Abstract

This study provides a comprehensive outdoor ultra-wideband (UWB) dataset to examine the multipath effects in line-of-sight and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) environments for real-time localization. Specifically, the dataset comprises static and dynamic datasets designed to capture discrete multipaths affected by antenna height, obstructions, and time-varying environments. A static dataset varies the antenna height and distance to analyze the multipath interference on the received signal strength and ranging error with a UWB pair and walls to replicate NLOS environments. These measurements reveal ranging errors from ground reflections and Fresnel zone signal attenuations depending on the antenna height, which should be prevented in anchor deployment. The dynamic dataset includes IMU, GNSS, and UWB measurements collected using a unique mobile robot system under various anchor configurations. This dataset aims to facilitate the evaluation of localization methods against high-accuracy RTK-GNSS. Two representative methods, least-squares and an error-state Kalman filter, are provided to support localization improvements. These datasets have accelerated the study of real-time localization because these datasets are the novel datasets measured in various outdoor environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Ultra-wideband (UWB) technology has emerged as a key solution for high-precision and real-time localization in wireless communication. Specifically, the UWB transmits short pulses over a wide frequency spectrum and estimates the relative distance based on the time-of-flight. Therefore, UWB can measure precise ranging with minimal interference unlike conventional wireless communication methods including Bluetooth and Wi-Fi1. This high-precision distance measurement capability has rendered UWB a representative technology for real-time localization in diverse environments. For example, accurate localization with UWB prevents collisions between workers and autonomous robots in the industry2. The UWB-based precise monitoring of pedestrians in real time also significantly contributes to the development of urban autonomous driving systems to ensure pedestrian safety3.

The increase in the demand for UWB in various applications has motivated extensive research, which enhanced the performance of UWB across diverse environments4,5,6 because the performance of UWB sensors is affected by various environmental factors including static and dynamic scenarios and line-of-sight (LOS)/non-line-of-sight (NLOS) environments7,8. These studies have elucidated the influence of environmental factors on the quality of UWB measurements. Specifically, the measurement accuracy in dynamic scenarios is significantly lower than that in static scenarios because dynamic scenarios contain movement and time-varying multipath effects9. NLOS environments also extend the signal path due to obstructions, resulting in an overestimation of the actual distance10 and a reduction in UWB RSS11. These studies offered valuable insights that support a detailed analysis of UWB characteristics. Note that conventional studies have often focused only on a single environmental factor, which includes obstruction by walls or furniture, static or dynamic movement, or the contrast between indoor and outdoor environments. This singular focus limits the capability to understand the effects of multiple environmental factors on UWB signal quality. Multiple environmental factors influence signal quality in real-world scenarios. The lack of consideration for these factors can reduce the reliability and accuracy of UWB-based localization systems. Therefore, the consideration of multiple environmental factors is essential for ensuring robust and generalizable UWB system performance.

The optimal anchor placement of UWB is also important to maximize performances because an inferior placement can reduce the localization accuracy and, thereby, limit the communication coverage of UWB systems12,13. Several optimization methods have been proposed for anchor placement to enhance the performance of UWB. An improved artificial rabbits optimization algorithm was proposed to determine the optimal anchor positions to achieve a high positioning accuracy by minimizing the position dilution of precision (PDOP) and average positioning error14. This method enhances positioning accuracy by minimizing PDOP but has limitations in addressing signal coverage in UWB systems. Another study manually defined coverage areas to reduce deployment costs and addressed a genetic algorithm (GA) to optimize anchor placement by minimizing the PDOP15. This method reduced deployment costs within manually selected areas, but communication coverage is difficult to generalize in real-world environments. Note that UWB data transmission consistency is sensitive to variations in ground reflections and multipath effects, which are caused by differences in antenna height16,17,18 Therefore, conventional optimization methods that focus solely on the improvement of localization accuracy or rely on predefined coverage areas without consideration of antenna height have limitations in addressing both accurate positioning and reliable data transmission, which are essential for the practical deployment of UWB systems.

Conventional studies have actively examined indoor UWB datasets under diverse environmental factors including multipath effects and NLOS conditions, to enable benchmark UWB localization performance and anchor placement optimization. Specifically, the indoor dataset provides UWB ranging measurements and multimodal sensor data to support the analysis of localization errors and benchmark the UWB positioning performance for mobile robots19. Datasets including RSS, channel impulse response (CIR), and UWB ranging data also enable a detailed analysis of signal propagation characteristics and ranging error modeling in complex indoor environments to optimize anchor placement20,21. These datasets are effective for studying several localization methods optimized for indoor environments. These datasets are effective for studying several localization methods optimized for indoor environments. However, the datasets are limited to short-range measurements typically within 15 m and constrained to predefined indoor environments. Thus, current indoor datasets provide limited insights into the UWB performances in larger outdoor spaces.

Outdoor studies have also been conducted to characterize UWB measurement performances over long distances in various outdoor scenarios22. The outdoor UWB datasets have enabled anchor placement optimization and benchmarking of UWB localization performances. Specifically, a benchmark dataset provides UWB ranging data, inertial measurement unit (IMU) data, and ground truth from robotic stations across five diverse environments to evaluate UAV positioning performances and support ranging error modeling for anchor placement optimization23. Another dataset was constructed to provide UWB ranging measurements and ground-truth trajectories for multi-robot systems with various anchor placements and tag trajectories24. This dataset is aimed at enabling the performance evaluation of relative localization algorithms in diverse environments and orientation conditions. These datasets support the UWB localization analysis for robot systems in diverse outdoor environments. However, these outdoor datasets have limitations due to the lack of signal-related measurements such as RSS and CIR, which are essential for analyzing signal propagation characteristics. Therefore, outdoor datasets that include UWB signal strength information such as RSS and CIR are required to accurately analyze the signal propagation characteristics.

To overcome the limitations of current UWB datasets, this study constructed a new dataset to provide comprehensive outdoor measurements including UWB ranging data, RSS collected under static and dynamic scenarios, and LOS/NLOS environments. The dataset separates the conditions of the field experiments into LOS and NLOS scenarios to ensure a comprehensive evaluation of the UWB performance in diverse environments. The dataset also utilizes inexpensive UWB sensor modules configured for single-sided two-way ranging (SS-TWR) to enhance the economic feasibility25,26. Two distinct measurement configurations were developed: a static setup with a UWB transmitter–receiver pair, and a dynamic setup comprising four anchors and a mobile robot. The use of multiple systems as reference data allows for precise and efficient data collection, and ensures robustness by eliminating human-driven variability. The novelty and key contributions of this dataset are as follows.

-

A new dataset is constructed for outdoor environments by considering various influencing factors including static/dynamic and LOS/NLOS environments. The diversity of the dataset enables an in-depth analysis of UWB sensor performance and supports practical applications including NLOS classification and the development of robust localization algorithms under diverse real-world environments.

-

The dataset provides sufficient measurements for various anchor placements with different PDOP values and antenna heights. Therefore, this dataset can be used to study UWB measurement error models that consider both localization accuracy and signal strength for anchor placement optimization to maximize the UWB performance.

-

The dataset is constructed in outdoor environments to support the analysis of the UWB signal behavior under long-distance positioning scenarios. Measurements including RSS and CIR data are collected in distances of up to 60 m at various antenna heights. This feature indicates that this dataset enables the systematic analysis of signal propagation characteristics over long ranges.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Methods section presents the UWB hardware configuration and describes the data processing methodology. Data Records section outlines the dataset structure and content organization for the static and dynamic conditions. Technical Validation section provides comprehensive analyses of RSS variations, ranging errors, and localization accuracy comparisons between the least square (LS) and error state extended Kalman filter (ESKF) methods20,27. Finally, Usage Notes section discusses potential applications and future research directions using this dataset.

Methods

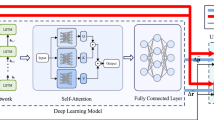

This section describes the measurement framework for examining the proposed dataset. Specifically, this section aims to enhance the understanding of the overall data construction pipeline. The framework comprises four primary phases: UWB prerequisites, hardware configuration, data processing, and field experiments (Fig. 1). The UWB prerequisite phase encompasses the ranging method and antenna delay calibration. These procedures are crucial for ensuring reliable data collection (Fig. 1(a)). An accurate calibration between the receiver and transmitter is essential for achieving high accuracy and robustness. The hardware configuration phase explains the sensor specifications, processors, and communication interfaces used in the dataset (Fig. 1(b)). Two experimental configurations are designed for both static and dynamic measurements. Third, the data processing phase addresses RSS estimation through CIR, coordinate alignment, and localization (Fig. 1(c)). RSS serves as a key indicator of UWB communication availability. Localization algorithms are essential for evaluating the proposed framework. Fourth, the field experiment phase presents the experimental setup for dataset measurement and outlines the measurement procedures (Fig. 1(d)). This phase aims to ensure the reliability of the dataset by systematically collecting and validating the data.

UWB prerequisites

This subsection presents two prerequisites for UWB data measurement: ranging method and antenna delay calibration. These methods are aimed at ensuring the reliability of the dataset. First, an optimal ranging method is selected to achieve high accuracy with low communication latency when constructing the dataset. Specifically, this study addressed a carrier frequency offset (CFO)-corrected single-sided two-way ranging (CC-SS-TWR) method to ensure accuracy and robustness by compensating for time-drift noises. Second, the antenna delay calibration aligns the measured time with the actual signal travel time to facilitate a more precise error analysis under multipath experimental conditions, ultimately improving the localization accuracy in real-world UWB applications. This calibration is essential for correcting hardware-induced time offsets, which vary among devices and can cause range inaccuracies.

First, CC-SS-TWR is addressed in the experiments because this method is effective for securing ranging accuracy and communication speed. Specifically, SS-TWR facilitates low-latency communication compared with double-sided TWR (DS-TWR) by minimizing the number of exchanged messages. However, conventional SS-TWR, which operates without clock synchronization between sensors, has limitations in terms of clock drift between the transmitter and receiver. CFO mismatches in the receiver/transmitter frequencies result in clock drift and, thereby, significant ranging errors. Note that the CC-SS-TWR integrates a single-sided TWR with CFO correction, indicating that the time-drift compensation method is incorporated into the SS-TWR. Figure 2 illustrates a conceptual diagram of SS-TWR, which includes a poll message sent from an anchor to a tag, followed by a response message from the tag back to the anchor. The mathematical representation of the time-of-flight \({T}_{{of}}\) is given by

where TB and TR denote the delay for a responder to send a reply and the round-trip time, respectively. Note that the two messages and simple equation (Eq. (1)) supports faster communication and straightforward Tof calculations in the SS-TWR. However, the absence of time synchronization between a tag and an anchor causes time drift between the sensor modules. This, in turn, causes ranging errors in the SS-TWR, suggesting that the CC-SS-TWR enhances the standard SS-TWR by applying a CFO correction to mitigate clock drift and maintain low-latency communication in real-time scenarios28. The time-of-flight Tof in the CC-SS-TWR is rearranged as follows:

where \({K}_{{offset}}\) denotes the CFO correction factor derived from the clock frequency discrepancies between the anchor and tag. Note that the CFO correction factor \({K}_{{offset}}\) is expressed as the ratio of the signal frequency received from the tag to the own internal reference frequency of anchor. The CFO correction factor \({K}_{{offset}}\) is computed as follows:

where \({f}_{c}\) is the ideal carrier frequency, \({k}_{A}\) and \({k}_{T}\) denote the clock error factors for the anchor and tag, and \({\epsilon }_{{AT}}\) is the additive offset, respectively. The additive offset \({\epsilon }_{{AT}}\) is estimated directly from the UWB sensor during the signal reception process. This value typically expressed in parts-per-million to allow for the precise calculation of the correction factor needed for accurate ranging. Therefore, the factor \({K}_{{offset}}\) scales \({T}_{B}\) to offset the CFO-induced drift and improve the ranging accuracy.

The second prerequisite for antenna delay calibration is crucial to ensure the accuracy of \({T}_{{of}}\). Antenna delays represent the internal time noise from the generation of transmission timestamps to the logging of reception timestamps, increasing the error with respect to the actual measurements. Therefore, the calibration process mitigates time variations by compensating for internal propagation delays. \({T}_{R}\) and \({T}_{B}\) are measured values that contain antenna delay noise from internal components such as manufacturing tolerances, circuit variations, and antennas. The actual value \({T}_{B,{actual}}\) considering antenna delays is computed as follows:

where \({t}_{i,{RX}}\), \({t}_{i,{TX}}\), and \({t}_{i,{AD}}\) denote the delay in receiving the poll message, delay in transmitting the response message, and antenna delay from the tag, respectively (Fig. 2). The actual value \({T}_{R,{actual}}\) is also computed as

where \({t}_{j,{RX}}\), \({t}_{j,{TX}}\), and \({t}_{j,{AD}}\) denote the delay in receiving the response message, delay in transmitting the poll message, and antenna delay from the anchor, respectively (Fig. 2). The actual values \({T}_{B,{actual}}\) and \({T}_{R,{actual}}\) should be computed to achieve a highly accurate ranging performance by eliminating these antenna delays from \({T}_{B}\) and \({T}_{R}\). Note that the antenna delays remain embedded in the measured signal propagation interval between the transmitted and received messages. Therefore, the final compensated \({T}_{{of}}\) is derived from Eq. (2), Eq. (4), and Eq. (5) as follows:

The antenna delays \({t}_{i,{AD}}\) and \({t}_{j,{AD}}\) cause the measured time to deviate from the actual \({T}_{{of}}\) in Eq. (6), leading to range offsets requiring correction. To mitigate the concern on the antenna delays \({t}_{i,{AD}}\) and \({t}_{j,{AD}}\), the calibration process was conducted for the dataset by executing an iterative procedure29,30,31. Specifically, two UWB devices were placed at the same height at a known horizontal distance of 2 m, and the antenna delay parameter was adjusted iteratively for each device based on 300 ranging measurements. This process continued until the mean of ranging measurements produced a ranging offset of less than 0.01 m from the 2 m ground-truth distance. The final calibrated antenna delay was then recorded in the transmit antenna delay register to ensure consistency in ranging accuracy.

Hardware configuration

The UWB measurement systems were designed to operate in two distinct environments to collect datasets under both static and dynamic conditions. The static environment provides a baseline measurement for evaluating sensor accuracy without external disruptions. Meanwhile, the dynamic environment captures the extent to which real-time motion impacts UWB signal reliability. The performance of UWB sensors depends on static and dynamic environments. A static environment minimizes variations in signal propagation and allows for the precise averaging of measurements with minimal multipath effects. In contrast, a dynamic environment increases variations in signal propagation due to anchor placement, target trajectory and increased multipath effects which reduce the accuracy of UWB measurements12. Therefore, specific hardware configurations for both static and dynamic conditions are necessary to establish precise measurements and analyze real-world applications.

A static measurement system was configured to examine the multipath influences, LOS/NLOS environments, and RSS. This configuration employs a single UWB receiver and transmitter (Fig. 1(b)) using Decawave’s MDEK1001 kit with a DWM1001-DEV board enclosed in plastic. The DWM1001 module requires a precise initialization of the parameters to ensure optimal operation. The key parameters include UWB channel selection, pulse repetition frequency (PRF), preamble length, preamble acquisition chunk (PAC), preamble code, and data rate (Table 1). The UWB channel determines the frequency at which the module operates. The DWM1001 module is equipped with a PCB Trace Monopole Antenna (Decawave’s WB003 – MiniHoe), which is optimized for UWB Channel 5 (operating near 6.5 GHz). Therefore, this study utilized a UWB sensor on Channel 5 with a center frequency of 6.5 GHz32. The data rate of the module was set to 6.8 Mbit/s, which enables high-speed transmission and maintains reliable communication. The PRF controls the rate at which UWB pulses are transmitted and enables a trade-off between energy efficiency and signal clarity. This study determined the PRF to be 64 MHz for signal clarity, selecting 64 MHz over 16 MHz for better noise reduction and signal stability. The preamble length, which is recommended to be set to 128 at a data rate of 6.8 Mbit/s, is responsible for the signal acquisition and synchronization to ensure a stable connection and accurate first-path detection. The PAC, recommended to be set to a size of eight for a preamble length of 128 symbols, enhances the detection accuracy and robustness. The preamble code uniquely identifies the UWB signal with a value of 10 available for a PRF of 64 MHz on Channel 5. Further details regarding the UWB channel numbers and preamble codes are provided in the IEEE 802.15.4-2011 standard33. The DW1000 User Manual provides the recommended parameter values for the PRF, PAC, and data rate30. A tripod adjustable between 0.5 m and 2.1 m in height supported the transmitter, allowing data collection at various antenna elevations. Adjusting the antenna elevation is crucial for investigating the multipath effect because the elevation difference between the tag and anchor determines the UWB propagation signals reflected by the surface. The comparison of the height differences in the measurements is explained in detail in Section 2.4. A BOSCH GLM100C laser measurement sensor with an accuracy of ±1.5 mm served as ground truth for analyzing the range data32. A direct wired connection using the UART protocol transferred the measurements from the UWB device to a host PC to ensure precise logging of the static range observations. The data were collected on a host PC via a wired UART connection (Fig. 1). A BOSCH GLM100C laser measurement sensor was used as the ground truth to analyze the range data in a static environment34.

A dynamic measurement system was constructed by modifying a Rover Zero 2 2WD mobile robot (Rover Robotics, USA) to minimize human errors and integrate multiple sensors for robust data collection (Fig. 3). Specifically, the mobile robot operated within the maximum speed limit of 2.5 m/s and used a closed-loop PID velocity controller described in the official rover specification to perform both straight-line motion and turning maneuvers using differential wheel speeds. The platform was equipped with an Intel RealSense D435i stereo camera, a VectorNav VN-100 IMU, a Ublox ZED-F9P global navigation satellite system (GNSS) receiver (configured for RTK corrections), and an Intel NUC (i7-1165G7) to provide real-time position and visual information. Four UWB anchors (transmitters) were deployed within the test site, and a single UWB tag (receiver) was mounted 1.0 m above ground level on the robot. An adequate separation between the UWB and GNSS antennas was maintained to minimize the mutual interference. The robot then navigated various paths including obstruction-rich areas and multiple trajectories, to evaluate the UWB behavior in realistic motion scenarios. An RTK-corrected GNSS system with an accuracy of less than 3 cm was used as a position reference35. A GNSS base station transmitted the RTK corrections at 1Hz via a Wi-Fi module. The GNSS mobile station attached to the robot received the signal. PC 1 collected the range data from each UWB anchor through wired connections and was linked to the GNSS base station (Fig. 1(b)). PC 2 was mounted on the robot, managed the GNSS mobile station, IMU, and UWB tag. Both the PCs were synchronized at each iteration using the Network Time Protocol (NTP) over a direct WLAN link to ensure consistent timestamps for integrating the UWB ranges and GNSS coordinates.

Data processing

This section presents the details of processing raw sensor data to enable the analysis of the RSS and accuracy, as well as the application in robot control. The processing pipeline comprises three main components: RF quality assessment, localization benchmarks, and GNSS processing (Fig. 4). First, the CIR-based RSS estimation method is adopted to investigate the RF quality. This process is crucial for assessing the effects of multiple paths and NLOS (Fig. 4(a)). Second, localization benchmarks are introduced to demonstrate the utilization of the dataset. These benchmarks served as effective references for comparing and evaluating novel localization algorithms for the dataset (Fig. 4(b)). Third, the RTK-corrected GNSS is processed to accurately determine the precise position of the tag, enabling the evaluation of the localization accuracy. Furthermore, GNSS data provides essential position information for real-time robot control and navigation (Fig. 4(c)).

The RSS serves as the primary indicator for evaluating the UWB transmission quality (Fig. 4(a)). However, the Decawave DWM1001 module does not provide a dedicated hardware register for the RSS. An indirect value can be inferred from the maximum CIR power, which represents a frame quality metric derived from the DW1000 registers20,36. The near-equivalent RSS values are determined from the parameters defined by the IEEE 802.15.4 standard UWB system30. Therefore, the RSS can be estimated as

where \(c\), \(N\), and \(A\) represent the maximum CIR power value obtained through a leading-edge detection algorithm, the RX preamble accumulation count (RXPACC), and a predefined constant for RSS estimation (121.74 for a 64 MHz PRF), respectively. All the three parameters are accessible from the DW1000 registers, enabling direct computation of the RSS. Therefore, a CIR-based RSS estimate can be used to assess the UWB sensor performance in outdoor environments.

Two localization methods are used to evaluate and validate the dataset (Fig. 4(b)). The first is the LS approach, which relies solely on the UWB range data. The general LS solution for the position of the tag \({[\begin{array}{ccc}{x}_{T} & {y}_{T} & {z}_{T}\end{array}]}^{T}\) is given by

where \({\bf{H}}\) and \(\vec{x}\) are the matrices computed from the measured range data and specific anchor locations, respectively. Matrix \({\bf{H}}\) is defined as

where \({x}_{i}\), \({y}_{i}\), \({z}_{i}\) denote the anchor locations. Vector \(x\) contains the squared distance differences, and is expressed as:

where \({d}_{i}\) denotes the UWB-measured distance between the tag and \(i\)-th anchor. The distance \({d}_{i}\) is computed internally within the UWB anchors using \({d}_{i}={T}_{{of}}\cdot c\), where \({T}_{{of}}\) and \(c\) denote the output of Eq. (6) and speed of light. Note that the LS approach is computationally efficient and straightforward, whereas accuracy may degrade when the anchor spacing is suboptimal or when noise affects the range measurements37.

The second method, ESKF27, is utilized to verify the availability and performance of multimodal localization. This method combines IMU and UWB measurements to address the limitations of range-only localization. Note that the ESKF is particularly effective under conditions where high-frequency IMU measurements are available38. The IMU readings including accelerations and angular velocities refine the tag state estimates to enhance the overall accuracy. In the ESKF, state estimation is achieved in two steps: prediction and correction. The prediction step computes the nominal state using high-frequency IMU measurements. The correction step estimates the error state using the UWB ranging data to correct the nominal state. The prediction step is executed as

where \({{\bf{R}}}_{{\bf{k}}}\), \(\triangle t\), \({\vec{v}}_{k}\), \({\vec{a}}_{k}\), \(\vec{g}\), and \({\vec{p}}_{k}\) denote the rotation matrix, gyroscope measurement, time increment, velocity, accelerometer measurement, gravity vector, and position at time \(K\), respectively. Note that the rotation matrix \({{\bf{R}}}_{{\bf{k}}}\) is computed by gyroscope measurements. Then, a correction step is performed to estimate the error state using the UWB ranging measurements. The correction step is expressed as follows:

where \(z\), \({\vec{p}}_{k}\), \({\vec{p}}_{{anchor}}\), \(v\), \(\delta {\vec{x}}_{k}\), \({\hat{\vec{x}}}_{k}\), and \(h\left({\hat{\vec{x}}}_{k}\right)\) denote the range measurement, predicted position, anchor's position, measurement noise, error state, nominal state, and predicted measurement, respectively. Note that \(\delta {\vec{x}}_{k}\) is injected into \({\hat{x}}_{k}\) to compute the true state. This sensor fusion-based localization method is particularly effective under challenging conditions that degrade the performance of basic range-based methods39.

Third, the GNSS measurements were aligned within a global coordinate system to enable the comparison of the GNSS and UWB data (Fig. 4(c)). This process was aimed at determining an accurate tag position using RTK-corrected GNSS measurements. Figure 5 illustrates the coordinate alignment diagram between GNSS and UWB. The base anchor is placed in the global coordinates {\({\rm{W}}\)}, and Eq. (13) is used to transform the GNSS-measured tag positions into {\({\rm{W}}\)}. This procedure involves converting the LLA coordinates into a Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) coordinate system {\({{\rm{U}}}_{1}\)}, a Cartesian coordinate system based on the WGS84 ellipsoid model40. The Aligned UTM coordinate {\({{\rm{U}}}_{2}\)} is defined to align the GNSS data in {\({{\rm{U}}}_{1}\)} with {\({\rm{W}}\)}, which shared the same \(x\)-axis as {\({\rm{W}}\)}. The tag position in {\({\rm{W}}\)} \({p}_{{tag}}^{{\bf{W}}}\) is computed as follows:

where \({{\bf{T}}}_{{\boldsymbol{* }}}^{{\boldsymbol{* }}{\boldsymbol{* }}}\), \({{\bf{R}}}_{{\boldsymbol{* }}}^{{\boldsymbol{* }}{\boldsymbol{* }}}\), \({t}_{* }^{* * }\), and \({p}_{{tag}}^{{\bf{B}}}\) denote the transformation matrix, rotation matrix, translation vector of the {*} to {**} coordinates, and tag position in the robot base coordinate {\({\rm{B}}\)}, respectively. Note that the translation matrix of \({{\bf{T}}}_{{{\bf{U}}}_{{\boldsymbol{1}}}}^{{{\bf{U}}}_{{\boldsymbol{2}}}}\) is zero and that the rotation matrix of \({{\bf{T}}}_{{{\bf{U}}}_{{\boldsymbol{2}}}}^{{\bf{W}}}\) is an identity matrix. \({t}_{{{\bf{U}}}_{{\boldsymbol{2}}}}^{{\bf{W}}}\) is measured manually using BOSCH laser measurements for each experiment. \({t}_{{\bf{B}}}^{{{\bf{U}}}_{{\boldsymbol{1}}}}\) is the GNSS measurement converted to UTM coordinates. \({{\bf{R}}}_{{\bf{B}}}^{{{\bf{U}}}_{{\boldsymbol{1}}}}\) is computed by IMU/attitude and heading reference system (AHRS) measurements with a 2.0° RMS heading accuracy. Therefore, the main challenge in calculating \({p}_{{tag}}^{{\bf{W}}}\) is determining \({{\bf{R}}}_{{{\bf{U}}}_{{\boldsymbol{1}}}}^{{{\bf{U}}}_{{\boldsymbol{2}}}}\). The rotation angle \(\gamma \) (Fig. 5) adjusts the yaw component utilizing the fact that both {G} and {W} share the same \(z\)-axis, whereas roll and pitch are then disregarded. Therefore, only the \(\gamma \) value is required to compute \({{\bf{R}}}_{{{\bf{U}}}_{{\boldsymbol{1}}}}^{{{\bf{U}}}_{{\boldsymbol{2}}}}\) and is extracted after the line following process. Note that the parking line is aligned with the \(x\)-axis \({\left[\begin{array}{ccc}1 & 0 & 0\end{array}\right]}^{T}\) in the global coordinate system {W}, which serves as the driving direction. The yaw angle between {G} and {W} is computed at 10 Hz during the line following. Finally, \(\gamma \) is represented by averaging the accumulated yaw values to decrease noise. In this process, the image processing and control algorithms are utilized for the measurement system. Detailed explanations of the processing steps are beyond the scope of this discussion and not depicted herein for the sake of brevity. The image processing method addresses Gaussian blur and contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization to enhance the visibility and morphological operations to extract the parking line. The control algorithm computes the orientation and velocity commands in real time using the extracted line features and PID control to ensure stable navigation.

Field experiments

Two field experiments were conducted to acquire effective static and dynamic data for each scenario. The common experimental condition for these experiments was that the UWB measurements were performed in the parking lot of the Hanyang University’s Engineering Center in South Korea, which is a general outdoor environment with few obstacles and flat asphalt. Both the field experiments utilized MDEK1001 Kits and standard office partitions to record data in NLOS environments. These partitions disrupt the direct path of radio propagation, thereby causing RSS loss and an increase in range errors owing to multipath effects.

The first experiment was conducted under static scenarios to measure the multipath effect on the RSS and range data. This experiment was aimed at investigating UWB radio propagation, which is mainly affected by the ground surface, RSS discrepancies, and range errors in NLOS/LOS environments. Ground reflection interferes with the received signals and reduces the received power to a value below the minimum detectable threshold of the receiver. This phenomenon creates regions where no signal is received (known as Fresnel zones). Specifically, UWB signals are subject to fading due to multipath and this ground-induced fading is influenced by the height of the UWB nodes above the ground and distance between the nodes17. Therefore, the transmitter height was adjusted to examine how the elevation above the ground influenced the measured ranges and RSS. In contrast, the receiver height was fixed at 1 m above the ground to replicate pedestrians or objects having the tag. Moreover, this field experiment included both LOS and NLOS scenarios to analyze how such obstructions affect UWB signals. Obstructions between UWB nodes (influencing the RSS and range error) were installed to replicate unforeseen NLOS scenarios such as trees, building exteriors, pedestrians, or vehicles in outdoor environments. Thus, the dataset provides a more comprehensive understanding of the UWB behavior under diverse conditions.

Figure 6 shows a schematic of the first field experimental procedure (Fig. 6(a)) and the setup of the experimental environment for the real-world experiments (Fig. 6(b)). The experiment was conducted using a UWB receiver–transmitter pair. The transmitter height was elevated from 0.5 m to 2.0 m in 0.125 m increments to examine the multipath effects based on sensor heights (Fig. 6(a)). Heights below 0.5 m yielded severely degraded UWB signal quality, thereby preventing reliable data acquisition. Therefore, this study collected measurements above this threshold. The horizontal distance from the transmitter increased from 2 m to 60 m in 2 m increments. Ninety measurements were collected over nine seconds at each distance (10 Hz sampling rate). Furthermore, additional trials introduced two standard office partitions between the transmitter and receiver to analyze NLOS environments in an identical outdoor static setting. Each partition was positioned at distances of 0.5 m and 2.0 m in front of the transmitter, with a width, height, and thickness of 0.8 m, 1.42 m, and 0.05 m, respectively (Fig. 6(b)). Each partition consisted of an internal wooden core, was surfaced with a thin (< 0.001 m) silk fabric layer on both sides and had a metal frame along the perimeter. This obstruction prevented measurements at 2 m. Therefore, the NLOS data were collected from 4 m to 60 m in 2 m increments. A BOSCH GLM100C laser measurement sensor was used to accurately verify the distance measured from each receiver position.

The second experiment was performed under dynamic conditions to collect multimodal data. This field experiment was aimed at collecting a test dataset to verify the localization algorithms and evaluating multiple anchor configurations in two distinct trajectories. The experiment employed a mobile robot platform (Fig. 3) to replicate realistic motion paths and collect multimodal data including IMU, GNSS, and UWB. Both LOS and NLOS scenarios were measured to analyze the obstacle effects by utilizing the objects used in the first field experiment. Note that the minimum number of anchors required for 3D localization is three. Four anchors were deployed in this study to enhance stability and the localization accuracy. This configuration also allows potential users to selectively utilize either three or four anchors depending on their algorithmic requirements or evaluation scenarios, thereby offering flexibility for benchmarking and comparative studies.

Figure 7 illustrates the simplified diagrams and configurations of the experiments under dynamic conditions. The four anchors were positioned randomly in a region with a width and depth of 1.74 m and 5.155 m, respectively. Trajectory A positioned the tag primarily in front of the anchor array (Fig. 7(a)). Meanwhile, Trajectory B was designed to capture tag movements from multiple directions, allowing a broader range of data near the anchor placements (Fig. 7(b)). Each trajectory was measured further in two separate anchor configurations to investigate the effect of placement variations on the localization accuracy.

The accuracy of tag position estimation depends significantly on the anchor configuration. Specifically, anchor configurations can be assessed using dilution of precision (DOP), which measures how the anchor geometry influences the positioning accuracy. This study adopted the PDOP to guide anchor placement because this indicator effectively quantifies the effect of anchor geometry on positioning accuracy41. For each trajectory, configurations with favorable PDOP were selected to ensure the stable positioning scenarios within a limited anchor deployment area. Table 2 summarizes the anchor coordinates of the global coordinate system, {\(W\)}. For example, in Trajectory A (case 1), the four anchors were mounted at locations (2.58, 0.87, 1.97), (2.58, -0.87, 1.97), (2.58, -0.87, 0.5), and (0.69, 0.87, 0.5). Each subsequent case placed anchors at distinct positions. This enabled varied measurement scenarios and, thereby, promoted a robust evaluation of the UWB performance under dynamic conditions.

Moreover, office partitions (the obstructions shown in Fig. 7) were installed to generate NLOS environments. Trajectory A was designed to have an overall NLOS path, whereas Trajectory B was set up to create partial NLOS environments. Therefore, the locations and dimensions of the obstructions were determined based on these objectives. In Trajectory A, three office partitions (each having a width of 0.8) were placed in a row at the location (4.3, 0) with a total width of 2.4 m to obstruct the overall trajectory of the robot (Fig. 7(a)). In Trajectory B, three partitions were installed at the locations (-5, 5, 0), (5, 5, 0), and (-5, -5, 0) (Fig. 7(b)). Figure 7(c) shows the configuration of the environment of trajectory B. Here, the blue boxes indicate the obstacle locations, and the red boxes indicate the mobile robot waypoints. Therefore, the dataset assembled in these environments and anchor layouts provides a resource for verifying the robustness of the localization algorithms.

Data Records

The dataset is publicly available for download from the Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29605775)42 connected with GitHub to explain the quick start guidance of dataset (https://github.com/cucudasluv/UWB-dataset). This section provides detailed information on the curated data collected from the field experiments with technical validation codes to help researchers conveniently locate and utilize the necessary data. Specifically, the data structures and components in static and dynamic environments are described to ensure a clear understanding of data organization and facilitate efficient usage. The overall dataset was stored in comma-separated value (CSV) files available for data analysis in MATLAB and Python. Furthermore, dynamic measurements provided the data in.bag files to process the data and verify the proposed localization method in real time. The data are freely available for processing and visualization using the technical validation codes provided in the repository.

Figure 8 shows the data organization of the static and dynamic categories. Static measurements contain both LOS and NLOS folders, with subdirectories named according to the transmitter height above the ground level (Fig. 8(a)). The anchor height folders are named as height_{value}.csv. These range from 0.5 m to 2.0 m and are recorded in increments of 0.125 m. Each subdirectory contains measurement sets at horizontal distances up to 60 m that are recorded in 2 m increments and stored in.csv files named {horizontal distance}m.csv. Data collection started at 4 m and 2 m for the LOS measurements. For example, the file path /Static_measurements/LOS/height_0.5m/2_m.csv corresponds to data measured in a static LOS environment where the transmitter height is 0.5 m and the horizontal distance between UWB nodes is 2 m. Specifically, each CSV file contains 90 data points for repeatability. The mean and standard deviation of the RSS and range are provided to facilitate statistical analysis. Table 3 lists the complete set of data indices gathered during the static measurements.

Dynamic measurements were collected in both LOS and NLOS environments (Fig. 8(b)). The dataset comprises two distinct tag trajectories: Trajectory A and Trajectory B. Each trajectory includes two cases representing different anchor configurations. The subfolder names Trajectory A, Trajectory B, Case 1, Case 2, Case 3, and Case 4 follow the notation presented in Table 2. Each case folder contains raw GNSS, IMU, and UWB data in conjunction with localization outputs from the LS and ESKF methods. This dataset is available in both.bag and.csv formats to support real-time applications and enhance the versatility. Specifically, the combined.bag file integrates all the collected sensor data in a time series through ROS-based sensor recording. The recorded sensor data in the.bag format includes GNSS measurements, UWB ranging with RSS, localization outputs of the LS and ESKF methods, and IMU/AHRS data (Table 4). The GNSS measurements contain raw RTK-corrected data in LLM coordinates and data processed using Eq. (13). The /dwm1001/anchor* topic contains anchor ID, fixed anchor position, RSS, and ranging measurements. These topics were customized for these datasets. Thus, the customized format is provided in the technical_validation folder, which is necessary for an ROS-based analysis. The visualization topic /dwm1001/markers was also provided to identify the specific anchor locations in the ROS visualization tool of Rviz. Overall, the dynamic measurements including the IMU, LS, and ESKF results contain timestamp values to ensure time-based analysis.

The UWB data from four anchors are provided in the.csv format: A3.csv, A5.csv, A9.csv, and A12.csv. These files also include timestamps, anchor locations, ranges, and RSS values. Raw GNSS and IMU data are stored separately in gnss.csv and imu.csv. The localization results are saved in LS.csv and ESKF.csv. These contain the \(x\)-, \(y\)-, and \(z\)-coordinates in conjunction with timestamps. Trajectory.csv provides the processed GNSS data to evaluate the localization algorithms (Fig. 4(b)). Data_visualization.png file provides a 2D image that visualizes both localization outputs of LS and ESKF and processed GNSS data.

Scripts are available for technical validation to analyze both static and dynamic measurements. The Technical_validation folder comprises RSS_analysis.py, ranging_error_analysis.py, and localization_error_analysis.py for.csv files, and eskf.py and least_square.py for.bag files (Fig. 8(c)). RSS_analysis.py and ranging_error_analysis.py analyze and visualize the differences between the NLOS and LOS environments in static RSS and ranging measurements to investigate multipath effects. The localization_error_analysis.py script computes the RMSE between the RTK-GNSS and localization outputs. This script generates 2D visualizations to evaluate the performance of the localization methods. The eskf.py and least_square.py scripts, compatible with ROS, implement localization methods using ranging measurements from the four anchors. The technical validations of the measurements are explained in detail in Technical Validation section.

Technical Validation

This section presents the practicality of the acquired datasets for outdoor multipath effect analysis depending on the ranging, RSS, and localization algorithm developments. First, static measurements in both LOS and NLOS environments were examined to evaluate the impact of the multipath effects of obstructions and ground reflections. This analysis investigated the RF quality and occurrence of Fresnel zones based on the transmitter height. Second, the ranging errors in static measurements were analyzed in both LOS and NLOS environments. This subsection compares the outdoor ranging errors of the LOS and NLOS scenarios at various horizontal distances and verifies the multipath effects induced by ground reflections and obstacles. Third, benchmark algorithms including LS and ESKF were used for localization. This subsection evaluates the localization performance under distinct anchor configurations and outlines the effectiveness of the multimodal localization method through a positioning accuracy analysis.

RSS analysis

This section explains in detail the RSS loss caused by obstacles and irregular variations in the RSS owing to ground reflections. Outdoor measurements generally deviate from the free-space path loss (FSPL) model due to multipath effects, particularly ground reflections43. The FSPL represents the theoretical signal attenuation in an ideal environment that is devoid of obstructions and reflections. The FSPL \({L}_{{FS}}\) is expressed as

where \(d\), \(\lambda \), and \(K\) denote the distance between the transmitter and receiver, signal wavelength, and system gains, respectively. \({L}_{{FS}}\) increases predictably as a function of the logarithm of the transmitter–receiver distance (Eq. (14)). However, real-world outdoor measurements generally do not adhere to the FSPL model owing to the influence of ground reflections. The sensor height above the ground further amplifies or mitigates multipath effects, leading to variations in signal behavior at different elevations. Figure 9 illustrates RSS variations with distance for sensor heights of 0.75 m and 1.5 m under both LOS and NLOS. The overall trend remains similar across the LOS and NLOS environments. Meanwhile, the NLOS measurements exhibit a consistently lower RSS. Specifically, the average RSS over 60 m decreases by 2.3 dBm at a sensor height of 0.75 m and by 2.5 dBm at 1.5 min NLOS environments, compared with LOS environments. This result emphasizes the radio propagation disturbance of the signal strength caused by obstructions (Fig. 9). Note that signal disruptions were prominent below 1.5 m, where direct path obstructions significantly influenced RSS, because the obstacle height was 1.42 m. However, the impact of obstacles reduced significantly and multipath effects became minimal when the sensor was placed above 1.5 m.

Fresnel holes, where UWB communication was severely disrupted, were identified by two concurrent criteria: a data acquisition rate of fewer than 10 measurements per minute and a received signal strength weaker than −97 dBm. Note that significant disruptions appeared in the received signal at a sensor height of 1.5 m, indicating that certain heights can significantly amplify the interference of ground reflections with severely degraded communication (Fig. 9(b)). Specifically, a Fresnel zone was detected at distances between 54 m and 56 m at a sensor height of 1.5 m in LOS environments, whereas NLOS communication failed beyond 52 m (where data could not be collected). Meanwhile, Fresnel zones were not observed at a sensor height of 0.75 m, and RSS remained stable across a 60 m range under both LOS and NLOS environments. These discrepancies in Fresnel zone formation depending on sensor height demonstrate the significant dependence of the RSS on the sensor placement. This result indicates that UWB sensors should be installed at optimal heights to enhance the signal strength and stability. Note that the sensor height should be selected considering the existence of Fresnel zones to enable a large coverage area compared to NLOS environments or suboptimal sensor heights.

Ranging error analysis

This section analyzes the ranging errors originating from multipath effects under outdoor conditions. Measurements conducted under outdoor conditions revealed a consistent tendency to overestimate the actual distance for the DWM1001 device depending on the separation between the tag and anchor. A feasible explanation for this overestimation is multipath propagation, in which signals are reflected off the surfaces before reaching the receiver. These additional paths extend the signal travel time and cause the measured distance to exceed the actual LOS measurement.

The ranging error is defined as the signed error, calculated by subtracting the laser-based reference distance from the measured distance by the DWM1001 module. Figure 10 illustrates an evident increase in ranging errors as the tag–anchor distance increases in both LOS and NLOS environments. Specifically, the ranging error in the LOS environment attained a maximum of 0.273 m at a horizontal distance of 60 m. This result indicates that the extended propagation paths significantly increased the measured distances, a phenomenon primarily attributed to multipath effects. In NLOS environments, the maximum error increased to 0.352 m at an equal horizontal distance of 60 m. The more complex signal paths under NLOS environments attenuated the received power and introduced a larger discrepancy between the true distance and measured value.

The dependence of ranging accuracy on the sensor height, which varies with the propagation length, was also examined. Note that the variations in transmitter height generated inconsistencies in the ranging error. Specifically, the average ranging error at a transmitter height of 0.5 m in the NLOS environments was higher than that for LOS by 0.061 m, corresponding to a 28.44% increase. The error difference attained 0.089 m at a height of 1.125 m (an increase of 41.73%). The smallest recorded error was 0.176 m at a transmitter height of 1.125 m, whereas the maximum error was 0.234 m at 0.875 m. These variations imply that the multipath effects are highly sensitive to the vertical alignment of the transmitter, highlighting the importance of a meticulous UWB sensor placement. The presented data serve as a reference for assessing the anticipated variations in the ranging accuracy owing to multipath effects in comparable outdoor environments. The distance and sensor height have emerged as key factors that influence measurement discrepancies, reinforcing the need for strategic sensor deployment to mitigate multipath-induced errors.

Localization analysis

This section provides researchers with benchmark methods for developing localization algorithms. Localization analysis evaluates the accuracy of the two localization algorithms (LS and ESKF) under multiple anchor configurations by comparing their results with the processed RTK-GNSS data. Figure 11 presents the outputs of the two proposed localization methods and the GNSS-RTK measurements for each case, as described in Table 2.

Note that accuracy enhancement originates from the elimination of obstructions and multimodal sensor fusion methods. Specifically, Cases 1, 2, 3, and 4 in the LOS environments yielded LS RMSE values of 1.58 m, 2.87 m, 0.79 m, and 0.87 m, whereas the values of 1.34 m, 1.91 m, 0.84 m, and 0.89 m were yielded in the NLOS environments, respectively (Table 5). Note that the few positioning points cause large positioning error in Trajectory A and increased RMSE values (Case 1, 2). Trajectory B, measured in relatively small area, shows the stable positioning outputs and identify the increased RMSE in NLOS environments (Case 3, 4). Meanwhile, Increased positioning errors in the NLOS environments were identified notably for the ESKF (Case 2, 3, 4), indicating that the obstructions caused an overestimation of the ranging data and, ultimately, further localization errors. Significantly, the ESKF performs particularly well in longer-range or cluttered environments, where range errors from LOS/NLOS transitions degrade the performance of standalone range-based methods. The ESKF RMSE values in the LOS environments were 1.34 m, 1.23 m, 0.79 m, and 0.70 m, respectively (Table 5). The ESKF approach yielded improvements of approximately 15.2%, 57.1%, 0.0 %, and 19.5% in Cases 1–4. Furthermore, the ESKF enhanced the positioning accuracy of 14.2%, 16.2%, and 9.0% in Case 1, 2, and 4, respectively. These results demonstrate that the ESKF is effective for localization in inferior environments with significant multipath errors and unfavorable anchor configurations causing further localization errors. The observed advantage of the ESKF over LS is primarily attributed to the IMU-based motion constraints. These reduce noise and resolve ambiguities when direct ranging becomes unreliable. In particular, the ESKF continuously corrects the state estimate by utilizing inertial data to fill the gaps left by multipath conditions or inconsistent anchor measurements. Specifically, the error reductions in the NLOS environments measured for each case were 28.2 %, 35.3%, 12 %, and 7%, respectively. Thus, the ESKF provides more stable position estimates than LS, thereby reducing large deviations in localization.

Figure 12 illustrates the localization errors of the LS and ESKF in Case 1 along the \(x\)-, \(y\)-, and \(z\)-axes. The results of the LS method are represented by the green lines, whereas the ESKF estimates are shown in red. The trajectories obtained from the RTK-GNSS measurements are plotted in black for direct comparison. Interestingly, the RMSE of each x, y, and z axes is 0.24 m, 1.01 m, and 1.19 m for the LS method, whereas the RMSE of ESKF is 0.26 m, 1.08 m, and 0.69 m, respectively. Note that an effective error reduction, particularly along the z-axis, occurred through sensor fusion. The ESKF method effectively compensates for low vertical coverage by integrating IMU data, thereby reducing the error generated when the anchors incompletely enclose the measurement environment in three dimensions. Consequently, the appropriate anchor configuration with the multimodal localization method provides a more dependable localization system, in which the combined solution compensates for the suboptimal anchor spacing and maintains a lower RMSE under varying operating conditions.

Usage Notes

This section presents both the potential applications and inherent limitations of the constructed dataset, aiming to support and guide subsequent research efforts in the field of wireless localization. Specifically, the dataset is expected to be beneficial in the following three primary applications: ranging error mitigation, localization accuracy improvement, and anchor placement optimization. Furthermore, limitations such as the use of a single tag and the lack of consideration for antenna orientation effects are also discussed to ensure practical and transparent use. These application scenarios and identified limitations collectively provide meaningful guidance for future research and offer a foundation for further enhancement of the dataset.

First, the ranging error can be mitigated using UWB measurements through two approaches: training machine learning models and modeling sensor characteristics using probabilistic methods44,45. Specifically, statistical features extracted from ranging and RSS data are used in machine learning methods to classify LOS and NLOS environments, thereby reducing incorrect measurements11. Probabilistic UWB sensor models constructed from real-world RSS and time-of-flight measurements in LOS/NLOS environments can also be integrated into a Bayesian filtering framework to mitigate ranging errors46. These methods can utilize the provided dataset, including the ranging and RSS data, to effectively mitigate the concerns of ranging errors in UWB measurements originating from multipath effects.

Second, the localization accuracy can be improved through sensor fusion methods with IMU and UWB data because this information could correct the accuracy degradation in UWB-only localization in NLOS environments47. Specifically, ref. 48 adopted the invariant extended Kalman filter that integrates IMU data into UWB measurements to enhance the UWB localization accuracy. Significant improvements were observed in the systemic analysis when the heading estimation was compared with that of the ESKF. The dataset, which contains synchronized IMU and UWB data collected in dynamic scenarios, can be used for these applications to develop and validate sensor fusion algorithms aimed at effectively improving the localization accuracy.

Third, the anchor placement can be optimized by determining the anchor configurations that minimize localization errors15,49. The conventional study constructs NLOS error models based on experimental data and then incorporates these models into a block-coordinate-wise minimization-based optimization process that balances the geometric anchor positions and NLOS effects to optimize the anchor placement across scenarios50. The dataset, which provides various anchor arrangements in static and dynamic outdoor environments, can facilitate accurate UWB measurement modeling and thereby support anchor placement optimization to improve the localization accuracy.

The current dataset presents several limitations that should be acknowledged for accurate interpretation and responsible use. These limitations include the use of a single UWB tag, the absence of antenna orientation considerations, and the constrained number of anchors. Specifically, the reliance on a single tag restricts the generalizability of the results and real-world applications51. The impacts of antenna orientation on UWB ranging accuracy and received power are not addressed, omitting consideration of a key parameter relevant to the radio propagation22. Moreover, the fixed number of anchors may compromise localization robustness in larger or obstructed environments where greater geometric diversity is required52. Future work will expand the dataset to support multi-tag scenarios, incorporate antenna orientation variations, and evaluate anchor configurations under diverse spatial conditions.

In summary, the dataset provides comprehensive static and dynamic UWB measurements across scenarios. This dataset includes ranging, RSS, and synchronized IMU data, which enable researchers to mitigate ranging errors, enhance localization accuracy, and optimize anchor placements without additional preprocessing. However, the limitations including the use of a single UWB tag, the lack of antenna orientation considerations, and the constrained number of anchors are discussed to ensure responsible use and to guide future improvements. The GitHub repository provides example scripts and instructions for immediate data analysis, visualization, and implementation to support the application system that deploys UWB in outdoor environments42.

Code availability

The Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29605775) and dedicated GitHub (https://github.com/cucudasluv/UWB-dataset) provide permanent access to the dataset and the pipeline employed for data processing, including GNSS coordinate conversion; LS- and ESKF-based localization algorithms for ROS; and analysis routines for localization errors, ranging errors, and RSS visualizations in LOS and NLOS environments. The software was released under the Apache-2.0 License, ensuring transparent and reproducible use of the code.

References

Jiménez, A. R. & Seco, F. Finding objects using UWB or BLE localization technology: A museum-like use case. In 2017 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN) 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1109/IPIN.2017.8115865 (2017).

Xianjia, Y., Qingqing, L., Queralta, J. P., Heikkonen, J. & Westerlund, T. Applications of UWB networks and positioning to autonomous robots and industrial systems. In 2021 10th Mediterranean Conference on Embedded Computing (MECO) 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/MECO52532.2021.9460266 (2021).

Huang, J., Gautam, A., Choi, J. & Saripalli, S. WiDEVIEW: An ultrawideband and vision dataset for deciphering pedestrian-vehicle interactions. Preprint at, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.16057 (2023).

Cheng, T., Venugopal, M., Teizer, J. & Vela, P. A. Performance evaluation of ultra wideband technology for construction resource location tracking in harsh environments. Autom. Constr. 20(8), 1173–1184, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2011.05.001 (2011).

Fakhoury, S. & Ismail, K. Ultra-wideband-based time occupancy analysis for safety studies. Sensors 23, 7551, https://doi.org/10.3390/s23177551 (2023).

Peserico, G., Fedullo, T., Morato, A., Tramarin, F. & Vitturi, S. Ultra-wideband for distance measurement and positioning in functional safety applications. In 2022 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 & IoT (MetroInd4.0&IoT) 360–365, https://doi.org/10.1109/MetroInd4.0IoT54413.2022.9831662 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. UWB sensor-based indoor LOS/NLOS localization with support vector machine learning. Sensors. 23, 2988–3004, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2022.3232479 (2023).

Morawska, B., Lipiński, P., Lichy, K., Koch, P. & Leplawy, M. Static and dynamic comparison of Pozyx and DecaWave UWB indoor localization systems with possible improvements. In 2021 Computational Science – ICCS: 21st International Conference (ICCS) 582–594, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77970-2_44 (2021).

Risset, T., Goursaud, C., Brun, X., Marquet, K. & Meyer, F. UWB ranging for rapid movements. In 2018 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN) 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1109/IPIN.2018.8533820 (2018).

Maranò, S., Gifford, W. M., Wymeersch, H. & Win, M. Z. NLOS identification and mitigation for localization based on UWB experimental data. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 28, 1026–1035, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2010.100907 (2010).

Barral, V., Escudero, C. J., García-Naya, J. A. & Maneiro-Catoira, R. NLOS identification and mitigation using low-cost UWB devices. Sensors 19, 3464, https://doi.org/10.3390/s19163464 (2019).

Delamare, M., Boutteau, R., Savatier, X. & Iriart, N. Static and dynamic evaluation of an UWB localization system for industrial applications. Sci. 2, 23, https://doi.org/10.3390/sci2020023 (2020).

Zhang, Y. & Liu, M. Node placement optimization of wireless sensor networks using multi-objective adaptive degressive Ary number encoded genetic algorithm. Algorithms 13, 189, https://doi.org/10.3390/a13080189 (2020).

Ma, H., Lou, P. & Chen, M. UWB anchor deployment optimization based on improved artificial rabbits optimization. In 2023 5th International Academic Exchange Conference on Science and Technology Innovation (IAECST) 50–53, https://doi.org/10.1109/IAECST60924.2023.10503035 (2023).

Li, J., Xiu, C. & Yang, D. An optimal deployment method of UWB positioning base-station. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. X-3/W1-2022, 85–91, https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-annals-X-3-W1-2022-85-2022 (2022).

Kristem, V., Niranjayan, S., Sangodoyin, S. & Molisch, A. F. Experimental determination of UWB ranging errors in an outdoor environment. In 2014 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC) 4838–4843, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC.2014.6884086 (2014).

DecaWave. APS017: Maximising range in DW1000 based systems. Qorvo https://www.qorvo.com/products/d/da008450 (2024).

Harun, A. et al. Antenna positioning impact on wireless sensor networks deployment in agriculture. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 7, 55–60, https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/en/publications/antenna-positioning-impact-on-wireless-sensor-networks-deployment (2013).

Zhao, W., Goudar, A., Qiao, X. & Schoellig, A. P. UTIL: An ultra-wideband time-difference-of-arrival indoor localization dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 43, 1443–1456, https://doi.org/10.1177/02783649241230640 (2024).

Bregar, K. Indoor UWB positioning and position tracking data set. Sci. Data. 10, 744, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02639-5 (2023).

Vey, Q., Dalcé, R., Van Den Bossche, A. & Val, T. Indoor UWB localisation: LocURa4IoT testbed and dataset presentation. In 2022 IEEE 47th Conference on Local Computer Networks (LCN) 258–260, https://doi.org/10.1109/LCN53696.2022.9843513 (2022).

Chen, J., Raye, D., Khawaja, W., Sinha, P. & Guvenc, I. Impact of 3D UWB antenna radiation pattern on air-to-ground drone connectivity. In 2018 IEEE 88th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC-Fall) 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/VTCFall.2018.8690726 (2018).

Arjmandi, Z., Kang, J., Park, K. & Sohn, G. Benchmark dataset of ultra-wideband radio-based UAV positioning. In 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC) 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1109/ITSC45102.2020.9294440 (2020).

Morón, P. T. et al. Benchmarking UWB-based infrastructure-free positioning and multi-robot relative localization: Dataset and characterization. In 2023 IEEE Sensors Applications Symposium (SAS) 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/SAS58821.2023.10254018 (2023).

DecaWave. DWM1001 Product brief. Qorvo https://www.qorvo.com/products/d/da007951 (2017)

DecaWave. DWM1001 Product datasheet. Qorvo https://www.qorvo.com/products/d/da007952 (2017)

Marković, L., Kovač, M., Milijas, R., Car, M. & Bogdan, S. Error state extended Kalman filter multi-sensor fusion for unmanned aerial vehicle localization in GPS and magnetometer denied indoor environments. In 2022 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS) 184–190, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUAS54217.2022.9836124 (2022).

Dotlic, I., Connell, A. & McLaughlin, M. Ranging methods utilizing carrier frequency offset estimation. In 2018 15th Workshop on Positioning, Navigation and Communications (WPNC) 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/WPNC.2018.8555809 (2018).

DecaWave. APS014: DW1000 Antenna Delay Calibration. Qorvo https://www.qorvo.com/products/d/da008449 (2024).

DecaWave. DW1000 user manual. Qorvo https://www.qorvo.com/products/d/da007967 (2017).

Malajner, M., Planinšič, P. & Gleich, D. UWB ranging accuracy. In 2015 International Conference on Systems, Signals and Image Processing (IWSSIP) 61–64, https://doi.org/10.1109/IWSSIP.2015.7314177 (2015).

DecaWave. DWM1001C datasheet. Qorvo https://www.qorvo.com/products/d/da007950 (2017).

IEEE. IEEE standard for local and metropolitan area networks–Part 15.4: Low-rate wireless personal area networks (LR-WPANs). IEEE Std 802.15.4-2011 (Revision of IEEE Std. 802.15.4-2006) https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEESTD.2011.6012487 (2011).

Bosch. GLM 120 C Instruction Manual. Bosch Professional Power Tools & Accessories https://www.bosch-professional.com/binary/ocsmedia/optimized/full/o293625v21_160992A4F4_201810.pdf (2018).

Matsumoto, K. et al. Development of a tour guide and co-experience robot system using the quasi-zenith satellite system and the 5th-generation mobile communication system at a theme park. Robomech J. 8, 4, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40648-021-00192-7 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Towards robust and efficient device-free localization using UWB sensor network. Proc. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 41, 451–469, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmcj.2017.03.006 (2017).

Miraglia, G., Maleki, K. N. & Hook, L. R. Comparison of two sensor data fusion methods in a tightly coupled UWB/IMU 3-D localization system. In 2017 International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC) 611–618, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICE.2017.8279941 (2017).

Madyastha, V. et al. Extended Kalman filter vs. error state Kalman filter for aircraft attitude estimation. In AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2011-6615 (2011).

Feng, D., Wang, C., He, C., Zhuang, Y. & Xia, X.-G. Kalman-filter-based integration of IMU and UWB for high-accuracy indoor positioning and navigation. IEEE Internet of Things J. 7, 3133–3146, https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2020.2965115 (2020).

Snyder, J. P. Map projections: A working manual. Report No. 1395, https://doi.org/10.3133/pp1395 (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1987).

Wang, M., Chen, Z., Zhou, Z., Fu, J. & Qiu, H. Analysis of the applicability of dilution of precision in the base station configuration optimization of ultrawideband indoor TDOA positioning system. IEEE Access. 8, 225076–225087, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3045189 (2020).

Lee, B. Comprehensive UWB dataset. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29605775 (2025).

Di Pietra, V., Dabove, P. & Piras, M. Loosely coupled GNSS and UWB with INS integration for indoor/outdoor pedestrian navigation. Sensors 20, 6292, https://doi.org/10.3390/s20216292 (2020).

Shalihan, M., Liu, R. & Yuen, C. NLOS ranging mitigation with neural network model for UWB localization. In 2022 IEEE 18th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE) 1370–1376, https://doi.org/10.1109/CASE49997.2022.9926650 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. Ultra-wideband ranging error mitigation with novel channel impulse response feature parameters and two-step non-line-of-sight identification. Sensors 24, 1703, https://doi.org/10.3390/s24051703 (2024).

Xin, J., Gao, K., Shan, M., Yan, B. & Liu, D. A Bayesian filtering approach for error mitigation in ultra-wideband ranging. Sensors 19, 440, https://doi.org/10.3390/s19030440 (2019).

Barral, V., Suárez-Casal, P., Escudero, C. J. & García-Naya, J. A. Multi-sensor accurate forklift location and tracking simulation in industrial indoor environments. Electronics 8, 1152, https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8101152 (2019).

Oursland, J. & Mehrabian, M. An invariant extended Kalman filter for IMU-UWB sensor fusion. In 2024 33rd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN) 154–159, https://doi.org/10.1109/RO-MAN60168.2024.10731434 (2024).

Yao, L., Yao, L. & Wu, Y.-W. Analysis and improvement of indoor positioning accuracy for UWB sensors. Sensors 21, 5731, https://doi.org/10.3390/s21175731 (2021).

Zhao, W., Goudar, A. & Schoellig, A. P. Finding the right place: Sensor placement for UWB time difference of arrival localization in cluttered indoor environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 7, 6075–6082, https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2022.3165181 (2022).

Zhao, M. et al. ULoc: Low-Power, Scalable and cm-Accurate UWB-Tag Localization and Tracking for Indoor Applications. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 5, 140, https://doi.org/10.1145/3478124 (2021).

Yoo, S. M. & Park, C. An accurate indoor user position estimator for multiple anchor UWB localization. In 2020 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC) 1888–1890, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTC49870.2020.9289569 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Hyundai Motor Company ZERO1NE Incubation Team 'WhereB Project’ and the Ministry of the Interior and Safety (MOIS, Korea) (no. RS202400408982).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Byeong-Hyun Lee: Methodology, Formal analysis & investigation, Validation, and Writing—original draft preparation; Jeik Choi: Resources & Experiment; Siheon Jeong: Writing—review; Jung Hun Choi: Funding acquisition; Ki-yong Oh: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, and Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, B., Choi, J., Jeong, S. et al. Comprehensive outdoor UWB dataset: Static and dynamic measurements in LOS/NLOS environments. Sci Data 12, 1532 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05887-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05887-9