expression but the magnitude of the fold-change did not meet that of the microarray analysis. Only 1 transcript in 1 group completely contradicted the microarray results (Table 5). Considering the increased sensitivity of qPCR as compared to microarray, we concluded that these results are adequate to validate the microarray analysis27.

Usage Notes

Microarray analysis is a useful tool for broad-scale gene expression analysis, but it can be an expensive and time-consuming process. This study includes an extensive sample list across multiple tissues and should be useful for research into exposure of healthy or injured animals and humans to these AE-relevant conditions. The canonical pathway analysis provided can be used as an initial reference point for identifying pertinent pathways or mechanisms within each tissue before exploring the raw data itself. Along with the CEL files, TXT files featuring the results of pair-wise comparisons between each treatment group after removal of outliers and the respective tissue’s control group (Altitude: 0 ft; Duration: 5 hr; Oxygen: 21%) are available at GEO26.

Although batch correction was not needed for the vast majority of the data, the hippocampus microarray analyses were performed at different times and therefore were completed using different manufacturing lots of the Rat Gene 2.0 ST Array chips. The hippocampus files should therefore be separated into 2 batches as noted in the sample list (Table 4) and corrected before further analysis.

It should be noted that this study has several limitations. The qPCR validation was performed to assess the quality of the microarray using the same RNA samples, so these data have not been validated with new animals. The experiments only included young male rats, therefore the data may not reflect gene expression in female or older animals. This study was also limited to 2 durations of relatively mild exposure. Although gene expression was altered acutely through exposure to hypobaria and/or hyperoxia, later time points could further elucidate the effects these environments induce in the longer term as well as create a longer timeline in which to identify trends. Exposure to mild atmospheric perturbations for 10 h may not be long enough to observe all downstream effects of some genetic cascades, such as the cellular hypoxia response.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of Maryland-Baltimore Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (1217007) and the U.S. Air Force Surgeon General’s Office of Research Oversight and Compliance (FWR-2018-0001A). Animals were handled, and studies were conducted, under a program of animal care accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International and in accordance with the National Research Council’s 2011 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (in compliance with Department of Defense Instruction 3216.1).

Code availability

The microarray CEL files associated with these samples are publicly available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession number GSE26313126. No custom codes were used for this study.

References

Morris, M. Transport considerations for the head-injured patient: Are we contributing to secondary injury? Air Medical Journal. 11(7), 9–13 (1992).

Goodman, M. D. et al. Traumatic Brain Injury and Aeromedical Evacuation: When is the Brain Fit to Fly? Journal of Surgical Research. 164(2), 286–93 (2010).

Murray, A. J., Montgomery, H. E., Feelisch, M., Grocott, M. P. W. & Martin, D. S. Metabolic adjustment to high-altitude hypoxia: from genetic signals to physiological implications. Biochem Soc Trans. 46(3), 599–607 (2018).

Luks, A. M., Swenson, E. R. & Bärtsch, P. Acute high-altitude sickness. European Respiratory Review. 26(143), 160096 (2017).

Sharma, M., Singh, S. B. & Sarkar, S. Genome Wide Expression Analysis Suggests Perturbation of Vascular Homeostasis during High Altitude Pulmonary Edema. PLOS ONE. 9(1), e85902 (2014).

Hodkinson, P. D. Acute exposure to altitude. J R Army Med Corps. 157(1), 85–91 (2011).

Johannigman, J. et al. Hypoxemia during aeromedical evacuation of the walking wounded. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 79(4) (2015).

Skovira, J. W. et al. Simulated Aeromedical Evacuation Exacerbates Experimental Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 33(14), 1292–302 (2016).

Proctor, J. L. et al. Aeromedical evacuation-relevant hypobaria worsens axonal and neurologic injury in rats after underbody blast-induced hyperacceleration. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 83(1 Suppl 1), S35–s42 (2017).

Damiani, E. et al. Arterial hyperoxia and mortality in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care. 18(6), 711 (2014).

O’Reilly, M. DNA damage and cell cycle checkpoints in hyperoxic lung injury: Braking to facilitate repair. American journal of physiology: Lung, cellular, and molecular physiology. 281, L291–305 (2001).

Ni, Y.-N., Wang, Y.-M., Liang, B.-M. & Liang, Z.-A. The effect of hyperoxia on mortality in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta analysis. BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 19(1), 53 (2019).

Baekgaard, J. S. et al. Early hyperoxemia is associated with lower adjusted mortality after severe trauma: results from a French registry. Crit Care. 24(1), 604 (2020).

McGuire, S. A. et al. Lower neurocognitive function in U-2 pilots: Relationship to white matter hyperintensities. Neurology. 83(7), 638–45 (2014).

McGuire, S. A. et al. White matter hyperintensities and hypobaric exposure. Ann Neurol. 76(5), 719–26 (2014).

Scultetus, A. H. et al. Histopathological Evidence of Multiple Organ Damage After Simulated Aeromedical Evacuation in a Swine Acute Lung Injury Model. Military Medicine. 185(Supplement_1), 57–66 (2020).

Dayani, Y. et al. Hypobaria during aeromedical evacuation exacerbates histopathological injury and modifies inflammatory response in rats exposed to blast overpressure injury. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 87(1), 205–13 (2019).

Goodman, M. D. et al. Hypobaric hypoxia exacerbates the neuroinflammatory response to traumatic brain injury. J Surg Res. 165(1), 30–7 (2011).

Tchantchou, F., Miller, C., Goodfellow, M., Puche, A. & Fiskum, G. Hypobaria-Induced Oxidative Stress Facilitates Homocysteine Transsulfuration and Promotes Glutathione Oxidation in Rats with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 13, 1179573520988193 (2021).

Proctor, J. L. et al. Air-Evacuation-Relevant Hypobaria Following Traumatic Brain Injury Plus Hemorrhagic Shock in Rats Increases Mortality and Injury to the Gut, Lungs, and Kidneys. Shock. 56(5), 793–802 (2021).

Scultetus, A. H. et al. Hypobaria during long-range flight resulted in significantly increased histopathological evidence of lung and brain damage in a swine model. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 86(1), 116–22 (2019).

Lopez, K. et al. Hypobaria Exposure Worsens Cardiac Function and Endothelial Injury in AN Animal Model of Polytrauma: Implications for Aeromedical Evacuation. Shock. 56(4), 601–10 (2021).

Carvalho, B. S. & Irizarry, R. A. A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics. 26(19), 2363–7 (2010).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Research. 43(7), e47–e (2015).

Krämer, A., Green, J., Pollard, J. Jr. & Tugendreich, S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 30(4), 523–30 (2013).

Borcar, A., Tchantchou, F., Shetty, A. C., Mahurkar, A. & Fiskum, G. GEO. https://identifiers.org/geo/GSE263131 (2024).

Morey, J. S., Ryan, J. C. & Van Dolah, F. M. Microarray validation: factors influencing correlation between oligonucleotide microarrays and real-time PCR. Biol Proced Online. 8, 175–93 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official guidance or position of the United States Government, the Department of Defense, the United States Air Force, or the United States Space Force. Supported by US Air Force FA8650-15-2-6D20 & FA8650-18-2-6H15. The authors would like to thank the staff at the University of Maryland Center for Innovative Biomedical Resources (CIBR) for their contribution to this work. This research was supported by the US Air Force: FA8650-15-2-6D20 & FA8650-18-2-6H15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B. and F.T. collected and prepared laboratory samples, A.S. and A.M. compiled and analyzed the data and generated the figures, and A.B. and G.F. developed the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borcar, A., Tchantchou, F., Shetty, A.C. et al. Acute Changes in Rat Tissue Gene Expression Following Exposure to Flight Relevant Hypobaria. Sci Data 12, 1289 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05570-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05570-z