Abstract

Plastic film mulching has been widely adopted to enhance crop yields in arid and semi-arid regions, but it has also resulted in severe environmental pollution and altered water and heat cycles in farmland ecosystems. However, the scarcity of training samples hinders large-scale mapping of plastic-mulched farmland (PMF) distributions. Here we generated the first 10-m PMF maps for the Chinese Loess Plateau spanning the period 2019–2021 (PMF-LP) by coupling the automatic training sample generation and classifier transfer methods. The resultant maps were validated using independent samples and showed satisfactory accuracies with F1-scores ranging from 0.80 to 0.86. The estimated PMF areas derived from the PMF-LP demonstrated good agreement with agricultural census data at the municipal level (R² ≥ 0.87). This is the first attempt to map PMF distributions at 10-m resolution on the Loess Plateau. The datasets generated in this study will be valuable for pollution assessments, yield forecasting, and greenhouse gas estimations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Plastic film mulching has been widely applied in China since 1978, due to its ability to improve grain crop yields and water use efficiency1,2,3. Over the past two decades, China has consistently held the global top position in plastic film coverage, with a covered area of 11.0 million ha4,5,6. However, the extensive application of plastic films has also caused severe environmental issues. Plastic films, mainly composed of polyvinyl chloride, have residues that are highly difficult to degrade in the soil, leading to severe “white pollution”1,7,8. Furthermore, plastic film mulching might have impacts on regional climates by altering the material and energy exchange between the land surface and the atmosphere3,9. Therefore, precise information about the spatial distributions of plastic-mulched farmland (PMF) over large areas is essential for planning agriculture production, mitigating plastic residue pollution, and understanding water and energy cycles in the agroecosystems7,10.

Plastic film mulching data is usually derived from labor-intensive field surveys. However, statistical data often lack accurate information about the locations and distributions of PMF. Benefiting from advances in Earth observation techniques, the quantity and accessibility of remote sensing images have increased, enabling effective large-scale monitoring of agriculture in a cost-effective and timely manner11,12,13. Furthermore, the emergence of cloud-based geospatial processing platforms, particularly the Google Earth Engine (GEE)14, has significantly enhanced the processing capabilities of remote sensing data15,16. These advancements have supported the establishment of region- and nation-wide land cover maps. However, up-to-date, PMF has received comparatively less attention than crops, and regional or national PMF maps are rarely publicly available, particularly in China.

Optical satellite-based PMF mapping has primarily advanced along two methodological pathways, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The first pathway refers to an index-based approach, which uses the unique spectral characteristics of PMF during the crop sowing period to construct dedicated spectral indices, followed by setting optimal thresholds to identify PMF9,17,18,19,20. During the sowing period, newly applied plastic films exhibit a bright-white reflectance—a feature that enables the differentiation of PMF from other land cover types. Based on this feature, previous studies have developed specialized spectral indices (e.g., PMLI9, mPMCI19) for PMF identification. This method offers high efficiency in regions with high-quality imagery, as it enables rapid recognition of PMF using sowing-period spectral signals. Its core limitation, however, arises from the short time window available for PMF recognition. This window lasts approximately one month and mainly spans April to May in northern China18,21. Cloud contamination during this critical period may disrupt image acquisition, leaving gaps in large-area PMF maps and making it difficult to generate seamless PMF distribution product.

The second pathway employs machine learning classifiers, such as Random Forest and Support Vector Machine22,23,24,25, which address the gaps inherent to index-based approach by reducing reliance on sowing-period imagery. Owing to the predictive abilities of machine learning, even if a PMF pixel is cloud-contaminated during the crop sowing period, machine learning classifiers can still effectively identify it with the clear-sky images from other growth stages26,27. This capability has facilitated seamless land cover mapping at regional and national scales. Yet machine learning faces its own critical challenge: large-scale PMF mapping requires abundant, representative training samples, and such samples remain scarce in most regions28,29,30,31,32.

Index-based method enables efficient PMF recognition but cannot generate seamless maps, while machine learning produces seamless PMF distributions yet faces sample scarcity. This kind of complementary strengths and limitations highlight the potential of integrating the two approaches. Index-based methods can automatically generate initial training samples in areas with high-quality sowing-period imagery, which addresses the sample scarcity constraining machine learning33,34. Conversely, machine learning can fill the gaps caused by cloud contamination27; it leverages multi-temporal features to produce seamless PMF distributions. This integration, however, requires the design of robust PMF indices to ensure sample quality, particularly in regions with complex, fragmented landscapes. These regions differ from Xinjiang, where most existing PMF indices were developed specifically for large, uniform land parcels9,18,19,20. A key unresolved challenge lies in the lack of adaptability of these existing indices to complex and fragmented regions.

Moreover, classifier transfer, which involves applying classifiers trained in a source domain to accomplish related tasks in a target domain, is also employed to address the scarcity of training samples35,36. This approach supports more rapid land cover mapping across large scales and multiple years compared to locally adaptive classifiers. However, existing studies predominantly focused on transferring supervised classifiers for crop classification37,38,39,40,41. It remains unclear whether this approach is applicable for the rapid mapping of PMF at large scales. Furthermore, the factors influencing the accuracy of PMF identification using this method are also unknown.

To address the aforementioned issues, we developed a novel mapping framework to create PMF distribution maps at 10 m spatial resolution for the Loess Plateau (PMF-LP) spanning 2019–2021. Our process comprises four components: (1) automatic generation of training samples based on newly proposed PMF indices and optimal thresholds; (2) assessment of the spatiotemporal transferability of pre-trained classifiers for PMF mapping; (3) mapping of seamless PMF distribution maps; (4) validation of PMF-LP accuracy using independent samples and agricultural census data.

Methods

Study area

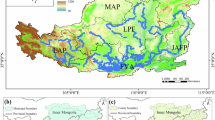

The Loess Plateau (33°43′ N–41°16′ N, 100°54′ E–114°33′ E) covers an area of approximately 6.4 × 105 km2 (Fig. 1a). This region experiences a warm temperate continental monsoon climate42, characterized by hot-rainy summers and cold-dry winters (Fig. 1c). The mean annual precipitation varies spatially across the region, ranging from 200 mm in the northwest to 800 mm in the southeast, while annual evapotranspiration ranges from 1,400 to 2,000 mm43,44,45. Transparent plastic film predominates in this region (Fig. 1d–g), covering about 90% of the total plastic-mulched fields9,46,47. Thus, this study focused solely on farmland mulched with transparent plastic film. To balance the computational cost and the need for adequate training samples, the study area was divided into 32 mapping units based on the municipal administrative boundaries (Fig. S1).

Overview of the study area. (a) Location of the Loess Plateau. Rectangular regions (A~K) are representative mulched regions where high-resolution Google Earth images are available for visual interpretation. (b) Topography information88. (c) Köppen-Geiger climate classification. BSk: arid, steppe, cold; BWk: arid, desert, cold; Cwa: temperate, dry winter, hot summer; Dwa: cold, dry winter, hot summer; Dwb: cold, dry winter, warm summer; Dwc: cold, dry winter, cold summer; and ET: polar, tundra. (d–g) Zoom-in views of Google Earth images of plastic-mulched farmlands during the mulching stage in 2020 for the rectangular regions of A, E, I, and K, respectively.

Three major crops—maize, potato, and winter wheat—are extensively cultivated on the Loess Plateau. Maize and potato, the primary plastic-mulched crops, are typically sown in mid-April and harvested in late September, with plastic film applied shortly before and after sowing. Winter wheat is sown in October of the prior year and harvested in late June. Only a very small portion of winter wheat is mulched with plastic film in the study area. The crop calendars for these main crops are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Sentinel-2 data

In this study, all available Sentinel-2 surface reflectance (SR) data covering the Loess Plateau from 2019 to 2021, archived in GEE, were employed as input data since SR data are unavailable for this region before 2019. Considering the growth patterns of plastic-mulched crops (Fig. 2), Sentinel-2 data were further limited to March to October, and quality assessment (QA) bands were used to mask clouds and cirrus pixels. We counted the number of yearly cloud-free images per pixel from 2019 to 2021, and found that the mean numbers were 46 in 2019, 45 in 2020, and 43 in 2021, respectively (Fig. S2).

Cropland data

To simplify the process of PMF mapping and reduce commission errors caused by other land cover types48,49,50, three cropland layers, including the GLC_FCS30D51, CACD52, and CLCD53, were overlaid and utilized to exclude non-cropland pixels. All cropland datasets were resampled to 10-m resolution using the nearest-neighbor method.

Google Earth high-resolution images (GE-HRIs)

The GE-HRIs were utilized to assist in obtaining validation samples. Additionally, two representative rectangular regions (20 km × 20 km) with at least one GE-HRI image available during the mulching stage were selected in each province (yellow areas A~K in Fig. 1a). The samples interpreted in these rectangular regions (300 PMF/Non-PMF points for each region) were employed to determine optimal thresholds for the newly proposed PMF indices.

Agricultural statistics

The PMF census data from 2019 to 2021, sourced from municipal-level agricultural statistical offices, were collected to assess the mapped PMF areas. It is noteworthy that plastic film usage in the statistical yearbooks of most cities on the Loess Plateau is quantified in tons. Consequently, in this study, we only obtained statistical data for 12 cities (Fig. S3), where plastic film usage was measured in terms of area. Since these 12 cities account for nearly one-third of the total area of the Loess Plateau, the accuracy assessment of the mapped PMF areas based on the municipal statistical data was considered representative and reliable.

Framework for PMF mapping

The mapping framework of this study is summarized in Fig. 3. First, cloud-free Sentinel-2 time series data were used to fit harmonic curves, generating feature variables that served as input variables for the classifiers. Next, a temporal signature analysis of various cropland-related land covers was conducted. Distinctive signatures during the mulching period guided the design of PMF indices, which effectively separated PMF from other land cover types. These indices were then employed to identify PMF in cloud-free areas and automatically generate training samples. Third, random forest classifiers were developed to recognize PMF based on the feature variables and the automatically generated training samples. The transferability of these classifiers was then evaluated in terms of temporal and spatial–temporal transferability. Finally, the PMF mapping results were assessed against ground reference samples and statistical PMF area data.

Framework for mapping PMF distributions on the Chinese Loess Plateau. PMF: Plastic-mulched Farmland, Non-PMF: Non-plastic-mulched Farmland. The MBPMFI (Max Blue Band-based Plastic-mulched Farmland Index) and BPMFI (Blue Band-based Plastic-mulched Farmland Index) are the two novel PMF indices proposed in this study. The entire growing season of plastic-mulched crops was divided into four stages: pre-mulching stage (PMS), mulching stage (MS), growing stage (GS), and flourishing stage (FS), as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Automatic generation of training samples

Optical characteristics of PMF

The multi-temporal Sentinel-2 images from a representative sub-region in Pingliang City, Gansu Province, are shown in Fig. 4c–j to analyze the optical characteristics of PMF. The PMF, plastic greenhouses (PGs), and vegetation (mainly winter crops) within this sub-region represented the primary agricultural-related land cover types on the cultivated farmland on the Loess Plateau. During the crop sowing period, PMF exhibited a bright-white color due to the plastic films, making it easily distinguishable from vegetation (dark-green color) but potentially confusing it with PGs (blue-gray or white color) (Fig. 4c–f). Subsequently, from June to September (Fig. 4g–i), the crop canopy covered the PMF, giving it a green appearance similar to vegetation. Meanwhile, since crops grew inside the PGs, the PGs maintained blue-gray or white appearance consistently. Thus, this period was ideal for differentiating between PGs and PMF.

Time-series profiles of plastic-mulched farmland (PMF), plastic greenhouses (PGs), and vegetation in a representative sub-region of Pingliang City, Gansu Province, China. (a) High-resolution Google Earth imagery during the crop sowing period. The red, black, and green outlined plots denote the PMF, PGs, and vegetation, respectively. (b) Time series of PMF, PGs, and vegetation in the Sentinel-2 blue band. The red, gray, and blue buffers indicate one standard deviation. The brown, gray, yellowish-green, and green rectangular areas denote the pre-mulching stage (PMS), mulching stage (MS), growing stage (GS), and flourishing stage (FS), respectively. (c)~(j) Sentinel-2 images with a true-color composite of blue, green, and red bands on different dates across the entire crop growing season.

Theoretically, the conspicuous bright white characteristic during the crop sowing period indicates the substantial reflectance of PMF in the visible spectrum. Temporal profiles of the Sentinel-2 blue band revealed distinguishable patterns among PMF, PGs, and vegetation (Fig. 4b). Specifically, during the crop sowing period, areas covered by plastic films had higher reflectance in the blue band compared to those covered by the crop canopy. Subsequently, as crops grew on the PMF, the increased absorption in the visible spectrum led to a gradual decrease in PMF reflectance in the blue band. Particularly, during the peak growing stage of crops, PMF reached its lowest reflectance in the blue band.

In addition to the blue band, PMF demonstrated clear differentiation from other land cover types in the green and red bands, as well as in the red-edge band (red edge1) (Fig. S4). Notably, this study focused exclusively on the blue band due to the consistent temporal profiles observed across these four bands. Furthermore, the consistency of PMF’s blue-band characteristics was tested across different regions on the Loess Plateau (Fig. S5). The results showed that PMF exhibited similar temporal profiles across these regions, consistent with the pattern illustrated in Fig. 4b (i.e., a clear peak in the mulching stage and a trough in the flourishing stage). However, in parts of Inner Mongolia and Shanxi, PMF and Non-PMF pixels showed relatively higher spectral similarity (Fig. S5d,f).

Developing PMF indices to automatically generate training samples

Following the temporal profile analyses, the entire growing season of plastic-mulched crops was divided into four distinct stages (Fig. 5). The pre-mulching stage (PMS) (March to early April) involves primarily field plowing, with seldom plastic film coverage on the farmland. The mulching stage (MS) (mid-April to May) represents the gradual coverage of farmland with plastic films. During the growing stage (GS) (June to July), crops begin to grow but do not yet fully cover the cropland. The flourishing stage (FS) (August to September) is characterized by vigorous crop growth, with the crop canopy fully sheltering the cropland.

Schematic diagrams illustrating the construction of plastic-mulched farmland indices. (a) Time-series profiles of the plastic-mulched farmland (PMF) and non-plastic-mulched farmland (Non-PMF) in the Sentinel-2 blue band. (b) Defined stages used to divide the entire growing season of plastic-mulched crops into four parts. (c) Explanation of the variables used to represent the unique characteristics of PMF.

Across these stages, the distinctive spectral responses of PMF in the blue band were summarized as follows: a relatively large range of reflectance dynamics from PMS to MS (Δbluemax-PMS) due to the gradual deployment of plastic film, and the maximal range of reflectance dynamics from GS to FS (Δbluemax-FS) due to the abundant visible spectrum absorption for photosynthesis. Considering that both Δbluemax-PMS and Δbluemax-FS for PMF were relatively higher than those for other land cover types, multiplying these two metrics could effectively highlight PMF while suppressing other land cover types. Specifically, two local troughs (bluePMS and blueFS) were the minimum reflectance values of the blue band during the PMS and FS, respectively. The local peak (bluemax) refers to the maximum reflectance value of the blue band during the MS. Additionally, the metric bluemax was also employed to enhance PMF signals, as it exhibited the highest reflectance value throughout the period from PMS to FS. Finally, two PMF indices, the Max Blue Band-based Plastic-mulched Farmland Index (MBPMFI) (Eq. 1) and the Blue Band-based Plastic-mulched Farmland Index (BPMFI) (Eq. 2) were defined.

where the multiplier 100 was used to linearly stretch the BPMFI to a wider range.

Notably, since the primary objective of this study was to recognize PMF and given the relative scarcity of PGs compared with PMF54,55, land cover types were categorized into two classes: PMF and Non-PMF. Table S1 presents the statistical analysis results of the MBPMFI and BPMFI indices for both PMF and Non-PMF samples collected from the rectangular regions in Fig. 1a. Generally, the p-values for the two PMF indices across different provinces were equal to 0, indicating the great potential of MBPMFI and BPMFI to enhance PMF signals while suppressing Non-PMF signals. Referring to previous studies56,57, sample points from the rectangular regions were exploited to establish province-specific thresholds for each PMF index. The optimal thresholds for the two novel indices were separately determined based on accuracy changes under different thresholds (Fig. 6). Particularly, for Henan Province, we adopted the same thresholds as those used in Shanxi Province. Finally, PMF and Non-PMF pixels in cloud-free areas were automatically extracted. To improve the reliability of the training samples, only cropland classified as PMF or Non-PMF by both PMF indices was included in the final candidate training sample pools (Fig. S6d,h).

The idea of incorporating two different PMF candidate layers to generate samples is driven by the assumption that relying on a single layer may introduce uncertainties, whereas combining multiple layers can generate pixels with a higher confidence level58. Thus, our dual-index screening process ensured that only high-confidence pixels were included in the training pool (Fig. S6f–h). This refinement significantly improved the quality of training data for subsequent machine learning classification.

Training sample generation and refinement

Based on the candidate sample pools, a stratified random sampling approach was adopted to select 2000 pixels for PMF and Non-PMF within every mapping unit for the year 2020. To further ensure the reliability of these samples and eliminate potential errors, a strict spatial filter (8-neighbor filter) was conducted for these samples59,60,61. Only pixels sharing the same class type as the surrounding eight pixels were considered as high-quality samples. These samples were subsequently utilized as training data for classifiers to identify PMF.

Feature calculation and selection

The visible bands (Blue, Green, and Red) and shortwave-infrared bands (SWIR1 and SWIR2) from Sentinel-2 were selected as input features for classifiers, due to their high potential to separate PMF from other land cover types18,20,62. Since plastic films can influence energy balance and water cycles on the land surface9,22, several vegetation indices were also included as input features (Table S2): NDVI63, GCVI64, LSW65, NMDI66, BSI67, DBSI68, PMLI9. Moreover, the newly proposed PMF indices, MBPMFI and BPMFI, were also incorporated.

Compared with Non-PMF, PMF exhibited unique temporal profiles resembling sine waves in the blue band (Fig. 5a). To characterize these profiles and fill missing values caused by cloud contaminations, harmonic regression69,70 (Eq. 3) was conducted to fit time series curves for PMF across the five surface reflectance bands and seven vegetation indices. The time window for fitting the time-series curves extended from March 1st to October 31st, covering the entire growing season of plastic-mulched crops. Each band was treated as a time-dependent function, denoted as f(t).

where the independent variable t is the day of year expressed as a fraction between 0 (January 1st) and 1 (December 31st) for a satellite image, c is the intercept term, n is the order of harmonic series, ak are the cosine coefficients, bk are the sine coefficients, and ω is the angular frequency.

In the above harmonic regression formula, parameters n and ω need to be adjusted to balance the fitting closeness to the observation points and prevent overfitting. Based on the ground reference PMF samples within the rectangular regions (yellow areas A~K in Fig. 1a), we picked n = 2 and ω = 1.5 as the optimal parameters by evaluating the root mean square error (RMSE) of the fitting progress (Fig. S7). Therefore, we obtained the final harmonic regression formula (Eq. 4).

After the harmonic regression, the time series of each band was represented by five coefficients: c, a1, b1, a2, and b2. Furthermore, the peak value (peak) of each band and their corresponding dates (timing) were also extracted from the fitted harmonic regression curves. These coefficients combined with MBPMFI and BPMFI resulted in a total of 86 (12 × 7 + 2 = 86) features.

To select the important features and discard unimportant ones which may adversely affect the accuracy and computational cost of supervised classifiers71,72, a combination of time-series correlation analysis and random forest feature importance analysis was employed to reduce the number of features (Fig. S8). The reduction process included: (1) grouping bands with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.90, retaining only the band with the highest feature importance (retained bands: Blue, SWIR2, BSI, DBSI, GCVI, NMDI, and PMLI); (2) further limiting the seven harmonic coefficients to the peak, a₁, and b₂ terms based on their importance evaluation results; (3) retaining MBPMFI and BPMFI due to their higher importance compared with other features (Fig. 7). Ultimately, a total of 23 features were adopted as input variables for the classifiers in this study (Table S3). A comparison of PMF mapping accuracies using 86 features versus 23 features revealed no significant difference (α = 0.05) (Fig. S9).

Feature importance of top 20 features calculated by the random forest classifiers trained in each city on the Loess Plateau. Since the feature importance in each city is not comparable, we normalized the individual value by dividing the total importance of all features in each city and scaled them by multiplying 1000. Suffixes “constant”, “cos”, “sin”, “cos2”, and “sin2” correspond to the harmonic coefficients “c”, “a1”, “b1”, “a2”, and “b2”, respectively.

Classifier transferability analysis

We employed the pixel-based random forest (RF) classifier73 available on the GEE platform to identify PMF spatial distributions within each mapping unit, based on the selected optimal features and automatically generated samples mentioned above. As an ensemble algorithm comprising numerous decision trees, RF has been widely used for large-scale land cover classification74,75, crop type mapping34,76, and classifier transferability analysis40,77, due to its capabilities in handling high-dimensional data, tolerating noise, and preventing overfitting78,79. Two key hyperparameters need to be set when using RF, which are the number of trees (Ntree) to be generated and the number of features (Mtry) used for testing the best split when growing the trees78. The former parameter was set as 100 since the out-of-bag errors in different mapping units ceased to decrease beyond 100 trees (Fig. S10); the latter one was set as the default value (i.e., the square root of the number of features).

Revealing the temporal and spatial–temporal transferability of classifiers can facilitate multi-year PMF mapping without the requirement of domain- and year-specific training samples. The classifiers trained within each mapping unit in 2020 (reference scenario, Scenario–Ref) were tested in two transferability scenarios to evaluate their temporal and spatial–temporal transferability: (1) classifiers were applied to recognize PMF within the same units for 2019 and 2021 to assess their temporal transferability (Scenario–T); and (2) classifiers were employed to recognize PMF in all other remaining units for 2019 and 2021 to test their spatial–temporal transferability (Scenario–ST). Note that classifiers trained on data from 2020 were not assessed in other spatial regions in the same year of 2020, because the primary goal of classifier transfer in this study is to rapidly retrace historical PMF distributions. In each scenario, the F1-score (F1) was calculated based on validation samples as accuracy evaluation metric. Furthermore, to assess changes of F1 in each transferability scenario against reference scenario, the percentage change in F1 values (F1change) was also computed (Eq. 5).

Accuracy assessment

We assessed the quality of the generated PMF maps with two measures. First, we performed a pixel-wise quantitative assessment for the PMF maps in 2019–2021, using more than 5000 ground reference samples each year (Table S4). Four accuracy metrics were adopted: producer accuracy (PA), user accuracy (UA), overall accuracy (OA), and F1-score (F1). Next, the coefficient of determination (R2) was used to quantitatively measure the consistency of the PMF areas derived from agricultural statistics and those from the resultant maps.

The validation samples were collected by visually interpreting GE-HRIs and Sentinel-2 images, based on the unique characteristics of PMF. A two-step strategy was designed to generate the validation samples: (1) croplands exhibiting a white hue during the mulching stage (MS) and a dark green hue during the flourishing stage (FS) in the true-color composite images were more likely to be PMF than those showing other hue changes; (2) the time-series curves of PMF in the blue band displayed more pronounced peak values during the mulching stage (MS) and trough values during the flourishing stage (FS) compared to other land cover types. Pixels meeting above two rules were finally labeled as PMF; otherwise, they were grouped into Non-PMF. Ultimately, we obtained 7,091, 12,140, and 6,714 validation samples for 2019, 2020, and 2021, respectively (Fig. S11).

Data Records

The plastic-mulched farmland distribution maps for the Loess Plateau of China (PMF-LP) generated in this paper are openly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1336942680. This dataset consists of a series of GeoTIFF images with the EPSG:4326 spatial reference system. In these images, the values 0 and 1 represent Non-PMF and PMF, respectively. PMF-LP features a 10-m spatial resolution and an annual temporal resolution, covering the years from 2019 to 2021. For example, in the file name “PMF-LP-2019.tif”, “2019” denotes the year to which the data belongs. The maps can be visualized and analyzed using ArcGIS, QGIS or other similar software. Users are encouraged to independently verify the PMF maps.

Technical Validation

Classifier transferability analysis

All locally adaptive classifiers in the reference scenario (Scenario–Ref) showed satisfactory accuracy in PMF mapping (Fig. 8a). In this scenario, the F1 values of PMF ranged from 0.64 to 0.94, with an average of 0.85. For all cities, the F1 values were close to or above 0.80, except in the NID (0.75), Baotou (0.75), Hohhot (0.64), and Ordos (0.73). The high F1 values indicated that the locally adaptive classifiers trained in this study can meet the practical demands for actual PMF mapping.

Transferability evaluation of the pre-trained classifiers for plastic-mulched farmland (PMF) mapping. (a) F1 values of PMF mapping based on locally adaptive classifiers trained on data in 2020 within each city of the Loess Plateau (Scenario–Ref). (b) Percentage change in F1 values (F1change) for temporal transferability scenario (Scenario–T). (c) F1change for spatial–temporal transferability scenario (Scenario–ST).

The F1 values from each transferability scenario (Scenario–T, Scenario–ST) were compared with those from the reference scenario (Scenario-Ref) in each city, and the percentage change in the F1 values (F1change) was also computed (Fig. 8b,c). Generally, the comparison results showed that for all cities, the F1 values decreased from the Scenario–Ref to Scenario–ST in an orderly manner (Scenario–Ref > Scenario–T > Scenario–ST). In Scenario–T (Fig. 8b), the average F1change was −2.92% for 2019 and −6.07% for 2021. Except in Qinghai, Datong, and Yangquan, where the F1change values were below −20% in 2021, the F1change values for all other cities were above −20%. In Scenario–ST (Fig. 8c), the average F1change was −13.86% for 2019 and −21.94% for 2021, which was absolutely 10.94% and 15.87% lower than in Scenario–T for 2019 and 2021, respectively. Furthermore, one-third of the cities on the Loess Plateau showed a percentage decline in the F1 values over −20% in Scenario–ST. The greater decrease in F1 values in Scenario–ST compared to Scenario–T indicated that Scenario–ST was hardly suitable for the mapping of PMF distributions across different years.

Pixel-wise accuracy assessment

Given the strong performance of the temporal classifier transfer (Scenario–T) for multi-year PMF mapping, classifiers trained on automatically generated samples and optimal features in 2020 were exploited to map PMF distributions (PMF-LP) for 2019–2021. The accuracy assessment for the three years was implemented based on the validation samples of the entire study area (Table 1). The OA of the resultant maps for all three years varied from 0.82 (2021) to 0.87 (2020). PMF was accurately identified, with F1 values ranging from 0.80 in 2021 to 0.86 in 2020, averaging 0.83 over the three years. For all three-year classification results, PMF exhibited higher PA than UA, indicating that commission errors in PMF recognition were higher than the omission errors. The higher commission errors indicated that some Non-PMF pixels were incorrectly classified as PMF, potentially leading to an overestimation of PMF areas. Detailed pixel-wise accuracy assessments for each city on the Loess Plateau are presented in Tables S5–S7.

Comparison with agricultural statistics

The PMF areas derived from our maps exhibited high consistency with the agricultural statistics, with coefficients of determination (R²) of 0.92, 0.93, and 0.87 for the year 2019, 2020, and 2021, respectively (Fig. 9). Notably, the resultant maps for 2021 (Fig. 9c) tended to overestimate PMF areas, particularly in Qinghai and northern Shanxi, likely due to snow and cloud residuals being misclassified as PMF. In conclusion, the strong consistency between the estimated areas and the statistical data underscored the reliability of the distribution maps produced in this study.

Spatial distributions of PMF on the Loess Plateau

The final PMF mapping results are shown in Fig. 10. To quantify the intensity of plastic film usage across different cities on the Loess Plateau, we calculated the ratio of plastic-mulched area (derived from the resultant maps) to the total cultivated land area (derived from cropland layers) for each city (Fig. 10c). PMF was widely distributed over the Loess Plateau, exhibiting a pattern of extensive dispersion and localized clustering (Fig. 10a). The Hetao Irrigation District exhibited the highest intensity of plastic film usage at 18%, followed by Northern Shanxi at 17%, and the Eastern Gansu-Southern Ningxia region at 16% (Fig. 10c). In these arid and cold regions, plastic films have been extensively used for decades to ensure crop yields by regulating temperature and conserving moisture3,5,81.

Spatial patterns of plastic-mulched farmland (PMF) on the Loess Plateau. (a) Frequency of plastic film mulching. Site A, B, C, and D are the zoom-in view cases in Fig. 11. (b) Area of PMF within each city in 2020. (c) Intensity of plastic film mulching in 2020. Intensity of plastic film mulching is defined as the ratio of PMF area to total cultivated area.

To further validate the PMF mapping results, a more detailed visual evaluation was conducted by selecting representative areas in different years (Fig. 11). Obviously, PMF was effectively distinguished from other land cover types, regardless of various cropland sizes and shapes. In site A, Bayan Nur, Inner Mongolia Province, PMF was densely distributed in regular rectangles (Fig. 11a). There were clear separations between PMF and roads in the mapping results. When the classifiers trained in 2020 were applied to 2019 and 2021, some PMF pixels in site A were not identified in 2019 (Fig. 11b), while in 2021, there were instances of erroneously classifying Non-PMF pixels as PMF (Fig. 11f). Site B in Xinzhou of Shanxi Province had large fields with irregular shapes compared to site A (Fig. 11g). The PMF mapping results from 2019 to 2021 at this site showed strong spatial agreement with the Sentinel-2 true-color composite images (Fig. 11h,j,l). In site C, Xianyang, Shaanxi Province, PMF was scattered among winter crops (Fig. 11m). The mapping results showed good separability between winter crops and PMF across different years (Fig. 11n,p,r). For site D in Linxia of Gansu Province, the cultivated farmland was primarily characterized by terraced fields, presenting elongated and irregular shapes (Fig. 11s). These terraced fields were interspersed with vegetations, buildings, and bare lands. The mapping results were also satisfactory in this site (Fig. 11t,v,x).

Spatial details of the plastic-mulched farmland (PMF) map subsets from different regions in the years of 2019, 2020, and 2021. Site A, B, C, and D correspond to the four typical regions marked in Fig. 10. The 1st, 3rd, and 5th columns are the Sentinel-2 (S2) images with a true-color composite of red, green, blue bands in the years of 2019, 2020, and 2021, respectively. The 2nd, 4th, and 6th columns are the PMF maps established in this study.

Comparisons with existing PMF maps

We compared our dataset with an existing product of China-PMF-10. China-PMF-10 is a 10-m resolution national PMF map for 2020, developed by Niu et al.82. A pixel-wise accuracy evaluation was conducted using 12,140 validation samples collected in this study. Results showed that the PA (0.57), F1 (0.71), and OA (0.79) of China-PMF-10 were 0.31, 0.15, and 0.08 lower than those of our dataset (Fig. 12b). Notably, the low PA of China-PMF-10 indicated severe omission errors, with many PMF pixels misclassified as Non-PMF. In contrast, China-PMF-10 had a higher UA (0.92) than our dataset (0.84), which suggested our dataset had more significant commission errors, specifically some Non-PMF pixels misclassified as PMF. Additionally, the PMF areas derived from the two datasets were compared with statistical data. Our dataset aligned better with local census records (R² = 0.93) than Niu et al.’s dataset (R² = 0.74), which confirmed it better reflected the true extent of PMF on the Loess Plateau (Fig. 12a).

Furthermore, the accuracy stability of the two datasets was tested with increasing elevation and slope. Compared with Niu et al.’s dataset, our PMF-LP maintained more stable classification accuracy. Specifically, the F1-score of Niu et al.’s dataset declined notably in areas where elevation >1600 m or slope >6° (Fig. 12c,d). Visual comparisons of representative regions further confirmed the superior performance of our PMF-LP in topographically challenging areas (Fig. S12). Overall, while Niu et al.’s dataset provides valuable national-scale context, our study offers a supplementary dataset that is more precise, time-continuous (2019–2021), and adapted to the Loess Plateau.

Usage Note

Feasibility of MBPMFI and BPMFI for automatic training sample generation

Training samples are critical for land cover classification, but their scarcity significantly hinders large-scale, multi-year landcover mapping28,29,30,31,32. This problem is worsened as PMF is a relatively understudied land cover type compared with crop types. To tackle this, we created two blue band-based indices (MBPMFI and BPMFI) for automatic training sample generation, providing a more convenient and labor-saving way compared with field surveys or visual interpretation. The needed prior information (like mulching dates) is easy to get from local experiences, and their only dependence on the blue band makes calculations simple.

Previous studies have shown that PMF indices based solely on optical images from the mulching stage often struggle to distinguish PMF from bare land and impervious surfaces9,18,20, which limits their applicability in complex environments. In this study, MBPMFI was also affected by residual impervious surface pixels that were not excluded by the cropland mask (Fig. S6f). By contrast, BPMFI was designed to capture PMF characteristics across the pre-mulching, mulching, and flourishing stages. For example, it used the difference between the blue-band peak in the mulching stage and the trough in the flourishing stage to further exclude impervious surface (Fig. S6g), since impervious surface lacks this temporal variation. This index exhibited greater robustness than MBPMFI in distinguishing PMF from backgrounds (Fig. S6g). However, the calculation of BPMFI requires images from three distinct periods, and such data may be unavailable in cloudy regions. Thus, MBPMFI is more practical for PMF recognition when only mulching-stage images are accessible.

Threshold stability of the MBPMFI and BPMFI

In this study, we employed ground truth samples from rectangular regions (Fig. 1a) to determine the threshold for each province on the Loess Plateau. To evaluate the stability of MBPMFI and BPMFI thresholds, we tested the mapping accuracy in the rectangular regions based on thresholds ±50% off the best threshold (Fig. 13). The F1 values ranged from 0 to 0.98 for MBPMFI and from 0.80 to 0.97 for BPMFI with the thresholds ±50% off from the best threshold across all regions. The stable F1 values of BPMFI indicated that it is not sensitive to threshold variations, which makes it well-suited for large-scale PMF mapping.

According to the results of our study, the best BPMFI threshold was 0.40 for Qinghai, Shaanxi, and Shanxi, and 0.80–1.10 for Gansu, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia. The relatively large difference in the best thresholds may be attributed to variations in plastic materials18,56 and crop species grown in the fields. The former affects the peak reflectance of PMF during the mulching stage, and the latter influences the absorption of the visible spectrum during the flourishing stage. The more detailed relationship between these factors and the spectral signatures of PMF deserves to be explored in the future. Additionally, based on the threshold stability assessment in Fig. 13, we recommend using a BPMFI threshold of 0.40–0.60 (i.e., approximately 50%–150% of the optimal threshold) and a MBPMFI threshold of 0.14–0.15 (i.e., approximately 90%–110% of the optimal threshold) for PMF recognition across the entire Loess Plateau. But for high-precision PMF mapping, it is suggested to segment the whole area into sub-regions and determine the optimal thresholds separately for each region.

Feasibility and error of classifier transfer for PMF mapping

Since training samples for PMF are limited, the feasibility of employing classifier transfer for PMF mapping has not been thoroughly explored. The findings of this study showed reduced performance in both transferability scenarios compared to the no-transfer case (Scenario–Ref). The temporal classifier transfer (Scenario–T) was more suitable for retracing historical PMF distributions than spatial–temporal classifier transfer (Scenario–ST), with percentage changes in F1 being less than 7.0% on average compared to the no-transfer case. Several potential factors that may cause performance reduction in Scenario–T and Scenario–ST could be categorized into three main groups: (1) missing clear Sentinel-2 data during the mulching stage; (2) snow and cloud residual contaminations during the pre-mulching stage; and (3) variations in mulching dates across different regions and years.

First, high-quality Sentinel-2 data during the mulching stage is crucial for enlarging the inter-class variations between PMF and Non-PMF. Particularly, the local peak value in the blue band (i.e., Blue_peak) is the most important signature for PMF mapping. Missing data during the mulching stage could result in the disappearance or distortion of the local peak values, causing classifiers trained on regions/years with high-quality data to fail in mapping PMF in regions/years with missing data. For example, during the mulching stage, more than half of the pixels in Qingyang had more than four clear-sky observations (Fig. 14a), while nearly 75% of the pixels in Henan had fewer than three clear-sky observations (Fig. 14b). Consequently, the local peaks of the harmonic regression curves in Henan (Fig. 14e) were lower than those in Qingyang (Fig. 14d) during 2019–2021, which led to low accuracy when using classifiers trained on Qingyang data from 2020 to recognize PMF in Henan for 2019 (F1 = 0.64) and 2021 (F1 = 0.49).

Explanations for the failures of Plastic-mulched farmland (PMF) mapping caused by data missing and cloud contamination. (a–c) Percentage of clear-sky observations at each cropland pixel during the mulching stage in Qingyang, Henan, and Qinghai. (d–f) Harmonic regression curves of PMF in Qingyang, Henan, and Qinghai for the year 2019, 2020, and 2021. The gray buffer represents mulching period. The black, green, and red buffers indicate one standard deviation. (g) A representative example in Qinghai for depicting the adverse effects of snow and clouds on PMF mapping.

Next, clouds and snow, which exhibit similar bright characteristics in all visible bands as PMF, are difficult to be thoroughly masked out using only the quality assessment (QA) bands of Sentinel-283. For example, although the percentage of clear-sky observations in Qinghai was the same as in Qingyang (Fig. 14a,c), snow and cloud residuals distorted the harmonic regression curves in Qinghai in 2021 (Fig. 14f,g), leading to the performance loss when using classifiers trained on Qinghai (or other city) data from 2020 to recognize PMF in the same region for 2021.

Finally, variations in crop sowing date could influence mulching dates, which in turn affects the occurrence dates of local peaks and the shape of harmonic regression curves. In this study, in the Ningxia Irrigation District (NID, Fig. S1) and Wuzhong City of Ningxia Province, mulching dates were earlier than in other cities (Fig. S13) due to the widespread cultivation of watermelon, which is mainly sown in March. Consequently, the performance exhibited a significant decrease (median F1change ≈ −50%) when using classifiers trained on data from other cities in 2020 to recognize PMF in the two cities (Scenario–ST) for 2019 and 2021.

Cross-regional generalization of the proposed framework

The cross-regional generalization of the newly proposed framework was tested in representative regions across China, including Aksu Prefecture, Songnen Plain, Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, and North China Plain, where PMF is widely distributed (Fig. 15). In these regions, the F1 values for PMF recognition exceeded 0.92, and the derived PMF spatial distributions matched well with the actual ones. The relatively higher accuracy compared to the Loess Plateau could be attributed to the flatter terrain and more uniformly distributed plots in these areas. In contrast, the complex terrain and fragmented plots on the Loess Plateau may lead to mixed pixels, negatively affecting PMF extraction accuracy. Overall, the proposed framework performed satisfactorily in PMF mapping across regions with diverse agro-climatic conditions, crop calendars, and terrain, indicating its great potential for national-scale PMF mapping in future work.

Advantages and uncertainties

In this study, we proposed a new framework for large-scale PMF mapping. This framework offers four main advantages: (1) We introduced two novel PMF indices (MBPMFI and BPMFI) for automatically generating training samples, significantly enhancing the efficiency of sample collection compared to field surveys and visual interpretation. (2) Temporally transferring pre-trained classifiers to map multi-year PMF distributions further facilitates the long-term PMF monitoring without the need of year-specific samples. (3) The hybrid design of combining index-based sample generation with machine learning addresses the over-reliance of traditional index methods on mulching-stage data, enabling the production of seamless PMF maps even in regions with partial mulching-stage data gaps (Fig. S14f). (4) Since the Sentinel-2 bands used for developing PMF indices (i.e., the blue, green, and red bands, which are functionally equivalent for this purpose) and for constructing input features for machine learning classifiers are consistent with those of Landsat archives, the proposed framework is also applicable to PMF mapping using Landsat data.

Although the new framework successfully identified PMF across different regions and years on the Loess Plateau of China, there still exists some room for improvement. First, although Sentinel-2 has a 5-day revisit cycle, clear-sky observations are still often limited in some regions, especially in southern China, due to inevitable cloud contaminations. The large-scale loss of images during the mulching stage could constrain the application of the proposed framework. To address this issue, more optical satellite imagery, such as Landsat-4/5/7/8/9, could be integrated to provide denser time-series observations in the future.

Second, this study primarily focused on transparent plastic films, but regional variations in plastic film thickness may influence PMF extraction accuracy. Previous studies have demonstrated that excessively thin plastic films are susceptible to interference from soil backgrounds18. This interference reduces the local peak reflectance of PMF in the blue band during the mulching stage, which in turn increases spectral similarity between PMF and Non-PMF. Such similarity was observed in Inner Mongolia (Fig. S5d) and Shanxi Province (Fig. S5f) in this study. Ultimately, this weakened spectral contrast hindered the ability of the RF classifier to distinguish between PMF and non-PMF, leading to lower extraction accuracy in these regions (Fig. 8a).

Finally, this study focused on evaluating temporal and spatiotemporal transferability of the RF classifier for PMF mapping. Due to the limitations of GEE platform, deep learning algorithms such as Deep Neural Network (DNN) and Convolution Neural Network (CNN), which exhibit better performance than the traditional supervised classifiers84,85, were not explored in this study. However, employing deep learning algorithms for PMF mapping presents challenges related to computational costs and the need for more training data77,86,87.

Data availability

The PMF-LP product generated in this study is available at https://zenodo.org/records/1336942680. The 10-m PMF distribution maps for the whole China (China-PMF-10) can be accessed from Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28528919.v382. The Sentinel-2 surface reflectance data was acquired from Google Earth Engine (available at https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/COPERNICUS_S2_SR_HARMONIZED). The GLC_FCS30D51 was downloaded from Zenodo data repository (https://zenodo.org/records/8239305). The CACD52 dataset can be accessed at https://zenodo.org/records/7936885. The CLCD53 product can be found at https://zenodo.org/records/4417810. The Google Earth high-resolution images were sourced from Google Earth Pro (v3.3.6) (https://earth.google.com/). The PMF census data was sourced from National Bureau of Statistics (https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/) and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (https://www.cnki.net/).

Code availability

The core codes used to generate the plastic-mulched farmland distribution maps are publicly available at https://github.com/zhaocheng0218/CHN_LoessPlateau_PMF_Maps.

References

Liu, E. K., He, W. Q. & Yan, C. R. ‘White revolution’ to ‘white pollution’—agricultural plastic film mulch in China. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 091001, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/9/9/091001 (2014).

Sun, D. et al. An overview of the use of plastic-film mulching in China to increase crop yield and water-use efficiency. Natl. Sci. Rev. 7, 1523–1526, https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwaa146 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. A review of plastic film mulching on water, heat, nitrogen balance, and crop growth in farmland in China. Agronomy-Basel 13, 2515, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13102515 (2023).

Yang, N. et al. Plastic film mulching for water-efficient agricultural applications and degradable films materials development research. Mater. Manuf. Process. 30, 143–154, https://doi.org/10.1080/10426914.2014.930958 (2015).

Yan, C. et al. Review of agricultural plastic mulching and its residual pollution and prevention measures in China (in Chinese). Journal of Agricultural Resources and Environment 31, 95–102, https://doi.org/10.13254/j.jare.2013.0223 (2014).

Zhang, J. et al. Influence of plastic film on agricultural production and its pollution control (in Chinese). Scientia Agricultura Sinica 55, 3983–3996, https://doi.org/10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2022.20.010 (2022).

Kumar, M. et al. Microplastics as pollutants in agricultural soils. Environ. Pollut. 265, 114980, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114980 (2020).

Gao, H. H. et al. Effects of plastic mulching and plastic residue on agricultural production: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 651, 484–492, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.105 (2019).

Lu, L., Di, L. & Ye, Y. A decision-tree classifier for extracting transparent plastic-mulched landcover from Landsat-5 TM images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 7, 4548–4558, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2014.2327226 (2014).

Veettil, B. K. et al. Remote sensing of plastic‐covered greenhouses and plastic‐mulched farmlands: Current trends and future perspectives. Land Degrad. Dev. 34, 591–609, https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4497 (2023).

Maselli, F. et al. Use of Sentinel-2 MSI data to monitor crop irrigation in Mediterranean areas. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 93, 102216, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2020.102216 (2020).

Weiss, M., Jacob, F. & Duveiller, G. Remote sensing for agricultural applications: A meta-review. Remote Sens. Environ. 236, 111402, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111402 (2020).

Phiri, D. et al. Sentinel-2 data for land cover/use mapping: A review. Remote Sens. 12, 2291, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12142291 (2020).

Gorelick, N. et al. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202, 18–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.06.031 (2017).

Tamiminia, H. et al. Google Earth Engine for geo-big data applications: A meta-analysis and systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 164, 152–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2020.04.001 (2020).

Pham-Duc, B. et al. Trends and applications of google earth engine in remote sensing and earth science research: A bibliometric analysis using scopus database. Earth Sci. Inform. 16, 2355–2371, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12145-023-01035-2 (2023).

Lu, L., Hang, D. & Di, L. Threshold model for detecting transparent plastic-mulched landcover using moderate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer time series data: a case study in southern Xinjiang, China. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 9, 097094, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JRS.9.097094 (2015).

Xiong, Y. et al. Large scale agricultural plastic mulch detecting and monitoring with multi-source remote sensing data: A case study in Xinjiang, China. Remote Sens. 11, 2088, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11182088 (2019).

Fu, C. et al. Timely plastic-mulched cropland extraction method from complex mixed surfaces in arid regions. Remote Sens. 14, 4051, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14164051 (2022).

Hao, P. et al. New workflow of plastic-mulched farmland mapping using multi-temporal Sentinel-2 data. Remote Sens. 11, 1353, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11111353 (2019).

Cheng, L. et al. Spatiotemporal variations of plastic-mulched cropland in Hexi Corridor using multi-source remote sensing data (in Chinese). Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 39, 124–131, https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.202303209 (2023).

Hasituya & Chen, Z. Mapping plastic-mulched farmland with multi-temporal Landsat-8 data. Remote Sens. 9, 557, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9060557 (2017).

Zheng, W. et al. Remote sensing recognition of plastic-film-mulched farmlands on Loess Plateau based on Google Earth Engine (in Chinese). Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery 53, 224–234, https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2022.01.025 (2022).

Lu, L., Tao, Y. & Di, L. Object-based plastic-mulched landcover extraction using integrated Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data. Remote Sens. 10, 1820, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10111820 (2018).

Zhao, C. et al. Plastic-mulched farmland recognition in Loess Plateau based on Sentinel-2 remote-sensing images (in Chinese). Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery 54, 180–192, https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2023.08.017 (2023).

Gao, Y. et al. FARM: A fully automated rice mapping framework combining Sentinel-1 SAR and Sentinel-2 multi-temporal imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 213, 108262, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2023.108262 (2023).

Zhang, H., Liu, W. & Zhang, L. Seamless and automated rapeseed mapping for large cloudy regions using time-series optical satellite imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 184, 45–62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2021.12.001 (2022).

Skakun, S. et al. Early season large-area winter crop mapping using MODIS NDVI data, growing degree days information and a Gaussian mixture model. Remote Sens. Environ. 195, 244–258, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.04.026 (2017).

Foody, G. M. & Arora, M. K. An evaluation of some factors affecting the accuracy of classification by an artificial neural network. Int. J. Remote Sens. 18, 799–810, https://doi.org/10.1080/014311697218764 (1997).

Wen, Y. et al. Mapping corn dynamics using limited but representative samples with adaptive strategies. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 190, 252–266, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2022.06.012 (2022).

Zhang, M. et al. A review of agricultural film mapping: current status, challenges, and future directions. Journal of Remote Sensing 5, 0395, https://doi.org/10.34133/remotesensing.0395 (2025).

Huang, H. et al. The migration of training samples towards dynamic global land cover mapping. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 161, 27–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2020.01.010 (2020).

Zang, Y. et al. Mapping rapeseed in China during 2017-2021 using Sentinel data: an automated approach integrating rule-based sample generation and a one-class classifier (RSG-OC). GISci. Remote Sens. 60, 2163576, https://doi.org/10.1080/15481603.2022.2163576 (2023).

Yang, G. et al. Automated in-season mapping of winter wheat in China with training data generation and model transfer. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 202, 422–438, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2023.07.004 (2023).

Pan, S. J. & Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 22, 1345–1359, https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2009.191 (2009).

Ma, Y. et al. Transfer learning in environmental remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 301, 113924, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2023.113924 (2024).

Wang, S., Azzari, G. & Lobell, D. B. Crop type mapping without field-level labels: Random forest transfer and unsupervised clustering techniques. Remote Sens. Environ. 222, 303–317, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2018.12.026 (2019).

Hu, Y. et al. An interannual transfer learning approach for crop classification in the Hetao Irrigation District, China. Remote Sens. 14, 1208, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14051208 (2022).

Orynbaikyzy, A., Gessner, U. & Conrad, C. Spatial transferability of random forest models for crop type classification using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. 14, 1493, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14061493 (2022).

Qadir, A. et al. A generalized model for mapping sunflower areas using Sentinel-1 SAR data. Remote Sens. Environ. 306, 114132, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2024.114132 (2024).

Qadir, A. et al. Estimation of sunflower planted areas in Ukraine during full-scale Russian invasion: Insights from Sentinel-1 SAR data. Science of Remote Sensing 10, 100139, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srs.2024.100139 (2024).

Beck, H. E. et al. High-resolution (1 km) Köppen-Geiger maps for 1901–2099 based on constrained CMIP6 projections. Sci. Data 10, 724, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02549-6 (2023).

Li, P. et al. Mapping planted forest age using LandTrendr algorithm and Landsat 5–8 on the Loess Plateau, China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 344, 109795, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109795 (2024).

Tang, X. et al. Analysis of precipitation characteristics on the loess plateau between 1965 and 2014, based on high-density gauge observations. Atmos. Res. 213, 264–274, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2018.06.013 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Spatially downscaling GCMs outputs to project changes in extreme precipitation and temperature events on the Loess Plateau of China during the 21st Century. Glob. Planet. Change 82-83, 65–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2011.11.008 (2012).

Wang, Y. P. et al. Multi-site assessment of the effects of plastic-film mulch on dryland maize productivity in semiarid areas in China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 220, 160–169, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2016.01.142 (2016).

Hasituya et al. Mapping plastic-mulched farmland by coupling optical and synthetic aperture radar remote sensing. Int. J. Remote Sens. 41, 7757–7778, https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2020.1763510 (2020).

You, N. et al. The 10-m crop type maps in Northeast China during 2017–2019. Sci. Data 8, 41, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00827-9 (2021).

Defourny, P. et al. Near real-time agriculture monitoring at national scale at parcel resolution: Performance assessment of the Sen2-Agri automated system in various cropping systems around the world. Remote Sens. Environ. 221, 551–568, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2018.11.007 (2019).

Han, J. et al. Annual paddy rice planting area and cropping intensity datasets and their dynamics in the Asian monsoon region from 2000 to 2020. Agric. Syst. 200, 103437, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2022.103437 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. GLC_FCS30D: the first global 30 m land-cover dynamics monitoring product with a fine classification system for the period from 1985 to 2022 generated using dense-time-series Landsat imagery and the continuous change-detection method. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 1353–1381, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-1353-2024 (2024).

Tu, Y. et al. A 30 m annual cropland dataset of China from 1986 to 2021. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 2297–2316, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-2297-2024 (2024).

Yang, J. & Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 3907–3925, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-3907-2021 (2021).

Feng, Q. et al. A dataset of remote sensing-based classification for agricultural plastic greenhouses in China in 2019 (in Chinese). China Scientific Data 6, https://doi.org/10.11922/noda.2021.0009.zh (2021).

Tong, X. et al. Global area boom for greenhouse cultivation revealed by satellite mapping. Nature Food 5, 513–523, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-00985-0 (2024).

Zhang, P. et al. A novel index for robust and large-scale mapping of plastic greenhouse from Sentinel-2 images. Remote Sens. Environ. 276, 113042, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2022.113042 (2022).

Zhou, C. et al. A novel approach: Coupling prior knowledge and deep learning methods for large-scale plastic greenhouse extraction using Sentinel-1/2 data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 132, 104073, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2024.104073 (2024).

You, N. et al. Rapid early-season maize mapping without crop labels. Remote Sens. Environ. 290, 113496, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2023.113496 (2023).

Zhang, C., Dong, J. & Ge, Q. IrriMap_CN: Annual irrigation maps across China in 2000–2019 based on satellite observations, environmental variables, and machine learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 280, 113184, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2022.113184 (2022).

Zhang, C., Zhang, H. & Tian, S. Phenology-assisted supervised paddy rice mapping with the Landsat imagery on Google Earth Engine: Experiments in Heilongjiang Province of China from 1990 to 2020. Comput. Electron. Agric. 212, 108105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2023.108105 (2023).

Zhang, H. K. & Roy, D. P. Using the 500 m MODIS land cover product to derive a consistent continental scale 30 m Landsat land cover classification. Remote Sens. Environ. 197, 15–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.05.024 (2017).

Hasituya et al. Monitoring plastic-mulched farmland by Landsat-8 OLI imagery using spectral and textural features. Remote Sens. 8, 353, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8040353 (2016).

Tucker, C. J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 8, 127–150, https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(79)90013-0 (1979).

Gitelson, A. A. et al. Remote estimation of canopy chlorophyll content in crops. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL022688 (2005).

Xiao, X. et al. Characterization of forest types in Northeastern China, using multi-temporal SPOT-4 VEGETATION sensor data. Remote Sens. Environ. 82, 335–348, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(02)00051-2 (2002).

Wang, L. & Qu, J. J. NMDI: A normalized multi-band drought index for monitoring soil and vegetation moisture with satellite remote sensing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL031021 (2007).

Rikimaru, A., Roy, P. S. & Miyatake, S. Tropical forest cover density mapping. Trop. Ecol. 43, 39–47 (2002).

Rasul, A. et al. Applying built-up and bare-soil indices from Landsat 8 to cities in dry climates. Land 7, 81, https://doi.org/10.3390/land7030081 (2018).

Jakubauskas, M. E., Legates, D. R. & Kastens, J. H. Harmonic analysis of time-series AVHRR NDVI data. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 67, 461–470 (2001).

Zhou, Q. et al. A novel regression method for harmonic analysis of time series. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 185, 48–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2022.01.006 (2022).

Zou, Q. et al. Deep learning based feature selection for remote sensing scene classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 12, 2321–2325, https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2015.2475299 (2015).

Wang, S. et al. A heterogeneous double ensemble algorithm for soybean planting area extraction in Google Earth Engine. Comput. Electron. Agric. 197, 106955, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2022.106955 (2022).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Zhang, X. et al. GLC_FCS30: Global land-cover product with fine classification system at 30 m using time-series Landsat imagery. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 2753–2776, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-2753-2021 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. Annual dynamics of global land cover and its long-term changes from 1982 to 2015. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 1217–1243, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-1217-2020 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. Towards automation of in-season crop type mapping using spatiotemporal crop information and remote sensing data. Agric. Syst. 201, 103462, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2022.103462 (2022).

Wijesingha, J., Dzene, I. & Wachendorf, M. Evaluating the spatial–temporal transferability of models for agricultural land cover mapping using Landsat archive. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 213, 72–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2024.05.020 (2024).

Belgiu, M. & Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 114, 24–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2016.01.011 (2016).

Sheykhmousa, M. et al. Support vector machine versus random forest for remote sensing image classification: A meta-analysis and systematic review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 13, 6308–6325, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2020.3026724 (2020).

Zhao, C. et al. PMF-LP: the first 10 m plastic-mulched farmland distribution map (2019–2021) in the Loess Plateau of China generated using training sample generation and classifier transfer method. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13369426 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Occurrence of macroplastic debris in the long-term plastic film-mulched agricultural soil: A case study of Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 831, 154881, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154881 (2022).

Niu, B. et al. China-PMF-10: a 10-m national map of plastic-mulched farmlands in China of 2020 using deep semantic segmentation. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28528919.v3 (2025).

You, N. & Dong, J. Examining earliest identifiable timing of crops using all available Sentinel 1/2 imagery and Google Earth Engine. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 161, 109–123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2020.01.001 (2020).

Zhong, L., Hu, L. & Zhou, H. Deep learning based multi-temporal crop classification. Remote Sens. Environ. 221, 430–443, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2018.11.032 (2019).

Wang, P., Fan, E. & Wang, P. Comparative analysis of image classification algorithms based on traditional machine learning and deep learning. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 141, 61–67, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2020.07.042 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. Towards interpreting multi-temporal deep learning models in crop mapping. Remote Sens. Environ. 264, 112599, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2021.112599 (2021).

Zhang, D. et al. A generalized approach based on convolutional neural networks for large area cropland mapping at very high resolution. Remote Sens. Environ. 247, 111912, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.111912 (2020).

Farr, T. G. et al. The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev. Geophys. 45, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005RG000183 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFD1900700), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52579046), and the “111 Project” (No. B12007) of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Cheng Zhao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Yadong Luo: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Xiangyu Chen: Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization. Linxian Jiang: Formal analysis, Validation. Zhao Wang: Resources, Supervision. Hao Feng: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Qiang Yu: Methodology, Supervision. Jianqiang He: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, C., Luo, Y., Chen, X. et al. A 10-m resolution dataset of plastic-mulched farmland distributions on the Chinese Loess Plateau (2019–2021). Sci Data 12, 2020 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06304-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06304-x