Abstract

Using in situ observational data is an important way to study the Arctic environment. However, due to the high-latitude seasonal variation, in situ observations in this region are relatively sparse. To maximize the use of in situ observations, we assemble an Arctic Ocean thermohaline dataset (AOTD) including 414221 available temperature and salinity profiles for the period 1983–2023, with observations from the Chinese Arctic Research Expedition and public data from other databases and observations plans such as the International Polar Year. Also, a unified quality control method is discussed, and strict quality control is applied to these profiles. A gridded dataset of climatological monthly mean temperature, salinity, and Ocean Heat Content derived from an objective analysis of profiles is also presented. The climatology has a horizontal resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°, with 57 vertical layers spanning the 0–1500 m depth range, can help us better understand the Arctic Ocean. AOTD climatology offers importance for the research on thermodynamic processes, spatial and temporal variability of water masses, and oceanic structures in the Arctic Ocean.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The Arctic Ocean is the world’s smallest ocean basin, with an area of approximately 14 million km2 and an average depth of about 1,225 m1. The deepest point of the Nansen Basin—and the Arctic Ocean as a whole—is 5,449 m2. This region exchanges water with other oceans mainly through the Bering Strait, Fram Strait and Barents Sea, while the Canadian archipelago is an additional water channel through which it exchanges water with the rest of the world3. The Arctic sea ice shows an obvious characteristics of seasonal variation4. Global warming caused by climate change has prolonged the ice-free season throughout the Arctic5. As a result, in summer the expanded open waters may absorb more heat into the oceanic mixed layer, causing ocean temperatures to rise and delaying autumn freeze-up5,6. Therefore, the significant exchange of heat and moisture from the ocean to the atmosphere leads to intensified winter warming in the lower troposphere of the Arctic7. This amplification effect of the Arctic7,8 will also have profound impacts on global ocean circulation, sea ice variation, and other phenomena7,9,10.

The unique environmental characteristics of the Arctic make in situ marine environment surveys more challenging than other oceans, and to understand the ice‒sea thermodynamic processes in this area, many observations are required to ensure sufficient spatial and temporal coverage for studying ice–ocean feedback processes in the Arctic. These observations help capture the variability and complexity of oceanographic conditions under changing sea ice conditions. For a long time, a series of observation plans in multiple countries have included in situ observations of ocean elements in the Arctic Ocean. Some examples are as follows: The data of Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS) covers in situ observations of ocean temperature, salinity, flow velocity, meteorological conditions, and other aspects in multiple regions11. The World Ocean Database (WOD) is the world’s largest, most standardized, quality-controlled and freely-available collection of ocean profile data, providing important data resources for research on the long-term and historical characteristics of oceanography, climatology and environmental research fields12. The World Ocean Atlas (WOA) is an objective analysis of climatology based on WOD data, including a series of ocean physical variables such as temperature and salinity, and it has a wide range of applications in oceanography13. WOA18 is a WOA product released in 2018.The Array for Real-time Geostrophic Oceanography (Argo) observation program also covers some Arctic waters14. Specifically, for the coupling between the Arctic atmosphere, sea ice and water, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution conducted observations under the Arctic ice using an Ice-Tethered Profiler (ITP), helping to fill the gap in Arctic Ocean observations15. In addition, Arctic research expeditions by various countries and intergovernmental cooperatives have also generated a series of new Arctic Ocean observations16.

China has accumulated more than 20 years of experience in scientific exploration of the Arctic marine environment. With the support of polar icebreakers Xuelong and Xuelong-217, China has completed comprehensive surveys of the central Arctic Ocean and surrounding seas, carried out a series of scientific investigations in certain sea areas for special phenomena, accumulated a certain amount of first-hand in situ observations.

The environmental characteristics of the Arctic Ocean make it difficult to obtain large amounts of in situ observations. Moreover, the presence of sea ice and other features results in varying quality of the observation data, thus requiring unified quality control and evaluation of data from different sources18,19. Behrendt et al.20 collected temperature and salinity observations from 1980 to 2015 and conducted detailed quality control, including XBT data with only temperature profiles.

With the advancement of observational technologies, in situ observational datasets on a global scale have become increasingly abundant. However, due to the harsh navigation conditions in the Arctic region, some global observational datasets do not include the Arctic or pan-Arctic seas. To date, the internationally recognized Arctic Ocean climatology products include the PHC21 developed by University of Washington and the earlier EWG climatology22, which was compiled from Arctic observations conducted by Russia, the United States, and other countries. The EWG climatology is particularly valuable as it includes Russian observations of the Arctic, greatly enriching the data coverage along the Russian coastline. The PHC climatology incorporates data from the EWG and has been widely adopted by many Arctic models as an initial field.

In addition to climatological products that reflect average conditions over a specific period, observational data are also assimilated into models to produce reanalysis datasets. Whether it’s the globally scaled ORA5 product released by ECMWF based on the NEMO model23, or regional Arctic reanalyses like ASTE_R124, all require the assimilation of vast amounts of observational data to correct model errors.

In this study, thermohaline observation profile from 1983 to 2023 in the Arctic Ocean (60°N–90°N, 180°W–180°E) were collected, including those from the Chinese Arctic Research Expedition over the years. With a series of quality control techniques to eliminate invalid data, we obtained AOTD. To assess the quality of AOTD, we conducted an analysis of the circulation characteristics across the entire Arctic based on the circulation features of the Arctic Ocean, and then, selected five typical sea areas for water mass structure analysis. The results suggest that AOTD has a high quality, and effectively reflects the overall hydrological characteristics of the Arctic Ocean. The release of AOTD has further enriched the pool of assimilable data available for the Arctic region.

On this basis, the arctic ocean thermohaline dataset AOTD climatology was constructed using objective analysis methods, and compared with WOA18 for evaluation. Additionally, we also evaluated the reliability of AOTD climatology AOTD climatology from the perspective of OHC. The AOTD climatology spans the period from 1983 to 2023 and supplements PHC and EWG with more recent observational data.

As indicated by the results, AOTD climatology AOTD climatology can generally reflect the temperature–salinity structure of the Arctic Ocean. However, due to the differences in the data and methods used, there are some differences between AOTD climatology and WOA18 in the upper layers, which is particularly evident in March, when the salinity deviation exceeds the temperature deviation.

As the first version of the Polar Regional Climate State, AOTD climatology still has more improvements in its observation and objective analysis methods, specifically reflected in its relatively high overall temperature. Next, we will update the observation data and analysis methods based on AOTD to better characterize the thermohaline environment of the Arctic Ocean. At the same time, we will also use AOTD climatology as the background field and combine satellite observation data to reconstruct the three-dimensional thermohaline structure of the Arctic Ocean.

Methods

Data collection

AOTD covers the time span of 1983 to 2023. The reason for choosing this period is that, prior to 1983, there were few hydrological observations in the Arctic region, especially in the central area (Fig. 4b), AOTD climatology should be created using in situ observations with high spatial and temporal density including observational programs or datasets from a variety of sources. All data sources are detailed in Table 1. It is worth mentioning that this study also references data obtained from scientific expeditions such as the Xuelong and Xuelong-2 in the Arctic. The basis of AOTD is original observations, so we did not include datasets that have undergone strict quality control. In this paper, a total of 1,453,232 profiles were collected and organized within the aforementioned time frame. Xuelong and Xuelong-2 Research Expedition (Fig. 4d) primarily focuses on areas such as the Bering Strait and Chukchi Sea, where there is a scarcity of data available internationally. This focus has to some extent enhanced the spatial completeness and continuity of the dataset established in this paper for the Arctic Ocean.

Additionally, the results of WOA18 with a horizontal resolution of 0.25 × 0.25°, 57 vertical levels and monthly data are utilized for comparison with the climatology product presented in this paper.

Quality control of the observations

The quality control standards for observation data collected from different sources are not uniform, and there are objective errors in the observation process, which is not conducive to establishing standardized data for use. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct unified quality control25 and screening for these data. First, a rigorous deduplication process was performed on the original data collected from various sources to eliminate duplicate observations. The method used for deduplication in this paper involves a spatial error margin of 0.1° × 0.1° and temporal error margin of 5 hours. Data within this spatiotemporal range are considered duplicates by default, and treated as such in the data processing. It should be noted that although the duplicate elimination algorithm is intended to retain only the highest-quality profiles among repeated measurements, it may, in some cases, lead to the unintended removal of good, unique data. For example, certain ITPs perform profiling more frequently than every 6 hours, and shallow CTD profiles from specific stations may exhibit minor yet meaningful variations. Such profiles could be mistakenly eliminated by the filtering criteria. Some data from the observation instruments of Xuelong and Xuelong-2 directly has undergone visual QC. In order to avoid subjective bias across multiple data sources, visual quality control (QC) was not used in this study, which may lead to the unintended exclusion of correctly configured files.

Quality control plays a crucial role in ensuring the proper use of observation data. In general, quality control can be divided into near real-time QC26,27 (NRQC) and delayed mode QC28,29 (DMQC).NRQC refers to the preliminary quality control conducted immediately after the observation data are acquired, with a delay typically ranging from 1 hour to 1 week. In contrast, DMQC employs more standardized and stringent techniques to conduct a more in-depth quality assessment of observation data, thus requiring more time, typically being delayed by 6 to 12 months.

The seawater properties in the Arctic region differ significantly from those in the open oceans of the mid-latitudes. As AOTD represents our first version of the Arctic observation dataset, we referred to the standardized procedures outlined in the WOD technical manual and relevant literature during the quality control process. Taking into full account the unique characteristics of the Arctic Ocean and the scarcity of data, we adopted relatively mature quality control methods to ensure the reliability of the observational data.

The quality control process for the dataset in this paper draws on existing automatic quality control processes25, e.g., automated detection30,31, as well as methods from the WOD technical manual32 for quality control. Each profile’s physical variables are subjected to automatic inspection and marking, encompassing standardization preprocessing, quality control, interpolation to standard layers, and secondary quality control after interpolation. The quality control process of this paper is shown in Fig. 1.

Next, the study randomly selected profiles that passed and failed the quality control (Fig. 3) for comparison to demonstrate that after quality control, the quality and consistency of the observation dataset were significantly improved. That is, quality control retained the inherent characteristics of the data while eliminating profiles with errors that could be corrected due to uncontrollable reasons.

Randomly selected temperature-salinity profiles. In (a–e), the red curves represent profiles that passed quality control, while the blue curves represent profiles that did not. (a) and (b) show the temperature threshold quality control and temperature gradient quality control, respectively. (c) and (d) show the salinity threshold quality control and salinity gradient quality control, respectively. (e) shows the density gradient quality control. (f) shows the 3-sigma test, where the grey curves represent temperature profiles at randomly selected grid points, the yellow curve is the mean, and the blue and red curves represent the minimum and maximum temperature values, respectively.

First, the original observation dataset collected is subjected to standardized preprocessing, during which abnormal files—with garbled values in key oceanographic variables such as longitude, latitude, temperature, and salinity—are excluded. Next, based on temperature and salinity profile data, ocean elements such as depth, pressure and density are calculated.

Quality control is then conducted on the data that have been standardized, mainly including position and time test, deep reversal and repeatability test, T/S extreme test, T/S gradient test, and density gradient test. Through preprocessing and quality control, AOTD is ultimately obtained, and is shown to be consistent with the actual ocean temperature and salinity structure of the Arctic region. Unless otherwise specified, the salinity referred to in this article is Practical Salinity.

-

(1)

Position and time test

The position of each observation profile must meet the requirements: latitude of 60°N–90°N, and longitude of 180°W–180°E. In addition, we also performed a topographic check using ETOPO5 data. The positions are compared with the global land positions, and if the buoy position is not at sea, it is considered an error. The date and time of each profile must also meet the requirements: year between 1983 and 2023, month between January and December, day within the valid range for that month, hour between 0:00 and 23:00, and minute between 0:00 and 0:59.

-

(2)

Deep reversal and repeatability test

The following observation points are excluded: those where a depth reading is shallower than the previous one (reversal), and where a reading has the same depth as its preceding reading (repetition).

-

(3)

T/S extreme test

Based on the extreme values of temperature in the Arctic Ocean, which are −3 and 20 °C, and maximum and minimum salinity values of 40 and 0 PSU due to the presence of sea ice, range checks are used to filter out extreme values in the data. The temperature and salinity ranges vary with depth. The specific temperature and salinity thresholds are provided in the Table 2.

Table 2 T/S extreme test Standards. -

(4)

T/S gradient test

According to the sign of the gradient value, two types of gradients are tested. The relevant standards can be found in Table 3:

Table 3 Gradient Test Standards. Excessive Gradients: the gradient values decrease excessively in the depth direction. Any values exceeding the “Maximum Gradient Value” (MGV) are marked as gradient anomalies and excluded.

Excessive Inversions: the gradient values increase excessively in the depth direction. Data exceeding the “Maximum Inversion Value” (MIV) are marked as inversion anomalies and excluded.

-

(5)

Density gradient test

Density under different pressures must meet certain limiting conditions. When the pressure is between 0 and 30 dbar, the density gradient should be greater than −0.03; between 30 and 400 dbar, it should be greater than −0.02; and when the pressure exceeds 400 dbar, the density gradient should be greater than −0.01.

After the orderly quality control process has been completed, the dataset is then interpolated to standard layers. Original observation depths from different sources vary due to the different designs of observation instruments. Therefore, to unify the observation depths for ease of subsequent use, the quality-controlled observation profiles are interpolated along the depth to standard layers.

The standard layers are defined as the WOA annual mean climatology standard layers, with the deepest layer reaching 5,500 m, and there are 102 layers in total. To make the profiles interpolated to the standard layers more in line with the original observed profile curve, we selected a new interpolation method developed by Barker and McDougall in 202033. This method is specifically designed to preserve the physical properties of oceanographic profiles more effectively than traditional interpolation techniques.

Considering the impact of mathematical interpolation methods on the original data, a secondary temperature and salinity test is conducted on the interpolated data, including a T/S range test and T/S gradient test, to ensure the accuracy of the data as best as possible. To further eliminate singular values in the observation data, all observation profiles are screened using the 3σ test. The T/S range test is the 6th step of quality control, the T/S gradient test is the 7th step, and the 3σ test is the 8th step.

Objective analysis method

This paper constructs AOTD climatology by referring to the calculation method of BOA-Argo34. First, the observation dataset is categorized on a monthly basis. Then, a background field with a resolution of 0.25° × 0.25° is generated by gridding all temperature and salinity data on each vertical standard layer using the Cressman objective analysis method35 (Eqs. 1, 2). Based on this, the background field is then corrected using the Barnes successive correction method36,37 (Eqs. 1, 3), to obtain a monthly climatology product for the Arctic Ocean with a horizontal resolution of 0.25° × 0.25° and 57 vertical layers. We used different influence radii (R) for iterative correction in order to minimize the errors caused by the isotropic radius as much as possible. The production process is illustrated in Figs. 9–12.

Where \({f}_{i}^{n}\) is the analysis field at point \(i\) after \(n\) iterations; \({f}_{b}^{o}\) is the \({b}^{{th}}\) observation value within the search radius \({r}_{n}\) after the \({n}^{{th}}\) iteration; \({f}_{b}^{n}\) is the estimated value at position b after the \({n}^{{th}}\) iteration; \({r}_{n}\) is the influence radius of the observation point after the \({n}^{{th}}\) iteration; \({K}_{i}^{n}\) is the number of observations searched in the \({n}^{{th}}\) iteration; and \({\omega }_{{ib}}^{n}\) is the weight coefficient, calculated by Eq. (2). After multiple experiments, the \(R\) values we used are 321 km, 267 km, and 214 km.

The Barnes successive correction method is similar to the Cressman method, the main difference being that the weight coefficients of the Barnes method are calculated using Eq. (3). Where \(\alpha \) is the filtration constant, and \(\gamma \) is the convergence factor.

In this paper, the Cressman background field is constructed through three iterations, while Barnes correction is performed in two iterations, where \(\gamma \) is set to 0.2 and \(\alpha \) is set to 8 × 104 and 1.6 × 104 km2.

It should be noted that, due to the irregular distribution of AOTD in horizontal space, there is relatively sparse data or even none in areas such as the East Siberian and Kara Seas, and an abundance of data in areas like the Nordic Sea. This type of data clustering severely affects the results of objective analysis36,37,38. To address this issue, the method adopted here is to divide the Arctic Ocean (60°N-90°N) into grids of 0.25 × 0.25°, and within each grid, average multiple data points to make the spatial distribution of the observation profiles more uniform.

Furthermore, the seasonal variability in the current AOTD climatology is relatively weak, primarily due to limitations in both observational coverage and the objective analysis approach. To better capture seasonal changes in future versions of AOTD, we plan to implement seasonal fitting techniques, such as harmonic analysis, in regions with sufficient temporal coverage.

The method of calculating ocean heat content

Ocean Heat Content (OHC) is a crucial metric for quantifying Earth’s Energy Imbalance (EEI)39,40,41. 90% of the energy difference is stored in the ocean, which is the fundamental driver of global warming and the primary cause of the rapid decline in Arctic sea ice39,42. In addition to relying on direct observations to analyze EEI, the Earth’s energy budget can also be assessed from the perspective of energy storage43,44.

In the Arctic, the presence of sea ice limits the utility of temperature at specific depths as a proxy for regional warming. Instead, OHC, which reflects the integrated internal heat content of the entire water column, provides a more stable and physically meaningful indicator45. Moreover, accurate estimates of OHC can serve as an independent validation of the robustness and reliability of the AOTD climatology. We use formula 4 to calculate ocean heat content. In addition, we also calculated the heat content of the entire pan-Arctic sea area.

Where \({\rho }_{0}\) is the density of seawater; \({C}_{p}\) is the specific heat capacity of seawater; \(T\left(t,x,y,z\right)\) is the seawater temperature; and \({z}_{1}\) is the bottom of the integral, which is 700 m in this article and \({z}_{2}\) is the sea surface level.

The method of Interpolation

Isopycnal and isobaric interpolation are common interpolation methods in the field of atmospheric and oceanic sciences46. Isopycnal interpolation is more precise and has a clearer physical meaning, especially in studying phenomena such as thermal structures, density driven flows, and gravity waves46,47,48,49. Isobaric interpolation is widely used in some ocean products such as WOA, EN450, and other datasets51.

Given the relatively sparse observations over the shelf seas and the central Arctic Ocean, we performed objective analysis on isobaric surfaces to minimize interpolation uncertainty.

Data Records

The Arctic Ocean Thermohaline Dataset (AOTD) is divided into two parts: a gridded climatology dataset and a scatter observation dataset, both of which are available on figshare.

Grid: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27645738.v152,

Scatter: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28825490.v153.

The scatter dataset contains a total of 414221 quality-controlled in situ observations, which have been interpolated onto standard depth levels. These data represent the final, cleaned results after rigorous quality control procedures.

The climatology dataset consists of 12 NetCDF files, each representing a monthly average from January to December. It includes temperature and salinity climatological fields spanning the period 1983–2023, covering the Arctic Ocean from 60°N to 90°N, with a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°.

Technical Validation

AOTD

After the aforementioned steps of data quality control, we finally obtained a total of 414221 temperature and salinity profiles(Fig. 4a). Observations from these two data sources are primarily concentrated in regions such as the Nordic Sea, Fram Strait, Barents Sea and Beaufort Sea, while they are relatively sparse in areas like the Bering Strait and East Siberian Sea. The observation positions of Argo, ITP, Xuelong and Xuelong-2 Research Expedition, Bol and Nabos in the Arctic are shown in Fig. 4d. The data from the Xuelong and Xuelong-2 Research Expedition have to some extent compensated for the lack of observation in the Chukchi Sea and East Siberian Sea, and further enriched the observation in the central Arctic region.

To evaluate the overall spatial distribution characteristics of the collected data, we calculated the average number of observations within each equal-area grid cell and conducted a density visualization analysis for each region. The results further illustrate the spatial density of the observations (Fig. 5). In general, data density decreases with increasing latitude. The highest observation densities are found in the Nordic Seas, Fram Strait, and Beaufort Sea, while the lowest densities are observed in the East Siberian Sea, Kara Sea, and Laptev Sea.

From the time distribution 12of the data, it is clear that Arctic observations before 2003 were relatively scarce (Fig. 6a,b). After 2005, the data volume steadily increased, peaking in 2019. After 2012, Arctic observations represented by the Xuelong and Xuelong-2 Research Expedition increased significantly, supplementing the WOD and CMEMS datasets. The distribution of temperature–salinity profiles at different depths is shown in Fig. 6c, indicating that the observation density is highest at depths deeper than 200 m, then begins to decrease by an order of magnitude at depths around 700 m, and drops sharply at depths greater than 1,500 m.

To validate the quality and accuracy of AOTD, an analysis and validation was conducted from three aspects: the horizontal spatial distribution characteristics of the dataset, the water mass structure in typical regions, and the comparison of individual profiles.

First, temperature–salinity scatter plots were created for data at three different depths in the horizontal direction (Fig. 7), and an analysis was conducted on the physical processes reflected by the horizontal distribution of the data. AOTD effectively reflects the temperature–salinity structure of the Arctic Ocean.

Near the surface, high-temperature and high-salinity Atlantic Water flows into the Barents Sea and Arctic Ocean on the Atlantic side54,55,56, while cold and low-salinity polar water flows out of the Arctic Ocean into the Nordic Sea along with the East Greenland cold current56, and Pacific Water can also be captured on the Bering Strait side57,58. Near the 300 m layer, influenced by Atlantic Water, the Norwegian Sea and Eurasian Basin generally have higher temperatures and salinities compared to the Greenland Sea and Canada Basin59, while the Beaufort Sea has relatively low temperature and salinity60. At the 1,200 m layer, observations in the central Arctic are sparse, and the temperature–salinity tends to be stable. However, in Baffin Bay and the North Atlantic south of Greenland, the water masses still have high temperature and salinity61. In general, AOTD can comprehensively reflect the true temperature and salinity distribution characteristics of the Arctic Ocean.

In addition, typical water mass structures from the five regions shown in Fig. 2 were selected for analysis (Fig. 8). The results indicate that on the side of the Fram Strait, Area1 (near the coast of Norway) shows the presence of high-temperature and high-salinity North Atlantic Water54,56,62 (Atlantic Water, AW), while Area2 (east of Greenland) also responds well to low-temperature and low-salinity water masses flowing out of the Arctic Ocean along the East Greenland Cold Current. In Area2 (along the bank of the Bering Strait), there is a significant seasonal variation in the water masses57,58, and AOTD effectively reflects the temperature changes of the summer Bering Strait Water (sBSW) and winter Bering Strait Water (wBSW). Regions 4 and 5 represent the water masses of the Beaufort Sea and the Eurasian Basin, respectively. Compared to Region 5, the upper-layer salinity in Region 4 is lower, which clearly reflects the freshwater characteristics of the Beaufort Sea and highlights the differences between the Eurasian Basin and the Canadian Basin.

AOTD climatology

Climatology products can intuitively display the average values, distribution and trends of climate elements within specific areas and time periods. Climatology products established based on in situ observation datasets more accurately reflect the characteristics of phenomena over a certain time scale, and serve as reference standards.

Subsequently, to evaluate the quality of AOTD climatology, we selected March and September as typical months representing the winter and summer of the Arctic Ocean, and compared them with the monthly WOA18 data with a resolution of 0.25 × 0.25°.

Figure 9 shows a comparison of the temperature variables of WOA18 and AOTD climatology for March, when the overall temperature climatology showed a warmer Atlantic side, decreasing with increasing depth. Near the surface, the Nordic Sea has higher temperatures, generally above 1 °C, and closer to the Atlantic the temperature rises, peaking at over 8 °C. At 300 m, the seawater temperature in the central area of the Arctic Ocean rises, while that in the Nordic Sea drops. At 1,000 m, except for relatively high temperature seawater on the North Atlantic side, the climatological temperature remains stable at around 0 °C.

The main differences between the AOTD climatology temperature variables and the WOA18 temperature variables in March are primarily observed in the near-surface layer where the Arctic Ocean exchanges water with the outside. In the Fram Strait, Barents Sea and Bering Sea, the temperature differences may exceed 2 °C. Besides the fact that the observations are mostly distributed during the sea ice melting period, leading to a higher climatological temperature, the diversity of ocean currents and complexity of the terrain in the aforementioned sea areas also play a role. The objective analysis method used for creating the climatology assumes that ocean currents are isotropic in nature, without considering the spatial discontinuity of the currents under special topographical conditions. This leads to the phenomenon of selecting spatially discontinuous water masses across islands63.

Figure 10 shows a comparison of the temperature variables of WOA18 and AOTD climatology for September. The results indicate that the near surface temperature climatology in September is consistent with that in March, with the Atlantic side being warmer. However, a larger area of the Nordic Sea has temperatures exceeding 8 °C, reflecting the seasonal variation of seawater temperature in the Arctic Ocean. The deep-layer temperatures in September do not differ greatly from those in March, since the deep layers are less affected by atmospheric heat exchange and sea ice melting.

The main differences between the AOTD climatology and WOA18 temperature variables in September are observed in the Nordic, Barents and Beaufort Seas, with most differences being around 1 °C. The climatology presented in this paper is more continuous in the Nordic Sea, which may be due to the greater number of observations used.

Figure 11 presents a comparison of the salinity variables of WOA18 and AOTD climatology for March. Contrary to the temperature differences, the salinity differences are more pronounced in the central near-surface layer of the Arctic Ocean. As shown in Fig. 5, intuitively speaking, the magnitude of salinity differences is positively correlated with data density. The reason for this lies in that sea ice has a greater impact on salinity. In the deep layers, there is no significant difference in the salinity variables between AOTD climatology and WOA18.

Figure 12 displays the salinity variables of WOA18 and AOTD climatology at the 50, 300 and 1,000 m depths for September, and the differences between the two. The salinity deviations in the upper layer are significant near the coast and in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, reaching up to 1psu. In addition, there is a considerable salinity deviation in the central Arctic region, which may be due to the use of more observations in this area for the climatology presented in this paper.

In general, temperature differences are primarily found at water exchange locations and greatly influenced by ocean currents; salinity differences are mainly observed in the central Arctic Ocean, and are significantly affected by sea ice. The temperature and salinity differences between AOTD climatology and WOA18 in September are much smaller than those in March. This is because, in addition to ocean currents, the interaction among sea ice, seawater and the atmosphere also has a certain impact on temperature during the winter. In the summer, as the sea ice melts, the properties of the seawater stabilize, and the increased number of observations make the climatology results more stable.

The temperature section of the two climate states in March show a clear layered structure, with temperatures above 300 m around −1 °C (Fig. 13). The temperature on one side of the Eurasian Basin is influenced by the North Atlantic Warm Current at 200–700 m, forming a thermocline. Temperatures deeper than 800 m gradually decrease with temperature; The salinity section shows that the salinity is lower at 50 m on one side of the Canadian Basin, but from 50 m to 400 m, the salinity gradually increases with depth. This high salinity phenomenon gradually weakens from the Beaufort Sea to the Barents Sea. Compared with WOA, the AOTD climatology thermohaline section in March has stronger continuity and more stable structure.

The comparison results of climate profiles in September are shown in Fig. 14. The overall pattern and structure are similar to those in March, indicating the stability of AOTD climatology.

To further demonstrate the positive feedback effect of observation density on the climatology dataset, we selected the 168°W section in September for analysis. This area has been a key focus of Xuelong and Xuelong-2 Research Expedition over the years. Some incremental observations have been accumulated and collected in the dataset. The analysis results in Fig. 15 show that this section can reflect the rather high-temperature Pacific Water flowing into the Arctic Ocean, with a clear meridional temperature stratification, and a trend of temperature gradually decreasing from south to north. In this section, both temperature and salinity undergo vertical changes, with the temperature decreasing and salinity increasing as the depth increases.

Comparing WOA18 and AOTD climatology, at 67°N–70°N, the climatology presented in this paper has higher temperatures in the upper layer (20 m), reaching up to 8 °C, while the value of WOA18 is only around 6 °C (Fig. 15). In the high-latitude region (70°N–75°N), the two kinds of climatology differ little, both being around 1 °C. The difference in salinity between the two is evident at 69°N–73°N, where AOTD climatology has a higher salinity than WOA18 in the upper layer (above 20 m), by 1psu. The reasons for the differences, aside from the differences in the methods used to construct the climatology, include the fact that AOTD has more observations in this area (Fig. 4d), which has a certain impact on the climatology results.

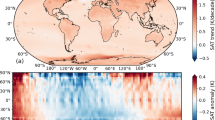

Based on the climatology dataset constructed in this paper, we calculated the heat content in the Arctic Ocean above a depth of 700 m using Eq. (4) based on AOTD climatology and compared it with the heat content calculated based on WOA18; the results are shown in Fig. 16.

The horizontal distribution in both cases has a gradual decrease from the Nordic Sea to central Arctic Ocean, with positive values in the Eurasian Basin and negative ones in the Canada Basin64. As the Atlantic Water flows further into the Arctic, its temperature gradually decreases, and so does the heat content. In September, the OHC in the Eurasian Basin is much higher than in March.

The differences in OHC are primarily observed at the Fram Strait in March, which serves as the entry point for Atlantic Water into the Arctic Ocean. AOTD climatology shows a higher OHC in this area. In other regions and during September, the OHC of AOTD climatology does not differ greatly from that of WOA18.

However, it should be noted that the heat content in the central Arctic is inherently at a relatively low level. Yet, Fig. 16c,f show that the OHC in the central Arctic exhibits variations of a similar magnitude to those in the Nordic Seas. This implies that the central Arctic OHC has a much larger percentage difference. This phenomenon indicates that the central Arctic is warming faster compared to other regions, which may, to some extent, reduce sea ice thickness, concentration, and extent.

In view of the large differences in total OHC between the Nordic Seas and the Arctic Ocean basins and shelf seas shown in Fig. 16, we decided to analyze the seasonal cycle of total ocean heat content (The results calculated using Eq. (4) were multiplied by the grid-cell area and then summed) and its anomaly separately for the Arctic Ocean basins and shelf seas (Fig. 17a) and the Nordic Seas (Fig. 17b).

Figure 17 shows that both regions exhibit similar seasonal variation patterns. However, the value of the AOTD climatology is larger than that of WOA18, as shown in Figs. 9, 10. This may be due to differences in data sources and periods, as well as the selection of only thermohaline profiles.

Past research on OHC has often involved analyzing the spatiotemporal variations65,66,67 in OHC to explore the causes and mechanisms of changes, which requires high reliability and accuracy of the data used. The difference between AOTD climatology and WOA18 partly reflects the increase in heat content in the upper 700 m across the pan-Arctic region due to climate change. The most direct consequence of this change is the thinning of Arctic sea ice and the continuous reduction of sea ice extent, which highlights the importance of monitoring heat content variations. However, observations in the Arctic Ocean are sparse, making it difficult to produce higher time-resolution datasets (yearly or even monthly) using purely in situ data. Such datasets are crucial for studying changes in heat content, and thus, it is necessary to increase efforts in the Arctic, particularly in collecting and quality-controlling in situ data in the central Arctic.

Data availability

All data links and access information related to this study are provided below. The AOTD dataset has been published on Figshare and is publicly accessible. The climatology version of the AOTD can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27645738.v152, the scatter data of AOTD can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28825490.v113,53 dataset is publicly available at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/world-oceanatlas. The WOD1812 dataset is publicly available at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/world-ocean-database. The Argo14 dataset is publicly available at https://argo.ucsd.edu. The ITP15 dataset is publicly available at https://www2.whoi.edu/site/itp. The CMEMS11 dataset is publicly available at https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product. The NABOS68 dataset is publicly available at https://uaf-iarc.org/nabos-products. The BOL69 dataset is publicly available at https://bolin.su.se/data. The dataset from Xuelong and Xuelong-217 is publicly available at https://datacenter.chinare.org.cn/data-center/dindex.

Code availability

The reproduction code of this article is available at: https://github.com/niuda-niuer/An-Arctic-Ocean-Thermohaline-Dataset.

Change history

26 January 2026

In this article the affiliations were in the incorrect order. The original article has been corrected.

References

Pidwirny, M. Fundamentals of physical geography. Okonagan: Univ. of British Columbia. http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/contents.htm (2004).

Gordon, A. L. & Baker, F. W. G. Oceanography: Annals of The International Geophysical Year, Vol. 46. https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=2rc4BQAAQBAJ (Pergamon, 2013).

Timmermans, M. & Marshall, J. Understanding Arctic Ocean Circulation: A Review of Ocean Dynamics in a Changing Climate. JGR Oceans 125, e2018JC014378, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JC014378 (2020).

Markus, T., Stroeve, J. C. & Miller, J. Recent changes in Arctic sea ice melt onset, freezeup, and melt season length. J. Geophys. Res. 114, 2009JC005436, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JC005436 (2009).

Stroeve, J. & Notz, D. Changing state of Arctic sea ice across all seasons. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 103001, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aade56 (2018).

Overland, J. E., Wood, K. R. & Wang, M. Warm Arctic—cold continents: climate impacts of the newly open Arctic Sea. Polar Research 30, 15787, https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v30i0.15787 (2011).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. The central role of diminishing sea ice in recent Arctic temperature amplification. Nature 464, 1334–1337, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09051 (2010).

Dai, A., Luo, D., Song, M. & Liu, J. Arctic amplification is caused by sea-ice loss under increasing CO2. Nat Commun 10, 121, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07954-9 (2019).

Box, J. E. et al. Key indicators of Arctic climate change: 1971–2017. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 045010, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aafc1b (2019).

Davis, P. E. D., Lique, C. & Johnson, H. L. On the Link between Arctic Sea Ice Decline and the Freshwater Content of the Beaufort Gyre: Insights from a Simple Process Model. Journal of Climate 27, 8170–8184, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00090.1 (2014).

Arctic Ocean- In Situ Near Real Time Observations. E.U. Copernicus Marine Service Information (CMEMS). Marine Data Store (MDS) https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00031.

Boyer, T. P., Baranova, O. K. & Coleman, C. World Ocean Database. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/world-ocean-database (2018).

World Ocean Atlas: Product Documentation. A. Mishonov, Technical Editor. https://doi.org/10.25923/tzyw-rp36 (2018).

Wong, A. P. S. et al. Argo Data 1999–2019: Two Million Temperature-Salinity Profiles and Subsurface Velocity Observations From a Global Array of Profiling Floats. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 700, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00700 (2020).

Toole, J. M. et al. Ice-Tethered Profiler observations: Vertical profiles of temperature, salinity, oxygen, and ocean velocity from an Ice-Tethered Profiler buoy system. https://doi.org/10.7289/v5mw2f7x (2016).

Mauritzen, C. et al. Closing the loop – Approaches to monitoring the state of the Arctic Mediterranean during the International Polar Year 2007–2008. Progress in Oceanography 90, 62–89, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2011.02.010 (2011).

Xuelong & Xuelong-2. https://datacenter.chinare.org.cn/data-center/dindex.

Zika, J. D. et al. Improved estimates of water cycle change from ocean salinity: the key role of ocean warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 074036, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aace42 (2018).

Zou, L., Zhou, T., Tang, J. & Liu, H. Introduction to the Regional Coupled Model WRF4-LICOM: Performance and Model Intercomparison over the Western North Pacific. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 37, 800–816, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-020-9268-6 (2020).

Behrendt, A., Sumata, H., Rabe, B. & Schauer, U. UDASH – Unified Database for Arctic and Subarctic Hydrography. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-10-1119-2018 (2018).

Steele, M., Morley, R. & Ermold, W. PHC: A Global Ocean Hydrography with a High-Quality Arctic Ocean. J. Climate 14, 2079–2087 10.1175/1520-0442(2001)014<2079:PAGOHW>2.0.CO;2 (2001).

Environmental Working Group. Environmental Working Group Arctic Meteorology and Climate Atlas. (G01938, Version 1). Fetterer, F. & Radionov, V. F. (Eds.). Boulder, Colorado USA. National Snow and Ice Data Center. https://doi.org/10.7265/N5MS3QNJ (2000).

Zuo, H., Balmaseda, M. A., Tietsche, S., Mogensen, K. & Mayer, M. The ECMWF operational ensemble reanalysis–analysis system for ocean and sea ice: a description of the system and assessment. Ocean Sci. 15, 779–808, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-15-779-2019 (2019).

Nguyen, A. T. et al. The Arctic Subpolar Gyre sTate Estimate: Description and Assessment of a Data‐Constrained, Dynamically Consistent Ocean‐Sea Ice Estimate for 2002–2017. J Adv Model Earth Syst 13, e2020MS002398, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020MS002398 (2021).

Good, S. et al. Benchmarking of automatic quality control checks for ocean temperature profiles and recommendations for optimal sets. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 1075510, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.1075510 (2023).

Goni, G. J. et al. More Than 50 Years of Successful Continuous Temperature Section Measurements by the Global Expendable Bathythermograph Network, Its Integrability, Societal Benefits, and Future. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 452, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00452 (2019).

Tan, Z., Zhang, B., Wu, X., Dong, M. & Cheng, L. Quality control for ocean observations: From present to future. Sci. China Earth Sci. 65, 215–233, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-021-9846-7 (2022).

Roemmich, D. et al. On the Future of Argo: A Global, Full-Depth, Multi-Disciplinary Array. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 439, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00439 (2019).

Smith, D., Timms, G., De Souza, P. & D’Este, C. A Bayesian Framework for the Automated Online Assessment of Sensor Data Quality. Sensors 12, 9476–9501, https://doi.org/10.3390/s120709476 (2012).

Thadathil, P., Ghosh, A. K., Sarupria, J. & Gopalakrishna, V. An interactive graphical system for XBT data quality control and visualization. Computers & geosciences 27, 867–876, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0098-3004(00)00172-2 (2001).

Gouretski, V. & Cheng, L. Correction for Systematic Errors in the Global Dataset of Temperature Profiles from Mechanical Bathythermographs. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 37, 841–855, https://doi.org/10.1175/JTECH-D-19-0205.1 (2020).

Garcia, H.E., et al World Ocean Database 2023: User’s Manual. Mishonov, A. V. Technical Ed., NOAA Atlas NESDIS 98, pp 129, https://doi.org/10.25923/j8gq-ee82 (2024).

Barker, P. M. & McDougall, T. J. Two Interpolation Methods Using Multiply-Rotated Piecewise Cubic Hermite Interpolating Polynomials. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 37, 605–619, https://doi.org/10.1175/JTECH-D-19-0211.1 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Development of a global gridded Argo data set with Barnes successive corrections: A NEW GLOBAL GRIDDED ARGO DATA SET. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 122, 866–889, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JC012285 (2017).

Cressman, G. P. An Operational Objective Analysis System. Mon. Wea. Rev. 87, 367–374., https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(1959)087<0367:AOOAS>2.0.CO;2 (1959).

Barnes, S. L. A technique for maximizing details in numerical weather map analysis. Journal of Applied Meteorology (1962-1982) 396–409 10.1175/1520-0450(1964)003<0396:atfmdi>2.0.co;2 (1964).

Barnes, S. L. Mesoscale objective analysis using weighted time series observations, NOAA Tech. Memo ERL NSSL-62, 41 pp., Natl. Severe Storms Lab., Norman, Okla (1973).

Smith, D. R., Pumphry, M. E. & Snow, J. T. A comparison of errors in objectively analyzed fields for uniform and nonuniform station distributions. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 3, 84–97. 10.1175/1520-0426(1986)003<0084:ACOEIO>2.0.CO;2 (1986)

Hansen, J. et al. Earth’s energy imbalance: Confirmation and implications. science 308, 1431–1435, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1110252 (2005).

Trenberth, K. E., Fasullo, J. T. & Balmaseda, M. A. Earth’s Energy Imbalance. Journal of Climate 27, 3129–3144, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00294.1 (2014).

Hansen, J., Sato, M., Kharecha, P. & Von Schuckmann, K. Earth’s energy imbalance and implications. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 13421–13449, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-13421-2011 (2011).

Abraham, J. P. et al. A review of global ocean temperature observations: Implications for ocean heat content estimates and climate change. Reviews of Geophysics 51, 450–483, https://doi.org/10.1002/rog.20022 (2013).

Levitus, S. et al. World ocean heat content and thermosteric sea level change (0–2000 m), 1955–2010. Geophysical Research Letters 39, 2012GL051106, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL051106 (2012).

Loeb, N. G. et al. Observational Assessment of Changes in Earth’s Energy Imbalance Since 2000. Surv Geophys 45, 1757–1783, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-024-09838-8 (2024).

Cheng, L. et al. Ocean heat content in 2023. Nat Rev Earth Environ 5, 232–234, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-024-00539-9 (2024).

Gomis, D., Pedder, M. A. & Viúdez, A. Recovering spatial features in the ocean: performance of isopycnal vs. isobaric analysis. Journal of Marine Systems 13, 205–224, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-7963(96)00116-9 (1997).

Schmidtko, S., Johnson, G. C. & Lyman, J. M. MIMOC: A global monthly isopycnal upper‐ocean climatology with mixed layers. JGR Oceans 118, 1658–1672, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrc.20122 (2013).

Kulan, N. & Myers, P. G. Comparing two climatologies of the Labrador Sea: Geopotential and isopycnal. Atmosphere-Ocean 47, 19–39, https://doi.org/10.3137/OC281.2009 (2009).

Gouretski, V. World Ocean Circulation Experiment – Argo Global Hydrographic Climatology. Ocean Sci. 14, 1127–1146, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-14-1127-2018 (2018).

Good, S. A., Martin, M. J. & Rayner, N. A. EN4: Quality controlled ocean temperature and salinity profiles and monthly objective analyses with uncertainty estimates. JGR Oceans 118, 6704–6716, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JC009067 (2013).

Cheng, L. et al. IAPv4 ocean temperature and ocean heat content gridded dataset. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 3517–3546, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-3517-2024 (2024).

Li, J. An Arctic Ocean Thermohaline Dataset. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27645738.v1 (2024).

Li, J. AOTD_scatter. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28825490.v1 (2025).

Schauer, U., Loeng, H., Rudels, B., Ozhigin, V. K. & Dieck, W. Atlantic Water flow through the Barents and Kara Seas. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 49, 2281–2298, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0637(02)00125-5 (2002).

Rabe, B. et al. Arctic Ocean basin liquid freshwater storage trend 1992–2012. Geophysical Research Letters 41, 961–968, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013GL058121 (2014).

Seidov, D. et al. Oceanography north of 60°N from World Ocean Database. Progress in Oceanography 132, 153–173, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2014.02.003 (2015).

Steele, M. et al. Circulation of summer Pacific halocline water in the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 109, 2003JC002009, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JC002009 (2004).

Coachman, L. K. & Barnes, C. A. The Contribution of Bering Sea Water to the Arctic Ocean. ARCTIC 14, 146–161, https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic3670 (1961).

Aagaard, K., Swift, J. H. & Carmack, E. C. Thermohaline circulation in the Arctic Mediterranean Seas. J. Geophys. Res. 90, 4833–4846, https://doi.org/10.1029/JC090iC03p04833 (1985).

Proshutinsky, A., Bourke, R. H. & McLaughlin, F. A. The role of the Beaufort Gyre in Arctic climate variability: Seasonal to decadal climate scales. Geophysical Research Letters 29, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL015847 (2002).

Tang, C. C. L. et al. The circulation, water masses and sea-ice of Baffin Bay. Progress in Oceanography 63, 183–228, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2004.09.005 (2004).

Rasmussen, T. L. et al. Spatial and temporal distribution of Holocene temperature maxima in the northern Nordic seas: interplay of Atlantic-, Arctic- and polar water masses. Quaternary Science Reviews 92, 280–291, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.10.034 (2014).

Lyman, J. M. & Johnson, G. C. Estimating Global Ocean Heat Content Changes in the Upper 1800 m since 1950 and the Influence of Climatology Choice*. Journal of Climate 27, 1945–1957, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00752.1 (2014).

Serreze, M. C. et al. The large‐scale energy budget of the Arctic. J. Geophys. Res. 112, 2006JD008230, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD008230 (2007).

Chepurin, G. A. & Carton, J. A. Subarctic and Arctic sea surface temperature and its relation to ocean heat content 1982–2010. J. Geophys. Res. 117, 2011JC007770, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JC007770 (2012).

Tsubouchi, T. et al. Increased ocean heat transport into the Nordic Seas and Arctic Ocean over the period 1993–2016. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 21–26, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00941-3 (2021).

Cheng, L. et al. Improved estimates of ocean heat content from 1960 to 2015. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601545, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1601545 (2017).

Pnyushkov, A. V. & Polyakov, I. V. Nansen and Amundsen Basins Observational System (NABOS). https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2022.104.

Leck, C. et al. Data from expedition Arctic Ocean, 2018. Dataset version 4. Bolin Centre Database. https://bolin.su.se/data/oden-ao-2018-expedition-1 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National key research and development program (2023YFC3107804). Specifically, this study received assistance from the Polar Research Institute of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiangyu Wu and Xidong Wang conceived the research. JinLong Li, Xiangyu Wu and Xidong Wang were involved in data collection and analysis. JinLong Li and Xiangyu Wu wrote the manuscript. All authors read, revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Wu, X. & Wang, X. An Arctic Ocean Thermohaline Dataset. Sci Data 12, 1607 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05855-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05855-3