Abstract

Scientists have investigated the thermal tolerance of organisms for centuries, yet the field has not lost relevance as the environmental threats of thermal pollution and global change sharpen the need to understand the thermal vulnerability of organisms in landscapes increasingly subjected to multiple stressors. Freshwater fish and invertebrates are greatly underrepresented in recent large-scale compilations of thermal tolerance, despite the importance of freshwaters as a crucial resource and as havens for biodiversity. Therefore we compiled ThermoFresh, a thermal tolerance database for these organisms that includes literature from 1900 until the present, sourced from five languages to counteract geographic bias. The database contains over 6800 records for over 900 species, including 470 invertebrates, as well as 505 thermal tolerance tests conducted with additional stressors present. We provide a valuable resource to test hypotheses on thermal risks to freshwater organisms in present and future environments subject to multiple stressors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Thermal limits of life have interested researchers since at least the 1700s1,2,3,4,5, with early comparisons of thermal tolerances between organisms published in the late 1800s3. Despite the large volume of research on the biological and ecological influence of temperature in the last two centuries, many questions regarding thermal tolerances remain unanswered6,7,8. For example, the relationship between oxygen and thermal tolerance is still contested9,10, and the influence of thermal tolerance on range limits not fully understood11,12. The evolutionary determinants of thermal tolerance continue to engage contemporary research13,14,15,16,17.

Furthermore, thermal tolerance can be measured in different ways, complicating large-scale comparisons18,19,20,21,22. Two fundamental methodologies have emerged to measure thermal tolerance of a species in the last century. One method involves ramping the temperature until a specified endpoint is reached, known as the critical thermal method, coined by Cowles and Bogert in 194423, though similar methods existed previously24,25. The metrics for upper and lower thermal tolerance are known as critical thermal maximum (CTmax) and critical thermal minimum (CTmin), respectively, which represent the upper and lower bounds of a thermal performance curve26,27,28. The most commonly measured endpoint for this method is the loss of equilibrium, which represents a temperature at which an organism can no longer escape conditions that would lead to death; however, the organism should be able to recover once removed from the test19,29. This method has gained popularity over time, as the test can be conducted quickly, without permanently harming the organisms, repeatedly on the same organism, and with a small sample of test organisms29. Modern mobile heating units allow this methodology to be conducted in the field30,31. The lethal thermal maximum (LTmax) or lethal thermal minimum (LTmin) metrics are reached when the temperature is ramped until death occurs32. The second method is a static assay, wherein groups of organisms are kept at a fixed temperature for a fixed period of time. This method was formally named the incipient lethal method by Fry in 194733, based on work by others in the two decades prior34,35,36,37,38. Percentage mortality is assessed as an endpoint for each group, and statistical methods such as probit analysis used to evaluate the temperature at which a certain percentage of the group is affected37. The LT50 metric is the temperature at which 50% of the organisms perish, analogous to the LC50 of ecotoxicological assays for chemicals33,39. As with LC50 metrics, LT50 metrics are commonly measured at 24, 48, or 96 hours18. The incipient upper or lower lethal temperature (IULT and ILLT, respectively) is a metric distinguished from the LT50 by the longer time course of the test – the IULT represents the temperature which is not fatal to 50% of a population irrespective of exposure time34. This method has decreased in relative popularity over time, due to the large amount of resources required29. A few studies have compared these two metrics on a theoretical40,41 or empirical42 level, but with limited sample sizes.

A third method known as the thermal death time (TDT) was developed concurrently with the critical thermal and incipient lethal temperature methods. This method observes the time elapsed until an endpoint (usually death) occurs at constant temperatures. The role of time in temperature tolerance has been acknowledged since the 1940s, notably by Fry during the development of the incipient lethal temperature procedure25,34,43. Recent works have unified thermal tolerance methodologies by considering tolerance in the context of intensity and duration of exposure40,41,44,45,46. Thermal death time studies fall outside of the scope of the present study, as the TDT metric (time) does not directly match the temperature metric of the other methodologies. While mathematical models could resolve this discrepancy40,44,45, the present work includes only reported metrics that can be tracked to a primary source.

With the advanced understanding of climate change effects, large collections of thermal limits have been compiled to assess the vulnerability of organisms to warming on a global scale and to answer fundamental questions on the determinants of thermal tolerance47,48,49,50,51,52. Freshwater taxa are not well-represented within these collections, with the exception of amphibians47,52,53,54. Freshwaters support disproportionately high levels of biodiversity and provide vital resources for people55. Freshwater ecosystems, including rivers, lake, and wetlands, cover approximately 3% of Earth’s surface but provide habitats for over 50% of all described fish species and a third of all known vertebrates56,57. In addition, these systems provide services such as drinking water, water purification, and contribute to climate regulation. Freshwater ecosystems are directly threatened by global warming on a large scale, and locally by thermal pollution from industrial effluents58,59,60. Moreover, climate change may also indirectly increase water temperatures. For example, flow intermittence induced by climatic changes may indirectly result in strongly increased water temperatures6,61. Other stressors, such as hydromorphological changes and removal of riparian vegetation can also be associated with increased water temperature6,62,63. Evaluating the effects of increasing temperatures on biodiversity requires information on species’ thermal tolerance. Hence, we established the ThermoFresh database focusing on the thermal tolerance of freshwater taxa, which allows for intra- and interspecific comparisons among global freshwater assemblages, assessment of thermal vulnerability under warming scenarios, and prediction of future range shifts.

Thermal tolerance can also change in the presence of other stressors53,64, which affect its ecological relevance in a world where many organisms are increasingly subjected to multiple stressors58,65. We include thermal tolerance tests in the presence of additional stressors, with information on the type and level of the stressor(s). This facilitates future use of the database in disentangling complex interactions between multiple stressors and consequential effects on organisms in stressful environments.

The database was developed following current recommendations of best practice66,67,68. In comparison to previous studies we aimed to reduce geographic bias, provide multiple records per species (where possible, to allow assessment of intraspecific variation), and report measures of dispersion, to address gaps identified in recent literature7,54. We have included thermal tolerance metrics determined from the critical thermal method or the incipient lethal method, including those conducted on the same species within the same study42,69, which facilitates comparison of how the metrics are related across taxonomic groups. Our database focuses on freshwater fish and invertebrates, with records collated from previous compilations and expanded with new literature searches, including in widely spoken languages other than English. Including widely spoken non-English languages in ecological literature searches decreases geographical bias, which is critical for extrapolating results across the diverse regions of the earth70,71. The current uncertainty induced by geographical bias in physiological data overrides the uncertainty in future climate predictions72, and non-English literature can help counteract such bias73,74,75. Additionally, the publication rate of non-English studies on biodiversity is growing in many countries76. The relevance of non-English literature has been increasingly recognized70,71,73.

Methods

Workflow

The conceptualization of the database started with two previous compilations, the GlobTherm database and a study by Leiva and colleagues47,52. The search terms used in these studies were implemented in scoping searches, during which two additional compilations, authored by Cereja53 and Sundermann and colleagues77, respectively, were found. These four recently published databases were initially selected based on their size, freshwater taxa inclusion, and date of publication. The reasons for the inclusion or exclusion of previous databases are listed in Table 1. To cover gaps in previous publications, we conducted searches in Chinese, German, French, and Spanish up until April 2023, and searches in English until April 2023 in Web of Science as well as from 2019 until April 2023 in Google Scholar. English search terms are listed in Table 2, and all search terms in Supplementary Table 1. During the searches it became apparent that invertebrates were severely underrepresented compared to fish. Therefore, we exerted additional search effort to increase the coverage of invertebrates in the database, using taxonomic names of common invertebrates in the search terms. Throughout this study, several additional compilations51,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87 were discovered, most newly published (Table 1). Of these, four were selected, then harmonized and added to the database following the same procedure as before. The complete workflow is visualized in Fig. 1.

Inclusion criteria

The database includes studies that fulfill three primary criteria: 1) report at least one thermal tolerance metric for an organism, 2) have mortality or a sublethal indication of imminent mortality (such as loss of equilibrium, loss of righting response, or onset of spasms) as an endpoint, and 3) test organisms are fish or invertebrates residing in fresh or brackish water habitats for at least part of their life cycle (Fig. 1). Studies that contained incomprehensible or missing methodology for thermal tolerance tests were excluded; minor methodological inconsistencies were noted during data extraction. The thermal tolerance metrics considered for inclusion needed to represent the result of either a dynamic or static assay, and either contain enough methodological information to deduce which kind of assay was conducted or cite the recognized metric name (CTmax, CTmin, LTmax, LTmin, LT50, IULT, ILLT) in accordance with literature describing methodology (notably key papers such as Cowles and Bogert 1944, Becker and Genoway 1979, Lutterschmidt and Hutchinson 1997, Beitinger and Bennett 2000)18,19,23,29.

Previous databases

We initially selected four recently published databases on thermal tolerance that include freshwater organisms and contain variables relevant to the test organisms and the test metrics. These were identified via scoping searches on thermal tolerance literature. The GlobTherm database47 contains thermal tolerance records for the largest number of species in one compilation to date, the compilation of Leiva and colleagues52 includes a high proportion of freshwater invertebrate taxa, the compilation by Cereja53 includes only aquatic species (therefore more freshwater taxa) and notes additional stressors53, and the dataset by Sundermann and colleagues77 focuses exclusively on freshwater invertebrates. Other large datasets either contained fewer relevant variables due to the nature of the research questions they were collected for51,88, fewer freshwater taxa (especially invertebrates)54,89, or a high duplication of studies with the selected databases90,91. We excluded collections published before 2018, given the high duplication with more recent literature (Table 1).

We attempted to harmonize the selected databases. However, previous databases either only reported one value per taxon, even when multiple values were reported in constituent studies, mislabelled thermal tolerance metrics (i.e. labelling all thermal tolerance values as CTmax, though some were other metrics), or lacked key information related to the method, location, or test organism. Thus all selected databases were filtered for relevant freshwater or brackish taxa, all existing data for these taxa combined, and each corresponding source reference examined to cross-check existing data, correct errors, and fill in missing variables. This included extracting additional data from the main text, tables, figures, and supplementary information of source studies. Additional records were added when present in the original source. When data was only presented in figures, it was extracted using Plot Digitizer92. Collected variables are summarized in Table 3, and the extraction protocol with descriptions of all variables in detail is available in the “methods” folder on GitHub (https://github.com/hsbayat/ThermoFresh/tree/main/methods; see also Code Availability section).

Four additional large collections were identified during and after the search and data extraction process (Table 1). The compilation by Dahlke and colleagues81 focuses on fish, including many sources from the grey literature, and all papers compiled by Comte & Olden 201784. Collections by Morley and colleagues51, Pottier and colleagues82, and Sasaki and colleagues83 all include invertebrates as well as fish. These were filtered for freshwater taxa and screened for duplicate sources; then data was extracted from each original source as described above.

Literature searches

We complemented the selection of records from existing compilations with new literature searches. A general literature search was conducted in Google Scholar in English for the time period from January 1, 2019 until April 26, 2023, to cover studies that appeared after the previous databases were compiled, with search terms targeting both the critical thermal and incipient lethal methodology (Table 2). Far more studies were obtained using search terms targeting the critical thermal method than those targeting the incipient lethal temperature. We concentrated search efforts on upper thermal tolerance, but also extracted lower thermal tolerance where it was reported. We also conducted a search in Web of Science from the earliest index date until April 26, 2023. Pilot searches were conducted in all languages to fine-tune the search terms. Final searches in French, German, and Spanish were conducted in Google Scholar, and the search in Chinese was conducted in the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), for the earliest indexed studies up until April 26, 2023 (Supplementary Table 1). The pilot search and search term refinement for the Spanish search were performed in the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciElo) and Google Scholar. More relevant publications were indexed in Google Scholar, so the final search was conducted there. Pilot searches in Italian and Norwegian did not result in any relevant publications. One publication in Danish came up as part of the English search and was included. Papers in other languages were excluded.

Fish made up the majority of freshwater taxa in existing databases, while invertebrates were vastly underrepresented47. The GlobTherm database containing the most taxa (over 2000) includes only 8 species of freshwater insects47, a four-fold underrepresentation according to current estimates of the total species on earth93,94. Therefore we exerted additional effort to find papers focused on the thermal tolerance of freshwater invertebrates. We deemed this extra effort unnecessary for fish, since freshwater fish were already well-represented in existing collections, with the large compilation by Dahlke and colleagues focusing on fish entirely. Freshwater invertebrate species outnumber freshwater fish at least seven to one; freshwater insect species alone outnumber freshwater fish species five to one95, yet fish species outnumber invertebrate species in all existing collections covering both groups.

Scoping searches confirmed that key papers focused on invertebrates were partly missed in searches with general search terms. We then modified the general English search terms by adding the order, family, or genus name of freshwater invertebrates obtained from a list of freshwater invertebrates sampled in Germany over the last 12 years, spanning habitats from near-natural to highly degraded conditions96,97. The orders and families from this list are distributed globally56, and contain many of the most studied taxa. Papers resulting from these searches were not limited to one geographic region. Nonetheless we expanded the search to include global invertebrate families from Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America98,99. A full list of all taxonomic names used in the search is found in the “methods” folder on GitHub (see Code Availability section). The expanded search resulted in 6 additional eligible studies, compared to 67 resulting from the initial list.

Google Scholar search results were saved as a file using Publish or Perish v8 software100. Search results were screened first for relevance by title and abstract, then for duplicates with the studies already included from previous databases. Some studies were eliminated during the data extraction phase because inclusion criteria were not met, in these cases the reason for elimination was noted.

Data extraction and processing

Data was extracted according to a standardized protocol. Following data extraction, a subset of the data was cross-checked against the source references by three authors. Data was also examined for outliers and unreasonable values indicative of errors (for instance, a weight of 2 kilograms for invertebrate larvae was reported, which was caused by a missed decimal point) were corrected. Spelling errors were also checked and corrected. The endpoint was scored variably by different authors, though it was often essentially the same. These were unified into simpler categories and details relegated to the notes. All categorical variables were examined and corrected for consistency; all variables and their categories are described in the full metadata on GitHub (https://github.com/hsbayat/ThermoFresh/tree/main/data/metadata). Once datasets from all authors were compiled and errors checked, coordinates were used to query the Köppen-Geiger climate region101, elevation, continent, and country of each sampling location. Missing values, primarily due to coastal proximity, were entered manually. Full taxonomic information for each taxon was queried from the Open Tree of Life102, which collates taxonomic information from multiple sources. To do this, Open Tree Taxonomy (OTT) identifiers were queried for all taxa names in the database, then taxonomic classifications were added for each taxon using the OTT identifier. All screening, harmonization, data processing, querying, and plotting were conducted in R v4.3.3103 with the following packages: revtools v0.4.1104, tidyverse v2.0.0105, data.table v1.14.10106, rotl v3.1.0107, taxize v0.9.100108, sf v1.0-15109, elevatr v0.99.0110, geodata v0.5-9111, terra v1.7-65112, fs v1.6.3113 rnaturalearth v1.0.1114, viridis v0.6.5115, patchwork v1.2.0116, ggridges v0.5.6117.

Data Records

ThermoFresh is split into four tables: thermal tolerance test information, reference information, taxonomic information, and location information. A combined table with all data, and code to combine them, is available on GitHub (https://github.com/hsbayat/ThermoFresh). Code and data are also available at Zenodo118. Full metadata is available in the “metadata” subfolder in the GitHub repository. All data files in the repository are saved as comma-separated values files (.csv). Reference information, including DOI where available, is provided in the reference table (thermtol_reference_final_ch.csv) as well as for each record in the combined table (thermtol_comb_final.csv). Reference information in the original language is also provided.

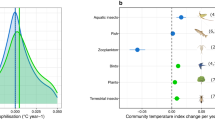

The database includes 6825 records for a total of 931 taxa, 470 invertebrates and 461 fish, from 1082 locations worldwide (Fig. 2). The database contains primarily organisms identified to the species level, with 86 taxa at the genus level and 8 above the genus level. Of the 931 total taxa, 666 reside solely in freshwater, 73 only in brackish waters, and 192 in both. A total of 505 tests recorded thermal tolerance of species in the presence of an additional stressor (e.g., pollutants, pathogen, reduced oxygen, flow velocity, salinity). The inclusion of variables like body size, life stage, coordinates, and environmental conditions allows for a wide range of hypotheses to be tested with this data. The detailed information on test metrics and methodology allows for metrics to be compared; Fig. 3 illustrates the density distributions for each metric. Records can be filtered according to desired features, e.g. a high or low acclimation temperature. Thermal tolerances from different climates can also be compared (Fig. 4a). Non-English languages account for 620 records, with 323 Chinese, 235 Spanish, 34 French, 21 German, and 7 Danish records. Non-English studies contributed most to records tested in arid climates, followed by temperate, tropical, and continental (Fig. 4b). The database features records from 1900 until 2023, which presents the opportunity for comparisons across time, though these may be limited by the scarcity of early data (Fig. 5).

A comparison of the density distributions of thermal tolerance values in the database for each metric. The points underneath each curve represent the sample size; with n = 460, 409, 692, 4362, 172, 83, 94, and 553 from top to bottom (upper other, upper LTmax, upper LT50, upper CTmax, lower other, lower LTmin, lower LT50, and lower CTmin, respectively). The fill color indicates the tolerance value in degrees Celsius.

Technical Validation

Data was extracted from the original literature sources for all studies resulting from literature searches; a note was made when data was found in supplementary information or extracted with Plot Digitizer92. Data was cross-checked with the original study for each record obtained from previous databases. A manual double-check of data entry with reference to the original source was done for 20.8% of all records by at least one additional person. Additionally the distributions of all numerical variables was visualized in R103, and outliers were manually checked. Outliers were defined as values exceeding 1.5 times the interquartile range above and below the first and third quartiles. Typos in taxon names were corrected, and outdated species names changed to currently accepted names (as of July 2024 in the Open Tree of Life Taxonomy). The names as referred to in the original source are in the notes column, where names were changed. The OTT identifier, which is included as a variable, allows for names to be updated more easily should they change in the future.

All records include a taxon name at the genus or species level, the origin of the test taxon, a thermal tolerance measure, the metric (indicating which methodology was used), the endpoint, the habitat, the location of sampling (or laboratory location for non-wild organisms), variables relating to the location (continent, country, elevation), and reference information (including publication year and language). Over 90% of records include sample size, acclimation information, and the life stage of the organism at the time of the test. Error measures are included for 65% of records; the type of error measure is also noted in all cases where error is included. This information, or lack thereof, can be used to filter the data as needed to investigate various research questions. The variables describing test methods (ramp, duration) allow for integration of the tolerance metrics into mathematical models of the tolerance landscape framework41,44,45. These contextualize tolerance with respect to intensity and duration of thermal stress, and enable extrapolation to field conditions119.

The multi-faceted search strategy involving harmonization of previous literature, additional literature searches in multiple languages across three search platforms (Google Scholar, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Web of Science), produced a comparably comprehensive compilation of thermal tolerance for freshwater invertebrates and fish. The concentrated search effort added 299 invertebrate taxa, nearly double the 171 taxa obtained from existing databases. Of 470 freshwater or brackish invertebrates, 322 are insects, representing 0.4% of the currently estimated total number of species93,95. While this may seem low, it is several hundred to thousand-fold more than previous work focused on all taxa47,52,53. The 461 freshwater fish species in the database represent 3% of the currently estimated number of species95.

While we attempted to counteract geographic bias in our approach, Europe and North America represent 65.6% of total records in the database though they make up 23.7% of Earth’s land area. With only English studies included, they would make up 70% of the records. While non-English languages contribute to lessening data gaps (Fig. 2), considerable work remains to fill large gaps in the geographic distribution of data.

When it comes to data gaps, multiple factors, including political ones, are at play. Data may simply be absent from certain areas, due to a lack of access, interest, or resources. In these areas more research and resources are needed to increase data coverage. However, data may also be locked in older studies which are much more difficult to access than more recently published work. For instance, thermal tolerance papers concerned with the deleterious effects of thermal effluents from power plants were prevalent in the time period from 1960 to 1980. While scans of these are common in US archives that are indexed by Google Scholar, the archives of other countries, which almost certainly also had research programs on the topic120, are difficult or impossible to access for non-native researchers. Screening literature in non-English languages requires resources, skill, and collaboration, but can play a key role in countering bias and harnessing information from locations that are least covered.

Given the continual increase in volume of literature on thermal tolerance (Fig. 5), on par with scientific research as a whole121, we expect our work to benefit from an update in the future. The search terms provided can be used to conduct equivalent searches and expand the database. Advances in automated data extraction122,123,124,125 foretell the automation of data synthesis research, which can enhance efforts to update synthetic work amidst ever-increasing output. So far, full automation of data extraction has been conducted for only few ecological variables122 or in medical research123,124,125. Medical research enforces stringent reporting guidelines for individual studies, which assist data synthesis and allow automated methods to operate effectively. Reporting guidelines have also been introduced for terrestrial respirometry126, climate change genomics127, and landscape ecology128, but have yet to be developed for thermal tolerance studies. A well-curated database such as ours can serve as a reference, benchmark, and training tool in future efforts to continuously synthesize new information on freshwater thermal tolerance.

Code availability

The code to process and aggregate the data and reproduce all figures is available on GitHub: https://github.com/hsbayat/ThermoFresh. The “methods” folder contains the data extraction protocol and additional methodological information.

References

Spallanzani. Opuscules de Physique, Animale et Vegetale. (Chez Barthelemi Chirol, Geneva, 1777).

Plateau, F. Recherches physico-chimiques sur les articules aquatiques. (F. Hayez, Imprimeur de l’Acadamie Royale de Belgique, Brussels, 1870).

Davenport, C. B. & Castle, W. E. Acclimatization of Organisms to High Temperatures 1) (1895).

Davy, J. Some Observations on the Ova of the Salmon, in relation to the distribution of Species (1855).

Hoppe-Seyler, F. Ueber die obere Temperaturgrenze des Lebens. Arch. Für Gesammte Physiol. Menschen Thiere 11, 113–121 (1875).

Desforges, J. E. et al. The ecological relevance of critical thermal maxima methodology for fishes. J. Fish Biol. 102, 1000–1016 (2023).

Herrando-Pérez, S., Vieites, D. R. & Araújo, M. B. Novel physiological data needed for progress in global change ecology. Basic Appl. Ecol. 67, 32–47 (2023).

Chown, S. L. Macrophysiology for decision-making. J. Zool. 319, 1–22 (2023).

Jutfelt, F. et al. Oxygen-and capacity-limited thermal tolerance: blurring ecology and physiology, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.169615 (2018).

Verberk, W. C. E. P. et al. Does oxygen limit thermal tolerance in arthropods? A critical review of current evidence. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. -Part Mol. Integr. Physiol. 192, 64–78 (2016).

Camacho, A. et al. Does heat tolerance actually predict animals’ geographic thermal limits? Sci. Total Environ. 917, 170165 (2024).

Gouveia, S. F. et al. Climatic niche at physiological and macroecological scales: the thermal tolerance–geographical range interface and niche dimensionality. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 23, 446–456 (2014).

Gutiérrez-Pesquera, L. M. et al. Testing the climate variability hypothesis in thermal tolerance limits of tropical and temperate tadpoles. J. Biogeogr. 43, 1166–1178 (2016).

Comte, L. & Olden, J. D. Evolutionary and environmental determinants of freshwater fish thermal tolerance and plasticity. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 728–736 (2017).

Perez, T. M. & Feeley, K. J. Weak phylogenetic and climatic signals in plant heat tolerance. J. Biogeogr. 48, 91–100 (2021).

Kellermann, V. et al. Upper thermal limits of Drosophila are linked to species distributions and strongly constrained phylogenetically. 109, 16228–16233 (2012).

Bodensteiner, B. L. et al. Thermal adaptation revisited: How conserved are thermal traits of reptiles and amphibians? J. Exp. Zool. Part Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 335, 173–194 (2021).

Beitinger, T. L., Bennett, W. A. & Mccauley, R. W. Temperature tolerances of North American freshwater fishes exposed to dynamic changes in temperature. Environ. Biol. Fishes 58, 237–275 (2000).

Becker, C. D. & Genoway, R. G. Evaluation of the critical thermal maximum for determining thermal tolerance of freshwater fish. Env Biol Fish 4, 245–256 (1979).

Lutterschmidt, W. I. & Hutchison, V. H. The critical thermal maximum: data to support the onset of spasms as the definitive end point. Can. J. Zool. 75, 1553–1560 (1997).

Golovanov, V. K. Influence of various factors on upper lethal temperature (review). Inland Water Biol. 5, 105–112 (2012).

Bates, A. E. & Morley, S. A. Interpreting empirical estimates of experimentally derived physiological and biological thermal limits in ectotherms 1. Can. J. Zool. 98, 237–244 (2019).

Cowles, R. B. & Bogert, C. M. A preliminary study of the thermal requirements of desert reptiles. Bull. AMNH 83 (1944).

Huntsman, A. G. & Sparks, M. I. No. 6: Limiting Factors For Marine Animals.: 3. Relative Resistance To High Temperatures. Contrib. Can. Biol. Fish. 2, 95–114 (1924).

Doudoroff, P. The resistance and acclimatization of marine fishes to temperature changes. i. Experiments with Girella nigricans (ayres). Biol. Bull. 83, 219–244 (1942).

Rezende, E. L. & Bozinovic, F. Thermal performance across levels of biological organization, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0549 (2019).

Clusella-Trullas, S., Garcia, R. A., Terblanche, J. S. & Hoffmann, A. A. How useful are thermal vulnerability indices? 36 (2021).

Huey, R. B. & Stevenson, R. D. Integrating Thermal Physiology and Ecology of Ectotherms: A Discussion of Approaches. Am. Zool. 19, 357–366 (1979).

Lutterschmidt, W. I. & Hutchison, V. H. The critical thermal maximum: history and critique. Can. J. Zool. 75, 1561–1574 (1997).

Garcia-Robledo, C., Kuprewicz, E. K., Dierick, D., Hurley, S. & Langevin, A. The affordable laboratory of climate change: devices to estimate ectotherm vital rates under projected global warming. Ecosphere 11, e03083 (2020).

Gilbert, M. J. H. et al. The thermal limits of cardiorespiratory performance in anadromous Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus): a field-based investigation using a remote mobile laboratory. Conserv. Physiol. 8, coaa036 (2020).

Chatterjee, N., Pal, A. K., Manush, S. M., Das, T. & Mukherjee, S. C. Thermal tolerance and oxygen consumption of Labeo rohita and Cyprinus carpio early fingerlings acclimated to three different temperatures. J. Therm. Biol. 29, 265–270 (2004).

Fry, F. E. J. Effects of the environment on animal activity. Publ Fish Res Lab 55, 1–62 (1947).

Fry, F. E. J., Hart, J. S. & Walker, K. F. Lethal temperature relations for a sample of young speckled trout. Univ. Tor. Stud. Biol. Ser. 54, 9–35 (1946).

Fry, F. E. J., Brett, J. R. & Clawson, G. H. Lethal limits of temperature for young goldfish. Rev Can Biol 1, 50–56 (1942).

Hathaway, E. S. Quantitative Study of the Changes Produced by Acclimatization in the Tolerance of High Temperatures by Fishes and Amphibians. vol. 1030 (US Government Printing Office, 1927).

Bliss, C. I. The Calculation of the Dosage-Mortality Curve. Ann. Appl. Biol. 22, 134–167 (1935).

Bliss, C. I. & Stevens, W. L. The Calculation of the Time-Mortality Curve. Ann. Appl. Biol. 24, 815–852 (1937).

Brett, J. R. Some lethal temperature relations of Algonquin Park fishes. (1944).

Cooper, B. S., Williams, B. H. & Angilletta, M. J. Unifying indices of heat tolerance in ectotherms. J. Therm. Biol. 33, 320–323 (2008).

Jørgensen, L. B., Malte, H., Ørsted, M., Klahn, N. A. & Overgaard, J. A unifying model to estimate thermal tolerance limits in ectotherms across static, dynamic and fluctuating exposures to thermal stress. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–14 (2021). 2021 111.

Dallas, H. F. & Ketley, Z. A. Upper thermal limits of aquatic macroinvertebrates: Comparing critical thermal maxima with 96-LT50 values. J. Therm. Biol. 36, 322–327 (2011).

Doudoroff, P. The resistance and acclimatization of marine fishes to temperature changes. ii. Experiments with Fundulus and Atherinops. Biol. Bull. 88, 194–206 (1945).

Rezende, E. L., Castañeda, L. E. & Santos, M. Tolerance landscapes in thermal ecology. Funct. Ecol. 28, 799–809 (2014).

Ørsted, M., Jørgensen, L. B. & Overgaard, J. Finding the right thermal limit: a framework to reconcile ecological, physiological and methodological aspects of CTmax in ectotherms. J. Exp. Biol. 225, jeb244514 (2022).

Semsar-kazerouni, M. & Verberk, W. C. E. P. It’s about time: Linkages between heat tolerance, thermal acclimation and metabolic rate at different temporal scales in the freshwater amphipod Gammarus fossarum Koch, 1836. J. Therm. Biol. 75, 31–37 (2018).

Bennett, J. M. Data Descriptor: GlobTherm, a global database on thermal tolerances for aquatic and terrestrial organisms Background & Summary. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.22 (2018).

Bennett, J. M. et al. The evolution of critical thermal limits of life on Earth. Nat. Commun. 12, 1198 (2021).

Sunday, J. M., Bates, A. E. & Dulvy, N. K. Thermal tolerance and the global redistribution of animals. Nat. Clim. Change 2012 29(2), 686–690 (2012).

Comte, L., Murienne, J. & Grenouillet, G. Species traits and phylogenetic conservatism of climate-induced range shifts in stream fishes. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–9 (2014).

Morley, S. A., Peck, L. S., Sunday, J. M., Heiser, S. & Bates, A. E. Physiological acclimation and persistence of ectothermic species under extreme heat events. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 28, 1018–1037 (2019).

Leiva, F. P., Calosi, P. & Verberk, W. C. E. P. Scaling of thermal tolerance with body mass and genome size in ectotherms: a comparison between water-and air-breathers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 374 (2019).

Cereja, R. Critical thermal maxima in aquatic ectotherms. Ecol. Indic. 119 (2020).

Pottier, P. et al. A comprehensive database of amphibian heat tolerance. Sci. Data 9, 600 (2022).

Lynch, A. J. et al. People need freshwater biodiversity. WIREs Water 10, e1633 (2023).

Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8259-7 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2008).

Carrete Vega, G. & Wiens, J. J. Why are there so few fish in the sea? Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 279, 2323–2329 (2012).

Jackson, M. C., Loewen, C. J. G., Vinebrooke, R. D. & Chimimba, C. T. Net effects of multiple stressors in freshwater ecosystems: a meta-analysis.

Coutant, C. C. & Brook, A. J. Biological aspects of thermal pollution I. Entrainment and discharge canal effects∗. C R C Crit. Rev. Environ. Control 1, 341–381 (1970).

Coutant, C. C. & Goodyear, C. P. Thermal Effects. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 44, 1250–1294 (1972).

Chiu, M.-C., Leigh, C., Mazor, R., Cid, N. & Resh, V. Chapter 5.1 - Anthropogenic Threats to Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams. in Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams (eds. Datry, T., Bonada, N. & Boulton, A.) 433–454, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803835-2.00017-6 (Academic Press, 2017).

Garner, G., Malcolm, I. A., Sadler, J. P. & Hannah, D. M. The role of riparian vegetation density, channel orientation and water velocity in determining river temperature dynamics. J. Hydrol. 553, 471–485 (2017).

Johnson, R. K. & Almlöf, K. Adapting boreal streams to climate change: effects of riparian vegetation on water temperature and biological assemblages. Freshw. Sci. 35, 984–997 (2016).

Cuenca Cambronero, M., Beasley, J., Kissane, S. & Orsini, L. Evolution of thermal tolerance in multifarious environments. Mol. Ecol. 27, 4529–4541 (2018).

Spence, A. R. & Tingley, M. W. The challenge of novel abiotic conditions for species undergoing climate-induced range shifts. Ecography 43, 1571–1590 (2020).

Schwanz, L. E. et al. Best practices for building and curating databases for comparative analyses. J. Exp. Biol. 225, jeb243295 (2022).

Mengist, W., Soromessa, T. & Legese, G. Method for conducting systematic literature review and meta-analysis for environmental science research. MethodsX 7 (2020).

O’dea, R. E. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses in ecology and evolutionary biology: a PRISMA extension. Biol. Rev. 0–000, https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12721 (2021).

Leggott, M. & Pritchard, G. Thermal preference and activity thresholds in populations of Argia vivida (Odonata: Coenagrionidae) from habitats with different thermal regimes. Hydrobiologia 140, 85–92 (1986).

Amano, T. Tapping into non-English-language science for the conservation of global biodiversity, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001296 (2021).

Amano, T. et al. The role of non-English-language science in informing national biodiversity assessments. Nat. Sustain. 6, 845–854 (2023).

White, C. R. et al. Geographical bias in physiological data limits predictions of global change impacts. Funct. Ecol. 35, 1572–1578 (2021).

Konno, K. et al. Ignoring non-English-language studies may bias ecological meta-analyses. Ecol. Evol. 10, 6373–6384 (2020).

Amano, T., González-Varo, J. P. & Sutherland, W. J. Languages Are Still a Major Barrier to Global Science. PLOS Biol. 14, e2000933 (2016).

Nuñez, M. A. & Amano, T. Monolingual searches can limit and bias results in global literature reviews. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 264–264 (2021).

Chowdhury, S. et al. Growth of non-English-language literature on biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Biol. 36, e13883 (2022).

Sundermann, A., Müller, A. & Halle, M. A new index of a water temperature equivalent for summer respiration conditions of benthic invertebrates in rivers as a bio-indicator of global climate change. Limnologica 95 (2022).

Hasnain, S. S., Shuter, B. J. & Minns, C. K. Phylogeny influences the relationships linking key ecological thermal metrics for North American freshwater fish species. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 70, 964–972 (2013).

Welch, J. & Jager, H. Thermal Tolerance Metrics for Freshwater Fish, CONUS, Version 1. Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), Oak Ridge, TN (United States) https://doi.org/10.21951/GMLC_THERMAL_METRIC/1897392 (2022).

Bonacina, L., Fasano, F., Mezzanotte, V. & Fornaroli, R. Effects of water temperature on freshwater macroinvertebrates: a systematic review. Biol. Rev. 98, 191–221 (2023).

Dahlke, F. T., Wohlrab, S., Butzin, M. & Pörtner, H.-O. Thermal bottlenecks in the life cycle define climate vulnerability of fish. Science 369, 65–70 (2020).

Pottier, P. et al. Developmental plasticity in thermal tolerance: Ontogenetic variation, persistence, and future directions. Ecol. Lett. 25, 2245–2268 (2022).

Sasaki, M. et al. Greater evolutionary divergence of thermal limits within marine than terrestrial species. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 1175–1180 (2022).

Comte, L. & Olden, J. D. Climatic vulnerability of the world’s freshwater and marine fishes. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 718–722 (2017).

Gunderson, A. R. & Stillman, J. H. Plasticity in thermal tolerance has limited potential to buffer ectotherms from global warming. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 282, 20150401 (2015).

Pinsky, M. L., Eikeset, A. M., McCauley, D. J., Payne, J. L. & Sunday, J. M. Greater vulnerability to warming of marine versus terrestrial ectotherms. Nature 569, 108–111 (2019).

Barbarossa, V. et al. Threats of global warming to the world’s freshwater fishes. Nat. Commun. 12, 1701 (2021).

Rohr, J. R. et al. The complex drivers of thermal acclimation and breadth in ectotherms. Ecol. Lett. 21, 1425–1439 (2018).

Sasaki, M. & Dam, H. G. Global patterns in copepod thermal tolerance. J Plankton Res 43, 598–609 (2021).

Bates, A. E. et al. Geographical range, heat tolerance and invasion success in aquatic species. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 280, 20131958 (2013).

Chown, S. L., Duffy, G. A. & Sørensen, J. G. Upper thermal tolerance in aquatic insects. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 11, 78–83 (2015).

Rohatgi: Webplotdigitizer: Version 4.5 - Google Scholar. https://apps.automeris.io/wpd4/.

Grosberg, R. K., Vermeij, G. J. & Wainwright, P. C. Biodiversity in water and on land. Curr. Biol. 22, R900–R903 (2012).

Mora, C., Tittensor, D. P., Adl, S., Simpson, A. G. B. & Worm, B. How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean? PLOS Biol. 9, e1001127 (2011).

Balian, E. V., Segers, H., Lévèque, C. & Martens, K. The Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment: an overview of the results. Hydrobiologia 595, 627–637 (2008).

Gillmann, S. M., Hering, D. & Lorenz, A. W. Habitat development and species arrival drive succession of the benthic invertebrate community in restored urban streams. Environ. Sci. Eur. 35, 49 (2023).

Nguyen, H. H. et al. Stream macroinvertebrate communities in restored and impacted catchments respond differently to climate, land-use, and runoff over a decade. Sci. Total Environ. 929, 172659 (2024).

Kunz, S. et al. Similarity of stream insect trait profiles across biogeographic regions. Divers. Distrib. 30, e13812 (2024).

Thorne, R. & Williams, P. The response of benthic macroinvertebrates to pollution in developing countries: a multimetric system of bioassessment. Freshw. Biol. 37, 671–686 (1997).

Harzing, A. W. Publish or Perish (2007).

Beck, H. E. et al. High-resolution (1 km) Köppen-Geiger maps for 1901–2099 based on constrained CMIP6 projections. Sci. Data 10, 724 (2023).

OpenTreeofLife et al. Open Tree of Life Taxonomy (2019).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2022).

Westgate, M. J. revtools: An R package to support article screening for evidence synthesis. Res. Synth. Methods 10, 606–614 (2019).

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019).

Barrett, T. et al. data.table: Extension of ‘data.frame’ (2024).

Michonneau, F., Brown, J. W. & Winter, D. J. rotl: an R package to interact with the Open Tree of Life data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 1476–1481 (2016).

Chamberlain, S. et al. taxize: Taxonomic Information from Around the Web (2022).

Pebesma, E. et al. sf: Simple Features for R (2024).

Hollister, J. et al. elevatr: Access Elevation Data from Various APIs (2023).

Hijmans, R. J., Barbosa, M., Ghosh, A. & Mandel, A. geodata: Download Geographic Data (2024).

Hijmans, R. J., Bivand, R., Dyba, K., Pebesma, E. & Sumner, M. D. terra: Spatial Data Analysis (2024).

Hester, J. et al. fs: Cross-Platform File System Operations Based on ‘libuv’ (2024).

Massicotte, P., South, A. & Hufkens, K. rnaturalearth: World Map Data from Natural Earth (2023).

Garnier, S. et al. viridis: Colorblind-Friendly Color Maps for R (2024).

Pedersen, T. L. patchwork: The Composer of Plots (2024).

Wilke, C. O. ggridges: Ridgeline Plots in ‘ggplot2’ (2024).

Bayat, H. S. hsbayat/Freshwater_thermtol_db: Freshwater thermal tolerance. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14056760 (2024).

Verberk, W. C. E. P., Hoefnagel, K. N., Peralta-Maraver, I., Floury, M. & Rezende, E. L. Long-term forecast of thermal mortality with climate warming in riverine amphipods. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 5033–5043 (2023).

Coutant, C. C. & Pfuderer, H. A. Thermal Effects. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 45, 1331–1369 (1973).

Bornmann, L., Haunschild, R. & Mutz, R. Growth rates of modern science: a latent piecewise growth curve approach to model publication numbers from established and new literature databases. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8, 1–15 (2021).

Keck, F., Broadbent, H. & Altermatt, F. Extracting massive ecological data on state and interactions of species using large language models. 2025.01.24.634685 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.01.24.634685 (2025).

Chen, X. & Zhang, X. Large language models streamline automated systematic review: A preliminary study. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.15702 (2025).

Tóth, B., Berek, L., Gulácsi, L., Péntek, M. & Zrubka, Z. Automation of systematic reviews of biomedical literature: a scoping review of studies indexed in. PubMed. Syst. Rev. 13, 174 (2024).

Cao, C. et al. Automation of Systematic Reviews with Large Language Models. 2025.06.13.25329541 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.06.13.25329541 (2025).

Wu, N. C. et al. Reporting guidelines for terrestrial respirometry: Building openness, transparency of metabolic rate and evaporative water loss data. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 296, 111688 (2024).

Waldvogel, A.-M., Schreiber, D., Pfenninger, M. & Feldmeyer, B. Climate Change Genomics Calls for Standardized Data Reporting. Front. Ecol. Evol. 8 (2020).

Vetter, D., Storch, I. & Bissonette, J. A. Advancing landscape ecology as a science: the need for consistent reporting guidelines. Landsc. Ecol. 31, 469–479 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank all student helpers who assisted in data extraction. We also thank the entire Collaborative Research Center RESIST for providing the research environment wherein this project developed. We appreciate all authors who authored the original work included, without whom this project could not be completed. Funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – SFB 1439/1 2021 – 426547801. AM acknowledges funding from the DFG – 326210499/GRK2360. FH acknowledges the support from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (E355S122). We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The database was conceptualized by R.B.S. and H.S.B., with input by F.H. to make it multi-lingual. H.S.B. developed the search protocol, harmonized existing databases, conducted literature searches in English and German, processed the final dataset, and wrote the manuscript. Data querying from English papers was conducted by H.S.B., S.P., K.P., J.F.J., J.W.S., A.M. and N.J.K. F.H. conducted the literature search in Chinese, and extracted the data along with X.C. Literature search and extraction for Spanish papers was conducted by G.M.M. and C.E.S. S.P. conducted pilot searches in Italian and Norwegian, and the search and data extraction in French. H.S.B., K.P. and F.H. conducted cross-checks of the data extracted by other collaborators. J.F.J. queried climate information. R.B.S. supervised the project and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bayat, H.S., He, F., Medina Madariaga, G. et al. Global thermal tolerance compilation for freshwater invertebrates and fish. Sci Data 12, 1488 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05832-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05832-w

This article is cited by

-

AmphiTherm: a comprehensive database of amphibian thermal tolerance and preference

Scientific Data (2025)