Abstract

Tropical cyclones (TCs) are among the most destructive weather phenomena, significantly impacting atmosphere-ocean interactions and coastal regions. Accurate and high-resolution TC wind field datasets are critical for enhancing storm forecasting, disaster risk assessment, and understanding ocean-atmosphere interactions. Existing reanalysis datasets, such as ERA5, typically underestimate peak wind speeds and inadequately capture inner-core structural characteristics of TCs. To address these limitations, we introduce a globally applicable, high-resolution TC wind field dataset reconstructed from ERA5 through an integrated parametric correction approach. This novel methodology combines the Willoughby adjustment for open-ocean TCs, proportional correction methods for landfalling TCs, and a linear interpolation method to ensure smooth transitions in coastal regions. Comprehensive validation against satellite-based measurements (SMAP and WindSat), airborne observations (SFMR), and ground-based meteorological data demonstrates substantial enhancements in the accuracy of reconstructed TC tracks, maximum wind speeds, and radius of maximum wind. The resulting dataset provides significant improvements in representing global TC dynamics, and serving as a valuable resource to advance TC forecasting, climate modeling, and disaster resilience strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Tropical cyclones (TCs) are among the most devastating natural hazards, causing significant socioeconomic impacts, including severe damage to infrastructure and economic losses in affected regions1,2. Accurate representation of TC wind fields is crucial not only for improving storm forecasting and risk assessment, but also for enhancing predictions of oceanic responses, such as storm surge, cold upwelling, and wind-driven ocean mixing3. Furthermore, precise TC wind field data play a fundamental role in assessing coastal vulnerabilities and strengthening disaster preparedness strategies.

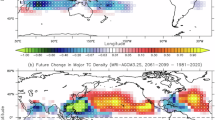

TC-induced atmospheric forcing profoundly influences the upper ocean, resulting in sea surface cooling, increased vertical mixing, and significant momentum and heat fluxes3,4,5,6,7. At larger scales, TCs contribute to meridional heat transport, influencing large-scale atmosphere-ocean interactions and potentially modulating global climate variability8,9. As the climate warms, the intensity, frequency, and structural characteristics of TCs have exhibited complex changes6,10,11,12,13, highlighting the need for more accurate wind fields in climate models to better capture TC–ocean and deep-water interactions.

With advancements in satellite observation technology, numerical modeling, and data assimilation techniques, reanalysis datasets such as the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Reanalysis V5 (ERA5) and the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP), have provided valuable information for characterizing TC properties. However, these datasets often fail to resolve the full complexity of TC wind fields, particularly within the inner-core region, where the strongest winds are concentrated14. Due to their relatively coarse spatial resolution (available around 0.25°), these datasets struggle to accurately represent key structural features such as the radius of maximum wind (RMW) and the asymmetric distribution of winds, often leading to underestimated peak wind speeds and poorly defined storm cores15,16.

To address these challenges, various methods have been proposed. Traditional parametric models, such as the symmetric Holland model17 and the generalized asymmetric Holland model18, have been widely applied for wind field reconstruction. However, these models often fail to account for terrain-induced modifications, particularly for landfalling TCs19,20. The proportional correction method has improved the consistency between model outputs and observations, but it tends to overestimate the size of the inner-core region compared to satellite-based wind estimates21,22. More recently, hybrid statistical-dynamical approaches have been developed, integrating data assimilation techniques to improve wind field estimates, yet their applicability remains constrained by observational uncertainties23,24. In parallel, deep learning-based models, such as Aurora25 and Pangu-Weather26, have demonstrated promising capabilities in improving weather forecasting accuracy. Although machine learning methods are increasingly explored for TC prediction27,28,29, capturing TC intensity accurately remains challenging due to the limited availability of high-quality training data and the inherent complexity of TC dynamics30,31,32. Therefore, physics-based models remain indispensable for improving TC wind field representation, particularly for extreme events and rapid intensification scenarios.

Here, we developed a novel TC wind field dataset developed by integrating multiple parametric correction methods to improve the global representation of TC wind structures in ERA5 reanalysis. Our methodology uniquely combines the Willoughby adjustment for open-ocean scenarios, proportional corrections optimized for landfall events, and a linear interpolation method that ensures smooth transitions in nearshore regions. This integrated approach substantially improves the representation of TC wind fields across diverse geographical contexts, as demonstrated through rigorous validation against satellite observations (SMAP, WindSat), airborne measurements (SFMR), and ground-based station data. The validation process confirms significant enhancements in key parameters such as maximum wind speeds, radius of maximum winds, and storm track accuracy.

This study provides a more reliable dataset for future TC research and forecasting, offering significant improvements over the original ERA5 in terms of wind speed and storm structure representation. Enhanced accuracy of TC wind fields would profoundly affect the representation of critical ocean processes such as sea surface cooling, vertical mixing, and upper-ocean stratification. The improved resolution of wind intensity and radial structure provided by this dataset can significantly influence numerical ocean models, refining their predictions of TC-induced sea surface temperature anomalies and inertial wave generation. Accurate representation of such oceanic responses is essential for comprehending broader impacts on marine ecosystems, biogeochemical cycling, and coastal vulnerability, especially under changing climate conditions.

Methods

TCs best track data

In this study, we utilize the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS) dataset (https://doi.org/10.25921/82ty-9e16), specifically Version 4r00 in NetCDF format, provided by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)33. IBTrACS is a comprehensive global dataset of TCs, including typhoons, hurricanes, and tropical storms. It provides 3-hourly TC center locations (\({x}_{c},{y}_{c}\)), Maximum sustained Wind Speed (MWS), RMW and minimum distance to land between current and next location (\({D}_{{land}}\)). Although the dataset provides the radius of 34-knot winds (\({R}_{34}\)), it is excluded from the validation in this study due to historical inconsistencies in quality control. Specifically, \({R}_{34}\) values have only been subjected to systematic post-season reanalysis and quality assurance in recent years, limiting their reliability for long-term assessments. We select TC data from the period 1993–2022, reported by U.S. meteorological agencies. Records lacking MWS values are excluded, resulting in 2,932 valid TC tracks in total, with 2,163 tracks in the Northern Hemisphere and 769 in the Southern Hemisphere. To ensure temporal consistency with the wind data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis V5 (ERA5, https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.bd0915c6)34, the TC data were linearly interpolated into hourly intervals.

Soil moisture active passive data

The Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) platform and mission were launched on January 31, 2015, and began observations soon in April 201535. Although SMAP was designed primarily to measure soil moisture from space, its L-band radiometer also enables the retrieval of sea surface salinity and sea surface wind speed (Fig. 1a). This paper selects SMAP data to correct the MWS and RMW of TCs in 2020 (https://www.remss.com/missions/smap/winds). The SMAP data has a temporal resolution of 12 h and a spatial resolution of 0.25°. Each data file consists two 0.25° gridded daily wind speed maps, corresponding to ascending (local equatorial crossing time 18:00) and descending (local equatorial crossing time 06:00) track segments. Observations are limited to those with UTC times falling within the respective UTC day, with observation times recorded as minutes since midnight. The SMAP Wind Speed Data product is particularly suited for studying higher wind speeds.

WindSat TC-winds data

The WindSat TC-Winds dataset was developed in 2020 and processed throughout the duration of the WindSat mission (2003-present, https://remss.com/tropical-cyclones/tc-winds)36. SMAP and WindSat share approximately the same ascending node (equatorial crossing) time, allowing for temporal consistency between the two datasets. The WindSat TC-winds are provided as daily global 0.25° gridded maps in NetCDF4 format, divided into ascending and descending channels (Fig. 1b). The TC-Winds data is only valid over warm waters (Sea Surface Temperature > 20 °C) and for wind speeds above 10 m/s, reflecting its design for capturing TC conditions.

Stepped frequency microwave radiometer data

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)/Hurricane Research Division’s Stepped Frequency Microwave Radiometer (SFMR, https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/data_sub/hurr.html) is a new generation airborne remote sensing instrument used to estimate the ocean surface brightness temperatures at six frequencies between 4.6 and 7.2 GHz in hurricanes37. The sea surface wind speeds along the aircraft flight track are then retrieved using a functional relationship between wind speed and these brightness temperatures. The retrieval accuracy of revised SFMR surface wind speeds is improved within approximately 3.9 m/s root-mean square error (RMSE) compared to collocated dropsonde observations. SFMR thus provides high-resolution wind profiles of TCs, providing an important reference for verifying the reconstructed wind field in this study.

In-situ meteorological data

In this study, we use observational wind speed with hourly resolution from three in-situ meteorological stations in Zhejiang, China (S1-S3, Fig. 2), providing by the Meteorological Bureau of Ningbo, Zhejiang Province. Ten TC event cases are selected to assess the performance of different reconstructed wind field in representing actual TC wind scenarios (Table 1).

Conversion between different wind averaging periods

It is important to account for the fact that surface wind speed data from different sources are reported using varying temporal averaging periods. For example, the maximum wind records in IBTrACS are 1-minute averages, SMAP and WindSat TC-wind data are 10-minute averages, SFMR measurements are of second-level resolution, and ERA5 provides 1-hour averaged winds. To ensure consistency across datasets, we employed the empirical conversion factors (Table 2) recommended by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) to standardize all wind speed values to a common averaging period38. Specifically, all values were converted to a 1-hour averaging interval, the coarsest temporal resolution among the datasets, to facilitate direct and meaningful comparison.

The reconstruction methods of TC wind field

To address ERA5 limitations, we propose an integrated parametric method for reconstructing TC wind fields, explicitly tailored for global application. The method distinguishes between TC dynamics across open ocean, landfalling, and nearshore regions to capture realistic storm structures effectively.

For TCs located over the open ocean with ideal dynamic structure, the reconstructed ERA5 wind field is derived by using ERA5 wind data and an idealized wind model specific to oceanic conditions. The radial wind profile of the TC is estimated using the Willoughby adjustment method24, which approximates gradient wind balance based on the Holland model. The gradient wind at radius r is given by:

where \({V}_{g}\) is the gradient wind at radius \(r\), and \(\varphi \) represents the latitude of the TC center. For TC records lacking valid RMW values, the RMW is estimated using the empirical relationship proposed by Willoughby & Rahn (2004)24:

To integrate the ERA5 data with the idealized TC wind radial profile model, we adopt a blending approach using a weight coefficient α, following the method proposed by Chu & Cheng (2007)39. The assimilation is expressed as

where \({V}_{t}\) is the TC translation speed, calculated from the IBTrACS dataset. In this study, \({V}_{t}\) is set to zero when TC’s MWS is less than 33 m/s, to reduce potential biases in the reconstructed wind field. The weight coefficient α (Fig. 3a) is defined as

where r is the radial distance from the TC center and n is a non-dimensional tuning parameter. Previous studies have shown that setting n = 4 provides a realistic representation of the TC dynamic structure in oceanic regions40,41.

Over land, the presence of complex terrain can significantly distort the idealized radial structure of TC winds, making the Willoughby adjustment method and other idealized parametric wind models less applicable. To address this limitation, we adopt an empirical proportional correction approach similar to that described by Li et al. (2022)22. This method utilizes an empirically derived adjustment factor to enhance the TC wind intensities, while maintaining the underlying spatial structure of the original ERA5 wind field. Previous studies have shown that this approach performs well in reducing estimation errors21,22. The enhancement ratio can be expressed as follows:

where \({V}_{\max E}\) is the MWS calculated from ERA5. The corrected wind field \({V}_{{Li}}(r)\) is then calculated as

As illustrated in Fig. 3b, the adjusted wind speed \({V}_{{Li}}\) varies with radial distance under different enhancement ratios. Specifically, \({V}_{{Li}}\) equals the observed maximum wind speed \({V}_{\max }\) at RMW (i.e. \(r={R}_{\max }\)) and gradually converges to the original ERA5 wind field outside the enhancement zone or when the ratio approaches one. This formulation ensures both continuity and stability, effectively preserving the spatial structure inherent in ERA5 while improving intensity estimation in landfall scenarios.

To integrate the aforementioned methods and ensure smooth transitions between oceanic and land-based corrections, a linear interpolation is applied. This approach mitigates abrupt discontinuities and allows for the generation of a spatially continuous final wind field. The interpolation is formulated as follows:

where ω is weight parameter, defined as follows:

where \({d}_{1}\) is set to 100 km (the global average of \({R}_{34}\)), representing the distance at which the TC’s dynamic structure begins to be influenced by topography.

Calculation of maximum TC wind speed and its corresponding radius from satellite data

Based on the TC center positions provided by the IBTrACS, this study utilizes TC-Winds satellite imagery from SMAP and WindSat, covering a 10° × 10° region centered on the IBTrACS location, to independently estimate the MWS and RMW. To refine the TC center position in satellite wind fields, a 4° × 4° sub-region centered on the IBTrACS location is further analyzed. Within this domain, the grid point with the minimum wind speed is identified and designated as the satellite-estimated TC center. This estimated center is not used to correct or modify the IBTrACS position, but instead serves as a reference for evaluating the positional accuracy of the satellite data.

Next, the MWS is estimated by calculating the mean of the top 5% of wind speeds within the selected region. An isoline map of the wind field is generated, and the RMW is determined by computing the average distance between the refined TC center and the surrounding isoline contours. This approach enables accurate identification of the TC center, MWS, and the associated RMW, providing valuable information for tropical cyclone research and wind field reconstruction.

Refine the TC parameters from reanalysis wind data

Due to systemic errors in ERA542, it is necessary to refine key TC parameters, including the TC center position and MWS. To refine the TC center, we first select a 10° × 10° grid centered around the TC position provided by IBTrACS. This grid includes both zonal (u) and meridional (v) wind components. Within this region, relative vorticity (\(\zeta =\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial u}{\partial y}\)) is computed. The refined TC center is defined as the location where the wind speed is minimum and the relative vorticity exceeds the regional average. Next, based on the refined TC center, \({V}_{\max E}\) is calculated using wind speed data within a 4° × 4° region surrounding the new center. The mean of the top 5% of wind speed values within this region is used to determine \({V}_{\max E}\).

For the reconstructed ERA5 wind field, the MWS is further refined by analyzing wind speed as a function of radial distance from the TC center. The RMW is calculated by identifying the position of MWS in the radial direction. Additionally, the \({R}_{34}\) for each TC is calculated in four quadrants (Northeast, Southeast, Southwest, and Northwest). The method for calculating \({R}_{34}\) is identical to that used for RMW, relying on the same data map to derive the distances.

Data Records

The Reconstructed ERA5 wind field and the refined TC trajectory dataset have been published and are available through Zenodo repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1584465543. The dataset has a total size of 10.08 GB (referring only to data files in NetCDF format) and consists of two folders. One folder contains the reconstructed TC wind fields extracted from the reconstructed ERA5 wind field dataset (TC_snapshot.zip). The archive can be extracted using the unzip command on Linux/macOS or the File Explorer on Windows. Each file corresponds to a single TC track and includes all associated snapshots, with the filename corresponding to the TC identification number in the IBTrACS dataset, which is also included in the data repository. If users wish to reconstruct the complete corrected global wind field, they can overlay these TC snapshots onto the original ERA5 gridded dataset by directly replacing the corresponding grid points affected by the TC. The second folder contains the refined TC tracking dataset (TC_track.nc), which was generated using the methods described in the Methods section and includes the redefined TC parameters at each snapshot time.

TC wind field file (TC_snapshot.zip)

-

(1)

Longitude: Longitudes of the TC wind field.

-

(2)

Latitude: Latitudes of the TC wind field.

-

(3)

Time: Date of the detected TC (expressed as serial date numbers, with a base date of January 0, 0000, following the proleptic ISO calendar).

-

(4)

Zonal velocity: Zonal component of TC wind field at 10 meters above the sea surface, defined as positive eastward (unit: m/s).

-

(5)

Meridional velocity: Meridional component of TC wind field at 10 meters above the sea surface, defined as positive northward (unit: m/s).

TC information file (TC_track.nc) (Note: If a value is unavailable, it is represented as NAN)

-

(1)

Center longitude: Longitude of TC center.

-

(2)

Center latitude: Latitude of TC center.

-

(3)

Maximum wind speed: Azimuthally averaged maximum wind speed around TC center (unit: m/s).

-

(4)

The radius of maximum wind speed: Distance between the TC center and location of the maximum wind speed (unit: km).

-

(5)

The radius of 34-knot wind speed: Estimated in four quadrants (northeast, southeast, southwest, and northwest) (unit: km).

-

(6)

The refined wind speed: Average wind speed of Top 5% of values around TC center (unit: m/s).

Technical Validation

Data assessment

In this study, method performance is assessed using three common metrics: Bias, RMSE and Correlation coefficient (R). These metrics are defined by the following equations:

where \({y}_{i}\) and \(\bar{y}\) represent the true value and mean value. \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) and \(\bar{\hat{y}}\) are the reanalysis wind field value and observational value. N denotes the total number of samples.

The SMAP and windsat validity assessment

To assess the reliability of TC wind fields derived from SMAP and WindSat, we compared their estimates of MWS and RMW with the TC parameters provided by IBTrACS, widely recognized as a robust reference for global TC characteristics. Figure 4a demonstrates that SMAP provides a strong correlation (R = 0.91) with IBTrACS in estimating MWS, with a RMSE of 5.31 m/s and a negative bias of −2.66 m/s. This high correlation suggests that SMAP reliably captures the TC wind field, with a slight underestimation of MWS. In contrast, Fig. 4c shows that WindSat also exhibits a moderate correlation (R = 0.75) with IBTrACS for MWS, but with a larger RMSE of 7.68 m/s and a more pronounced negative bias of −3.98 m/s. These results suggest that while WindSat provides valuable insights into TC wind fields, it tends to underestimate the MWS to a greater extent than SMAP.

When examining the RMWs derived from SMAP and WindSat, both datasets show strong correlations with IBTrACS (R = 0.75 for SMAP and R = 0.80 for WindSat) as shown in Fig. 4b and Fig. 4d. Although the RMSEs for RMW estimation are relatively large, with WindSat exhibiting an RMSE of 27.47 km and SMAP showing an RMSE of 30.56 km, both datasets capture the general trend of RMW well, with WindSat showing a slight overestimate while SMAP demonstrating a more moderate bias. These findings suggest that while some discrepancies in the RMW estimation, both satellite-derived products closely track the spatial variability in RMW reported by IBTrACS.

Overall, both SMAP and WindSat offer valuable estimates of MWS and RMW, with SMAP showing better performance in MWS estimation. Although some error remains, particularly in the estimation of RMW, these satellite datasets provide reliable observational references for validating reconstructed ERA5 wind profiles.

The reconstructed TC wind field accuracy assessment

A comparison of the wind field structure corrected by different methods across various regions is shown in Fig. 5. Compared to the original ERA5 dataset, the reconstructed wind fields provide a more refined representation of the TC inner-core structure, better resolving fine-scale features such as the RMW and wind speed asymmetry. To evaluate the effectiveness of the reconstructed TC wind fields, various observational datasets, including remote sensing-derived wind profiles and in-situ measurements, are used for validation.

Comparison of typhoon TRAMI wind fields derived from ERA5 and reconstructed ERA5 at different time steps. (a–c) are derived from ERA5 and (d–f) are derived from the reconstructed ERA5. The left column represents TCs in the open ocean, the center column represents near-shore TCs, and the right column displays the TCs approaching land. The color scale indicates wind speed (unit: m/s), and the vectors represent wind direction and speed.

Comparison of TCs in the open ocean and near-shore

In this study, we compare TC wind speed profiles derived from the original ERA5, reconstructed ERA5, SFMR, SMAP, and WindSat datasets to assess the accuracy of TC wind field estimates over the open ocean and near-shore regions. The SFMR data (blue line) reveals a clear wind field structure in both the inner and outer regions of the TC, with peak wind speeds occurring just outside the RMW, forming an asymmetric double-peak structure (Fig. 6a–f). In contrast, the original ERA5 data (red line) significantly underestimates the wind intensities within the inner core of the TC (roughly 3 times the RMW), with wind speeds much lower than those observed by SFMR.

Wind speed profiles for several TC events at different times, as observed by the Stepped Frequency Microwave Radiometer (SFMR, blue lines), compared with wind fields extracted from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset (red lines) and the reconstructed wind field from ERA5 (RE-ERA5, orange lines). Each panel (a–f) represents a specific TC event at the indicated time, with the corresponding storm name labeled and wind speeds plotted against latitude. (g) ERA5 wind speed vs SFMR wind speed. (h) Reconstructed ERA5 wind speed vs SFMR wind speed. The color represents the sample number.

The reconstructed wind field significantly mitigates this underestimation observed in the original ERA5 dataset. The reconstructed ERA5 (orange line) exhibits a clearer bimodal structure and provides a more accurate representation of the minimum wind speed near the TC center, aligning more closely with SFMR observations. The comparison of all TC events observed by SFMR shows consistent underestimation in the original ERA5 (Fig. 6g, bias < −11 m/s), while the reconstructed ERA5 effectively reduces this issue (Fig. 6h, bias < 1 m/s). These findings underscore the effectiveness of the wind field correction method, demonstrating improved agreement between the reconstructed ERA5 and independent observation data.

Since SFMR data primarily limited to the Atlantic region, we further validated the reconstructed TC wind fields using satellite-based datasets from SMAP and WindSat, which have been independently validated for TC wind speed estimation in global regions. Similar to SFMR, several TC events were selected to compare the reconstructed results (Fig. 7a–h). The comparisons again show that the reconstructed ERA5 data more closely align with SMAP and WindSat data. A global assessment of all satellite-observed TC events (Fig. 7i,j) reveals a consistent underestimation in the original ERA5, while the reconstructed ERA5 significantly reduces this underestimation. These findings further support the robustness of the reconstructed wind field data in representing the true global TC wind structure.

Wind speed profiles for several TC events at different times, as observed by the Satellite data (blue lines), compared with wind fields extracted from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset (red lines) and the reconstructed wind field from ERA5 (RE-ERA5, orange lines). The left column represents TCs observed by SMAP. The right column represents TCs observed by Wind. (i) ERA5 wind speed vs Satellite wind speed including SMAP and WindSat. (j) Reconstructed ERA5 wind speed vs Satellite wind speed. The color represents the sample number.

Comparison of TCs on land

Accurate representation of TC wind fields during landfall is essential for hazard assessment, disaster mitigation, and enhancing forecasting models. When TCs are landfalling, their structure becomes much more asymmetric, and the radial wind profile can no longer be accurately described by idealized models. To address this challenge, we have applied the proportional method to correct the ERA5 data, with the goal of restoring a more realistic wind field structure. When compared with both the original ERA5 and new wind field corrected by Willoughby adjustment method (ERA-W), the latter performs better at correcting the TC wind field but generally overestimate wind speeds in most cases (Fig. 8). In contrast, our proposed integrated reconstruction approach (RE-ERA5), which combines proportional corrections for land regions with the Willoughby adjustment for open-ocean scenarios, demonstrates marked improvement. Specifically, RE-ERA5 more accurately captures observed peak intensities and temporal variability, while substantially reducing the wind speed overestimation observed in ERA5-W. These results underscore the robustness of our weight-based fusion method, particularly valuable for representing the complex dynamics of TCs as they transition from ocean to land.

Further quantitative assessments across ten representative TC events (Table 3) corroborate these improvements. Although the ERA5 wind fields show high correlation values in some cases (R > 0.7), they significantly underestimate wind speeds. This is particularly evident for stronger TCs, as indicated by higher RMSE and negative bias values (Table 1 and Table 3). In contrast, the proposed integrated reconstruction (RE-ERA5) systematically reduces these errors, achieving higher correlations (up to R = 0.86), lower errors (RMSE as low as 1.56 m/s), and lower bias on average, demonstrating balanced and reliable wind representations. These validation results provide compelling evidence for the superiority of the integrated approach in accurately reconstructing landfalling TC wind fields.

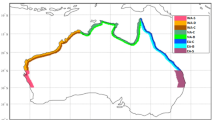

TCs Track Data Based on reconstructed ERA5

The comparison of TC tracks derived from IBTrACS observations, the original ERA5 and the reconstructed ERA5 reveals significant improvements in the representation of TC trajectories. The TC tracks from the reconstructed ERA5 dataset show better agreement with observed trajectories, particularly in regions where the original ERA5 underestimated storm intensity (Fig. 9). This improvement suggests that the enhanced wind field representation in the reconstructed ERA5 contributes to more realistic storm movement simulations, thereby providing a more reliable dataset for TC track analysis and forecasting.

Regarding wind speed estimates, the reconstructed ERA5 notably improves the representation of MWS across different storm categories (Fig. 10a). The wind speeds from the reconstructed dataset closely match IBTrACS observations, particularly for tropical depressions (TD), tropical storms (TS), and lower-category hurricanes (C1-C2) (Fig. 10b,c). However, for more intense TCs (C3-C5), the reconstructed ERA5 still slightly underestimates the MWS compared to IBTrACS (Fig. 10d), though the overall agreement remains favorable. This underestimation is primarily due to the fact that stronger TCs tend to have a more concentrated inner-core wind field, which is challenging to resolve using the relatively coarse spatial resolution of current reanalysis datasets. The reconstructed ERA5 dataset also exhibits minimal deviations from IBTrACS in terms of RMW (Fig. 10e), further validating its ability to represent the true TC wind field.

(a) Comparisons of maximum wind speed calculated from ERA5 (blue line) and Reconstructed ERA5 (red line) with corresponding results of IBTrACS., with the shaded region indicating the 95% confidence interval. (b) Wind speed in Tropical Depressions and Tropical Storms (TD&TS) for different oceanic regions: Western Pacific (WP), Eastern Pacific (EP), North Atlantic (NA), Northern Indian Ocean (NI), South Indian Ocean (SI), and South Pacific (SP). (c) Wind speed in Categories C1-C2 for different oceanic regions. (d) Wind speed in Categories C3-C5 for different oceanic regions. (e) Radius of maximum wind (RMW) for different oceanic regions. The error bars in (b) to (e) represent the 5th and 95th percentiles of the data distribution.

Code availability

Custom scripts and codes used in this study are available at GitHub (https://github.com/Liugbb/Tropical-Cyclone/tree/main). All data processing and calculations in the process of constructing the dataset are completed by MATLAB R2022b (http://www.mathworks.com).

References

Gray, W. M. Global view of the origin of tropical disturbances and storms. Mon Weather Rev 96, 669–700 (1968).

Price, J. F. Upper ocean response to a Hurricane. J Phys Oceanogr 11, 153–175 (1981).

Zhang, H., He, H., Zhang, W.-Z. & Tian, D. Upper ocean response to tropical cyclones: a review. Geosci Lett 8 (2021).

Lin, J.-Y. et al. Typhoon induced mesoscale cyclonic eddy a long neglected linkage between atmosphere ocean and climate. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8 (2025).

Lu, X. et al. Observational Analysis of Vertical Heat Flux Caused by Typhoon‐Induced Near‐Inertial Waves Under the Modulation of Mesoscale Eddies. J Geophys Res: Oceans 129 (2024).

Wang, G., Wu, L., Mei, W. & Xie, S.-P. Ocean currents show global intensification of weak tropical cyclones. Nature 611, 496–500 (2022).

Yuan, S., Yan, X., Zhang, L., Pang, C. & Hu, D. Observation of Near‐Inertial Waves Induced by Typhoon Lan in the Northwestern Pacific: Characteristics, Energy Fluxes and Impact on Diapycnal Mixing. J Geophys Res: Oceans 129, (2024).

Jansen, M. & Ferrari, R. Impact of the latitudinal distribution of tropical cyclones on ocean heat transport. Geophys Res Lett 36, (2009).

Navarra, A. et al. Effects of Tropical Cyclones on Ocean Heat Transport in a High-Resolution Coupled General Circulation Model. J Clim 24, 4368–4384 (2011).

Elsner, J. B., Kossin, J. P. & Jagger, T. H. The increasing intensity of the strongest tropical cyclones. Nature 455, 92–95 (2008).

Jian D. et al. Projected Poleward Migration of Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Genesis. Geophys Res Lett 51, (2024).

Shan, K., Lin, Y., Chu, P.-S., Yu, X. & Song, F. Seasonal advance of intense tropical cyclones in a warming climate. Nature 623, 83–89 (2023).

Zhao, H. et al. Decreasing global tropical cyclone frequency in CMIP6 historical simulations. Sci Adv 10, eadl2142 (2024).

Hodges, K., Cobb, A. & Vidale, P. L. How Well Are Tropical Cyclones Represented in Reanalysis Datasets? J Clim 30, 5243–5264 (2017).

Hart, R. E. & Schenkel, B. A. An Examination of Tropical Cyclone Position, Intensity, and Intensity Life Cycle within Atmospheric Reanalysis Datasets. J Clim 25, 3453–3475 (2012).

Moalafhi, D. B., Evans, J. P. & Sharma, A. Evaluating global reanalysis datasets for provision of boundary conditions in regional climate modelling. Clim Dyn 47, 2727–2745 (2016).

Holland, G. J. An analytic model of the wind and pressure profiles in hurricanes. (1980).

Ueno, T. Numerical Computations of the Storm Surges in Tosa Bay. J Oceanogr Soc Jpn 37, 61–73 (1981).

Bender, M. A., Tuleya, R. E. & Kurihara, Y. A numerical study of the effect of island terrain on tropical cyclones. Mon Weather Rev 115, 130–155 (1987).

Yeasmin, A., Chand, S. & Sultanova, N. Reconstruction of tropical cyclone and depression proxies for the South Pacific since the 1850s. Weather Clim Extremes 39, (2023).

Li, X. et al. Using Satellite Altimetry to Calibrate the Simulation of Typhoon Seth Storm Surge off Southeast China. Remote Sens 10, (2018).

Li, X. et al. Tropical Cyclone Wind Field Reconstruction and Validation Using Measurements from SFMR and SMAP Radiometer. Remote Sens 14, (2022).

Willoughby, H. E., Darling, R. W. R. & Rahn, M. E. Parametric representation of the primary hurricane vortex. Part II: A new family of sectionally continuous profiles. Mon Weather Rev 134, 1102–1120 (2006).

Willoughby, H. E. & Rahn, M. E. Parametric representation of the primary hurricane vortex. Part I: Observations and evaluation of the Holland (1980) model. Mon Weather Rev 132, 3033–3048 (2004).

Bodnar, C. et al. A Foundation Model for the Earth System. Nature, 1-8 (2025).

Bi, K. et al. Accurate medium-range global weather forecasting with 3D neural networks. Nature 619, 533–538 (2023).

Eusebi, R., Vecchi, G. A., Lai, C.-Y. & Tong, M. Realistic tropical cyclone wind and pressure fields can be reconstructed from sparse data using deep learning. Commun Earth Environ 5, (2024).

Vosper, E. et al. Deep Learning for Downscaling Tropical Cyclone Rainfall to Hazard‐Relevant Spatial Scales. J Geophys Res: Atmos 128, (2023).

Xu, Z. et al. Global tropical cyclone size and intensity reconstruction dataset for 1959–2022 based on IBTrACS and ERA5 data. Earth Syst Sci Data 16, 5753–5766 (2024).

Ben Bouallègue, Z. et al. The Rise of Data-Driven Weather Forecasting: A First Statistical Assessment of Machine Learning–Based Weather Forecasts in an Operational-Like Context. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 105, E864–E883 (2024).

Bonavita, M. On Some Limitations of Current Machine Learning Weather Prediction Models. Geophys Res Lett 51, (2024).

Kochkov, D. et al. Neural general circulation models for weather and climate. Nature 632, 1060–1066 (2024).

Knapp, K. R., Kruk, M. C., Levinson, D. H., Diamond, H. J. & Neumann, C. J. The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS). Bull Am Meteorol Soc 91, 363–376, https://doi.org/10.25921/82ty-9e16 (2010).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.bd0915c6 (2023).

Meissner, T., Ricciardull, L. & Wentz, F. Remote Sensing Systems SMAP daily Sea Surface Winds Speeds on 0.25 deg grid, Version 01.0. [NRT or FINAL], https://www.remss.com/missions/smap/winds (2018).

Remote Sensing Systems (RSS). TC-WindSat: Near-surface ocean wind speed retrievals for tropical cyclones. https://remss.com/tropical-cyclones/tc-winds (2020).

NOAA Hurricane Research Division. Stepped-Frequency Microwave Radiometer (SFMR) flight-level wind and rain rate data, https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/data_sub/hurr.html (2018).

Harper, B. A., Kepert, J. D. & Ginger, J. D. Guidelines for converting between various wind averaging periods in tropical cyclone conditions. WMO Tech Doc WMO/TD-1555 (2010).

C. CP, KUO-FENG C. South China Sea wave characteristics during Typhoon Muifa passage in winter 2004. J Oceanogr 64, 1-21 (2008).

Du, M., Hou, Y., Qi P. & Wang, K. The impact of different historical typhoon tracks on storm surge: A case study of Zhejiang, China. J Mar Syst 206, (2020).

Sun, R., Hou, Y., Li, J. & Hu P. The simulation of a typhoon wave in the northern part of the South China Sea. Marine Sciences 37, 76–83 (In Chinese) (2013).

Chen, G. et al. Performance of tropical cyclone forecast in western North Pacific in 2015. Trop Cyclone Res Rev 5, 47–57 (2016).

Liu, G. et al. A Global ERA5-based Tropical Cyclone Wind Field Dataset Enhanced by Integrated Parametric Correction Methods. Zendo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15844655 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42276029) and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20240813094213018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.L. and S.J. carried out the data analysis. G.L. and P.Z. conceived of the initial idea. G.L. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the research question, revisions, and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, G., Jiang, S., Zheng, M. et al. A Global ERA5-based Tropical Cyclone Wind Field Dataset Enhanced by Integrated Parametric Correction Methods. Sci Data 12, 1429 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05789-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05789-w