Abstract

Endometriosis affects approximately 190 million females of reproductive age worldwide. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has been recommended as the primary non-invasive diagnostic method for endometriosis. This study presents new female pelvic MRI multicenter datasets for endometriosis and shows the baseline segmentation performance of two auto-segmentation pipelines: the self-configuring nnU-Net and RAovSeg, a custom network. The multi-sequence endometriosis MRI scans from two clinical institutions were collected. A multicenter dataset of 51 subjects with manual labels for multiple pelvic structures from three raters was used to assess interrater agreement. A second single-center dataset of 81 subjects with labels for multiple pelvic structures from one rater was used to develop the ovary auto-segmentation pipelines. Uterus and ovary segmentations are available for all subjects, endometrioma segmentation is available for all subjects where it is detectable in the image. This study highlights the challenges of manual ovary segmentation in endometriosis MRI and emphasizes the need for an auto-segmentation method. The dataset is publicly available for further research in pelvic MRI auto-segmentation to support endometriosis research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

According to key facts released by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2023, endometriosis affects approximately 190 million females of reproductive age worldwide1. The prevalence is often considered to be underestimated because the gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis relies on a surgical procedure called laparoscopy, which is not a routine examination2,3. Typically, only hospitalized female patients experiencing related symptoms such as chronic pelvic pain, abnormal cramping, and bleeding may undergo this procedure4. Ultrasound and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) have been recommended as the primary non-invasive diagnostic methods for endometriosis5. MRI can achieve over 90% diagnostic sensitivity and specificity in most cases6,7. An endometrioma on the ovary is a cystic lesion, affecting 17–44% of women diagnosed with endometriosis8. It can lead to infertility in some patients. Therefore, precise ovary segmentation based on three-dimensional (3D) MRI for endometriosis patients is crucial for endometrioma detection, surgical guidance, and predicting post-operative complications. In endometriosis patients, the ovary may be deformed or absent due to surgical resection, making this segmentation task challenging and underscoring the importance of experienced clinicians.

Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of deep learning methods in pelvic organ segmentation using MRI, particularly for prostate cancer and cervical cancer9,10,11,12. A recent study explored a U-Net-based ensemble method for the endometriotic lesions segmentation using ultrasound13. However, automatic ovary segmentation methods for endometriosis patients based on MRI are scarce. Given the advancements in deep learning algorithms for medical imaging segmentation, an automatic segmentation pipeline for endometriosis MRI would be highly beneficial. Such a pipeline could reduce the manual labeling workload for clinicians and help standardize ovary segmentation for endometriosis, thereby minimizing inter-rater disagreement. The residual learning network, ResNet, is a highly influential deep convolutional network that has achieved high accuracy in disease diagnosis and organ detection based on MRI14,15. Attention U-Net, known for its stability and practical utility, is widely adopted in medical image segmentation applications16,17. Typically, training an auto-segmentation model requires an annotated dataset. Even though some recent studies based on the Segment Anything model have achieved advancements in medical imaging auto-segmentation, their methods require manually selected bounding boxes as prompts or extensive fine-tuning to effectively utilize text prompts relevant to this problem, making it challenging to achieve excellent performance with a limited dataset size18,19,20. Therefore, another U-Net-based model, nnU-Net, recognized as a state-of-the-art approach for various medical image segmentation tasks, has been widely adopted as a baseline for automatic segmentation21,22.

In this study, we constructed two endometriosis MRI datasets: a multicenter dataset and a single-site dataset, sourced from two distinct clinical institutions. The first endometriosis MRI dataset, which includes multi-rater annotations of pelvic organs, was used to assess inter-rater agreement and establish a baseline for ovary segmentation performance by comparing human raters with a state-of-the-art automatic segmentation method. In addition, the second dataset can serve as the foundation for developing the auto-segmentation method. Utilizing this dataset, we propose an automatic ovary segmentation pipeline, RAovSeg, for endometriosis patients by combining a ResNet-based classifier with an Attention U-Net-based segmentation network to ensure the dataset is suitable for developing an auto-segmentation method. We also adopted the nnU-Net as the baseline model.

This pipeline can aid in detecting and segmenting the ovary for endometriosis treatment, including surgical guidance. It highlights the importance of observing ovarian abnormalities in patients with superficial endometriosis and assists in predicting post-operative complications when an ovary is resected. Given the current lack of publicly accessible datasets for endometriosis MRI, this dataset will be a valuable resource for future studies on endometriosis screening and treatment, especially for developing multi-organ segmentation methods for endometriosis.

Methods

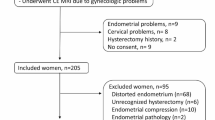

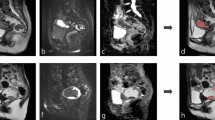

This is a retrospective study. Our dataset comprises multi-sequence MRI scans collected from two clinical institutions in Texas: The Memorial Hermann Hospital System and Texas Children’s Hospital Pavilion for Women. Although both datasets were from patients suspected of having endometriosis, they include different MRI sequences obtained using varying protocols and MRI scanners. The study and data sharing policy allowing sharing for research purposes was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at UTHealth (protocol no HSC-SBMI-22-0184), which includes requirements for patient informed consent. Figure 1 shows examples of MRI scans and the corresponding labels for two Datasets.

Image acquisition

Table 1 presents a summary of the two datasets collected in this study. The first dataset consists of MRI scans and labels for 51 patients before 2022. MR scans in this dataset were collected from 15 different sites using nine scanner models from three vendors (GE, Philips, and Siemens) with two magnetic field strengths (1.5 T and 3 T). Each site imaged a median of 3 subjects, ranging from 2 to 8. Each scanner model imaged a median of 4 subjects, ranging from 2 to 18. The MRI sequences include T2-weighted and T1-weighted fat suppression MRI. It is important to note that patients in this dataset were suspected of having endometriosis before undergoing MRI scans, resulting in eight patients who were not diagnosed with endometriosis. The second dataset comprises MRI scans and labels for 81 endometriosis patients from 2022. All the MRIs were taken in a single site with a Philips Ingenia 1.5 T MRI scanner. The MRI sequences in this dataset include T2-weighted, T2-weighted fat suppression, T1-weighted, and T1-weighted fat suppression MRI.

Data processing

Both datasets are de-identified by converting DICOM files to NIfTI format. The labels were manually contoured based on different MRI sequences by different raters in 3DSlicer. For the first dataset, three raters manually contoured structure segmentations for the uterus, ovaries, and endometriomas. The uterus and ovaries were contoured prioritizing based on T2-weighted sequences, while endometriomas were contoured prioritizing T1-weighted fat suppressed sequences. Note that in all cases, both T1 and T2 sequences were used. An experienced abdominal radiologist proposed a segmentation contouring guideline and reviewed the final labels from different raters to make necessary corrections. Manual segmentations from different raters are used to analyze interrater agreement. Each subject had one to two MRI sequences with two to four labels when the structures were present. Among the 51 subjects in Dataset 1, 11 (22%) were annotated by three raters, 22 (43%) by two raters, and 18 (35%) by one rater. For the second dataset, the uterus, ovaries, cysts, and endometriomas were manually contoured by an obstetrician-gynecologist assistant supervised by an expert Gynecologist, with all structures contoured based on T2-weighted fat suppression MRI with the same protocol. Although all patients in this dataset were diagnosed with endometriosis, only 12 had endometriomas.

Following patient enrollment and data collection, two specific analyses were conducted using the two datasets, respectively. Given that Dataset 1 was annotated by multiple raters, we used it to evaluate inter-rater agreement and to investigate how endometriosis may affect the segmentation accuracy of surrounding organs. For this analysis, seven subjects were selected from Dataset 1 based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) availability of a T2-weighted MRI; (2) suspected endometriosis; (3) manual segmentation of the ovaries and uterus by three raters. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the segmentation was contoured by fewer than three raters; (2) ovarian segmentation covered obvious endometriomas or cysts.

Another key analysis involved developing an automatic ovary segmentation pipeline and evaluating its performance. Since all subjects in Dataset 2 were collected and annotated using a standardized protocol, this dataset was used to ensure consistency and reliability. A total of 38 subjects from Dataset 2 were included for pipeline development, with 30 cases used for training and validation, and 8 cases reserved for testing, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were: (1) patients diagnosed with endometriosis and (2) availability of a T2-weighted fat suppression MRI with a corresponding manual ovary segmentation. The exclusion criteria were (1) patients with obvious endometriomas and (2) patients with cysts.

Data Records

The raw data for each subject is available on Zenodo in NIFTI format23. The data from the first institution can be found in the /D1_MHS directory, where each subject’s subfolder contains registered MRI scans from different sequences and the corresponding labels contoured by multiple raters, identified by their rater IDs. The MR Scanner information is available in the /D1_MHS directory. The data from the second institution is in the /D2_TCPW directory, where each subject’s subfolder contains registered MRI scans and corresponding labels. Since these labels were contoured by a single rater, no rater ID is included in the second dataset.

Technical Validation

Interrater agreement analysis

To assess interrater agreement for the uterus and ovaries as the two most critical surrounding anatomical structures affected by endometriosis using the first dataset, we use Krippendorff’s alpha at a nominal level based on the binary segmentation maps for each voxel to evaluate the reliability of segmentations provided by three raters24. Additionally, we assess pairwise interrater reliability using Gwet’s AC225. Evaluation metrics are calculated for the uterus and ovaries to assess their segmentation quality. The interrater agreement was generally acceptable among all raters, with a Krippendorff’s α value of 0.73 for the uterus, while it was only 0.46 for the ovaries. The manual segmentations from three raters in the first dataset were evaluated by calculating the DSC. The average DSC value is 0.73 ± 0.18 for the uterus and 0.48 ± 0.24 for the ovaries. The average volume is 220.3 ± 120.2 cc for uterus segmentation and 12.2 ± 6.5 cc for ovaries segmentation. Table 2 shows the summary of the average performance for all raters. Compared with the uterus, the ovary in smaller volume shows lower DSC and lower interrater agreement for manual segmentation. Another measurement of interrater reliability also shows the same trend. The Gwet’s AC2 ranged from 0.85 to 0.87 with a median of 0.86 for the uterus and ranged from 0.67 to 0.83 with a median of 0.72 for the ovaries. Figure 2 shows pairwise agreement between all pairs of raters for two structures in the first dataset. Figure 2(a,b) show pairwise segmentation quality and similarity using DSC, and Fig. 2(c,d) show pairwise interrater agreement using Gwet’s AC2.

According to our interrater agreement analysis using Krippendorff’s α and Gwet’s AC2, we found that ovary segmentation had significantly lower interrater agreement compared to uterus segmentation, which has a larger volume and a more consistent location and shape. Additionally, Krippendorff’s α for ovary segmentation was less than 0.67, indicating moderate levels of agreement. Even under the guidance of an expert, different raters did not achieve a high level of agreement when contouring the ovary based on MRIs. This highlights the challenges of manual ovary segmentation and puts the segmentation performance of an automated ovary segmentation tool in perspective. Furthermore, evaluating inter-rater agreement for endometrioma segmentation will be considered as future work once additional subjects are enrolled.

Auto-segmentation method

Data preprocessing

The selected subjects from the second dataset are used to develop the auto-segmentation method. The data were partitioned at the patient level into separate training, validation, and test sets to ensure subject-level independence across subsets. By developing our proposed auto-segmentation pipeline, we can demonstrate that our dataset is suitable for developing deep learning methods for medical imaging segmentation that could outperform the state-of-the-art methods. In the first step, we clipped the MRIs from the 1st to the 99th percentile and normalized them to a range of 0 to 1 for both datasets. For the auto-segmentation pipeline, the MRIs in dataset 2 are further preprocessed to enhance the representation of the ovaries, as described in the following equation.

By analyzing the normalized dataset, we identified a range of intensity values, from a minimum intensity (o1) to a maximum intensity (o2), corresponding to the ovaries and related structures. For each voxel x, if its original intensity I0 falls within the range \({o}_{1}\le {I}_{0}(x) < {o}_{2}\), its intensity is set to 1 to highlight regions with features similar to those of the ovaries. The intensity is maintained if the original intensity of voxel x is less than 0.5 and outside the range (\({o}_{1}\), \({o}_{2}\)). For voxels with an original intensity greater than 0.5, the intensity is inverted to 1−I0 to reduce the impact of high-intensity values while preserving structural information. Analysis of the MRI scans in 3DSlicer revealed that the intensity of the ovaries in our dataset ranges from 0.22 to 0.3. In this study, we set \({o}_{1}=0.22\) and \({o}_{2}=0.3\) for all MRIs in the auto-segmentation pipeline to achieve optimal performance. This preprocessing method replicates the adjustments that radiologists typically make when reviewing MRI scans.

Data resampling and augmentation methods were applied at the slice level. Each slice was resampled to a height and width of 512 pixels, with a voxel size of 5 mm by 5 mm. Random translations within 25 pixels and rotations of up to 25 degrees were applied to increase the training dataset size by a factor of five.

Auto-segmentation pipeline

The overview of RAovSeg is illustrated in Fig. 3. Our auto-segmentation pipeline was trained on a single NVIDIA A100 GPU with 40 GB of memory using PyTorch 3.9. The first part of our method is the classifier, which we refer to as ResClass. It was trained on 2D MRI slices from all training subjects, utilizing 3,252 slices for training and 2,168 slices for validation. The model architecture is a two-layer 2D ResNet18 with 8 and 16 features in the respective layers. Binary Cross Entropy with Logits Loss (BCEWithLogitsLoss) was used to train the classifier.

To mitigate overfitting, we increased the size of the validation set, incorporated a dropout layer with a probability of 0.2, and applied L2 regularization. In the second step, the segmentation model, which we refer to as AttUSeg, was trained exclusively on MRI slices containing ovaries and their corresponding labels, comprising 594 MRI slices for training and 136 MRI slices for validation. This model was developed using a four-layer Attention U-Net architecture, with 16, 32, 64, and 128 features in each layer. The Focal Tversky Loss function, with parameters α = 0.8, β = 0.2, and γ = 1.33, was employed for training26. This loss function is particularly advantageous for segmenting small structures, such as the ovaries in our dataset, due to its ability to balance false positives and false negatives. After generating outputs from the segmentation model, two postprocessing methods—closing operation and connected component analysis—were applied to reduce false positive predictions.

Evaluation metrics

We use the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) to evaluate segmentation quality. The interrater agreement is assessed using pairwise DSC calculations and the average DSC.

The average DSC is calculated using Equation 2, where DSCij represents the pairwise DSC between the segmentations contoured by rater i and rater j.

Quantitative analysis

Our quantitative analysis calculates the average DSC between the 3D segmentation outputs of all test subjects and their corresponding manual segmentations. The ablation study for RAovSeg is presented in Table 3. RAovSeg consists of the preprocessing, ResClass, AttUSeg, and postprocessing methods, achieving the highest DSC at 0.290. When the postprocessing method is removed, the remaining components, including our preprocessing method, ResClass, and AttUSeg, achieve a DSC of only 0.235. The DSC decreases further to 0.013 when ResClass is also removed, leaving only the preprocessing methods and AttUSeg. This result highlights the critical importance of ResClass in our pipeline. We also evaluated the impact of our proposed preprocessing and postprocessing methods on the performance of nnU-Net. The results of this ablation study are presented in Table 4. We used the 3D full-resolution nnU-Net to generate the ovary segmentation map, resulting in a DSC of 0.272. For comparison, we also applied our proposed preprocessing and postprocessing methods to the uuU-Net framework. However, these methods did not lead to noticeable improvement in U-Net’s performance, yielding DSC values of 0.267 and 0.200, respectively. The RAovSeg achieved a DSC of 0.290 for ovary segmentation, which outperforms nnU-Net.

Qualitative analysis

Figure 4 shows an example of the segmentation results before and after applying the postprocessing method. Compared to the segmentation results before postprocessing, the results after postprocessing have fewer false positives in the bottom right region, which corresponds to the intestinal tract. However, postprocessing increases the number of false positives near our segmentation target, the ovary, due to the influence of adjacent slices. Although the postprocessing method significantly enhances segmentation performance by reducing false positives, some false positives remain in some cases. Figure 5 shows the segmentation results for three subjects. For Subject A, both our proposed method and nnU-Net successfully detect the ovary’s position and shape. They achieve comparable performance. For Subject B, our proposed method precisely predicts the ovary’s position, size, and shape, though some false positives are generated. In contrast, nnU-Net predicts only parts of the ovary with a much smaller volume than manual segmentation. In Subject C, the ovary has an irregular shape. Our method detects the ovary with an inaccurate shape in one of the two slices shown in this figure, while nnU-Net fails to predict the ovary in this subject.

The comparison of the segmentation results for our method and nnU-Net for Subjects A, B, and C. Each subplot shows the manual segmentation (first row in green), the segmentation results from RAovSeg (second row in red), and the segmentation results from nnU-Net (third row in yellow) for different subjects. Each column is for the same slices.

In this study, our experiments demonstrate that a customized deep learning method can generate promising results that surpass the performance of the baseline model, nnU-Net. By utilizing this dataset, further work can contribute to the improvement of absolute segmentation performance and its integration into a complete imaging pipeline for endometriosis screening and tracking.

Code availability

The software employed in this study for data generation or processing is described in the Methods section. No custom code was used to curate or validate the dataset itself. The image analysis tools developed for RAovSeg are now publicly accessible on GitHub at: https://github.com/xlianguth/RAovSeg.

References

World Health Organization. Endometriosis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/endometriosis (2023).

Zondervan, K. T. et al. Endometriosis. NEW ENGL J MED 382, 1244–1256, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1810764 (2020).

Shafrir, A. L. et al. Risk for and consequences of endometriosis: a critical epidemiologic review. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology 51, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.06.001 (2018).

Jha, P. et al. Endometriosis MRI lexicon: consensus statement from the society of abdominal radiology endometriosis disease-focused panel. Abdominal Radiology 45, 1552–1568, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-019-02291-x (2020).

Becker, C. M. et al. ESHRE guideline: endometriosis. Human reproduction open 2022, hoac009, https://doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoac009 (2022).

Bazot, M. et al. Deep pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging for diagnosis and prediction of extension of disease. Radiology 232, 379–389, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2322030762 (2004).

Deslandes, A., Parange, N., Childs, J. T., Osborne, B. & Bezak, E. Current status of transvaginal ultrasound accuracy in the diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis before surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 39, 1477–1490, https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15246 (2020).

Muzii, L. et al. Management of endometriomas, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1606279 (Seminars in reproductive medicine Ser. 35, Thieme Medical Publishers, 2017).

Nie, D., Wang, L., Gao, Y., Lian, J. & Shen, D. STRAINet: Spatially varying sTochastic residual AdversarIal networks for MRI pelvic organ segmentation. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 30, 1552–1564, https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2018.2870182 (2018).

Huang, S. et al. Integrating multiple MRI sequences for pelvic organs segmentation via the attention mechanism. Med. Phys. 48, 7930–7945, https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.15285 (2021).

Kurata, Y. et al. Automatic segmentation of the uterus on MRI using a convolutional neural network. Comput. Biol. Med. 114, 103438, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2019.103438 (2019).

Hodneland, E. et al. Automated segmentation of endometrial cancer on MR images using deep learning. Scientific reports 11, 179, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80068-9 (2021).

Podda, A. S. et al. Multi-scale deep learning ensemble for segmentation of endometriotic lesions. Neural Computing and Applications 36, 14895–14908, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-024-09828-2 (2024).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition (Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016).

Liu, Y., She, G. & Chen, S. Magnetic resonance image diagnosis of femoral head necrosis based on ResNet18 network. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 208, 106254, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106254 (2021).

Oktay, O. et al. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.03999, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1804.03999 (2018).

Lempart, M. et al. Pelvic U-Net: multi-label semantic segmentation of pelvic organs at risk for radiation therapy anal cancer patients using a deeply supervised shuffle attention convolutional neural network. Radiation Oncology 17, 114, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-022-02088-1 (2022).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (, 2023).

Ma, J. et al. Segment anything in medical images. Nature Communications 15, 654, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-44824-z (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Segment anything model for medical images? Med. Image Anal. 92, 103061, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2023.10306 (2024).

Isensee, F. et al. nnu-net revisited: A call for rigorous validation in 3d medical image segmentation (International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Springer, 2024).

Isensee, F., Jaeger, P. F., Kohl, S. A., Petersen, J. & Maier-Hein, K. H. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nature methods 18, 203–211, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01008-z (2021).

Liang, X. et al. UTHealth - Endometriosis MRI Dataset (UT-EndoMRI), https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15750762 (2024).

Zapf, A., Castell, S., Morawietz, L. & Karch, A. Measuring inter-rater reliability for nominal data–which coefficients and confidence intervals are appropriate? BMC medical research methodology 16, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0200-9 (2016).

De Swert, K. Calculating inter-coder reliability in media content analysis using Krippendorff’s Alpha. Center for Politics and Communication 15, 3 (2012).

Abraham, N. &Khan, N. M. A novel focal tversky loss function with improved attention u-net for lesion segmentation (2019 IEEE 16th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI 2019), IEEE, 2019).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Robert and Janice McNair Foundation. Xiaomin Liang is a CPRIT Predoctoral Fellow in the Biomedical Informatics, Genomics and Translational Cancer Research Training Program (BIGTCR) funded by Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT RP210045). We also want to thank Memorial Hermann Hospital System and Texas Children’s Hospital Pavilion for Women for their support. Dr. Sheth reports funding from the NIH (5R01N138765) as well as consulting fees for unrelated projects from Viz.AI, Penumbra, Medtronic, Route 92 and Perfuze.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. developed the methodology, created the figure, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript (methodology, visualization, writing-original-draft). L.G. and X.L. conceived the initial idea (conceptualization, investigation). X.L., L.A.R., K.K., H.D., C.M. created the labels for the dataset (data-curation). L.G., X.G., V.S.T. reviewed the data (validation). L.G., X.G., K.R., S.S., acquired funding to support these (funding-acquisition). L.G. supervised the processing (supervision, project administration). All authors contributed to the drafts and gave final approval for publication (writing-review-editing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, X., Alpuing Radilla, L.A., Khalaj, K. et al. A Multi-Modal Pelvic MRI Dataset for Deep Learning-Based Pelvic Organ Segmentation in Endometriosis. Sci Data 12, 1292 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05623-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05623-3