Abstract

Faults have the potential to generate earthquakes causing significant damage to societal infrastructure and life losses. Innovative methodologies and multidisciplinary research approaches are essential for assessing seismic hazard in areas where the study and parametrization of earthquake-generating faults present significant challenges, for example due to the scarcity of fault exposures. This is the case of the Northern Apennines front (Italy), where active and seismogenic faults are concealed beneath thick sedimentary deposits. To study the local seismotectonic framework we present a new 3D model for a sector of the Northern Apennines Pedeapenninic margin between Parma and Bologna. The model was generated by integrating geological, geophysical and seismological datasets in the software Leapfrog Works. It assembles eight primary geological units from the surface down to ∼15 km depth and allowed for the reconstruction of 54 active faults, including 12 seismogenic faults. The main aim of this study is to introduce a 3D seismotectonic database that serves scientific, educational and practical applications and can be used for seismic hazard analytical assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Among natural phenomena posing a potential risk to society and infrastructure, fault-related seismicity and surface faulting in tectonically active regions are particularly significant and represent a major concern. Italy is one of the most exposed countries to this kind of geological risk and has long devoted considerable scientific attention to the topic. A significant input to modern research in the field of seismotectonics in Italy dates to the aftermath of the 1980 Irpinia earthquake1,2,3, a catastrophic event that caused extensive damage to infrastructure and the regional economy, as well as more than 2,700 fatalities1. Research has since progressively led to the understanding that strong earthquakes can recur over time along the same triggering structure (i.e., the seismogenic fault) and to the appreciation of the importance of the causal and spatiotemporal connection between the parametrization of the earthquake-generating sources and the coseismic deformation at the surface4,5,6. After that earthquake, a series of national research programs —particularly those developed within the GNDT (Gruppo Nazionale per la Difesa dai Terremoti) framework— have played a crucial role in shifting the scientific approach from the use of areal seismogenic zones to the identification and parametrization of individual seismogenic faults, thus laying the foundations for modern, fault-based seismic hazard models (https://emidius.mi.ingv.it/GNDT2/). Recently, structural maps displaying active and seismogenic fault traces in seismically active areas have also become a further key tool in seismotectonic studies, and numerous techniques for analyzing both fossil and recent seismotectonic data have been developed7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Following the numerous and destructive earthquakes that have affected the Italian territory over the last decades (e.g., L’Aquila in April 2009; Emilia-Romagna in May 2012, and Central Italy in 2016), studies related to seismic hazard and active and/or seismogenic faults (see the scientific definition in the following section) are still on the rise15,16,17,18,19. To aid governmental decisions as well as planning and regulation of the territory in seismically active regions, national guidelines have been produced both in Italy20 and abroad. These guidelines, however, generally describe procedures and study protocols that are mostly suitable for well exposed areas, with abundance of surface faulting (i.e., “capable” faults) and coseismic structures.

In the absence of surface exposures of these structures, though, field-based deterministic studies are extremely difficult, if not impossible (indeed, a situation not uncommon in areas affected by neotectonic activity). This is often the case in active mountain chain fronts, where the low relief of the orogenic front and the geological characteristics and essentially flat morphology of the foreland tend to conceal the most external, seismically active faults of the chain beneath thick sedimentary deposits.

Consequently, a different methodological approach is required to fill the knowledge gaps due to poor outcrop conditions. With this study we provide one of the few existing 3D seismotectonic databases for an active mountain chain front, compiling seismological, geophysical and geological datasets to specifically address the following two critical issues: i) How can we positively identify active and/or seismogenic faults in areas at the front of an active mountain chain where significant fault structures capable of generating substantial displacements and seismicity are buried under several kilometers of mostly undeformed sediments? ii) How can we reconstruct the real 3D fault geometries to be used as a key geometric input to fault parametrization, which, in turn, is required for seismic hazard assessments?

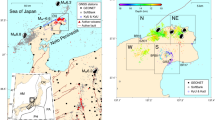

As an example, we use the Northern Apennines of Italy, where the blind thrusts responsible for the 2012 seismic sequence in the Po Plain in response to the NE-SW shortening of the belt are still deeply buried and, thus, not directly accessible (Fig. 1). We have created a 3D seismotectonic model encompassing a sector of the Northern Apennines Pedeapenninic margin (PAM) between the cities of Parma and Bologna, extending from the inner mountain chain to the external foreland of the fold-and-thrust belt.

(a) Schematic structural framework of the study area19. (b) Geological-structural map of the Northern Apennines (modified after ref. 44). The dashed layout highlights the study area. Main active faults are taken from the Italian national database29. Focal mechanisms are derived from the RCMT catalogue (INGV - RCMT)68. PAM: Pedeapenninic margin. (c) Geological cross-section showing the overall structuring of the Northern Apennines belt, redrawn from ref. 48.

To date, there only exist a few 3D seismotectonic models at a regional scale like the one we propose here21,22. New Zealand and Japan, for example, have 3D databases of active and seismogenic faults23,24 and in Europe there is a database of 3D models from different countries (Home - EGDI). In Italy, also thanks to the national geological mapping project (CARG project), some geological models have already been produced25,26,27,28. In 2024, the Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA) launched and published its own freely accessible 3D viewer, which can be freely consulted (https://geo-it3d.isprambiente.it/map).

Through our 3D Northern Apennines model and database, we share the results of a scientific approach that also aims at representing a starting point for more studies on seismic hazard based on robust deterministic geological inputs (see Usage Notes section). Additionally, we wish for it to be also used for other scientific purposes, as well as for educational and outreach efforts.

Active, seismogenic and capable faults: adopted nomenclature

Our knowledge regarding the characterization of active and seismogenic faults has recently advanced significantly, also due the development of databases29,30,31 and national-scale seismic hazard maps32. This has required significant efforts by the scientific community, particularly towards the adoption of a unified nomenclature to precisely describe and characterize the identified structures. Examples are the terms “active” and “seismogenic” faults.

Here we adopt the definition of Active Faults (AFs) by ISPRA, which describes a fault as “active” if it has been activated at least once during the last 125,000 years, i.e., in the Late Pleistocene. This definition is applicable to faults located at plate boundaries33. In more detail, in the ITHACA national catalogue (ITaly HAzard from CApable faults29) ISPRA includes both active faults (last activity < 125,000 ka) and potentially active faults (last activity between 125 ka and 2.58 Ma).

A fault is considered “seismogenic” when its ruptures are capable of generating earthquakes within a time frame of social interest29. Additionally, a fault is considered “capable” if it is able to intersect the topographic surface. In some cases, we can observe and study directly in the field faults that are active, seismogenic and capable34, while in others, we can only observe a diffuse array of deformation features indicative of active faulting at the surface, which is then tentatively linked to the corresponding deep seismogenic source, a correlation that is not always straightforward.

Tectonic and geological setting

The Northern Apennines (NA) are an orogenic system originating in a convergence setting as a result of the collision between the Adria and Europe plate margins35,36,37,38,39,40,41.

The NA fold-and-thrust belt (Fig. 1c) formed through various tectonic phases, involving earlier NE-SW compression and subsequent NE-SW extension. Compression primarily led to the formation of the NA orogenic wedge, which is still structuring in the outermost sector of the belt. Extension, on the other hand, has been affecting the inner sectors of the NA since the Miocene, coinciding with the opening of the Tyrrhenian back-arc domain36,41,42,43.

Subduction and accretion have led to the stacking of different paleogeographic domains44,45,46,47. These include (i) the Ligurian and Subligurian Units, consisting of ophiolitic sequences and their sedimentary cover, overlain unconformably by (ii) the Epiligurian Units deposited within wedge-top basins; (iii) the Tuscan Units; and (iv) the Umbria-Marche-Romagna Units, which were originally part of the passive Adria margin. Additionally, we considered the (v) Miocene-Pleistocene foreland deposits found in the Po Plain and along the Northern Apennines Pedeapenninic margin.

The Tuscan and Subligurian units predominantly crop up in the inner and axial sector of the chain, to the south of the study area, where extensional tectonics have led to the formation of intermontane basins such as the Mugello, Garfagnana, and Lunigiana basins (e.g., ref. 48; Fig. 1b). Moving farther to the north, the Ligurian and Epiligurian units crop out, extending all the way to the PAM, i.e., the morphological boundary between the Apennines and the Po Plain, where the most recent Pliocene-Pleistocene units are exposed at the surface (Fig. 1).

The current configuration of the NA external front was largely shaped during Pliocene-Early Pleistocene times. It is defined by the WNW-ESE striking Emilia and Ferrara arcs (Fig. 1b), composed of thrusts and associated folds, which lie beneath the middle Pleistocene-Holocene deposits of the Po Plain foredeep49,50,51.

This geological architecture fits well the present-day seismicity in the NA. Earthquakes linked to thrusting are observed along the exposed front of the belt and are also clustered along the concealed thrusts beneath the Po Plain, particularly along the Emilia and Ferrara arcs and along the Pedeapenninic margin (PAM), a structure consisting of multiple NW-SE fault segments that mark the morphological boundary between the plain and the foothills12,13,19,48,50 (Fig. 1b). Conversely, seismic activity related to extensional tectonics is associated with the NW-SE trending normal faults that bound extensional basins within the inner sector of the belt12,13,40,48,50 (Fig. 1b).

Methods

The workflow we adopted for the creation of the 3D model is illustrated in Fig. 2; it consists of four main stages that are described here below:

Workflow, Stage I: input data collection

To generate a valid and usable 3D seismotectonic model, access to a comprehensive dataset is essential, as the accuracy and reliability of the end model are highly dependent on the quality and quantity of the available input information. This may include geological maps, cross-sections, deep borehole data, seismic profiles, seismological data, shear wave velocity profiles, and stress field data (see workflow in Fig. 2). All sources used for 3D modelling are open access and are published on free official national or regional platforms (see next chapters). A summary of the main 2D input data is reported in Table 1.

Geological input data

To create an appropriate methodological approach and workflow for our 3D model and to ensure its accurate geological and geodynamic context, it was necessary to compile as many geological constraints on the study area as possible. In detail, we studied the geological and morphological transition zone between the Northern Apennines chain and the outermost fold-and-thrust belt presently buried beneath the Po Plain foreland (PAM, Fig. 1), a region known for its high seismic activity, including the 2012 Emilia earthquake16,48.

Our 3D model encompasses the area between the cities of Parma and Bologna (Fig. 1b), where we19 recently carried out an in-depth field campaign along the PAM.

From a geological-structural perspective, we implemented the 3D geometries of active and seismogenic extensional faults in the inner sector of the chain and of buried thrusts. Additionally, strike-slip faults were incorporated in the chain sector of the study area when they could be constrained as displacing the thrusts of the PAM (Fig. 1b).

To obtain a manageable 3D model, the highly complex stratigraphy of the study area was simplified by grouping the numerous geological bodies into eight main, higher-order stratigraphic units, thus keeping consistence with the real geology but avoiding unnecessary complications due to excessively detailed subdivisions. The eight main stratigraphic units, identified also in agreement with the seismotectonic maps of the Emilia-Romagna region48,51, are reported in the logs of Fig. 3. In detail, we decided to group the Ligurian, Subligurian and Epiligurian units into a single block, called “Allochthonous Units”, and to subdivide the heterogeneous Tuscan and Umbria-Marche Romagna units into homogeneous sub-units according to their age and tectonic significance: the crystalline basement, the Triassic units, the Mesozoic-Cenozoic carbonate successions and the Oligocene-Miocene syn-orogenic deposits (Autochthonous Units). Finally, the Miocene-Present foreland deposits were subdivided into Pliocene, Early-Pleistocene and Middle Pleistocene-Holocene units (Fig. 3).

The input geological dataset for the construction of the model includes: i) digital elevation and/or digital terrain models (DEM, DTM), ii) geological maps, iii) cross-sections from the literature and derived from our own fieldwork along the PAM19, and iv) stratigraphic logs from boreholes drilled for oil and gas exploration. A DTM of the Emilia-Romagna Region with a resolution of 5 × 5 m in the EPSG:32632 WGS84/UTM zone 32 N cartographic reference system (available at https://geoportale.regione.emilia-romagna.it) was used as topographic base (Fig. 4a). The DTM was remotely sensed along the orographic watershed and along the Apennines-Po Plain transition zone, where some morphotectonic features occur and can potentially disclose information about primary structural elements (such as the presence of morphological alignments oriented in a specific direction, potentially alternated with depressed areas like valleys; or abrupt changes in the morphology of the mountain margin or of the course of rivers/streams, or the presence of clear linear elements of discontinuity, known as lineaments). The presence of hilly/mountainous ridges having the same orientation and of valleys oriented in the same direction could indicate the presence of folds shaping the landscape. Clear lineaments that cut across morphologies or border mountain margins and valleys could, instead, be attributed to faults.

(a) Polylines used to map stratigraphic boundaries and faults within each input dataset in Leapfrog Works; (b) Primary 3D attitude of stratigraphic surfaces interpolated from the polylines in a); (c) The model includes the 3D attitude of active and/or seismogenic faults mapped using input data and polylines.

Regarding the mountainous and hilly sector of the study area, geological maps at the 1:50,000 scale from the Italian CARG geological mapping project for the Emilia-Romagna Region (https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/Media/carg/emilia.html) were used as reference. Additionally, two regional seismotectonic maps48,51 containing information about active fault traces and seismogenic sources in the Emilia-Romagna were implemented in the model. All geological sections associated with the CARG project and seismotectonic maps within the area were also collected (Fig. 4b). The twenty-three existing geological cross-sections available for the study area collected from the CARG project are generally highly detailed but extend to a depth of only a few hundred meters below the surface, whereas the six cross-sections from the seismotectonic maps (Fig. 4b) only indicate the main stratigraphic boundaries in the area but reach depths of up to tens of kilometers below the surface, especially for the Po Plain area. The combination of these two input datasets provides a multi-scale view of the geology of the study area.

In the Apennines-Po Plain margin sector, a detailed geological survey was conducted to search for evidence of tectonic activity along some poorly exposed segments of the PAM, as reported by ref. 19. They reported eight detailed cross-sections that were incorporated into the 3D model. Active thrust segments identified thanks to ref. 19 were used to create the segments of the PAM in the 3D model. As for the geology of the Po Plain sector, in addition to the few available sections, a total of 113 stratigraphic boreholes were extracted from the Vi.De.Pi project website (https://www.videpi.com/videpi/videpi.asp), which is an archive of bore-holes and seismic lines conducted for mining and oil and gas exploration in Italy. A key step to conclude this part of the geological data collection was the standardization of these data to create a homogeneous dataset ready for import into the software. A criterion of dividing the succession was adopted, following a geometric approach consistent with regional seismotectonic maps. As a result, the high-detailed stratigraphy of the CARG geological cross-sections and of the deep boreholes was grouped into eight main units described above (Fig. 3).

In addition to these data, information on active and seismogenic faults in the area was collected from both the literature and two national reference databases29,30.

Geophysical and seismological input data collection

The geophysical input data for the creation of the 3D model belong to two categories: i) Deep seismic lines, ii) Horizontal stress indicators. The latter were sourced from the IPSI (Italian Present-day Stress Indicators52,53,54 and are mostly derived from borehole breakout data. Borehole breakouts are stress-induced enlargements of the wellbore cross-section that occur when drilling through rock in an anisotropic stress field55,56. These data were integrated with seismological information to analyze stress field variations across the region and to assess its compatibility with the activation and slip along the most recent (active) faults.

As to the deep seismic lines, we selected the most informative from the Vi.De.Pi database (https://www.videpi.com/videpi/videpi.asp). Only lines that had already been migrated from time to depth, interpreted, and deemed of good quality were included, resulting in a total of 18 selected lines.

To ensure accurate georeferencing in the 3D model, it was crucial to determine the exact surface trace positions of these seismic lines (Fig. 4b).

We used a database of 8,130 instrumental recordings of seismic events from 1985 to 202357. Additionally, 361 events were included from the historical CPTI15 catalogue58,59, and 79 focal mechanisms were incorporated from ref. 48.

Workflow-Stage II: Georeferencing the input data into the 3D modeling software

The 2D input data were fed to the Leapfrog Works 3D modeling software, licensed by Seequent, version 2023 (https://www.seequent.com/products-solutions/leapfrog-works/), through the following process:

-

I).

The input 2D shapefile format (.shp) data such as geological cross-sections, seismic lines, and traces of active faults as from the national databases, were reprojected in the QGIS software (https://www.qgis.org/it/site/) to the EPSG:32632 WGS84/UTM zone 32 N reference system and were then imported into Leapfrog Works. For the hypocenters of instrumental/ historical seismic events and focal mechanisms48,57,59, as well as for borehole breakout data, the associated attribute tables were also imported to enable plotting at their respective depths.

-

II).

Topography (DTM) and high-resolution maps were georeferenced using QGIS as.tif files and imported into Leapfrog Works.

Cross-sections and seismic lines were located based on their surface traces in QGIS and subsequently imported into Leapfrog Works. For each of these traces, vertical planes were inserted, and the sections were georeferenced on these planes. For each borehole, two.csv format tables were generated containing information about the location, depth, and geological units present, with their corresponding depth intervals. These tables were then imported into the software using the dedicated “Boreholes” function.

Workflow-Stage III: Interpretation and interpolation process

To create 3D geometries and thus construct the seismotectonic model, stratigraphic boundaries of the main eight geological units described above, and the faults were identified and mapped directly on the previously georeferenced objects using polylines (Fig. 4a). Polylines are objects provided by Leapfrog Works and serve as a fundamental constraint for the creation of 3D surfaces (meshes). Polylines have their own polarity (positive in red and negative in blue in Fig. 4a), and it is important to maintain such polarity consistent for polylines belonging to the same geometry. If this is not done, the resulting geometry will be incorrect. To create a mesh, it is necessary to define its domain within the modelled area (lateral and vertical extents) and ensure the mesh passes through one or more polylines representing deterministic constraints upon which these surfaces are based. For the construction of stratigraphic boundaries, these were mapped in each cross-section, seismic line, well, and map (as shown in Fig. 4a). As mentioned, we only mapped geological units that were clearly identifiable across most datasets due to the varied data sources, scales, and levels of detail. We intentionally simplified the stratigraphy, focusing on the most recent units (Pleistocene to Holocene) because they are most relevant for identifying active faults (Fig. 4a).

The same procedure was followed also for the generation of the modeled faults, which proved to be more complex of a task since the same tectonic structure had to be identified and traced across various data sources. We thus decided to only map active and/or seismogenic faults that were clearly recognizable on various sections due to their position, geometry, and the stratigraphic horizons they displace, all supported by bibliographic data. In particular, we modelled only the main thrust, normal or strike-slip faults when their geometry, both at depth and along strike, could be clearly identified in at least two adjacent cross-sections or seismic lines, omitting lower-order structures. Once stratigraphic boundaries (Fig. 4b) and active faults (Fig. 4c) were mapped through polylines, the corresponding 3D planes were created using a dedicated function. The Leapfrog Works suite employs an interpolation technique, using a specialized tool called FastRBF™ developed by ARANZ Geo. This tool significantly accelerates the process enabling dynamic model updates (https://www.seequent.com/leapfrog-interpolation-basics/).

Interpolation was used to estimate a value at a specific position in space, denoted as X, when it is only known at other locations, typically from drillhole data or cross-sections. Under the guidance of the user’s expertise, Leapfrog utilizes the algorithm FastRBF™ to interpolate missing data, filling gaps where information is lacking. Thanks to the speed of FastRBF™, the model updates dynamically as new data are incorporated. Leapfrog Works employs two primaries’ interpolants: a linear interpolant and a spheroidal interpolant. For the 3D geometry reconstructed in this work we used the linear interpolant, which assigns weights based on the distances between known points and a given location. The mesh resolution was set to be adaptive, thus varying according to the quality and quantity of data available for a given fault.

Workflow-Stage IV: Creation of the final 3D seismotectonic model

To complete the process and generate the final seismotectonic model, the “Geological Model” function in Leapfrog Works version 2023 was used. This function enables the assembly of the previously created 3D geometries into a unifying geological model (Fig. 5a,b). To accomplish this, the model’s extent was first defined, naturally aligning with the topographic base. Next, a stratigraphic column was established, reporting formations from the most recent to the oldest. Once the sequence was set, 3D meshes were inserted into the faults within the “Fault System”, where relevant intersection relationships were specified for each structure. The software then utilized this information to generate “Fault Blocks”, that is, model blocks defined by faults and independently editable.

Finally, using the previously mapped polylines as inputs, the stratigraphic boundaries were reconstructed, allowing for the generation of the final model. Additionally, geometric relationships between overlying and underlying units (e.g., onlap contacts, erosional surfaces, dikes, and veins) could be defined. At fault boundaries, stratigraphic horizons were cut and displaced, accurately reflecting the real-world case (see cross-section in Fig. 5c).

Once completed and validated, 3D surfaces of faults, stratigraphic horizons, and volumes, which consist of triangular meshes, were exported from Leapfrog Works into GOCAD Tsurf (.ts) format.

Data Records

The entire dataset, including both the 3D geometries generated through modeling and the input data, is provided as a ZIP file available for download from the dedicated page on the “figshare” repository60. The folder named ‘3D_model_data’ contains eight subfolders that, as described in the repository portal, include the input data used in the modeling process:

-

i)

The ‘Boreholes’ folder contains two.csv files: collar and LA Geology, which contain the geographic coordinates of the hole and the stratigraphy within the boreholes, respectively.

-

ii)

The ‘Geological_cross_sections’ folder contains all the images of the cross-sections used to construct the model, along with a shapefile showing their traces in plain view.

-

iii)

The ‘Seismic_lines’ folder includes images of the seismic lines and the corresponding shapefile of their traces.

-

iv)

The ‘Topography’ folder contains the 5 × 5 m resolution DTM of the Emilia-Romagna Region and two georeferenced seismotectonic maps.

-

v)

The ‘Seismicity’ folder provides.shp and.csv files of the earthquakes recorded up to December 2023, as well as focal mechanism data used for identifying seismogenic faults.

-

vi)

The ‘Stress_field’ folder includes data on the stress field measured at specific locations within the study area.

-

vii)

The ‘3D_objects’ folder includes four.ts files containing all the 3D geometries created. These files are the same as those hosted in the ISPRA geoviewer. The.ts format is compatible with the most common 3D modeling softwares and libraries.

-

viii)

The ‘Attribute_tables’ folder contains the complete Excel spreadsheets submitted to ISPRA to link the attributes of faults, horizons, and volumes to the corresponding 3D surfaces. These tables were created to associate each 3D geometry with key parameters for interactive exploration.

The interactive 3D model can be accessed on ISPRA’s official website (Mappa | ISPRA Geo-IT3D) and an example of visualization is shown in Fig. 6. The metadata can be accessed either through the repository or via the ISPRA viewer, as well as by clicking on the dedicated link (https://metasfera.regione.emilia-romagna.it/ricerca_metadato?uuid=r_emiro:GeoMod3D_RER1).

Views of the 3D model as visualized in the 3Dviewer on the ISPRA website (Visualizzazione 3D | ISPRA Geo-IT3D).

Technical Validation

Image comparison method

The primary model assessment procedure involved visually comparing geological units and faults, as defined by the input data, with their corresponding 3D modeled geometries.

Specifically, the plan view of the 3D seismotectonic model was compared to the original 2D Seismotectonic map48 in Fig. 7a. Additionally, six cross-sections extracted from the 3D model (Fig. 7b) were analyzed. These sections, oriented orthogonally to the main structures and geological boundaries, were directly compared to the original input cross-sections. The slices were generated using the “Slicer tool” in Leapfrog Works (version 2023.2), enabling internal observation of the model. The extracted sections were aligned with and georeferenced to corresponding 2D sections from previous seismotectonic maps48,51, allowing for a nearly direct comparison between the model output and real-world data. In Fig. 7b, the 2D input sections on the right display the polylines for key structures and boundaries, which were mapped and used to construct the geometries on the left. This comparison, both in plain view and cross-section, demonstrates that the software accurately reproduced the input mapped features. Observed differences arise from necessary simplifications, which were intentionally applied to focus on the geology relevant to the seismotectonic context. As noted in previous chapters, only the major faults and stratigraphic horizons that could be confidently correlated across different domains were interpolated and modelled. Consequently, lower-order structures are absent in the model sections (Fig. 7, left) due to their lack of lateral continuity and difficulty to correlate.

Another key consideration when comparing model results with input data is the interpretative component present in some generated cross sections. At times, stratigraphic units were extended beyond the depth constraints of the original 2D sections to bridge knowledge gaps and propose a refined seismotectonic model. This type of validation is feasible in regions where 2D input data are available, whereas the remaining parts of the model are based on interpretation.

Geological validation method

The second method for validating the 3D model involved assessing the accuracy of the reconstructed geometries by using geological literature and fundamental geological principles. This step ensured that the modelled structures were realistic and attributable to actual geological features. For mapped faults, for example, validation focused on verifying whether their reconstruction was both geometrically and kinematically consistent with known thrust-type structures (in the frontal sector of the fold and thrust belt in the Po Plain) and extensional faults (in the inner sector) of the NA chain61,62. Additionally, the geometric, kinematic, and seismological parameters recorded in the attribute tables for each fault were compared against available literature data29, and it was confirmed that the parameters calculated by this model are of the same order of magnitude and comparable to those reported in literature30.

Methodological uncertainties

Any 3D modelling procedure, interpolation method, the sensitivity and precision of an operator when georeferencing and mapping structures, and, above all, the interpretative nature of geological reconstructions, all inevitably introduce uncertainties. Nevertheless, we strived to minimize errors where possible by simplifying the system only where strictly necessary and, as described in the previous sections, by accurately reconstructing the geometries of the main structures. The eastern part of the model is undoubtedly the best constrained and, thus, subject to fewer uncertainties. This applies both to the plain sector, constrained by numerous boreholes and seismic lines, and to the mountainous sector, where extensive fieldwork was carried out. Conversely, the western portion of the model is likely the most affected by interpretative and interpolation-related uncertainties, due to the lower density of available geological data. The subsurface geometry of geological surfaces in data-sparse areas is therefore subject to greater uncertainty; however, consistency was verified by applying fundamental stratigraphic and tectono-stratigraphic principles.

Usage Notes

This section illustrates examples of potential applications of the 3D model, both in educational and teaching contexts, as well as in applied and advanced research fields.

Applications for seismic hazard assessment

The 3D model presented here can serve as a basis for further seismic hazard studies, enabling and facilitating the parameterization of active faults and seismogenic sources in the context of Probabilistic Fault Displacement Hazard Assessment (PFDHA)63 and Probabilistic Seismic Hazard Analysis - PSHA)64,65,66. In addition to the geometric parameters directly measurable from 3D models (fault trace length, orientation, dip direction, average dip, area and volume occupied, minimum and maximum depth, etc.), it is also possible to calculate key parameters such as displacements, slip rates, seismicity distribution, maximum magnitude, and from these, potentially, the recurrence time.

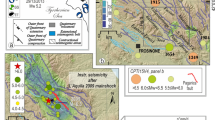

Below is an example of application to a seismogenic thrust oriented along the PAM (Fig. 8a). This example demonstrates the ease with which the seismogenic zone characteristics can be constrained. Geometric parameters of faults, such as dip direction, dip angle, fault trace length, area and maximum and minimum depth, can be obtained by using the measuring tools of Leapfrog Works or by other tools offered by similar softwares.

(a) Instrumental seismicity and focal mechanisms plotted in 3D. A clear distribution in proximity of the mapped faults can be appreciated. (b) Example of serial cross sections along a fault created in Leapfrog Works. (c) 2D map showing the interpolation results and the displacement values calculated along fault strike. (d) Example of a 3D displacement map shown in Leapfrog Works.

To calculate fault displacement and slip rate for a given time interval/chronostratigraphic limit of the model, Leapfrog Works allows creating a series of geological sections, orthogonal to the considered fault, at evenly spaced intervals determined by the lateral dimension of the structure, the completeness of the data, and the required degree of precision (Fig. 8b). This procedure allows the 3D visualization of displacement and its variations along the fault strike by mapping the intersection points between the chronostratigraphic limits and the fault itself, at both the fault hanging wall and footwall. These points contain the three-dimensional coordinates necessary to calculate the three components of the displacement. Once processed, it is possible to export them as a.csv file or other formats and to produce detailed maps of the actual displacement along fault traces (Fig. 8c,d) using, for example, the QGIS software. Slip rates can be calculated along the fault strike by dividing the estimated displacements at each interface by the respective chronostratigraphic age. Other important seismogenic parameters, such as the maximum magnitude, can be derived by means of empirical relationships linking area or fault trace length to magnitude67.

Code availability

Leapfrog Works is a 3D modeling software owned and licensed by Seequent. For this work, version 2023.2 available at the following link was used (https://www.seequent.com/products-solutions/leapfrog-works/). The open-source mapping software QGIS, initially used to georeference the 2D input data, is available at the link (https://qgis.org/it/site/forusers/download.html).

References

Ascione, A., Mazzoli, S., Petrosino, P. & Valente, E. A decoupled kinematic model for active normal faults: Insights from the 1980, MS = 6.9 Irpinia earthquake, southern Italy. GSA Bulletin. 125(7-8), 1239–1259, https://doi.org/10.1130/B30814.1 (2013).

Pantosti, D. & Valensise, G. Faulting mechanism and complexity of the 23 November 1980, Campania-Lucania earthquake, inferred from surface observations. Journal of Geophysical Research 95, 15.319–15.341, https://doi.org/10.1029/JB095iB10p15319 (1990).

Pantosti, D., Schwarr, D. P. & Valensise, G. Paleoseismology along the 1980 surface rupture of the Irpinia fault: implications for earthquake recurrence in the southern Apennines, Italy. Journal of Geophysical Research 98, 6.561–6.577, https://doi.org/10.1029/92JB02277 (1993).

Muir-Wood, R. From global seismotectonics to global seismic hazard. Annals of geophysics 36(3), 153–168, https://doi.org/10.4401/ag-4261 (1993).

Kanamori, H. & Anderson, D. L. Theoretical basis of some empirical relations in seismology. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 65(5), 1073–1095, https://doi.org/10.1785/BSSA0650051073 (1975).

Wells, D. & Coppersmith, K. New Empirical Relationships among Magnitude, Rupture Length, Rupture Width, Rupture Area, and Surface Displacement. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 84(4), 974–1002, https://doi.org/10.1785/BSSA0840040974 (1994).

Cello, G., Mazzoli, S., Tondi, E. & Turco, E. Active tectonics in the central Apennines and possible implications for seismic hazard analysis in peninsular Italy. Tectonophysics 272, 43–68, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-1951(96)00275-2 (1997).

Cinti, F. R., Cucci, L., Marra, F. & Montone, P. The 1997 Umbria-Marche earthquakes (Italy): relations between the surface tectonic breaks and the area of deformation. Journal of Seismology 4, 333–343, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026575219394 (2000).

Galadini, f, Meletti, C. & Vittori, E. Major active faults in Italy: available surficial data. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences 80(3-4), 273–296, https://doi.org/10.1017/S001677460002388X (2001).

Boncio, P., Lavecchia, G. & Pace, B. Defining a model of 3D seismogenic sources for Seismic Hazard Assessment applications: The case of central Apennines (Italy). Journal of Seismology 8, 407–425, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOSE.0000038449.78801.05 (2004).

Galli, P., Galadini, F. & Pantosti, D. Twenty years of paleoseismology in Italy. Earth-Science Reviews 88, 89–117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2008.01.001 (2008).

Picotti, V. & Pazzaglia, F. J. A new active tectonic model for the construction of the Northern Apennines mountain front near Bologna (Italy). J. Geophys. Res. 113, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JB005307 (2008).

Boccaletti, M., Corti, G. & Martelli, L. Recent and active tectonics of the external zone of the Northern Apennines (Italy). International Journal of Earth Sciences 100, 1331–1348, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-010-0545-y (2011).

Faure Walker, J. et al. Fault2SHA Central Apennines database and structuring active fault data for seismic hazard assessment. Scientific Data 8, 87, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00868-0 (2021).

Malagnini, L. et al. Characterization of earthquake-induced ground motion from the L’Aquila seismic sequence of 2009, Italy. Geophys. J. Int. 184, 325–337, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04837.x (2011).

Govoni, A. et al. The 2012 Emilia seismic sequence (Northern Italy): Imaging the thrust fault system by accurate aftershock location. Tectonophysics 622, 44–55, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2014.02.013 (2014).

Vignaroli, G. et al. Spatial-Temporal Evolution of Extensional Faulting and Fluid Circulation in the Amatrice Basin (Central Apennines, Italy) During the Pleistocene. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 1–23, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2020.00130 (2020).

Vignaroli, G. et al. Middle Pleistocene fluid infiltration with 10-15 ka recurrence within the seismic cycle of the active Monte Morrone Fault System (central Apennines, Italy). Tectonophysics 827, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2022.229269 (2022).

Gusmeo, T. et al. Recent and active faulting along the exposed front of the Northern Apennines (Italy): New insights from field and geochronological constraints. Tectonophysics 891, 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2024.230517 (2024).

Technical Commission for Seismic Microzonation, Linee guida per la gestione del territorio in aree interessate da Faglie Attive e Capaci (FAC), versione 1.0. Conferenza delle Regioni e delle Province Autonome – Dipartimento della protezione civile, Roma https://www.protezionecivile.gov.it/static/a466d66cbb6f1aefcbba5a7cdbffbd58/Linee_Guida_Faglie_Attive_Capaci_2016.pdf (2015).

ISPRA-Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale. Modello geologico 3D e geopotenziali della Pianura Padana centrale (Progetto GeoMol). Rapporti ISPRA, 234/2015, pp. 104 e Appendice http://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/pubblicazioni/rapporti/modello-geologico-3d-e-geopotenziali-della-pianura-padana-centrale-progetto-geomol (2015).

Šram, D., Rman, N., Rižnar, I. & Lapanje, A. The three-dimensional regional geological model of the Mura-Zala Basin, northeastern Slovenia, Geologija, 58/2, 139-154 (Ljubljana, GeoZS) http://www.geologija-revija.si/dokument.aspx?id=1254 (2015).

GNS Science. New Zealand Active Faults Database 1:250.000 scale https://www.gns.cri.nz/data-and-resources/new-zealand-active-faults-database (2016).

https://gbank.gsj.jp/activefault/index_e_gmap.html (2025). National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology. 2025. Active Fault Database of Japan, June 17, 2025 version.

Thornton, J., Mariethoz, G. & Brunner, P. A 3D geological model of a structurally complex Alpine region as a basis for interdisciplinary research. Sci Data 5, 180238, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.238 (2018).

D’Ambrogi., C., De Donatis, M., Pantaloni, M. & Borraccini, F. 3D geological model of the sheet 280 Fossombrone (Northern Apennines)- Geological Map of Italy 1:50.000. Mapping Geology in Italy, SELCA (2004).

D’Ambrogi, C., Maesano, F.E., Marino, M., Congi, M.P. & Morrone, S. Geological 3D model of the Po Basin [Data set]. https://doi.org/10.15161/oar.it/76873 (2023).

Di Bucci, D., Buttinelli, M., D’Ambrogi, C. & Scrocca, D. the RETRACE-3D Working Group. RETRACE-3D project: a multidisciplinary collaboration to build a crustal model for the 2016-2018 central Italy seismic sequence. Boll. Geof. Teor. Appl. 62, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.4430/bgta0343 (2021).

Pondrelli, S. European-Mediterranean Regional Centroid-Moment Tensors Catalog (RCMT) [Data set]. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV) https://doi.org/10.13127/rcmt/euromed (2002).

Basili, R. et al. The Database of Individual Seismogenic Sources (DISS), version 3: Summarizing 20 years of research on Italy’s earthquake geology. Tectonophysics 453, 20–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2007.04.014 (2008).

Meletti, C., Montaldo, V., Stucchi, M. & Martinelli, F. Database della pericolosità sismica MPS04 https://data.ingv.it/en/dataset/70#additional-metadata (2004).

IAEA-International Atomic Energy Agency Annual Report for 2010 https://www.iaea.org/publications/reports/annual-report-2010 (2010).

Galli, P. et al. The awakening of the dormant Mount Vettore fault (2016 central Italy earthquake, Mw 6.6): Paleoseismic clues on its millennial silences. Tectonics 38, 687–705, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018TC005326 (2019).

Merla, G. Geologia dell’Appennino Settentrionale: Bollettino della Società. Geologica Italiana 70, 95–382 (1952).

Boccaletti, M., Elter, P. & Guazzone, G. Plate tectonic models for the development of the Western Alps and Northern Apennines. Nature, Phys. Sc. 234, 108–111, https://doi.org/10.1038/physci234108a0 (1971).

Boccaletti, M. et al. Migrating foredeep-thrust belt system in the Northern Apennines and Southern Alps. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology., Palaeoecology 77, 3–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(90)90095-O (1990).

Castellarin, A., Eva, C., Giglia, G. & Vai, G. B. Analisi strutturale del fronte appenninico-padano. Giorn. Geol., ser. 3 47(1-2), 47–76 (1985).

Mantovani, E., Babbucci, D., Tamburelli, C. & Viti, M. A review on the driving mechanism of the Tyrrhenian-Apennines system: implications for the present seismotectonic setting in the Central-Northern Apennines. Tectonophysics 476, 22–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2008.10.032 (2009).

Mantovani, E., Viti, M., Babbucci, D., Tamburelli, C. & Cenni, N. How and why the present tectonic setting in the Apennine belt has developed. Journal of the Geological Society 176, 1291–1302, https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2018-175 (2019).

Jolivet, L. & Faccenna, C. Mediterranean extension and the Africa-Eurasia collision. Tectonics 19, 1095–1106, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000TC900018 (2000).

Bennett, R. A. et al. Syn-convergent extension observed using the RETREAT GPS network, northern Apennines, Italy. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 117 https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JB008744 (2012).

Corradino, M., Balazs, A., Faccenna, C. & Pepe, F. Arc and forearc rifting in the Tyrrhenian subduction system. Scientific Reports 12, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08562-w (2022).

Ricci Lucchi, F. The Oligocene to Recent foreland basins of the northern Apennines. Special Publications of the International Association of Sedimentologists 8, 105–139 (1986).

ITHACA Working Group. ITHACA (ITaly HAzard from CApable faulting), A database of active capable faults of the Italian territory. Version December 2019. ISPRA Geological Survey of Italy. Web Portal: http://sgi.isprambiente.it/ithaca/viewer/index.html (2019).

Elter, P., Grasso, M., Parotto, M. & Vezzani, L. Structural setting of the Apennine-Maghrebian thrust belt. Episodes 26, 205–211, https://doi.org/10.18814/epiiugs/2003/v26i3/009 (2003).

Remitti, F. et al. Tectonic and sedimentary evolution of the frontal part of an ancient subduction complex at the transition from accretion to erosion: The case of the Ligurian wedge of the Northern Apennines, Italy. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 123, 51–70, https://doi.org/10.1130/B30065.1 (2011).

Conti, P., Cornamusini, G. & Carmignani, L. An outline of the geology of the northern Apennines (Italy), with geological map at 1:250,000 scale. Italian Journal of Geosciences 139, 149–194, https://doi.org/10.3301/IJG.2019.25 (2020).

DISS Working Group. Database of Individual Seismogenic Sources (DISS), Version 3.3.0: A compilation of potential sources for earthquakes larger than M 5.5 in Italy and surrounding areas. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV). https://doi.org/10.13127/diss3.3.0 (2021).

Pieri, M. & Groppi, G. Subsurface geological structure of the Po plain, Italy. Publ. n. 414 Prog. Finalizz. Geodinamica 10, 10 (1981).

Boccaletti, M. et al. Considerations on the seismotectonics of the Northern Apennines. Tectonophysics 117, 7–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(85)90234-3 (1985).

Boccaletti, M. et al. Seismotectonic Map of the Emilia-Romagna Region. 1: 250.000 scale. Area Geologia, Suoli e Sismica, Regione Emilia-Romagna, and CNR - Istituto di Geoscienze e Georisorse, Sezione di Firenze https://ambiente.regione.emilia-romagna.it/it/geologia/pubblicazioni/cartografia-geo-tematica/carta-sismotettonica-della-regione-emilia-romagna-in-scala-1-250-000-2004-1 (2004).

Montone, P. & Mariucci, M. T. The new release of the Italian contemporary stress map. Geophysical Journal International 205, 1525–1531, https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggw100 (2016).

Mariucci, M. T. & Montone, P. 2020. Database of Italian present-day stress indicators, IPSI 1.4,. Scientific Data 7, 298, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00640-w (2020).

Mariucci, M. T. & Montone, P. IPSI 1.5, Database of Italian Present-day Stress Indicators. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV) https://doi.org/10.13127/IPSI.1.5 (2022).

Bell, J. S. & Gough, D. I. Northeast-southwest compressive stress in Alberta: evidence from oil wells,. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 45, 475–482, https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821X(79)90146-8 (1979).

Zoback, M. D., Moos, D., Mastin, L. & Anderson, R. N. Well bore breakouts and in situ stress. J. Geophys. Res. 90(B7), 5523–5530, https://doi.org/10.1029/JB090iB07p05523 (1985).

ISIDe Working Group. Italian Seismological Instrumental and Parametric Database (ISIDe). Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV). https://doi.org/10.13127/ISIDe (2007).

Rovida, A., Locati, M., Camassi, R., Lolli, B. & Gasperini, P. The Italian earthquake catalogue CPTI15. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 18(7), 2953–2984 (2020).

Rovida, A. et al. Catalogo Parametrico dei Terremoti Italiani (CPTI15), versione 4.0. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV) https://doi.org/10.13127/CPTI/CPTI15.4 (2022).

Carloni, G. et al. MOD_SISM_RER - A new 3D seismotectonic model of the Northern Apennines Pedeapenninic margin for Seismic Hazard Assessment. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29437256.v2 (2025).

Anderson, E. M. The Dynamics of Faulting. Transactions of the Edinburgh Geological Society 8, 387–402 (1951).

Fossen, H. Structural Geology. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781107415096 (2016).

Youngs, R. R. et al. A methodology for probabilistic fault displacement hazard analysis (PFDHA). Earthq. Spectra 19, 191–219, https://doi.org/10.1193/1.1542891 (2003).

Valentini, A., Visini, F. & Pace, B. Integrating faults and past earthquakes into a probabilistic seismic hazard model for peninsular Italy. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 17, 2017–2039 https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-17-2017-2017 2017 (2017).

Valentini, A., Boncio, P., Visini, F., Pagliaroli, A. & Pergalani, F. Definition of Seismic Input From Fault-Based PSHA: Remarks After the 2016 Central Italy Earthquake Sequence. Tectonics 38, 595–620, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018TC005086 (2019).

Stirling, M. W. The continued utility of probabilistic seismic-hazard assessment. In Hazards and Disasters Series, Earthquake Hazard, Risk and Disasters, 359–376 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394848-9.00013-4 (2014).

Leonard, M. Earthquake fault scaling: Self-consistent relating of rupture length, width, average displacement, and moment release. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 100(5A), 1971–1988, https://doi.org/10.1785/0120090189 (2010).

Martelli, L. et al. Carta Sismotettonica della Regione Emilia- Romagna e aree limitrofe. Scala 1:250.000 https://ambiente.regione.emilia-romagna.it/it/geologia/pubblicazioni/cartografia-geo-tematica/carta-sismotettonica-della-regione-emilia-romagna-e-aree-limitrofe-edizione-2016 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA) for hosting our 3D model in their repository. We would like to express our special gratitude to the entire Deformation, Fluids, and Tectonics (DFT) group of the Department of Biological, Geological, and Environmental Sciences in Bologna for their comments and constructive discussions during the development of this project. We thank Dr. Marica Landini (Geological Survey of the Emilia-Romagna Region) for her technical support in creating the metadata and depositing the dataset in the repository. Finally, we thank Dr. Francesco Visini and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments, and the Senior Editor, Dr. Elizabeth Miller, for careful handling of our submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Giacomo Carloni: Writing - original draft, editing, 3D model creation, Data curation. Luca Martelli: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Alberto Martini: 3D model editing, Data curation and Storage, Thomas Gusmeo: Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Gianluca Vignaroli: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Giulio Viola: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carloni, G., Martelli, L., Martini, A. et al. A new 3D seismotectonic model of the Northern Apennines Pedeapenninic margin for seismic hazard assessment. Sci Data 12, 1616 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05835-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05835-7