Abstract

Thermal traits are crucial to our understanding of the ecology and physiology of ectothermic animals. While rising global temperatures have increasingly pushed research towards the study of upper thermal limits, lower thermal limits and thermal preferences are essential for defining the thermal niche of ectotherms. Through a systematic review of the literature in seven languages, we expanded an existing database of amphibian heat tolerance by adding 1,009 estimates of cold tolerance and 816 estimates of thermal preference across 375 species. AmphiTherm is a comprehensive and reproducible database that contains 4,899 thermal trait estimates from a diverse sample of 659 species (~7.5% of all described amphibians) spanning 38 families. Despite its broad geographic coverage, we report evident gaps across amphibian biodiversity hotspots in Africa, most regions of Asia, central South America, and Western Australia. By providing a more holistic understanding of amphibian thermal tolerance and preferences, AmphiTherm is a valuable resource for advancing research in evolutionary biology, ecophysiology, and biogeography of amphibians, offering insights that are increasingly needed in changing climates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Thermal trait data are crucial to our understanding of the biology and physiology of ectotherms. The recent increase in broad-scale syntheses of ectotherm thermal physiologies demonstrates recurring interest in how these organisms respond to changing thermal environments1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Much of this work has focused on traits relating to heat tolerance, reflecting the urgency to predict the impacts of climate warming on natural populations11,12,13,14,15,16,17. However, climate change also brings an increased probability of extreme weather events, including negative temperature anomalies18,19. As such, a sole focus on heat tolerance provides an incomplete picture of ectotherm responses to climate change. A comprehensive understanding of heat tolerance, cold tolerance, and thermal preference is necessary to fully define ectotherm’s thermal niches and predict their responses to climate change. Below, we briefly emphasise the importance of these thermal traits for amphibians (see8,20,21 for more in depth discussion).

While the significance of heat tolerance in predicting species’ responses to warming climates is well documented1, data on lower thermal limits are equally vital yet often understudied, especially in amphibians, an at-risk, data-deficient group of ectotherms22. Lower thermal limits represent the lower boundary of an organism’s thermal niche and have been included in several data syntheses5,6,8,10. This trait provides key insights into how species might respond to increasing frequency of extreme cold weather events, which can lead to significant population reduction events known as winterkills18,19,23. Gaining understanding of lower thermal limits can thus help predict the sensitivity and resilience of amphibian populations to extreme cold weather events. Moreover, data on lower thermal limits can inform conservation and management strategies, for instance, by identifying microhabitats buffering the effects of extreme cold on activity and survival24.

Preferred body temperatures reflect the temperature optimising overall performance and the most favourable microhabitat in the absence of other biotic and abiotic factors25,26. Knowledge of preferred body temperatures can thus help predict how climate change will affect species distributions and activity patterns24,27,28,29. In particular, thermal preference data can be used to infer behavioural thermoregulation patterns and the microhabitats available for crucial physiological processes30,31,32. While upper thermal limits can help predict acute survival in the face of extreme heat, gradual warming below the upper thermal limit thresholds can make some areas unsuitable for amphibians’ activity needs24. On the contrary, warming can benefit some amphibians in historically cooler climates by increasing activity windows or reducing hibernation times33. As such, thermal preference data can help predict the sublethal effects of climate change. Thermal preferences also, for instance, affect susceptibility to pathogens34,35,36, shape the composition of commensal microbes37,38, and mediate interactions between host and microbial communities39.

Although investigating thermal traits separately provides important knowledge, the study of a combination of thermal traits provides deeper and more comprehensive insights. A simultaneous analysis of upper and lower thermal limits is particularly interesting as it provides an estimation of thermal tolerance breadth21—a measure of the thermal envelope ectotherms can occupy in the absence of other abiotic or biotic factors (e.g., competition, resource availability). When thermal preference is integrated with upper and lower thermal limits, the thermal envelope gains shape, providing additional insights to parameterise models and predict activity and survival in changing environments. For instance, leveraging data on thermal limits and preferred temperatures can help infer past, current, and future distributions of ectothermic species, including assessing potential invasion risk15,40,41,42,43. Parametrising biophysical models with data on thermal limits and preference now also allow more accurate predictions of overall performance, activity windows17,44 and microhabitat heterogeneity17,44,45, strengthening our ability to predict the impacts of climate change on natural populations46,47. From an evolutionary perspective, the integration of different thermal traits can also advance our understanding of the (co)evolution of these traits, and how climate change may shape evolutionary pressures on thermal tolerance and preference6,29,48,49,50,51.

Thermal trait data can also be used to inform conservation efforts. Comparing thermal niche envelopes among amphibians, their microbiota, and potential pathogens can help predict changes in the microbiome and disease risk52,53,54,55,56,57, providing key information on the environment component of the host-pathogen-environment interactions emphasized with the disease triangle concept54. Amphibians are often accessioned into captivity to establish assurance colonies for breeding and eventual reintroduction58. Knowledge of the thermal tolerance and preference of a broad range of species from different habitats can help inform the design of enclosures that better simulate natural thermal variability59,60,61. It is well established that temperature influences captive breeding success of amphibians60. Amphibian husbandry guides recommend setting thermal environments near the preferred temperature of a species, and when practical, providing thermal gradients and thermal cycling60,62. Exposure to environmental conditions via “soft release” or mesocosms prior to reintroduction can also influence survival and success of reintroduction efforts63,64. In addition, understanding thermal constraints on activity, demography, and disease risk enhances our ability to identify habitats suitable for repatriation and reintroduction efforts in endangered species58,65,66.

Therefore, a holistic understanding of amphibian thermal tolerance limits and preferences is essential for defining the fundamental thermal niche of ectotherms and to project their activity, distribution and survival in rapidly changing environments. Here, we expand an existing database on amphibian upper thermal limits1, which has already facilitated global assessments of vulnerability to climate warming17. We conducted systematic searches and aggregated lower thermal limits and thermal preference data from the global literature published in seven languages. In doing so, we expanded thermal niche data for 378 species, providing a stronger foundation for research on amphibian ecology, evolution, and conservation.

Methods

Reporting

We reported the contributions of each author using the CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy) statement67, and MeRIT (Method Reporting with Initials for Transparency) guidelines68. We also followed recommendations to maximise the indexing of titles, abstracts, and keywords in databases69.

Literature searches

We adapted methods from the previous version of the database on amphibian upper thermal limits1 to search the literature on thermal physiological traits. We aimed to compile a comprehensive and representative sample of the experimental literature on lower thermal limits and thermal preference in amphibians, complementing the data on upper thermal limits compiled previously (see1 for methods specific to upper thermal limits). PPottier accessed Scopus, ISI Web of Science (core collection), Lens, and ProQuest (dissertation & theses) on 01 November 2022 using The University of New South Wales’ institutional subscriptions. Briefly, the search strings were built using as a combination of relevant terms, including “temperature” (and synonyms) and “thermal tolerance or preference” (and synonyms) and “amphibian” (and synonyms) (see Table S1 for details). For studies in English, PPottier modified search strings to accommodate the structure of each database (Table S1) and performed backward searches of previously published reviews of amphibian thermal preference and tolerance1,4,5,6,10. This resulted in a total of 1676 unique documents. We limited the timespan of our searches to 31 May 2021 to match with the timespan represented in the upper thermal limit data1. This decision was made to normalise all searches to a single timespan to simplify future database updates. PPottier also performed Traditional and Simplified Chinese, French, Japanese, Portuguese, and Spanish searches in Google Scholar using search strings translated by native speakers (NR, PPottier, PPollo, SN, YY, and RRYO). The searches contained translated singular and plural forms of the following: “amphibian”, “frog”, “toad”, “salamander”, “newt”, “tadpole”, “preferred temperature”, “selected temperature”, “thermal preference”, “Tpref”, “Tsel”, or “CTmin”. Due to search string limitations in Google Scholar (256 characters), each term was assessed in its singular or plural form, and the search producing the largest number of results was selected. We performed searches following the format of (“preferred temperature” OR synonyms) AND (amphibian OR synonyms). We also performed separate searches with “CTmin” and (“Tpref” OR “Tsel”), as these terms are commonly used in the literature to refer to lower thermal limits and preferred temperatures. We (PPottier, NC) opted not to use “thermoregulation” as a synonym for “thermal preference” in our search strategy, as pilot searches revealed that this term often returned studies that did not present experimentally-derived thermal preference values, or studies that were already captured by the other search terms. PPottier used Publish or Perish70 to extract bibliographic records from Google Scholar. We also reused studies (designated with ** in Fig. 1) from non-English searches conducted in1 as the key terms used successfully retrieved results on cold tolerance. However, we limited the inclusion of studies to those meeting our first two criteria (i.e., studies on amphibians, and published in the targeted language) to reduce the volume of screening. We acknowledge that our searches do not encompass all languages relevant to amphibian thermal physiology research and invite speakers of languages not represented in the current version to contribute to future updates of the database.

PRISMA Flowchart delineating the databases used to retrieve studies on lower thermal limits and preferred body temperatures, the number of studies obtained at each stage of the screening process, and the reasons for excluding studies. * Two studies published in languages other than English (French, simplified Chinese) were retrieved through English searches. ** Studies from non-English searches done in Google Scholar from1. For the workflow used to obtain data on upper thermal limits, see1.

Eligibility criteria

We considered studies that empirically tested lower thermal limits or thermal preference in wild or laboratory amphibians. We included studies on larval, juvenile, metamorphic, and adult amphibians, and distinguished studies that acclimated both embryos and larvae to those acclimating single life stages. We excluded studies solely on embryonic stages due to the lack of comparable methods in embryos—for example, embryos are not capable of movement in a thermal gradient to assess thermal preference, and it is not possible to assess the righting response of embryos. For lower thermal limits, we included studies that measured critical thermal minimum (CTmin)71, median lethal temperature (LT50)72, or presented data that were convertible to these metrics (e.g., % survival of cohorts tested at different temperatures). We distinguish these metrics in the database. CTmin represents the temperature at which a specific physiological or behavioural endpoint is observed—such as the loss of righting response or a lack of response to prodding—when an organism is exposed to progressively decreasing temperatures (e.g., 1 °C/min). It does not represent the lowest temperature an organism can tolerate, but rather the onset of functional stasis, the point at which the organism is unable to move and incapable of essential survival behaviours such as thermoregulation or predator evasion71. This distinction is important, because many ectotherms can recover from temperatures below their CTmin. For instance, some species can recover from freezing to later resume normal function73. In contrast, LT50 is the temperature that is lethal to 50% of animals tested and is derived through statistical interpolation from survival rates across a range of temperatures72. For thermal preference, we included studies that empirically tested amphibian temperature selection in a thermal gradient or shuttlebox via measures of body temperature (or inferred body temperature from the position in the gradient or shuttlebox). We did not include data reported on amphibian body temperatures from uncontrolled (wild) conditions because available environmental temperatures were not standardised. We only included studies where thermal history (acclimatisation or acclimation temperature) was reported or could be inferred from the dates and coordinates of sampling. PPottier, RRO, PPollo, ANRV, YY, SV, AVL, and NC screened articles for eligibility using Rayyan QCRI74. This software facilitated the identification of key terms in titles, abstracts, and keywords to streamline the screening process for large volumes of literature. During data extraction, 47 papers were ultimately excluded for either lacking extractable data or for not complying with our inclusion criteria (43 English, 1 Traditional Chinese, 3 Simplified Chinese). A total of 184 studies were deemed eligible for inclusion in the database. Of these, 157 were identified through formal database searches (comprising one study published in simplified Chinese, and another study in French), while 20 non-English studies and an additional 7 English-language studies were retrieved through Google Scholar (Fig. 1). Therefore, nearly 15% (27/184) of the included studies were retrieved through non-English literature searches. Our literature search methods and screening process is summarised in a PRISMA flowchart75 (Fig. 1).

Data extraction

Data extractions were performed by PPottier (7.7% of estimates extracted), RRYO (6.7%), PPollo (5.3%), ANRV (6.2%), YY (3.0%), AVL (11.0%), SV (20.5%), and NC (45.0%). Note that these values do not add to 100% because some data entries were extracted by two authors. Data were extracted following the protocols described in the previous version of the database1. We extracted data directly from text and tables, and primarily used metaDigitise76 (version 1.0.1) in R77 to extract data presented in figures (although note that some authors have used WebPlotDigitizer78 (version 4.7)). When data were available in multiple formats (e.g., text and figure), we extracted it from the format with the highest resolution (e.g., data stratified by sex or location rather than aggregated across species). Where possible, we extracted measures of data dispersion (i.e. standard deviation, standard error) to accompany mean estimates. In cases where the raw data was available, we calculated summary statistics (means, standard deviation, sample size) to enhance the accuracy of the analysis. For studies reporting survival rates at different temperatures, we predicted the temperature at which 50% mortality occurred using logistic regression from the dose.p function from the MASS package79.

We also extracted all additional information presented in the studies to allow investigations of the sources of variation in the data and account for non-independence. We assigned identification numbers to each study, and assigned unique identifiers within each study for each estimate, species, population (individuals of the same species sampled from the same geographical location), and cohort (independent group of individuals within a study). Additional variables included sampling coordinates, acclimation temperatures, ramping rates, life stages, endpoints used to infer cold tolerance, or the duration of exposure to experimental treatments. Additional notes were also taken by each researcher extracting the data to facilitate technical validation. The full list of variables is described in the metadata. Species names were standardised during the extraction to match AmphibiaWeb80 and further standardised to match the most comprehensive phylogenetic tree to date81 (see Data Curation).

Data curation

To ensure consistency in data extraction across all studies, PPottier and NC extensively reviewed the extracted data to correct typological errors and resolve uncertainties identified during the extraction process. PPottier then curated the data in R77 (version 4.4.2), merging the newly extracted data with the previously compiled dataset from1. This process involved standardising publication information (publication year, source name) and other variables (e.g., geographical coordinates, IUCN threat status82) to ensure uniformity across both datasets. PPottier also standardised species names and taxonomy with phylogenetic information from81, which is primarily based on AmphibiaWeb80. The combined dataset comprises 324 publications35,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259,260,261,262,263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270,271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278,279,280,281,282,283,284,285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292,293,294,295,296,297,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312,313,314,315,316,317,318,319,320,321,322,323,324,325,326,327,328,329,330,331,332,333,334,335,336,337,338,339,340,341,342,343,344,345,346,347,348,349,350,351,352,353,354,355,356,357,358,359,360,361,362,363,364,365,366,367,368,369,370,371,372,373,374,375,376,377,378,379,380,381,382,383,384,385,386,387,388,389,390,391,392,393,394,395,396,397,398,399,400,401,402,403,404,405. Note that 53 of these publications were taken from university dissertations, and some of this work may have now been published e.g.406,407.

We also provide a curated version of the database (n = 4,401 estimates), where PPottier excluded data with procedural inconsistencies, incomplete species information (e.g., Hyloscirtus sp.), and studies involving animals exposed to toxicants, hormones, high levels of UV radiations, or infected with a pathogen. Procedural inconsistencies included traits measured on a single individual (n = 70 estimates), uncommon or inconsistent methodology (e.g., uncommon endpoint, n = 55), animals starved prior to testing (n = 34), animals that underwent surgery or amputation (n = 16), highly uncertain estimates (n = 14), animals dehydrated prior to testing (n = 14), animals exposed to hypoxic or hypercapnic conditions (n = 13), animals exposed to high levels of UV radiation (n = 5), animals perfused with pH solution (n = 3), estimates without sample sizes or metric of statistical dispersion (n = 3), and animals exposed to predators (n = 2). A script detailing the data curation steps is available at https://github.com/p-pottier/AmphiTherm. This data curation step removed 498 estimates from 15 studies and 45 species. However, we believe that this curated dataset offers broader usability. Nevertheless, we also provide the uncurated version of AmphiTherm for users interested in addressing more specific questions (e.g., how toxicants affect thermal tolerance and preference) or identifying existing research gaps within the field.

Data Records

The AmphiTherm database is stored at https://github.com/p-pottier/AmphiTherm, and regularly archived to Zenodo408. The repository is organised into four main folders: “data”, “R”, “references”, and “shiny_app”. These contain the metadata (.xlsx), raw, cleaned, and curated data (.csv), code for data curation and for producing the figures (.Rmd), code for deploying the Shiny web application (.R), supplementary data (.csv) and phylogenetic tree (.tre) for producing the figures, and bibliographic files (.ris and.bib) with all the references in the database. The metadata file describes all columns (n = 84) of the AmphiTherm database in detail. We have also launched a Shiny web application to help navigate and visualise the database. The Shiny app is available at https://p-pottier.shinyapps.io/AmphiTherm-Explorer/.

Data records are under a CC-BY license, enabling reuse with attribution. Therefore, database users must cite this study as well as the primary data sources to attribute the original authors and comply with copyright regulations.

We aim to conduct updates at regular five-year intervals, following the same systematic methods, to maintain the database as an up-to-date resource for amphibian thermal envelope data. We encourage researchers who possess relevant thermal data not included in the current version to contact us so that the database can be updated to continuously reflect the most comprehensive and current body of knowledge.

Data Overview

AmphiTherm encompasses 4,899 thermal physiological trait estimates, derived from 324 studies and covering 659 species across 38 families across a broad geographical coverage (Figs. 2, 3). This sample represents ~7.5% of all described amphibian species to date80 (Fig. 4). According to the IUCN red list82, most species (79.2%) are either not threatened or data-deficient (Fig. 2), yet 47 species are classified as near threatened (NC), 43 as vulnerable (VU), 29 as endangered (EN), 14 as critically endangered (CR), and one species now extinct. Considering that over 40% of amphibians are globally threatened22, this suggests that research on amphibian thermal physiology is predominantly conducted on non-threatened species, likely due to the invasive (or lethal) nature of some thermal tolerance experiments and the associated conservation concerns for threatened species. This database contains substantial within-species variation, with an average of 7.43 ± 19.5 (mean ± s.d.) estimates per species, spanning a range of 1 to 292 estimates, with species sampled from an average of 2.51 ± 3.29 populations. Approximately 81% of these estimates include a measure of statistical dispersion (standard deviation, standard error), facilitating their use in weighted (meta-)analyses409.

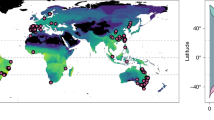

Geographic distribution of thermal tolerance and preference data. (a) World map showing the distribution of lower thermal limits (LTL), preferred body temperatures (PBT), and upper thermal limits (UTL) for anurans (circles) and salamanders (triangles). The shaded area represents the tropics. Note that coordinates were unavailable for 775 (15.8%) estimates. (b) Latitudinal distribution of estimates for LTL, PBT, and UTL. (c) Threat status of species, classified according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN82). One species (not displayed) is now extinct.

Distribution of mean estimates for three key thermal traits: lower thermal limits (inner heat map), thermal preference (central heat map), and upper thermal limits (outer heat map). The number of estimates for each species is displayed as histograms, scaled on a log2(x + 1) axis for clarity. The histograms are colour-coded according to the life stage assessed in the experiments, with the category “juveniles” comprising larvae, metamorphic, and juvenile stages. Gray colour represents missing data. The phylogeny relationships are based on the consensus tree from81. a. Notophthalmus viridescens, b. Dendropsophus ebraccatus, c. Hyla cinerea, d. Pleurodema thaul, e. Ceratophrys cranwelli, f. Craugastor longirostris, g. Rana pipiens, h. Xenopus laevis, i. Plethodon cylindraceus.

Distribution of thermal trait estimates across the phylogeny of most extant amphibians. Thermal limits and preferences are mapped onto a comprehensive phylogeny of 7,238 species (consensus tree, cf. 81) to identify taxonomic biases in existing knowledge. The outer circle presents family names, adapted from81.

This database update adds thermal data for 375 species, including lower thermal limits for 300 amphibian species and thermal preference data for 137 amphibian species (n = 1,825 estimates; Figs. 3, 4). The majority (98%) of lower thermal limit data are derived from CTmin estimates (990 estimates), with roughly 2% of estimates (19 estimates) derived from lethal limits (LT50). Thermal preference data represent 44% of the database update (816 estimates). This update has a relatively broad phylogenetic coverage, spanning 32 families, with 19.2% of records from salamanders (Figs. 3, 4).

Approximately 62.7% of this database is comprised of upper thermal limit estimates (3074 estimates from 616 species and 212 studies; Figs. 3, 4), highlighting a significant bias towards responses to heat extremes relative to lower thermal limits (1,009 estimates, 300 species, 88 studies) and thermal preferences (816 estimates, 137 species, 114 studies). We found that only 16 studies measured all three thermal traits, covering 59 species (~9% of the species in the dataset; Figs. 3, 4). Upper and lower thermal limits were studied more frequently in tandem (60 studies), allowing to calculate the thermal tolerance breadth (i.e., difference between upper and lower thermal limits) of 276 species (~42% of the species in the dataset; Figs. 3, 4).

Geographically, data were collected on all continents where amphibians occur yet exhibit a strong bias towards Nearctic and European regions (Fig. 2). Large geographic gaps in thermal data are evident across Africa, most regions of Asia, Western Australia, and central South America—regions that are biodiversity hotspots for amphibians (Fig. 2). This is particularly concerning as they constrain our understanding of how species from these underrepresented yet extremely diverse regions410 might respond to climate change. We also identified taxonomic gaps in existing sampling where an entire order of amphibians, Gymnophiona, remained unrepresented in the database (Fig. 4). In addition, 1 of 10 families of Caudata and 7 of 36 families of Anura lack thermal limits or preferred body temperature estimates (Fig. 4). This suggests that further efforts are needed to broaden the research scope and better represent the thermal niche of amphibians.

We found that the majority (88.7%) of the literature on amphibian thermal physiological traits was published in English (4,343 estimates). However, non-English language literature contributes a notable and important portion of the knowledge base, accounting for approximately 11.3% of the data. Notably, this includes 289 estimates from publications in traditional Chinese (23 species, 7 studies), 131 estimates from Spanish (40 species, 11 studies), 82 estimates from simplified Chinese (12 species, 10 studies), 28 estimates from Portuguese (10 species, 3 studies), and 26 estimates from French publications (4 species, 3 studies). Including more languages, such as Afrikaans, Arabic, Bengali, Dutch, German, Hindu-Urdu, Korean, Russian, or Swahili in the screening process may help fill some gaps in future updates to the database411. Given the historical bias of higher impact publishing outlets against studies on herpetofauna412, there are likely a number of studies in non-indexed journals or regional journals in local languages that were not retrieved using our methods.

Technical Validation

We employed a transparent and reproducible workflow to systematically review over 4,000 studies from five databases and across seven languages. The potential limitations of this database are similar to those described in1. First, the methods used for indexing and retrieving studies in Google Scholar are not publicly disclosed413, which may undermine reproducibility. However, given the limited coverage of non-English studies in other databases (with 95% and 93% of references in Scopus and Web of Science indexed in English, respectively), Google Scholar remains one of the most suitable tools to synthesise across multiple non-English languages at present414,415. Second, different authors extracted data from the original studies, introducing the possibility of individual errors. To ensure consistency and accuracy, all extracted data were subsequently cross-checked and standardised by NC and PPottier (see Data Curation) to minimise the risk of bias and strengthen the reliability of the dataset.

Usage Notes

We anticipate that this database will facilitate a wide range of novel analyses and investigations that may be difficult to foresee at this time, but we are excited to see how these data advance research in amphibian biology and conservation. Our recommendations for using this resource are straightforward: we encourage researchers to have strong foundations in thermal ecology and amphibian biology, and to carefully consider the best approaches for integrating these data into their own investigations.

The database represents a comprehensive compilation of studies employing diverse approaches and experimental designs. Given that we cannot anticipate the full scope of research applications, we have made the entire dataset available to allow users to filter and customise the data as needed. We strongly encourage users to clearly document their analytical steps to ensure reproducibility. However, we emphasise that this database version includes data from animals tested under atypical conditions (e.g., amputations, chemical exposure), or from experiments without replication (e.g. data from a single individual). To accommodate most research needs, we therefore also provide a curated version of the database where we excluded data with procedural inconsistencies, incomplete species-level information, and data involving animals exposed to toxicants, hormones, excessive UV radiation, or pathogens. This curated version of the database is likely more suited for research in ecophysiology, though users with more specialised research questions may find value in the complete dataset. Scripts detailing the data cleaning and curation processes are available at https://github.com/p-pottier/AmphiTherm and should provide further guidance for researchers in tailoring the dataset to their specific research needs. We also provide a Shiny web application (https://p-pottier.shinyapps.io/AmphiTherm-Explorer/) to facilitate data exploration and filtering.

As described in the first iteration of this database1, the data contain inherent sources of non-independence as multiple estimates were extracted from each study, species, population (multiple sampling locations from each species), and cohort (e.g., repeated measures on the same individuals). We recommend that users use phylogenetically-informed statistical models with hierarchical random-effect structures to account for and partition sources of variation408,416. Users should also account for variations in sampling effort (sample size differences), for instance, by weighting estimates by the inverse of their sampling variance408. Employing hierarchical models that incorporate sampling variance can help address issues of biological and methodological non-independence, enabling more accurate inferences of the factors driving variation in the data408. Most (81%) estimates are associated with a measure of dispersion (standard deviation or standard error), species information is standardised to published phylogenetic information81, and unique identifiers have been assigned to each study, species, population, and cohort. These features make AmphiTherm readily applicable for use in complex statistical models aimed at uncovering the drivers of thermal tolerance and preferences in amphibians.

As described in previous studies, thermal traits in amphibians are influenced by multiple variables, including acclimation temperature, acclimation time, ramping rate, endpoint metrics, body size, sex, assay duration, and geographic origin, among others8,20,21. We recommend careful attention to these variables, with consideration of incorporating sources of methodological or biological variation as covariates in statistical models, to better capture the complexities of amphibian thermal ecology. Finally, it is important to note that due to the data gaps in hotspots of amphibian diversity, the data herein represent only a subset of total amphibian diversity, and subsequent analyses should acknowledge this limitation. Formally assessing the extent to which geographic and taxonomic biases may influence ecological inferences is an important avenue for research.

Data availability

All data and materials needed to reproduce this study are available at https://github.com/p-pottier/AmphiTherm, which is archived permanently in Zenodo408.

Code availability

The code used to process the data and produce the figures for this manuscript is available at https://github.com/p-pottier/AmphiTherm, which is archived permanently in Zenodo408.

References

Pottier, P. et al. A comprehensive database of amphibian heat tolerance. Sci. Data 9, 600 (2022).

Pinsky, M. L., Eikeset, A. M., McCauley, D. J., Payne, J. L. & Sunday, J. M. Greater vulnerability to warming of marine versus terrestrial ectotherms. Nature 569, 108–111 (2019).

Morley, S. A., Peck, L. S., Sunday, J. M., Heiser, S. & Bates, A. E. Physiological acclimation and persistence of ectothermic species under extreme heat events. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 28, 1018–1037 (2019).

Navas, C. A., Gouveia, S. F., Solano-Iguarán, J. J., Vidal, M. A. & Bacigalupe, L. D. Amphibian responses in experimental thermal gradients: Concepts and limits for inference. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 254, 110576 (2021).

Leiva, F. P., Calosi, P. & Verberk, W. C. E. P. Scaling of thermal tolerance with body mass and genome size in ectotherms: a comparison between water- and air-breathers. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20190035 (2019).

Bennett, J. M. et al. GlobTherm, a global database on thermal tolerances for aquatic and terrestrial organisms. Sci. Data 5, 180022 (2018).

Rohr, J. R. et al. The complex drivers of thermal acclimation and breadth in ectotherms. Ecol. Lett. 21, 1425–1439 (2018).

DuBose, T. P. et al. Thermal Traits of Anurans Database for the Southeastern United States (TRAD): A Database of Thermal Trait Values for 40 Anuran Species. Ichthyol. Herpetol. 112, 21–30 (2024).

Bayat, H. S. et al. Global thermal tolerance of freshwater invertebrates and fish. Sci Data 12, 1488 (2025).

Gunderson, A. R. & Stillman, J. H. Plasticity in thermal tolerance has limited potential to buffer ectotherms from global warming. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20150401 (2015).

Urban, M. C. Accelerating extinction risk from climate change. Science 348, 571–573 (2015).

Wiens, J. J. Climate-Related Local Extinctions Are Already Widespread among Plant and Animal Species. PLoS Biol. 14, e2001104 (2016).

Carey, C. & Alexander, M. A. Climate change and amphibian declines: is there a link? Divers. Distrib. 9, 111–121 (2003).

Sinervo, B. et al. Erosion of Lizard Diversity by Climate Change and Altered Thermal Niches. Science 328, 894–899 (2010).

Anderson, R. O., Meiri, S. & Chapple, D. G. The biogeography of warming tolerance in lizards. J. Biogeogr. 49, 1274–1285 (2022).

Biber, M. F., Voskamp, A. & Hof, C. Potential effects of future climate change on global reptile distributions and diversity. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 32, 519–534 (2023).

Pottier, P. et al. Vulnerability of amphibians to global warming. Nature 954–961 (2025).

Turner, M. G. et al. Climate change, ecosystems and abrupt change: science priorities. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 375, 20190105 (2020).

Walsh, J. E. et al. Extreme weather and climate events in northern areas: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 209, 103324 (2020).

Bodensteiner, B. L. et al. Thermal adaptation revisited: How conserved are thermal traits of reptiles and amphibians? J. Exp. Zool. A 335, 173–194 (2021).

Taylor, E. N. et al. The thermal ecology and physiology of reptiles and amphibians: A user’s guide. J. Exp. Zool. A 335, 13–44 (2021).

Luedtke, J. A. et al. Ongoing declines for the world’s amphibians in the face of emerging threats. Nature 622, 308–314 (2023).

Hatch, K. A. & Kroft, K. L. Winterkill in Lotic Systems May Be an Important Driver of Amphibian Population Declines. Ichthyol. Herpetol. 110, 575–584 (2022).

Enriquez-Urzelai, U., Kearney, M. R., Nicieza, A. G. & Tingley, R. Integrating mechanistic and correlative niche models to unravel range-limiting processes in a temperate amphibian. Global Change Biol. 25, 2633–2647 (2019).

Huey, R. B. & Slatkin, M. Cost and Benefits of Lizard Thermoregulation. Q. Rev. Biol. (1976).

Dawson, W. R. On the Physiological Significance of the Preferred Body Temperatures of Reptiles. In: Gates, D. M. & Schmerl, R. B. (eds) Perspectives of Biophysical Ecology, 443–473 (Springer, 1975).

Buckley, L. B. Linking Traits to Energetics and Population Dynamics to Predict Lizard Ranges in Changing Environments. Am. Nat. 171, E1–E19 (2008).

Buckley, L. B. et al. Can mechanism inform species’ distribution models? Ecol. Lett. 13, 1041–1054 (2010).

Clusella-Trullas, S., Blackburn, T. M. & Chown, S. L. Climatic Predictors of Temperature Performance Curve Parameters in Ectotherms Imply Complex Responses to Climate Change. Am. Nat. 177, 738–751 (2011).

Caetano, G. H. O. et al. Time of activity is a better predictor of the distribution of a tropical lizard than pure environmental temperatures. Oikos 129, 953–963 (2020).

Claunch, N. M. et al. Commonly collected thermal performance data can inform species distributions in a data-limited invader. Sci. Rep. 13, 15880 (2023).

Ivey, K. et al. Temperature-based activity estimation accurately predicts surface activity, but not microhabitat use, in the endangered heliothermic lizard Gambelia sila. Amphib. Reptile Conserv. 16, 10 (2022).

Üveges, B. et al. Experimental evidence for beneficial effects of projected climate change on hibernating amphibians. Sci. Rep. 6, 26754 (2016).

Rollins-Smith, L. A. Amphibian immunity–stress, disease, and climate change. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 66, 111–119 (2017).

Beukema, W. et al. Microclimate limits thermal behaviour favourable to disease control in a nocturnal amphibian. Ecol. Lett. 24, 27–37 (2021).

Waddle, A. W. et al. Hotspot shelters stimulate frog resistance to chytridiomycosis. Nature 631, 344–349 (2024).

Greenspan, S. E. et al. Warming drives ecological community changes linked to host-associated microbiome dysbiosis. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 1057–1061 (2020).

Zhu, L. et al. Environmental Temperatures Affect the Gastrointestinal Microbes of the Chinese Giant Salamander. Front. Microbiol. 12 (2021).

Robak, M. J., Saenz, V., de Cortie, E. & Richards-Zawacki, C. L. Effects of temperature on the interaction between amphibian skin bacteria and Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Front. Microbiol. 14 (2023).

Sunday, J. M., Bates, A. E. & Dulvy, N. K. Thermal tolerance and the global redistribution of animals. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 686–690 (2012).

Moore, N. A. et al. Temperate species underfill their tropical thermal potentials on land. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1993–2003 (2023).

Bennett, J. M. et al. The evolution of critical thermal limits of life on Earth. Nat. Commun. 12, 1198 (2021).

Harishchandra, A., Xue, H., Salinas, S. & Jayasundara, N. Thermal physiology integrated species distribution model predicts profound habitat fragmentation for estuarine fish with ocean warming. Sci. Rep. 12, 21781 (2022).

Zlotnick, O. B., Musselman, K. N. & Levy, O. Deforestation poses deleterious effects to tree-climbing species under climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 289–295 (2024).

Stark, G., Ma, L., Zeng, Z.-G., Du, W.-G. & Levy, O. Cool shade and not-so-cool shade: How habitat loss may accelerate thermal stress under current and future climate. Global Change Biol. 29, 6201–6216 (2023).

Briscoe, N. J. et al. Mechanistic forecasts of species responses to climate change: The promise of biophysical ecology. Global Change Biol. 29, 1451–1470 (2023).

Kearney, M. et al. Modelling species distributions without using species distributions: the cane toad in Australia under current and future climates. Ecography 31, 423–434 (2008).

Araújo, M. B. et al. Heat freezes niche evolution. Ecol. Lett. 16, 1206–1219 (2013).

Hoffmann, A. A., Chown, S. L. & Clusella-Trullas, S. Upper thermal limits in terrestrial ectotherms: how constrained are they? Funct. Ecol. 27, 934–949 (2013).

Chown, S. L. Physiological variation in insects: hierarchical levels and implications. J. Insect Physiol. 47, 649–660 (2001).

Rubalcaba, J. G., Gouveia, S. F., Villalobos, F., Olalla-Tárraga, M. Á. & Sunday, J. Climate drives global functional trait variation in lizards. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 524–534 (2023).

Longo, A. V. & Zamudio, K. R. Temperature variation, bacterial diversity and fungal infection dynamics in the amphibian skin. Mol. Ecol. 26, 4787–4797 (2017).

Xu, L. et al. The Behavior of Amphibians Shapes Their Symbiotic Microbiomes. mSystems 5, e00626–20 (2020).

Bernardo-Cravo, A. P., Schmeller, D. S., Chatzinotas, A., Vredenburg, V. T. & Loyau, A. Environmental Factors and Host Microbiomes Shape Host–Pathogen Dynamics. Trends Parasitol. 36, 616–633 (2020).

Sonn, J. M., Porter, W. P., Mathewson, P. D. & Richards-Zawacki, C. L. Predictions of Disease Risk in Space and Time Based on the Thermal Physiology of an Amphibian Host-Pathogen Interaction. Front. Ecol. Evol. 8 (2020).

Neely, W. J. et al. Synergistic effects of warming and disease linked to high mortality in cool-adapted terrestrial frogs. Biol. Conserv. 245, 108521 (2020).

Fontaine, S. S., Mineo, P. M. & Kohl, K. D. Experimental manipulation of microbiota reduces host thermal tolerance and fitness under heat stress in a vertebrate ectotherm. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 405–417 (2022).

Crump, P. & Grow, S. Action plan for ex situ amphibian conservation in the AZA community. Association of Zoos & Aquariums, Amphibian Taxon Advisory Group (2007).

Beaupre, S., Jacobson, E., Lillywhite, H. & Zamudio, K. Guidelines for use of live amphibians and reptiles in field and laboratory research (2004).

Poole, V. A. & Grow, S. Amphibian Husbandry Resource Guide, Edition 2.0. (Association of Zoos & Aquariums, Silver Spring, Maryland, USA, 2017).

Pough, H. F. Amphibian biology and husbandry. ILAR J. 48, 203–213 (2007).

ASIH (American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists). Guidelines for Use of Live Amphibians and Reptiles in Field and Laboratory Research. (Lawrence, 2004).

Linhoff, L. J. & Donnelly, M. A. Assessing release strategies for reintroductions of endangered Wyoming toads. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 46, e1341 (2022).

Klocke, B. et al. Movement and survival of captive-bred Limosa harlequin frogs (Atelopus limosus) released into the wild. Front. Amphib. Reptile Sci. 1 (2023).

Greenspan, S. E. et al. Realistic heat pulses protect frogs from disease under simulated rainforest frog thermal regimes. Funct. Ecol. 31, 2274–2286 (2017).

Sinervo, B. et al. Climate change and collapsing thermal niches of desert reptiles and amphibians: Assisted migration and acclimation rescue from extirpation. Sci. Total Environ. 908, 168431 (2024).

McNutt, M. K. et al. Transparency in authors’ contributions and responsibilities to promote integrity in scientific publication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 2557–2560 (2018).

Nakagawa, S. et al. Method Reporting with Initials for Transparency (MeRIT) promotes more granularity and accountability for author contributions. Nat. Commun. 14, 1788 (2023).

Pottier, P. et al. Title, abstract and keywords: a practical guide to maximize the visibility and impact of academic papers. Proc. R. Soc. B 291, 20241222 (2024).

Harzing, A. Publish or perish (2007).

Cowles, R. B. & Bogert, C. M. A preliminary study of the thermal requirements of desert reptiles. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 83, 261–296 (1944).

Fry, F. E. J. Effects of the environment on animal activity. Publ. Ont. Fish. Res. Lab. 55, 1–62 (1947).

Costanzo, J. P., Reynolds, A. M., Amaral, M. C. Fdo, Rosendale, A. J. & Lee, R. E. Jr. Cryoprotectants and Extreme Freeze Tolerance in a Subarctic Population of the Wood Frog. PLoS ONE 10, e0117234 (2015).

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z. & Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5, 210 (2016).

O’Dea, R. E. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses in ecology and evolutionary biology: a PRISMA extension. Biol. Rev. 96, 1695–1722 (2021).

Pick, J. L., Nakagawa, S. & Noble, D. W. A. Reproducible, flexible and high-throughput data extraction from primary literature: The metaDigitise r package. Methods Ecol. Evol. 10, 426–431 (2019).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2019).

Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer (2024).

Ripley, B. et al. Package ‘mass’. CRAN R 538, 822 (2013).

AmphibiaWeb. https://amphibiaweb.org. University of California, Berkeley, California, USA (2025).

Jetz, W. & Pyron, R. A. The interplay of past diversification and evolutionary isolation with present imperilment across the amphibian tree of life. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 850–858 (2018).

IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (2021).

Agudelo-Cantero, G. A. & Navas, C. A. Interactive effects of experimental heating rates, ontogeny and body mass on the upper thermal limits of anuran larvae. J. Therm. Biol. 82, 43–51 (2019).

Alveal, N. et al. Relationship between thermal behavior and sex of a population of Pleurodema thaul (Amphibia: Leiuperidae) of the commune of Antuco, Biobío region. Gayana (Concepción) 83, 93–101 (2019).

Alveal Riquelme, N. Relaciones entre la fisiología térmica y las características bioclimáticas de Rhinella spinulosa (Anura: Bufonidae) en Chile a través del enlace mecanicista de nicho …. (Universidad de Concepción, 2015).

Alves, M. Tolerância térmica em espécies de anuros neotropicais do gênero Dendropsophus Fitzinger, 1843 e efeito da temperatura na resposta à predação. (Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, 2016).

Anderson, R. C. O. & Andrade, D. V. Trading heat and hops for water: Dehydration effects on locomotor performance, thermal limits, and thermoregulatory behavior of a terrestrial toad. Ecol. Evol. 7, 9066–9075 (2017).

Aponte Gutiérrez, A. Endurecimiento térmico en Pristimantis medemi (Anura: Craugastoridae), en coberturas boscosas del Municipio de Villavicencio (Meta). (Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2020).

Arrigada García, K. Conductas térmica en dos poblaciones de Batrachyla taeniata provenientes de la localidad de Ucúquer en la región de O’Higgins y de la localidad de Hualpén en la …. (Universidad de Concepción, 2019).

Azambuja, G., Martins, I. K., Franco, J. L. & Santos, T. G. dos. Effects of mancozeb on heat Shock protein 70 (HSP70) and its relationship with the thermal physiology of Physalaemus henselii tadpoles (Anura: Leptodactylidae). J. Therm. Biol. 98, 102911 (2021).

Bacigalupe, L. D. et al. Natural selection on plasticity of thermal traits in a highly seasonal environment. Evol. Appl. 11, 2004–2013 (2018).

Bakewell, L., Kelehear, C. & Graham, S. P. Impacts of temperature on immune performance in a desert anuran (Anaxyrus punctatus). J. Zool. 315, 49–57 (2021).

Balogová, M. & Gvoždík, L. Can Newts Cope with the Heat? Disparate Thermoregulatory Strategies of Two Sympatric Species in Water. PLoS ONE 10, e0128155 (2015).

Barria, A. M. & Bacigalupe, L. D. Intraspecific geographic variation in thermal limits and acclimatory capacity in a wide distributed endemic frog. J. Therm. Biol. 69, 254–260 (2017).

Bazin, Y., Wharton, D. A. & Bishop, P. J. Cold tolerance and overwintering of an introduced New Zealand frog, the brown tree frog (Litoria ewingii). Cryo Lett. 28, 347–358 (2007).

Beltrán, I., Ramírez-Castañeda, V., Rodríguez-López, C., Lasso, E. & Amézquita, A. Dealing with hot rocky environments: critical thermal maxima and locomotor performance in Leptodactylus lithonaetes (Anura: Leptodactylidae). Herpetol. J. 29, 155–161 (2019).

Berkhouse, C. & Fries, J. Critical thermal maxima of juvenile and adult San Marcos salamanders (Eurycea nana). Southwest. Nat. 40, 430–434 (1995).

Berman, D. I., Meshcheryakova, E. N. & Bulakhova, N. A. The Japanese tree frog (Hyla japonica), one of the most cold-resistant species of amphibians. Dokl. Biol. Sci. 471, 276–279 (2016).

Berman, D. I., Bulakhova, N. A., Meshcheryakova, E. N. & Shekhovtsov, S. V. Overwintering and cold tolerance in the Moor Frog (Rana arvalis) across its range. Can. J. Zool. 98, 705–714 (2020).

Bernal Castro, E. A. Influence of environment on thermal ecology of direct-developing frogs (Anura: Craugastoridae: Pristimantis) in the eastern Andes of Colombia. (Universidad de los Andes, 2019).

Berner, N. J. & Puckett, R. E. Phenotypic flexibility and thermoregulatory behavior in the eastern red-spotted newt (Notophthalmus viridescens viridescens). J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Genet. Physiol. 313, 231–239 (2010).

Bicego, K. C. & Branco, L. G. S. Discrete electrolytic lesion of the preoptic area prevents LPS-induced behavioral fever in toads. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 3513–3518 (2002).

Bicego-Nahas, K. C., Steiner, A. A., Carnio, E. C., Antunes-Rodrigues, J. & Branco, L. G. S. Antipyretic effect of arginine vasotocin in toads. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 278, R1408–R1414 (2000).

Bícego-Nahas, K. C., Gargaglioni, L. H. & Branco, L. G. S. Seasonal changes in the preferred body temperature, cardiovascular, and respiratory responses to hypoxia in the toad, Bufo paracnemis. J. Exp. Zool. 289, 359–365 (2001).

Blem, C. R., Ragan, C. A. & Scott, L. S. The thermal physiology of two sympatric treefrogs Hyla cinerea and Hyla chrysoscelis (Anura; Hylidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 85, 563–570 (1986).

Bliss, M. M. & Cecala, K. K. Terrestrial Salamanders Alter Antipredator Behavior Thresholds Following Tail Autotomy. Herpetologica 73, 94–99 (2017).

Bonino, M. F., Cruz, F. B. & Perotti, M. G. Does temperature at local scale explain thermal biology patterns of temperate tadpoles? J. Therm. Biol. 94 (2020).

Bovo, R. P. Fisiologia térmica e balanço hídrico em anfíbios anuros. (Universidad Estadual Paulista, 2015).

Branco, L. G. Effects of 2-deoxy-D-glucose and insulin on plasma glucose levels and behavioral thermoregulation of toads. Am. J. Physiol. 272, R1–R5 (1997).

Branco, L. G. & Malvin, G. M. Thermoregulatory effects of cyanide and azide in the toad, Bufo marinus. Am. J. Physiol. 270, R169–173 (1996).

Branco, L. G., Steiner, A. A., Tattersall, G. J. & Wood, S. C. Role of adenosine in the hypoxia-induced hypothermia of toads. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 279, R196–201 (2000).

Branco, L. G. & Wood, S. C. Role of central chemoreceptors in behavioral thermoregulation of the toad, Bufo marinus. Am. J. Physiol. 266, R1483–1487 (1994).

Branco, L. G. S. & Steiner, A. A. Central thermoregulatory effects of lactate in the toad Bufo paracnemis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 122, 457–461 (1999).

Brattstrom, B. H. Thermal acclimation in Australian amphibians. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 35, 69–103 (1970).

Brattstrom, B. H. & Regal, P. Rate of thermal acclimation in the Mexican salamander Chiropterotriton. Copeia 1965, 514–515 (1965).

Brattstrom, B. H. A Preliminary Review of the Thermal Requirements of Amphibians. Ecology 44, 238–255 (1963).

Brattstrom, B. H. Thermal acclimation in Anuran amphibians as a function of latitude and altitude. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 24, 93–111 (1968).

Brattstrom, B. H. & Lawrence, P. The Rate of Thermal Acclimation in Anuran Amphibians. Physiol. Zool. 35, 148–156 (1962).

Brown, H. A. The heat resistance of some anuran tadpoles (Hylidae and Pelobatidae). Copeia 1969, 138 (1969).

Burke, E. M. & Pough, F. H. The role of fatigue in temperature resistance of salamanders. J. Therm. Biol. 1, 163–167 (1976).

Burrowes, P. A., Navas, C. A., Jiménez-Robles, O., Delgado, P. & De La Riva, I. Climatic heterogeneity in the Bolivian Andes: Are frogs trapped? South Am. J. Herpetol. 18, 1–12 (2020).

Bury, R. B. Low thermal tolerances of stream amphibians in the Pacific Northwest: Implications for riparian and forest management. Appl. Herpetol. 5, 63–74 (2008).

Carey, C. Factors affecting body temperatures of toads. Oecologia 35, 197–219 (1978).

Carvajalino-Fernández, J. M., Gomez, M. A. B., Giraldo-Gutierréz, L. & Navas, C. A. Freeze tolerance in neotropical frogs: an intrageneric comparison using Pristimantis species of high elevation and medium elevation. J. Trop. Ecol. 37, 118–125 (2021).

Castellanos García, L. A. Days of futures past: integrating physiology, microenvironments, and biogeographic history to predict response of frogs in neotropical dry-forest to global warming. (Universidad de los Andes, 2017).

Catenazzi, A., Lehr, E. & Vredenburg, V. T. Thermal physiology, disease, and amphibian declines on the eastern slopes of the Andes. Conserv. Biol. 28, 509–517 (2014).

Cecala, K. K., Noggle, W. & Burns, S. Negative Phototaxis Results from Avoidance of Light and Temperature in Stream Salamander Larvae. J. Herpetol. 51, 263–269 (2017).

Chang, L.-W. Heat tolerance and its plasticity in larval Bufo bankorensis from different altitudes. (National Cheng Kung University, 2002).

Chavez Landi, P. A. Fisiología térmica de un depredador Dasythemis sp.(Odonata: Libellulidae) y su presa Hypsiboas pellucens (Anura: Hylidae) y sus posibles implicaciones frente al …. (Pontificia Universidad Católica Del Ecuador, 2017).

Chen, T.-C., Kam, Y.-C. & Lin, Y.-S. Thermal physiology and reproductive phenology of Buergeria japonica (Rhacophoridae) breeding in a stream and a geothermal hot spring in Taiwan. Zool. Sci. 18, 591–596 (2001).

Cheng, C.-B. A study of warming tolerance and thermal acclimation capacity of tadpoles in Taiwan. (Tunghai University 2017).

Cheng, Y.-J. Effect of salinity on the critical thermal maximum of tadpoles living in brackish water. (Tunghai University 2017).

Christian, K. A., Nunez, F., Clos, L. & Diaz, L. Thermal relations of some tropical frogs along an altitudinal gradient. Biotropica 20, 236–239 (1988).

Churchill, T. A. & Storey, K. B. Dehydration tolerance in wood frogs: a new perspective on development of amphibian freeze tolerance. Am. J. Physiol. 265, R1324–1332 (1993).

Claussen, D. L. The thermal relations of the tailed frog, Ascaphus truei, and the pacific treefrog, Hyla regilla. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 44, 137–153 (1973).

Claussen, D. L. Thermal acclimation in ambystomatid salamanders. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 58, 333–340 (1977).

Clemente, A. C. Resposta termofílica pós-prandial do sapo-cururu, Rhinella diptycha. (UNESP 2019).

Cohen, J. M. et al. The thermal mismatch hypothesis explains host susceptibility to an emerging infectious disease. Ecol. Lett. 20, 184–193 (2017).

Contreras Cisneros, J. Temperatura crítica máxima, tolerancia al frío y termopreferendum del tritón del Montseny (Calotriton arnoldii). (Universitat de Barcelona 2019).

Contreras López, J. M. Requerimientos térmicos de Craugastor loki (Anura: Craugastoridae) en la Sierra Madre de Chiapas, México. (Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas 2021).

Contreras Oñate, S. Posible efecto de las temperaturas de aclimatación sobre las respuestas térmicas en temperaturas críticas máximas (TCmás) y mínimas (TCmín) de una población de …. (Universidad de Concepción 2016).

Cooper, R. D. & Shaffer, H. B. Allele-specific expression and gene regulation help explain transgressive thermal tolerance in non-native hybrids of the endangered California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense). Mol. Ecol. 30, 987–1004 (2021).

Cortes, P. A., Puschel, H., Acuña, P., Bartheld, J. L. & Bozinovic, F. Thermal ecological physiology of native and invasive frog species: do invaders perform better? Conserv. Physiol. 4, cow056 (2016).

Crawshaw, L. I., Rausch, R. N., Wollmuth, L. P. & Bauer, E. J. Seasonal Rhythms of Development and Temperature Selection in Larval Bullfrogs, Rana catesbeiana Shaw. Physiol. Zool. 65, 346–359 (1992).

Crow, J. C., Forstner, M. R. J., Ostr, K. G. & Tomasso, J. R. The role of temperature on survival and growth of the Barton Springs salamander (Eurycea sosorum). Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 11, 328–334 (2016).

Cupp, P. V. Thermal Tolerance of Five Salientian Amphibians during Development and Metamorphosis. Herpetologica 36, 234–244 (1980).

Dabruzzi, T. F., Wygoda, M. L. & Bennett, W. A. Some Like it Hot: Heat Tolerance of the Crab-Eating Frog, Fejervarya cancrivora. Micronesica 43, 101–106 (2012).

Dainton, B. H. Heat tolerance and thyroid activity in developing tadpoles and juvenile adults of Xenopus laevis (Daudin). J. Therm. Biol. 16, 273–276 (1991).

Daniel, N. J. J. Impact of climate change on Singapore amphibians. (National University of Singapore 2013).

Davies, S. J., McGeoch, M. A. & Clusella-Trullas, S. Plasticity of thermal tolerance and metabolism but not water loss in an invasive reed frog. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 189, 11–20 (2015).

de Oliviera Anderson, R. C., Bovo, R. P. & Andrade, D. V. Seasonal variation in the thermal biology of a terrestrial toad, Rhinella icterica (Bufonidae), from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. J. Therm. Biol. 74, 77–83 (2018).

de Vlaming, V. L. & Bury, R. B. Thermal Selection in Tadpoles of the Tailed-Frog, Ascaphus truei. J. Herpetol. 4, 179–189 (1970).

Delgado-Suazo, P. & Burrowes, P. A. Response to thermal and hydric regimes point to differential inter- and intraspecific vulnerability of tropical amphibians to climate warming. J. Therm. Biol. 103, 103148 (2022).

Delson, J. & Whitford, W. G. Critical Thermal Maxima in Several Life History Stages in Desert and Montane Populations of Ambystoma tigrinum. Herpetologica 29, 352–355 (1973).

Dohm, M. R., Mautz, W. J., Looby, P. G., Gellert, K. S. & Andrade, J. A. Effects of Ozone on Evaporative Water Loss and Thermoregulatory Behavior of Marine Toads (Bufo marinus). Environ. Res. 86, 274–286 (2001).

Drakulić, S. et al. Local differences of thermal preferences in European common frog (Rana temporaria) tadpoles. Zool. Anz. 268, 47–54 (2017).

Duarte, H. et al. Can amphibians take the heat? Vulnerability to climate warming in subtropical and temperate larval amphibian communities. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 412–421 (2012).

Duarte, H. S. A comparative study of the thermal tolerance of tadpoles of Iberian anurans. (Universidade de Lisboa 2011).

Duclaux, R., Fantino, M. & Cabanac, M. Comportement thermoregulateur chez Rana esculenta. Pflugers Arch. 342, 347–358 (1973).

Dunlap, D. Evidence for a daily rhythm of heat resistance in cricket frogs, Acris crepitans. Copeia 852 (1969).

Dunlap, D. G. Critical Thermal Maximum as a Function of Temperature of Acclimation in Two Species of Hylid Frogs. Physiol. Zool. 41, 432–439 (1968).

Easton, L. Determining the feasibility of a translocation by investigating the ecology and physiology of the threatened Hochstetter’s frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri). (University of Otago 2015).

Elwood, J. R. L. Variation in hsp70 levels and thermotolerance among terrestrial salamanders of the Plethodon glutinosus complex. (Drexel University 2003).

Enriquez-Urzelai, U. et al. Ontogenetic reduction in thermal tolerance is not alleviated by earlier developmental acclimation in Rana temporaria. Oecologia 189, 385–394 (2019).

Enriquez-Urzelai, U. et al. The roles of acclimation and behaviour in buffering climate change impacts along elevational gradients. J. Anim. Ecol. 89, 1722–1734 (2020).

Enriquez‐Urzelai, U., Palacio, A. S., Merino, N. M., Sacco, M. & Nicieza, A. G. Hindered and constrained: limited potential for thermal adaptation in post‐metamorphic and adult Rana temporaria along elevational gradients. J. Evol. Biol. 31, 1852–1862 (2018).

Erskine, D. J. & Hutchison, V. H. Reduced thermal tolerance in an amphibian treated with melatonin. J. Therm. Biol. 7, 121–123 (1982).

Escobar Serrano, D. Acclimation scope of the critical thermal limits in Agalychnis spurrelli (Hylidae) and Gastrotheca pseustes (Hemiphractidae) and their implications under climate change scenarios. (Pontificia Universidad Católica Del Ecuador 2016).

Familiar Lopez, M. Distribution, Ecology, Disease and Physiology of a Mountain-Top Endemic Frog in the Face of Climate Change: A Study on Philoria loveridgei. (Griffith University 2016).

Fan, X., Lei, H. & Lin, Z. Ontogenetic shifts in selected body temperature and thermal tolerance of the tiger frog, Hoplobatrachus chinensis. Acta Ecol. Sin. 32, 5574–5580 (2012).

Fan, X. L., Lin, Z. H. & Scheffers, B. R. Physiological, developmental, and behavioral plasticity in response to thermal acclimation. J. Therm. Biol. 97 (2021).

Fernández-Loras, A. et al. Infection with Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis lowers heat tolerance of tadpole hosts and cannot be cleared by brief exposure to CTmax. PLoS ONE 14 (2019).

Finnerty, P. B., Shine, R. & Brown, G. P. Survival of the feces: Does a nematode lungworm adaptively manipulate the behavior of its cane toad host? Ecol. Evol. 8, 4606–4618 (2018).

Floyd, R. B. Ontogenetic change in the temperature tolerance of larval Bufo marinus (Anura: Bufonidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 75, 267–271 (1983).

Floyd, R. B. Variation in Temperature Preference with Stage of Development of Bufo marinus Larvae. J. Herpetol. 18, 153–158 (1984).

Floyd, R. B. Effects of Photoperiod and Starvation on the Temperature Tolerance of Larvae of the Giant Toad, Bufo marinus. Copeia 1985, 625–631 (1985).

Fong, S.-T. Thermal tolerance of adult Asiatic painted frog Kaloula pulchra from different populations. (National University of Tainan 2014).

Fontenot, C. L. & Lutterschmidt, W. I. Thermal selection and temperature preference of the aquatic salamander, Amphiuma tridactylum. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 6, 395–399 (2011).

Freidenburg, L. K. & Skelly, D. K. Microgeographical variation in thermal preference by an amphibian. Ecol. Lett. 7, 369–373 (2004).

Frishkoff, L. O., Hadly, E. A. & Daily, G. C. Thermal niche predicts tolerance to habitat conversion in tropical amphibians and reptiles. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 3901–3916 (2015).

Frost, J. S. & Martin, E. W. A Comparison of Distribution and High Temperature Tolerance in Bufo americanus and Bufo woodhousii fowleri. Copeia 1971, 750 (1971).

Galindo, C. A., Cruz, E. X. & Bernal, M. H. Evaluation of the combined temperature and relative humidity preferences of the Colombian terrestrial salamander Bolitoglossa ramosi (Amphibia: Plethodontidae). Can. J. Zool. 96, 1230–1235 (2018).

Gatten, R. E. & Hill, C. J. Social influence on thermal selection by Hyla crucifer. J. Herpetol. 18, 87–88 (1984).

Gatz, A. J. Critical Thermal Maxima of Ambystoma maculatum (Shaw) and Ambystoma jeffersonianum (Green) in Relation to Time of Breeding. Herpetologica 27, 157–160 (1971).

Gatz, A. J. Intraspecific Variations in Critical Thermal Maxima of Ambystoma maculatum. Herpetologica 29, 264–268 (1973).

Geise, W. & Linsenmair, K. E. Adaptations of the reed frog Hyperolius viridiflavus (Amphibia, Anura, Hyperoliidae) to its arid environment - IV. Ecological significance of water economy with comments on thermoregulation and energy allocation. Oecologia 77, 327–338 (1988).

Gélinas, N. Rôle du comportement thermorégulateur chez la grenouille du nord (Rana septentrionalis, Baird) adulte et le ouaouaron (Rana catesbeiana, Shaw) juvénile en rapport avec le besoin alimentaire. (Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières 1996).

Goldstein, J. A., Hoff, K. V. S. & Hillyard, S. D. The effect of temperature on development and behaviour of relict leopard frog tadpoles. Conserv. Physiol. 5, cow075 (2017).

González-del-Pliego, P. et al. Thermal tolerance and the importance of microhabitats for Andean frogs in the context of land use and climate change. J. Anim. Ecol. 89, 2451–2460 (2020).

Gouveia, S. F. et al. Climatic niche at physiological and macroecological scales: The thermal tolerance-geographical range interface and niche dimensionality. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 23, 446–456 (2014).

Gray, R. Lack of physiological differentiation in three color morphs of the cricket frog (Acris crepitans) in Illinois. Trans. Ill. State Acad. Sci. 70, 73–79 (1977).

Greenspan, S. E. et al. Infection increases vulnerability to climate change via effects on host thermal tolerance. Sci. Rep. 7 (2017).

Guevara-Molina, E. C., Gomes, F. R. & Camacho, A. Effects of dehydration on thermoregulatory behavior and thermal tolerance limits of Rana catesbeiana (Shaw, 1802). J. Therm. Biol. 93 (2020).

Gutiérrez Pesquera, L. Una valoración macrofisiológica de la vulnerabilidad al calentamiento global. Análisis de los límites de tolerancia térmica en comunidades de anfibios en gradientes latitudinales y altitudinales. (Pontificia Universidad Católica Del Ecuador 2015).

Gutiérrez Pesquera, M. Thermal tolerance across latitudinal and altitudinal gradients in tadpoles. (Universidad de Sevilla 2016).

Gutiérrez-Pesquera, L. M. et al. Testing the climate variability hypothesis in thermal tolerance limits of tropical and temperate tadpoles. J. Biogeogr. 43, 1166–1178 (2016).

Gvoždík, L., Puky, M. & Šugerková, M. Acclimation is beneficial at extreme test temperatures in the Danube crested newt, Triturus dobrogicus (Caudata, Salamandridae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 90, 627–636 (2007).

Gvoždík, L. Does reproduction influence temperature preferences in newts? Can. J. Zool. 83, 1038–1044 (2005).

Gvoždík, L. Mismatch Between Ectotherm Thermal Preferenda and Optima for Swimming: A Test of the Evolutionary Pace Hypothesis. Evol. Biol. 42, 137–145 (2015).

Gvoždík, L. & Kristín, P. Economic thermoregulatory response explains mismatch between thermal physiology and behaviour in newts. J. Exp. Biol. 220, 1106–1111 (2017).

Gvoždı́k, L. Postprandial thermophily in the Danube crested newt, Triturus dobrogicus. J. Therm. Biol. 28, 545–550 (2003).

Hadamová, M. & Gvoždík, L. Seasonal acclimation of preferred body temperatures improves the opportunity for thermoregulation in newts. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 84, 166–174 (2011).

Haggerty, J. Thermal tolerance of the common coqui frog (Eleutherodactylus coqui) in East Hawaii along an elevation gradient. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (University of Hawai’i at Hilo 2016).

Hanna, A. The effects of temperature on physiology in frogs and their dispersal of the temperate zone from the tropics. (Truman State University 2019).

He, J. et al. Influence of High Temperatures and Heat Wave on Thermal Biology, Locomotor Performance, and Antioxidant System of High-Altitude Frog Nanorana pleskei Endemic to Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9 (2021).

Heath, A. G. Behavioral Thermoregulation in High Altitude Tiger Salamanders, Ambystoma tigrinum. Herpetologica 31, 84–93 (1975).

Heatwole, H., De Austin, S. B. & Herrero, R. Heat tolerances of tadpoles of two species of tropical anurans. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 27, 807–815 (1968).

Heatwole, H., Mercado, N. & Ortiz, E. Comparison of Critical Thermal Maxima of Two Species of Puerto Rican Frogs of the Genus Eleutherodactylus. Physiol. Zool. 38, 1–8 (1965).

Holzman, N. & McManus, J. J. Effects of acclimation on metabolic rate and thermal tolerance in the carpenter frog, Rana vergatipes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 45, 833–842 (1973).

Hoppe, D. M. Thermal Tolerance in Tadpoles of the Chorus Frog Pseudacris triseriata. Herpetologica 34, 318–321 (1978).

Hou, P.-C. Thermal tolerance and preference in the adult amphibians from different altitudinal LTER sites. (National Cheng Kung University 2003).

Howard, J. H., Wallace, R. L. & Stauffer, J. R. Jr Critical thermal maxima in populations of Ambystoma macrodactylum from different elevations. J. Herpetol. 17, 400–402 (1983).

Hutchison, V. H. & Ritchart, J. P. Annual cycle of thermal tolerance in the salamander, Necturus maculosus. J. Herpetol. 23, 73–76 (1989).

Hutchison, V. H. & Murphy, K. Behavioral thermoregulation in the salamander Necturus maculosus after heat shock. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 82, 391–394 (1985).

Hutchison, V. H. The Distribution and Ecology of the Cave Salamander, Eurycea lucifuga. Ecol. Monogr. 28, 2–20 (1958).

Hutchison, V. H. Critical Thermal Maxima in Salamanders. Physiol. Zool. 34, 92–125 (1961).

Hutchison, V. H., Engbretson, G. & Turney, D. Thermal Acclimation and Tolerance in the Hellbender, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis. Copeia 1973, 805–807 (1973).

Hutchison, V. H. & Rowlan, S. D. Thermal Acclimation and Tolerance in the Mudpuppy, Necturus maculosus. J. Herpetol. 9, 367–368 (1975).

Hutchison, V. H. & Spriestersbach, K. K. Diel and Seasonal Cycles of Activity and Behavioral Thermoregulation in the Salamander Necturus maculosus. Copeia 1986, 612–618 (1986).

Jara Méndez, D., Krumel Castillo, M. & San Martín Venegas, E. Estudio de las preferencias térmicas y niveles de profundidad en tres estadios larvales de la especie Pleurodema thaul (Lesson, 1826) del Parque Nacional Laguna del Laja. (Universidad de Concepción 2020).

Jiang, S., Yu, P. & Hu, Q. A study on the critical thermal maxima of five species of salamanders of China. Acta Herpetol. Sin. 6, 56–62 (1987).

John-Alder, H. B., Morin, P. J. & Lawler, S. Thermal Physiology, Phenology, and Distribution of Tree Frogs. Am. Nat. 132, 506–520 (1988).

Johnson, C. R. Daily variation in the thermal tolerance of Litoria caerulea (Anura: Hylidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 40, 1109–1111 (1971).

Johnson, C. R. Thermal relations and water balance in the day frog, Taudactylus diurnus, from an Australian rain forest. Aust. J. Zool. 19, 35–39 (1971).

Johnson, C. R. Diel variation in the thermal tolerance of Litoria gracilenta (Anura: Hylidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 41, 727–730 (1972).

Johnson, C. R. & Prine, J. E. The effects of sublethal concentrations of organophosphorus insecticides and an insect growth regulator on temperature tolerance in hydrated and dehydrated juvenile western toads, Bufo boreas. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 53, 147–149 (1976).

Johnson, C. R. Observations on body temperatures, critical thermal maxima and tolerance to water loss in the Australian hylid, Hyla caerulea (White). Proc. R. Soc. Queensland 82, 47–50 (1970).

Johnson, C. R. Thermal Relations and Daily Variation in the Thermal Tolerance in Bufo marinus. J. Herpetol. 6, 35 (1972).

Johnson, C. Thermal relations in some southern and eastern Australian anurans. Proc. R. Soc. Queensland 82, 87–94 (1971).

Johnson, C. The effects of five organophosphorus insecticides on thermal stress in tadpoles of the Pacific tree frog, Hyla regilla. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 69, 143–147 (1980).

Katzenberger, M., Duarte, H., Relyea, R., Beltrán, J. F. & Tejedo, M. Variation in upper thermal tolerance among 19 species from temperate wetlands. J. Therm. Biol. 96 (2021).

Katzenberger, M. et al. Swimming with predators and pesticides: How environmental stressors affect the thermal physiology of tadpoles. PLoS ONE 9 (2014).

Katzenberger, M., Hammond, J., Tejedo, M. & Relyea, R. Source of environmental data and warming tolerance estimation in six species of North American larval anurans. J. Therm. Biol. 76, 171–178 (2018).

Katzenberger, M. Thermal tolerance and sensitivity of amphibian larvae from Palearctic and Neotropical communities. (Universidade de Lisboa 2013).

Katzenberger, M. Impact of global warming in Holarctic and Neotropical communities of amphibians. (Universidad de Sevilla 2014).

Keen, W. H. & Schroeder, E. E. Temperature Selection and Tolerance in Three Species of Ambystoma Larvae. Copeia 1975, 523–530 (1975).

Kern, P., Cramp, R. L. & Franklin, C. E. Temperature and UV-B-insensitive performance in tadpoles of the ornate burrowing frog: An ephemeral pond specialist. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 1246–1252 (2014).

Kern, P., Cramp, R. L., Seebacher, F., Ghanizadeh Kazerouni, E. & Franklin, C. E. Plasticity of protective mechanisms only partially explains interactive effects of temperature and UVR on upper thermal limits. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 190, 75–82 (2015).

Kern, P., Cramp, R. L. & Franklin, C. E. Physiological responses of ectotherms to daily temperature variation. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 3068–3076 (2015).

Kirsch, D. R., Fix, S., Davenport, J. M., Cecala, K. K. & Ennen, J. R. Body Size Is Related to Temperature Preference in Hyla chrysoscelis Tadpoles. J. Herpetol. 55, 21–25 (2021).

Köhler, A. et al. Staying warm or moist? Operative temperature and thermal preferences of common frogs (Rana temporaria), and effects on locomotion. Herpetol. J. 21, 17–26 (2011).

Kolbe, J. J., Kearney, M. & Shine, R. Modeling the consequences of thermal trait variation for the cane toad invasion of Australia. Ecol. Appl. 20, 2273–2285 (2010).

Komaki, S., Igawa, T., Lin, S.-M. & Sumida, M. Salinity and thermal tolerance of Japanese stream tree frog (Buergeria japonica) tadpoles from island populations. Herpetol. J. 26, 207–211 (2016).

Komaki, S., Lau, Q. & Igawa, T. Living in a Japanese onsen: Field observations and physiological measurements of hot spring amphibian tadpoles, Buergeria japonica. Amphibia-Reptilia 37, 311–314 (2016).

Krakauer, T. Tolerance limits of the toad, Bufo marinus, in South Florida. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 33, 15–26 (1970).

Kurabayashi, A. et al. Improved transport of the model amphibian, Xenopus tropicalis, and its viable temperature for transport. Curr. Herpetol. 33, 75–87 (2014).

Lange, L. Influences environnementales précoces et plasticité phénotypique: étude d’un modèle amphibien avec soins parentaux prénataux, l’Alyte accoucheur. (Université de La Rochelle 2020).

Lange, Z. Thermal quality explains shift in habitat association from forest to clearings for terrestrial-breeding frogs along an elevation gradient in Colombia. (John Carroll University 2019).

Lau, E. T. C., Leung, K. M. Y. & Karraker, N. E. Native amphibian larvae exhibit higher upper thermal limits but lower performance than their introduced predator Gambusia affinis. J. Therm. Biol. 81, 154–161 (2019).

Layne, J. R. Freeze tolerance and cryoprotectant mobilization in the gray treefrog (Hyla versicolor). J. Exp. Zool. 283, 221–225 (1999).

Layne, J. R. & Claussen, D. L. Seasonal variation in the thermal acclimation of critical thermal maxima (CTMax) and minima (CTMin) in the salamander Eurycea bislineata. J. Therm. Biol. 7, 29–33 (1982).

Layne, J. R. & Claussen, D. L. The time courses of CTMax and CTMin acclimation in the salamander Desmognathus fuscus. J. Therm. Biol. 7, 139–141 (1982).

Layne, J. R. & Claussen, D. L. Time courses of thermal acclimation for critical thermal minima in the salamanders Desmognathus quadramaculatus, D. monticola, D. ochrophaeus, and Plethodon jordani. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 87, 895–898 (1987).

Layne, J. R. Seasonal variation in the cryobiology of Rana sylvatica from Pennsylvania. J. Therm. Biol. 20, 349–353 (1995).

Layne, J. R. & Romano, M. A. Critical Thermal Minima of Hyla chrysoscelis, H. cinerea, H. gratiosa and Natural Hybrids (H. cinerea × H. gratiosa). Herpetologica 41, 216–221 (1985).

Lee, P.-T. Acidic effect on tadpoles living in container habitats. (Tunghai University 2019).

Leger, J. P. & Mathieson, W. B. Effects of Bombesin on Behavioral Thermoregulation in the Bullfrog. Brain Behav. Evol. 50, 304–312 (2008).

Li, Z. et al. Landscape Connectivity Limits the Predicted Impact of Fungal Pathogen Invasion. J. Fungi 6, 205 (2020).

Lillywhite, H. B. Temperature selection by the bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 40, 213–227 (1971).

Litmer, A. R. & Murray, C. M. Critical Thermal Capacities of Hyla chrysoscelis in Relation to Season. J. Herpetol. 54, 413–417 (2020).

Llewellyn, D., Brown, G. P., Thompson, M. B. & Shine, R. Behavioral Responses to Immune-System Activation in an Anuran (the Cane Toad, Bufo marinus): Field and Laboratory Studies. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 84, 77–86 (2011).

Longhini, L. S., De Almeida Prado, C. P., Bícego, K. C., Zena, L. A. & Gargaglioni, L. H. Measuring cardiorespiratory variables on small tadpoles using a non-invasive methodology. Rev. Cubana Invest. Biomed. 38 (2019).

López Rosero, A. C. Ontogenetic variation of thermal tolerance in two anuran species of Ecuador: Gastrotheca pseustes (Hemiphractidae) and Smilisca phaeota (Hylidae) and their relative vulnerability to environmental temperature change. (Pontificia Universidad Católica Del Ecuador, 2015).

Lotshaw, D. P. Temperature adaptation and effects of thermal acclimation in Rana sylvatica and Rana catesbeiana. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 56, 287–294 (1977).