Abstract

The Disruption Index (DI) is a significant metric for identifying research that expands scientific frontiers and pioneers new fields. Unlike readily accessible metrics like citation counts, DI requires complex analysis of citation patterns, specifically, how subsequent research that cites a given work also references its foundational predecessors, representing a paradigm shift in assessing scientific impact. Current DI studies remain largely confined to single indicators, disciplines, or databases, lacking comprehensive benchmarks to evaluate the intrinsic properties and temporal dynamics of diverse DI metrics. To bridge this critical gap, we introduce Cross-source Disruption Indexes (CrossDI) dataset, a comprehensive benchmark resource that integrates multiple established DI metrics for key articles across four fields. Curated from three major bibliographic databases (WoS, Dimensions, and OpenCitations), this dataset is designed as a reusable benchmark for the systematic evaluation and comparison of disruption indexes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Scientific disruptions, characterized by their capacity to challenge existing paradigms and redefine research trajectories, serve as critical catalysts for technological breakthroughs and societal transformation1,2,3. Traditional bibliometric indicators (e.g., citation counts) remain limited in capturing the innovative and revolutionary nature of such work, as they predominantly reflect incremental contributions that reinforce existing knowledge rather than displacing it3,4. This gap motivated the development of the Disruption Index (DI), a metric quantifying the extent to which research eclipses foundational references and replaces established practices5.

The DI index operates on a tripartite citation framework (Fig. 1), analyzing relationships among target articles (current generation, square), their cited references (past generation, diamond), and subsequent citing works (future generation, circle). Bibliographic coupling identifies two distinct contribution types: Consolidating contributions (D = −1), where subsequent works co-cite both the target article and its referenced prior works, signaling incremental advancement, and Disruptive contributions (D = 1), where subsequent works cite only the target article, indicating divergence from prior knowledge trajectories6. Valid application requires sufficient citation context3,7, with empirical studies recommending thresholds of ≥5 references and ≥5 citations2,8.

Recent methodological refinements have produced specialized DI variants to address limitations of Disruption Index9. While the earliest alternative, \({{\rm{m}}{DI}}_{1}\)5, remains relatively understudied, subsequent studies focus on distinct challenges. Variants such as \({{DI}}_{1n}\)10, and \({{DI}}_{{\rm{X}} \% }\)11 specifically mitigate noise from highly cited references. Conversely, alternative approaches, including \({{DI}}^{{no}R}\)12, DEP13,14, \({O{rig}}_{{base}}\)15, eliminate dependency on citation thresholds by exclusively analyzing subsequent works that directly cite the focal paper. Moving beyond the conventional binary framework that treats disruption and consolidation as opposing constructs, Chen et al.16 conceptualized them as distinct dimensions and developed corresponding indices (D for Destabilization and C for Consolidation), further introducing the consolidation-disruption disentanglement indexes.

Despite these methodological improvements, existing DI indexes remain susceptible to several types of bias9. First, the use of NR as a denominator introduces inconsistency: NR can exert different effects depending on whether the numerator is positive or negative, which contradicts its theoretical interpretation, consolidating qualities should consistently yield lower or negative scores. Second, the time-dependency of disruption scores remains unresolved, although Bornmann and Tekles17 have recommended a minimum citation window of three years. Third, empirical evidence suggests that the relationship between the number of cited references and disruption scores is non-linear and modulated by discipline, publication age, and the length of the citation window. Fourth, biases may also arise from incomplete coverage within bibliometric databases.

To address these methodological gaps, this study establishes a comprehensive benchmark dataset integrating the Web of Science (WoS), Dimensions, and OpenCitations, hereafter referred to as Cross-source Disruption Indexes (CrossDI)18. The dataset encompasses both established fields (e.g., Synthetic Biology, Astronomy & Astrophysics) and emerging domains (e.g., Blockchain-based Information Systems, Socio-Economic Impacts of Biological Invasions). Within this framework, we systematically compute the full suite of disruption indexes discussed above, including DI, \({{\rm{m}}{DI}}_{1}\), \({{DI}}_{1n}\), \({{DI}}_{{\rm{X}} \% }\), \({{DI}}^{{no}R}\), DEP, \({O{rig}}_{{base}}\), as well as the Destabilization (D) and Consolidation (C) indices, for each article in the dataset, tracking their annual disruption indexes for every year following article up to 2023. In addition, we retain and report key intermediate results and parameters underlying these calculations.

By integrating citation data across multiple databases and providing standardized intermediate variables relevant to different disruption indexes, our dataset enables comprehensive analysis of several types of bias, including database coverage, time window selection, and discipline-specific effects. Ultimately, this resource supports deeper investigation into the intrinsic characteristics and methodological sensitivities of disruption indexes, facilitating more robust and comparative bibliometric studies.

It should be noted that our dataset is supported by our previous works:

-

(1)

Xu et al.19 developed a regular expression-based method to systematically identify and automatically correct various typical DOI errors in cited references from the WoS database, thereby significantly improving the quality of citation data.

-

(2)

Xu et al.20 compares the Disruption Index across the WoS, Dimensions, and OpenCitations, finding that the Dimensions is a more reliable open alternative to the WoS than the OpenCitations.

Methods

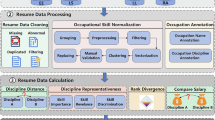

The CrossDI dataset18 is constructed through a systematic workflow that integrates bibliographic metadata from multiple sources. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the generation process comprises three primary phases: (1) Multi-source metadata collection, involving the retrieval of seed articles and their complete citation networks from the WoS, Dimensions, and OpenCitations; (2) Data preprocessing, where key metadata fields, primarily DOIs and publication years, are cleaned and harmonized to ensure cross-database consistency; and (3) Computation of the disruption indexes, which calculates a family of disruption measures from annual citation network snapshots for temporal and cross-source analysis.

Multi-source metadata collection

The CrossDI dataset is constructed through a systematic integration of bibliographic metadata from three major sources: Web of Science Core Collection (https://www.webofscience.com), Dimensions (https://www.dimensions.ai/), and OpenCitations (https://search.opencitations.net/). The seed articles for the dataset are derived from four distinct research areas. For established fields, the SynBio dataset (2003–2012) comprises 2,584 article records obtained by executing the reproducible search strategy provided by Porter et al.21 and Xu et al.22,while the Astro dataset (2003–2010) utilizes the curated bibliographic data assembled by Gläser et al.23 and Xu et al.24. For emerging domains, the Block-Based Information System Management dataset (2019–2022) was compiled from the reference list of Lei and Ngai25 and the Socio-Economic Impacts of Biological Invasions dataset (2019–2022) was built by applying the search strategy from Diagne et al.26. A stratified random sample of 10 articles per publication year is drawn from each of these source collections to form the final set of target articles. The complete list of DOIs for the final set of 260 target articles is provided as part of the CrossDI dataset18.

For each seed article, the complete citation network, including metadata, cited references, and citing articles, is retrieved from all three sources. Metadata from the WoS is manually exported, while data from the Dimensions is collected programmatically via its API (https://app.dimensions.ai/api/dsl/v2), and data from the OpenCitations is collected via its API. The integration of these heterogeneous data streams is governed by a consistent, DOI-centric methodology. Citation relationships are systematically constructed through DOI linkages across three dimensions: (1) from target articles to their cited references, (2) from target articles to their citing articles, and (3) between the cited references and the citing articles. Citing-article coverage is truncated at the end of 2023; only citations appearing through 2023 are included.

DOI extraction required distinct approaches across sources: the WoS and Dimensions necessitate metadata parsing for DOI retrieval, whereas the OpenCitations provides direct citation linkages through its dual-dataset architecture. The OpenCitations infrastructure maintains two principal resources: the OpenCitations Index (documenting citing-cited entity pairs with temporal metadata; https://api.opencitations.net/index/v2) and OpenCitations Meta (containing rich bibliographic records; https://api.opencitations.net/meta/v1), as detailed by Heibi et al.27. This structural distinction enables more efficient citation network reconstruction from the OpenCitations compared to other sources requiring DOI extraction from heterogeneous metadata fields.

To mitigate errors from ‘non-linked’ records, publications that lack standard identifiers (e.g., DOIs) in sources such as the WoS, we enforce a deterministic inclusion rule: only references and citing items with valid, matchable DOIs are admitted to the integrated network. This approach ensures a consistent and reproducible matching logic across all sources and minimized the risk of false-positive citation links. This guarantees a fair comparison among the three sources. Furthermore, a data quality filter is applied at the article level, retaining only those seed articles that possessed at least five cited references and five citing articles2 identifiable via DOIs, thereby guaranteeing a meaningful citation structure for subsequent use.

Data preprocessing

Persistent DOI inconsistencies in the WoS induce systemic citation linkage errors, compromising analytical validity19,28. While automated cleaning19 rectifies detectable errors, residual ambiguity persists when multiple DOIs exhibit equivalent plausibility. Our cross-database processing procedure reveals six multi-DOI phenomena20: (1) Multi-publisher attribution; (2) Derivative material linkage; (3) Multilingual versioning; (4) Component disaggregation; (5) Serialized articles; and (6) Erroneous assignment. As detailed in Algorithm 1, for the category 1–5 (non-erroneous multi-DOIs), the DOI with rank 1 in alphabetic order is selected as the preferred one. In addition, it is very popular that publication years are missed or even conflicted across different databases. In this time the most recent year is kept, since this simple operation can correct the vast majority of missed or conflicted publication years (see further).

This reproducible decision framework is crucial for the large-scale harmonization of bibliographic records. Notably, it directly addresses citation redundancy on the platforms such as Dimensions, where multiple DOIs may be assigned to an identical works, resulting in artificial inflation of citation counts. By clamping DOIs from multiple sources, our approach can mitigate such database-induced inflation and thereby enhance the computational validity of disruption metrics. This normalization procedure not only reconciles metadata heterogeneity across the WoS, Dimensions, and OpenCitations but also establishes an interoperable foundation, ensuring methodological consistency and facilitating cross-platform comparability of disruption indexes.

Notwithstanding these strengths, we acknowledge the inherent arbitrariness of our preprocessing rules. The selection of the alphanumerically-first DOI as the canonical identifier, while systematic, may not always represent the authoritative version of record. Similarly, the preference for the most recent publication year, though effective in resolving conflicts, may in some cases differ from the initial online availability. We recognize these as intentional methodological trade-offs, where we have prioritized scalability and reproducibility for cross-database analysis over context-specific precision in every instance.

Calculation of the disruption indexes

The final dataset assembly involved constructing local citation networks for each target article using the DOI linkages. To support temporal analysis, annual citation network snapshots are built from publication year until 2023. Within each snapshot, nine disruption index variants are pre-calculated, grouped into four methodological families as detailed below. All measures are computed independently for the WoS, Dimensions, and OpenCitations databases.

Core and impact-weighted indexes

Funk and Owen-Smith5 introduced the DI1 index, with its calculation formula illustrated in Fig. 3. Let’s consider a scenario where there is a focal article (represented by a black square) and its references (depicted as diamonds). The citing articles can be categorized into three groups: those citing only the focal article (represented by single-ring circles formed by dotted lines, counted as NF), those citing only the focal article’s references (single-ring circles made of solid lines, counted as NR), and those citing both the focal article and its references (double-ring circles, counted as NB).

The original index DI1 ranges in [−1,1] and reflects the direction (disruptive vs consolidating) but not the magnitude of use.

Funk and Owen-Smith5 also proposed the impact-weighted CD index (\({{\rm{m}}{DI}}_{1}\)), with the following formula:

Algorithm 1

Data preprocessing (Reuse prior DOI cleaning + Alphabetical DOI selection + Max-year reconciliation).

Here, mt counts only citations of the target article. This variant mixes direction with magnitude; its scale depends on mt and is therefore not bounded in [−1,1].

Threshold-based variants

A recognized challenge is the potential bias introduced by highly-cited references, which can inflate the NR and NB values. The following variants implement thresholds to mitigate this effect and reduce noise in the citation network10,11. Bornmann et al.10 developed \({{DI}}_{5}\), which required citing articles to reference at least five of the target article’s cited references when calculating the DI1 index.

Additionally, Deng and Zeng11 suggested another disruption index, \({{DI}}_{{\rm{X}} \% }\), which excludes references that fall within the top X% of most-cited articles.

Both DI5 and \({{DI}}_{{\rm{X}} \% }\) utilize thresholds to eliminate the noise caused by highly-cited references. However, these thresholds can be arbitrarily set, potentially introducing biases or subjectivity into the calculation. We acknowledge the inherent arbitrariness in selecting specific threshold values (e.g., 5 references/citations, top X%). Our choices are guided by established conventions in the literature to ensure comparability and robustness1,8,10,29,30. These thresholds represent a pragmatic compromise between mitigating noise from sparse data and maintaining a sufficiently large sample for analysis.

Reference-omitted measures

To avoid threshold arbitrariness and clarify the role of NR, the following several measures omit entirely it. Wu and Yan12 proposed the disruption index, \({{DI}}^{{no}R}\), defined as:

Bu et al.13 introduced \({MR}[{cited\_pub}]\), later termed the Dependency Index (DEP) by subsequent work14, defined as:

Here, TR is the total number of shared references between the focal paper and its citing papers. A higher dependency index indicates a lower level of disruption. To align its interpretive direction with that of the disruption indexes, we adapt the inverse DEP (invDEP) in this study by following the approach of Bittmann et al.14. In more detail, invDEP is calculated by subtracting each DEP value from the sample maximum plus one.

Shibayama and Wang15 introduced a refinement to disruption measurement by shifting the unit of analysis from article-level counts (e.g., NR) to link-level counts within the citing-reference bipartite network. Their base originality index, \({O{rig}}_{{base}}\), is defined as the proportion of non-links in this network, as shown in Eq. (7).

Here, c denotes the citing articles that reference the focal paper, while r represents the references contained in the focal paper. The total counts of citing articles and references are denoted by capital letters C and R, respectively.

Moving beyond the unidimensional trade-off of \({{DI}}_{1}\), Chen et al.16 re-conceptualized technological evolution with a dual-view framework. A single index that forces a choice between disruption and consolidation cannot capture dual technologies that destabilize some predecessors while consolidating others. To operationalize this, they structurally adapted the tripartite network and defines two indices: D (Destabilization) and C (Consolidation).

Here, i denotes an arbitrary reference cited by the target article. \({N}_{F}^{i}\) measures the number of articles citing the target articles but not citing reference i, \({N}_{B}^{i}\) measures the number of articles citing both the target articles and reference i, \({N}_{R}^{i}\) measures number of articles citing reference i but not the target articles, and n measures the total number of references in the target articles.

Data overview

Citation data across four research domains, namely Synthetic Biology, Astronomy and Astrophysics, Blockchain-based Information System Management, and the Socio-Economic Impacts of Biological Invasions, are compiled through the integration of three major bibliographic databases: the WoS, Dimensions, and OpenCitations. Table 1 summarizes, for each field database combination, the number of target articles and the field-level averages of (i) references and (ii) citations.

Data Records

The dataset is openly available on Figshare18 and is organized as a data lake encompassing four research fields: Synthetic Biology (ID = 1), Astronomy & Astrophysics (ID = 2), Blockchain-based Information System Management (ID = 3), and Socio-Economic Impacts of Biological Invasions (ID = 4). A consistent folder and file structure is used for each field, where the placeholder {ID} corresponds to the field number, and {SOURCE} denotes the citation data source (viz., WoS, Dimensions, OpenCitations). The data is structured into five core components for each field:

-

(1)

Article list (doi/dois-{ID}.csv): This file contains two columns: doi and year. It lists all unique articles that constitute the citation network. It is a key methodological point that only the publication years of citing articles are essential for our disruption metrics calculation. Consequently, the year field is guaranteed to be complete for all such articles but is intentionally left blank for cited references, as this information was not required for the analysis.

-

(2)

Citation edges (citations/citations-{ID}-{SOURCE}.csv): This tab-delimited file defines the directed citation relationships with two columns: cited_doi and citing_doi.

-

(3)

Target Articles (target/target-{ID}.csv): This single-column file (header: doi) specifies the focal articles for which disruption metrics are computed.

-

(4)

Results (result/results-{ID}-{SOURCE}.xlsx): This spreadsheet compiles the disruption indexes and metadata for each target article. It includes: metadata (doi, Publication Year, Y (years since publication), Source), Citation counts (NF, NB, NR, \({N}_{B}^{5}\), \({{N}_{F}}_{{new}}\), alias of \({\bar{N}}_{F}\), and \({{N}_{B}}_{{new}}\), alias of \({\bar{N}}_{B}\)), disruption indexes (\({{DI}}_{1}\), \({{\rm{m}}{DI}}_{1}\), \({{DI}}_{5}\), \({{DI}}^{{no}R}\), \({{DI}}_{3 \% }\), DEP, \({\rm{invDEP}},\) \({O{rig}}_{{base}}\), \({Destabilization}(D)\), \(C{onsolidation}(C)\)).

-

(5)

Multi-DOI consolidation (doi/dois-multi-{ID}.csv): No header; each line lists a group of normalized DOIs determined to refer to the same work; the first DOI is taken as the canonical identifier (subsequent DOIs are aliases).

Technical Validation

To quality-control the dataset, we perform three validations: (i) multi-DOI consolidation accuracy (manual stratified audit), (ii) publication-year reconciliation accuracy, and (iii) reference-count consistency versus PDF ground truth; we additionally benchmark coverage overlap against Crossref to surface potential database-induced biases.

Validation of multiple DOI

Different databases frequently assign multiple DOIs to a single article, with Fig. 4 confirming that dual-DOI cases predominate. Manual verification of 100 stratified-sampled merged groups demonstrates 95% deduplication accuracy (cf. Table S1 in Supplementary Information document): 92 groups are correctly consolidated (including identical articles, same-series entries [IDs: 96, 98, 99], or article components [IDs: 91, 95]), while 5 groups are incorrectly merged (IDs: 20, 44, 60, 78, 94; primarily in the OpenCitations). Three groups (IDs: 66, 68, 71) contain unresolvable secondary DOIs but are validated as correct merges via metadata.

Validation of publication year

When reconciling publication years across databases for identical articles, we observe significant year discrepancies. As shown in Fig. 5, the OpenCitations exhibits the highest rate of missing years (9,192 articles), followed by the WoS (97) and Dimensions (4). Figure 6 further reveals temporal patterns in non-missing but conflicting years, indicating that inter-database inconsistency increases over time. To validate our discrepancy-resolution strategy (adopting the maximum year), we perform stratified random sampling by year and manually verify 100 articles. Table S2 in Supplementary Information document shows 12 erroneous assignments within the sample, yielding 88% accuracy. Notably, the maximum year approach introduces temporal bias, particularly for earlier articles.

Validation of references

Database-reported reference counts are benchmarked against ground truth extracted from the resulting PDFs (Figs. 7–10). Across all examined fields (Astronomy & Astrophysics, Blockchain-based Information System Management, Socio-Economic Impacts of Biological Invasions), database counts are consistently less than or equal to the actual reference counts. We argue that a primary reason is that many referenced articles are not assigned any DOI at all. Notably, the Dimensions demonstrates significantly higher reference coverage in emerging fields compared to other databases. Critically, in the field of Synthetic Biology, the OpenCitations or Dimensions reported reference counts substantially exceeding the actual number of references (e.g., articles IDs: 6, 22, 25, 26, 49, 64, 69, 76, 87). In our opinion, this over-counting primarily stems from two mechanisms:

-

(1)

DOI Redundancy: the OpenCitations (and the Dimensions, e.g., ID = 87) treated distinct DOI strings referencing the same underlying article as separate DOIs. Let’s take the article with DOI = https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.186.13.4276-4284.2004 as an example. Its references https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.40.3.722-756.1976 and https://doi.org/10.1128/br.40.3.722-756.1976 (resolving to identical content) are recorded as two distinct citation relationships (IDs: 6, 49, 64, 69, 76, 87).

-

(2)

Extraneous References: Both the OpenCitations and Dimensions include references demonstrably absent from the source article’s reference list and unrelated to its content (e.g., IDs: 22, 25, 26). A representative example is the inclusion of reference with DOI = https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.1.c7 for article with DOI = https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.186.13.4276-4284.2004. In fact, no actual citation relationship between them exists.

Crossref benchmark comparison

The Crossref is chosen as the external validation reference, reflecting its role as the primary DOI registration authority31. Using the 2025 Crossref Public Data File32 (with citations up to 2023), we validate the coverage and completeness of our collected data. Our comparative analysis find that the Dimensions provides the most comprehensive citation coverage, followed by the WoS, with the OpenCitations exhibiting the lowest coverage. However, supervisingly in the Synthetic Biology field, the Crossref’s coverage was lower than the WoS, primarily due to systematic omissions of references in certain key articles.

Figures 11–14 further illustrate the distribution and overlap of records across the WoS, Dimensions, OpenCitations and Crossref in four fields. Each figure utilizes an UpSet plot to display both the total number of citations indexed by each database (left bars) and the size of intersections among them (top bars). For instance, in Fig. 14, the Dimensions contains 2,260,464 citations and the WoS includes 2,025,014 citations, with 165,306 citations shared exclusively between the WoS and Dimensions, absent from the OpenCitations and Crossref. Notably, a substantial number of records are shared among all four databases, indicating considerable overlap in core articles. These findings highlight the necessity of integrating multiple data sources for comprehensive bibliometric analysis and emphasize the risk of coverage bias when relying on a single database.

Usage Notes

Our CrossDI dataset supports a variety of research applications. First, it enables systematic analysis of the properties and dynamic evolution of disruption indexes over time. Annual DI values across multiple variants allow researchers to examine trends and patterns in scientific disruption. Second, the dataset covers both established and emerging fields providing a basis for investigating disciplinary differences in term of disruption indexes. Third, by combining citation data from multiple sources (WoS, Dimensions, and OpenCitations), the dataset allows users to assess how database characteristics and data coverage affect the calculation and interpretation of disruption indexes. Furthermore, standardized intermediate variables are included to help identify sources of methodological bias, such as time window selection or discipline-specific citation practices. This facilitates sensitivity analyses and supports the development of more robust and comparable DI measures. Moving beyond these core applications, the dataset uniquely empowers several advanced research avenues: the structured citation networks facilitate sophisticated citation network mining to model the propagation of disruptive ideas; the comprehensive suite of indicators and their temporal evolution provides a rich feature set for predictive modeling using machine learning; and these standardized metrics enable systematic anomaly detection by revealing scholarly outliers with atypical disruption trajectories. Overall, the dataset offers a harmonized and flexible benchmark for exploring the disruptive nature of scholarly works across disciplines and data infrastructures.

Data availability

The CrossDI dataset generated during this study is openly available in the Figshare repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30356599.

Code availability

The source code for calculating the disruption indexes is available via a github link: https://github.com/pzczxs/CrossDI-Dataset-and-Source-Code.

References

Wu, L., Wang, D. & Evans, J. A. Large teams develop and small teams disrupt science and technology. Nature 566, 378–382, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0941-9 (2019).

Ruan, X., Lyu, D., Gong, K., Cheng, Y. & Li, J. Rethinking the disruption index as a measure of scientific and technological advances. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 172, 121071, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121071 (2021).

Lin, Y., Li, L. & Wu, L. The Disruption Index Measures Displacement Between a Paper and Its Most Cited Reference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.04677 (2025).

Patel, P. A. & Javed Ali, M. Characterizing innovation in science through the disruption index. Seminars in Ophthalmology 37(6), 790–791, https://doi.org/10.1080/08820538.2022.2112851 (2022).

Funk, R. J. & Owen-Smith, J. A dynamic network measure of technological change. Management Science 63(3), 791–817, https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2366 (2017).

Kim, M., Kojaku, S. & Ahn, Y. Y. Uncovering simultaneous breakthroughs with a robust measure of disruptiveness. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.16845 (2025).

Holst, V., Algaba, A., Tori, F., Wenmackers, S. & Ginis, V. Dataset artefacts are the hidden drivers of the declining disruptiveness in science, arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.14583 (2024).

Chen, H., Bornmann, L. & Bu, Y. Dynamic disruption index across citation and cited references windows: Recommendations for thresholds in research evaluation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.07828 (2025).

Leibel, C. & Bornmann, L. What do we know about the disruption index in scientometrics? An overview of the literature. Scientometrics 129(1), 601–639, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04873-5 (2024).

Bornmann, L., Devarakonda, S., Tekles, A. & Chacko, G. Are disruption index indicators con vergently valid? The comparison of several indicator variants with assessments by peers. Quantitative Science Studies 1(3), 1242–1259, https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00068 (2020).

Deng, N. & Zeng, A. Enhancing the robustness of the disruption metric against noise. Scientometrics 128(4), 2419–2428, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04644-2 (2023).

Wu, Q. & Yan, Z. Solo citations, duet citations, and prelude citations: New measures of the disruption of academic papers. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.03461 (2019).

Bu, Y., Waltman, L. & Huang, Y. A multidimensional framework for characterizing the citation impact of scientific publications. Quantitative Science Studies 2(1), 155–183, https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00109 (2021).

Bittmann, F., Tekles, A. & Bornmann, L. Applied usage and performance of statistical matching in bibliometrics: The comparison of milestone and regular papers with multiple measurements of disruptiveness as an empirical example. Quantitative Science Studies 2(4), 1246–1270, https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00158 (2022).

Shibayama, S. & Wang, J. Measuring originality in science. Scientometrics 122(1), 409–427, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03263-0 (2020).

Chen, J., Shao, D. & Fan, S. Destabilization and consolidation: Conceptualizing, measuring, and validating the dual characteristics of technology. Research Policy 50(1), 104115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104115 (2021).

Bornmann, L. & Tekles, A. Disruption index depends on length of citation window. Profesional De La Informacion 28(2), e280207, https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.mar.07 (2019).

Xu, S., Wang, C., An, X. & Liu, J. CrossDI: A comprehensive dataset crossing three databases for calculating disruption indexes. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30356599 (2025).

Xu, S., Hao, L., An, X., Zhai, D. & Pang, H. Types of DOI errors of cited references in Web of Science with a cleaning method. Scientometrics 120, 1427–1437, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03162-4 (2019).

Xu, S., Wang, C., An, X., Deng, Y. & Liu, J. Do OpenCitations and Dimensions serve as an alternative to Web of Science for calculating disruption indexes? Journal of Informetrics 19(3), 101685, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2025.101685 (2025).

Porter, A. L., Chiavetta, D. & Newman, N. C. Measuring tech emergence: A contest. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 159, 120176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120176 (2020).

Xu, S., Hao, L., Yang, G., Lu, K. & An, X. A topic models based framework for detecting and forecasting emerging technologies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 162, 120366, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120366 (2021).

Gläser, J., Glänzel, W. & Scharnhorst, A. Same data-different results? Towards a comparative approach to the identification of thematic structures in science. Scientometrics 111, 981–998, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2296-z (2017).

Xu, S. et al. Overlapping thematic structures extraction with mixed-membership stochastic blockmodel. Scientometrics 117, 61–84, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2841-4 (2018).

Lei, C. F. & Ngai, E. W. Blockchain from the information systems perspective: Literature review, synthesis, and directions for future research. Information & Management, 103856, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2023.103856 (2023).

Diagne, C. et al. InvaCost, a public database of the economic costs of biological invasions worldwide. cientific data 7, 277, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00586-z (2020).

Heibi, I., Moretti, A., Peroni, S. & Soricetti, M. The OpenCitations Index: description of a database providing open citation data. Scientometrics 129(12), 7923–7942, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-05160-7 (2024).

Zhu, J., Hu, G. & Liu, W. DOI errors and possible solutions for Web of Science. Scientometrics 18(2), 709–718, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2980-7 (2019).

Bornmann, L. & Tekles, A. Disruptive papers published in Scientometrics. Scientometrics 120(1), 331–336, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03113-z (2019).

Xu, Z. et al. Quantifying the disruptiveness of a paper by analyzing how it overshadows its successors. Journal of Informetrics 19(3), 101706, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2025.101706 (2025).

Delgado-Quirós, L. & Ortega, J. L. Research entity information and coverage in eight free access scholarly databases. Online Information Review https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-03-2024-0131 (2025).

Crossref. March 2025 Public Data File from Crossref. Crossref https://doi.org/10.13003/87bfgcee6g (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research received the financial support from the National Social Science Foundation of China under grant number 24BTQ066. The bibliometric analysis of this study is conducted using data from Digital Science’s Dimensions platform, whose comprehensive scholarly database provided essential support for our study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.X. and C.C.W. collected and processed the data. J.H.L. assisted in data collection. S.X. and X.A. designed and supervised the study. S.X. and C.C.W. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, S., Wang, C., An, X. et al. CrossDI: A comprehensive dataset crossing three databases for calculating disruption indexes. Sci Data 12, 1974 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06232-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06232-w