Abstract

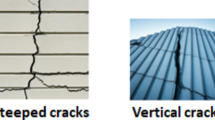

Visual inspection of civil infrastructure has traditionally relied on manual operations, characterized by high labor intensity, low efficiency, and limited scalability, which significantly constrains its effectiveness in modern maintenance and management scenarios. Although deep learning technologies have demonstrated remarkable potential for automation and precision, their practical implementation in real-world engineering contexts remains hindered by the scarcity of large-scale, high-quality annotated datasets. To address this challenge, this study constructs a UAV-based dataset of building surface defects, comprising 14,471 high-resolution images captured across six structural types and five representative defect categories from both urban and rural environments. The dataset includes various defect types such as cracks, abscission, leakage, corrosion, and bulging, recorded under diverse illumination and environmental conditions. Each image is annotated with standardized bounding boxes and systematically divided into training, validation, and testing subsets. This dataset provides a comprehensive, diverse, and publicly accessible benchmark for advancing multi-task research in defect detection, segmentation, and automated visual assessment of building surfaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

With deepening global economic integration and accelerating urbanization1, developing countries are driving the rapid expansion of construction activities2. With the increasing scale and complexity of buildings, the safety and quality inspection of building structures are facing increasingly severe challenges3. The identification and assessment of surface defects such as crack and leakage, which have a direct impact on the safety of public life and property, require urgent attention. According to international research data, 40% of the ten most fatal building collapse incidents worldwide were major safety accidents caused by structural defects in construction. This phenomenon highlights the importance of identification and early intervention of building defects. If building defects can be accurately identified and intervened at an early stage, the risk of major structural disasters can be significantly reduced, thus effectively safeguarding people’s lives and public safety. Furthermore, the diversification in the types of building structures, including steel, concrete and wood structures, further enhances the difficulty and complexity of detecting defects on the exterior surfaces of buildings4. Therefore, how to realize efficient and accurate detection of defects on the exterior surfaces of buildings with diverse structures is of great importance.

Currently, manual visual inspection is still the most commonly used means of defect identification5. This traditional approach relies on hiring skilled and experienced professionals to inspect the building and record relevant defect information6, which is time-consuming and labor-intensive. Variations in inspector experience can lead to inconsistent defect judgments, potentially causing severe safety incidents with irreversible human and economic loss. Therefore, it is imperative to develop novel approaches to enhance the efficiency of construction defect detection and reduce reliance on conventional manual visual inspection methods. In recent years, with significant advancements in artificial intelligence7,8,9,10, inspection systems integrating deep-learning-based computer vision algorithms11 and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)12 platforms have emerged as promising alternatives to traditional practices. These systems combine non-contact inspection capabilities13, high-resolution imaging technologies14, and the powerful feature extraction capacities of deep neural networks15, offering distinct advantages including enhanced detection efficiency, improved inspection accuracy, and reduced operational risk. Thus, there is an increasing demand for the integration of deep learning-based visual detection techniques and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in the field of construction defect inspection, aiming to substantially enhance both inspection accuracy and operational efficiency.

To address the challenge of enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of building defect detection, existing research has predominantly concentrated on methodological innovations. Contemporary deep learning-based defect detection approaches are largely grounded in classical architectures, including YOLO series16,17,18,19,20,21,22, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)23,24,25,26,27,28 and Faster R-CNN29,30. Among these methods, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) model has emerged as a particularly effective solution, achieving an optimized trade-off between detection accuracy and computational efficiency due to its single-stage architecture and lightweight design. Its modular architectural features enables customized improvements through the integration of advanced strategies such as attention mechanism31, feature pyramid optimization32 and dynamic convolutional kernel, making it highly suitable for defect detection in complex construction senvironments. For instance, Xu et al. developed a multi-objective real-time concrete crack and structural deformation detection model based on an improved YOLOv7 architecture, achieving a 4.53% improvement in the crack detection accuracy, and peak relative errors as low as 0.22% and 3.05% for concrete beam and slab deformation, respectively33. Lu et al.34 proposed a high-resolution defect detection method tailored for ceramic tile surfaces based on an enhanced YOLOv5 model, attaining an average detection accuracy of 96.73%. Cui et al.35 introduced the MHSA-YOLOv4 algorithm integrating Transformer-based mechanisms to identify concrete wind erosion in arid northwestern regions. The experimental results revealed strong performance, with an accuracy of 91.30%, precision of 91.52%, recall of 92.31%, and mAP of 0.89, outperforming baseline models such as YOLOv3 and YOLOv4. To further reduce computational overhead, Chen et al.36 proposed the CD-YOLOv8 model, a lightweight variant optimized for UAV-assisted bridge inspection tasks. This novel model outperformed YOLOv8n by 3.6% in accuracy and 15.79% in inference speed. Additionally, Karimi et al.37 addressed the need for automated monitoring of cultural heritage structures, applying the YOLO multi-classification model and the Mobile Net binary classifier to detect defects in Portuguese azulejo tiles. The dataset of over 5000 annotated tiles with cracks, pits, and glaze peeling, supported model optimization, achieving 72% and 97% accuracy, respectively, thereby validating the practical utility of deep learning techniques for heritage preservation. While enhanced YOLO models excel in structural defect detection, their real-world applicability remains limited by narrow training scopes. Most rely on task-specific data, leading to poor generalization across diverse scenarios. A comprehensive and diverse defect dataset is urgently required to overcome these limitations and enable robust, scalable deployment.

In constructing such datasets, researchers must overcome a series of technical challenges. To comprehensively capture the surface features of complex building structures, UAV platforms are commonly employed to acquire multiple-angle images, complemented by meticulous manual annotation of defect types. This process necessitates effective handling of critical issues such as variations in ambient lighting, consistency and completeness of multi-class annotations, and the assurance of data quality suitable for high-precision model training. Currently, several representative datasets have been developed in the field of construction defect detection. For instance, the CODEBRIM38 dataset, which focuses on concrete bridges defects, utilizes high-resolution imaging equipment mounted on drones and employs large focal length parameter settings to capture, images with resolutions up to 6,000 × 4,000 pixels emphasizing the multi-scale characteristics of fine bridge surface defects. However, it contains only 1590 images, falling short in terms of volume, scene diversity, defect taxonomy, and engineering practicality, thereby limiting its utility in broader construction contexts. Zhao et al.39 introduced CUBIT-Det, a high-resolution infrastructure defect dataset comprising 5,500 professionally annotated images. It has been systematically evaluated by 30 mainstream real-time detection algorithms, demonstrating strengths in zero shot transferability and engineering relevance. Nonetheless, CUBIT-Det still exhibits limitations in sample size and defect heterogeneity, covered only a few categories such as crack, spalling, and moisture. Moreover, the dataset is dominated by building scenarios (approximately 65%), but lacks fine-grained classification of building types. In contrast, the dataset presented in this study provides a more detailed classification, covers six typical building types, thus better supporting infrastructure defect detection across diverse scenarios. Flotzinger et al.40 introduced dataset dacl1k, which includes 1,474 uncropped images from real building inspections, classified into six categories (Crack, Spalling, Efflorescence, Rust, Bars Exposed, and No Damage). However, the dacl1k dataset is limited by its small size with a focus on bridges, and weak generalization, resulting in suboptimal model performance in real-world applications. Therefore, constructing a larger, more diverse dataset encompassing varied structure types and defect categories is crucial to overcoming these limitations and providing a robust foundation for future research.

To address the common limitations of existing building defect detection datasets, this study introduces MBDD202541, a large-scale, multi-scene dataset specially designed for infrastructure defect detection. Comprising 14,471 high-resolution image (up to 1280 × 720), the dataset covers six representative building structure types steel, reinforced concrete, wood, brick, masonry, and brick-concrete structures. Each image is meticulously labeled with five common types of building defects, including crack, leakage, corrosion, abscission, and bulge, providing a rich and high-quality data foundation for multi-scenario defect detection. This dataset is benchmarked using 35 leading object detection models, including Faster R-CNN29,30, YOLOv516, and YOLOv617, enabling a thorough evaluation of its adaptability and effectiveness in real-world inspection tasks. The findings validate the dataset’s practical applicability and its potential to address pressing challenges in building maintenance. The core contribution of this lies in the creation of a standardized dataset with broad coverage and high relevance to both academic research and industry practices. By enhancing the generalization ability and recognition accuracy of defect detection models, MBDD2025 provides a vital resource for advancing intelligent infrastructure maintenance, meeting the critical need for sustainable urban development and economic efficiency in the construction industry.

Furthermore, the MBDD2025 dataset and its detection framework are not limited to building façade defect identification but can also be extended to broader infrastructure safety assessment scenarios such as bridge structural health monitoring (SHM). By integrating deep learning–based visual detection results with structural response sensors and vibration monitoring systems, the proposed approach can provide intuitive spatiotemporal information on critical surface damages, including cracks and corrosion, thereby enabling continuous tracking and early warning of structural performance degradation. This cross-domain detection framework is conceptually aligned with the continuous bridge monitoring methodology proposed by Argentino et al.42, offering a feasible pathway toward the development of multimodal and intelligent monitoring systems.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

-

(a)

The MBDD2025 dataset systematically covers six typical building structure types (steel, reinforced concrete, brick-concrete, masonry, brick-wood, and wood), extending the structural diversity of existing datasets and supporting defect detection across varied building forms for maintenance applications.

-

(b)

It includes five high-frequency defect categories (crack, leakage, corrosion, abscission, bulge), enhancing cross-material applicability and enabling comprehensive detection strategies for repair and upkeep.

-

(c)

Benchmarking with 35 detection models identifies key challenges in building defect detection. The results guide future algorithm improvements and promote practical adoption in smart inspection and automated maintenance.

Methods

In this study, a comprehensive dataset named MBDD2025 was constructed and publicly released, encompassing a wide variety of building structures and defect types. The dataset comprises 14,471 images and includes six common structural categories: reinforced concrete, steel structures, masonry structures, brick-concrete structures, timber structures, and brick-wood structures, as well as five typical types of building defects: crack, leakage, corrosion, abscission, and bulge. The selection of structural and defect types is based on the prevalent forms and common pathologies found in urban and rural buildings across China, ensuring both representativeness and practical relevance.For instance, reinforced concrete and brick-concrete structures are extensively used in urban residential and public buildings, while timber and masonry structures are more commonly found in historical buildings, rural housing, and recreational facilities. Such a selection enables the dataset to cover materials and deterioration patterns representative of real-world conditions. The classification of defect types refers to industry standards such as the Manual for Prevention of Common Quality Defects in Building Engineering, supplemented by field observations of recurring defects throughout the building lifecycle, thereby enhancing the dataset’s engineering applicability and realism.

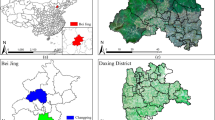

Data collection was conducted in Hefei City, Anhui Province, covering six major administrative regions: Shushan District, Baohe District, Yaohai District, Luyang District, Feixi County, and Feidong County. The site selection was based on a systematic assessment of Hefei’s urban development status and spatial structural characteristics, aimed at improving sample representativeness and the applicability of research outcomes. According to China Economic Net, in 2024, Hefei’s total construction output reached 617.4 billion CNY, with construction and installation investment totaling 245.8 billion CNY, and urban village redevelopment projects encompassing a cumulative 5.64 million square meters of expropriation area. These large-scale urban renewal activities provided abundant, authentic defect samples and representative scenarios for the study. As a newly emerging first-tier city supported by national development strategies, Hefei has undergone rapid urbanization in recent years, presenting a unique coexistence of new and old buildings, as well as diverse urban and rural morphologies. This complexity supports research into the distribution, causes, and evolution of building defects across different structural systems. Moreover, situated in the core area of the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, Hefei serves as a national comprehensive science center with active performance in economic development, population concentration, and infrastructure construction. Its architectural landscape includes a multilayered mix of historical districts, industrial plants, modern residential areas, and various public service facilities, offering a robust empirical foundation for building defect detection studies.

From a climatic perspective, Hefei is located in East China and features a typical subtropical humid monsoon climate, with an average annual precipitation of approximately 906 mm, concentrated mainly between May and July. The region experiences high humidity, significant temperature fluctuations, and cold, damp winters. These climatic conditions pose challenges to building durability, often leading to moisture infiltration, erosion, and subsequent defects such as cracking, abscission, and corrosion. The typical environmental characteristics of the region provide a complex and realistic backdrop for evaluating model adaptability and robustness under real-world conditions.

Regarding regional sampling strategy, Shushan and Luyang Districts, as central urban areas, are characterized by dense high-rise buildings and well-developed public infrastructure, representing typical urban cores. Baohe and Yaohai Districts encompass both older neighborhoods and newly developed residential areas, demonstrating a wide temporal and structural span. Feixi and Feidong Counties, located at the urban-rural fringe, preserve a substantial number of traditional brick-wood structures, self-built houses, and rural infrastructure such as schools, township hospitals, and cultural centers. The sampling framework, which combines urban centers with urban–rural transition zones, enables the construction of a comprehensive representation of structural types and defect distributions across various spatial scales, thereby enhancing the dataset’s generalizability and applicability.

In addition, the selected areas cover a wide range of functional uses, including residential, commercial, educational, transportation, and cultural buildings. The diverse and complex sampling environments not only enrich the dataset’s functional dimensions but also provide a solid data foundation for supporting multi-task and multi-scenario applications of detection models.

The MBDD2025 dataset construction workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1, encompassing the complete process from project planning and UAV-based image acquisition to image annotation and model training. To ensure representativeness and diversity, UAV-assisted photography was employed to systematically collect and annotate large-scale image data corresponding to the six structural categories and five defect types. Fig. 2 presents example images of the five typical defect types, which exhibit clear visual characteristics and authentic engineering contexts, thereby providing effective support for model training and evaluation in defect detection and classification tasks.

Example images from the dataset. The first column illustrates crack defects on building surfaces, the second column shows leakage defects, and the third column presents abscission defects in buildings. The fourth and fifth columns depict corrosion and bulge defects, respectively. The bounding boxes in the images indicate the locations of the building defects.

Data acquisition equipment

In this study, UAV remote sensing technology was employed to construct a comprehensive building defect dataset, aimed at enabling efficient and accurate identification of structural damage features. Data acquisition was conducted using the DJI Mini 4 K multi-rotor UAV platform, equipped with a state-of-the-art 1/1.3-inch CMOS sensor capable of generating high-quality aerial imagery at 4000 × 3000 pixels. The sensor is equipped with a 2.4 μm pixel size and an f/1.7 large-aperture lens, which significantly enhance imaging performance under complex lighting conditions and ensure image stability and fidelity across diverse weather and illumination scenarios.

Data collection

Given the high requirements for data scale and scene complexity in this study, six districts and counties in Hefei, China, were selected as the primary data acquisition areas. The selected regions encompass urban residential communities, rural building clusters, and public infrastructure such as parks, thereby providing a comprehensive representation of diverse building environments. All images were collected exclusively using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) equipped with 4K-resolution cameras. The UAVs operated at altitudes ranging from 5 to 25 meters and captured images at both oblique and vertical angles to ensure complete façade coverage and sufficient defect visibility. This broad spatial diversity ensures the dataset’s representativeness and variety in terms of architectural scenarios, which is critical for developing building defect detection models with strong generalization capabilities. Such diversity significantly enhances the adaptability of the models to complex and real-world environments. The geographical distribution of sampling locations is illustrated in Fig. 3, which provides a spatial layout of the selected regions and detailed sampling sites. This visualization aids in understanding the spatial coverage of the dataset and supports subsequent data analysis and model evaluation.

Among the six structural categories included in this study, reinforced concrete, steel, brick-concrete, and masonry structures are commonly used in residential and commercial buildings. However, due to the more standardized renovation and maintenance practices typically applied to commercial buildings, visible surface defects are less prevalent, resulting in a relative scarcity of relevant image data. Therefore, the data collection efforts in this study were primarily focused on residential areas. During the image acquisition process, the research team strictly adhered to relevant laws and regulations. All necessary reporting and approval procedures were completed in advance to ensure full legal compliance, thereby guaranteeing the legitimacy of the data collection process and the reliability of data sources. To ensure dataset diversity, UAV photography was conducted under various natural illumination conditions, including low-light, normal-light, and strong-light scenarios, to capture lighting variations representative of real-world environments. Extreme weather such as rain or heavy fog was avoided to maintain image clarity and data consistency.

To ensure a balanced distribution across different structural types, the research team paid special attention to the acquisition of data related to timber and brick-wood structures, which are underrepresented in existing public datasets. A differentiated sampling strategy was implemented, focusing on representative traditional buildings and public recreational areas within Hefei. Through field visits to selected locations and assessments based on building function and maintenance status, a large number of representative images capturing defects in brick-wood structures were collected, significantly enhancing the balance of structural types within the dataset. Compared to reinforced concrete buildings, surface defects in brick-wood structures are often less visually prominent. For example, defects such as spalling are less frequently observed with the naked eye. Therefore, the image collection process emphasized the detection and documentation of subtle and micro-scale defects.

In terms of imaging methodology, a standardized UAV-based data acquisition framework was established to ensure repeatability and coverage consistency. A horizontal UAV-based image capture approach was adopted. A flight algorithm based on photogrammetric path planning principles was designed to improve efficiency and coverage. Specifically, a zigzag flight pattern was employed, where the UAV flew in strip-like paths either vertically or horizontally, parallel to the building façades. This method improved the efficiency of image acquisition while enhancing the system’s ability to capture detailed structural features from multiple perspectives. Fig. 4 presents the flight strategy based on a vertical zigzag path. At each turning point, the UAV avoids sharp right-angle turns by executing smooth, rounded transitions. This path design reduces inertial shocks caused by abrupt maneuvers and effectively shortens the overall flight distance. Fig. 4(a) shows a front view of the zigzag trajectory along vertical strips, demonstrating effective image acquisition performance, particularly at low flight speeds. Fig. 4(b,c) provide schematic top and right views, respectively, illustrating the UAV’s movement and image capture along the planned path. Overlaps between adjacent images enhance image quality, with overlapping regions consistently annotated. The automated UAV system employing this energy-efficient path planning strategy significantly reduces labor costs for building-scene data collection and enhances operational efficiency.

Illustration of UAV flight path and image acquisition strategy. (a) Front view shows waypoints and building facades with a hover–shoot–move approach. (b) Top view highlights horizontal FoV overlap between adjacent waypoints for seamless coverage. (c) Right view depicts vertical FoV overlap and key geometric parameters, including waypoint spacing and camera coverage. (d) Sample images captured under varying lighting conditions.

Special attention was given to the effects of lighting variation on image quality and subsequent model performance during data collection. Accordingly, images were captured under both low-light and high-light conditions to enrich the dataset with diverse lighting scenarios. This approach improves the variability of the training data and enhances the model’s generalization capability and robustness in complex real-world environments. As shown in Fig. 4(d), the first row displays images taken under low-illumination conditions, simulating environments such as overcast days, early mornings, or late evenings. The second row shows images captured under strong lighting, corresponding to high-contrast scenes with intense sunlight and reflections. Incorporating lighting diversity enhances the model’s adaptability to brightness variations and provides a solid foundation for developing a more robust defect detection system. This UAV-based data acquisition framework, encompassing multiple flight patterns and illumination conditions, ensures that the collected images comprehensively represent diverse architectural and environmental contexts, thereby improving the overall reliability and applicability of the MBDD2025 dataset.

Data cleaning and enhancement

After completing image acquisition, data cleaning was a crucial step to ensure dataset quality and lay the foundation for subsequent annotation and model training. To address invalid images generated during collection, the study first performed image screening and elimination to improve dataset integrity. During UAV photography, some images failed to capture defect targets effectively or were invalid due to shooting errors; such images were identified and removed. Meanwhile, blurred or defocused images caused by UAV high-speed movement or abrupt stops were also excluded to avoid interference in subsequent analysis. Statistical analysis revealed a significant class imbalance within the dataset, with the bulge defect category severely underrepresented, containing only 98 samples. This imbalance could restrict model performance and optimization capability. To alleviate this issue and achieve a more balanced sample distribution, data augmentation techniques were applied. By performing 360° rotation and cropping on the original bulge images, the number of samples was increased tenfold to 980, thereby enhancing dataset diversity and representativeness. However, such synthetic augmentation may not fully capture real-world variations in lighting, viewpoint, and environmental context, potentially increasing the risk of overfitting. To mitigate this, validation-based monitoring and early stopping were employed during model training. This augmentation strategy provided more reliable data support for model optimization.

In future work, we plan to further refine the data cleaning pipeline by incorporating automated defect detection and quality assessment algorithms to identify low-quality or redundant samples more efficiently. Additionally, more extensive real-world image acquisition campaigns will be conducted to expand underrepresented defect categories and enhance the dataset’s overall diversity and realism.

Finally, after several rounds of rigorous screening and data enhancement, the dataset MBDD2025 was refined from an initial 19213 images to the current 14471 high-quality images, each labeled with a clear target defect. The statistical distribution of architectural defects can be seen in Table 1. These steps have significantly improved the dataset’s completeness, utility, and overall quality, ensuring a strong foundation for subsequent data annotation, model training, and analysis.

Data labeling

After the completion of data cleaning and augmentation, the data labeling process was immediately initiated. The Pascal VOC43 format was selected as the output format for annotation files, given its wide adoption in computer vision, particularly for object detection tasks. Prior to annotation, the clear and consistent criteria for defect identification was established through extensive discussion, aiming to minimize subjectivity and ensure labeling consistency. Specific guidelines were emphasized, including the requirement that each target defect be fully enclosed within a symmetrical bounding box, with no overlaps between boxes, and that all visible defects in each image be comprehensively annotated to avoid omissions. To further reduce human bias and improve annotation accuracy, each team member was assigned to label one or two specific defect categories. The annotations were subsequently cross-validated among team members and reviewed by industry experts, ensuring the accuracy, consistency, and reliability of the labeled data. All annotations in the MBDD2025 dataset were conducted using the Computer Vision Annotation Tool (CVAT), a robust and open-source platform widely used for object detection, image segmentation, and key point localization tasks. CVAT supports multi-user collaboration and offers an efficient, web-based interface for managing and executing large-scale annotation projects. In this study, the labeled outputs were exported in XML files conforming to the Pascal VOC43 standard, ensuring both interoperability and compatibility with mainstream deep learning frameworks. As illustrated in Fig. 5(a), the annotation interface displays color-coded bounding boxes that distinguish different defect types, while the information panel on the right provides real-time statistics of the annotated targets within each image. Fig. 5(b) shows a sample XML annotation file, which records critical metadata including the image filename, defect category, and the coordinates of each bounding box, thereby establishing a structured and standardized foundation for subsequent model training and evaluation.

The schematic diagram of the annotation platform and the annotation file: (a) is the annotation page of the CVAT platform, and the rectangular boxes of different colors indicate different defects; (b) The XML file contains the basic information of the picture and the coordinates of the rectangular box.

Defect location distribution

In object detection tasks, the spatial distribution of targets within an image is one of the key factors influencing model performance. The positional distribution characteristics of targets are directly related to the model’s capacity to perceive spatial structures, specifically its ability to model the spatial layout and relative positional relationships among targets. When targets exhibit substantial positional deviation within the image, a detection model with strong spatial robustness can still accurately localize and recognize them, demonstrating adaptability to displaced targets.

Taking building defect detection as an example, defects in real-world scenarios are typically distributed sparsely and irregularly throughout the image. Therefore, a model capable of accurately detecting these scattered targets exhibits strong robustness and flexibility in handling variations in target locations. Moreover, the spatial distribution of targets is closely associated with the model’s generalization ability. If the target distribution in the training data is highly concentrated or biased, the model is more likely to produce false positives or miss detections when encountering targets in previously unseen scenes with significantly different spatial patterns, thereby compromising its generalization performance.

Fig. 6 illustrates the spatial distribution of defect targets in the MBDD2025 dataset. Overall, the defects are relatively evenly distributed across the image area, yet a certain degree of aggregation is observed near the image center. This phenomenon arises because most defects tend to appear in the central regions of the captured scenes. While such a distribution can facilitate the model’s learning of typical spatial features, it may also introduce a central bias, potentially reducing detection performance for defects located near image boundaries. To mitigate this effect, future work will adopt multi-view and multi-angle data acquisition strategies to achieve a more balanced spatial distribution and enhance model generalization.

Data Records

The MBDD2025 dataset constructed in this study has been publicly released on the open-access scientific data platform Zenodo41, https://zenodo.org/records/15622584, to facilitate research and development in the field of building defect detection. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the dataset adopts a hierarchical folder structure, including the Annotations folder containing XML files in Pascal VOC43 format that provide bounding box coordinates and defect category information for each image; the JPEGImages folder, which contains the original high-resolution images named correspondingly to the annotation files; the Labels folder containing YOLO-format.txt files with normalized annotation information for direct use in YOLO-based models; and the README.md file, which details data composition, usage instructions, and citation information. This dataset not only offers rich diversity and practical application value but is also directly compatible with training YOLO and Faster R-CNN models. Researchers can access the dataset via the above DOI link.

Technical Validation

In order to ensure the quality of the training dataset, the original images were subjected to a rigorous screening process prior to model training. The filtered images were subsequently annotated by team members, and the corresponding XML annotation files were generated. Since the initial model training was conducted using YOLOv8n18, the XML files were converted into YOLO-format TXT files. Subsequently, the raw images, XML files, and TXT files were organized and compiled to form the complete MBDD2025 dataset. Before training, the dataset was divided into three subsets: 70% for training, 20% for validation, and 10% for testing. To ensure effective model training, it was critical to maintain a sufficiently large training set.

Following dataset preparation, model training was carried out. All experiments were conducted on a computing platform equipped with a 15-core vCPU Intel® Xeon® Platinum 8474 C processor and an RTX 4090D GPU. Fig. 8-1 illustrates the training workflow. The input images were first resized to a fixed resolution (e.g., 640 × 640) and normalized to a range of 0–1. Next, the CSP Darknet44 deep convolutional network was used to extract multi-scale features, capturing information at various semantic levels. Feature fusion was performed using a combination of Feature Pyramid Network (FPN)45 and Path Aggregation Network (PAN)46 structures to enhance the model’s ability to detect both large and small objects. The model then produced outputs for object class, bounding box location, and confidence scores. Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS)47 was applied to eliminate redundant bounding boxes, retaining only the optimal predictions and yielding clear, non-overlapping detection results. Finally, as shown in Fig. 8-2, the model was evaluated and benchmarked by analyzing the detection outcomes and assessing prediction accuracy. Furthermore, 35 state-of-the-art detection models were trained and evaluated on the MBDD2025 dataset to comprehensively validate its accuracy and applicability.

Evaluation metric

Precision (P), Recall (R), and Average Precision (AP) are widely used performance evaluation metrics in infrastructure defect detection. Precision (P) measures the accuracy of the detection results, representing the proportion of predicted defective targets that are actually defective. Recall (R) assesses the completeness of detection, indicating the proportion of actual defects that are successfully identified by the model. The mathematical definitions of these two metrics are presented below.

In this study, TP refers to a correctly detected defective instance, FP denotes a non-defective instance that is incorrectly identified as defective, and FN indicates a defective instance that is not detected. A detection is classified as a true positive (TP) if the Intersection over Union (IoU) between the predicted and actual bounding boxes exceeds a predefined threshold (Nt); otherwise, it is considered a false positive (FP). Undetected true defects are recorded as false negatives (FN).

The area under the precision-recall curve (AUC-PR) is a key metric for evaluating the performance of a target detection model, as it provides a comprehensive reflection of both false positives and false negatives across varying IoU thresholds. Similarly, Average Precision (AP) aggregates the model’s detection performance into a single value by calculating the weighted mean of precision at all recall levels along the PR curve, thereby enabling comparisons across different models. Since this study focuses on multi-class defect detection, the mean Average Precision (mAP) is computed by averaging the AP values for each category. The formulas for calculating AP and mAP are as follows, where APk represents the average precision for the k-th category, and n denotes the total number of categories.

Analysis of training results

In the initial phase of this study, YOLOv8n was selected as the baseline model for dataset validation. As the smallest and fastest variant in the YOLOv8 family, YOLOv8n significantly reduces computational costs while maintaining competitive detection accuracy, making it well-suited for real-time and efficiency-critical defect detection tasks. Given the need to balance detection performance with computational efficiency, YOLOv8n was ultimately employed for training and evaluation on the MBDD2025 dataset.

Model training commenced immediately following dataset partitioning. The training configuration included 100 epochs, an input image size of 640, a batch size of 32, and 12 worker threads. Training outcomes are presented in Fig. 9, illustrating the progression of key loss functions and performance metrics across both training and validation phases. The first row displays box loss, classification loss (cls loss), distribution focal loss (DFL loss), precision, and recall on the training set, while the second row presents the corresponding metrics on the validation set. As training progressed, all three loss values consistently decreased, indicating improved performance in bounding box regression, classification, and distribution learning. Simultaneously, evaluation metrics including precision, recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95 steadily increased and eventually stabilized, demonstrating that the model’s detection capability improved continuously and converged. Overall, the training process was stable, with no signs of overfitting or significant performance fluctuations.

The final training results are shown in Fig. 10. Fig. 10(a) presents the line graphs of mAP, recall, and precision across different defect categories. The model achieved an overall precision of 0.858, recall of 0.808, mAP@0.5 of 0.867, and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.486, indicating strong overall detection performance. Specifically, the model demonstrated excellent performance on the leakage and bulge categories, with mAP@0.5 values of 0.958 and 0.898, respectively. In contrast, the crack and abscission categories exhibited relatively lower accuracy, which can be attributed to their complex morphological characteristics such as irregular shapes, low contrast, and fine-grained textures that make accurate localization and classification more challenging. These findings suggest that refining the dataset and incorporating texture-aware adaptive attention mechanisms could further enhance detection accuracy. Fig. 10(b) illustrates the distribution of labeled instances across defect categories in the MBDD2025 dataset. Crack and abscission defects were the most frequently labeled, consistent with their high occurrence in real-world structures, while leakage and corrosion had fewer annotations, and bulge had the fewest, reflecting its lower frequency in practice.

After training, the model was evaluated on the test set to assess its detection performance. Representative results are shown in Fig. 10(c), where the model successfully identified various types of defects, including crack, leakage, abscission, corrosion, and bulge, by drawing bounding boxes and assigning class labels with confidence scores. The model performed reliably on leakage, abscission, and corrosion, achieving accurate localization and high confidence. While detection confidence for visually complex or ambiguous categories such as crack and bulge was slightly lower, the model still exhibited robust performance. Overall, YOLOv8n demonstrated strong defect detection capabilities on the MBDD2025 dataset, providing a solid foundation for subsequent tasks involving defect identification and evaluation.

Comparative analysis with existing datasets

To comprehensively describe the proposed MBDD2025 dataset, this study conducts a comparative analysis with two representative and publicly available datasets in the field of building defect detection: CODEBRIM38 and CUBIT-Det39. Table 2 presents a detailed comparison among the three datasets. Although MBDD2025 does not have an advantage in terms of image resolution, it demonstrates significant strengths in several other aspects.

Firstly, MBDD2025 contains 14,471 images, which is approximately 2.5 times the number in CUBIT-Det and more than 9 times that of CODEBRIM, thus providing a significantly larger data volume. Secondly, unlike CODEBRIM and CUBIT-Det, which primarily focus on a limited range of defect types such as crack, corrosion, and spalling, MBDD2025 covers a broader spectrum of structural defects, including crack, leakage, abscission, corrosion, and bulge. This contributes to greater diversity and practical applicability of the dataset. Furthermore, MBDD2025 involves a wider variety of structural materials, including concrete, steel structures, masonry, brick masonry, timber structures, and hybrid timber-brick structures. In contrast, CODEBRIM and CUBIT-Det are mainly concentrated on concrete materials, resulting in a relatively narrow material dimension.

In terms of experimental validation, the CODEBRIM dataset has primarily been evaluated using a limited number of neural network architectures, such as Meta QNN48 and Efficient Neural49. Although these methods show certain effectiveness for specific tasks, the limited number of models restricts the generalization of the results. As a result, the performance of the dataset under different deep learning models cannot be fully demonstrated. In comparison, the CUBIT-Det dataset features more representative and diverse experimental designs. Researchers employed a variety of mainstream object detection models, including the ResNet algorithm series29,30 and MobileNet50, PP YOLO51, PP YOLOv252, PPYOLOE53,PPYOLOEb53,YOLOX54,YOLOv721,YOLOv617 and YOLOv516, to conduct systematic and comprehensive evaluations. By performing comparative experiments under multiple model architectures, CUBIT-Det not only enhances the credibility of its results but also provides practical benchmark data for future studies.

In this study, we further expanded the range of evaluation models. To verify the effectiveness of the constructed dataset, we adopted multiple versions of the YOLO model from YOLOv5 to YOLO1119, as well as the classical two-stage detection model Faster R CNN. By conducting experiments on models with different architectural characteristics and detection mechanisms, we improved the representativeness of the evaluation. This also contributes to a comprehensive understanding of the dataset’s adaptability and performance across various mainstream object detection frameworks, thereby offering a solid and extensive reference for researchers in related fields.

To validate the effectiveness and superiority of the constructed dataset, the YOLOv8n model was trained and evaluated on the public CODEBRIM and CUBIT-Det datasets, as well as the proposed MBDD2025 dataset. Prior to training, key hyperparameters such as the number of epochs, input image size, batch size, and number of worker threads were kept consistent across all experiments to eliminate confounding factors. The experimental results are summarized in Table 3. Compared to CODEBRIM, which achieved an mAP@0.5 of 24.9% and an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 11.8%, and CUBIT-Det, which reported an mAP@0.5 of 73.7% and an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 45.9%, MBDD2025 demonstrated significantly higher performance. Specifically, it achieved an mAP@0.5 of 86.7% and an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 48.6%. The precision and recall scores also reached 85.8% and 80.8%, respectively. These results strongly demonstrate that MBDD2025 provides higher image quality, more accurate annotations, and greater task adaptability for building defect detection. Therefore, it serves as a valuable resource for training object detection models and improving their performance, with strong practical value and broad applicability.

Comparative analysis of dataset quality and model improvement

To comprehensively evaluate the relative impact of dataset quality and model architecture improvements on object detection performance, this study conducts a systematic experimental comparison on two representative datasets: the publicly available CUBIT-Det39 dataset and the proposed high-quality architectural defect detection dataset, MBDD2025. For model selection, four versions of the YOLO series16,17,18,19,20,21,22, widely adopted lightweight object detection algorithms, are chosen, namely YOLOv8n18, YOLOv9t22, YOLOv10n20, and the latest version YOLO11n19, covering a range of architectural evolutions from earlier to most recent models. All experiments were conducted under a unified training strategy and evaluation pipeline. The evaluation metrics include recall, precision, mean Average Precision at IoU threshold 0.5 (mAP@0.5), and the averaged metric across thresholds (mAP@0.5:0.95). The corresponding experimental results are illustrated in Fig. 11.

As shown in Fig. 11(a), across all four model configurations, the MBDD2025 dataset consistently yields significantly higher recall rates compared to CUBIT-Det, maintaining a stable performance around 0.80. This indicates that the MBDD2025 dataset enhances the model’s capability to detect true positive instances. In contrast, the recall rates of CUBIT-Det fluctuate considerably, ranging only from 0.63 to 0.68, suggesting limitations in terms of annotation completeness and target distribution balance.

Regarding the precision metric illustrated in Fig. 11(b), MBDD2025 also demonstrates a slight advantage over CUBIT-Det, with an average precision around 0.85, whereas CUBIT-Det remains at approximately 0.75. This suggests that MBDD2025 not only improves detection capabilities but also effectively reduces the number of false positives.

The superiority of MBDD2025 is even more evident in the comprehensive performance metrics mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95. As shown in Fig. 11(c), MBDD2025 achieves mAP@0.5 values consistently ranging from 0.86 to 0.88 across all model versions, whereas CUBIT-Det scores noticeably lower, between 0.68 and 0.75. This underscores the significant performance gain achievable through training on high-quality data, enabling improved average recognition across object classes. Furthermore, in the stricter evaluation metric mAP@0.5:0.95, shown in Fig. 11(d), MBDD2025 continues to exhibit superior and stable performance, outperforming CUBIT-Det by approximately 0.04 to 0.05 across all model versions. This trend further validates the positive impact of MBDD2025’s data diversity, class balance, and precise annotations on the model’s generalization capability.

The core reason for the observed performance gap lies in the fact that MBDD2025 not only contains a significantly larger number of images than CUBIT-Det, but also encompasses a broader range of real-world architectural defect scenarios. These include various structural materials, complex lighting conditions, multi-angle views, and diverse environmental contexts. Such characteristics substantially enrich the distribution of training samples, effectively mitigating the risk of model overfitting and enhancing robustness and generalization under complex conditions.

In summary, the experimental results lead to a clear conclusion: dataset quality and representativeness exert a significantly greater influence on object detection performance than the incremental improvements brought by model architecture upgrades from YOLOv8 to YOLO11. While continuous advancements in model design, such as more efficient feature extractors and improved loss functions, do contribute to performance gains, the quality and construction of the training dataset play a more fundamental and direct role in determining detection effectiveness. Therefore, the findings of this study further reinforce the data-centric research paradigm, highlighting that in practical applications and research development, improving dataset quality often yields more substantial system-level performance enhancements than solely relying on architectural innovations.

Evaluation of the dataset’s generalization capability

To comprehensively assess the adaptability and accuracy of the proposed MBDD2025 dataset in the task of building defect detection, we conducted extensive experiments using 35 mainstream object detection models. These models include various versions of the YOLO framework from YOLOv5 to YOLO11 as well as two representative Faster R-CNN29,30 architectures utilizing ResNet50 and ResNet101 as backbone networks.

As shown in Table 4, the YOLO series demonstrated consistently strong performance across both key evaluation metrics: mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95. Notably, models such as YOLOv10-x, YOLOv10-b, and YOLO11-x achieved mAP@0.5 scores exceeding 89%, with the highest mAP@0.5:0.95 reaching 53.3%. These models also achieved high AP scores in critical defect categories such as crack, leakage, and corrosion. These results suggest that the YOLO framework exhibits a strong ability to generalize across complex architectural structures and diverse defect morphologies, indicating significant advantages in fine-grained object detection tasks.

The YOLO (You Only Look Once) family represents a class of single-stage detectors characterized by end-to-end prediction capabilities. These models achieve high accuracy while maintaining fast inference speed and efficient deployment, making them particularly well-suited for real-time and high-throughput engineering applications. With ongoing architectural improvements in recent iterations, YOLOv9 through YOLO11 have integrated advanced components such as PGI-GELAN backbones and CNN-Transformer detection heads. These enhancements significantly improve the models’ sensitivity to small objects and low-contrast defects, leading to better adaptability and robustness in challenging visual environments.

In contrast, Faster R-CNN a classical two-stage detection framework while historically effective, underperformed relative to the YOLO series in this study. Specifically, Faster R-CNN with ResNet50 and ResNet101 achieved mAP@0.5 scores of 83.9% and 82.9%, respectively, with corresponding mAP@0.5:0.95 values of only 42.4% and 41.1%. In categories such as crack and abscission, the AP scores dropped to as low as 29.9% and 41.1%, indicating a limitation in detecting small objects within complex backgrounds.

It is worth highlighting that despite substantial architectural and backbone differences among the tested models, the MBDD2025 dataset consistently exhibited high compatibility and detection accuracy. This outcome reflects the overall quality of the dataset in terms of object distribution, image clarity, and annotation precision. For example, multiple models including YOLOv9 and YOLOv10 achieved AP values exceeding 76% across all six defect categories, underscoring the dataset’s strong representativeness and training value. This makes it a valuable benchmark for algorithm development and evaluation in applications such as building safety assessment and structural health monitoring.

In summary, the YOLO series outperformed the traditional Faster R-CNN models in both detection performance and practical applicability. More importantly, the successful deployment of the MBDD2025 dataset across 35 different detection models strongly validates its high quality and generalization capacity. This provides a solid data foundation and benchmark reference for future research and real-world deployment of intelligent building inspection systems.

Analysis of detection variability and evaluation of dataset robustness

To comprehensively evaluate the detection performance of the MBDD2025 dataset across different models, we selected the top-performing models for each defect category from a total of 35 trained models. These models were used to detect defects on the same test image, and the results were visualized for comparative analysis. As illustrated in Fig. 12, the detection outcomes of five representative defect types under different models are presented to analyze the variation in model responses to the same target and further reveal intrinsic characteristics of the dataset.

It can be observed that the detection results for the same image vary significantly across models in terms of bounding box position, size, and confidence scores. For defects such as crack and abscission, which often feature ambiguous boundaries and irregular shapes, all models generally succeed in identifying the primary defective areas. However, noticeable differences arise in localization accuracy and confidence scores. Some models exhibit redundant detection or multiple bounding boxes for the same defect, particularly in scenarios involving complex textures or uneven lighting. For instance, in crack detection, YOLOv8-m, YOLO11-s, and YOLOv7-x all successfully localize the defect region, yet the deviation of bounding boxes and fluctuations in confidence scores reflect variations in their ability to learn fine-grained features. Similarly, in abscission detection, YOLO11-x, YOLO11-l, and YOLOv9-c achieve consistent localization of the main defect region with confidence scores varying within a narrow range, though YOLOv9-c produces an additional bounding box, underscoring the uncertainty caused by vague defect boundaries.

In detecting corrosion and leakage, both characterized by more complex textures, models show more pronounced differences in edge delineation and region segmentation. Some models prioritize color and texture variations for region determination, while others are more prone to background interference, leading to missed detections or false positives and resulting in greater variance in confidence scores. For example, in corrosion detection, YOLOv9-s and YOLOv9-m demonstrate stable performance, whereas YOLOv8-s is affected by advertising elements in the background, reducing detection accuracy. Similarly, in leakage detection, YOLO11-l, YOLO11-m, and YOLOv5-x display notable disparities in their confidence levels.

Furthermore, in bulge defect detection, although the identified regions are largely consistent across models, the confidence scores still vary considerably. This suggests discrepancies in model sensitivity when dealing with structural changes that lack strong texture features. Overall, the results highlight two core characteristics of the MBDD2025 dataset.

-

(a)

The inherent complexity and diversity of defect types lead to differentiated responses across models in terms of boundary recognition and confidence estimation.

-

(b)

The high quality of image acquisition, annotation precision, and comprehensive scene coverage significantly enhances the dataset’s capability for evaluating model generalization in complex scenarios. These distinctions not only increase the training challenge for detection models but also substantiate the value and practical potential of MBDD2025 as a benchmark dataset in the field of building defect detection.

Data availability

The dataset supporting this study has been deposited in the Zenodo repository and is available at https://zenodo.org/records/15622584.

Code availability

All deep learning models used in this study are based on official open-source implementations available on GitHub. The YOLO model is accessible at https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics, and the Faster R-CNN implementation is based on the MMDetection framework at https://github.com/open-mmlab/mmdetection. The results can be reproduced by applying the hyperparameters specified in the manuscript and using the provided dataset and pretrained weights, without any modifications to the original model architectures.

References

Fu, C., Deng, T. & Zhang, Y. Boosted efficiency and unsaturated material stock growth in China’s megacities: Accelerating as urbanization approaches 80%. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 203, 107417, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2024.107417 (2024).

Wei, G., He, B.-J., Liu, Y. & Li, R. How does rapid urban construction land expansion affect the spatial inequalities of ecosystem health in China? Evidence from the country, economic regions and urban agglomerations. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 106, 107533, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2024.107533 (2024).

Ma, G., Wu, M., Wu, Z. & Yang, W. Single-shot multibox detector- and building information modeling-based quality inspection model for construction projects. Journal of Building Engineering 38, 102216, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102216 (2021).

Woo, H.-J., Hong, W.-H., Oh, J. & Baek, S.-C. Defining Structural Cracks in Exterior Walls of Concrete Buildings Using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Drones 7, 149, https://doi.org/10.3390/drones7030149 (2023).

Noel, A. B. et al. Structural Health Monitoring Using Wireless Sensor Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 19, 1403–1423, https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2017.2691551 (2017).

Kong, Q., Allen, R. M., Kohler, M. D., Heaton, T. H. & Bunn, J. Structural Health Monitoring of Buildings Using Smartphone Sensors. Seismological Research Letters 89, 594–602, https://doi.org/10.1785/0220170111 (2018).

Abu Dabous, S., Ait Gacem, M., Zeiada, W., Hamad, K. & Al-Ruzouq, R. Artificial intelligence applications in pavement infrastructure damage detection with automated three-dimensional imaging – A systematic review. Alexandria Engineering Journal 117, 510–533, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2024.11.081 (2025).

Kyu Shin, H., Young Kim, H. & Hyo Lee, S. Target Detection Algorithm in Crime Recognition Using Artificial Intelligence. Computers, Materials & Continua 71, 809–824, https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2022.021185 (2022).

Tong, X., Huang, X. & Li, Z. 3D Target Detection Algorithm of Laser Point Cloud Based on Artificial Intelligence. Procedia Computer Science 247, 335–343, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2024.10.039 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Chow, C. L. & Lau, D. Artificial intelligence-enhanced non-destructive defect detection for civil infrastructure. Automation in Construction 171, 105996, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2025.105996 (2025).

Liu, W. et al. Automatic tile position and orientation detection combining deep-learning and rule-based computer vision algorithms. Automation in Construction 171, 106001, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2025.106001 (2025).

Yiğit, A. Y. & Uysal, M. Automatic crack detection and structural inspection of cultural heritage buildings using UAV photogrammetry and digital twin technology. Journal of Building Engineering 94, 109952, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.109952 (2024).

Mustonen, J. et al. Non-contacting laser-ultrasonic fouling detection on steel pipes. Ultrasonics 151, 107617, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultras.2025.107617 (2025).

Haqiq, N. et al. Mine 4.0-mineCareerDB: A high-resolution image dataset for mining career segmentation and object detection. Data in Brief 57, 110976, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2024.110976 (2024).

Khan, Z. et al. Optimizing precision agriculture: A real-time detection approach for grape vineyard unhealthy leaves using deep learning improved YOLOv7 with feature extraction capabilities. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 231, 109969, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2025.109969 (2025).

ultralytics/yolov5: v4.0 - nn.SiLU() activations, Weights & Biases logging, PyTorch Hub integration v. v4.0 (Zenodo, 2021).

Li, C. et al. YOLOv6: A Single-Stage Object Detection Framework for Industrial Applications. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2209.02976 (2022).

Ultralytics. YOLOv8.

Ultralytics. Ultralytics YOLO11.

Wang, A. et al. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.14458 (2024).

Wang, C.-Y., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H.-Y. M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors (2022).

Wang, C.-Y., Yeh, I.-H. & Liao, H.-Y. M. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.13616 (2024).

El Bergui, A., Porebski, A. & Vandenbroucke, N. A lightweight spatial and spectral CNN model for classifying floating marine plastic debris using hyperspectral images. Marine Pollution Bulletin 216, 117965, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.117965 (2025).

Ishengoma, F. S. & Lyimo, N. N. Ensemble model for grape leaf disease detection using CNN feature extractors and random forest classifier. Heliyon 10, e33377, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33377 (2024).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. (Curran Associates, Inc.).

Shen, X. et al. Accurate machine vision identification of GCHD symptom using a self-attention-based CNN model with adaptive fish separation. Smart Agricultural Technology 11, 100871, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atech.2025.100871 (2025).

Wang, Y., Li, D., Li, L., Sun, R. & Wang, S. A novel deep learning framework for rolling bearing fault diagnosis enhancement using VAE-augmented CNN model. Heliyon 10, e35407, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35407 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Optimization of automated garbage recognition model based on ResNet-50 and weakly supervised CNN for sustainable urban development. Alexandria Engineering Journal 108, 415–427, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2024.07.066 (2024).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition (2015).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. in 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 770–778.

Li, T. & Zhao, Q. AE-YOLO: An Improved YOLOv7 based on Attention Enhancement for Rail Flaw Detection. IFAC-PapersOnLine 56, 7638–7643, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2023.10.1162 (2023).

Tang, Y., Yang, X., Wang, N., Song, B. & Gao, X. Person Re-Identification with Feature Pyramid Optimization and Gradual Background Suppression. Neural Networks 124, 223–232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2020.01.012 (2020).

Xu, G., Yue, Q. & Liu, X. Real-time multi-object detection model for cracks and deformations based on deep learning. Advanced Engineering Informatics 61, 102578, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2024.102578 (2024).

Lu, Q., Lin, J., Luo, L., Zhang, Y. & Zhu, W. A supervised approach for automated surface defect detection in ceramic tile quality control. Advanced Engineering Informatics 53, 101692, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2022.101692 (2022).

Cui, X. et al. Deep learning for intelligent identification of concrete wind-erosion damage. Automation in Construction 141, 104427, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104427 (2022).

Chen, Q. & Jiang, X. A portable real-time concrete bridge damage detection system. Measurement 240, 115536, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115536 (2025).

Karimi, N., Mishra, M. & Lourenço, P. B. Deep learning-based automated tile defect detection system for Portuguese cultural heritage buildings. Journal of Cultural Heritage 68, 86–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2024.05.009 (2024).

Mundt, M., Majumder, S., Murali, S., Panetsos, P. & Ramesh, V. Meta-learning Convolutional Neural Architectures for Multi-target Concrete Defect Classification with the COncrete DEfect BRidge IMage Dataset. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1904.08486 (2019).

Zhao, B. et al. High-resolution infrastructure defect detection dataset sourced by unmanned systems and validated with deep learning. Automation in Construction 163, 105405, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105405 (2024).

Flotzinger, J., Rösch, P. J., Oswald, N. & Braml, T. dacl1k: Real-world bridge damage dataset putting open-source data to the test. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 137, 109106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2024.109106 (2024).

Zha, Q., Yiming, Y., Zheng, Y., Ma, W. & Zhang, W. MBDD2025: A Deep Learning-Oriented Dataset for Diverse Building Defect Detection from UAV Images. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15622584 (2025).

Argentino, A. et al. Data normalization for the continuous monitoring of a steel truss bridge: A case study from the Italian railway line. Journal of Infrastructure Intelligence and Resilience 4, 100171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iintel.2025.100171 (2025).

Everingham, M. et al. The Pascal Visual Object Classes Challenge: A Retrospective. International Journal of Computer Vision 111, 98–136, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-014-0733-5 (2015).

Pan, B., Xiang, J., Zhang, N. & Pan, R. A fine-grained attributes recognition model for clothing based on improved the CSPDarknet and PAFPN network. Signal, Image and Video Processing 19, 230, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11760-025-03823-3 (2025).

Xie, J., Pang, Y., Nie, J., Cao, J. & Han, J. Latent Feature Pyramid Network for Object Detection. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 25, 2153–2163, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2022.3143707 (2023).

Liu, S., Qi, L., Qin, H., Shi, J. & Jia, J. Path Aggregation Network for Instance Segmentation (2018).

Hosang, J., Benenson, R. & Schiele, B. in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 6469–6477 (2017).

Baker, B., Gupta, O., Naik, N. & Raskar, R. Designing Neural Network Architectures using Reinforcement Learning. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1611.02167 (2017).

Pham, H., Guan, M. Y., Zoph, B., Le, Q. V. & Dean, J. Efficient Neural Architecture Search via Parameter Sharing (2018).

Howard, A. G. et al. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications (2017).

Long, X. et al. PP-YOLO: An Effective and Efficient Implementation of Object Detector (2020).

Huang, X. et al. PP-YOLOv2: A Practical Object Detector https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2104.10419 (2021).

Xu, S. et al. PP-YOLOE: An evolved version of YOLO. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2203.16250 (2022).

Ge, Z., Liu, S., Wang, F., Li, Z. & Sun, J. YOLOX: Exceeding YOLO Series in 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2107.08430 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research work is supported by Anhui Agricultural University High-level Introduction of Talents Start-up Program (Grant No. rc412402), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20240453), and the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (23KJB460032).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qikai Zha and Yiming Yao were primarily responsible for the overall planning of the dataset organization, image collection, annotation, and manuscript drafting. Yufan Zheng and Wanqi Ma contributed to manuscript revision and dataset maintenance. The final manuscript was reviewed by Wenkang Zhang.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zha, Q., Yao, Y., Zheng, Y. et al. A dataset of building surface defects collected by UAVs for machine learning-based detection. Sci Data 12, 2031 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06318-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06318-5