Abstract

This study introduces the first publicly available annotated intraoral image dataset for Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven dental caries detection, addressing the lack of available datasets. It comprises 6,313 images collected from individuals aged 10 to 24 years in Mithi, Sindh, Pakistan, with annotations created using LabelMe software. These annotations were meticulously verified by experienced dentists and converted into multiple formats, including YOLO (You Only Look Once), PASCAL VOC (Pattern Analysis, Statistical Modeling, and Computational Learning Visual Object Classes), COCO (Common Objects in Context) for compatibility with diverse AI models. The dataset features images captured from various intraoral views, both with and without cheek retractors, offering detailed representation of mixed and permanent dentitions. Five AI models (YOLOv5s, YOLOv8s, YOLOv11, SSD-MobileNet-v2, and Faster R-CNN) were trained and evaluated, with YOLOv8s achieving the best performance (mAP = 0.841 @ 0.5 IoU). This work advances AI-based dental diagnostics and sets a benchmark for caries detection. Limitations include using a single mobile device for imaging. Future work should explore primary dentition and diverse imaging tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & summary

The World Health Organization (WHO) expressed deep concern over the significant burden of oral diseases, including dental caries, which affects 3.5 billion people worldwide1. The prevalence of dental caries continues to increase, especially in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), particularly among children and adolescents2,3. This may be due to limited access to dental services, lack of awareness and negligence regarding oral hygiene measures.

Conventional diagnostic methods, such as visual examination and X-ray imaging, have long served as the cornerstone of caries detection in dentistry. However, these approaches are not always reproducible, as they rely on the clinician’s experience and judgment4. Although diagnostic studies have shown that trained dentists can generally achieve good intra- and inter-examiner reliability, there are repeated situations in daily practice where contradictory diagnoses are observed5. Factors such as lighting conditions, limited visibility, and variations in clinical settings can contribute to these inconsistencies6. As a result, there is an increasing demand for innovative solutions to enhance diagnostic accuracy and improve reproducibility. To address this challenge, the integration of AI in dental caries detection has shown significant advancements, leveraging Deep Learning (DL) and Machine Learning (ML) techniques7,8.

The success of AI models in accurately detecting dental caries depends heavily on the quality and quantity of the datasets9. A critical requirement is the availability of large-scale clinical and radiographic datasets. While radiographic datasets are widely accessible and well-studied, there is a significant gap in publicly available datasets of annotated intraoral images6,10,11,12. Studies such as Yoon et al. have utilized a dataset of over 24,000 intraoral images, each annotated with bounding boxes to mark carious regions13. A notable limitation is that this dataset is not open source, restricting its accessibility to the researchers. In contrast, another study reported a publicly available dataset of 718 intraoral images annotated for carious teeth highlighting the importance of well-annotated datasets14. However, the relatively small size of this dataset presents a limitation, as AI models typically require larger datasets to achieve robust and accurate performance. To address these concerns, this work aims to provide a comprehensive dataset of annotated intraoral images which has been made openly available on Zenodo15.

Methods

Ethical approval

The collection and curation of this dataset was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines set by the Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of The Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH). The images in this dataset were collected during a previously conducted study (ERC#2024-9433-29648)16. Written informed consent and assent was obtained from all participants in both English and local languages (Urdu and Sindhi) for the use and open sharing of their anonymized data. Assent was obtained from the participants under the age of 18 along with consent from their parents or legal guardians prior to data collection. To ensure privacy and confidentiality, all patient metadata was anonymized using a custom python code.

Data inclusion criteria

Adolescents (10–18 years) and young adults (19–24 years), both males and females.

Data exclusion criteria

-

1.

Images with suboptimal diagnostic quality, such as blurred images and those obscured by saliva or blood.

-

2.

Images with developmental dental anomalies, such as cleft lip/palate.

-

3.

Patients with limited mouth opening.

-

4.

Patient who did not give consent.

Data collection

Study setting

The data collection process was carried out in the government schools of Mithi, Sindh, Pakistan.

Mobile application for data collection

A mobile application was developed as part of the authors’ previous study16. Firebase cloud storage was integrated into the application, enabling a streamlined data pipeline for efficient image transfer from the data collection sites to AKUH. This pipeline begins with the images being captured and uploaded from the application to cloud storage. Subsequently, images were imported into the secure servers for annotations and model development at AKUH.

Training of the data collectors

Dentists underwent a comprehensive hands-on training session at AKUH prior to the data collection process. This included a detailed demonstration of the mobile application workflow to ensure its usability was adequately explained. The data collectors were also given hands-on training for capturing intraoral images with and without cheek retractors to ensure consistency.

The data collectors were instructed to obtain informed consent and assent followed by performing ultrasonic scaling of each participant. Images were to be captured using a Samsung Galaxy A23 (Android version 14.0) mobile device, from various angles of maxilla and mandible, including occlusal, frontal, and lateral views. Before capturing the images, the data collectors were instructed to clear the teeth, gingiva, buccal and lingual vestibules and floor of the mouth of visible saliva.

Pilot activity

To validate the robustness of the data collection process, a pilot activity was first conducted. This preliminary step aimed to test the feasibility of the process, identifying potential challenges, and ensuring consistency in capturing high-quality images. In the pilot phase a sample size of 101 participants was chosen to provide a representative subset of the target population resulting in 505 intraoral images in total taken only without a cheek retractor. The insights gained from this pilot phase were instrumental in refining the methodology before transitioning to the full data collection process.

Annotations

The intraoral images retained in the cloud storage were transferred to a HP Desktop Pro (G3 Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-9400, built-in Intel(R) UHD Graphics 630) and visually analyzed using a HP P19b G4 WXGA second-grade monitor display (1366 × 768)17. Two dentists (A.K and A.N), each with more than two years of experience, carried out the annotation process at AKUH, using the open-source tool LabelMe V5.4.1 (Massachusetts Institute of Technology - MIT, Cambridge, United States) (https://github.com/wkentaro/labelme). Before commencing the annotation process, these annotators received calibration training by a specialist dentist (N. A). The training focused on accurately identifying and labeling all carious teeth visible in the intraoral images received during pilot activity. The annotators used bounding boxes to define the height, width, and coordinates of the corners of each box surrounding a tooth with visible decay. Disagreements between the two annotators were resolved by a third dentist (N.A) ensuring the accuracy and consistency of annotations. Figure 1 illustrates the dataset curation pipeline, including data collection, filtering, and annotation.

Data records

The dataset15 consists of intraoral images in JPG format, annotated using LabelMe software. Each annotation file includes detailed information about the spatial positioning of teeth and cavities in the images. This data includes the coordinates of bounding boxes marking regions of interest and the location of decay, with ‘d’ and ‘D’ denoting primary and permanent tooth decay, respectively. The annotation files are saved in.json format, adhering to the standardized structure for LabelMe. The JSON annotation files were also converted into You Only Look Once (YOLO) (.txt), Pattern Analysis, Statistical Modeling, and Computational Learning Visual Object Classes (PASCAL VOC) (.xml), and Common Objects in Context (COCO) (.json) formats using Python, thereby making them available in various formats for future studies.

Technical validation

To ensure the reliability and quality of the dataset, a thorough validation process was conducted. First, to maintain consistency in image capture, the mobile application incorporates a built-in grid system, ensuring a uniform aspect ratio and standardized framing across all views. Images were taken with patients seated on a dental chair, and lighting conditions were standardized using the dental unit’s overhead light to ensure adequate illumination and minimize variability in image quality.

Second, all image and annotation files were reviewed for missing or corrupted data. Any files flagged during this process were rechecked and either corrected or removed. All patient-identifying information was thoroughly de-identified using a custom Python code. Annotation files were also verified for accuracy across all supported formats (YOLO, PASCAL VOC, and COCO), and bounding box coordinates and labels were checked to ensure compliance with the specifications of each format.

Third, to assess the consistency of annotations, inter-rater reliability was evaluated between the two annotators (A.K and A.N). Cohen’s Kappa coefficient, calculated on 10% of the total dataset (i.e, 631 out of 6,313 intraoral images), was found to be 0.89, indicating a high level of agreement. The specific images used for this assessment were included in the dataset. This rigorous validation ensures that the dataset is suitable for training and benchmarking DL models for dental caries detection.

Data description

Root folder

The dataset is available on the Zenodo repository and is organized into three main folders: images, annotations and benchmark as shown in Fig. 215. The ‘images’ folder has three subfolders: ‘pilot activity images’, images taken with a ‘cheek retractor (W/R)’ and another for images taken ‘without a cheek retractor (W/O-R)’. The W/R and W/O-R subfolders are further divided into folders based on different views (maxillary occlusal, mandibular occlusal, left lateral, right lateral and frontal), and labeled accordingly. The annotations folder is divided into four subfolders for different annotation formats: LabelMe, YOLO, PASCAL VOC, and COCO. Each format folder, except for COCO, contains subfolders labeled as ‘Pilot’, ‘WR’ and ‘W/O-R’. This is because, in all formats except COCO, each image has a corresponding label, whereas in the COCO format, an entire folder of images is assigned a single label. Additionally, these subfolders are further organized by views.

Benchmark folder

The benchmark folder as shown in Fig. 3 is organized into three subfolders: train, test, and valid. Each subfolder is further divided into the following categories: Images, YOLO, PASCAL VOC, LabelMe, and COCO. These categories contain the images and their corresponding annotation files, ensuring compatibility with various annotation formats. This clear and structured organization makes the dataset easy to navigate and use for research and training AI models.

Image views

A total of ten images were captured for each patient, five with cheek retractors and five without them as shown in Fig. 4. The first set of ‘images’ folder, labeled as ‘W/R’ in the dataset indicates the use of cheek retractors. While images in the second folder, labeled as ‘W/O-R’ in the dataset were captured using a tongue depressor only. Each set includes five images per patient in the following views:

-

1.

An occlusal view of the maxillary arch (first image).

-

2.

An occlusal view of the mandibular arch (second image), taken after posterior retraction of the tongue.

-

3.

Buccal view of the left lateral teeth (third image).

-

4.

Buccal view of the right lateral teeth (fourth image).

-

5.

A frontal view image with the dentition in habitual occlusion (fifth image).

Data results

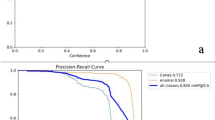

Five models, YOLOv5s, YOLOv8s, YOLOv11, SSD-MobileNet-v2-FPNLite-320, and Faster R-CNN, were trained and evaluated on the curated dataset. The dataset comprised of 6,313 images which was split into 5,050 for training, 631 for validation, and 631 for testing. Default data augmentation techniques were applied to enhance generalizability, and all models were trained using default parameters to ensure a fair comparison. The specifications of the trained models are presented in Table 1.

Based on the results of the descriptive analysis, YOLOv8s exhibited superior performance across all models, achieving the highest values in key evaluation metrics such as precision, recall and mean Average Precision (mAP). This establishes it as the most suitable model for tasks demanding high accuracy and recall. YOLOv5s offers a practical alternative in scenarios where shorter training times are prioritized. While YOLOv11 is robust, it required more training epochs to approach the performance level of YOLOv8s.

Limitations

A major limitation of this dataset is the absence of annotations for dental fluorosis, despite its high prevalence in the region of data collection. This omission was due to the primary focus of the study on dental caries and the inherent difficulty in distinguishing fluorosis from non-cavitated carious lesions using only intraoral images. The visual similarity between the two conditions, particularly in 2D images without supporting clinical context, may lead to mislabeling or misinterpretation. Future datasets should incorporate separate annotations for fluorosis, ideally supported by clinical examination to enable accurate differentiation. Another limitation of this dataset is that it comprises images captured exclusively using a single type of mobile phone camera, which limits the generalizability of the image quality. Furthermore, the dataset excludes individuals under the age of 10, limiting its applicability for detecting caries in children, particularly in primary dentition. Future work should focus on examining caries in primary dentition to address this gap.

Data availability

Code availability

Custom Python codes were developed for anonymizing patient data and model training. These codes were intended for internal use only and are not publicly available.

References

Kassebaum, N. J., Bernabe, E., Dahiya, M., Bhandari, B., & Murray, C. J. L. Global burden of untreated caries: A systematic analysis of the global burden of diseases. Journal of Dental Research (2017).

Noor Uddin, A. et al. Applications of AI-based deep learning models for detecting dental caries on intraoral images–a systematic review. Evidence-Based Dentistry, 1-8 (2024).

Ntovas, P., Loubrinis, N., Maniatakos, P. & Rahiotis, C. Evaluation of dental explorer and visual inspection for the detection of residual caries among Greek dentists. Journal of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics 21, 311–318 (2018).

Litzenburger, F. et al. Inter-and intraexaminer reliability of bitewing radiography and near-infrared light transillumination for proximal caries detection and assessment. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology 47, 20170292 (2018).

Lee, S. et al. Deep learning for early dental caries detection in bitewing radiographs. Scientific reports 11, 16807 (2021).

Adnan, N., Umer, F., & Malik, S. Multi-model deep learning approach for segmentation of teeth and periapical lesions on pantomographs… Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology (2024).

Jiang, X., & Zhang, Y. Application of artificial intelligence in dental caries detection: A review. Journal of Healthcare Engineering (2021).

Ding, H. et al. Artificial intelligence in dentistry—A review. Frontiers in Dental Medicine 4, 1085251 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Children’s dental panoramic radiographs dataset for caries segmentation and dental disease detection. Scientific Data 10, 380 (2023).

Pérez de Frutos, J. et al. AI-Dentify: deep learning for proximal caries detection on bitewing x-ray-HUNT4 Oral Health Study. BMC Oral Health 24, 344 (2024).

Srivastava, M. M., Kumar, P., Pradhan, L. & Varadarajan, S. Detection of tooth caries in bitewing radiographs using deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.07312 (2017).

Yoon, K., Jeong, H.-M., Kim, J.-W., Park, J.-H. & Choi, J. AI-based dental caries and tooth number detection in intraoral photos: Model development and performance evaluation. Journal of Dentistry 141, 104821 (2024).

Frenkel, E. et al. Caries Detection and Classification in Photographs Using an Artificial Intelligence-Based Model—An External Validation Study. Diagnostics 14, 2281 (2024).

Annotated intraoral image datset for dental caries detection. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14827784 (2025).

Adnan, N. et al. Developing an AI-based application for caries index detection on intraoral photographs (2024).

Hameed, M. H., Umer, F., Khan, F. R., Pirani, S. & Yusuf, M. Assessment of the diagnostic quality of the digital display monitors at the dental clinics of a university hospital. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 11, 83–86 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the data collectors (Sujeet Lohana, Bhagshali) for their invaluable contributions, which were helpful in obtaining this extensive dataset. The curation of this dataset was made possible thanks to a grant from the FDI World Dental Development Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.F.A.: Writing – Original Draft, Data Analysis, M.H.G.: Data Analysis A.K.: Writing – Original Draft, A.N.: Writing – Original Draft, N.A.: Writing – Original Draft, Data Analysis, A.L.: Writing – Original Draft, Figures, F.U.: Conceptualization, Study Design, Writing – Original Draft, Data Analysis, Final Approval of Manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Faizan Ahmed, S.M., Ghori, M.H., Khalid, A. et al. Annotated intraoral image dataset for dental caries detection. Sci Data 12, 1297 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05647-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05647-9