Abstract

Understanding the carbon cycle in Antarctic coastal systems is vital for evaluating the role of polar oceans in regulating atmospheric CO2 and global climate feedbacks. However, these areas remain poorly sampled and are underrepresented in existing carbon flux models. This dataset offers high-resolution environmental observations collected in February 2025 from surface waters and inland stations in Deception Island, an active volcanic caldera in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. It includes measurements of surface seawater pCO2, temperature, salinity, wind speed, air temperature, solar radiation, tidal elevation, and seismic signals (long-period and tremor events), along with related spatiotemporal metadata. To enhance direct observations, we applied a data-driven modeling approach using deep learning techniques. A Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) neural network was trained on multivariate sequences to estimate seawater pCO2, with model performance evaluated through five cross-validation folds. The final datasets contain both measured and Bi-LSTM-estimated pCO2 values. All data and processing steps adhere to FAIR principles to support research on air-sea gas exchange, remote sensing calibration, and Antarctic carbon system dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Since the Industrial Revolution, human activities such as large-scale deforestation, land-use and land-cover changes, cement production, and burning fossil fuels have significantly increased atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels. Over half of these human-caused CO2 emissions are offset by natural sinks that absorb CO2 on land and in oceans. According to the Global Carbon Budget (2024), the ocean alone absorbed about 26% of the total CO2 emissions during the decade from 2014 to 20231.

The Antarctic region plays a critical role in the global climate system and the carbon cycle. Its cold, nutrient-rich waters are essential areas for the absorption and storage of atmospheric CO2. The dynamics of its coastal zones, influenced by changes in sea ice, glacial melt, and complex ocean-atmosphere interactions, have significant effects on ocean biogeochemistry2,3. Additionally, the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica is one of the least sampled and fastest-changing marine environments on Earth4,5.

Beyond its role in the carbon cycle, the Southern Ocean is also the most significant heat sink in the world’s oceans. It absorbs approximately 60–90% of the excess heat stored in the global ocean since the mid-20th century, and around 83 ± 33% during the historical period of the climate models6. This remarkable capacity results from its unique circulation patterns, driven by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and strong westerly winds, which bring cold, deep waters to the surface. These waters efficiently transfer heat to the atmosphere before sinking into the ocean’s interior. By redistributing heat northward and ventilating the deep ocean, the Southern Ocean plays a key role in regulating Earth’s energy balance and mitigating the full impacts of surface warming7.

Better observational data from this region are vital for understanding local processes and their broader climate feedbacks, especially in the face of accelerating global change8,9.

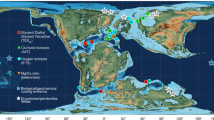

Deception Island, situated in the South Shetland Islands north of the Antarctic Peninsula (Fig. 1A), is located in the maritime Antarctic between the South American and Antarctic continents, making it one of the most climate-sensitive regions10. Its unique setting and dynamic environment have turned it into an exceptional natural laboratory for studying climate change, seismicity, geology, flora, and fauna, as well as for testing experimental instrumentation11,12,13,14,15. Over recent decades, these activities have helped build a comprehensive scientific database, thereby positioning the island among the most extensively studied areas in Antarctica, particularly in volcanology, seismology, and terrestrial biodiversity16.

(A) Location of Deception Island in the South Shetlands Archipelago, Antarctica, and (B) detail of the location of the AEMET meteorological station at the Gabriel de Castilla Spanish Base (GdC; yellow dot), the seismic stations (grey triangles), and the ship track along the day of the year 2025 (color bar) in Deception Island.

Geologically, Deception Island is the exposed rim of a submerged stratovolcano that ranks among the most active volcanoes in the region17. More than half of its surface (57%) is covered with ice, and various geological and geothermal processes co-occur, including hydrothermal activity, fumarolic emissions, ground deformation cycles and highly variable seismic activity18. Historical records document several eruptions over the past 200 years, with the most recent in 1970, which reshaped and expanded parts of the island19.

At the island’s center lies Port Foster (PF), a semi-enclosed bay formed by the flooding of a volcanic caldera (Fig. 1B). The basin covers about 38 km², has a perimeter of nearly 30 km, and connects to the Bransfield Strait via Neptune’s Bellows, a narrow, shallow channel averaging 22 meters in depth. The deepest parts of PF exceed 160 meters. Two permanent Antarctic research stations are located on the island: the Spanish Antarctic Base Gabriel de Castilla and the Argentine Antarctic Base Decepción.

Tides within PF are mixed, with predominantly semidiurnal components, and follow a mesotidal regime, characterized by ranges exceeding 2 m, due to the influence of astronomical forces. Average wind speeds are around 5 m s−¹, but gusts can reach 25 m s−¹, with both prevailing and extreme winds primarily coming from the southwest. Water circulation results from the combined effects of tides, weather variability, and thermal forcing, creating patterns similar to those seen in fjords, which is due to the contrast between the deep central basin and the shallow sill at Neptune’s Bellows20.

Several shallow coastal sites in PF, such as Pendulum Cove, Fumarole Bay, Whalers Bay, and Murature Beach, show intense geothermal activity. Fumaroles in these areas release gases from waters heated by convective flows from a subsurface magma chamber12. Emissions mainly consist of CO2 (75–90%) with smaller amounts of CH4, and interstitial water temperatures can reach nearly 100 °C. This geothermal activity creates strong, localized biogeochemical anomalies, including elevated levels of trace metals (Fe, Ni, Co and V) and increased greenhouse gas fluxes14.

This dataset compiles high-resolution measurements taken in February 2025 from PF. It combines surface seawater pCO2 levels with oceanographic variables (temperature, salinity), meteorological variables (wind speed, solar radiation, air temperature), and geophysical variables (seismic events, tidal elevation). Spatio-temporal metadata, such as geographic coordinates and date and time, are also included.

To complement direct observations, a modeling framework based on deep learning was applied to estimate seawater pCO2 using a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) neural network.

The resulting dataset combines direct observations and model-improved estimates of surface pCO2, offering a unique and robust resource for a wide range of scientific applications. It supports biogeochemical assessments, air-sea CO2 flux calculations, and regional climate analyses in polar coastal systems. Furthermore, the modelling approach, based on explainable deep learning, can serve as a valuable tool for improving the representation of CO2 dynamics in coupled ocean-atmosphere models, thereby contributing to more accurate climate projections. This dataset also enables the validation of satellite-based observations, the benchmarking of machine learning methodologies, and the extension of similar modeling frameworks to other data-scarce polar or volcanic marine environments.

Methods

Data acquisition

Environmental data were collected from February 11th to 18th, 2025, from coordinated marine and land sources to document high-resolution geophysical, chemical, and biological dynamics in the PF area of Deception Island (Fig. 1B).

Seawater was continuously sampled through a flow-through system onboard the Spanish R/V “Sarmiento de Gamboa”, with the ship track shown along the day of the year 2025 in Fig. 1B. Surface pCO2 concentrations in µatm (Fig. 2A) were measured using a ship-mounted CO2-Pro™ CV pCO2 Sensor (Pro-Oceanus Systems Inc.) that employed non-dispersive infrared detection. The sensor has an accuracy of ±0.5%.

Sea surface temperature, salinity, and solar radiation data were also collected onboard R/V “Sarmiento de Gamboa” by the Marine Technology Unit (UTM-CSIC). Seawater temperature and salinity (Fig. 2B,C) were measured with an SBE21 thermosalinograph sensor (Sea-Bird Scientific Inc.). The accuracy and precision are ±0.01 °C, ±0.001 S m−1, and ±0.01 °C and 0.0001 S m−1 for temperature and conductivity, respectively. Solar radiation in W m−2 (Fig. 2D) was recorded using the onboard multispectral radiometer PRR-800 sensor (Biospherical). All shipboard measurements were taken at a 1-second resolution, georeferenced, and synchronized via GPS.

Tidal elevation (Fig. 2E) was simulated using the Delft3D-FLOW model, with water level boundary conditions defined through astronomical forcing based on the main tidal constituents in the area.

Seismic data were collected using a network of broadband seismic stations located within the bay or the coast of the inner part of the island (Fig. 1B) from the Spanish National Geographic Institute (IGN) seismic catalog, which continuously monitors local volcanic activity with high sensitivity. In this study, we focused on two types of seismic signals: Long Period (LP) events and spasmodic tremors (TR). LP events are the dominant type of seismicity at Deception Island volcano. They present a feature characterized by emergent arrivals and a spindle-shaped envelope, with dominant frequencies below 5 Hz, and durations of only a few seconds18. Spasmodic tremors share certain traits with hybrid events, such as the presence of identifiable P- and occasionally S-wave arrivals, followed by a sustained low-frequency signal that contains energy at frequencies up to 8 Hz21. LP events and TR share indicating similarities in their source regions and processes22. Thus, TR and LP events are assumed to be different manifestations of the same source process21. These TR differ from isolated LP events in their longer duration and more complex spectral content, making them essential indicators of subsurface volcanic activity. Both signals were combined for inclusion in the model (Fig. 2H).

Air temperature and wind speed data (Fig. 2F,G) were collected from the meteorological station WMO-89070 operated by the Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (AEMET), Spain, at the Gabriel de Castilla Spanish Antarctic Base on Deception Island (GdC in Fig. 1B). Wind speed and direction were measured every 10 minutes at the 10 m above ground reference height.

All time series were quality-checked using instrument-specific thresholds and were post-processed to ensure consistency. The dataset includes a total of 30,404 data points, combining features and targets. The data were synchronized to UTC and uniformly resampled at a 1-minute interval.

Data Records

The full dataset is publicly available23 on the figshare repository (https://figshare.com/) and can be accessed via the following URL: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30112708.

Data were collected during the DICHOSO Project (https://doi.org/10.20351/29HE20240312), an interdisciplinary field campaign conducted in and around Deception Island (Antarctica) in February 2025. The dataset integrates georeferenced time-series measurements from oceanographic, meteorological, and geophysical sources, and is organized as a single CSV file in tabular format. A brief overview of the dataset structure and associated sub-datasets is provided in Table 1. Detailed descriptions of the variables included in the main file, including units, data types, and interpretation notes, are presented in Table 2.

The primary data file contains high-frequency (1-minute resolution) observations recorded during the vessel’s navigation through PF and from the inland seismic and meteorological stations. Each row corresponds to a unique timestamp and geographic position derived from the vessel’s GPS track. However, some variables, such as wind speed, air temperature, and seismic activity, originate from fixed stations on Deception Island. The geographic location of these stations is not included as a separate field in the dataset, but their measurements are temporally aligned and integrated into the unified data structure. Most variables were initially collected at 1-minute intervals; however, wind speed and air temperature were measured every 10 minutes and then replicated across each 1-minute time step within the corresponding 10-minute interval to ensure temporal consistency across all variables. The dataset includes measurements such as seawater temperature, salinity, surface pCO2, tidal elevation, solar radiation, air temperature, wind speed, and binary indicators of seismic activity. Additionally, a derived variable captures the number of seismic events within a 10-minute moving window, calculated as the sum of binary event occurrences (see Table 2 for details). Missing values are denoted by blank fields.

Additionally, seismic event metadata can be accessed through the Spanish Polar Data Center seismic catalog (https://doi.org/10.7419/162.03.2022; last accessed Nov 2025), and the SB21 sensor and meteorological raw data collected onboard the R/V Sarmiento de Gamboa and the meteorological data from the AEMET GdC station are archived in the CSIC Marine Technology Unit repository accessed through the Centro Nacional de datos Polares website (https://cndp.utm.csic.es/geonetwork/srv/eng/catalog.search#/home).

Technical Validation

To assess the potential of the dataset for predicting surface seawater pCO2 concentrations, we employed a deep learning approach using a Bi-LSTM architecture. This model was trained and validated with the complete set of multivariate features, including oceanographic data (such as seawater temperature, salinity, and tidal elevation), meteorological data (like wind speed, solar radiation, and air temperature), seismic events (including the number of LP and T), and location descriptors (latitude and longitude). Seismic signals were preprocessed to produce 10-minute rolling sums of event occurrence, enabling the model to incorporate information on previous subsurface activity. Although the data are arranged chronologically, this is not a typical time series task; instead, the model processes 3D windows of data (samples × time × variables), where time reflects sampling order but not continuous temporal flow.

To prevent data leakage and ensure a reliable evaluation, the dataset was divided using a 5-fold GroupKFold cross-validation strategy, with groups defined by scaled latitude values. This method ensures that geographically similar samples remain within the same fold and that model generalization is evaluated across different regions.

Input features (Fig. 2A–H) were normalized within each fold using StandardScaler, which applies z-score normalization. It transforms the data so that each feature has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Scalers were fitted exclusively on the training data and applied separately to both training and validation sets. This fold-specific normalization prevents any information from the validation set from leaking into the training process.

The Bi-LSTM model used is implemented in TensorFlow/Keras24 with two stacked Bidirectional LSTM layers featuring dropout regularization and L2 kernel regularization to prevent overfitting, followed by dense layers to produce the final pCO2 estimate. All input sequences were generated using a sliding window of 10 time steps, corresponding to 10 units of environmental data. A fixed random seed (42) was applied across all experiments to ensure reproducibility of data partitioning and weight initialization.

The model was trained with the RMSprop optimizer and early stopping based on validation loss. For each fold, we recorded the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and R² values between the observed and predicted pCO2, and saved the training and validation loss trajectories (Fig. 3A–C). The best fold yielded an RMSE of 8.655 and an R2 of 0.968 (Fig. 3B), and the resulting dataset is described in Table 3.

(A) Observed and predicted surface seawater pCO2 (μatm) across the training data sequence. (B) Relationship between observed and predicted surface seawater pCO2 (μatm) for the best-performing configuration. (C) Validation and training loss (mean squared error) for the best fold in the Bi-LSTM model, with the shaded area indicating the standard deviation among the five folds.

To further assess feature relevance, we calculated permutation importance across folds (Fig. 4). For each input variable, values were randomly permuted within the validation set (considering each time window and feature index), and the increase in RMSE was measured relative to baseline predictions. This process was repeated for each fold, and the average ± standard deviation across folds was reported for all features. The results highlighted the dominant influence of dial variability as represented by solar radiation and seawater temperature. Although seismic signals ranked lowest in global permutation importance, further analysis showed that their inclusion improved the model sensitivity to abrupt changes in pCO2 levels that could not be explained solely by environmental and physical variables. This analysis confirms the model ability to identify meaningful drivers of pCO2 variability in PF central area surface waters (Fig. 1B), supporting the robustness of the model interpretation.

All preprocessing steps, model training, and evaluation procedures were implemented in Python and are available in the accompanying code repository and supplementary files to support reproducibility and future benchmarking.

Usage Notes

Scripts and reproducibility

All scripts used to train, validate, and interpret the Bi-LSTM model are available in a public GitHub repository (https://github.com/susafle/CO2_prediction_BiLSTM). They are organized to facilitate reproducibility and adaptation to related datasets or modeling tasks. While detailed validation and methodology are provided in the Technical Validation section, the repository serves as a practical entry point for users wishing to replicate or expand upon this work.

Reuse potential

This dataset and modeling workflow have broad reuse potential in the fields of ocean biogeochemistry, climate modeling, and machine learning. The combination of physical, chemical, and seismic variables offers a valuable resource for studying the drivers of pCO2 variability in coastal and volcanic ocean regions. The structured time series format and model-ready input files enable other researchers to test different deep learning architectures (e.g., GRU, Transformer) or compare results with traditional statistical models (e.g., GAM, Cubist).

The dataset is particularly useful for benchmarking explainable AI techniques in environmental science because it includes permutation importance. Users can also modify the pipeline for other target variables (e.g., pH, carbonate saturation, dissolved inorganic carbon) or apply it to similar observational datasets from different regions. Including seismological signals provides a new opportunity to explore geophysical-biogeochemical interactions, particularly in tectonically or volcanically active coastal areas, such as Deception Island.

Researchers working on model interpretability, predictive performance evaluation, or transfer learning in environmental fields may find the modular structure of the scripts helpful, as it facilitates easier adaptation to new spatiotemporal settings or additional input features.

Limitations

The dataset concentrates on a specific region and time frame, which restricts the relevance of the findings to other oceanographic settings. Additionally, although several predictive variables were included, some potentially relevant parameters (e.g., dissolved oxygen, fluorescence) were not available and thus excluded from this version.

Ultimately, the significance of seismic variables may differ depending on the specific volcanic or tectonic setting, and caution should be taken when applying this approach to non-volcanic systems. Additionally, as with any data-driven model, the results rely on the quality of the data and the preprocessing decisions, which are clearly documented in the GitHub repository for transparency.

Data availability

The full dataset supporting this Data Descriptor is publicly available on the Figshare repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30112708. All data records described in this manuscript are accessible and downloadable from this DOI, which provides the complete meteocean and seismic dataset used for AI-based seawater CO2 estimations at Deception Island, Antarctica.

Code availability

All code files can be accessed via the GitHub repository https://github.com/susafle/CO2_prediction_BiLSTM.

References

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2024. Earth Syst Sci Data 17, 965–1039, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-17-965-2025 (2025).

Meredith, M. P. et al. Polar regions. In The Ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate: Summary for policymakers 1–3 (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2019).

Gruber, N. et al. The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 from 1994 to 2007. Science (1979) 363, 1193–1199, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau5153 (2019).

Fernández-Barba, M., Belyaev, O., Huertas, I. E. & Navarro, G. Marine heatwaves in a shifting Southern Ocean induce dynamical changes in primary production. Commun Earth Environ 5, 404, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01553-x (2024).

Abram, N. J. et al. Emerging evidence of abrupt changes in the Antarctic environment. Nature 644, 621–633, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09349-5 (2025).

Williams, R. G. et al. Asymmetries in the Southern Ocean contribution to global heat and carbon uptake. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 823–831, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02066-3 (2024).

Sallée, J.-B. Southern Ocean warming. Oceanography 31, 52–62, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2018.215 (2018).

Gregor, L. & Gruber, N. OceanSODA-ETHZ: a global gridded data set of the surface ocean carbonate system for seasonal to decadal studies of ocean acidification. Earth Syst Sci Data 13, 777–808, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-777-2021 (2021).

Newman, L. et al. Delivering Sustained, Coordinated, and Integrated Observations of the Southern Ocean for Global Impact. Front Mar Sci 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00433 (2019).

Luengo-S, O. et al. Long-term seawater temperature records at Livingston and Deception Islands, Antarctica. Frontiers in Marine Science 12, 1566852, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2025.1566852 (2025).

Yeguas, A. G., Almendros, J., Abella, R. & Ibáñez, J. M. Quantitative analysis of seismic wave propagation anomalies in azimuth and apparent slowness at Deception Island volcano (Antarctica) using seismic arrays. Geophys J Int 184, 801–815, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04864.x (2011).

Berrocoso, M. et al. Caldera unrest detected with seawater temperature anomalies at Deception Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Bull Volcanol 80, 41, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-018-1216-2 (2018).

Câmara, P. E. A. S. et al. Diversity and Ecology of Chlorophyta (Viridiplantae) Assemblages in Protected and Non-protected Sites in Deception Island (Antarctica, South Shetland Islands) Assessed Using an NGS Approach. Microb Ecol 81, 323–334, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-020-01584-9 (2021).

Belyaev, O. et al. Hydrothermal alteration of seawater biogeochemistry in Deception Island (South Shetland Islands, Antarctica). Front Mar Sci 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1432122 (2024).

Belyaev, O. et al. Assessing topographic features and population abundance in an Antarctic penguin colony through UAV-based deep-learning models. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 134, 104124, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2024.104124 (2024).

Tejedo, P., Gutiérrez, B., Pertierra, L. R. & Benayas, J. Analysis of published scientific research from Deception Island, South Shetland Islands. Antarct Sci 27, 134–149, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102014000455 (2015).

LeMasurier, W. E. et al. Volcanoes of the Antarctic Plate and Southern Ocean. Vol. 48, https://doi.org/10.1029/AR048 (American Geophysical Union, 1990).

Carmona, E., Almendros, J., Serrano, I., Stich, D. & Ibáñez, J. M. Results of seismic monitoring surveys of Deception Island volcano, Antarctica, from 1999–2011. Antarct Sci 24, 485–499, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102012000314 (2012).

Torrecillas, C., Berrocoso, M., Pérez-López, R. & Torrecillas, M. D. Determination of volumetric variations and coastal changes due to historical volcanic eruptions using historical maps and remote-sensing at Deception Island (West-Antarctica). Geomorphology 136, 6–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.06.017 (2012).

Flexas, M. M., Arias, M. R. & Ojeda, M. A. Hydrography and dynamics of Port Foster, Deception Island, Antarctica. Antarct Sci 29, 83–93, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102016000444 (2017).

Ibáñez, J. M. et al. The 1998–1999 seismic series at Deception Island volcano, Antarctica. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 128, 65–88, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-0273(03)00247-6 (2003).

Almendros, J., Ibáñez, J. M., Alguacil, G., Del Pezzo, E. & Ortiz, R. Array tracking of the volcanic tremor source at Deception Island, Antarctica. Geophys Res Lett 24, 3069–3072, https://doi.org/10.1029/97GL03096 (1997).

Flecha, S. et al. High-resolution meteocean and seismic dataset for AI modeling of seawater CO2 at Deception Island. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30112708 (2025).

TensorFlow Developers. TensorFlow (v2.5.0). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4758419 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the R/V Sarmiento de Gamboa and the Marine Technology Unit (UTM-CSIC) for their logistical support during the DICHOSO 2025 campaign. We also appreciate the entire scientific team of the DICHOSO project. Special thanks go to Juan Martínez and Antonio Moreno for their invaluable work in organizing campaign logistics, and to María Ferrer for her assistance in preparing and analyzing some of the samples. Funding for this work was supported by the DICHOSO project (PID2021-125783OB-100) and the VULCANA-III-IV project (IEO-2021–2026, IEO-CSIC). SF staff hired under the Generation D initiative, promoted by Red.es, an organization affiliated with the Ministry for Digital Transformation and the Civil Service, for attracting and retaining talent through grants and training contracts, financed by the Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan through the European Union’s Next Generation funds. This work contributes to the CSIC Interdisciplinary Thematic Platform, OCEANS + , and the Conexión PolarCSIC hub.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.H., A.T.-S., G.N. and S.F. conceived the study. E.H., A.T.-S., G.N., O.A.C.-M., M.D.-M., V.J.-M., G.C.-G., E.F., S.A.-B. and S.F. contributed to data collection. S.F., M.M., A.S., O.A.C.-M., M.D.-M., V.J.-M., and E.F. handled data processing. S.F. prepared the data for publication in a repository. S.F. wrote the first draft. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Flecha, S., Amaya-Vías, S., Medina, M. et al. Integrated meteocean and seismic dataset for AI-based seawater CO2 estimation at Deception Island, Antarctica. Sci Data 13, 38 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06351-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06351-4