Abstract

Artificial intelligence advancements have significantly enhanced computer-aided intervention, learning among surgeons, and analysis of surgical videos post-operation, substantially elevating surgical expertise and patient outcomes. Recognition systems for endoscopic surgical phases using deep learning algorithms heavily rely on comprehensive annotated datasets. Our research presents the Renji dataset featuring videos of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for colorectal neoplastic lesions (CNLs), which includes 30 procedural recordings with 130,298 phase-specific annotations collaboratively labeled by a team of three specialists in endoscopy. To our knowledge, this represents the first openly accessible collection of ESD videos specifically targeting CNLs treatment, and we anticipate this work will help establish standards for constructing similar ESD databases. Both the video collection and corresponding annotations have been made publicly accessible through the Figshare platform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide1. With the growing adoption of colonoscopy screening and advancements in AI-assisted diagnosis, the detection rate of colorectal neoplastic lesions (CNLs) has been steadily increasing2,3,4. For large lesions (>2 cm) that require en bloc resection, flat non-granular laterally spreading tumors (LST-NG) especially those with pit-depressed type, early-stage cancers with superficial submucosal invasion, fibrotic mucosal tumors, and recurrent cancers following endoscopic resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is widely recognized as the primary treatment modality5. Compared with traditional surgical methods, ESD offers less invasiveness and better post-operative life quality for individuals undergoing treatment6. However, ESD requires advanced endoscopic skills, including precise instrument manipulation based on lesion morphology, optimal endoscope positioning, and meticulous gas volume regulation in different stomach regions. Moreover, accurate identification of lesion type and extent from real-time endoscopic images is crucial7.

Endoscopist training typically progresses from theoretical knowledge to practical application on animal models before advancing to supervised procedures on patients and eventual independent practice. However, limited access to animal models and expert mentorship creates significant challenges for novice practitioners, prolonging their learning curve and potentially increasing patient risk during procedures8.

Surgical videos offer a more objective and comprehensive record of intraoperative events compared to procedural documentation alone, allowing physicians to critically analyze their surgical techniques and correlate findings with patient outcomes9,10. Artificial intelligence (AI)-driven video analysis of surgical procedures provides real-time feedback and decision support to surgeons by dissecting the progression of surgical steps on a second-by-second basis11. This technology can also identify potential risks, improving surgical safety and patient care quality12,13. For novice practitioners, AI can support skill assessment through simulated environments and analyzed operation videos, contributing to a shortened learning curve14. As a result, the field of intelligent surgical process analysis is attracting growing interest from both computer scientists and medical professionals.

Currently, research on phase recognition in ESD treatment of early gastrointestinal cancers is limited. Cao et al. annotated approximately 50 ESD video instances (201,026 frames) covering gastric, esophageal, and colon lesions to develop an AI cognitive assistance system that showed promising training results in animal studies15. Furube et al. annotated 94 esophageal ESD videos and developed a phase recognition system that achieved over 90% accuracy in two independent tests16. A recent multicenter study analyzed 195 ESD videos from seven hospitals worldwide, with their AI model achieving 89.84%, 80.62% and 74.61% accuracy in esophageal, stomach and colorectal ESD tests respectively17. However, these ESD videos were not made public, and procedural classifications remain inadequate. While the recent study included chromoendoscopy for lesion observation, it wasn’t separated from other phases, and recognition of key steps like intraoperative traction and hemostasis still needs improvement.

Considering the limited availability of public datasets for automatic phase identification in ESD for CNLs, this study aimed to establish a publicly accessible database for ESD phase recognition. This initiative enhances the efficiency of ESD process analysis by meticulously annotating 30 ESD endoscopic videos of CNLs. The primary contributions include:

-

1.

Video collection: A total of 30 surgical videos were analyzed for CNLs, detailing the distribution of cases across various anatomical regions. Specifically, 3 cases were identified in the ileocecum, 13 in the transverse colon, 6 in the ascending colon, 3 in the sigmoid colon, and 5 in the rectum.

-

2.

Comprehensive labeling: 130,298 frames received annotations, with each frame categorized according to a specific procedural phase. We believe that making this dataset publicly available will substantially advance AI research related to ESD and promote the translation of these technologies into clinical settings.

Methods

Data collection

The study analyzed data collected during standard endoscopic submucosal dissection procedures conducted at Renji Hospital’s Endoscopy Department (Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine) from May through October 2024. Patients scheduled for standard ESD procedures were approached during preoperative consultations and informed about the optional research component. Each participant signed consent documentation permitting their procedure recordings to be utilized for research purposes and open published after data collection, with participants explicitly informed that they could decline research participation while still receiving standard clinical treatment. All personal identifiers (such as ID, date, facial close-up, etc.) were subsequently anonymized to protect confidentiality. Ethical clearance was granted by Renji Hospital’s Ethics Committee (Reference: LY2024-271-B). The analysis encompassed 30 ESD procedure recordings captured with the Olympus CV-260/290 endoscopy platform and IMH-200 image management hub at 1920 × 1080 resolution and 50 frames per second (fps). Table 1 provides comprehensive specifications of endoscopic tools employed during these interventions. All footage underwent thorough screening to remove non-digestive tract imagery, while identifying elements like patient numbers and temporal indicators were carefully obscured. A highly qualified senior endoscopist, Dr. Li Xiaobo, performed all the procedures included in this investigation.

Annotations of video

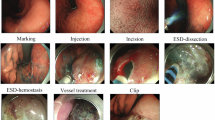

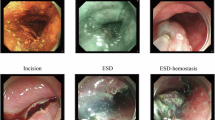

To facilitate dataset annotation, our team created a methodical protocol for documenting ESD procedures (Fig. 1, Table 2). This protocol divides the ESD process into 8 phases: (1) preparation: the interval during which clinicians adjust endoscopic equipment or exchange instruments; (2) Estimation: the initial evaluation of lesion characteristics through white light examination, magnification techniques, and NBI chromoendoscopy with optional Indigo carmine or crystal violet application (not mandatory for all ESD cases); (3) Marking: the identification of the lesion boundary, followed by placement of multiple circumferential electrocautery indicators positioned roughly 5 mm from the affected area (not required for all ESD procedures). (4) Injection: the submucosal administration of a combined solution containing physiological saline, adrenaline, or hyaluronic acid derivatives to elevate targeted tissue layers. (5) Incision: the circumferential cutting of mucosa at a measured distance of 5 mm from either the lesion itself or the previously marked region. (6) ESD: the progressive detachment of the submucosal layer from the underlying muscularis propria until complete removal and retrieval of the target tissue. Bleeding control is managed via electrocoagulation or thermal forceps as necessary, with traction-assisted methods employed when indicated; (7) vessel treatment: the management of remaining vascular structures or hemorrhage points on the exposed surface using thermal biopsy instruments; (8) Clip: the application of hemostatic clips for wound closure or suspected perforation management. Because of our substantial dataset volume, videos were downsampled to 1 fps by extracting the first frame of each second for subsequent annotation. When phase transitions occurred between consecutive sampled frames, phase boundaries were determined based on the predominant surgical activity observed in each sampled frame. Expert annotators assigned phase labels according to the most clinically significant activity present at each timestamp. Each individual frame received classification into only one of the 8 phases, determined by identifying the commencing and concluding frames of respective phases.

Data Records

Our collection underwent extensive quality verification through multiple validation steps. The complete package, accessible as a compressed file on Figshare18, contains the initial 30 endoscopic recordings alongside 130,298 annotated phase recognition sequences. For each identified action phase within individual recordings, text-formatted annotations specify beginning and concluding frames. The distribution of phase annotations across all ESD endoscopic recordings appears in Fig. 2. When accessing materials from Figshare, users will find content arranged hierarchically. The top-level organization consists of numerically labeled directories (1–30), each corresponding to a specific procedural case. These individual case directories house both the unprocessed endoscopic footage (in.mp4 format) and corresponding phase designation files (in.txt format). Additionally, Fig. 3 illustrates the cumulative temporal span of annotations for individual phases throughout the complete video collection.

Technical Validation

Dataset characteristics

The collection encompasses 30 individual procedure videos with accompanying phase classification labels, gathered from an equal number of clinical cases. Participants had a mean age of 58.7 years (SD = 8.60). The demographic distribution included 11 women and 19 men, all of Chinese nationality.

Data validation

Our classification protocol implemented a three-step verification process. In the preliminary stage, two clinically trained data specialists (Tang Cao and Jinneng Wang) conducted separate and independent classification of two video sequences containing 3119 and 5185 frames respectively, following established annotation protocols. The degree of agreement between annotators was measured using Cohen’s-Kappa statistical analysis, resulting in coefficients of 0.955 and 0.959 respectively (p < 0.001), demonstrating exceptional inter-rater consistency in applying the classification framework. Upon validation of this reliability, both annotators proceeded to independently categorize the remaining 23 procedural recordings. Following completion of all annotations, thorough quality verification was conducted by two senior endoscopists with substantial clinical expertise (Xiaobo Li and Qingwei Zhang). This validation procedure combined visual inspection with applied clinical expertise to confirm the accuracy of procedural phase designations.

Limitations of the datasets

A primary constraint of our dataset involves its single-institution origin, which restricts the diversity of acquisition parameters due to standardized equipment configurations including specific endoscope models and illumination systems. Future work will focus on expanding our repository and establishing collaborative relationships with additional clinical facilities. Despite these constraints, as the currently available public resource for ESD procedure documentation, we believe this database will make valuable contributions toward advancing automated recognition of endoscopic submucosal dissection procedural phases.

Code availability

No novel code was used in the construction of Renji dataset.

References

Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin 74, 12–49, https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21820 (2024).

Shaukat, A. et al. Computer-Aided Detection Improves Adenomas per Colonoscopy for Screening and Surveillance Colonoscopy: A Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology 163, 732–741, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.028 (2022).

Misumi, Y. et al. Comparison of the Ability of Artificial-Intelligence-Based Computer-Aided Detection (CAD) Systems and Endoscopists to Detect Colorectal Neoplastic Lesions on Endoscopy Video. Journal of clinical medicine 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12144840 (2023).

Saito, Y., Bhatt, A. & Matsuda, T. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection and its journey to the West. Gastrointest Endosc 86, 90–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2017.03.1548 (2017).

Tanaka, S. et al. Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc 32, 219–239, https://doi.org/10.1111/den.13545 (2020).

Libanio, D. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection techniques and technology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Review. Endoscopy 55, 361–389, https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2031-0874 (2023).

Mitsui, T. et al. Novel gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection training model enhances the endoscopic submucosal dissection skills of trainees: a multicenter comparative study. Surgical Endoscopy 38, 3088–3095, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-024-10838-3 (2024).

Pimentel-Nunes, P. et al. Curriculum for endoscopic submucosal dissection training in Europe: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement. Endoscopy 51, 980–992, https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0996-0912 (2019).

Ortenzi, M. et al. A novel high accuracy model for automatic surgical workflow recognition using artificial intelligence in laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair (TEP). Surgical Endoscopy 37, 8818–8828, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-023-10375-5 (2023).

Stulberg, J. J. et al. Association Between Surgeon Technical Skills and Patient Outcomes. JAMA Surgery 155, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3007 (2020).

Padoy, N. et al. Statistical modeling and recognition of surgical workflow. Medical Image Analysis 16, 632–641, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2010.10.001 (2012).

Hegde, S. R. et al. Automated segmentation of phases, steps, and tasks in laparoscopic cholecystectomy using deep learning. Surgical Endoscopy 38, 158–170, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-023-10482-3 (2023).

Guédon, A. C. P. et al. Deep learning for surgical phase recognition using endoscopic videos. Surgical Endoscopy 35, 6150–6157, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-08110-5 (2020).

Takeuchi, M. et al. Automated Surgical-Phase Recognition for Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy Using Artificial Intelligence. Ann Surg Oncol 29, 6847–6855, https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-11996-1 (2022).

Cao, J. et al. Intelligent surgical workflow recognition for endoscopic submucosal dissection with real-time animal study. Nature Communications 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42451-8 (2023).

Furube, T. et al. Automated artificial intelligence-based phase-recognition system for esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 99, 830–838, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2023.12.037 (2024).

Liu, R. et al. Artificial intelligence-based automated surgical workflow recognition in esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection: an international multicenter study (with video). Surg Endosc, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-025-11644-1 (2025).

Chen, J. et al. Renji endoscopic submucosal dissection video data set for colorectal neoplastic lesions. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28737686 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Medical Engineering Cross Research Fund of Shanghai Jiaotong University (YG2025ZD01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Initiating and managing the Renji dataset project was handled by Jinnan Chen, who also conducted data analysis, established annotation protocols, and drafted the manuscript. The annotated information was examined and visually represented in figures by Xiangning Zhang. Phase identification and labeling were executed independently by both Jinneng Wang and Tang Cao. Chunjiang Gu developed the annotation methodology documentation. Collection of procedural recordings was performed by Zhao Li and Yiming Song, who additionally contributed manuscript content. Medical equipment verification and graphical visualization were managed by Liuyi Yang. Annotated information analysis and project coordination were overseen by Zhengjie Zhang. The conceptual framework for phase identification was established and annotation accuracy was confirmed by Qingwei Zhang. Dahong Qian supervised annotation concept development and project coordination. The ESD procedures were conducted by Xiaobo Li, who also validated the annotated materials and directed the overall research endeavor.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors affirm that they do not have any known conflicting financial interests or personal relationships that could be perceived as influencing the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Zhang, X., Wang, J. et al. Renji endoscopic submucosal dissection video data set for colorectal neoplastic lesions. Sci Data 12, 1366 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05718-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05718-x