Abstract

Gastric cancer, a significant global health concern, exhibits high morbidity and mortality, especially in advanced stages. Timely diagnosis and intervention are crucial for improving patient outcomes, with Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD) playing a pivotal role in precise, minimally invasive early-stage treatments. Despite its importance, challenges include significant interobserver variability among pathologists and the intensive labor required for detailed pathological analysis of ESD specimens impede optimal outcomes. Artificial Intelligence (AI) offers promising solutions to these challenges, yet its advancement is limited by the scarcity of comprehensive, annotated pathological datasets. In this paper, we curate a fully annotated pathology slide dataset for ESD specimen examination. This dataset not only poses a challenging task for the computational pathology field but also enables precise detection of precancerous stages and accurate quantification of lesion distribution in patients with early-stage gastric lesions. Furthermore, it enhances the correlation between endoscopic findings and pathological interpretations, thereby advancing precision medicine strategies in the prevention and treatment of early gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Globally, gastric cancer remains a major cause of cancer-related deaths, accounting for approximately 1 million new cases and 768,793 deaths in 20201,2,3,4. The high fatality rates are largely attributed to late-stage diagnoses. The five-year survival rate for patients diagnosed at an early stage is over 90%5, whereas it drops to 40% for those diagnosed at a late stage3,4. Early diagnostic measures, particularly endoscopic screening6, play a crucial role. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD) is instrumental in treating early-stage gastric cancer, significantly improving survival rates7,8. ESD is instrumental in treating early-stage gastric cancer, achieving survival rates comparable to surgical intervention for appropriately selected cases. ESD offers significant advantages: it is minimally invasive, associated with lower complication rates, cost-effective, less painful, and allows for organ preservation, ultimately enhancing the patient’s quality of life.

Despite the significant advancements brought by ESD, the pathology examination remains the gold standard, requiring pathologists to perform detailed quantitative diagnoses on tissues resected in ESD8. However, two significant challenges beset this process. Firstly, there is considerable interobserver variability among pathologists when diagnosing precancerous lesions9,10, which can lead to inconsistent results and potentially delay the initiation of treatment. Secondly, and most critically, the requirement for pathologists to create lesion distribution maps for precise quantitative assessments based on pathological slides is extremely time-consuming and often impractical in routine diagnostic workflows.

Lesion distribution maps, in clinical practice, correspond to the manual reconstruction of resected specimens, where serial tissue sections are aligned to restore the lesion’s original location and extent11. This labor-intensive process is commonly used to visualize the spatial distribution of tumors and other relevant histological components within the resected tissue. Automating the creation of lesion distribution maps could significantly benefit pathologists, endoscopists, and patients, each in their own way. For pathologists, it enhances their capacity for detailed quantitative diagnostics12, boosting their confidence in managing complex cases13. For patients, precise quantification of lesion sizes by pathologists is crucially influential in the effectiveness of treatments and the development of subsequent therapeutic strategies8,14. Moreover, the combination of advances in chromoendoscopy and high-resolution endoscopic equipment enables more detailed observations of pathological features15. It allows endoscopists to align pathological lesion distribution maps with endoscopic images. Such alignment could enhance the accuracy of morphological analyses in early gastric cancer, crucially aiding in the precise identification and optimal resection of lesions during ESD procedures13,16,17,18.

Recent advancements in computational pathology (CPath), particularly deep learning models, have introduced transformative potentials in pathological image analysis and diagnosis19,20. While current CPath models focus on coarse-grained diagnostics, such as differentiating between benign and malignant tumors and subtyping cancers21, their application in gastric cancer has shown promising results. Numerous studies have demonstrated high accuracy in distinguishing benign from malignant gastric tumors22,23, and in subtyping gastric cancer according to the Lauren classification system24,25. Additionally, deep learning models have been applied to detect Helicobacter pylori26, assess the degree of intestinal metaplasia27, and identify dysplasia28. However, these studies are isolated and preliminary, and as a comprehensive, targeted investigation into gastric cancer diagnostic applications, they are hindered by the lack of fully annotated datasets. Although Hu et al.29 released a large dataset containing 245,196 histopathological patches of gastric cancer. This dataset is limited to binary annotations distinguishing only between normal and tumor tissues, without detailed annotations for specific histological phenotypes, that are crucial for thoroughly examining gastric precancerous and cancerous specimens.

Therefore, to assist researchers in CPath with developing methods to track and quantify the pathological progression from Helicobacter pylori infection to gastric carcinoma30, we present a dataset named HiESD, consisting of histopathology images with detailed annotation of ESD specimens. This dataset comprises 308 de-identified tissue samples derived from 104 H&E stained digital slides, meticulously annotated into 10 distinct categories at the region level, enabling detailed and precise analysis at both the slide and region levels.

The potential applications of this dataset are listed as follows. Firstly, it could enhance diagnostic accuracy by enabling AI-driven models to reconstruct lesion distribution maps efficiently. This improvement fosters better alignment between endoscopic findings and pathological interpretations, optimizing diagnostic processes. Secondly, the dataset facilitates the precise detection of precancerous gastric changes, reinforcing early gastric cancer prevention strategies and ultimately enhancing patient outcomes. Lastly, it supports detailed spatial histomorphological analysis, offering critical insights into the spatiotemporal development of gastric cancer. The ESD data serves as a representative model for early tumor pathology diagnosis AI, as it generally encompasses characteristics of various stages of tumor development, including atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, and carcinoma. This analysis could lead to breakthroughs in understanding and treating this complex disease.

Methods

Research approval

The HiESD dataset was collected from the Main Hospital at the First Affiliated Hospital (FAH) of Xi’an Jiaotong University (XJTU). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the FAH of XJTU (IRB Approval No. XJTU1AF2024LSYY-149), which granted a formal waiver of informed consent because the study involved retrospective analysis of anonymized archival data, posed minimal risk to participants, and obtaining individual consent was impracticable due to the large-scale and de-identified nature of the dataset. Additionally, we collected two external test cohorts from the East Hospital of the FAH of XJTU and the Shaanxi Provincial Cancer Hospital, with respective approvals from their IRBs (IRB Approval Nos. XJTU1AF2024LSYY-149 and 2023-161), under similar waivers for the same reasons. All specimens were retrieved from the histopathological archives by the authors (CB.W. and CX.D.). To ensure patient privacy, all collected data were de-identified and stripped of all personal health information and identifiable markers.

Scanning equipment

Whole Slide Images (WSIs) of early gastric cancer specimens from the Main and the East Hospitals of FAH of XJTU were obtained using digital scanners (specifically KFBIO-005 and KF-SCAN-BS from Jiangfeng Biology) with a 40 × objective lens, producing images at a resolution of 0.25 μm/pixel. The WSIs collected from Shaanxi Provincial Cancer Hospital were acquired using a Hamamatsu scanner (S210 C13239-01) with a 40 × objective lens, yielding a resolution of 0.23 μm/pixel. The average pixel dimensions of the WSIs collected in this study were 54342 × 41048, with physical dimensions of 27.43 × 20.66 mm.

Specimen selection and preparation

Patients suspected of early gastric cancer clinically underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) performed by gastroenterologists. Tissue specimens were fixed, sampled, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and subjected to H&E staining according to the standard protocol for ESD specimens in Japan8. The HiESD dataset comprises 104 ESD slides from 44 patients. Also, we collected 155 slides of 20 patients from two different medical institutions as the external test cohorts, including 69 slides from the East Hospital of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University and 86 slides from the Shaanxi Provincial Cancer Hospital. The statistical details of different cohorts are shown in Table 1.

Statistical overview of the HiESD dataset and two external test cohorts. “Inhouse” refers to the HiESD dataset, which has been made publicly available for research purposes. In contrast, the “External” test cohorts are privately held and used exclusively for external validation and have not been made publicly accessible.

Considering the different sampling protocols across medical institutions, it is common to encounter instances where multiple tissue strips are mounted on a single slide. We treated each continuous tissue strip as a distinct specimen. In total, the HiESD dataset comprises 308 tissue specimens. Moreover, the selection of patients was random, and only slides with acceptable quality were included. Two pathologists with more than ten years of experience reviewed all digital slides, and slides exhibiting noticeable issues such as significant variations in color brightness, background color, or focus were rescanned.

WSI annotation

In this study, the OpenHi digital pathology annotation platform was utilized for dataset annotation31. Pathologists annotated WSIs using the iPad Pro (2022) equipped with a second-generation stylus pen. They circled histotypes with various tissue structures at appropriate magnification levels. The annotation categories included normal glands, chronic gastritis, lymphoid follicles indicative of Helicobacter pylori infection, precancerous lesions (i.e., chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia), and different cancer subtypes.

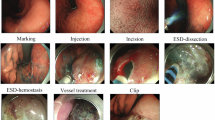

Specific annotation standards were established on morphological characteristics (as shown in Fig. 1) and definitions of different tissue categories (as shown in Table 2)14. Our annotation approach was meticulously designed to preserve the spatial structural features of tumor tissues as comprehensively as possible. For example, in annotating papillary adenocarcinoma, we circled both the distinctive papillary structures and the adjacent flat areas to capture the full tissue context. In contrast, our method for annotating chronic atrophic gastritis involved full-layer annotation highlighting the uneven glandular distribution within the lamina propria. Additionally, due to the strong association between lymphoid follicles and Helicobacter pylori infection32, these follicles were annotated separately, facilitating further detailed study.

WSI annotation standards and classification task instructions for the HiESD dataset: The first classification task, named “ESD Histotype Classification,” is represented by five black boxes, each denoting a category: tumors, intestinal metaplasia, normal mucosa and inflammation, lymphoid nodules, and other tissues. The second classification task, “ESD Malignant Tumor Subtyping,” categorizes tumors based on morphology into three sub-categories: papillary adenocarcinoma (pap), well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma (tub1), and moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma (tub2). The third classification task, “Incomplete Intestinal Metaplasia Detection,” divides intestinal metaplasia into two categories: complete intestinal metaplasia (C-Intestine) with mild atypia, and incomplete intestinal metaplasia (IC-Intestine) with moderate or higher atypia. Unannotated regions, shown in the upper left corner of the display, may contain other histological features but are not within the scope of interest for this dataset.

Furthermore, intestinal metaplasia is a key morphological feature of precancerous lesions. Complete intestinal metaplasia in the gastric mucosa is characterized by the presence of goblet cells and absorptive cells with brush borders. Conversely, incomplete intestinal metaplasia features goblet cells alongside non-absorptive columnar cells33,34. Under H&E staining, brush borders and goblet cells are readily identifiable morphological features. Given their clinical significance in assessing the presence or absence of dysplasia for prognosis, we annotated glands in both scenarios. The grading criteria for dysplasia in our annotations adhere to the Japanese standard14, chosen for its strong alignment with the endoscopic morphology typical of Japanese early cancer classification standards35. According to these annotation standards, our dataset categorizes high-grade dysplasia as “tumors”, low-grade dysplasia and incomplete intestinal metaplasia are grouped into “IC-Intestine”, and glands with brush borders and insignificant dysplasia are classified as the “C-Intestine”. Due to the inherent subjectivity of visual assessments in determining quantifiable indicators, this study does not annotate the degree of chronic inflammation, atrophy, or intestinal metaplasia.

To ensure the accuracy of the WSI annotation, two specialist pathologists (CB.W and CX.D) with expertise in early gastrointestinal cancer jointly conducted the annotation tasks during online meetings. Considering the substantial workload involved in annotating the dataset, we scheduled intermittent breaks of one week every month to maintain both the efficiency and accuracy of the pathologists’ work. We consulted expert gastroenterologists with senior professional titles (C.W) for areas subject to diagnostic disagreements to review and determine the final classification.

Data preprocessing

For each WSI, individual tissue strips were defined as connected regions and treated as separate data samples. For the classification task, we tessellated each tissue strip into multiple non-overlapping patches of size 1024 × 1024 pixels at the highest magnification level (40 ×). To eliminate irrelevant regions, we discarded patches where the background occupied more than 75% of the area, resulting in a total of 133,636 valid patches. In addition to the patch-level classification task, we also conducted pixel-level tissue segmentation experiments. For segmentation, we applied a sliding window operation at 10 × magnification to better preserve tissue-level contextual information. Specifically, we extracted 1024 × 1024 pixel patches with a stride of 1024 pixels.

Assigning labels to patches

Patch labels were assigned based on the color-coded annotation masks of each WSI, where each unique RGB value corresponds to a specific tissue category. For each patch, we identified its corresponding region on the annotation mask, calculated the proportion of pixels belonging to each color category, and assigned the patch the label corresponding to the dominant color (i.e., the one with the highest proportion). This strategy was used to generate categorical labels for all classification patches. For the segmentation task, the same color annotation masks were converted into pixel-level categorical labels, enabling supervision at the pixel level for training and evaluating tissue segmentation models.

Data Records

Data information

The HiESD dataset has been uploaded to Figshare and is freely accessible36. It comprises 104 ESD-resected gastric mucosal WSIs, containing 308 tissue samples. Table 2 details the number and proportion of extracted patches (as described in “Methods”) for each histotype that we have annotated across various tissue strips. In ESD surgery, to ensure complete removal of the lesion, surrounding tissue is also excised, which includes non-cancerous areas. This comprehensive annotation approach allows the HiESD dataset to accurately represent the proportional distribution of various histotypes in actual ESD specimens.

The following data are provided: (1) original whole slide image (WSI) files from the HiESD dataset (.svs); (2) quality assessment masks for all WSIs (.png); (3) annotations and thumbnails of WSIs downsampled by a factor of 64 (.png), with corresponding annotation files also provided in XML format and (4) connected component images (.png) corresponding to each tissue strip. WSI files (.svs) are compatible with open-source tools, including the Python package OpenSlide37 for programmatic access and the software QuPath38 for interactive visualization and analysis. This allows users to efficiently view, process, and analyze whole slide images at multiple resolutions. For each tissue strip, we generated a connected component to pinpoint its location within the original WSI. In total, 308 connected component images were produced and are available in PNG format. The tissue strips are sequentially numbered from 001 to 308, with the WSIs ranging from “slide_1” to “slide_104”. To simplify data management, folders for tissue strips from the same WSI are grouped together under the corresponding WSI folder. Additionally, a standard CSV file provides detailed mappings between tissue strip numbers, slide numbers, SVS files, annotation files, and connected component files.

Patient cohort

The HiESD dataset consists of 44 patients, comprising 28 males and 16 females. The patients ranged in age from 30 to 80 years, with a mean age of 60.4 years. The anatomical distribution and location of the lesions, along with the pathological diagnosis of patients, are presented in Fig. 2. Further detailed patient data are listed in Table (Supplementary) 1.

Technical Validation

Data quality assessment

To comprehensively assess the quality of all slides in the dataset, we employed GrandQC39, a recently proposed state-of-the-art quality control tool for digital pathology. This tool enables high-precision artifact detection on WSIs, identifying common issues such as air bubbles, slide edges, out-of-focus regions, pen markings, tissue folds, foreign objects, and dark spots. Using GrandQC, we quantified the proportion of each slide affected by these artifact categories, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Among the 104 slides, only five slides exhibited a relatively high proportion of out-of-focus artifacts and pen markings. However, these artifacts were still limited to only 10–20% of the slide area, and most were located in non-annotated regions, thus having minimal impact on the usability and overall quality of the dataset. Quality assessment masks are also provided for all slides, allowing users to exclude artifact-affected tissue regions in practical applications.

Baseline models

To assess the dataset’s usability, we trained and evaluated three baseline models (i.e., ResNet-50, CONCH, and UNI) across all three patch-level classification tasks. In addition, we implemented a ResUNet model as a baseline for the pixel-level segmentation task of ESD histotype classification. (1) ResNet-5040: This model employs residual modules to extract complex image features and pre-trained on ImageNet dataset, offering strong expressive power that is extensively applied in pathology image analysis. (2) CONCH41: CONCH is a visual language based model for histopathology. It is pre-trained on the largest visual language dataset dedicated to histopathology and has good representation capabilities for pathological images. (3) UNI42: UNI advances unsupervised representation learning at scale in computational pathology, which can be applied to a variety of diagnostic challenges and clinical workflows in pathology. (4) ResUNet43: In order to verify the applicability of the dataset in pixel-level segmentation tasks, we introduced ResUNet for evaluation, using ResNet-5040 as the backbone. ResUNet is a deep learning model that combines the residual network (ResNet) and U-Net architectures, aiming to use the deep feature extraction capabilities of ResNet and the multi-scale information fusion capabilities of U-Net to achieve accurate and robust image segmentation results.

The dataset was partitioned at the patient level using a five-fold cross-validation strategy. For each fold, baseline models were fine-tuned on the training set comprising four folds and evaluated on the remaining fold, enabling robust assessment of performance across both classification and segmentation tasks. During training, we applied image augmentation techniques such as color space transformations and flipping to enhance the robustness of the model. The Adam optimizer was used, with the maximum learning rate set to 1e-2 and the minimum learning rate automatically adjusted to 1% of the maximum. The batch size was set to 32. All baseline models were trained for 60 epochs. For ResNet-50, all network parameters were optimized during training. As the backbones of UNI and CONCH were pre-trained on large-scale pathology image datasets, only the parameters of the last fully connected layers were fine-tuned. We evaluated the trained patch-level classification models using four metrics: accuracy, recall, F1-score, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC). For pixel-level segmentation models, we used accuracy, recall, and Dice score as evaluation metrics. Additionally, we reported macro-averaged scores for all classification and segmentation tasks.

Patch-level classification

The internal cross-validation results for three classification tasks are illustrated in Fig. 4. The AUROC scores for all baseline models are as follows: 0.91 to 0.94 for ESD histotype classification, 0.82 to 0.88 for ESD malignant tumor subtyping, and 0.88 to 0.90 for incomplete intestinal metaplasia detection. For both ESD histotype classification and incomplete intestinal metaplasia detection, the baseline models achieved precision, recall, and F1-scores around 0.8. However, for ESD malignant tumor subtyping, these performance metrics drop to approximately 0.65. This discrepancy is likely due to the imbalanced data distribution and the inherent difficulty in distinguishing between the categories. These results indicate that the fine-grained classification tasks are more challenging for the current baseline models compared to the coarse-grained task, with tumor subtyping proving to be particularly more difficult than incomplete intestinal metaplasia detection. Additionally, the classification performance for lymphoid nodules is significantly lower, which can be attributed to the limited data available for these categories.

As foundation models pre-trained on large-scale pathology image datasets, UNI and CONCH demonstrated a 3–4% advantage in AUC scores over the ImageNet-pretrained ResNet-50 on the coarse-grained ESD Histotype Classification task. However, their performance did not show clear benefits in the two fine-grained tasks. In the ESD Malignant Tumor Subtyping task, both models underperformed compared to ResNet-50. These results suggest that existing foundation models in the pathology domain may lack sufficient feature discrimination capability for subtle histological distinctions. One possible reason is that the backbone parameters were frozen during fine-tuning, limiting model adaptability to task-specific features. Overall, these findings highlight the challenges of fine-grained classification at the patch level and raise questions about how to best leverage foundation models for such tasks. The ESD dataset provides a valuable benchmark in this direction.

External validation

To evaluate the generalization ability of the baseline models trained on the HiESD dataset, we tested them on two external cohorts comprising WSIs of ESD specimens, as detailed in Table 1. As shown in Fig. 5, all three models exhibited a performance decline on the external cohorts, likely due to variations in tissue sectioning, scanning, and staining protocols across different hospitals. The AUROC scores ranged from 0.89 to 0.95, 0.70 to 0.89, and 0.76 to 0.91 for the three tasks, respectively. For the ESD Histotype Classification task, UNI and CONCH showed only a modest drop of 1–2%, while the two fine-grained tasks experienced more noticeable decreases. Nevertheless, the performance remained within an acceptable range, demonstrating the robustness and generalizability of the HiESD dataset across institutions and highlighting its value as a benchmark for real-world computational pathology applications.

Lesion distribution map

We visualized the baseline model (UNI) predictions on three patch-level classification tasks, as illustrated in Fig. 6. While the lesion distribution maps generated from patch-level predictions are coarser than pixel-level segmentation, they still offer clinically meaningful localization of key histological features at the WSI scale. The visualized results indicate that models trained on the HiESD dataset exhibit strong predictive performance across multiple histopathological tasks, further supporting the high quality of both slide images and annotations in the ESD dataset.

Pixel-level segmentation

Following the settings of the ESD histotype classification task, each pixel was classified into one of five categories: tumor, normal or inflamed tissue, lymphoid nodule, intestinal metaplasia, and other tissue. We evaluated segmentation performance using a ResUNet baseline model. The internal cross-validation results are as follows: for tumors, the Dice score and Recall were 0.52 ± 0.03 and 0.70 ± 0.06, respectively; for normal or inflamed tissues, the Dice score and Recall were 0.65 ± 0.03 and 0.73 ± 0.05; for lymphoid nodules, 0.50 ± 0.08 and 0.73 ± 0.07; and for intestinal metaplasia, 0.32 ± 0.04 and 0.43 ± 0.07. The segmentation performance for intestinal metaplasia was relatively poor, primarily due to its low prevalence in the dataset, resulting in a class imbalance that limited the model’s learning effectiveness.

Usage Notes

The original WSIs in the ESD dataset are provided in SVS (.svs) format, which can be accessed using the OpenSlide package in Python. For various downstream tasks, users may tessellate the WSIs into patches of a specified size and record the coordinates of each patch. These coordinates can then be used to identify corresponding regions in the annotation masks, thereby determining the class label for each patch. Additionally, each tissue strip is associated with a connected component image, enabling users to determine which tissue strip a given patch originates from based on its location coordinates.

It is important to note that the pixel-level annotations in this dataset were created for research purposes and are not intended for highly precise boundary-level segmentation. In many cases, glandular structures were annotated collectively (particularly cancerous glands) rather than with detailed contours of individual glands. This introduces a level of spatial imprecision that may affect the performance of pixel-level segmentation models. Therefore, we recommend that the dataset be primarily used for patch-level classification tasks, for which the existing annotations are more appropriate in terms of granularity and practical diagnostic relevance.

Code availability

All codes for data processing and validation experiments are available at https://github.com/JSGe-AI/HiESD. This includes the code for tessellating patches, assigning labels, and the previously described data preprocessing steps. Additionally, the repository contains the training codes for the four baseline models along with their trained weights on the HiESD dataset.

All data files except for the original whole slide images, such as annotation masks, tissue strip masks, and slide thumbnails, can be accessed at https://huggingface.co/datasets/JSGe-AI/HiESD.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 71, 209–249, https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Chiarello, M. M. et al. Early gastric cancer: A challenge in western countries. World Journal of Gastroenterology 28, 693, https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i7.693 (2022).

Yan, X. et al. Stomach cancer burden in china: Epidemiology and prevention. Chinese journal of cancer research 35, 81, https://doi.org/10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2023.02.01 (2023).

Thrift, A. P., Wenker, T. N. & El-Serag, H. B. Global burden of gastric cancer: Epidemiological trends, risk factors, screening and prevention. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 20, 338–349, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00747-0 (2023).

Onodera, H. et al. Surgical outcome of 483 patients with early gastric cancer: Prognosis, postoperative morbidity and mortality, and gastric remnant cancer. Hepato-gastroenterology 51, 82–85 PMID:15011835 (2004).

Namasivayam, V. Endoscopic screening and surveillance for gastric cancer: Challenges and opportunities. Faculty Reviews 12, https://doi.org/10.12703/r/12-17 (2023).

Forbes, N. et al. American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy guideline on endoscopic submucosal dissection for the management of early esophageal and gastric cancers: Summary and recommendations. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 98, 271–284, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2023.03.015 (2023).

Ono, H. et al. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Digestive Endoscopy 33, 4–20, https://doi.org/10.1111/den.13883 (2021).

Lauwers, G. & Riddell, R. Gastric epithelial dysplasia. Gut 45, 784–784, https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.45.5.784 (1999).

Leja, M. et al. Interobserver variation in assessment of gastric premalignant lesions: Higher agreement for intestinal metaplasia than for atrophy. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 25, 694–699, https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835e3397 (2013).

Dinis-Ribeiro, M. et al. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and early neoplasia of the stomach (MAPS III): European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE), european helicobacter and microbiota study group (EHMSG) and european society of pathology (ESP) guideline update 2025. Endoscopy, https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2529-5025 (2025).

Xiao, Y. et al. Artificial intelligence assisted topographic mapping system for endoscopic submucosal dissection specimens. Frontiers in Medicine 9, 822731, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.822731 (2022).

Niv, Y. Pathologists and gastroenterologists. Journal of clinical pathology 56, 241–242, https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.56.4.241 (2003).

jp, J. G. C. A. jgca@ koto. kpu-m. ac. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd english edition. Gastric cancer 14, 101–112, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0041-5 (2011).

Zhai, W. Technical advances in gastrointestinal endoscopy in the diagnosis of early gastric cancer. International Journal of Public Health and Medical Research 1, 11–17, https://doi.org/10.62051/ijphmr.v1n2.02 (2024).

Di, L. et al. Multi-disciplinary team for early gastric cancer diagnosis improves the detection rate of early gastric cancer. BMC gastroenterology 17, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-017-0711-9 (2017).

Lim, J. H. et al. Correlation between endoscopic and histological diagnoses of gastric intestinal metaplasia. Gut and liver 7, 41, https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl.2013.7.1.41 (2013).

Eshmuratov, A. et al. The correlation of endoscopic and histological diagnosis of gastric atrophy. Digestive diseases and sciences 55, 1364–1375, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-009-0891-4 (2010).

Gao, Z. et al. A semi-supervised multi-task learning framework for cancer classification with weak annotation in whole-slide images. Medical Image Analysis 83, 102652, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2022.102652 (2023).

Song, A. H. et al. Artificial intelligence for digital and computational pathology. Nature Reviews Bioengineering 1, 930–949, https://doi.org/10.1038/s44222-023-00096-8 (2023).

Choi, S. & Kim, S. Artificial intelligence in the pathology of gastric cancer. Journal of Gastric Cancer 23, 410, https://doi.org/10.5230/jgc.2023.23.e25 (2023).

Ma, B. et al. Artificial intelligence-based multiclass classification of benign or malignant mucosal lesions of the stomach. Frontiers in Pharmacology 11, 572372, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.572372 (2020).

Song, Z. et al. Clinically applicable histopathological diagnosis system for gastric cancer detection using deep learning. Nature communications 11, 4294, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18147-8 (2020).

Kanavati, F. & Tsuneki, M. A deep learning model for gastric diffuse-type adenocarcinoma classification in whole slide images. Scientific Reports 11, 20486, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99940-3 (2021).

Gao, Z. et al. Accurate spatial quantification in computational pathology with multiple instance learning. MedRxiv 2024–04, https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.25.24306364 (2024).

Goncalves, W. G. E. et al. DeepHP: A new gastric mucosa histopathology dataset for helicobacter pylori infection diagnosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, 14581, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314581 (2022).

Iwaya, M. et al. Artificial intelligence for evaluating the risk of gastric cancer: Reliable detection and scoring of intestinal metaplasia with deep learning algorithms. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 98, 925–933, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2023.06.056 (2023).

Park, J. et al. A prospective validation and observer performance study of a deep learning algorithm for pathologic diagnosis of gastric tumors in endoscopic biopsies. Clinical Cancer Research 27, 719–728, https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3159 (2021).

Hu, W. et al. GasHisSDB: A new gastric histopathology image dataset for computer aided diagnosis of gastric cancer. Computers in Biology and Medicine 142, 105207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.105207 (2022).

Vincze, Á. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment in gastric cancer: Current evidence and new perspectives. Frontiers in Surgery 10, 1122454, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2023.1122454 (2023).

Puttapirat, P. et al. OpenHI-an open source framework for annotating histopathological image. in 2018 IEEE international conference on bioinformatics and biomedicine (BIBM) 1076–1082, https://doi.org/10.1109/BIBM.2018.8621393 (IEEE, 2018).

Dwivedi, M., Misra, S. P. & Misra, V. Nodular gastritis in adults: Clinical features, endoscopic appearance, histopathological features, and response to therapy. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology 23, 943–947, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05044.x (2008).

Livzan, M. A., Mozgovoi, S. I., Gaus, O. V., Shimanskaya, A. G. & Kononov, A. V. Histopathological evaluation of gastric mucosal atrophy for predicting gastric cancer risk: Problems and solutions. Diagnostics 13, 2478, https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13152478 (2023).

Shah, S. C., Gawron, A. J., Mustafa, R. A. & Piazuelo, M. B. Histologic subtyping of gastric intestinal metaplasia: Overview and considerations for clinical practice. Gastroenterology 158, 745–750, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.004 (2020).

Kawamura, M. et al. Endoscopic and histological risk stratification for gastric cancer using gastric intestinal metaplasia. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.16617 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. A fully annotated pathology slide. dataset for early gastric cancer and precancerous lesions. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28919840 (2025).

Goode, A., Gilbert, B., Harkes, J., Jukic, D. & Satyanarayanan, M. OpenSlide: A vendor-neutral software foundation for digital pathology. Journal of pathology informatics 4, 27, https://doi.org/10.4103/2153-3539.119005 (2013).

Bankhead, P. et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Scientific reports 7, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17204-5 (2017).

Weng, Z. et al. GrandQC: A comprehensive solution to quality control problem in digital pathology. Nature Communications 15, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54769-y (2024).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. IEEE, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 (2016).

Lu, M. Y. et al. A visual-language foundation model for computational pathology. Nature Medicine 30, 863–874, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02856-4 (2024).

Chen, R. J. et al. Towards a general-purpose foundation model for computational pathology. Nature Medicine, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02857-3 (2024).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. in Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, munich, germany, october 5-9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18 234–241, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28 (Springer, 2015).

Acknowledgements

We deeply appreciate Professor Chun Wang for her invaluable guidance on the challenging cases during our annotation process. Our heartfelt thanks also go to Dr. Feng Ning and Dr. Kai Wang from the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University East Hospital for their dedicated data collection. We are grateful to Directors Guanjun Zhang, Huilin Gong, Xi Liu, and Yina Jiang for their strong support of this project. Special thanks to Xinye Pu for her valuable input on the pathological illustrations. This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province (2021GXLH-Z-095), the Innovative Research Group of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61721002), National Clinical Key Specialty Construction Project (QT298), and the Shaanxi Provincial Key Research and Development Program (2024SF-YBXM-245).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.B.W. designed the study, collected and annotated data, and wrote the manuscript. J.G. executed the algorithms, wrote the manuscript, processed and uploaded the data. C.D. annotated the data. Y.F., H.C., Z.Y., and C.R. were responsible for the pathological technical work. X.T. and X.W. collected references and scanned the slides. Z.G. and C.L. designed the study and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Ge, J., Niu, Y. et al. A fully annotated pathology slide dataset for early gastric cancer and precancerous lesions. Sci Data 12, 1326 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05679-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05679-1

This article is cited by

-

Translational deep learning models for risk stratification to predict prognosis and immunotherapy response in gastric cancer using digital pathology

Journal of Translational Medicine (2025)