Abstract

Hippophae salicifolia, a dioecious small tree species endemic to the Himalayan region, holds great potential in both ecological conservation and industrial applications. In this study, we employed PacBio HiFi long reads, Illumina short reads, and Hi-C technology to construct a high-quality, chromosome-level reference genome. The assembled genome is approximately 1.11 Gb in size, with a scaffold N50 of 95.29 Mb, and 99.94% of the sequences were successfully anchored to 12 pseudo-chromosomes. A total of 42,547 protein-coding genes were predicted, and approximately 85% of these genes obtained functional annotations. Repetitive elements constituted about 45.25% of the genome, with Long Terminal Repeat (LTR) being the most abundant (32.54%). BUSCO analysis indicated that both the assembly and annotation are highly complete. This high-quality genomic resource provides a valuable foundation for investigating sex determination mechanisms, adaptive evolution, and genomic diversity in H. salicifolia and related species, as well as for advancing genetic improvement, resource conservation, and utilization efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The genus Hippophae (family Elaeagnaceae) is broadly distributed across the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and its adjacent regions. Members of this genus exhibit remarkable adaptability to harsh environments, including drought, cold, salinity, and nutrient-poor soils1,2. Furthermore, Hippophae species can form nitrogen-fixing root nodules with Frankia bacteria2,3, thereby improving soil conditions. Through clonal propagation via root suckers, they can establish stable vegetation communities and effectively mitigate soil erosion. Moreover, their fruits provide a vital food source for various wild animals, thereby contributing to the maintenance of ecosystem diversity. Beyond their ecological significance, these species hold substantial potential for applications in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. Their fruits and leaves are particularly rich in vitamin C, flavonoids, essential fatty acids, and various secondary metabolites, which exhibit potential antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and cardiovascular protective activities1,2,4.

Hippophae salicifolia D. Don, a dioecious deciduous tree named for its willow-like leaves5, is primarily distributed along riverbanks, slopes, and shrublands on the southern slopes of the Himalayas, including southeastern Tibet in China, as well as regions in Nepal, Bhutan, and northern India6. Previous studies have indicated that Hippophae species possess an XY sex determination system (2n = 24)7,8,9,10. Elucidating the mechanisms underlying sex determination and dioecy in Hippophae is crucial for gaining deeper insight into its adaptive evolution in the unique environment of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. However, research on sex-related differences in dioecious Hippophae species remains notably limited. Most previous studies have focused on chromosome-level genomes11,12,13,14,15,16, chloroplast genomes17,18,19, mitochondrial genomes20,21, sex-specific molecular markers7,9,10,22,23, fruit nutrient content24,25, and transcriptomes26,27. With advancements in third-generation sequencing technologies (e.g., PacBio HiFi), which offer higher accuracy and throughput at reduced costs28,29, it is now feasible to generate high-quality reference genomes for non-model species such as H. salicifolia, thereby facilitating comprehensive investigations into sex determination and adaptive evolution.

To date, several Hippophae species have been successfully assembled at the genome level, including H. rhamnoides11,12,13, H. tibetana15,16, and H. gyantsensis14. These genomic resources have substantially advanced our understanding of gene diversity, phylogenetics, adaptive evolution, and sex determination mechanisms within the genus. Nonetheless, genomic research on H. salicifolia remains scarce, hindering systematic insights into its genetic background, evolutionary status, and sex determination processes.

In the present study, we employed PacBio HiFi long-read sequencing, Illumina short-read sequencing, and Hi-C data to generate a high-quality, chromosome-level reference genome of H. salicifolia. The assembled genome is approximately 1.11 Gb in size, with a scaffold N50 of 95.29 Mb (Table 1), and 99.4% of the sequences were successfully anchored to 12 putative chromosomes. A total of 42,547 genes were predicted, with repetitive elements accounting for approximately 45.25% of the genome. This is the first high-quality reference genome for H. salicifolia, thereby providing crucial data for elucidating sex determination mechanisms, genome evolution, and adaptive evolution within the genus. Moreover, it lays a robust scientific foundation for future research in genetic improvement, resource conservation, and sustainable utilization of Hippophae species.

Methods

Sample collection and sequencing

In June 2024, samples of a female individual (XX) of H. salicifolia were identified and collected by La Qiong and Junwei Wang in the Lebu Valley Scenic Area of Cuona County, Shannan City, Tibet (27°55′25.98″ N, 91°48′49.62″ E) (Fig. 1a). A voucher specimen (No. LQ20240672) was deposited in the Herbarium of the College of Ecology and Environment, Xizang University. To ensure the acquisition of high-quality DNA and RNA, fresh young leaves and bark tissues were collected and promptly flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen on-site, followed by storage at –80 °C in the laboratory. Genomic DNA was extracted using a modified CTAB method30, and its purity and concentration were measured using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and Qubit 2.0 (Invitrogen, USA). Integrity was assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Only DNA samples that satisfied the quality criteria were selected for subsequent library construction and sequencing.

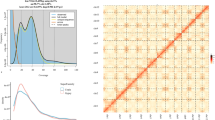

Genome survey of H. salicifolia. (a) Photograph of the H. salicifolia plant. (b) K-mer (k = 21)-based genome size estimation. The blue region depicts the observed 21-mer frequency distribution; the black curve illustrates the fitted model, and yellow and red portions correspond to unique and erroneous K-mer distributions, respectively.

High-quality genomic DNA was sheared into fragments of approximately 350 bp to construct Illumina sequencing libraries used for an initial genome survey. Library quality was verified using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and quantitative PCR. Paired-end sequencing (150 bp) was conducted on the Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform, yielding approximately 62.78 Gb of high-quality short-read data. These short reads were primarily utilized to estimate genome size, GC content, and heterozygosity (Table 2). To obtain a high-accuracy de novo genome assembly, PacBio Sequel II was employed for HiFi sequencing. DNA was sheared into large fragments of 15–20 kb, and the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 was applied to construct HiFi libraries. Approximately 31.80 Gb of HiFi data were obtained, with an average read length of 15.94 kb and a sequencing depth of about 28.69× (Table 2).

To achieve a chromosome-level assembly, high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technology was employed. Fresh leaf tissues were fixed in formaldehyde and digested with the restriction enzyme MboI, then subjected to ligation and purification to construct Hi-C libraries. Libraries that passed quality checks underwent sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform (150 bp paired-end), generating approximately 102.43 Gb of Hi-C data (Table 2).

In addition, to support gene structure annotation and functional analysis, total RNA was extracted from leaves and bark of H. salicifolia to construct transcriptome libraries. The resulting libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform using 150 bp paired-end reads, generating approximately 8 Gb of transcriptome data per sample (Table 3). These transcriptomic resources provide valuable data for subsequent gene prediction and functional annotation.

Genome size estimation and survey analysis

Using high-quality Illumina short-read data, a k-mer analysis was performed to estimate the genome size, heterozygosity, and proportion of repetitive sequences in H. salicifolia. First, raw reads were processed with fastp v0.20.031 to remove adapter contamination and low-quality reads. Next, Jellyfish v2.2.1032 was utilized to count the distribution of 21-mer frequencies, and GenomeScope v2.033 was employed to estimate genome characteristics. These analyses indicated that the H. salicifolia genome size is approximately 1.05 Gb, with a heterozygosity of about 0.49% (Fig. 1b).

Genome assembly

The H. salicifolia genome was de novo assembled using high-quality HiFi long-read data with hifiasm v0.19.934. Hifiasm was executed with default parameters to fully exploit the high accuracy and long fragment lengths of the HiFi data, resulting in a highly continuous initial assembly. Subsequently, Illumina short-read data were integrated for assembly polishing. Specifically, BWA-MEM v2.2135 was applied to map quality-controlled Illumina reads back to the initial assembly, followed by two rounds of error correction with Pilon v1.2436 (“–fix all”) to address potential base errors and fill small gaps, thereby enhancing the assembly’s accuracy and completeness.

To achieve a chromosome-level genome assembly, Hi-C data were integrated to further optimize the polished assembly. First, Juicer v2.037 was employed to preprocess and map the Hi-C reads to the corrected genome. Then, 3D-DNA38 was executed with default parameters to scaffold the assembly, followed by manual inspection and adjustment in Juicebox v2.15.0739 to ensure accuracy and integrity at the chromosome scale. Based on previously published H. rhamnoides genome information10, the chromosomes were designated as Chr01 through Chr12. The final chromosome-level assembly has a total length of 1.11 Gb, with a scaffold N50 of 95.29 Mb, a contig N50 of 38.57 Mb, and an L50 of 5, containing a total of 210 gaps and exhibiting a GC content of 29.76% (Table 1). Approximately 99.94% of the assembled sequences were successfully anchored onto 12 putative chromosomes (Table 4). The Hi-C interaction matrix revealed clear intra-chromosomal signals along the diagonal (Fig. 2), indicating a high level of continuity and accuracy, thus providing a robust foundation for subsequent gene annotation and functional analyses.

Repeat annotation

To comprehensively characterize the repetitive elements in the H. salicifolia genome, de novo repeat prediction was conducted using RepeatModeler v2.0.140 (http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler/) to establish a species-specific repeat library. This customized library was subsequently merged with the RepBase database41 (v20181026, http://www.girinst.org/repbase). The combined library served as input to RepeatMasker v4.1.042 (http://www.repeatmasker.org) for the identification and masking of repetitive sequences. RepeatMasker identifies and annotates repetitive elements by comparing sequences to a curated transposable element (TE) library, which defines the classification based on sequence similarity and structural features, including major types such as LTR, LINE, SINE, and DNA transposons.

The annotation indicated that the total length of repetitive sequences was approximately 501.59 Mb, representing 45.25% of the entire genome (Table 5). Among these, LTR retrotransposons comprised the highest proportion (32.54%, ~360.72 Mb), while DNA transposons (4.01%, ~44.50 Mb) and LINE elements (0.45%, ~4.97 Mb) were also present (Table 5). This comprehensive repetitive element profile provides a valuable foundation for investigating genome evolution, structural variation, and gene regulatory mechanisms.

Protein-coding gene prediction and functional annotation

To obtain a high-quality set of protein-coding genes, three complementary strategies were integrated: homology-based prediction, transcriptome-based prediction, and ab initio prediction. First, for homology-based prediction, protein sequences from sequenced Hippophae species (e.g., H. rhamnoides, H. tibetana, and H. gyantsensis) were aligned to the H. salicifolia genome using GeMoMa v1.943 to identify potential orthologous genes. Second, for transcriptome-based prediction, RNA-seq data from leaf and bark tissues were assembled into transcripts using stringtie v2.1.344, and coding regions were predicted using TransDecoder v5.1.0 (https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder). Lastly, ab initio predictions were performed with AUGUSTUS v3.3.345 (https://github.com/Gaius-Augustus/Augustus), GlimmerHMM v3.0.446, and GeneMark-ES v4.3847. Species-specific parameters were applied to improve prediction accuracy. All these predictions were integrated using EVidenceModeler (EVM) v1.1.148 to generate a high-confidence gene set, and PASA v2.5.249 (https://github.com/PASApipeline/PASApipeline) was subsequently employed for further refinement, adding UTR information and identifying novel transcripts. In total, 42,547 protein-coding genes were predicted, with an average gene length of 3,663 bp and an average of 4.72 exons per gene (Table 6). TBtools v2.12650 was utilized to visualize gene density, GC content, Gypsy and Copia element densities, and chromosomal synteny of the 12 chromosomes (Fig. 3).

To gain comprehensive insights into gene functions, functional annotation was performed by conducting BLASTp51 searches (E-value ≤ 1e–5) against multiple databases, including the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)52, euKaryotic Orthologous Groups (KOG), the National Center for Biotechnology Information Non-Redundant database (NCBI-NR, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Gene Ontology (GO)53, Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG)54, and SwissProt55. Additionally, HMMER v3.2.1 was employed, along with the Pfam database, to predict protein domains. Approximately 85.06% of the genes (36,189 genes) were functionally annotated in at least one database, thus providing a solid basis for subsequent functional genomics research (Table 7).

Non-Coding RNA annotation

To identify non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in the H. salicifolia genome, multiple tools and databases were integrated. A total of 748 tRNA genes were detected using tRNAscan-SE v2.0.0 (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/)56 (Table 8). Using the Rfam v14.2 database57 and Infernal v1.1.358, 5,924 rRNA genes, 196 miRNA genes, and 5,950 snRNA genes were identified. These ncRNA annotations will facilitate studies on transcriptional regulation and the functional mechanisms underlying the H. salicifolia genome.

Genome-wide synteny analysis

The Python version of MCScan implemented in JCVI v1.2.7.5259 (default parameters) was employed to examine genomic synteny between H. salicifolia and its close relatives. The resulting synteny maps support the assessment of structural accuracy and completeness of the assembled genome through comparative analysis (Fig. 4).

Data Records

The raw sequencing data have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under accession number SRP54855360, including PacBio HiFi reads, Illumina PE150 reads, Hi-C reads, and RNA-seq data from various tissues. The final chromosome-scale assembled genome has been deposited in the NCBI GenBank under accession number JBJWFA00000000061. In addition, the genome assembly and annotation files have been stored in the Figshare database62.

Technical Validation

Several strategies were employed to assess the quality of the genome. The completeness of the non-redundant draft genome was evaluated using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO v5.4.5)63 with the embryophyta odb10 dataset (1,614 single-copy genes) under default parameters. At the assembly level, BUSCO analysis showed that 98.8% of BUSCO genes were complete (89.8% single-copy, 9.0% duplicated), with only 0.4% fragmented and 0.8% missing (Table 9). At the annotation level, 99.3% of BUSCO genes in the predicted protein-coding gene set were complete (70.6% single-copy, 28.7% duplicated), with only 0.1% fragmented and 0.6% missing. These findings indicate that both the assembly and annotation are highly complete, meeting the standards of a high-quality reference genome.

To validate the accuracy and completeness of the assembly, both Illumina short reads and PacBio HiFi long reads were mapped back to the assembled reference genome. Using BWA-MEM v2.2132, 97.82% of Illumina reads aligned successfully. With Minimap2 v2.1764, the mapping rate of PacBio HiFi reads reached 98.53%. These high mapping rates reinforce the accuracy and completeness of the assembled genome.

We further assessed the base-level consensus accuracy of the assembled genome using Merqury v1.365, based on 21-mers derived from Illumina short reads. Merqury calculated the consensus quality value (QV) for each chromosome individually. The QV scores ranged from 36.22 to 38.80 across all 12 chromosomes, corresponding to base-level error rates between 1.32 × 10−4 and 2.39 × 10−4, or approximately one error per 750 to 1,500 bases (Table 10). These results demonstrate high base-level accuracy in the genome assembly.

In addition, a k-mer spectra-cn plot was generated (Fig. 5) to visualize the multiplicity distribution of 21-mers from Illumina reads compared to their presence in the assembly. The plot exhibited a dominant peak centered around multiplicity 50, with very few low-frequency or missing k-mers. This indicates that the vast majority of high-quality k-mers from the raw reads were accurately incorporated into the assembly, further supporting its high completeness and low redundancy.

K-mer spectra-cn plot generated by Merqury showing the distribution of 21-mers from Illumina reads according to their copy number in the assembly. The dominant red peak (~multiplicity 50) represents k-mers that appear once in the assembly, indicating well-represented unique sequences. Gray areas (read-only) correspond to k-mers present in the reads but absent in the assembly, reflecting sequencing errors or unassembled regions. The low abundance of blue (copy = 2) and other multi-copy k-mers suggests low redundancy and high assembly accuracy.

Code availability

No custom scripts were utilized in this study. All data processing commands and pipelines were executed in strict accordance with the manuals and protocols provided by each bioinformatics software tool.

References

Ciesarová, Z. et al. Why is sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) so exceptional? A review. Food Res. Int. 133, 109170 (2020).

Nybom, H., Ruan, C. & Rumpunen, K. The Systematics, Reproductive Biology, Biochemistry, and Breeding of Sea Buckthorn—A Review. Genes 14, 2120 (2023).

Huss‐Danell, K., Roelofsen, W., Akkermans, A. D. & Meijer, P. Carbon metabolism of Frankia spp. in root nodules of Alnus glutinosa and Hippophaë rhamnoides. Physiol. Plant. 54, 461–466 (1982).

Suryakumar, G. & Gupta, A. Medicinal and therapeutic potential of Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.). J. Ethnopharmacol. 138, 268–278 (2011).

Pant, M., Lal, A. & Rani, A. Hippophae salicifolia D. Don–A plant with multifarious benefits. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 6, 37–40 (2014).

Jia, D. R. & Bartish, I. V. Climatic changes and orogeneses in the Late Miocene of Eurasia: The main triggers of an expansion at a continental scale? Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1400 (2018).

Zeng, Z. et al. Development and validation of sex-linked molecular markers for rapid and accurate identification of male and female Hippophae tibetana plants. Sci. Rep. 14, 19243 (2024).

Puterova, J. et al. Satellite DNA and transposable elements in seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides)., a dioecious plant with small Y and large X chromosomes. Genome Biol. Evol. 9, 197–212 (2017).

Zeng, Z. et al. Development of sex-specific molecular markers for early sex identification in Hippophae gyantsensis based on whole-genome resequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 1187 (2024).

Zeng, Z. et al. Development and application of sex-specific indel markers for Hippophae salicifolia based on third-generation sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 25, 692 (2025).

Yu, L. et al. Genome sequence and population genomics provide insights into chromosomal evolution and phytochemical innovation of Hippophae rhamnoides. Plant Biotechnol. J. 20, 1257–1273 (2022).

Wu, Z. et al. Genome of Hippophae rhamnoides provides insights into a conserved molecular mechanism in actinorhizal and rhizobial symbioses. New Phytol. 235, 276–291 (2022).

Yang, X. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Hippophae rhamnoides variety. Sci. Data. 11, 776 (2024).

Chen, M. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Hippophae gyantsensis. Sci. Data. 11, 126 (2024).

Wang, R. et al. How to survive in the world’s third poplar: Insights from the genome of the highest altitude woody plant, Hippophae tibetana (Elaeagnaceae). Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1051587 (2022).

Zhang, G. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Hippophae tibetana provides insights into high-altitude adaptation and flavonoid biosynthesis. BMC biol. 22, 82 (2024).

Zhou, W., Dong, Q., Wang, H. & Hu, N. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Hippophae tibetana. Mitochondrial DNA B 5, 593–594 (2020).

Wang, L., Wang, J., He, C., Zhang, J. & Zeng, Y. Characterization and comparison of chloroplast genomes from two sympatric Hippophae species (Elaeagnaceae). J. For. Res. 32, 307–318 (2021).

Zhang, Q., Li, J., Yu, Y. & Xu, H. A new map of the chloroplast genome of Hippophae based on inter-and intraspecific variation analyses of 13 accessions belonging to eight Hippophae species. Braz. J. Bot. 46, 367–382 (2023).

Zeng, Z. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of Hippophae tibetana: insights into adaptation to high-altitude environments. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1449606 (2024).

Zeng, Z. et al. Assembly and Comparative Analysis of the Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Hippophae salicifolia. Biology 14, 448 (2025).

Sharma, A., Zinta, G., Rana, S. & Shirko, P. Molecular identification of sex in Hippophae rhamnoides L. using isozyme and RAPD markers. Forestry Studies in China 12, 62–66 (2010).

Zhou, W. et al. Molecular sex identification in dioecious Hippophae rhamnoides L. via RAPD and SCAR markers. Molecules 23, 1048 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Phytochemistry, health benefits, and food applications of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.): A comprehensive review. Front. Nutr. 9, 1036295 (2022).

Ma, Q. G. et al. Hippophae rhamnoides L.: A comprehensive review on the botany, traditional uses, phytonutrients, health benefits, quality markers, and applications. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 71, 4769–4788 (2023).

Liang, J., Zhang, G., Song, Y., He, C. & Zhang, J. Targeted metabolome and transcriptome analyses reveal the pigmentation mechanism of Hippophae (sea buckthorn). fruit. Foods 11, 3278 (2022).

Cui, M., Hu, P., Wang, T., Tao, J. & Zong, S. Differential transcriptome analysis reveals genes related to cold tolerance in seabuckthorn carpenter moth, Eogystia hippophaecolus. PLoS One 12, e0187105 (2017).

Metzker, M. L. Sequencing technologies—the next generation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 31–46 (2014).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Genome assembly in the telomere-to-telomere era. Nat. Rev. Genet. 25, 658–670 (2024).

Sahu, S. K., Thangaraj, M. & Kathiresan, K. DNA extraction protocol for plants with high levels of secondary metabolites and polysaccharides without using liquid nitrogen and phenol. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2012, 1–6 (2012).

Chen, S. Ultrafast one‐pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using fastp. Imeta 2, e107 (2023).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011).

Vurture, G. W. et al. GenomeScope: fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics 33, 2202–2204 (2017).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Jung, Y. & Han, D. BWA-MEME: BWA-MEM emulated with a machine learning approach. Bioinformatics 38, 2404–2413 (2022).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PloS One 9, e112963 (2014).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. PNAS 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Bao, W., Kojima, K. K. & Kohany, O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mobile DNA 6, 1–6 (2015).

Tarailo‐Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current protocols in bioinformatics 25, 4–10 (2009).

Keilwagen, J., Hartung, F., Paulini, M., Twardziok, S. O. & Grau, J. Combining RNA-seq data and homology-based gene prediction for plants, animals and fungi. BMC Bioinf. 19, 1–12 (2018).

Kovaka, S. et al. Transcriptome assembly from long-read RNA-seq alignments with StringTie2. Genome Biol. 20, 1–13 (2019).

Stanke, M., Schöffmann, O., Morgenstern, B. & Waack, S. Gene prediction in eukaryotes with a generalized hidden Markov model that uses hints from external sources. BMC Bioinf. 7, 1–11 (2006).

Majoros, W. H., Pertea, M. & Salzberg, S. L. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics 20, 2878–2879 (2004).

Lomsadze, A., Ter-Hovhannisyan, V., Chernoff, Y. O. & Borodovsky, M. Gene identification in novel eukaryotic genomes by self-training algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 6494–6506 (2005).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 9, 1–22 (2008).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–5666 (2003).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol Plant. 16, 1733–1742 (2023).

Chen, Y., Ye, W., Zhang, Y. & Xu, Y. High speed BLASTN: an accelerated MegaBLAST search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 7762–7768 (2015).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29 (2000).

Tatusov, R. L., Koonin, E. V. & Lipman, D. J. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science 278, 631–637 (2000).

Boeckmann, B. et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 365–370 (2003).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964 (1997).

Griffiths-Jones, S. et al. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D121–D124 (2005).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

Tang, H. et al. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science 320, 486–488 (2008).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP548553 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_046201785.1 (2024).

Zeng, Z. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Hippophae salicifolia. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27987659.v3 (2024).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 21, 245 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Projects of Xizang Autonomous Region, China (Project Nos. XZ202402ZD0005, XZ202402ZY0023, and XZ202402JX0003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Q., W.L., W.Z., J.W. and Z.Z. conceived and designed the study. C.M., J.Z., M.X., and Z.T. prepared the materials, conducted the experiments, and contributed to the data collection. Z.Z. performed the data analysis, prepared the initial draft of the manuscript, and managed the figures and tables. J.W., W.Z., and L.Q. reviewed and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors participated in improving the manuscript and unanimously approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Z., Mao, C., Zhang, J. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Hippophae salicifolia. Sci Data 12, 1503 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05844-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05844-6