Abstract

The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) is a critical region in the Pearl River Delta along the South China coast and has a remarkably diverse seed plant species. However, factors such as rapid urbanization and climate change are increasingly impacting the resilience of the Greater Bay Area’s ecosystems. While morphology identification has many drawbacks such as slow process, incorrect identifications, and unreliable for distinguishing species at the growth stage; DNA barcoding has become a valuable tool in plant taxonomy by effectively overcoming many limitations of traditional methods. In this study, we constructed a comprehensive DNA barcoding database for native seed plants in the GBA using three barcodes (matK, rbcL, and ITS2). A total of 2864 native species from 1117 genera and 192 families were represented, of which 695 individuals from 516 species that were newly generated. This study enhances sustainable management and accurate identification of species, facilitates research on plant evolution and ecology, and supporting biodiversity monitoring and conservation efforts within the Greater Bay Area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (hereafter referred to as the GBA) comprises nine cities in Guangdong Province with the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macao. The GBA features a diverse geographical landscape, characterized by mountainous and hilly terrains to the east, west, and north, and predominantly covered by subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests and monsoon forests1. This region is distinguished by its humid subtropical climate and high summer precipitation, which foster a wide variety of flora and ecological interactions. The GBA is important for both its economic and innovative activity, as well as its diverse ecological support for various habitats. Seed plants, including angiosperms (flowering plants) and gymnosperms (conifers and their relatives), constitute the largest component of the region’s plant diversity. Despite its a rich botanical diversity, The GBA faces challenges related to plant conservation and sustainable land use. In recent decades, the degradation of vegetation within the GBA has primarily resulted from rapid urbanization, economic growth, and climate change2. As the area has evolved into a major economic hub in China, primary forests have increasingly been converted for infrastructure projects, resulting in substantial ecological degradation and biodiversity loss. This decline adversely affects essential ecosystem services, which are crucial for maintaining environmental balance in the region, necessitating extensive conservation efforts.

The species identification is crucial for the monitoring, conservation, and sustainable utilization of biodiversity. Traditional morphological classification methods typically rely on structural differences of plant organs. However, identifying species based on morphological characters can be challenging when dealing with specimens at early growth stage or those displaying similar characteristics due to shared environmental conditions, particularly among closely related or morphologically similar species3. The rapid advancement of DNA barcoding techniques has significantly improved the accuracy of species identification, even for specimens that have been processed or preserved for extended periods4,5,6,7. By addressing many limitations associated with traditional morphological taxonomy, DNA barcoding plays an essential role in biology research8,9. This approach utilizes one or a few standardized DNA sequences. While cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) has been recommend as universal marker for most animal species, it is not suitable for plants due to the slower evolutionary rate of mitochondrial genes in plants compared to those in animals8,10,11. Instead, two core plastid DNA barcode regions, namely partial sequences from the rbcL and matK genes, are employed as standard markers12. These regions are often supplemented with the more variable internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) region of nuclear ribosomal DNA to enhance resolution for seed plants13,14,15,16.

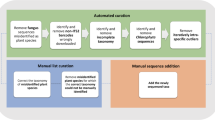

Establishing high-resolution and well-curated taxonomic reference libraries is a necessary first step to ensure accuracy in species identification and discovery17,18. A local DNA barcode library often proves more effective than a global DNA library due to its higher specificity and enhanced resolution. In this study, we constructed a reliable DNA barcode reference database for seed plants in the GBA using three standard barcodes matK, rbcL, and ITS2 (Fig. 1). The database comprises 2,864 native species across 1,117 genera and 192 families (Table 1). Among these, 695 samples representing 516 species were newly sequenced, contributing 1,860 sequences to GenBank and enriching the ITS2 barcode dataset. Additionally, there are 1,528 individuals with all three markers, which represent 1,002 species across 545 genera and 151 families.

The successful establishment of this comprehensive DNA barcode reference database marks a significant advancement in the understanding and preservation of plant diversity19. While previous libraries often centered on specific forest types or ecological zones20,21, our study provides a regionally targeted and taxonomically inclusive barcode reference library specifically for the GBA, which is distinctive in both its taxonomic breadth and its focus on a highly urbanized and fragmented landscape. Importantly, our dataset was constructed the critical gap in localized barcode representation.

The database aids in biodiversity monitoring and conservation initiatives by facilitating the rapid and accurate identification of species, including rare and endangered plants in the region. This resource not only enhances our understanding of plant biodiversity and supports effective conservation strategies globally but also bolsters future conservation efforts.

Methods

Generation of the seed plants list in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area

The seed plants list was derived from specimen records housed at the Herbarium of South China Botanical Garden (IBSC). Species names and taxonomic authorities were verified using the ‘status’ function of the R package ‘plantlist’ version 0.8.022 and cross-referenced with Plant of the world online (http://powo.science.kew.org/). The family classification follows APG IV for angiosperms23 and Yang et al.24 for gymnosperms. GBA has a total of 3,876 native seed species belonging to 1,229 genera and 198 families. Among them, 2,864 species from 1,117 genera and 192 families were included in this study (Table 1). Details could be found in the Table S1 at Figshare25, since leaves materials and sequence data could not be obtained for the remaining species. Available barcodes information for included species is documented in “Barcodes information” at Figshare25.

Sample collection and data acquisition

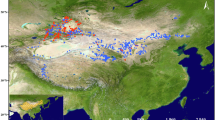

From September 2022 to December 2024, field expeditions were conducted to collect specimens across eight cities in Guangdong Province: Zhaoqing, Foshan, Jiangmen, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Huizhou, Shenzhen, and Zhuhai (Fig. 2, “Barcode Dataset” at Figshare25). Fresh leaves were preserved in silica gel during the fieldwork, and voucher specimens were deposited in the herbarium of the South China Botanical Garden (IBSC).

In addition, we incorporated partial standard barcode data from a previous study on subtropical regions in southern China20,26. To enhance the representation of taxa and genetic variation among seed plants species in the GBA, we retrieved a set of barcode sequences from GenBank. Sequences were manually filtered to exclude those that were low-quality (e.g., truncated, ambiguous, lacking voucher data) or taxonomically inconsistent (e.g., outdated synonyms, misspellings, or provisional names not present in the checklist).

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from silica-dried leaves following the cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method27, which involves several steps, including cell lysis, removal of protein and debris, and DNA recovery. Sequencing was performed using universal DNA barcode primers for rbcL28 (rbcLa_F: ATGTCACCACAAACAGAGACTAAAGC; rbcLa_R: GTAAAATCAAGTCCACCTCG), matK (K. J. Kim, unpublished, matK_3F: CGTACAGTACTTTTGTGTTTACGAG, matK_1R: ACCCAGTCCATCTGGAAATCTTGGTTC), and ITS2 region was amplified using the primers ITS2_S2F/ITS2_S3R15 (ITS2_S2F: ATGCGATACTTGGTGTGAAT; ITS2_S3R: GACGCTTCTCCAGACTACAAT). The PCR reaction mixture consisted of 25 μl. which included 2.5 μl of 10 × PCR buffer (Tris-HCl, 100 mM; KCl, 500 mM; MgCl2, 15 mM), 0.5 μl of each primer (10 μM), 2.0 μl of dNTPs (2.5 µM), 0.5 μl of DNA template (about 20~30 ng), 0.2 μl of rTaq (5 U µl−1), and 18.8 μl of ddH2O29. The PCR amplification was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for three minutes; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 50 °C for rbcL, 48 °C for matK, and 55 °C for ITS2 for 45 seconds, followed by extension at 72 °C for one minute, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 minutes. All PCR products were visualized on a 1.0% agarose gel and sequenced using Sanger sequencing on an ABI3730 DNA analyzer. Both PCR product purification and Sanger sequencing were carried out by Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Raw sequences were subsequently edited and assembled using Geneious 11.0.230,31.

All the sequences obtained by Sanger sequencing were verified using the BLASTn tool. In instances where certain species were absent from the GenBank database, the target fragments with the highest bit-scores from sequence accessions of the same genus or family were considered reliable. A total of 695 samples included at least one verified sequence in this study.

Data verification

To minimize the impact of missing data, analyses were restricted to species represented by multiple individuals. Raw sequences were aligned using MAFFT v7.4714532 and manually refined in Geneious 11.0.230. Default parameters were applied for aligning rbcL and matK sequences, while ITS2 sequences were aligned by the order level. Following alignment, barcode concatenation was performed to calculate the resolution percentages for various barcode combinations. Three widely recognized methods were employed to assess the efficacy of DNA barcodes in species authentication: (1) Barcoding gap Method: Species with multiple specimens were analysed to detect a barcode gap, characterized by the smallest interspecific genetic distance exceeding the largest intraspecific genetic distance33. The uncorrected intra- and interspecific genetic distances were calculated using the “distancematrix” function in R34. (2) Similarity-Based Method: The percentage of correctly identified sequences was determined using the “BM/BCM (best match/best close match)” function in “taxonDNA”. In ‘best match’ analysis, each query is to find out its closest barcode match, whereas the ‘best close match’ was more rigorous, as it depended on a 95% pairwise distance threshold35. Pairwise genetic distances were calculated using the Kimura 2-parameter (K2P) model. (3) Tree-Based Method: Monophyletic clades with bootstrap support of at least 50% were classified as successful identifications. A Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was constructed using a combination of three genetic markers based on the GTRGAMMA model in the “raxml-hpc2” (v8.2.12) on CIPRES platform, with 1,000 bootstrap replicates to estimate node support36.

Data Records

The collection of 695 individuals representing 516 species were successfully sequencing, yielding 591 matK, 680 rbcL, and 589 ITS2 sequences. All DNA barcodes are accessible in GenBank, with the following accession numbers: PQ331846-PQ332525 for rbcL, PQ331250-PQ331840 for matK, and PQ564758-PQ565346 for ITS2. The sequence record lists could be found in three supplementary files at Figshare (Tables S2–S4)25. Detailed information on the newly generated sequences is provided (Table S2). For species reported in this region but lacking sufficient quality samples for DNA barcode sequencing, we selected 5,661 standard barcodes from 887 species based on our previous studies conducted in subtropical regions of China (Table S3)20,26. Additionally, we incorporated 12,838 sequences downloaded from GenBank (Table S4), encompassing 1461 species across 832 genera and 165 families.

In total, this database comprises 20,359 standard barcodes, covering 2,864 native species from 1,117 genera within 192 families in the GBA37. The families with the highest species diversity include Poaceae, with 219 species of 97 genera; Fabaceae, with 171 species from 74 genera; and Orchidaceae, with 134 species representing 54 genera (Table 2). All specimen details and standard DNA barcode sequences have been uploaded to the BOLD system, which is publicly available, under the name of dataset “DS-GHMGBA”37 (https://doi.org/10.5883/DS-GHMGBA). All supplementary files for this study are shared at Figshare25.

Technical Validation

We evaluated the discriminatory power of the standard barcodes among species with multiple individuals using three common methods (Table 3, Fig. 3). The ITS2 marker exhibited the highest species resolution compared to other single barcode fragments, achieving identification rates of 87.6%, 69.7 2%, and 70.87% for BM/BCM method, the barcoding gap, and the tree-based method, respectively. However, we found that among some higher-level taxonomic groups (such as above the family or order level), the ITS2 sequences are so highly variable that it becomes very difficult to align the sequences effectively. In addition, ITS2 is also prone to fungal contamination and contains a large number of paralogous copies38. All of these factors hinder the accuracy of using ITS2 alone as a DNA barcode region.

The species level discrimination rate for three barcodes and their combinations using three different methods. BM/BCM: Best Match/Best Close Match; RM: rbcL + matK; RI2: rbcL + ITS2; MI2: matK + ITS2; RMI2: rbcL + matK + ITS2. The results for BM and BCM were identical across all barcodes in this study; only a single set of values is presented.

In contrast, rbcL and matK provided lower resolution, with identification rate of 56.2% for rbcL and 63.29% for matK using the BM/BCM method. These results are significantly lower than the 90% successful identification rate reported by Lahaye et al.39 for 1,084 angiosperm species. Using the barcoding gap method, the identification rates of matK and rbcL were 46.9% and 35.72%, respectively, while the tree-based method yielded rates of 31.89% for rbcL and 43.5% for matK. The combination of all two plastid barcodes (matK and rbcL) yielded results that fluctuated around 55%. Similar findings have been reported in recent studies focusing on seed plants40,41,42,43. The combination of rbcL + matK + ITS2 (referred to as RMI2) had the highest species resolution for both the barcoding gap and the tree-based method (Table 3), with rates of 76.83% and 71.63%, respectively. Therefore, combining nuclear (ITS2) and plastid markers (rbcL and matK) remains the most robust strategy, balancing primer universality, species resolution, and broader taxonomic applicability13.

The maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was constructed using RMI2, based on 1,399 samples representing 979 species from 505 genera across 148 families and 47 orders (Fig. 4). Of the nodes in the tree, 17.83% exhibited support rates below 50%, while 14.35% displayed moderate support, with values ranging from 50% to 75%. Notably, 67.82% of the nodes had support values exceeding 75%, providing adequate resolution to distinguish most genera and families. However, we found 42 of the 505 genera appeared as non-monophyletic in the tree. In these cases, we cannot completely rule out the possibility of systematic errors (limited phylogenetic signals of barcodes); however, some instances may also be attributed to the inherent complexity of plant group classification. For example, Turpinia and its relatives are readily distinguishable morphologically, but molecular evidence fails to effectively differentiate them44, as demonstrated in this study. There are also some genera, such as Castanopsis, Lithocarpus, and Quercus (Fagaceae), that could not be effectively distinguished by the current DNA barcodes. This is likely due to strong hybridization and introgression events that have occurred among these genera in the past45. The same thing might have happened in Lauraceae as well46. Overall, the creation of a DNA barcode database for the GBA region offers substantial benefits for plant species identification, efficient biodiversity monitoring, and research on plant evolution within the region. We will continue to improve and expand this database to better meet the needs of the local community.

Code availability

The code used to check species authorities is available in the R package ‘plantlist’ version 0.8.0.

References

Ren, H., Lu, H., Wang, J., Liu, N. & Guo, Q. Forest restoration in China: advances, obstacles, and perspectives. Tree For. Sci. Biotech. 6, 7–16 (2012).

Yang, C. et al. Rapid urbanization induced extensive forest loss to urban land in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 31, 93–108 (2021).

Mishra, P. et al. DNA barcoding: an efficient tool to overcome authentication challenges in the herbal market. Plant Biotech. J. 14, 8–21 (2016).

Dasmahapatra, K. K. & Mallet, J. Taxonomy: DNA barcodes: recent successes and future prospects. Heredity 97, 254–255 (2006).

Hubert, N. & Hanner, R. DNA Barcoding, species delineation and taxonomy: a historical perspective. DNA Barcodes 3, 44–58 (2015).

Zhu, S., Liu, Q., Qiu, S., Dai, J. & Gao, X. DNA barcoding: an efficient technology to authenticate plant species of traditional Chinese medicine and recent advances. Chin. Med. 17, 112 (2022).

Hebert, P. D. N., Cywinska, A., Ball, S. L. & deWaard, J. R. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 270, 313–321 (2003).

Kress, W. J., Wurdack, K. J., Zimmer, E. A., Weigt, L. A. & Janzen, D. H. Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102, 8369–8374 (2005).

Kress, W. J. & Erickson, D. L. A two-locus global DNA barcode for land plants: The coding rbcL gene complements the noncoding trnH–psbA spacer region. PLoS One 2, e508 (2007).

Burgess, K. et al. Discriminating plant species in a local temperate flora using the rbcL plus matK DNA barcode. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2, 333–340 (2011).

de Boer, H. J., Ouarghidi, A., Martin, G., Abbad, A. & Kool, A. DNA barcoding reveals limited accuracy of identifications based on folk taxonomy. PLoS One 9, e84291 (2014).

CBOL Plant Working Group. et al. A DNA barcode for land plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106, 12794–12797 (2009).

China Plant BOL Group. et al. Comparative analysis of a large dataset indicates that internal transcribed spacer (ITS) should be incorporated into the core barcode for seed plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 19641–19646 (2011).

Yao, H. et al. Use of ITS2 region as the universal DNA barcode for plants and animals. PLoS One 5, e13102 (2010).

Chen, S. et al. Validation of the ITS2 region as a novel DNA barcode for identifying medicinal plant species. PLoS One 5, e8613 (2010).

Schoch, C. L. et al. From the cover: nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109, 6241–6246 (2012).

Jones, L. et al. Barcode UK: A complete DNA barcoding resource for the flowering plants and conifers of the United Kingdom. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 2050–2062 (2021).

deWaard, J. R., Hebert, P. D. & Humble, L. M. A comprehensive DNA barcode library for the looper moths (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) of British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One 6, e18290 (2011).

Costion, C. et al. Building a plant DNA barcode reference library for a diverse tropical flora: an example from Queensland, Australia. Diversity 8, 5 (2016).

Jin, L. et al. A DNA barcode library for woody plants in tropical and subtropical China. Sci Data 10, 819 (2023).

Song, F. et al. Plant DNA barcode library for native flowering plants in the arid region of northwestern China. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 23, 1389–1402 (2023).

Zhang, J. Plantlist: Looking Up the Status of Plant Scientific Names based on The Plant List Database. R package version (0.8.0), https://github.com/helixcn/plantlist (2022).

Zuntini, A. R. et al. Phylogenomics and the rise of the angiosperms. Nature 629, 843–850 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Recent advances on phylogenomics of gymnosperms and a new classification. Plant Divers. 44, 340–350 (2022).

Le, T. M. T. et al. A DNA barcode reference of seed plants in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27909693 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. The use of DNA barcoding as a tool for the conservation biogeography of subtropical forests in China. Divers. Distrib. 21, 188–199 (2015).

Doyle, J. J. & Doyle, J. L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19, 11–15 (1987).

Kress, W. J. et al. Plant DNA barcodes and a community phylogeny of a tropical forest dynamics plot in Panama. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106, 18621–18626 (2009).

Filichkin, S. A. & Gelvin, S. B. Effect of dimethyl sulfoxide concentration on specificity of primer matching in PCR. Biotechniques 12, 828–830 (1992).

Kearse, M. et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649 (2012).

Ripma, L. A., Simpson, M. G. & Kristen, H. L. Geneious! Simplified genome skimming methods for phylogenetic systematic studies: A case study in Oreocarya (Boraginaceae). Appl. Plant Sci. 2, 1400062 (2014).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Gill, B. A. et al. Plant DNA-barcode library and community phylogeny for a semi-arid East African savanna. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 19, 838–846 (2019).

Wright, E. S. Using Decipher v2.0 to analyze big biological sequence data in R. R J 8, 352–359 (2016).

Meier, R., Shiyang, K., Vaidya, G. & Ng, P. K. DNA barcoding and taxonomy in Diptera: a tale of high intraspecific variability and low identification success. Syst. Biol. 55, 715–728 (2006).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Le, T. M. T. et al. Dataset: DS-GHMGBA. https://doi.org/10.5883/DS-GHMGBA (2024).

Feliner, G. N. & Rosselló, J. A. Better the devil you know? Guidelines for insightful utilization of nrDNA ITS in species-level evolutionary studies in plants. Mol. Phyl. Evol. 44, 911–919 (2007).

Lahaye, R. et al. DNA barcoding the floras of biodiversity hotspots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 105, 2923–2928 (2008).

Gong, L. et al. Constructing a DNA barcode reference library for southern herbs in China: A resource for authentication of southern Chinese medicine. PLoS One 13, e0201240 (2018).

Hu, J. L. et al. Assessing candidate DNA barcodes for Chinese and internationally traded timber species. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 22, 1478–1492 (2022).

Wirta, H. et al. Establishing a community-wide DNA barcode library as a new tool for arctic research. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 16, 809–822 (2016).

Mao, X. et al. Establishing community-wide DNA barcode references for conserving mangrove forests in China. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 571 (2021).

Harris, A. J. et al. A molecular phylogeny of Staphyleaceae: Implications for generic delimitation and classical biogeographic disjunctions in the family. J. Syst. Evol. 55(2), 124–141 (2017).

Zhou, B. F. et al. Phylogenomic analyses highlight innovation and introgression in the continental radiations of Fagaceae across the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Commun. 13, 1320 (2022).

Liu, Z. F. et al. DNA barcoding evaluation and implications for phylogenetic relationships in Lauraceae from China. PLoS One 12, e0175788 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Science & Technology Fundamental Resources Investigation Program (Grant No. 2022FY100500) and the Guangdong Flagship Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (Grant No. 2023B0303050001). We thank Lu-Lu Zhang and Yu-Ying Zhou for their contributions to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.J.G. and H.F.Y. conceived and designed the study; X.J.G., R.J.W. and Y.F.D. collected the voucher specimens and fresh leaf materials; T.M.T.L. performed the laboratory works; T.M.T.L., L.J. and X.K. L. analysed data, and T.M.T.L. wrote the manuscript. X.J.G. and H.F.Y. revised and finalized the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Le, T.T.M., Jin, L., Wang, RJ. et al. A DNA barcode reference library of native seed plants in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Sci Data 12, 1505 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05833-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05833-9