Abstract

We introduce a novel multimodal emotion recognition dataset designed to enhance the precision of valence-arousal modeling while incorporating individual differences. This dataset includes electroencephalogram (EEG), electrocardiogram (ECG), and pulse interval (PI) data from 64 participants. Data collection employed two emotion induction paradigms: video stimuli targeting different valence levels (positive, neutral, and negative) and the Mannheim Multicomponent Stress Test (MMST) inducing high arousal through cognitive, emotional, and social stressors. To enrich the dataset, participants’ personality traits, anxiety, depression, and emotional states were assessed using validated questionnaires. By capturing a broad spectrum of affective responses and systematically accounting for individual differences, this dataset provides a robust resource for precise emotion modeling. The integration of multimodal physiological data with psychological assessments lays a strong foundation for personalized emotion recognition. We anticipate this resource will support the development of more accurate, adaptive, and individualized emotion recognition systems across diverse applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Emotion recognition plays a vital role in various fields, including mental health support, human-computer interaction, education, and marketing. By accurately identifying and measuring emotional states, emotion recognition could create more personalized experiences, enhance user engagement, and support individuals’ mental health and well-being1,2. For instance, in mental health, emotion recognition could monitor fluctuations in an individual’s mood in real-time, facilitating the early detection of risks for psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety3, which allows for timely interventions.

In recent years, advancements in the interdisciplinary fields of affective computing and neuroscience have significantly accelerated the development of emotion recognition technology2. Furthermore, progress in deep learning algorithms and multimodal data fusion has greatly improved the accuracy and adaptability of emotion recognition systems4.

Existing multimodal emotion datasets, such as DEAP5, AMIGOS6, and SEED-VII7, have significantly advanced the field by integrating diverse physiological signals, including electroencephalography (EEG), electrocardiography (ECG), and self-reported emotional labels. These datasets have enabled the development of machine learning models that can recognize complex emotional states. However, several limitations still exist8. One major issue is that most current emotion studies rely on the continuous emotional model to differentiate between valence but do not address the distinctions in arousal6,9. Additionally, while individual differences such as personality traits and anxiety levels are known to significantly impact emotional processing, there is a lack of comprehensive datasets that systematically incorporate these factors8. This gap restricts the depth of analysis, particularly in understanding how personal characteristics influence emotional responses under various conditions.

To address these limitations, we introduce a novel multimodal emotion recognition dataset aimed at improving the precision of emotional dimension modeling while systematically accounting for individual variability. Our approach builds upon the well-established two-dimensional model of emotion, which characterizes emotions along the orthogonal dimensions of valence and arousal10.

To comprehensively capture emotional variability, we integrate two complementary emotion elicitation paradigms: video-based emotion induction and the Mannheim Multicomponent Stress Test (MMST). While both methods provide data on valence and arousal, they offer distinct advantages in eliciting specific emotional responses. Video-based tasks are particularly effective in inducing a wide range of emotional valence—including positive, negative, and neutral states—while simultaneously triggering moderate levels of arousal. In contrast, the MMST is specifically designed to elicit high arousal through stress-inducing components such as time constraints, negative feedback, and cognitive load, leading to valence shifts associated with stress responses11.

By combining these two paradigms, our approach ensures broad coverage of emotional states, spanning low to high arousal and encompassing the full spectrum of valencee, respectively. This design enhances the ecological validity and diversity of the dataset, making it a robust resource for advancing emotion recognition research.

In addition to comprehensive emotional dimension modeling, our dataset integrates assessments of individual differences to explore their influence on emotional processing. Participants completed a series of psychometrically validated questionnaires designed to measure personality traits, anxiety, depression, and life events. By incorporating these individual characteristics, the database supports the development of personalized emotion recognition models, which can account for variability across different user profiles and improve the adaptability of affective computing systems.

Regarding data collection, we combined high-precision physiological recording techniques with exploratory applications of wearable device technology. EEG and ECG data were collected using laboratory-grade equipment, whereas pulse interval (PI) data were obtained from wrist-worn wearable devices. Although wearable technology is currently constrained by accuracy and data resolution limitations, we acknowledge its potential for future large-scale data collection. The portability and ease of use of wearable devices create possibilities for emotion data acquisition in real-world settings, enabling long-term, low-intrusion monitoring of emotional dynamics12,13. This capability not only enhances the ecological validity of emotion recognition models but also supports the development of personalized emotion-aware technologies, such as emotion-adaptive interfaces and mental health monitoring tools14,15.

In summary, this novel multimodal emotion recognition dataset is distinguished by its precise modelling of emotional dimensions and its comprehensive consideration of individual differences. The integration of controlled laboratory data with exploratory wearable device applications establishes the foundation for future scalability and real-world applicability. It is anticipated that this dataset will make a substantial contribution to the advancement of emotion recognition research, thereby fostering the development of more accurate, personalized, and context-aware affective computing systems.

Methods

Participants

A total of 64 university students (33 males and 31 females) participated in this study, with ages ranging from 19 to 26 years (M = 22.06, SD = 2.08). Participants were recruited through advertisements at universities in Beijing. All individuals were physically and mentally healthy. Inclusion criteria required participants to be over 18 years old, enrolled in college, not currently using psychotropic medications, and free from significant neurological or cardiovascular conditions. Exclusion criteria included the use of psychiatric medications within the past six months, a diagnosis of major mental health disorders such as schizophrenia or major depressive disorder, and any physiological abnormalities affecting cardiac function. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. H22130). All participants gave written informed consent prior to their involvement, agreeing to both study participation and the anonymized sharing of their data.

Procedure

To thoroughly sample the emotional spectrum, we employed two complementary emotion induction paradigms: (1) affective video viewing and (2) the Mannheim Multicomponent Stress Test (MMST). The video-based paradigm was designed to evoke discrete emotional states varying in valence (positive, neutral, negative), while the MMST was used to induce high-arousal affective states. This dual-approach design provides comprehensive coverage of the valence-arousal continuum, thereby aligning with established methodological standards in affective neuroscience.

The experiment was divided into three distinct phases (see Fig. 1).

In the first phase, participants were instructed to relax while completing a questionnaire and undergoing physiological data collection. This phase, corresponding to a calm state, served as the baseline reference for subsequent emotional change.

In the second phase, participants underwent the emotion induction phase, which involved watching video clips corresponding to different emotional valences (positive, neutral, negative). For the first thirty participants, the viewing order was positive, neutral, and then negative; for the remaining participants, the order was reversed to negative, neutral, and then positive. This counterbalancing minimized potential carryover effects between emotional states. At the end of each video, participants completed Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) ratings to evaluate both valence and arousal, providing subjective reports of their emotional responses to the viewed materials.

In the third phase, participants first watched a two-minute neutral video to stabilize their emotional state following the emotion induction phase. They then proceeded to perform the MMST, during which SAM ratings were obtained at 0, 3, 6, and 8 minutes, while EEG, ECG, and PI data were continuously recorded.

Stimuli

Video clips

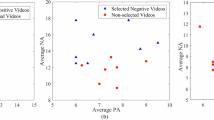

To ensure emotional efficacy, a pre-experiment was conducted with 55 college students who rated the emotional intensity and differentiation of candidate clips. The final selections demonstrated strong emotional induction effects, validated through subjective ratings on a four-point Likert scale.

The video materials were classified into three categories according to emotional valence, with each video lasting for 10 minutes.

-

1.

Positive: humorous short clips sourced from Chinese internet media platforms to evoke positive emotions.

-

2.

Neutral: videos depicting everyday objects and landscapes with neutral background music to maintain a baseline emotional state.

-

3.

Negative: documentary footage featuring interviews with left-behind children to elicit negative emotions.

MMST paradigm

The Mannheim Multicomponent Stress Test (MMST) combines five distinct stressors to elicit a heightened state of arousal. Cognitive stress was induced using the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT)16, in which participants added consecutive numbers and selected the correct answer from 21 options within approximately 3.5 seconds per trial. Real-time feedback was provided throughout the 8-minute task. Additionally, participants performed the arithmetic task while emotionally aversive images from the Geneva Affective Picture Database (GAPED)17 were presented simultaneously, thereby incorporating an emotional stressor. Acoustic stress was introduced via countdown signals and explosion-like noises that intensified after incorrect responses. A motivational stressor was implemented by deducting monetary amounts from an initial balance for incorrect or delayed responses. Finally, social evaluative stress was applied through on-screen feedback, especially at the third and fifth minutes, indicating that performance was delivered through on-screen feedback indicating that performance was below average compared to peers. All five stressors were applied simultaneously, except for the social stressor, which was introduced at the 3rd minute and remained visible thereafter. To further increase task difficulty, only responses made within a designated central area on the screen were accepted; any responses outside this area were deemed invalid regardless of correctness.

Measures

Participants completed a series of questionnaires and self-assessment scales to evaluate demographic information, personality traits, anxiety, depression.

Demographic information questionnaire

Collected basic demographic data, including gender, age.

Psychological measures

Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory-15 (CBF-PI-15): assessed personality traits across the five dimensions, openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism, using 15 items rated on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree)18.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): measured the severity of depressive symptoms through 9 items rated on a 4-point scale (0 = not at all, 3 = nearly every day)19.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI): evaluated trait anxiety levels through 20 items rated on a 4-point scale (1 = seldom, 4 = almost always)20.

Adolescent Self-Rating Life Events Checklist (ASLEC): assessed the frequency and intensity of recent life events and associated stress with 27 items rated on a 6-point scale (0 = not at all, 5 = extremely)21.

Subjective emotional experience

SAM: quantified participants’ current emotional valence and arousal levels22, using a graphical representation with a 9-point scale, later converted to a 1–5 scale in increments of 0.5, shown in Fig. 2.

Equipment

An illustration of the experimental scene is presented in Fig. 3, depicting the participant’s seating arrangement, stimulus presentation setup, and physiological recording configuration.

Experimental Setup for Multimodal Physiological Data Collection. Participants wore an EEG cap to record brain activity, while ECG electrodes were placed on the chest and lower rib area to monitor heart activity. A wrist-worn wearable device was used to collect pulse interval (PI) data. The participant performed tasks on a computer while physiological signals were continuously recorded.

ECG equipment

ECG data were collected using the Biopac MP150 system equipped with an ECG module, which recorded single-channel ECG signals. Before data acquisition, the skin was cleaned with alcohol and the disposable electrodes were affixed to three locations: the right clavicular midline at the sternal notch level, the left lower rib middle area, and the right lower abdominal area (ground). Data were captured using AcqKnowledge 4.2 software at a sampling rate of 2000 Hz.

EEG equipment

EEG signals were collected using the NeuroScan system with 64 electrodes arranged according to the 10–20 system. The online reference electrode was placed on the left mastoid, while the offline reference was the arithmetic average of the bilateral mastoids. The ground electrode was positioned between FPz and Fz. Vertical eye movement electrodes were placed above and below the left eye, and horizontal eye movement electrodes were placed laterally on both sides of the eyes. Data collection and real-time monitoring were performed using Scan 4.5 software.

PI Data collection

PI refers to the time between consecutive pulse waves, reflecting the variability in heartbeats over time (See Fig. 4). PI data were collected using the consumer-grade Huawei Band 7. The device sampled data at 25 Hz, capturing data on a per-minute basis. The data were transmitted via Bluetooth for further analysis.

Software for data processing

Data preprocessing was conducted using Python with the following packages. EEG and ECG data preprocessing were performed using the MNE toolkit, RRI values were extracted from the ECG data using NumPy, outlier filtering for PI data was done using the HRV package, and the analysis of PI values was carried out using the NeuroKit2 package23.

Data preprocessing

The dataset comprises EEG, ECG, and PI signals collected from 64 participants. All data segments are meticulously labeled with valence and arousal scores to facilitate comprehensive emotion recognition tasks. The preprocessing pipeline ensures data quality, consistency, and precise temporal alignment across the different physiological modalities.

EEG data preprocessing

Initially, spherical spline interpolation was performed to correct any bad channels in the EEG recordings. Subsequently, the data were filtered using a fourth-order zero-phase Butterworth bandpass filter with a frequency range of 0.5 Hz to 45 Hz to remove unwanted noise. Artifact-contaminated segments were then automatically identified and removed based on excessive high-frequency activity. Next, Independent Component Analysis (ICA) was applied to further eliminate artifacts such as eye blinks, cardiac signals, and movement-related noise. Finally, the cleaned EEG data were segmented into 4-second epochs according to the emotional labels and synchronized with the ECG data. After preprocessing, the EEG data were segmented into 4-second non-overlapping epochs. This segmentation was based on the annotated emotional labels and aligned with the corresponding ECG signals. A 4-second epoch length is widely used in EEG research due to its demonstrated reliability in providing both frequency resolution and temporal stability, as supported by multiple studies24,25.

ECG data preprocessing

Initially, the raw ECG data were filtered using a high-pass filter at 0.5 Hz, a 5th-order Butterworth filter, and a notch filter at 50 Hz to eliminate power line interference. Then the data were segmented based on emotional labels into 4-second intervals for subsequent statistical analysis. R-wave detection was performed based on the absolute gradient of the ECG signals, identifying the peaks corresponding to heartbeats. Subsequently, RRI, defined as the time between consecutive R-wave peaks, was calculated for further analysis.

PI Data preprocessing

Anomaly filtering was performed to eliminate outliers and artifacts. Due to the minute-by-minute sampling rate of the PI data, only short-term heartbeat dynamic features could be extracted, limiting the analysis of long-term heart rate variability metrics.

Emotional labeling

To characterize affective states, we implemented two complementary classification tasks: binary-class arousal and four-class valence. The experimental protocol was designed to evoke distinct emotional states in participants, with physiological data labeled according to the experimental conditions. For the four-class valence classification, calm served as the baseline emotion, whereas positive, negative, and neutral states were induced via exposure to corresponding video clips. In the binary-class arousal classification, calm again acted as the baseline, with stress elicited by the Mannheim Multicomponent Stress Test (MMST). Physiological data segments were labeled according to these experimental conditions. These dual classification schemes effectively capture both arousal-based and valence-based distinctions, providing a robust framework for modeling emotional states.

Data Records

The data files are accessible through the Science Data Bank via the following DOI link: https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.23231. To download the data, please register an account on the Science Data Bank website and use the provided link to access the dataset26.

As shown in Fig. 5, the dataset was organized into four sections, and a ‘Metadata.txt’ file was included in dataset to provide detailed information about each file:

-

1.

Physiological Data

-

(1)

EEG_raw: Each file contains 64-channel EEG data for one subject (the data of subjects 02 and 03 are split into two) in .cnt format. For channel information, see EEG_channel_order.xlsx.

-

(2)

ECG_raw: Each file contains ECG data for one subject (the data of subjects 02 and 03 are split into two) in.acq format.

-

(3)

PI_raw: Each file contains one day’s PI data collected via a wearable device in.csv format, containing three columns of information: device number, time and PI data.

-

(4)

ECG_EEG_emo: Each file contains time-aligned EEG and ECG data segmented into 4-second epochs (non-overlapping) with corresponding emotion labels (.fif format). For channel information, see ECG_EEG_channel_order.xlsx.

-

(5)

PI_emo.csv: This file contains PI data segmented by emotional states for each subject, each row containing time, PI, label, and name.

-

(6)

EEG_preprocessed: Each file contains preprocessed EEG data in.fif format from ECG_EEG_emo. The data are segmented into 4-second intervals.

-

(7)

ECG_preprocessed: Each file contains preprocessed ECG data in.npy format from ECG_EEG_emo. The data are segmented into 4-second intervals.

-

(8)

PI_preprocessed: Each file contains 1 minute long preprocessed PI data in.txt format, with label in the file name.

-

(1)

-

2.

Questionnaire Data

-

(1)

Demographic_Information.xlsx: This file contains demographic details of all participants, with each row corresponding to an individual subject, including the following information: participation number, sex, age, Big Five personality, trait anxiety, depression, score of life events.

-

(2)

SAM.xlsx: This file stores SAM ratings, documenting valence and arousal scores across different experimental phases.

-

(1)

-

3.

Channel Order

-

(1)

EEG_order.xlsx: This file provides the 64 EEG channel order information.

-

(2)

EEG_ECG_order.xlsx: This file provides the channel order of time-aligned EEG and ECG Data.

-

(1)

-

4.

Stimuli

-

(1)

Positive video: short humorous clips sourced from Chinese media platforms.

-

(2)

Neutral video: scenic footage with soft instrumental music.

-

(3)

Negative video: documentary excerpts featuring interviews with left-behind children.

-

(1)

Technical Validation

Effectiveness of emotion induction

Participants’ self-reported ratings on the SAM scale were analyzed to assess the effectiveness of emotion induction. As shown in Fig. 6, affective videos produced specific valence ratings: calm (M = 3.58, SD = 0.56), negative (M = 2.18, SD = 0.74), neutral (M = 3.52, SD = 0.65), and positive (M = 4.31, SD = 0.65), with the result of variance analysis showing significant differences (F = 119.46, p < 0.001). The stress phase was rated as having significantly higher arousal (M = 3.30, SD = 0.90) compared to the calm (M = 1.70, SD = 0.64), with a t-test confirming a significant difference (p < 0.001). These results confirm that the targeted emotional states were successfully induced.

Descriptive statistics for psychological measures

Descriptive statistics for the assessed personality traits and psychological variables are presented in Table 1. We compared these factors across genders and found no statistically significant differences.

Model implementation

Initially, features were extracted from the preprocessed data. For EEG signals, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to reduce spatial dimensionality, and the first 10 principal components were retained. The cumulative variance explained by the principal components reached 75%. Frequency-domain features as well as time-domain and time-frequency features, were computed for each component, yielding a total of 80 features. RRI was extracted from ECG data, and a comprehensive set of 94 features was computed using time-domain, frequency-domain, and nonlinear analysis. An identical feature extraction procedure was applied to the PI data; however, due to the per-minute aggregation of PI data, the analysis was restricted to short-term heart rate dynamics, resulting in 78 features. The complete list of features can be found in the supplementary materials.

Next, predictive models were constructed for emotional valence and emotional arousal using multiple machine learning and deep learning algorithms. The models included traditional machine learning techniques such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest, Decision Trees, and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), along with deep learning models such as Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) and 1D Convolutional Neural Networks (1dCNN).

We present a detailed description of the 1dCNN architecture here. The structures of the other models were included in the supplementary materials. For binary classification tasks, the 1dCNN model consisted of.three convolutional blocks with kernel sizes of 1, 3, and 5, with the number of filters increasing from 32 to 128. Each block included batch normalization, ReLU activation, max pooling, and dropout (rate = 0.5). A global average pooling layer and a dense layer with 64 units preceded the final sigmoid output. For four-class classification, the model included four convolutional blocks (kernel sizes: 1, 3, 3, 5; filters: 64 - 256), each followed by batch normalization, LeakyReLU activation (α = 0.1), pooling, and dropout (rate = 0.3). Two dense layers (128 and 64 units) preceded the final SoftMax output. Both models were trained using the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.0005) with appropriate cross-entropy loss functions.

Model performance was assessed using 10-fold stratified cross-validation, where all samples from all subjects were pooled together and then randomly split in each fold (90% for training and 10% for validation). This procedure ensured that the class distribution was preserved across folds while providing robust performance estimates.

Performance evaluation

As shown in the Table 2 and Fig. 7, the 1dCNN model outperformed traditional machine learning models in predicting both emotional valence and arousal, with accuracies of 90.46% and 93.44% for the EEG-based model, 82.00% and 86.65% for the ECG-based model, and 73.23% and 73.92% for the PI-based model, respectively. Despite the moderate performance of the PI-based models, their suitability for long-term, low-intrusion monitoring underscores their practical applicability in real-world emotion recognition systems.

In addition to the four-class and binary-class arousal analyses, we further performed a three-class classification task using only the video-induced emotional states (negative, neutral, positive). The classification models achieved robust performance across modalities. EEG achieved the highest performance with an average accuracy of 0.87, whereas ECG and PI followed with 0.84 and 0.76, respectively. These findings are consistent with widely adopted protocols and further support the effectiveness of multimodal physiological signals for emotion recognition.

In this study, we present a comprehensive multimodal emotion recognition dataset aimed at improving the precision of Valence-Arousal Model while systematically incorporating individual differences. By integrating EEG, ECG, and PI signals collected under controlled emotional stimuli, this dataset serves as a valuable resource for advancing research in emotion recognition and computational affective science.

Although the MMST has been widely validated as an effective paradigm for inducing stress and high arousal (Reinhardt et al., 2012), it should be noted that its multimodal stressors differ from the neutral video used in the calm baseline, which may introduce potential confounding effects. To further minimize such risks, future studies could consider employing more unified or comparable stimulus materials across conditions.

Future studies can also expand the dataset to include a larger and more diverse population across different age groups, cultural backgrounds, and real-world scenarios. Furthermore, enhancing the real-time performance and robustness of emotion recognition systems is crucial. By refining data diversity and enhancing real-time processing capabilities, emotion recognition systems can achieve enhanced accuracy and applicability in everyday settings and human-computer interaction.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study has been deposited in the Science Data Bank repository and is publicly available via the following: https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.23231.

Code availability

The data preprocessing and validation procedures presented in the validation section were conducted in Python. The data analysis code are included in the dataset26.

References

Cai, Y., Li, X. & Li, J. Emotion recognition using different sensors, emotion models, methods and datasets: A comprehensive review. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 23, 2455, https://doi.org/10.3390/s23052455 (2023).

Saganowski, S. et al. Emognition dataset: Emotion recognition with self-reports, facial expressions, and physiology using wearables. Sci. Data 9, 158, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01262-0 (2022).

Cohen, A. S., Kim, Y. & Najolia, G. M. Psychiatric symptom versus neurocognitive correlates of diminished expressivity in schizophrenia and mood disorders. Schizophrenia Research 146, 249–253, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.002 (2013).

Ezzameli, K. & Mahersia, H. Emotion recognition from unimodal to multimodal analysis: A review. Inf. Fusion 99, 101847, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2023.101847 (2023).

Koelstra, S. et al. DEAP: A database for emotion analysis using physiological signals. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 3, 18–31, https://doi.org/10.1109/T-AFFC.2011.15 (2012).

Miranda Calero, J. A. et al. WEMAC: Women and Emotion Multi-modal Affective Computing dataset. Sci. Data https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04002-8 (2024).

Jiang, W.-B. et al. SEED-VII: A multimodal dataset of six basic emotions with continuous labels for emotion recognition. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAFFC.2024.3245678 (2024).

Ramaswamy, M. P. A. & Palaniswamy, S. Multimodal emotion recognition: A comprehensive review, trends, and challenges. WIREs Data Mining Knowl. Discov. 14, e1563, https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1563 (2024).

Katsigiannis, S. & Ramzan, N. DREAMER: A database for emotion recognition through EEG and ECG signals from wireless low-cost off-the-shelf devices. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 22, 98–107, https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2017.2688239 (2018).

Zhao, S., Jia, G., Yang, J., Ding, G. & Keutzer, K. Emotion recognition from multiple modalities: Fundamentals and methodologies. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 38, 59–73, https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2021.3106895 (2021).

Reinhardt, T., Schmahl, C., Wüst, S. & Bohus, M. Salivary cortisol, heart rate, electrodermal activity and subjective stress responses to the Mannheim Multicomponent Stress Test (MMST). Psychiatry Res. 198, 106–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.009 (2012).

Lee, S., Kim, H., Park, M. J. & Jeon, H. J. Current advances in wearable devices and their sensors in patients with depression. Front. Psychiatry 12, 672347, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.672347 (2021).

Wijasena, H. Z., Ferdiana, R. & Wibirama, S. A survey of emotion recognition using physiological signal in wearable devices. Int. Conf. Artif. Intell. Mech. Syst. (AIMS) 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/AIMS52415.2021.9466092 (2021).

Kwon, J., Ha, J., Kim, D.-H., Choi, J. W. & Kim, L. Emotion recognition using a glasses-type wearable device via multi-channel facial responses. IEEE Access 9, 146392–146403, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3121543 (2021).

Shu, L. et al. Wearable emotion recognition using heart rate data from a smart bracelet. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 20, 718, https://doi.org/10.3390/s20030718 (2020).

Lejeuz, C. W., Kahler, C. W. & Brown, R. A. A. modified computer version of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT) as a laboratory-based stressor. Behav. Ther. 26, 290–293, https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100463 (2003).

Dan-Glauser, E. S. & Scherer, K. R. The Geneva affective picture database (GAPED): a new 730-picture database focusing on valence and normative significance. Behav Res 43, 468–477, https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0064-1 (2011).

Zhang, X., Wang, M.-C., He, L., Jie, L. & Deng, J. The development and psychometric evaluation of the Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory-15. PLoS ONE 14, e0221621, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221621 (2019).

Wang, W. et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 36, 539–544, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.05.021 (2014).

Spielberger, C. D., Gonzalez-Reigosa, F., Martinez-Urrutia, A., Natalicio, L. F. S. & Natalicio, D. S. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Rev. Interam. Psicol./Interam. J. Psychol. 5, Article 3 & 4, https://doi.org/10.30849/rip/ijp.v5i3 (2017).

Liu, X. et al. The adolescent self-rating life events checklist and its reliability and validity. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 5, 34–36, https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1000-9817.1997.01.010 (1997).

Bradley, M. M. & Lang, P. J. Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 25, 49–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9 (1994).

Makowski, D. et al. NeuroKit2: A Python toolbox for neurophysiological signal processing. Behav. Res. Methods 53, 1689–1696, https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01516-y (2021).

Zheng, W. L., Zhu, J. Y. & Lu, B. L. Identifying stable patterns over time for emotion recognition from EEG. IEEE transactions on affective computing 10, 417–429, https://doi.org/10.1109/TAFFC.2017.271214 (2017).

Rozgić, V., Vitaladevuni, S. N. & Prasad, R. Robust EEG emotion classification using segment level decision fusion. 2013 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing, 1286–1290, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2013.6637858 (2013).

Huang, X. EVA-MED: An Enhanced Valence-Arousal Multimodal Emotion Dataset for Emotion Recognition. Science Data Ban https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.23231 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development projects under Grant number 2023YFC3605304.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xin Huang: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing. Shiyao Zhu: Data curation, Writing-review and editing. Ziyu Wang: Writing-review and editing. Yaping He: Writing-review and editing. Zhenyu Zou: Data curation, Validation. Jingyi Wang:Writing-review and editing, Validation. Hao Jin: Supervision, Validation, Funding acquisition. Zhengkui Liu: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Zhu, S., Wang, Z. et al. An Enhanced Valence-Arousal Multimodal Emotion Dataset for Emotion Recognition. Sci Data 12, 1944 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06214-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06214-y