Abstract

Soil Moisture (SM) has been monitored by satellite remote sensing for the past five decades. Among recent missions, the Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) mission, launched by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA), has been providing high-quality global SM observations from an L-band passive microwave radiometer with a revisit time of 1-2 days, although its spatial resolution remains on the order of tens of kilometers. To address this limitation, an algorithm was developed and applied to downscale the SMAP enhanced Level-2 radiometer half-orbit SM product from 9 km to 400 m resolution by incorporating land surface temperature (LST) and leaf area index (LAI) products from the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS). The 400 m downscaled SM product was validated against in situ observations acquired from the International Soil Moisture Network (ISMN) and compared with both 1 km downscaled and original 9 km SMAP products. Overall, the 400 m product outperformed the other two in terms of Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). It also revealed finer-scale spatial patterns of SM supporting local and regional hydrological applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Soil Moisture (SM), defined as the amount of water held in the soil, is a fundamental variable for characterizing land-atmosphere interactions, land surface processes, and the exchange of water and heat fluxes. It also serves as an essential input to land surface models that support a wide range of applications in hydrology, agriculture, ecology and meteorology1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Over the past several decades, satellite remote sensing has enabled global monitoring of SM through passive and active microwave instruments onboard Earth observation satellites. Compared to traditional point-scale ground-based measurements from field surveys, remotely sensed SM provides continuous, spatially distributed data with revisit intervals as short as 1–2 days. This not only improves representation of spatial heterogeneity in soils and land cover, and but also ensures more consistent data quality10,11,12,13,14,15. In particular, SM can be estimated from brightness temperature (TB) observations at passive microwave frequencies using retrieval algorithms7,16,17,18,19. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) mission provides global SM retrievals from L-band passive microwave radiometer TB observations, representing the top 0–5 cm depth layer, at a native spatial resolution of ~36 km with a revisit time of 1–2 days20,21. However, the spatial resolution of microwave radiometer-based SM retrievals is limited to tens of kilometers due to antenna size constraints. Although the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) SMAP enhanced the 36 km SMAP radiometer SM product to 9 km21, this resolution remains insufficient for many fine-scale hydrological studies and applications.

To address this limitation, numerous research has focused on downscaling passive microwave SM retrievals22,23. Depending on the datasets and mathematical approaches used, downscaling methods generally fall into three categories:

-

(1)

Integration of multi-sensor observations, combining optical/thermal with microwave radiometer or radar data7,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31.

-

(2)

Model-based approaches, which establish relationships between SM and other high-resolution land surface variables32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41.

-

(3)

Advanced mathematical or data assimilation techniques, including statistical methods and physics informed assimilation frameworks42,43,44,45,46,47,48.

In this study, we developed and implemented a SM downscaling algorithm based on apparent thermal inertia (ATI) principle, which falls under the category (1). The algorithm downscales the SMAP enhanced 9-km radiometer product to 400 m resolution using high resolution land surface temperature (LST) and leaf area index (LAI) data derived from the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS). The downscaled product covers the period 2015–2023 and was validated against in situ measurements from 31 SM monitoring networks provided by the International Soil Moisture Network (ISMN). For methodological details on the VIS/IR downscaling framework, readers are referred to the article26. Comparing to the original study, this article makes the following contributions:

-

(1)

We generated the first global remotely sensed SM product at 400 m resolution, derived from VIIRS-based downscaling, which improves the previously published 1 km downscaled SMAP SM product from the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC).

-

(2)

We introduced a new hybrid bias-correction approach that combines additive and ratio-based corrections, replacing the earlier additive-only method and thereby improving the robustness of the 400 m downscaled dataset.

-

(3)

We assessed the performance of the VIS/IR downscaling algorithm across multiple spatial scales, using global in situ SM data from the ISMN website, as well as discussed its implications for fine-scale hydrological applications.

Method

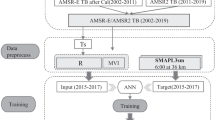

Downscaling algorithm

The 400 m downscaled SMAP SM data was generated using the visible/infrared (VIS/IR) algorithm26. This method is based on the thermal inertia relationship between SM and diurnal changes in LST, expressed as the SM-temperature difference (θ – ΔT). The implementation of the VIS/IR algorithm relies on several key assumptions: (1) There is an inverse relationship between SM and ΔT between the two VIIRS overpasses at 1:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m., which can be approximated as the maximum diurnal temperature difference6,49,50. (2) The θ – ΔT relationship can be parameterized using long-term outputs from the Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS) Noah model (1981–2020), including surface skin temperature and 0–10 cm SM content under dry-day conditions. A linear regression model was fit to establish this relationship. (3) Following the universal triangular relationship among Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), LST and SM51,52, regression fitting was conducted separately for different NDVI classes. To represent the spatial heterogeneity of vegetation and microwave penetration, the 5 km Long-Term Data Record (LTDR) NDVI data were used. In this study, the θ – ΔT pairs were grouped into 10 NDVI classes with an interval of 0.1 across the valid NDVI range of 0–1, and regression models were fit for each class. (4) Variability of the θ – ΔT relationship within a GLDAS grid (25 km) can be neglected. Thus, regression coefficients derived from GLDAS data were applied uniformly to all 400 m pixels within the grid. It should be noted that θ – ΔT correlation weakens under extreme weather events (e.g., heat waves, droughts and heavy precipitation), introducing uncertainty into the model.

Figure 1 illustrates θ-ΔT scatter plots and regression fits for three SM networks: REMEDHUS (40.33°N, 5.04 °W), SoilSCAPE (34.94 °N, 97.65 °W), and TxSON (30.31 °N, 98.78 °W), derived from GLDAS Noah outputs between 1981 and 2020 at 6:00 a.m. Across all networks, θ – ΔT shows a consistent inverse relationship. Regression lines across NDVI classes are generally parallel, though in cases with sparse data, some class specific lines cross others. The averaged R2 values across NDVI classes for REMEDHUS, SoilSCAPE, and TxSON are 0.41, 0.533, and 0.513, respectively.

The θ – ΔT regression model at the GLDAS grid scale (6:00 a.m. or 6:00 p.m.) is expressed as:

where \({a}_{0}\) and \({a}_{1}\) are regression coefficients for a given NDVI class, \({\theta }_{i,j}\) is the simulated SM estimate, and \({\triangle T}_{i,j}\) is the diurnal temperature difference at pixel (i, j). Thus, each GLDAS grid contains 10 sets of regression coefficients corresponding to NDVI classes.

A discrepancy exists between SM simulated from VIIRS data (via the GLDAS-based θ – ΔT relationship) and SMAP L-band retrievals, due to differences in sensing depth, (0–10 cm for GLDAS vs. 0–5 cm for SMAP) and sensing modality (optical vs. passive microwave). However, prior studies have shown that surface layer SM correlates strongly with shallow soil depths (~10 cm)53,54, making the datasets comparable after bias correction. The corrected 400 m estimate is defined as:

where \({\theta }_{i,{j}}^{{\prime} }\) is the corrected 400 m SM, \({\theta }_{i,j}\) is the model-simulated SM from Equation (1), and \(\Theta \) is the 9 km SMAP value. The correction was applied within a 36-km SMAP footprint by adjusting \({\theta }_{i,j}\) using both the additive difference and multiplicative ratio between \(\Theta \) and the mean of all n 400 m pixels in the footprint. The weighting parameter \(\alpha \) balances additive and ratio-based corrections:

where \({\sigma }_{\theta }\) is the local standard deviation within a 9 km grid, and k is a tuning constant (set to 0.02 following a previous study55. In areas of high variability, the correction relies more on the additive component, while in smoother regions it emphasizes the ratio-based adjustment. Compared with the original additive-only correction method26, the hybrid approach reduces blocky artifacts while preserving spatial patterns.

Validation metrics

To assess the accuracy of the original 9 km and the downscaled SMAP SM products, several statistical metrics were calculated: the coefficient of determination (R2), mean square error (RMSE), bias (\(b\)), unbiased RMSE (ubRMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and spatial standard deviation (SSD). They are defined as:

where \(\theta \) represents in situ SM measurement and \(\hat{\theta }\) is the SMAP SM estimate at resolutions of 400 m, 1 km or 9 km. The ubRMSE removes the effect of bias (\(b\)) from RMSE. MAE represents the mean absolute error, while SSD quantifies the spatial variability of SM across all stations within a given network. Each in situ measurement was compared with the closest SMAP grid cell at the corresponding resolution, ensuring the same number of point pairs across products of fair comparison.

Data

This study used multiple satellite and model datasets to implement the VIS/IR downscaling algorithm and to validate the downscaled and original SMAP SM products.

The SMAP satellite, launched by NASA in January 2015, operates in a near-polar, sun-synchronous orbit with local overpasses at 6:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m. The system carries an L-band microwave radiometer operating at multiple polarizations20,21,56,57. In this study, we used the enhanced Level 2 half-orbit 9 km product (SPL2SMP_E), derived from radiometer TB observations using the Single Channel Algorithm (SCA)2, and spatially enhanced via the Backus-Gilbert optimal interpolation method21. The 9 km SM product was downloaded from the NSIDC repository (https://nsidc.org/data/spl2smp_e/versions/6)58. For comparison, the 1 km downscaled SM product generated with the VIS/IR algorithm was obtained from the NSIDC repository (https://nsidc.org/data/nsidc-0779/versions/1)59.

The GLDAS system provides land surface variables generated by integrating satellite and ground observations with land surface modeling and data assimilation techniques to ensure consistency and quality60,61. We used GLDAS V2.0 (1981–1999) and V2.1 (2000–2020) outputs from the Noah land surface model (LSM) Level 4 model, specifically surface skin temperature and 0–10 cm SM content (https://ldas.gsfc.nasa.gov/gldas)62. The Noah model was originally developed by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP), as a land component for the Eta mesoscale model63,64.

The LTDR project provides global land surface climate records from 1981 to the present, using data of Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) onboard National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) N07 ~ N19 satellites and Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) onboard Aqua/Terra satellites. The LTDR products include daily surface reflectance, NDVI, LAI and Photosynthetically Active Radiation (FPAR) at 0.05° resolution65,66,67,68. We used AVHRR NDVI Version 5 data, downloaded from NASA’s LTDR website (https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/), to represent vegetation dynamics in the θ – ΔT downscaling framework.

The VIIRS instrument, onboard Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (NPP) and NOAA-20 satellites, provides global observations in 22 visible and infrared bands for variables including temperature, vegetation, snow/ice, and clouds. VIIRS offers improved spatial resolution and accuracy compared to AVHRR and MODIS69. In this study, we used two VIIRS products: (1) daily LST at 375 m, derived from I5 band (10.5–12.4 μm) using the VIIRS LST/emissivity algorithm with atmospheric correction, and (2) 8-day LAI at 500 m, retrieved with the MODIS LAI/FPAR operational algorithm70,71, from NASA’s website (https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/instruments/viirs). They both were resampled via nearest-neighbor interpolation method to 400 m resolution. LAI values were normalized to 0-1 to match NDVI class coefficients in Equation(1).

The Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission, launched in 2014 as a successor to Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM), provides precipitation and snow estimates globally72,73,74. The Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) Version 6 daily dataset, gridded at 0.1o resolution and covering 60oN - 60oS, was used to assess the effect of precipitation on SMAP retrievals from NASA’s website (https://gpm.nasa.gov/data)75.

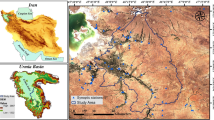

The ISMN is a global repository of long-term in situ SM measurements, hosting data from 80 networks and over 3000 stations since 195276,77,78,79,80. For this study, in situ of 0–5 cm SM measurements from 31 networks were obtained from the ISMN website (https://ismn.geo.tuwien.ac.at/). The networks span diverse continents, climates (humid to semi-arid) and land cover types (e.g., grassland, forest, agriculture, and shrubland). Their locations and details are presented in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1.

Data Records

The global 400 m downscaled SMAP soil moisture dataset is available through the University of Virginia’s data repository (https://doi.org/10.18130/V3/IVOU1T)81. The repository provides daily global SM data from April 1, 2015, to December 31, 2024. Files are named using the prefix “smap_sm_400m” followed by the corresponding year, and in Geographic Tagged Image File Format (GeoTIFF). Each file includes two layers corresponding to ascending and descending SMAP overpass SM observations and each layer is with raster dimensions of 36,540 rows × 86,760 columns. The SM raster layer is mapped in the Equal-Area Scalable Earth Grid 2.0 (EASE 2.0) projection, covering the global extent from 180° W to 180° E and 86° N to 86° S, with a grid spacing of 400.36 m.

Data Overview

Examples of the dataset are illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4. Figure 3 shows monthly mean 400 m downscaled SMAP SM on a global scale, while Fig. 4 presents weekly averages at three spatial resolutions (400 m, 1 km and 9 km) for three representative sub-basins: the Middle Colorado River basin, the Duero River basin and the San Joaquin River basin. Both inter-seasonal and inter-annual variability can be clearly captured. However, blocky artifacts are visible in the 400 m and 1 km SM maps, primarily due to (1) the coarse resolution of GLDAS inputs (25 km) used to construct the downscaling model, and (2) spatial heterogeneity in the θ – ΔT relationship.

Figure 5 illustrates the spatial patterns of SMAP SM data availability in percentage of valid daily observations, aggregated seasonally for the four climatological seasons: January-March (JFM), April-June (AMJ), July-September (JAS), and October-December (OND). Consistent spatial pattern can be observed across resolutions, with higher availability in arid and semi-arid regions (e.g., northern Africa, the Middle East, central Australia), where persistent clear-sky conditions lead to fewer retrieval gaps. In contrast, heavily vegetated and persistently cloudy regions, including the Amazon Basin, the Congo Basin, Southeast Asia, and parts of high-latitude boreal forests, exhibit lower availability due to frequent radio-frequency interference (RFI), dense vegetation canopy attenuation, and retrieval mask conditions. Seasonal contrasts are also evident: availability generally increases during the dry seasons and decreases during periods of enhanced cloudiness or vegetation growth. The strong agreement in spatial patterns across the 400 m, 1 km, and 9 km products demonstrates that the downscaling preserves the fundamental climatology of SMAP data availability while revealing finer-scale spatial heterogeneity at higher resolutions.

Technical Validation

Figures 6–7 and Tables 1–2 summarize validation results for the 400 m, 1 km, and 9 km SMAP SM products during the descending overpass (6:00 a.m.), evaluated against in situ SM observations. From Fig. 7 and Table 2, both ubRMSE (0.072 m3/m3) and MAE (0.066 m3/m3) for the 400 m product are lower than those for either the 1 km or 9 km SM data, demonstrating improved accuracy of the downscaled SM relative to the original SMAP retrievals. Scatter plots from Fig. 7a (TxSON) and Fig. 7c (SoilSCAPE) show that while 9 km point pairs are more concentrated, their regression fits are more biased compared with the 400 m and 1 km SM products. Consistently, the statistical metrics in Table 1 confirm that both downscaled products outperform the 9 km product. Only two networks (IMA_CAN1 and KIHS_SMC) exhibit higher ubRMSE at 400 m than at 9 km, while all others show improvements. Because the scale difference between 400 m and 1 km is smaller, the relative gains in ubRMSE and MAE are less pronounced than those between 400 m and 9 km.

A slight degradation in R2 is observed when moving from the original 9 km product (R2 = 0.426) to the downscaled versions (R2 = 0.409 at 1 km and R2 = 0.406 at 400 m). This reflects the classic bias-variance trade-off in downscaling. Increasing resolution introduces finer-scale variability, which raises variance and slightly lowers R². At the same time, the lower ubRMSE indicates a reduction in bias, meaning that although accuracy may fluctuate locally at the pixel level, the downscaled products provide a closer approximation to the true spatial distribution. This conclusion is further supported by SSD results in Fig. 8, which show that the downscaled values align more closely with the 1:1 diagonal compared to the 9 km data, particularly at TxSON (Fig. 7a) and SoilSCAPE (Fig. 7c). Across networks, only 5 sites (IMA_CAN1, NGARI, PBO_H2O, TAHMO, and TxSON) show a notable reduction in R2 at 400 m compared to 9 km, while most networks exhibit little or no degradation.

When comparing SSD values across datasets, the 400 m product (0.041 m3/m3) is the closest to the in situ benchmark (0.1 m3/m3), whereas the 1 km (0.039 m3/m3) and 9 km (0.033 m3/m3) products underestimate variability to a greater extent. This indicates that the 400 m downscaled SM better preserves spatial variability and captures finer-scale SM features, consistent with the scatter plots patterns shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 9 compares monthly averaged SMAP SM with accumulated GPM IMERG precipitation. All three SMAP products generally track in situ SM dynamics, though biases emerge during rainfall periods. For instance, the CR200_13 station in TxSON underestimates SM in early 2017 and late 2018, with reduced bias in both the 400 m and 1 km products. Such discrepancies likely reflect the impact of precipitation on SMAP retrieval quality, as rapid SM changes of SM following rainfall events are not always fully captured by the satellite estimates.

Usage Notes

In a summary, a VIS/IR downscaling algorithm, based on the vegetation-modulated thermal inertia relationship between SM and diurnal changes in LST, was developed to generate a global daily downscaled SMAP SM product at 400 m resolution. The downscaled SM datasets at 400 m and 1 km (obtained from the NSIDC repository) resolutions, together with the original 9 km product, were validated against in situ SM measurements from 31 monitoring networks worldwide, provided by the ISMN. Validation results show that the 400 m product achieved lower ubRMSE (0.025–0.365 m3/m3) and MAE (0.024–0.344 m3/m3) compared with both the 1 km and 9 km SM products. In addition, the average SSD of the 400 m dataset (0.041 m3/m3) was closer to the in situ benchmark (0.1 m3/m3) than either 1 km or 9 km data. These findings confirm that the 400 m downscaled SMAP SM product not only provides finer spatial detail but also improves overall accuracy relative to the native 9 km retrievals.

It should be noted that the global downscaled SMAP SM product is available only between approximately 65o N and 45o S, and contains missing data in some regions, mainly due to the limited availability of input datasets required for the downscaling algorithm.

Several limitations should also be considered when using this product. First, VIIRS data are derived from visible and infrared observations, which are unavailable in regions with persistent cloud cover. Second, SMAP retrievals have reduced accuracy under dense vegetation condition and pixels with vegetation water content greater than 5 kg/m2 should be excluded. Third, the algorithm relies on datasets from multiple sources with different sensing depths, introducing potential uncertainties and biases. Finally, there is an inherent spatial mismatch: remote sensing and LSM data are available at kilometer-scale resolutions, while in situ observations are point measurements.

Despite these limitations, the global 400 m downscaled SMAP SM product represents a significant advancement for remote sensing SM applications. Fine-scale SM data can better characterize the spatial patterns of small watersheds, supporting a wide range of regional and local applications, including precision agriculture, land-use planning, hydrology and water resources management, forestry, land management, and monitoring and assessment of hydrological extremes.

Data availability

The dataset is publicly available through the University of Virginia’s data repository at: https://doi.org/10.18130/V3/IVOU1T.

Code availability

The 400 m downscaled SMAP SM dataset was produced using open-source software packages Python and QGIS. The associated code files are publicly available at: https://doi.org/10.18130/V3/A9UJAV.

References

Dai, A., Trenberth, K. E. & Qian, T. A global dataset of Palmer Drought Severity Index for 1870–2002: Relationship with soil moisture and effects of surface warming. Journal of Hydrometeorology 5(6), 1117–1130 (2004).

Jackson, T. J. III. Measuring surface soil moisture using passive microwave remote sensing. Hydrological processes 7(2), 139–152 (1993).

Lakshmi, V., Wood, E. F. & Choudhury, B. J. A soil‐canopy‐atmosphere model for use in satellite microwave remote sensing. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 102(D6), 6911–6927 (1997).

Lakshmi, V. The role of satellite remote sensing in the prediction of ungauged basins. Hydrological processes 18(5), 1029–1034 (2004).

Lakshmi, V., Fayne, J. & Bolten, J. A comparative study of available water in the major river basins of the world. Journal of hydrology 567, 510–532 (2018).

Mallick, K., Bhattacharya, B. K. & Patel, N. K. Estimating volumetric surface moisture content for cropped soils using a soil wetness index based on surface temperature and NDVI. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 149(8), 1327–1342 (2009).

Njoku, E. G. & Entekhabi, D. Passive microwave remote sensing of soil moisture. Journal of hydrology 184(1-2), 101–129 (1996).

Robock, A. et al. The global soil moisture data bank. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 81(6), 1281–1300 (2000).

Wagner, W. et al. Operational readiness of microwave remote sensing of soil moisture for hydrologic applications. Hydrology Research 38(1), 1–20 (2007).

Bogena, H. R., Huisman, J. A., Oberdörster, C. & Vereecken, H. Evaluation of a low-cost soil water content sensor for wireless network applications. Journal of Hydrology 344(1-2), 32–42 (2007).

Brocca, L., Morbidelli, R., Melone, F. & Moramarco, T. Soil moisture spatial variability in experimental areas of central Italy. Journal of Hydrology 333(2-4), 356–373 (2007).

Cosh, M. H., Jackson, T. J., Bindlish, R. & Prueger, J. H. Watershed scale temporal and spatial stability of soil moisture and its role in validating satellite estimates. Remote sensing of Environment 92(4), 427–435 (2004).

Mohanty, B. P. & Skaggs, T. H. Spatio-temporal evolution and time-stable characteristics of soil moisture within remote sensing footprints with varying soil, slope, and vegetation. Advances in water resources 24(9-10), 1051–1067 (2001).

Robinson, D. A., Jones, S. B., Wraith, J. M., Or, D. & Friedman, S. P. A review of advances in dielectric and electrical conductivity measurement in soils using time domain reflectometry. Vadose Zone Journal 2(4), 444–475 (2003).

Zhao, T. et al. Soil moisture experiment in the Luan River supporting new satellite mission opportunities. Remote Sensing of Environment 240, 111680 (2020).

Lakshmi, V. Remote sensing of soil moisture. ISRN Soil Science, 2013 (2013).

Lakshmi, V. (Ed.). Remote Sensing of the terrestrial water cycle (Vol. 206). John Wiley & Sons (2014).

Schmugge, T., O’Neill, P. E., and Wang, J. R. (1986). Passive microwave soil moisture research. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, (1), 12-22.

Schmugge, T. & Jackson, T. J. Mapping surface soil moisture with microwave radiometers. Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics 54(1-4), 213–223 (1994).

Chan, S. K. et al. Assessment of the SMAP passive soil moisture product. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 54(8), 4994–5007 (2016).

Chan, S. K. et al. Development and assessment of the SMAP enhanced passive soil moisture product. Remote sensing of environment 204, 931–941 (2018).

Peng, J., Loew, A., Merlin, O. & Verhoest, N. E. A review of spatial downscaling of satellite remotely sensed soil moisture. Reviews of Geophysics 55(2), 341–366 (2017).

Sabaghy, S., Walker, J. P., Renzullo, L. J. & Jackson, T. J. Spatially enhanced passive microwave derived soil moisture: Capabilities and opportunities. Remote sensing of environment 209, 551–580 (2018).

Bolten, J. D., Lakshmi, V. & Njoku, E. G. Soil moisture retrieval using the passive/active L-and S-band radar/radiometer. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 41(12), 2792–2801 (2003).

Colliander, A. et al. Validation of SMAP surface soil moisture products with core validation sites. Remote sensing of environment 191, 215–231 (2017).

Fang, B. et al. Passive microwave soil moisture downscaling using vegetation index and skin surface temperature. Vadose Zone Journal, 12(3) (2013).

Fang, B., Lakshmi, V., Bindlish, R., Jackson, T. J. & Liu, P. W. Evaluation and Validation of a High Spatial Resolution Satellite Soil Moisture Product over the Continental United States. Journal of Hydrology 588, 125043 (2020).

Fang, B., Kansara, P., Dandridge, C. & Lakshmi, V. Drought monitoring using high spatial resolution soil moisture data over Australia in 2015–2019. Journal of Hydrology 594, 125960 (2021).

Narayan, U., Lakshmi, V. & Njoku, E. G. Retrieval of soil moisture from passive and active L/S band sensor (PALS) observations during the Soil Moisture Experiment in 2002 (SMEX02). Remote Sensing of Environment 92(4), 483–496 (2004).

Piles, M. et al. Downscaling SMOS-derived soil moisture using MODIS visible/infrared data. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 49(9), 3156–3166 (2011).

Piles, M. et al. A downscaling approach for SMOS land observations: Evaluation of high-resolution soil moisture maps over the Iberian Peninsula. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 7(9), 3845–3857 (2014).

Busch, F. A., Niemann, J. D. & Coleman, M. Evaluation of an empirical orthogonal function–based method to downscale soil moisture patterns based on topographical attributes. Hydrological Processes 26(18), 2696–2709 (2012).

Kim, S., Balakrishnan, K., Liu, Y., Johnson, F. & Sharma, A. Spatial disaggregation of coarse soil moisture data by using high-resolution remotely sensed vegetation products. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 14(9), 1604–1608 (2017).

Merlin, O. et al. Self-calibrated evaporation-based disaggregation of SMOS soil moisture: An evaluation study at 3 km and 100 m resolution in Catalunya, Spain. Remote sensing of environment 130, 25–38 (2013).

Mishra, V. et al. An initial assessment of a SMAP soil moisture disaggregation scheme using TIR surface evaporation data over the continental United States. International journal of applied earth observation and geoinformation 68, 92–104 (2018).

Pellenq, J. et al. A disaggregation scheme for soil moisture based on topography and soil depth. Journal of Hydrology 276(1-4), 112–127 (2003).

Peng, J., Niesel, J. & Loew, A. Evaluation of soil moisture downscaling using a simple thermal-based proxy–the REMEDHUS network (Spain) example. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 19(12), 4765–4782 (2015).

Ranney, K. J., Niemann, J. D., Lehman, B. M., Green, T. R. & Jones, A. S. A method to downscale soil moisture to fine resolutions using topographic, vegetation, and soil data. Advances in Water Resources 76, 81–96 (2015).

Tagesson, T. et al. Disaggregation of SMOS soil moisture over West Africa using the Temperature and Vegetation Dryness Index based on SEVIRI land surface parameters. Remote Sensing of Environment 206, 424–441 (2018).

Vergopolan, N. et al. SMAP-HydroBlocks, a 30-m satellite-based soil moisture dataset for the conterminous US. Scientific data 8(1), 264 (2021).

Werbylo, K. L. & Niemann, J. D. Evaluation of sampling techniques to characterize topographically-dependent variability for soil moisture downscaling. Journal of Hydrology 516, 304–316 (2014).

Bai, J., Cui, Q., Zhang, W. & Meng, L. An approach for downscaling SMAP soil moisture by combining sentinel-1 SAR and MODIS data. Remote Sensing 11(23), 2736 (2019).

Ko, A., Mascaro, G. & Vivoni, E. R. Irrigation impacts on scaling properties of soil moisture and the calibration of a multifractal downscaling model. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 54(6), 3128–3142 (2016).

Merlin, O., Chehbouni, A., Boulet, G. & Kerr, Y. Assimilation of disaggregated microwave soil moisture into a hydrologic model using coarse-scale meteorological data. Journal of Hydrometeorology 7(6), 1308–1322 (2006).

Reichle, R. H. et al. Comparison and assimilation of global soil moisture retrievals from the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer for the Earth Observing System (AMSR‐E) and the Scanning Multichannel Microwave Radiometer (SMMR). Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 112(D9) (2007).

Sahoo, A. K., De Lannoy, G. J., Reichle, R. H. & Houser, P. R. Assimilation and downscaling of satellite observed soil moisture over the Little River Experimental Watershed in Georgia, USA. Advances in Water Resources 52, 19–33 (2013).

Sánchez-Ruiz, S. et al. Combining SMOS with visible and near/shortwave/thermal infrared satellite data for high resolution soil moisture estimates. Journal of Hydrology 516, 273–283 (2014).

Zhao, W., Sánchez, N., Lu, H. & Li, A. A spatial downscaling approach for the SMAP passive surface soil moisture product using random forest regression. Journal of hydrology 563, 1009–1024 (2018).

Matsushima, D., Kimura, R. & Shinoda, M. Soil moisture estimation using thermal inertia: Potential and sensitivity to data conditions. Journal of Hydrometeorology 13(2), 638–648 (2012).

Minacapilli, M., Iovino, M. & Blanda, F. High resolution remote estimation of soil surface water content by a thermal inertia approach. Journal of Hydrology 379(3-4), 229–238 (2009).

Carlson, T. An overview of the “triangle method” for estimating surface evapotranspiration and soil moisture from satellite imagery. Sensors 7(8), 1612–1629 (2007).

Gillies, R. R., Kustas, W. P. & Humes, K. S. A verification of the ‘triangle’ method for obtaining surface soil water content and energy fluxes from remote measurements of the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and surface. International Journal of Remote Sensing 18(15), 3145–3166 (1997).

Mishra, V., Ellenburg, W. L., Markert, K. N. & Limaye, A. S. Performance evaluation of soil moisture profile estimation through entropy-based and exponential filter models. Hydrological Sciences Journal 65(6), 1036–1048 (2020).

Zha, X., Zhu, W., Han, Y. & Lv, A. Enhancing root-zone soil moisture estimation using Richards’ equation and dynamic surface soil moisture data. Agricultural Water Management 312, 109460 (2025).

Kisekka, I. et al. Spatial–temporal modeling of root zone soil moisture dynamics in a vineyard using machine learning and remote sensing. Irrigation science 40(4), 761–777 (2022).

McNairn, H. et al. The soil moisture active passive validation experiment 2012 (SMAPVEX12): Prelaunch calibration and validation of the SMAP soil moisture algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 53(5), 2784–2801 (2014).

Zhang, R., Kim, S., Sharma, A. & Lakshmi, V. Identifying relative strengths of SMAP, SMOS-IC, and ASCAT to capture temporal variability. Remote Sensing of Environment 252, 112126 (2021).

O’Neill, P. E. et al. SMAP Enhanced L2 Radiometer Half-Orbit 9 km EASE-Grid Soil Moisture. (SPL2SMP_E, Version 6). [Data Set]. Boulder, Colorado USA. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center. https://doi.org/10.5067/BN36FXOMMC4C. Date Accessed 10-08-2025 (2023).

Lakshmi, V. & Fang, B. SMAP-Derived 1-km Downscaled Surface Soil Moisture Product. (NSIDC-0779, Version 1). [Data Set]. Boulder, Colorado USA. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center. https://doi.org/10.5067/U8QZ2AXE5V7B. Date Accessed 10-08-2025 (2023).

Balsamo, G., Mahfouf, J. F., Bélair, S. & Deblonde, G. A land data assimilation system for soil moisture and temperature: An information content study. Journal of Hydrometeorology 8(6), 1225–1242 (2007).

Rodell, M. et al. The global land data assimilation system. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 85(3), 381–394 (2004).

Beaudoing, Hiroko and M. Rodell NASA/GSFC/HSL, GLDAS Noah Land Surface Model L4 3 hourly 0.25 x 0.25 degree, V2.1, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA, Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (GES DISC), https://doi.org/10.5067/E7TYRXPJKWOQ (2016).

Qi, W., Liu, J. & Chen, D. Evaluations and improvements of GLDAS2. 0 and GLDAS2. 1 forcing data’s applicability for basin scale hydrological simulations in the Tibetan Plateau. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 123(23), 13–128 (2018).

Qi, W. et al. Large Uncertainties in Runoff Estimations of GLDAS Versions 2.0 and 2.1 in China. Earth and Space Science 7(1), e2019EA000829 (2020).

Bédard, F., Crump, S. & Gaudreau, J. A comparison between Terra MODIS and NOAA AVHRR NDVI satellite image composites for the monitoring of natural grassland conditions in Alberta, Canada. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 32(1), 44–50 (2006).

Lakshmi, V., Czajkowski, K., Dubayah, R. & Susskind, J. Land surface air temperature mapping using TOVS and AVHRR. International Journal of Remote Sensing 22(4), 643–662 (2001).

Pedelty, J. et al. Generating a long-term land data record from the AVHRR and MODIS instruments. In Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 2007. IGARSS 2007. IEEE International (pp. 1021-1025). IEEE (2007, July).

Tian, F. et al. Evaluating temporal consistency of long-term global NDVI datasets for trend analysis. Remote Sensing of Environment 163, 326–340 (2015).

Cao, C., De Luccia, F. J., Xiong, X., Wolfe, R. & Weng, F. Early on-orbit performance of the visible infrared imaging radiometer suite onboard the Suomi National Polar-Orbiting Partnership (S-NPP) satellite. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 52(2), 1142–1156 (2013).

Islam, T. et al. A physics-based algorithm for the simultaneous retrieval of land surface temperature and emissivity from VIIRS thermal infrared data. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 55(1), 563–576 (2016).

Malakar, N. K. & Hulley, G. C. A water vapor scaling model for improved land surface temperature and emissivity separation of MODIS thermal infrared data. Remote Sensing of Environment 182, 252–264 (2016).

Hou, A. Y. et al. The global precipitation measurement mission. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 95(5), 701–722 (2014).

Huffman, G. J. et al. NASA global precipitation measurement (GPM) integrated multi-satellite retrievals for GPM (IMERG). Algorithm theoretical basis document, version, 4, 30 (2015).

Mao, Y., Crow, W. T. & Nijssen, B. A unified data‐driven method to derive hydrologic dynamics from global SMAP surface soil moisture and GPM precipitation data. Water Resources Research 56(2), e2019WR024949 (2020).

Huffman, G. et al. Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG), version 4.4. NASA’s Precipitation Processing Center, ftp://arthurhou.pps.eosdis.nasa.gov/gpmdata/ (2014).

Dorigo, W. A. et al. The International Soil Moisture Network: a data hosting facility for global in situ soil moisture measurements. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 15(5), 1675–1698 (2011).

Dorigo, W. A. et al. Global automated quality control of in situ soil moisture data from the International Soil Moisture Network. Vadose Zone Journal, 12(3) (2013).

Dorigo, W. et al. The International Soil Moisture Network: serving Earth system science for over a decade. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions, 1-83 (2021).

Gruber, A., Dorigo, W. A., Zwieback, S., Xaver, A., Wagner, W. (2013). Characterizing coarse-scale representativeness of in situ soil moisture measurements from the International Soil Moisture Network. Vadose Zone Journal, 12(2).

Schaefer, G. L., Cosh, M. H. & Jackson, T. J. The USDA natural resources conservation service soil climate analysis network (SCAN). Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 24(no. 12), 2073–2077 (2007).

Fang, B., SMAP 400m downscaled soil moisture daily data. https://doi.org/10.18130/V3/IVOU1T, University of Virginia Dataverse, V1 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely acknowledge the funding from the NASA Terrestrial Hydrology - NASA Award Number 80NSSC19K0993, Program Manager Dr. Jared Entin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bin Fang: Conceptualization, methodology, programming, visualization, validation, writing. Venkataraman Lakshmi: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, Review and editing, funding sponsor. Christopher Hain: Data collecting and processing, Review and editing, supervision. Vikalp Mishra: Data collecting and processing, Review and editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, B., Lakshmi, V., Hain, C. et al. A global 400-m high-resolution soil moisture dataset derived from multi-sensor remote sensing observations. Sci Data 13, 65 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06356-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06356-z