Abstract

Lithachne pauciflora is a herbaceous bamboo species characterized by its short height, low degree of lignification, and dimorphic florets, making it a special model for studying the key trait evolution in bamboo. Here, we assembled a high-quality, chromosome-level genome of L. pauciflora by integrating PacBio HiFi long reads, short reads, and Hi-C technology. The final genome assembly is 1.7 Gb with a scaffold N50 of 147.73 Mb. 99.3% of sequences were anchored onto 11 pseudo-chromosomes, with a BUSCO score of 98.6% and LAI value of 21. The total length of repeat elements is 1.43 Gb, accounting for 84.02% of the whole genome assembly. We annotated 32,696 protein-coding genes, of which 94.8% received functional annotations. This genome assembly of L. pauciflora provides valuable insights into chromosomal evolution and key trait evolution in herbaceous bamboo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Bamboo (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) comprises approximately 136 genera and 1,700 species in 19 subtribes1, is one of the most diverse lineages within the grass family. According to their degree of lignification, bamboo can be classified into woody and herbaceous lineages. Woody bamboo, representing over 90% of the bamboo diversity, is well-known for tall and highly lignified culms, making it a major component within forest ecosystems. Certain woody bamboo species, such as moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) are of great economic, ecological, and cultural value in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Previous studies have reported a total of 16 bamboo genomes representing different lineages and ploidal levels2,3,4,5,6,7,8. These include three herbaceous bamboos with HH genome (Olyra latifolia, Raddia guianensis, and Ra. distichophylla), four temperate woody bamboos with CCDD genome (Ampelocalamus luodianensis, Hsuehochloa calcarea, P. edulis, P. violascens ‘Prevernalis’), three neotropical woody bamboos with BBCC genome (Guadua angustifolia, Otatea glauca, Rhipidocladum racemiflorum), and five paleotropical woody bamboos with AABBCC genome (Bonia amplexicaulis, Dendrocalamus brandisii, D. latiflorus, D. sinicus, Melocanna baccifera). Additionally, the report of the nonaploid woody bamboo genome (Bambusa odashimae) represents the deciphering of the highest chromosome count9. Most of these studies focused on woody bamboo, suggesting that the allopolyploid evolutionary history and subgenome dominance may collectively contribute to the key innovations of woody bamboo7.

Herbaceous bamboos play a crucial role in bridging the gap between woody bamboos and other grasses, however, they have received far less attention. These bamboos are mainly found in the Neotropical Americas, Africa (including Madagascar), and New Guinea. They are characterized by their short height, low degree of lignification, unbranched culms typically lacking culm sheaths, unisexual spikelets, and dimorphic florets10. Lithachne pauciflora is the most widely distributed species within Lithachne genus, which typically grows to a height of less than 30 centimeters and thrives in shaded understory environments (Fig. 1a). The leaf bases are asymmetrical. The inflorescences are both terminal and axillary, with the terminal inflorescences generally bearing only male spikelets, while the inflorescences at the lower nodes contain a distal female spikelet and one or two male spikelets (Fig. 1b). Phylogenetic studies have shown that Lithachne is monophyletic and closely related to Olyra11. Species within this genus are diploid, with a chromosome number reported as 2n = 2x = 2212. It is suggested that the ancestral herbaceous bamboo karyotype (AGK-H) was 11, with a potential nested chromosome fusion (NCF) event involving chr10-chr12 leading to a reduction of the ancestral number from 12 to 117. However, since only chromosome-level genomes of two genera have been published, it remains to be settled whether this event occurs at the ancestor node of herbaceous bamboo or species-specific.

In this study, we generated a high-quality chromosome-level genome of L. pauciflora by integrating PacBio HiFi reads (94 Gb, 62×), short reads (106.9 Gb, 70×), and Hi-C data (278.5 Gb, 183×) (Table 1). The total length of primary assembled contigs is 1,707,736,184 bp, which is similar to the estimated genome size of flow cytometry and K-mer analyses. After scaffolding, the final genome assembly is 1,697,057,541 bp, with N50 of scaffolds of 147.73 Mb (Table 2). 99.3% of sequences were anchored onto 11 pseudo-chromosomes (Fig. 2a). Only four gaps were detected in the assembled genome. Telomeres were successfully identified at both ends of seven chromosomes, while one end of four chromosomes (Lpa01, Lpa04, Lpa05, and Lpa08). Additionally, putative centromere regions were identified for all chromosomes (Fig. 3). A total of 1,409,694 repeat elements with a length of 1,434,842,875 bp were identified, accounting for 84.02% of the whole genome assembly (Table 3). We annotated 32,696 protein-coding genes, with an average gene length of 3,763 bp (Table 4). The genome of L. pauciflora generated here provides valuable insights for studying the chromosomal evolution and key trait evolution in herbaceous bamboo.

Genome features of L. pauciflora. (a) Hi-C interaction heatmap of the L. pauciflora genome, with chromosomes labeled according to their collinearity with the rice genome. (b) Circos plot of the L. pauciflora genome. The tracks arranged from outermost to innermost are as follows: (a) 11 pseudo-chromosomes with filled regions indicating syntenic blocks with rice chromosomes, (b) GC contents, (c) LTR density, (d) TIR density, (e) repeat density, (f) gene density, and (g) syntenic blocks of rice genome compared to the L. pauciflora genome.

Methods

Plant materials and sequencing

Fresh young leaves were collected from a single plant of L. pauciflora cultivated at the greenhouse of Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. High-quality genomic DNA was extracted following the standard operating procedure of the modified Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) method13. Tissues of the vegetative leaf blade, female spikelet, and male spikelet, were sampled during the same time of day and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction and transcriptome sequencing.

The short-read library was prepared with a DNA-fragment insert size of 400 bp, and paired-end reads were generated using the DNBSEQ-T7 platform (BGI lnc., Shenzhen, China) with 70× sequencing depth (Table 1). The Pacbio Template Prep Kit 1.0 library preparation protocol was used for Long-read library preparation. High fidelity reads sequencing was performed using the PacBio Revio sequencing platform in the CCS mode, with a total of 94 Gb (62× sequencing depth) HiFi data with N50 sizes of 18.6 kb (Table 1). Hi-C libraries were prepared based on the standard library construction process of Illumina’s TruSeq DNA PCR-free prep kit reagents by the Personalbio Technology Company (Shanghai, China). Generally, fresh young leaves of L. pauciflora were first fixed in 2% formaldehyde solution, and then homogenized and centrifuged to isolate the nuclei. The cross-linked chromatin was then digested using the restriction enzyme MboI. Biotin-labeled adapters were subsequently used to fill in both sticky ends of the digested fragments. Ligation was performed using T4 DNA ligase, followed by further enrichment, purification, and trimming of the fragments to a size range of 300–700 bp. These Hi-C libraries were sequenced on the Illumina Novaseq platform to produce 150 bp paired-end reads with total data of 278.5 Gb (183× sequencing depth). Three different tissues were sampled for the transcriptome data sequencing. Each tissue was sequenced with three replicates, except for female and male spikelets that sequenced only twice due to material limitations. The DNBSEQ-T7 sequencing platform was used for 2 × 150 bp data sequencing. The sequencing library fragment size was 380 bp, and 6 Gb data was generated for each sample.

Genome size estimation

Both flow cytometry and k-mer frequency analyses were adopted to estimate the genome size of L. pauciflora. For the flow cytometry analysis, the genome size was determined using the BD FACScalibur flow cytometer following the standard procedure14,15 with the model plant tomato as reference. For the k-mer frequency analysis, we first used fastp v0.23.116 to perform quality control on the short-read sequencing data. Next, we used Jellyfish v2.2.1017 to count k-mers on the filtered data and GenomeScope v1.0.018 to evaluate the genome size and heterozygosity. The estimated genome size was about 1.5 Gb, with a heterozygosity of 0.33% (Table 1).

Chromosome-level genome assembly and quality evaluation

Fastp v0.23.116 was used to evaluate the sequencing error rate and perform quality control on the Hi-C data. Subsequently, the clean HiFi reads were de novo assembled using the default parameters of the Hifiasm v0.19.919 software to obtain the preliminary assembled genome contig sequence. The primary assembly contained 1,707.73 Mb in 460 contigs with a contig N50 of 140.57 Mb (Table 2). To generate a contact map, Juicer v2.20.0020 was then used to align the Hi-C data to the preliminary assembled genome sequence. 3D-DNA v18011421 was used to sort and orient the contigs according to the strength of the Hi-C reads interaction relationship, and Hi-C-assisted chromosome assembly was performed. Juicebox v1.11.0822 was then used to manually check and adjust the preliminary chromosome assembly results, mainly for chromosome boundaries, incorrect insertions, and directions. 3D-DNA was then used to generate the adjusted chromosome sequence, and the final genome assembly consisted of 11 chromosome sequences (Fig. 2, Table 2). PMAT v2.0.123 was utilized to assemble the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes, and the relevant contigs were excluded from the genome assembly.

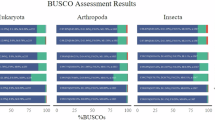

We evaluate the quality of the chromosome-level genome sequence based on contiguity, correctness, and completeness. First, BWA v0.7.1724 was used to map the short paired-end reads back to the genome sequences, and the reads mapping rate was 98.65% (Table 2). Subsequently, BUSCO v5.5.0 (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs)25 was used to identify single-copy homologous genes in the OrthoDB database embryophyta_odb10, and the completeness of the assembled genome is evaluated as 98.6% with 95.8% complete single-copy BUSCOs (Table 2). Next, the LTR Assembly Index (LAI)26 was used to assess the continuity of the genome assembly based on the repetitive elements prediction results by EDTA v2.2.027 and LTR_retriever28 software. According to the standard of draft level (0 ≤ LAI < 10), reference level (10 ≤ LAI < 20), and gold level (20 ≤ LAI), the LAI value 21 suggests high quality of the assembly of L. pauciflora.

Repetitive elements annotation and telomere prediction

EDTA v2.2.027 was adopted to annotate the transposable elements (TE) in the genome of L. pauciflora with default parameters. As a result, a total of 1,409,694 TE sequences with a total length of 1.43 Gb, accounting for 84.02% of the whole genome was identified. Of which, the long terminal repeats (LTRs, 68.68%) comprise the highest proportion, followed by terminal inverted repeats (TIRs, 8%) (Table 3). For telomere prediction, we utilized the TeloExplorer module of quarTeT v1.2.529, employing the canonical plant telomeric repeat sequence TTTAGGG as the search motif. We successfully predicted telomeric sequences for all 11 chromosomes. Among these, seven chromosomes (Lpa02, Lpa03, Lpa06, Lpa07, Lpa09, Lpa10, and Lpa11) exhibited telomeric repeats at both ends, while four chromosomes (Lpa01, Lpa04, Lpa05, and Lpa08) showed repeats at only one end (Fig. 3). To identify centromeres, we used the CentroMiner module of quarTeT29, with inputs from the repetitive element annotation generated by EDTA v2.2.027 and our gene annotation file that includes information on alternative splicing. The results indicated that each chromosome contains a distinct region enriched with tandem repeats, likely representing the putative centromere.

Gene prediction and annotation

Protein-coding genes were annotated by integrating approaches including ab initio prediction, transcriptome-based, and homology-based strategy. Gene structure annotation was performed using a soft-masked genome sequence generated by EDTA v2.0.027. We utilized BRAKER3 v3.0.330 in ETP mode to integrate evidence from ab initio prediction, RNA-seq data, and protein homology. RNA-seq reads were aligned to the genome using HISAT2 v2.2.131, and StringTie2 v2.2.132 was employed to assemble transcript models. GeneMark-ETP33 was trained and executed using both the RNA-seq alignments and protein evidence from the OrthoDB database, incorporating protein annotations from Olyra latifolia (GCA_036346145.1) and Raddia guianensis (GCA_036346415.1). Subsequently, AUGUSTUS v3.5.034 was trained and executed ab initio gene prediction guided by the same extrinsic evidence along with the output from GeneMark-ETP33. TSEBRA35 was then used to integrate the predictions from AUGUSTUS v3.5.034 and GeneMark-ETP33, producing the final set of gene models. To enhance the quality of the annotations and recover untranslated regions (UTRs), Trinity v2.8.536 was used to perform de novo transcriptome assembly, and the resulting transcripts were further processed with PASA v2.5.337 to polish and refine the BRAKER3-derived gene models. Following the guidelines of Vuruputoor et al.38, we excluded mono-exonic genes that lacked functional annotations based on evidence from domain or sequence similarity (see the section on Functional Prediction for details). This process led to our final gene annotation.

Overall, 32,696 protein-coding genes were annotated for the L. pauciflora genome (Table 4), which is slightly higher than the counts of 31,189 in Ol. latifolia and 27,496 in Ra. guianensis7. The gene length ranges from 98 bp to 347,248 bp, with an average gene length of 3,763 bp and a median of 2,288 bp. The average length of coding sequences (CDS) is 1,100 bp and a median of 882 bp. In addition, each gene has an average of 4 exons, with an average length of 654 bp.

Functional prediction

Three strategies were adopted for the functional prediction of protein-coding genes. GFAP v3.139 was used to align predicted genes with the GO, KEGG, and Pfam databases, with default values. DIAMOND v2.1.940 (-evalue 1e-5, -max-target-seqs. 5, Identity > 30%) and BLAST v2.15.041 (-evalue 1e-5, -max_target_seqs. 5, -qcov_hsp_perc 30) were used to identify the best match by aligning the protein sequences to the SwissProt and NR databases, respectively. Finally, 31,000 genes were functionally annotated in at least one of the above databases, accounting for 94.8% of the predicted protein-coding genes (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Table S1).

Statistical Venn diagrams (a) of L. pauciflora genome and (b) syntenic relationships of chromosomes 10 and 12 between herbaceous bamboo and the rice genome. The Venn diagrams illustrate the functional annotations of protein-coding genes from L. pauciflora against the five public databases. The diagrams illustrate the protein-coding genes categorized by different functional annotations, displaying the shared core genes (center), overlapping genes (overlapping regions), and specific genes (outer regions) for each functional annotation. The macrosyntenic relationships of chromosomes 10 and 12 between herbaceous bamboo and rice genomes are presented, along with the nested chromosome fusion (NCF) shared by three herbaceous bamboos.

Annotation of noncoding RNAs

The tRNAscan-SE v2.0.1242 was used to identify the transfer RNAs (tRNAs). RNAmmer v1.243 was adopted to annotate ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs). Other noncoding RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs) and small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), were identified using Infernal v1.1544 by searching against the Pfam database. In total, 2,415 tRNAs, 5,386 rRNAs, 801 miRNAs, and 2,764 snRNAs were predicted in L. pauciflora genome (Table 5; Supplementary Table S2).

Syntenic analysis

The syntenic analysis among the genomes of L. pauciflora, Ol. latifolia, and Ra. guianensis, with the rice genome serving as a reference, was performed using the jcvi.compara.catalog ortholog pipeline from jcvi v1.1.1745. Syntenic blocks were identified with the following parameters: a C-score cutoff of 0.7, a search extent of 20 for flanking regions, and a minimum of 4 anchor pairs required to define a block. The clear overall 1:1 collinearity between the L. pauciflora genome and rice was observed (Fig. 2b), thus we named the chromosomes of L. pauciflora according to their collinearity with the rice genome. Previous research suggested that a nested chromosome fusion (NCF) involving chromosomes 12 and 10 of the rice genome occurred in the ancestral herbaceous bamboo karyotype, leading to a reduction in chromosome number from 12 to 117. Our study further solidified this finding by revealing a shared NCF event observed in the L. pauciflora genome (Fig. 4b).

Data Records

The relevant data generated in this paper have been uploaded in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC), Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences/China National Center for Bioinformation, under the BioProject accession number PRJCA036467. BGI short-reads, PacBio HiFi long-reads, Hi-C reads, and RNA-seq data have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) in NGDC under the accession number CRA02340146, CRA02342947, CRA02343748, and CRA02341549. The genome assembly file has been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession number JBPVWQ00000000050. Additionally, the genome assembly and annotation data have been deposited in Figshare51.

Technical Validation

Evaluation of the genome assembly and annotation

In this study, a total of 62 × HiFi reads, 70× short reads, and 183× Hi-C data (Table 1) were generated to achieve a high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly of L. pauciflora. The high correctness, contiguity, and completeness of the assembly were supported by various lines of evidence. Firstly, 98.65% of the short reads were properly mapped back to the assembled genome sequences, suggesting the correctness of the L. pauciflora genome assembly (Table 2). The Hi-C heatmap displayed strong interaction signals across the 11 chromosomes (Fig. 2), revealing a well-executed chromosome scaffolding process with no obvious errors. Moreover, the N50 of the scaffolds in the L. pauciflora assembly reached 147.7 Mb, surpassing the chromosome-level assemblies of Ol. latifolia (57.04 Mb) and Ra. guianensis (56.58 Mb)7. Subsequently, BUSCO analysis revealed that the proportion of complete genes (including both single-copy and duplicated genes) was 98.6%, with only 0.9% of gene missing, highlighting the high level of completeness of the assembled genome. Additionally, the LTR Assembly Index (LAI)26 was calculated to assess the continuity of the genome assembly. Based on the classifications of draft level (0 ≤ LAI < 10), reference level (10 ≤ LAI < 20), and gold level (20 ≤ LAI), the LAI value of 21 suggests a high-quality assembly of L. pauciflora.

We identified only four gaps in the assembled genome, which are located on chromosomes Lpa06 (one gap), Lpa07 (one gap), and Lpa09 (two gaps) (Fig. 3). We successfully predicted telomeric sequences for all 11 chromosomes. Among these, seven chromosomes (Lpa02, Lpa03, Lpa06, Lpa07, Lpa09, Lpa10, and Lpa11) exhibited telomeric repeats at both ends, while four chromosomes (Lpa01, Lpa04, Lpa05, and Lpa08) showed telomeres at only one end. The results of centromere prediction indicated that each chromosome contains a distinct region enriched with tandem repeats, likely marking the location of the putative centromere. In summary, these evaluation demonstrates a high quality of our genome assembly.

The predicted number of coding genes, totaling 32,696, which is slightly higher than the counts of Ol. latifolia (31,189) and Ra. guianensis (27,496)7. The quality of the gene annotation was evaluated using BUSCO v5.5.025 with the embryophyta_odb10 database. The results indicate that our annotation is of high quality38, with 95.4% complete BUSCOs, including 92.8% complete and single-copy BUSCOs, 2.6% complete and duplicated BUSCOs, 2.5% fragmented BUSCOs, and 2.1% missing BUSCOs. The proportion of single-exon genes was 0.36. To further assess the completeness and accuracy of the annotated gene sets, the predicted coding genes were functionally annotated through BLAST searches against multiple databases, including NR, SwissProt, KEGG, GO, and Pfam. The results indicated that 94.8% (31,000) of the predicted gene models were functionally annotated in at least one of these databases (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table S1).

Data availability

All sequencing and assembly data generated in this study have been deposited in public repositories. Raw sequencing data including BGI short-reads, PacBio HiFi long-reads, Hi-C reads, and RNA-seq data are available in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) at the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) under the BioProject accession number PRJCA036467, with the following accession numbers: CRA02340146, CRA02342947, CRA02343748, and CRA02341549. The genome assembly has been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession number JBPVWQ00000000050. Additionally, the genome assembly and annotation files are also deposited in Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29608349.v2)51.

Code availability

In this study, no custom code was developed. All data processing commands and pipelines were executed following the manuals and protocols provided by the published bioinformatics software. Details regarding the specific software versions and parameters utilized can be found in the Methods section.

References

Soreng, R. J. et al. A worldwide phylogenetic classification of the Poaceae (Gramineae) III: An update. J. Syst. Evol. 60, 476–521, https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12847 (2022).

Peng, Z. et al. The draft genome of the fast-growing non-timber forest species moso bamboo (Phyllostachys heterocycla). Nat. Genet. 45, 456–461, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2569 (2013).

Zhao, H. et al. Chromosome-level reference genome and alternative splicing atlas of moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). GigaScience 7, giy115, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giy115 (2018).

Guo, Z.-H. et al. Genome sequences provide insights into the reticulate origin and unique traits of woody bamboos. Mol. Plant 12, 1353–1365, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2019.05.009 (2019).

Li, W. et al. Draft genome of the herbaceous bamboo Raddia distichophylla. G3-Genes Genom. Genet. 11, jkaa049, https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkaa049 (2021).

Zheng, Y. et al. Allele-aware chromosome-scale assembly of the allopolyploid genome of hexaploid Ma bamboo (Dendrocalamus latiflorus Munro). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 64, 649–670, https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.13217 (2022).

Ma, P.-F. et al. Genome assemblies of 11 bamboo species highlight diversification induced by dynamic subgenome dominance. Nat. Genet. 56, 710–720, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-024-01683-0 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of Phyllostachys violascens ‘Prevernalis’. Sci. Data 12, 912, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04556-1 (2025).

Wang, Y.-J. et al. Haplotype-resolved nonaploid genome provides insights into in vitro flowering in bamboos. Hortic. Res. 11, uhae250, https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhae250 (2024).

Bamboo Phylogeny Group. An updated tribal and subtribal classification of the bamboos (Poaceae: Bambusoideae). J. Amer. Bamboo Soc. 21, 1–10 (2012).

Oliveira, R. P. et al. A molecular phylogeny of Raddia and its allies within the tribe Olyreae (Poaceae, Bambusoideae) based on noncoding plastid and nuclear spacers. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 78, 105–117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.04.012 (2014).

Kellogg, E. A. In The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. XIII Flowering Plants. Monocots: Poaceae (ed. Kubitzki, K.) (Springer, 2015).

Doyle, J. & Doyle, J. L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19, 11–15 (1987).

Doležel, J. & Bartoš, J. A. N. Plant DNA flow cytometry and estimation of nuclear genome size. Ann. Bot. 95, 99–110, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mci005 (2005).

Doležel, J., Greilhuber, J. & Suda, J. Estimation of nuclear DNA content in plants using flow cytometry. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2233–2244, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2007.310 (2007).

Chen, S. Ultrafast one-pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using fastp. iMeta 2, e107, https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.107 (2023).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 (2011).

Vurture, G. W. et al. GenomeScope: fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics 33, 2202–2204, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btx153 (2017).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal3327 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012 (2016).

Bi, C. et al. PMAT: an efficient plant mitogenome assembly toolkit using low-coverage HiFi sequencing data. Hortic. Res. 11, uhae023, https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhae023 (2024).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv, 1303.3997v1302 [q-bio.GN] (2013).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simão, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4647–4654, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab199 (2021).

Ou, S., Chen, J. & Jiang, N. Assessing genome assembly quality using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI). Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e126, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky730 (2018).

Ou, S. et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol. 20, 275, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1905-y (2019).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: A Highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.01310 (2018).

Lin, Y. et al. quarTeT: a telomere-to-telomere toolkit for gap-free genome assembly and centromeric repeat identification. Hortic. Res. 10, uhad127, https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhad127 (2023).

Gabriel, L. et al. BRAKER3: Fully automated genome annotation using RNA-seq and protein evidence with GeneMark-ETP, AUGUSTUS, and TSEBRA. Genome Res. 34, 769–777 (2024).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Shumate, A., Wong, B., Pertea, G. & Pertea, M. Improved transcriptome assembly using a hybrid of long and short reads with StringTie. PLoS Comp. Biol. 18, e1009730, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009730 (2022).

Brůna, T., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. GeneMark-ETP significantly improves the accuracy of automatic annotation of large eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 34, 757–768 (2024).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W435–W439, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl200 (2006).

Gabriel, L., Hoff, K. J., Brůna, T., Borodovsky, M. & Stanke, M. TSEBRA: transcript selector for BRAKER. BMC Bioinform. 22, 566, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-021-04482-0 (2021).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494–1512, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.084 (2013).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 9, R7, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7 (2008).

Vuruputoor, V. S. et al. Welcome to the big leaves: Best practices for improving genome annotation in non-model plant genomes. Appl. Plant Sci. 11, e11533, https://doi.org/10.1002/aps3.11533 (2023).

Xu, D. et al. GFAP: ultrafast and accurate gene functional annotation software for plants. Plant Physiol. 193, 1745–1748, https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiad393 (2023).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H.-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 18, 366–368, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01101-x (2021).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinf. 10, 421, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 (2009).

Chan, P. P., Lin, B. Y., Mak, A. J. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 9077–9096, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab688 (2021).

Lagesen, K. et al. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 3100–3108, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm160 (2007).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509 (2013).

Tang, H. et al. JCVI: A versatile toolkit for comparative genomics analysis. iMeta 3, e211, https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.211 (2024).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/search?searchTerm=CRA023401 (2025).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/search?searchTerm=CRA023429 (2025).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/search?searchTerm=CRA023437 (2025).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/search?searchTerm=CRA023415 (2025).

Qian, K.-C., Liu, J.-F., Yang, Y., Guo, C. & Guo, Z.-H. A high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly of herbaceous bamboo species Lithachne pauciflora, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBPVWQ000000000 (2025).

Qian, K.-C., Liu, J.-F., Yang, Y., Guo, C. & Guo, Z.-H. A high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly of herbaceous bamboo species Lithachne pauciflora. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29608349.v2 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Dieter Ohrnberger (Baan Sammi Nature Resort & Bamboo Garden, Thailand), Jing-Xia Liu, Meng-Yuan Zhou, and Ling Mao (all Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences unless specified) for help in samples collection. Dr. Yu-Xing Xu, Zhong-Xiang Su, and Zuo-Ying Xiahou for inspiring discussion and technical support. This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200193), the Fund of Yunnan Key Laboratory of Crop Wild Relatives Omics (CWR-2024-02), the Fund of Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202201AT070135), and facilitated by the iFlora High Performance Computing Center of Germplasm Bank of Wild Species, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhen-Hua Guo and Cen Guo conceived and designed the research, Cen Guo, Ke-Cheng Qian, and Yang Yang prepared plant samples. Ke-Cheng Qian, Cen Guo, and Jun-Feng Liu performed data analysis. Ke-Cheng Qian, Cen Guo, and Zhen-Hua Guo drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qian, KC., Liu, JF., Yang, Y. et al. A high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly of herbaceous bamboo species Lithachne pauciflora. Sci Data 12, 1736 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06024-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06024-2