Abstract

Understanding the potential impact of climate change on species distributions is crucial for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management. Rodents, as one of the most diverse and widespread mammalian groups, play a critical role in ecological systems but also pose significant risks to agriculture systems and public health. Here, we present GridScopeRodents, a high-resolution global dataset projecting the distribution of 10 rodent genera from 2021 to 2100 under four CMIP6-based Shared Socioeconomic Pathway–Representative Concentration Pathway (SSP–RCP) scenario combinations. Using occurrence data and environmental variable, we employ the Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) algorithm within the species distribution modeling (SDM) framework to estimate occurrence probability at a spatial resolution of 1/12° (~10 km). The dataset encompasses four SSP–RCP scenarios (SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, SSP585) and 10 global climate models (GCMs), providing projections at 20-year intervals. GridScopeRodents serves as a valuable resource for research on biodiversity conservation, invasive species monitoring, agricultural sustainability, and disease ecology. The dataset is publicly available in GeoTIFF format and can be accessed via Figshare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Climate change is affecting ecosystems globally in diverse and interrelated ways. It is manifested in rising temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and increased climate variability. These changes can reshape species distributions, population dynamics, and ecological processes1. For example, fluctuations in temperature and precipitation may alter local plant productivity and habitat conditions, thereby influencing food availability and energy flow across trophic levels2,3. Climate change also threatens the provision of essential ecosystem services such as water regulation, air purification, and soil fertility maintenance. Increasing climate variability may reduce the regulatory capacity of ecosystems, with evidence of degradation in sensitive biomes such as tropical rainforests, potentially leading to losses in biodiversity and ecosystem functionality4,5,6. More notably, climate change poses challenges to species’ adaptability to local climatic conditions, potentially resulting in the extinction or range contraction of some species, while enabling others to expand their distribution7,8,9. In temperate regions, for instance, warm-adapted species may expand poleward or upward in elevation, causing biological invasion, while cold-adapted species may experience habitat loss and population decline.

Rodents, as the most diverse and widespread mammalian order, have successfully adapted to virtually all ecosystems across the globe10,11,12. Climate change profoundly influences their distribution and population dynamics by altering ecological niche factors, including habitat conditions, food resources, and biotic interactions13,14. Projecting rodent distributions is of critical importance in ecology, public health, and agriculture, and its urgency has become increasingly pronounced with the accelerating impacts of global climate change. Specifically, due to their high environmental adaptability, rodents may shift their distributions to higher latitudes or elevations, potentially triggering biological invasions and disrupting the stability of immigrated ecosystems12,15. Additionally, many rodent species, such as Rattus, act as natural hosts or vectors for several zoonotic diseases, including Yersinia pestis, hantavirus, leptospirosis, and Lyme disease. The dynamics of rodent populations have been strongly associated with Yersinia pestis outbreaks in parts of Africa and Asia16,17,18. Furthermore, rodent species from the families Cricetidae and Muridae have long posed significant threats to agriculture by establishing habitats in the margins of farmland and uncultivated areas, eventually invading croplands and causing substantial crop damage and agricultural losses19,20. Therefore, accurately mapping the spatial distribution of key rodents is both necessary and urgent.

Ecological Niche Modeling (ENM) is an effective approach for projecting species distributions, helping researchers understand spatial distribution patterns and project species’ potential ranges under future changes in environment21. ENM employs mathematical and statistical approaches to construct Species Distribution Models (SDMs) that project suitable habitats for species based on known occurrence records and environmental variables22,23. However, ENM is highly dependent on extensive observational data, including georeferenced species occurrence records and environmental conditions, and is sensitive to spatial resolution and scale24. Data incompleteness, spatiotemporal inconsistencies in existing datasets, variations in spatial scale (e.g., regional vs. global), and underlying model assumptions introduce gaps and quality issues in ENM, directly contributing to discrepancies in projection outcomes and accuracy25,26. A key challenge in global-scale species distribution projections is reducing reliance on extensive observational data. The Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) algorithm, a widely used machine-learning algorithm for ENM, effectively balances these challenges and has been recognized as a practical and robust projection modeling approach17,27,28,29.

Here, leveraging global species distribution records and environmental datasets, we employ MaxEnt to develop a high-resolution (1/12°) gridded dataset projecting the distribution of key rodent genera from 2021 to 2100. These projections are updated at 20-year intervals under four SSP–RCP scenarios (SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, and SSP585) and 10 global climate models (GCMs). To our knowledge, this study is among the first to apply CMIP6 SSP–RCP scenario combinations in a global-scale, gridded rodent distribution projection. By providing spatially explicit rodent distribution estimates under different future climate scenarios, this dataset serves as a valuable resource for biodiversity research, agroecosystem sustainability studies, and disease ecology investigations.

Methods

Overall framework

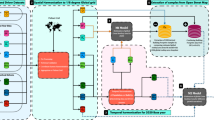

Figure 1 illustrates the methodological framework for generating this high-resolution global dataset of projecting 10 rodent genera distributions. First, we selected the target species for modeling and obtained georeferenced global distribution data for representative rodents at the species level from the GBIF database for the period 1970–2000. Next, we collected historical and future environmental data, including temperature, precipitation, DEM (Digital Elevation Model), and NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) as input environmental variables. Future environmental data were derived from four SSP–RCP scenarios and 10 global climate models (GCMs). Finally, we applied the MaxEnt algorithm, optimized the model parameters, and generated global probability distribution for representative rodents at 20-year intervals from 2021 to 2100.

Overall framework for constructing the GridScopeRodents dataset using ecological niche modeling. This diagram illustrates the overall workflow for developing the GridScopeRodents dataset. It integrates species occurrence data, environmental variables, and ecological niche modeling using MaxEnt algorithm. Historical and future projections are generated under multiple SSP–RCP scenarios and GCMs, resulting in a high-resolution global dataset of rodent habitat suitability from 2021 to 2100.

Species selected and processing

We selected ten representative rodent genera for modeling: Akodon, Apodemus, Cricetulus, Mastomys, Microtus, Mus, Oligoryzomys, Peromyscus, Phyllotis, and Rattus. These genera were chosen based on four main criteria:

-

(1)

ecological or economic relevance, particularly regarding agricultural damage and zoonotic disease transmission;

-

(2)

sufficient georeferenced occurrence records (at least 300 records) to support robust MaxEnt modeling;

-

(3)

broad geographic and climatic coverage, encompassing multiple continents and major biomes; and

-

(4)

taxonomic clarity and consistency in global biodiversity databases such as GBIF and IUCN.

This selection includes both globally invasive genera (e.g., Rattus and Mus) and regionally dominant genera (e.g., Akodon, Microtus, and Phyllotis), ensuring taxonomical, ecological and biogeographic diversity in projections. A detailed summary of each genus’s ecological and economic relevance, with supporting literature, is provided in a supplementary table hosted on Figshare, titled “Rodent Genus Selection Justification (Literature)” (see Usage Notes).

Based on GBIF data, we extracted georeferenced global distribution records at the species level for these genera30. The data retrieval criteria included: “HasCoordinate is true”, “HasGeospatialIssue is false”, “OccurrenceStatus is Present”, and “TaxonKey is one of (Phyllotis Waterhouse, 1837; Mastomys Thomas, 1915; Rattus Fischer, 1803; Oligoryzomys Bangs, 1900; Peromyscus Gloger, 1841; Cricetulus Milne-Edwards, 1867; Mus Linnaeus, 1758; Akodon Meyen, 1833; Apodemus Kaup, 1829; Microtus Schrank, 1798)”, “Year 1970–2000”. The extracted dataset underwent coordinate validation and taxonomic name verification, resulting in a total of 548,571 occurrence records (see Fig. 2 for species sample sizes and distributions, with rodent images sourced from iNaturalist contributor31 and Observation.org32).

Representative rodents selected (b) and their global distribution (a). The circular phylogenetic tree displays the rodent species included in the model at the terminal nodes, annotated with the number of samples per species (b). Labels of the form “Genus + None” indicate records that could only be identified to the genus level in the original dataset.

To mitigate spatial autocorrelation and estimation bias caused by uneven sampling, and to improve model accuracy and reliability, we applied the Spatially Rarefy Occurrence Data for SDMs function in the SDMtoolbox Pro extension of ArcGIS Pro (version 3.1.6). The occurrence points for each genus were spatially rarefied to a 10 km resolution, ensuring that only one occurrence point exists within each 10 km grid cell.

Environmental variables selected and processing

We selected climate (bioclimatic variable, including temperature and precipitation), DEM (including elevation and slope), and NDVI data as input environmental variables (Table 1). In addition to climatic variables that directly influence species distributions, non-climatic factors such as elevation, slope, and NDVI also play important roles. Elevation and slope describe topographic structure, which contributes to habitat heterogeneity and potential barriers to species movement. NDVI reflects vegetation greenness and primary productivity, and serves as a proxy for food availability and habitat quality in ecosystems33,34. For future projections, elevation, slope, and NDVI were initially intended to be held constant across all scenarios, due to the lack of reliable, long-term global projections at comparable spatial resolution. This practice—combining static environmental layers with dynamic climate variables—is commonly adopted in SDM studies and has been shown to outperform models that exclude static variables in several contexts35,36,37. However, NDVI was ultimately excluded from the final modeling framework, as explained in the Uncertainty section.

Climate and elevation data were obtained from WorldClim (v2.1), which provides 19 bioclimatic variables (Bio1–Bio19) and elevation data at a spatial resolution of 1/12°38. The dataset includes long-term historical climate averages for the period 1970–2000, as well as projected future climate averages at 20-year intervals from 2021 to 2100. WorldClim is an online database that provides global climate data, with version 2.1 being its second major update. This dataset, based on climate model projections, is widely used in biodiversity conservation, ecological modeling, climate change impact assessments, and agricultural planning38. The global climate dataset provides both historical climate data and future projections, covering four SSP–RCP scenarios and 10 GCMs. Slope data were derived from elevation using the ‘Slope Calculation’ function in ArcGIS Pro (v3.1.6). Global NDVI data were obtained from the PKU-GIMMS-NDVI dataset (v1.2) released by Peking University, at a resolution of 1/12° over the period 1982–202039. To align as closely as possible with the temporal coverage of the WorldClim climate data, we used the long-term mean for the period 1982–2000 as a proxy for average vegetation greenness during the baseline period. This dataset addresses uncertainties in existing long-term NDVI records, particularly those caused by NOAA satellite orbital drift and AVHRR sensor degradation and has demonstrated high accuracy when evaluated against Landsat NDVI samples39.

Ecological niche modeling of representative rodents

Ecological niche refers to the role or function of a species within its environment, encompassing its position in the ecosystem, interactions with other species (e.g., predation, competition), ecological requirements (e.g., food, habitat, climatic conditions), and the way it utilizes resource endowments and environmental conditions40,41. This study selected habitat preferences and environmental factors, such as temperature, humidity, and food availability (vegetation coverage), as input variables for ecological niche modeling. We employed the Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) algorithm within the species distribution modeling (SDM) framework to analyze the ecological niches of representative rodents, using Maximum Entropy Species Distribution Modeling software (v3.4.4).

MaxEnt is a machine-learning algorithm based on the maximum entropy method (see Eq. 1), integrating species occurrence data with environmental variables to predict potential species distributions42,43. The algorithm is advantageous due to its low data requirements, high predictive accuracy, and straightforward implementation, making it one of the most widely used SDMs in biogeography and macroecology44. The core principle of MaxEnt is to select the probability distribution with the highest entropy that satisfies the given constraints, thereby minimizing prediction risk. This ensures an accurate estimation of species distributions by producing the most uniform probability distribution possible in the absence of additional subjective assumptions, ultimately reducing predictive uncertainty. MaxEnt was trained using species occurrence records and randomly sampled background points. These background points are not considered true absences but are used to characterize the available environmental space, following standard practice in presence-only species distribution modeling42,44.

where X denotes the set of all spatial grid cells within the study area; xi represents the i-th known occurrence location of the species, with \(i\) = 1,2, …, \(n\); fj(x) is the \(j\)-th environmental feature function at location x; and p(x) is the estimated spatial probability distribution of species presence.

We conducted both historical and future distribution modeling for ten representative rodent genera. Variable selection and parameter optimization were necessary when performing ecological niche modeling using MaxEnt. To ensure methodological rigor, we reviewed multiple studies on rodent distributions and followed a systematic process25,45,46,47,48:

First, to reduce multicollinearity among variables, Pearson Correlation (r) was used to compute pairwise correlations among all variables. Meanwhile, all the preselected historical environmental variables were input into MaxEnt to obtain the Percent Contribution (PC) and Permutation Importance (PI) of each variable in influencing species distribution. The r, PC, and PI values obtained from the initial modeling of each Genus are shown in Fig. 3.

Environmental variable correlations and variables’ percent contributions and permutation importance for each genus in initial modeling. Bottom-left: Network diagram showing the percent contribution (%) of each environmental variable (positioned diagonally) to each rodent genus (along the left and bottom axes). The thickness and color of the connecting lines represent the magnitude of contribution, with thicker and more yellow edges indicating higher contribution. Center: Pearson correlation matrix among the 22 environmental variables used in the modeling. Right: Permutation importance (%) of each variable in predicting genus-level habitat suitability.

Then, according to the obtained r, PC, and PI values, we refined the environmental variable set by removing highly correlated variables (|r| ≥ 0.8), retaining those with a greater contribution for PC and PI to species distribution. The final selected environmental variables were then re-entered into MaxEnt (see Table 2) for parameter tuning using the ENMeval package in R. We tested regularization multiplier (RM) values ranging from 1.0 to 6.0 (with 0.5 steps), while keeping the feature classes at MaxEnt’s default “Auto features” setting. Model performance for each RM setting was evaluated using Area Under the Curve (AUC) and True Skill Statistic (TSS). The RM value yielding the best balance between predictive accuracy and generalization was selected for each genus (see Fig. 4).

Area Under the Curve (AUC) and True Skill Statistic (TSS) performance across varying regularization multipliers for (a) Akodon, (b) Apodemus, (c) Cricetulus, (d) Mastomys, (e) Microtus, (f) Mus, (g) Oligoryzomys, (h) Peromyscus, (i) Phyllotis, and (j) Rattus. All models were run with MaxEnt’s default “Auto features”. Each point represents the mean AUC and TSS across 25 replicate runs, with error bars indicating ± 1 standard deviation. Note: TSS was calculated using the Maximum Training Sensitivity Plus Specificity (MTSS) threshold applied to cloglog-transformed outputs.

Next, using the final set of environmental variables and the optimized parameters, we conducted 25 replicate runs for both historical and future distribution modeling of each species. Historical distribution modeling was based on historical-format environmental variables. Following the historical distribution modeling results, we selected 10 GCMs and their corresponding four SSP–RCP scenarios for future projections (Table 3 and Table 4). The MaxEnt parameter settings were as follows: randomseed, randomtestpoints = 25, maximumbackground = 100000, replicates = 25, replicatetype = bootstrap, writebackgroundpredictions, and maximumiterations = 5000.

Finally, we generated a global probability distribution dataset for rodents from 2021 to 2100 at 20-year intervals under four SSP–RCP scenarios and ten GCMs. The probability estimates were generated using cloglog transformation, which is considered to have stronger theoretical interpretability compared to the traditional logistic transformation28.

Data Records

The global rodent distribution projections under four SSP–RCP scenarios and 10 GCMs from 2021 to 2100 are stored in GeoTIFF format (.tif), using the WGS84 coordinate system at a 1/12° resolution. The dataset consists of 9,820 files, 340 GB, including historical/baseline data derived from 1970–2000 observations and future data from 2021–2100 projections. These files are publicly accessible on Figshare for Institutions (UCL) and can be downloaded49.

Technical Validation

Accuracy

To ensure the robustness and reliability of the rodent distribution models, we implemented a multi-layer evaluation framework that includes both continuous and binary performance metrics, parameter optimization, and replicated model fitting. These multiple layers of evaluation confirm the predictive strength of our models and the credibility of the modeling process.

We applied the random seed function to partition the occurrence dataset of each species into a training set (75%) and a testing set (25%). Model performance was evaluated using the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) and the area under the curve (AUC) values derived from the fitted results of each species (see Fig. 5). Previous studies have shown that an AUC value above 0.7–0.8 indicates relatively high model performance and reliability42,50. Our results demonstrate that the AUC values for all species exceeded 0.9, suggesting high model performance and confidence.

The species-specific receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves from the final model for (a) Akodon, (b) Apodemus, (c) Cricetulus, (d) Mastomys, (e) Microtus, (f) Mus, (g) Oligoryzomys, (h) Peromyscus, (i) Phyllotis, and (j) Rattus, Each curve represents the average ROC performance across 25 replicate runs. Note: Specificity is defined using predicted area (background extent), rather than true commission errors, in line with MaxEnt’s presence-only evaluation framework.

MaxEnt automatically generates multiple thresholds based on the modeling results and various threshold rules. By selecting an appropriate threshold, the continuous model output can be converted into a a binary prediction, classifying areas as suitable or unsuitable habitats. To evaluate the performance of these binary classifications, we calculated the True Skill Statistic (TSS), which considers both sensitivity and specificity and is not affected by prevalence, making it particularly suitable for presence-only models. We applied four commonly used thresholding rules to assess model accuracy under different classification criteria: (1) Equal Training Sensitivity and Specificity (ETSS), (2) Maximum Training Sensitivity plus Specificity (MTSS), (3) Balance Training Omission and Predicted Area (BTPT), and (4) Equate Entropy of Thresholded and Original Distributions (EETO). As shown in Table 5, the models exhibited consistently high binary classification accuracy across genera, with average TSS values generally exceeding 0.8 under most thresholding approaches.

Furthermore, to enhance model robustness, we performed parameter tuning in MaxEnt by testing a range of regularization multiplier (RM) values from 1.0 to 6.0 in 0.5 steps, while keeping the feature classes set to the default “Auto features” configuration. For each RM value, model performance was assessed using the mean AUC and TSS scores. As shown in Fig. 3, both AUC and TSS values generally declined with increasing RM, reflecting the trade-off between model complexity and predictive performance. Meanwhile, we observed that higher RM values tended to produce overly generalized suitability maps, with predicted distributions becoming more spatially diffuse and ecologically implausible. Based on these observations, we selected RM = 1.0 as the final setting for all genera. This conservative choice ensured a consistent balance between predictive performance and ecological interpretability.

Additionally, we conducted 25 replicate runs for each genus to obtain more robust results. Based on these 25 replicate runs, we generated descriptive statistics for species occurrence probability at each grid cell, including the maximum (max), minimum (min), median, 95% confidence interval (lowerci), average (avg), and standard deviation (stddev).

Uncertainty

Model uncertainty primarily stems from parameter settings, environmental variable selection, and sample data quality. Regarding parameter settings, key factors include the regularization multiplier, the number of background points, and the number of validation replicate runs. Our results indicate that adjustments to the regularization multiplier have minimal impact on the performance of this model. To illustrate, after modifying the regularization multiplier, the ROC curve and corresponding AUC values remained largely unchanged. We speculate that this insensitivity may be due to the large spatial scale of the model, which reduces the influence of regularization adjustments. In contrast, the number of background points has a more substantial effect on model performance. The background point quantity influences both model fitting and predictive accuracy. Specifically, too few background points may lead to insufficient sampling of environmental variables, preventing the model from accurately capturing the species’ ecological niche. Conversely, an excessive number of background points may introduce noise, leading to model overfitting. Research suggests that the number of background points should be proportional to the number of occurrence records (e.g., 10 times the number of presence records), and the optimal value should be adjusted based on the research species and data quality51. Other studies indicate that the accuracy of the MaxEnt algorithm improves as the number of background points increases; however, this improvement plateaus once a certain threshold is reached52. To be precise, model performance is optimized when the Number of Random Points (NRP) is several times the Number of Training Presences (NTP). For species with widespread distributions, using a large number of background points may be advantageous52. Considering these suggestions, we set the number of background points for each model to 100,000, taking into account the global grid scale and the sample sizes of representative rodents. Furthermore, to enhance model stability and robustness, we increased the number of validation replicate runs from the conventional 10 to 25 and removed occurrence records with missing environmental variable data.

Regarding environmental variable selection, multicollinearity among variables can contribute to model uncertainty and reduce predictive accuracy. To mitigate this, we evaluated Pearson correlation coefficients among environmental variables and reviewed the initial modeling results for each species to filter and select the final environmental variables for modeling. A particular case worth noting is the decision to exclude NDVI from the final variable set. NDVI was initially included in the candidate variable pool and participated in the initial modeling phase for all genera. However, it was excluded from the final models for three main reasons:

First, NDVI showed strong collinearity with Bio2 (Pearson r = 0.88), as illustrated in the variables’ correlation matrix (see Fig. 3, center panel), which raised concerns of redundancy.

Second, although NDVI showed non-negligible percent contribution in some genera (e.g., 10.5% in Cricetulus), its permutation importance—a more robust indicator of a variable’s independent effect on model performance—remained consistently low across all genera (maximum 3.2%, and < 2.1% in others), as shown in Fig. 3 (right panel). Percent contribution reflects the gain added by each variable during the iterative model fitting process and can be influenced by variable entry order and collinearity. In contrast, permutation importance measures the decrease in model performance when the values of a variable are randomly permuted, thus providing a more reliable assessment of its unique predictive value. The low permutation importance of NDVI suggests that its independent predictive value and added contribution to the model were limited.

Third, and most importantly, NDVI lacks scenario-consistent future projections under CMIP6, which limits its utility for long-term forecasting. Although we compared NDVI averages from 1982–2000 (used in baseline modeling) and 2001–2020 and found a high spatial correlation (r > 0.98), we also observed clear differences in vegetation intensity across many regions. This indicates potential risk when treating NDVI as a static environmental layers like elevation and slope in future-oriented projections.

Taken together, NDVI’s overlap in explanatory power with Bio2, the low independent contribution to model performance, the lack of usable future NDVI data, and its associated uncertainty led us to retain Bio2 and exclude NDVI from the final modeling framework. We believe this decision offers a practical balance between ecological relevance, temporal consistency, and model robustness.

For sample data quality, previous studies suggest that increasing the number of occurrence records enhances model stability53. Therefore, we thoroughly reviewed the species occurrence dataset from GBIF and corrected taxonomic misidentifications and synonyms, retaining as many valid occurrence points as possible to improve data accuracy. In addition, as the WorldClim v2.1 historical climate dataset only covers the period from 1970 to 2000, we restricted our modeling to occurrence records within this timeframe to ensure temporal consistency. In future work, we aim to explore the use of alternative climate datasets with coverage beyond 2000 (e.g., for 2000–2020), in combination with more recent species occurrence records, to support retrospective modeling (historical modeling) and validation.

Usage Notes

The GridScopeRodents dataset has a spatial resolution of 1/12° and uses the WGS 1984 coordinate reference system (EPSG:4326), covering 10 genera projections in historical four SSP–RCP scenarios and 10 global climate models (GCMs). It includes projection data at 20-year intervals from 2021 to 2100, as well as baseline data modeled using 1970–2000 records, comprising a total of 9,820 files with a combined size of 340 GB. In addition, a detailed summary of each genus’s ecological and economic relevance, with supporting literature, is provided in a supplementary table titled Rodent Genus Selection Justification (Literature). The dataset is publicly available via Figshare for Institutions (UCL)49.

All data are stored in GeoTIFF (.tif) format and can be accessed and processed using ArcGIS, ENVI, R, and Python. Each GeoTIFF file contains grid-based predictions of habitat suitability, with values ranging from 0 to 1. These values represent the probability of species presence at each grid cell, transformed using the cloglog output function in MaxEnt, which is approximately interpretable as the probability of occurrence under typical presence-only assumptions. A higher value indicates greater predicted environmental suitability for the species, while lower values suggest unsuitable or marginal areas. Users may interpret the continuous output directly, or apply threshold values (e.g., MTSS, ETSS) to convert the suitability layer into a binary presence/absence map. The thresholds used for evaluation in this dataset are provided in Table 5.

The dataset is organized into two main directories: historical_baseline and future. The historical_baseline folder follows the structure Genus_Statistics, while the future folder is organized as Genus_Statistics_Year_SSP-RCP. Notably, “historical” refers to distribution probabilities modeled using 1970–2000 data, serving as the baseline. Files in the historical_baseline folder follow the naming convention Genus_Statistics.tif, while those in the future folder use the format Genus_GCM_Year_SSP-RCP_Statistics.tif. Here, Genus represents the rodent genus, GCM denotes the global climate model used, Year specifies the projected time period, SSP-RCP indicates the shared socioeconomic pathway and representative concentration pathway, and Statistics describes the file’s data characteristics. For example, Akodon_ACCESS-CM2_2021–2040_ssp126_avg.tif represents the average projected occurrence probability for Akodon under the SSP1–RCP2.6 scenario and the ACCESS-CM2 global climate model during 2021–2040 over 25 replicate runs. To enhance the applicability of the results and reduce uncertainty arising from inter-model variability, we additionally provide ensemble-mean projections averaged across the ten global climate models (GCMs). These ensemble data products cover all SSP–RCP scenarios and future time slices (2030s, 2050s, 2070s, and 2090s). The ensemble-mean maps of each genus are stored in the GCM_Averaged_Projections subfolder within the future directory of the Figshare dataset named Genus_Year_SSP-RCP_GCM_Averaged.tif. Users seeking more generalized or policy-relevant distribution trends may find these averaged outputs preferable to projections from individual GCMs.@media print {.ms-editor-squiggler {display:none !important;}}.ms-editor-squiggler {all: initial;display: block !important;height: 0px !important;width: 0px !important;}

Code availability

This study utilized MaxEnt v3.4.454, the SDMtoolbox Pro extension for ArcGIS Pro (http://www.sdmtoolbox.org/), and the ENMeval package in R (via GitHub or CRAN) for data generation and processing. All these tools are freely available for download and use. Custom Python code for computing the TSS test from MaxEnt outputs is available via Figshare for Institutions (UCL)49.

References

Malhi, Y. et al. Climate change and ecosystems: Threats, opportunities and solutions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 375, 20190104, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0104 (2020).

Chapin III, F. et al. Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature 405, 234–242, https://doi.org/10.1038/35012241 (2000).

Montràs-Janer, T. et al. Anthropogenic climate and land-use change drive short- and long-term biodiversity shifts across taxa. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 739–751, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02326-7 (2024).

Bonan, G. B. Forests and climate change: Forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320, 1444–1449, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1155121 (2008).

Urban, M. C. Accelerating extinction risk from climate change. Science 348, 571–573, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa4984 (2015).

Newbold, T. et al. Tropical and Mediterranean biodiversity is disproportionately sensitive to land-use and climate change. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1630–1638, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-01303-0 (2020).

Hellmann, J. J. et al. Five potential consequences of climate change for invasive species. Conserv. Biol. 22, 534–543, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00951.x (2008).

Antão, L. H. et al. Climate change reshuffles northern species within their niches. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 587–592, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01381-x (2022).

Heikonen, S. et al. Climate change threatens crop diversity at low latitudes. Nat. Food. 6, 331–342, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-025-01135-w (2025).

Macdonald, D. W. The encyclopedia of mammals. Oxford University Press (2006).

Wood, B. J. & Singleton, G. R. Rodents in agriculture and forestry. in Rodent pests and their control (eds. Buckle, A. & Smith, R.) 33–80 https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845938178.0033 (CABI, UK, 2015).

Paini, D. R. et al. Global threat to agriculture from invasive species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113, 7575–7579, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602205113 (2016).

Lima, M., Marquet, P. A. & Jaksic, F. M. El Niño events, precipitation patterns, and rodent outbreaks are statistically associated in semiarid Chile. Ecography 22, 213–218, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.1999.tb00470.x (1999).

Zhang, Y. et al. Evolutionary and ecological patterns of scatter‐and larder‐hoarding behaviours in rodents. Ecol. Lett. 25, 1202–1214, https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13992 (2022).

Biancolini, D. et al. Global distribution of alien mammals under climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17560, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.17560 (2024).

World Health Organization. Plague (2022). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/plague (Accessed on 15 February 2025).

Klitting, R. et al. Predicting the evolution of the Lassa virus endemic area and population at risk over the next decades. Nat. Commun. 13, 5596, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33112-3 (2022).

Backhans, A. & Fellström, C. Rodents on pig and chicken farms – a potential threat to human and animal health. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiology 2, 17093, https://doi.org/10.3402/iee.v2i0.17093 (2012).

Bai, D. et al. Climate change and climate niche shift equally attribute to the northwest range expansion of Asian house rats under intensified human activities. Landscape Ecol 38, 3027–3044, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-023-01773-0 (2023).

Singleton, G. R. et al. Rodent management and cereal production in asia: Balancing food security and conservation. Pest Manag. Sci. 77, 4249–4261, https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.6462 (2021).

Wiens, J. A. et al. Niches, models, and climate change: Assessing the assumptions and uncertainties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 19729–19736, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901639106 (2009).

Menke, S. B. et al. Characterizing and predicting species distributions across environments and scales: Argentine ant occurrences in the eye of the beholder. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 18, 50–63, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2008.00420.x (2009).

Anderson, R. P. Harnessing the world’s biodiversity data: Promise and peril in ecological niche modeling of species distributions. Ann. Ny. Acad. Sci. 1260, 66–80, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06440.x (2012).

Melo-Merino, S. M., Reyes-Bonilla, H. & Lira-Noriega, A. Ecological niche models and species distribution models in marine environments: A literature review and spatial analysis of evidence. Ecol. Modell. 415, 108837, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2019.108837 (2020).

Araújo, M. B. et al. Standards for distribution models in biodiversity assessments. Sci. Adv. 5, eaat4858, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat4858 (2019).

Chauvier, Y. et al. Resolution in species distribution models shapes spatial patterns of plant multifaceted diversity. Ecography 2022, e05973, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.05973 (2022).

Elith, J. et al. Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29, 129–151, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2006.0906-7590.04596.x (2006).

Phillips, S. J. et al. Opening the black box: An open‐source release of maxent. Ecography 40, 887–893, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.03049 (2017).

Ahmadi, M. et al. MaxEnt brings comparable results when the input data are being completed; Model parameterization of four species distribution models. Ecol. Evol. 13, e9827, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9827 (2023).

GBIF.org. GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.py22zv (Accessed on 9 January 2025) (2025).

iNaturalist contributors. iNaturalist Research-grade Observations. iNaturalist.org. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/ab3s5x (Accessed via GBIF.org on 28 February 2025). Specific occurrences accessed: https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/4458607467, https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/5063061257, https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/2331954057, https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/2005257121, https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/5063973019, https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/4993917726, https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/4516811451, https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/4982181198, https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/5063135433 (2025).

Observation.org. Observation.org, Nature data from around the World. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/5nilie (Accessed via GBIF.org on 27 February 2025). Specific occurrences accessed: https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/4891235332 (2025).

Parviainen, M., Zimmermann, N. E., Heikkinen, R. K. & Luoto, M. Using unclassified continuous remote sensing data to improve distribution models of red-listed plant species. Biodivers. Conserv. 22, 1731–1754, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-013-0509-1 (2013).

Pettorelli, N. et al. Using the satellite-derived NDVI to assess ecological responses to environmental change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 503–510, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.011 (2005).

Stanton, J. C., Pearson, R. G., Horning, N., Ersts, P. & Reşit Akçakaya, H. Combining static and dynamic variables in species distribution models under climate change. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 349–357, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00157.x (2012).

Schwager, P. & Berg, C. Remote sensing variables improve species distribution models for alpine plant species. Basic Appl. Ecol. 54, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2021.04.002 (2021).

Wen, L., Saintilan, N., Yang, X., Hunter, S. & Mawer, D. MODIS NDVI based metrics improve habitat suitability modelling in fragmented patchy floodplains. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 1, 85–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsase.2015.08.001 (2015).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: New 1‐km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086 (2017).

Li, M. et al. Spatiotemporally consistent global dataset of the GIMMS normalized difference vegetation index (PKU GIMMS NDVI) from 1982 to 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 4181–4203, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-4181-2023 (2023).

Putman, R. J. & Wratten, S. D. The Concept of the Niche. In Principles of Ecology https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-6948-6_6 (Springer, Dordrecht, 1984).

Holt, R. D. Bringing the hutchinsonian niche into the 21st century: Ecological and evolutionary perspectives. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106, 19659–19665, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0905137106 (2009).

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P. & Schapire, R. E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Modell. 190, 231–259, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026 (2006).

Phillips, S. J., Dudík, M. & Schapire, R. E. A maximum entropy approach to species distribution modeling. in Twenty-first international conference on Machine learning - ICML ’04 83 https://doi.org/10.1145/1015330.1015412 (ACM Press, Banff, Alberta, Canada, 2004).

Elith, J. et al. A statistical explanation of MaxEnt for ecologists: Statistical explanation of MaxEnt. Divers. Distrib. 17, 43–57, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2010.00725.x (2011).

Widick, I. V. & Bean, W. T. Evaluating current and future range limits of an endangered, keystone rodent (dipodomys ingens). Divers. Distrib. 25, 1074–1087, https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12914 (2019).

Perkins-Taylor, I. E. & Frey, J. K. Predicting the distribution of a rare chipmunk (neotamias quadrivittatus oscuraensis): Comparing MaxEnt and occupancy models. J. Mammal. 101, 1035–1048, https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyaa057 (2020).

Pardi, M. I. et al. Testing climate tracking of montane rodent distributions over the past century within the great basin ecoregion. Global Ecol. Conserv. 24, e01238, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01238 (2020).

Lu, L. et al. Using remote sensing data and species–environmental matching model to predict the potential distribution of grassland rodents in the northern China. Remote Sens. 14, 2168, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14092168 (2022).

Lan, Y., et al. GridScopeRodents: High-Resolution Global Typical Rodents Distribution Projections from 2020 to 2100 under Diverse SSP-RCP Scenarios. https://doi.org/10.5522/04/28652219 (2025).

Swets, J. A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 240, 1285–1293, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3287615 (1988).

Whitford, A. M., Shipley, B. R. & McGuire, J. L. The influence of the number and distribution of background points in presence-background species distribution models. Ecol. Modell. 488, 110604, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2023.110604 (2024).

Liu, C., Newell, G. & White, M. The effect of sample size on the accuracy of species distribution models: considering both presences and pseudo-absences or background sites. Ecography 42, 535–548, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.03188 (2019).

Chen, X., & Lei, Y. Effects of sample size on accuracy and stability of species distribution models: A comparison of GARP and Maxent. In Z. Qian, L. Cao, W. Su, T. Wang, & H. Yang (Eds.), Recent Advances in Computer Science and Information Engineering (Vol. 125, pp. 661–666). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-25789-6_80 Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg (2012).

Phillips, S. J., Dudík, M. & Schapire, R. E. Maxent software for modeling species niches and distributions (Version 3.4.4). Available from http://biodiversityinformatics.amnh.org/open_source/maxent/ (Accessed on 16 October 2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [72522016, 72274011, and 72021001]. The authors thank Lei Zhao at the State Key Laboratory of Regional and Urban Ecology, Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences for his guidance on model development. The authors also thank Yang Zhao at the Bartlett School of Planning, University College London for her assistance with data management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L.: Methodology, Software, Data Curation, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. X.W.: Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Visualization. M.X.: Validation, Writing - Review & Editing. K.L.: Data Curation, Resources. Y.H.: Writing - Review & Editing. G.Z.: Writing - Review & Editing. F.L.: Writing - Review & Editing. W.S.: Writing - Review & Editing. R.Z: Resources. Y.X.: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

We declare that the authors have no competing interests as defined by Nature Research, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lan, Y., Wu, X., Xu, M. et al. High-resolution global distribution projections of 10 rodent genera under diverse SSP-RCP scenarios, 2021–2100. Sci Data 12, 1467 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05793-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05793-0