Abstract

The parrotfish, Scarus rivulatus, is a widely distributed herbivorous species, that helps maintain reef resilience by controlling algal growth. However, overfishing and reef degradation threaten its populations, and the lack of genomic resources limits studies on its adaptive potential and conservation strategies. In this study, we successfully assembled a high-quality chromosome-level genome for S. rivulatus using a combination of Illumina, Nanopore, and Hi-C technologies. The assembled genome is 1.58 Gb in size, with scaffold N50 lengths reaching 67.2 Mb. Hi-C contact maps anchored approximately 96.2% of the assembled sequences onto 24 chromosomes. Repetitive sequences accounted for 48.84% of the genome. The BUSCO assessment revealed that 97.8% of the expected conserved genes were complete. Integrating three lines of evidence, we predicted 41,823 protein-coding genes, of which 73.91% were functionally annotated in at least one protein database. This chromosome-level genome assembly filled a critical gap in genomic resources for S. rivulatus, providing a valuable foundation for elucidating its adaptive mechanisms in response to coral reef degradation and facilitating genetic breeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Coral reefs are among the most biologically diverse and productive marine ecosystems in the world, providing an ideal habitat for marine life1. As key consumers, coral reef fishes play a crucial role in cycling carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P), as well as in processes such as biomass production, herbivory, and piscivory (secondary consumption)2. These functions are intrinsically linked, with the synergistic actions of reef fishes collectively enhancing ecosystem resilience and supporting the maintenance of ecological balance. However, due to the combined effects of marine heatwaves, ocean acidification, pollution, and overfishing, global coral reef coverage has declined significantly in recent decades3,4. The degradation of coral reefs has led to the decrease of coral fish biomass and the change of community structure5. For instance, in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, a massive coral bleaching event in 2016 led to the widespread death of about 30% of coral communities and a continuing decline in local fish species richness6. Recent studies have demonstrated that the spatial covariation patterns of herbivore functional roles can significantly affect coral reef resilience. Following coral mortality events, browsers, in contrast to grazers, play a more critical role in removing established macroalgae from reef substrates7. As the transition of corals to macroalgae gradually becomes the norm, herbivorous coralfish have received increasing attention for their role in regulating competition between corals and algae8.

Herbivorous fishes are considered key contributors to maintaining coral reef health, as they regulate the competition between algae and scleractinian corals for substrate space by controlling benthic algae, thereby enhancing reef resilience and preventing phase shifts9,10,11. Among them, Acanthuridae and Scaridae are prominent herbivores in coral reef ecosystems12. Acanthurus nigrofuscus is recognized for its broad dietary range, which enables it to thrive under various environmental conditions, including degraded coral reefs13. In contrast, Ctenochaetus striatus primarily feeds on detritus; however, the accumulation of fine sediments can inhibit its feeding efficiency, thereby diminishing its critical role in sediment removal and redistribution within coral reef ecosystems14,15. Species such as S. rivulatus and S. taeniopterus exhibit a preference for feeding on crustose coralline algae and the epilithic algal matrix associated with these substrates. This feeding behavior effectively suppresses the accumulation of tall filamentous and late-successional macroalgae, maintaining early-stage algal communities dominated by short filamentous algae and crustose coralline algae, which do not inhibit coral growth16,17. The study found that the growth rate of Caribbean coral reefs declined in both prehistoric and historical periods as parrotfish declined18. Thus, parrotfish play a critical role in maintaining coral-dominated reef habitats, and there is an urgent need to restore parrotfish populations for reef persistence.

The Scaridae family comprises 10 genera and 90 recognized species, with the genus Scarus emerging as the largest and most diverse, accounting for about 50 of these species19. Parrotfishes of the genus Scarus are primarily scrapers due to their special mouth structure, the fused dentate plate. Their beaks are strong and effective enough to grind up hard corals and rocks20. Among them, S. rivulatus is a widely distributed species in Indo-Pacific coral reefs, recognized for its crucial ecological functions and increasing commercial exploitation21. Due to rising demand for fisheries and the aquarium trade, populations of S. rivulatus are facing mounting pressure from overfishing, which could compromise their ecological role in reef systems22. Despite its ecological and economic importance, genetic and genomic resources for S. rivulatus remain limited, constraining our understanding of its adaptive capacity in the face of ongoing coral reef decline.

In recent years, genomics has become an increasingly important tool in conservation biology for understanding the genetic diversity of threatened species. For economically significant species, high-quality reference genomes are essential foundational genetic resources, which also hold considerable value for applications in aquaculture. In this study, we constructed a high-quality, chromosome-level genome assembly of S. rivulatus by integrating Illumina short-read sequencing, Nanopore long-read sequencing, and high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technology. The final assembly consisted of 24 chromosomes, with a total length of 1.58 Gb and a scaffold N50 of 67.2 Mb. We annotated 41,823 protein-coding genes, of which 73.91% (30,910 genes) were functionally annotated. Repetitive elements accounted for 48.84% of the genome, with DNA and LTR elements being particularly abundant. This reference genome fills an important gap in S. rivulatus genomic resources, providing a fundamental basis for exploring the genetic mechanisms underlying the adaptation of parrotfish to current reef degradation and supporting the conservation and restoration of both parrotfish populations and coral reef ecosystems.

Methods

Sample collection and DNA extraction

A single adult female S. rivulatus specimen was collected from Xincun Harbor, Hainan Province, China, in May 2019. Muscle tissue was excised and immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at –80 °C. High-quality genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from freshly harvested muscle using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol23. The integrity of the DNA was verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and DNA concentrations were quantified using the Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Short-read library construction and sequencing

According to the method described previously24, gDNA was sheared to an average fragment size of 300–500 bp using a Covaris 2000 Ultrasonicator (Covaris, USA) for short-read sequencing. Fragmented DNA was size-selected, end-repaired, and PCR-amplified to produce sequencing libraries. The prepared libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) in paired-end mode (150 bp), generating approximately 96 Gb of raw data.

Long-read library construction and sequencing

For long-read sequencing, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA was size-selected (~20 kb) using the BluePippin system (Sage Science, USA). Library preparation followed the 1D Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK109) protocol (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK). The final library concentration was measured using a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sequencing was carried out on a single flow cell of the PromethION platform (Oxford Nanopore Technologies), yielding approximately 196 Gb of raw data.

Hi-C library construction and sequencing

A Hi-C library was also prepared from the same genomic DNA sample to enable chromosome-level scaffolding. Following a previously described standard protocol with specific modifications25, we digested the DNA with MboI and enriched the resulting biotin-labeled Hi-C fragments using streptavidin C1 magnetic beads. Subsequent library preparation involved adding A-tails to the fragment ends and ligating them with Illumina PE sequencing adapters. The final libraries were amplified by PCR and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten to generate 150 bp paired-end reads. In total, 63 Gb of Hi-C sequencing data were obtained.

RNA library construction and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from ten tissues (fins, gonads, heart, intestines, blood, liver, muscles, brain, spleen, and kidneys) and treated with DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) to remove any genomic DNA contamination24. The integrity of the RNA from each tissue was verified using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). RNA-sequencing libraries with a 300 bp insert size were constructed for each sample, and sequencing was carried out on the Illumina HiSeq platform using 150 bp PE mode. The result was 90 Gb of raw data.

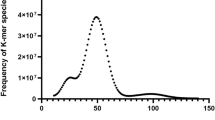

Sequencing data processing and genome survey

The Illumina short-read data were first assessed for quality using FastQC (v0.11.9)26, and low-quality reads and adapters were removed with SOAPnuke (v2.X)27. After filtering, the clean reads were used for genome size and heterozygosity estimation for S. rivulatus. K-mer frequency analysis was conducted with GCE (v1.0.2)28 using a k-mer size of 17. The resulting k-mer frequency distribution (Fig. 1) showed a major peak at a depth of 80. After excluding low-frequency k-mers, the genome size was estimated using the formula: genome size = total k-mer count/peak depth. The final estimated genome size was 1.55 Gb, with a heterozygosity rate of 0.77%.

De novo genome assembly

For S. rivulatus, de novo genome assembly was performed using Nanopore long-read data together with Illumina short reads. First, the assembly process using Nanopore data was carried out with NextDenovo (v2.5.0) (https://github.com/Nextomics/NextDenovo) under default parameters to generate an initial assembly. Then, to further improve the base-level accuracy, the assembly was polished using NextPolish (v1.4.1)29 by the Illumina data. The final contig-level assembly comprised 495 contigs, with a total length of 1.71 Gb, an N50 of 18.5 Mb, and a GC content of 39.36%. The longest contig reached 60.9 Mb (Table 1).

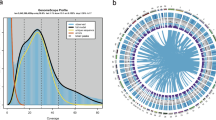

The Hi-C sequencing data were utilized to achieve the chromosome-level assembly of the S. rivulatus genome. Initially, low-quality and duplicate Hi-C raw reads were removed using Trimmomatic (v0.39)30. The resulting high-quality reads were aligned to the reference genome with Juicer (v1.6)31. Chromosome-level scaffolds were then generated by leveraging the genomic proximity information captured by the Hi-C data. To further scaffold the genome, the 3D-DNA32 pipeline was employed, followed by manual refinement of misassemblies using Juicebox (v1.11.08)33. The final chromosome-level assembly reached a total size of 1.58 Gb, with a scaffold N50 of 67.17 Mb (Table 1). It comprised 24 chromosomes (Fig. 2), ranging from 36.08 Mb to 81.71 Mb in length, with an average chromosome size of 66.02 Mb (Table 2). The GC content of the final assembly was 39.31%. Notably, the total assembled genome size closely matched the estimated genome size from the genome survey, reflecting the high integrity and completeness of this assembly.

Assembly results of the S. rivulatus genome. (A) Heat map of interactive intensity between chromosome sequences anchored by Hi-C. The width of each column reflects the relative length of the corresponding chromosome, while the intensity of the red color indicates the contact density. (B) Circos plot of the genome features. From the outermost to the innermost rings: (a) chromosomes, (b) GC content, (c) repeat content, and (d) gene density. The chromosome lengths were calculated, and the corresponding positions and lengths were used to create the outermost ring in the Circos plot. GC content was estimated by dividing the genome into 100 KB windows and calculating the GC ratio within each window, with the distribution of GC content displayed in the second ring. Repeat content was estimated by calculating the overlap between each window and known repetitive regions, represented in the third ring of the Circos plot. Gene density was estimated by counting the number of genes within each window and is shown in the innermost ring, reflecting the distribution of genes across the genome.

Repetitive sequences annotation

Prior to annotating protein-coding genes, repetitive regions in the genome were masked using a combined approach of De Novo and homology-based methods. We constructed an S. rivulatus specific repeat library using RepeatModeler (v2.0.3)34. Initially, this library contained 3,173 consensus sequences, among which 2,510 were categorized as unknown transposable element (TE) families. These unknown sequences were subsequently classified using DeepTE35, resulting in a reduction to 566 consensus sequences.

With this refined consensus sequence library, we annotated repetitive regions in the S. rivulatus genome using RepeatMasker (v4.1.2)36. This approach revealed that 48.84% of the genome consists of TE. The most prevalent DNA transposon family was hobo-Activator comprising 8.09% of the genome, followed by the Tc1 family (7.77%). The Gypsy/DIRS1 retrotransposons accounted for 7.41% of LTR (Table 3). Overall, S. rivulatus possesses a notably high proportion of TE.

Additionally, we calculated the Kimura two-parameter divergence (K divergence) using the calcDivergenceFromAlign.pl script from RepeatMasker (v4.1.2). The insertion time for each consensus sequence was estimated using the formula T = K/2r, where K denotes the divergence calculated by the script, and r represents the neutral mutation rate for teleost (2.5 × 10−⁹ substitutions/site/year). Our findings indicated that although S. rivulatus has a high overall TE content, most of these transposable elements underwent significant expansions approximately 10 million years ago (Mya) (Fig. 3A). Currently, active TE expansions appear to be limited.

Gene prediction and functional annotation

A repeat sequence library was built using RepeatModeler (v2.0.3) and applied with RepeatMasker (v4.1.2) to identify repetitive elements in the S. rivulatus genome. Redundant and overlapping sequences were removed to improve accuracy. The resulting masked genome was used for subsequent gene annotation.

To comprehensively predict protein-coding genes in the assembled genome, three complementary strategies were employed. First, de novo gene prediction was conducted using the self-training mode of Augustus (v3.4.0)37, with subsequent annotation refinement performed via the SNAP_to_GFF3.pl and augustus_GTF_to_EVM_GFF3.pl scripts from the Evidence Modeler (v1.1.1)38. Second, transcriptome-based prediction involved aligning RNA-seq data to the S. rivulatus genome and assembling the transcriptome using HISAT2 (v2.1.0)39 and StringTie (v2.1.4)40. Subsequently, TransDecoder (v5.7.0, https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder) was used to predict the open reading frames (ORFs). Third, homology-based predictions were carried out by aligning protein sequences from Labrus bergylta, Cheilinus undulatus, Notolabrus celidotus, Sparus aurata, and Acanthopagrus latus, which were downloaded from the NCBI database (Table 4), to the S. rivulatus genome. These alignments were further analyzed using Genewise41 to precisely determine exon-intron structures. Finally, the gene predictions from all three strategies were integrated using EVM to generate a high-confidence, consensus set of protein-coding genes.

Functional annotation of the predicted protein-coding genes in the S. rivulatus genome was conducted by aligning these sequences to commonly used protein databases, including SWISS-PROT, NR, TrEMBL, COG, and KEGG, using BLAST (blastp) with an e-value cutoff of 1e-5. Motifs and domains were further annotated using InterProScan (v4.8)42, and partial non-coding RNAs were identified with Infernal (v1.1.2)43.

A total of 41,823 protein-coding genes were predicted in the S. rivulatus genome, among which 30,910 genes (73.91%) were functionally annotated in at least one of the utilized databases (Table 5). Specifically, 30,567 genes (73.09%) were annotated in the NR database, 30,557 genes (73.06%) in TrEMBL, 23,536 genes (56.28%) in SwissProt, 25,970 genes (62.10%) in KEGG, and 8,474 genes (20.26%) in COG (Fig. 3B). In addition to protein-coding genes, non-coding RNAs were comprehensively identified, including 1,794 tRNAs, 284 rRNAs, 543 snRNAs, and 338 miRNAs (Table 6).

Data Records

The sequencing data and genome assembly have been submitted to the public databases. The Illumina short-read sequencing, Nanopore long-read sequencing, Hi-C sequencing, and RNA-seq data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the accession number SRP60003344. The genome assembly has been deposited at the NCBI GenBank under the accession GCA_051912175.145. Moreover, data of the genome annotations, predicted coding sequences, and protein sequences have been deposited at Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29642444.v1)46.

Technical Validation

Evaluation of the genome assembly

To assess the integrity and quality of the genome assembly, we used BUSCO (v5.4.4)47 software and performed analyses based on the Actinopterygii database, which contains 3,640 conserved single-copy orthologs. The results showed that a total of 3,573 (98.16%) complete BUSCO genes were detected, including 3,455 complete single-copy genes and 118 complete duplicated genes. In addition, 21 (0.58%) fragmented genes were detected and only 46 (1.26%) missing genes (Table 7). Additionally, to evaluate the accuracy of our assembly, we aligned Illumina short reads to the assembled genome using BWA (v0.7.17)48 and performed statistical analysis using SAMtools (v1.13)49. The results showed that 99.66% of the short reads were successfully aligned, and 96.48% of them were correctly aligned, indicating that the assembly had high alignment consistency and accuracy. These results suggest that the S. rivulatus genome assembled in this study has high quality and strong integrity compared to other published teleost genomes.

Genome collinearity analysis

We performed genome synteny analysis between S. rivulatus and C. undulatus50 using JCVI (v1.4.21)51. The results revealed a strong collinearity between the two species, highlighting the high quality of the S. rivulatus genome assembly (Fig. 4).

Ethics statement

The animal experiment was approved by the Committee of the South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (Project No. 201810825825) SCSFRI96-253 and carried out according to applicable standards.

Data availability

The Illumina short-read sequencing, Nanopore long-read sequencing, Hi-C sequencing, and RNA-seq data are available in the NCBI SRA database under the accession number SRP60003344. The genome assembly is deposited at NCBI GenBank under the accession GCA_051912175.145. Data on genome annotations, predicted coding sequences, and protein sequences are available at Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29642444.v1)46.

Code availability

No custom scripts were developed in this study. All data analyses were conducted using publicly available bioinformatics tools, strictly following the manuals and standard protocols provided by their developers, as detailed in the Methods section along with the respective software versions.

References

Brandl, S. J. et al. Extreme environmental conditions reduce coral reef fish biodiversity and productivity. Nat Commun 11, 3832 (2020).

Brandl, S. J. et al. Coral reef ecosystem functioning: eight core processes and the role of biodiversity. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 17, 445–454 (2019).

Dobson, K. L. et al. Ocean acidification does not prolong recovery of coral holobionts from natural thermal stress in two consecutive years. Commun Earth Environ 5, 1–16 (2024).

Rodrigues, R. R., Gonçalves Neto, A. H., Vieira, E. A. & Longo, G. O. The severe 2020 coral bleaching event in the tropical Atlantic linked to marine heatwaves. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1–9 (2025).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming transforms coral reef assemblages. Nature 556, 492–496 (2018).

Stuart-Smith, R. D., Brown, C. J., Ceccarelli, D. M. & Edgar, G. J. Ecosystem restructuring along the Great Barrier Reef following mass coral bleaching. Nature 560, 92–96 (2018).

Cook, D. T., Holbrook, S. J. & Schmitt, R. J. Patterns and implications of spatial covariation in herbivore functions on resilience of coral reefs. Sci Rep 15, 1176 (2025).

Teichert, S., Steinbauer, M. & Kiessling, W. A possible link between coral reef success, crustose coralline algae and the evolution of herbivory. Sci Rep 10, 17748 (2020).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Phase Shifts, Herbivory, and the Resilience of Coral Reefs to Climate Change. Current Biology 17, 360–365 (2007).

Pombo-Ayora, L., Coker, D. J., Carvalho, S., Short, G. & Berumen, M. L. Morphological and ecological trait diversity reveal sensitivity of herbivorous fish assemblages to coral reef benthic conditions. Marine Environmental Research 162, 105102 (2020).

Nanami, A. Nocturnal substrate association of four coral reef fish groups (parrotfishes, surgeonfishes, groupers and butterflyfishes) in relation to substrate architectural characteristics. PeerJ 12, e17772 (2024).

Rocha, C. M. C. & Sampaio, C. L. S. A review of the knowledge of reef fish in the Southwest Atlantic. Marine Environmental Research 182, 105769 (2022).

Nalley, E. M., Donahue, M. J. & Toonen, R. J. Metabarcoding as a tool to examine cryptic algae in the diets of two common grazing surgeonfishes, Acanthurus triostegus and A. nigrofuscus. Environmental DNA 4, 135–146 (2022).

Tebbett, S. B., Goatley, C. H. R. & Bellwood, D. R. Fine sediments suppress detritivory on coral reefs. Marine Pollution Bulletin 114, 934–940 (2017).

Krone, R., Paster, M. & Schuhmacher, H. Effect of the surgeonfish Ctenochaetus striatus (Acanthuridae) on the processes of sediment transport and deposition on a coral reef in the Red Sea. Facies 57, 215–221 (2011).

Burkepile, D. E. & Hay, M. E. Impact of herbivore identity on algal succession and coral growth on a Caribbean reef. PLoS One 5, e8963 (2010).

Gordon, S. E., Goatley, C. H. R. & Bellwood, D. R. Low-quality sediments deter grazing by the parrotfish Scarus rivulatus on inner-shelf reefs. Coral Reefs 35, 285–291 (2016).

Cramer, K. L., O’Dea, A., Clark, T. R., Zhao, J. & Norris, R. D. Prehistorical and historical declines in Caribbean coral reef accretion rates driven by loss of parrotfish. Nat Commun 8, 14160 (2017).

Smith, L. L., Fessler, J. L., Alfaro, M. E., Streelman, J. T. & Westneat, M. W. Phylogenetic relationships and the evolution of regulatory gene sequences in the parrotfishes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 49, 136–152 (2008).

Pereira, P. H. C., Santos, M., Lippi, D. L. & Silva, P. Ontogenetic foraging activity and feeding selectivity of the Brazilian endemic parrotfish Scarus zelindae. PeerJ 4, e2536 (2016).

Shimose, T., Kanaiwa, M. & Nanami, A. Influence of the flesh quality and body size on the auction price of parrotfishes (Scaridae) at tropical island, southern Japan: Implications for fisheries management. Regional Studies in Marine Science 25, 100489 (2019).

The dominance of non-indigenous species in the catch composition of small-scale fisheries. A case study from the Kaş–Kekova Special Environmental Protection Area, Türkiye, Eastern Mediterranean. Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria 53, 27–35 (2023).

Wang, Z., Ran, M., Liu, X., Zhou, C. & Song, Z. Chromosome-level genome assembly of rock carp (Procypris rabaudi). Sci Data 12, 914 (2025).

Zhang, D.-C. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of golden pompano (Trachinotus ovatus) in the family Carangidae. Sci Data 6, 216 (2019).

Xiao, Y., Xiao, Z., Ma, D., Liu, J. & Li, J. Genome sequence of the barred knifejaw Oplegnathus fasciatus (Temminck & Schlegel, 1844): the first chromosome-level draft genome in the family Oplegnathidae. Gigascience 8, giz013 (2019).

Wingett, S. W. & Andrews, S. FastQ Screen: A tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Res 7, 1338 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. Gigascience 7, 1–6 (2018).

Liu, B. et al. Estimation of genomic characteristics by analyzing k-mer frequency in de novo genome projects. arXiv.org https://arxiv.org/abs/1308.2012v2 (2013).

Hu, J., Fan, J., Sun, Z. & Liu, S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics 36, 2253–2255 (2020).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170.

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell Syst 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal3327 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox Provides a Visualization System for Hi-C Contact Maps with Unlimited Zoom. cels 3, 99–101 (2016).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Yan, H., Bombarely, A. & Li, S. DeepTE: a computational method for de novo classification of transposons with convolutional neural network. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa519.

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics Chapter 4, 4.10.1–4.10.14 (2009).

Stanke, M. & Waack, S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics 19(Suppl 2), ii215–225 (2003).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biology 9, R7 (2008).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol 37, 907–915 (2019).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol 33, 290–295 (2015).

Birney, E., Clamp, M. & Durbin, R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res 14, 988–995 (2004).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240 (2014).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP600033 (2025).

NCBI GenBank. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_051912175.1 (2025).

Liang, Y. A chromosome-level reference genome of the surf parrotfish (Scarus rivulatus). Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29642444.v1 (2025).

Seppey, M., Manni, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: Assessing Genome Assembly and Annotation Completeness. Methods Mol Biol 1962, 227–245 (2019).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10, giab008 (2021).

Liu, D. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the endangered humphead wrasse Cheilinus undulatus: Insight into the expansion of opsin genes in fishes. Mol Ecol Resour 21, 2388–2406 (2021).

Tang, H. et al. JCVI: A versatile toolkit for comparative genomics analysis. Imeta 3, e211 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Seed Industry Revitalization Project of Special Fund for Rural Revitalization Strategy in Guangdong Province (2023-SBH-22-002), National Marine Genetic Resource Center, and Central Public-Interest Scientific Basal Research Fund, CAFS (2023TD33), China Agriculture Resarch system for Marine Fish Culture Industry(CARS-47).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C.Z. conceived and designed the study. B.S.L. and N.Z. collected samples, K.C.Z. and H.Y.G. performed molecular work. Y.L., J.M.P. and X.L. performed bioinformatic analysis. Y.L. and J.M.P. wrote initial draft of the manuscript. D.C.Z., Y.L. and J.M.P. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, Y., Pan, J., Xian, L. et al. A chromosome-level reference genome of the surf parrotfish (Scarus rivulatus). Sci Data 12, 1921 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06195-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06195-y