Abstract

Mountains in China are crucial for biodiversity conservation due to unique topography and climate, providing essential habitats and refugia for many plant species. Standardized open datasets along elevational gradients across multiple mountains remain limited. Here we used standardized field protocols to collect plant diversity data of 370 permanent sampling plots along elevations in 17 mountains. Species identity and abundance of all woody plants with ≥ 1 cm diameter at breast height were recorded. We calculated species-level basal area, abundance, and relative importance value for all plants, and separately for two vegetation layers. The dataset spans 46° longitude, 24° latitude, ranges from 166 to 3,835 m a.s.l., and includes 1,493 species from 121 families and 449 genera. It covers nearly all major ecosystems from tropical rainforests to tundra, providing baseline data for studying plant diversity changes along elevations and latitudes. This dataset enables direct comparisons across mountains, helping evaluate impacts of climate and land-use changes on species range shifts and ecosystem transitions, and inform conservation strategies for mountain ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Mountains cover about 25% of the world’s land surface, host more than 85% of the world’s amphibians, birds and mammals and play a crucial role in maintaining biodiversity as refuges, biodiversity hotspots and ecological corridors that support ecosystem function and stability1,2,3. Due to steep environmental gradients, diverse microhabitats, and complex topographical features, mountain plants exhibit high diversity, distinct distribution patterns, and specialized adaptations to varying climatic and soil conditions4,5. Meanwhile, as a result of geographical isolation and adaptive evolution, many mountain plants are highly endemic, resulting in a wealth of endemic species and unique vegetation types6. Documenting plant community composition across mountainous regions is essential for mapping species distributions and detecting spatial shifts in response to environmental changes. High-quality datasets on plant community-level monitoring could support the identification of biodiversity hotspots and inform conservation strategies under ongoing climate change.

Elevational gradients have long been recognized as natural laboratories for studying patterns of species composition, diversity, and ecosystem processes across environmental gradients7. Along these gradients, abiotic conditions such as temperature, precipitation, solar radiation, and soil nutrients change systematically and often steeply over short spatial scales. These environmental shifts lead to pronounced variations in species composition, functional traits, and community structure, offering valuable opportunities to disentangle the ecological and evolutionary drivers of biodiversity. Importantly, elevational gradients can be used to infer species climatic niches and potential distribution limits, making them especially relevant for assessing biological responses to global climate change. For instance, warming may lead to range shifts or increased extinction risks for high-elevation specialists8. These dynamics highlight the value of elevational studies in predicting distributional shifts and offering essential insights for biodiversity conservation in the Anthropocene.

Plant community data provide the basic information in species composition, community structure, and ecosystem functions9. By combining with environmental variables, plant evolutionary history and functional traits, these data help us understand biodiversity patterns, species interactions, the effects of environmental changes on vegetation dynamics, and evolutionary and ecological mechanisms10,11. Detailed plant community data, including species richness and abundance, are essential for revealing species interactions and other forces that determine species coexistence within and across plant communities12,13.

China harbors over 35,000 vascular plant species, with half of them being endemic14. Mountainous regions in China with varied climates and geological histories, covering over 50% of the land, host most of the country’s plant diversity15 and endangered species16,17. We initiated a long-term research network BEST (Biodiversity along Elevational gradients: Shifts and Transitions; https://BEST-mountains.org) in 2017, to monitor biodiversity dynamics of multiple taxa (e.g., vascular plants, mosses, soil microbes, soil fauna, insects and birds) under the changes of climate and land uses. This paper reports a comprehensive plant community dataset collected from 17 mountains along elevational gradients in China. Across 370 permanent sampling plots along 17 elevational transects, we used standard filed protocols18 to measure the diameter at breast height (DBH ≥ 1 cm) of each individual, tag one unique number and identify to species. For each plot, we calculated species-level basal area (BA), relative abundance (RA), relative dominance (RD), and relative importance value (RIV). These metrics were also calculated separately for the tree layer and the shrub and sapling layer. Following the rough DBH-based classification of vegetation layers commonly used in textbooks and published studies, individuals with DBH ≥ 5 cm were classified as the tree layer, representing mature trees, while trees and shrubs with DBH < 5 cm were classified as the shrub and sapling layer. These data provide a baseline for understanding how plant community composition and species diversity vary along elevational gradients in these mountains. Additionally, this dataset is valuable for global comparisons among mountain ecosystems, especially in the context of global changes in climate and land uses.

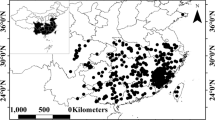

These 370 plots across 17 mountains span elevations from 166 m to 3,835 m (Fig. 1), and extend across 46° in longitude and 24° in latitude, encompassing diverse climatic zones, including temperate continental, temperate monsoon, subtropical monsoon, and tropical monsoon climates. Correspondingly, the vegetation types represented range from temperate coniferous forests, temperate coniferous broad-leaved mixed forests, and warm-temperate deciduous broadleaved forests, to subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests and tropical seasonal rainforests (Table 1). Totally, there are 1,493 woody plant species spanning 121 families and 449 genera (Fig. 2). The most species-rich families are Rosaceae, Lauraceae, and Fagaceae, contributing 123, 117, and 76 species (21% of total species), respectively. At the genus level, Rhododendron, Ilex, and Acer are the most diverse, comprising 49, 47, and 40 species (9% of total species), respectively. Among these, 995 species (67% of total species) occur only in a single mountain, and only 9 species are shared by half or more of the mountains. Plant diversity varies across mountain regions. The Bawangling on Hainan Island, south China, contains one of China’s largest tropical rain forests and supports the highest species richness, with 330 woody plants in the current dataset. Species richness in subtropical mountains ranges from 88 species in Daiyunshan to 261 species in Tianmushan. Qinling, situated in the subtropical-temperate transition zone and served as a natural boundary between south and north China, harbors 207 woody plants in our study sites. Temperate regions show relatively low richness, with West Tianshan in western China having only 23 species, and Changbaishan in northeastern China having 36 species. Overall, this dataset offers a baseline data for advancing biodiversity conservation of China’s forest flora.

Locations of the 17 studied mountains in China and representative plant species from each mountain: (a) Vatica mangachapoi from Bawangling; (b) Schima argentea from Damingshan; (c) Machilus chinensis from Chebaling (photo provided by Yongcai Zhao); (d) Fokienia hodginsii from Nanling; (e) Rhododendron sinogrande and (f) Euonymus frigidus from Gaoligong Mountains; (g) Pinus taiwanensis from Daiyunshan; (h) Rhododendron oreotrephes from Yulong Mountain; (i) Castanopsis eyrei from Guanshan (photo provided by Lin Chen); (j) Quercus engleriana from Jinfoshan; (k) Philadelphus sericanthus var. kulingensis from Lushan; (l) Daphniphyllum macropodum from Tianmushan; (m) Prunus obtusata from Dabieshan; (n) Abies chensiensis from Qinling (photo provided by Peiliang Liu); (o) Rhododendron concinnum from Baiyunshan; (p) Quercus variabilis from Lishan; (q) Pinus koraiensis from Changbaishan; (r) Malus sieversii from West Tianshan. The map of China is from: http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn.

The family-level phylogeny showing the evolutionary history of 1,473 plant species across 121 families. The inner circle shows the distribution of genus richness, and the outer circle shows species richness across families. Genus richness ranged from 1 to 27, and species richness ranged from 1 to 123. Both richness metrics were log10-transformed and then standardized to a range of 0 to 1 across the 121 families.

Methods

Field survey

A total of 370 permanent sampling plots were established during growing seasons from 2013 to 2025 along elevational gradients across 17 mountains, spanning elevations from 166 to 3,835 m a.s.l. and covering a total area of 31.95 ha (Table 1). The study sites range in longitude from 82°E to 128°E and in latitude from 19°N to 43°N (Fig. 1). According to the CHELSA dataset19, the 17 mountains show wide climatic variation, with annual mean temperature from −6.2 °C to 24 °C and precipitation from 351 to 2,925 mm (Table 1). For each mountain and elevation, typical vegetation types were selected. Plots of appropriate size were established along the gradient, with intervals of approximately 100 m in elevation. At each interval, one or two plots were established, depending on the complexity of the vegetation composition. Basic information such as latitude, longitude, and elevation was recorded for each plot. All woody plants with a diameter at breast height (DBH) ≥ 1 cm were tagged in the field, and their species names and DBH were recorded. For specimens that could not be confidently identified in the field, voucher specimens were collected and subsequently verified by local taxonomic experts. Scientific species names were standardized using World Flora Online20 and the Flora of China21, with the R package22,23. We used V.PhyloMaker224 with the GBOTB.extended.WP.tre backbone, which incorporates the megatrees of Smith & Brown25 and Zanne et al.26, to build a family-level phylogeny. A total of 121 families were represented in the mega-tree (Fig. 2). All these plots are scheduled to resurvey every five years. Currently, nine mountains (Bawangling, Chebaling, Gaoligong Mountains, Daiyunshan, Yulong Mountain, Guanshan, Tianmushan, Dabieshan, West Tianshan) have finished the first recensus of plant communities. Meanwhile, microclimatic variables, soil properties, and canopy cover have also been recorded. The microclimatic data have been partially shared through the SoilTemp network27, but are still incomplete for some recently established sites. Therefore, we did not include these data in the current release and will incorporate them in future updates.

To assess species dominance within woody plant communities, we calculated the importance value as a comprehensive measure of relative species significance. We used a standard filed protocol18 to record species identity, abundance, and diameter at breast height (DBH ≥ 1 cm) of all woody plants. Vegetation layers were classified as tree layer (DBH ≥ 5 cm) and shrub and sapling layer (DBH < 5 cm). We calculated species-level basal area (BA), abundance, relative abundance (RA), relative dominance (RD), and relative importance value (RIV) for each plot, as well as for tree layer and shrub and sapling layer separately. To calculate the RIV, only the main stems were considered, excluding root suckers and branches. The RIV for each species was calculated using the formula: RIV = (RA + RD) / 2, where Relative Dominance (RD) = (species’ basal area / total basal area of all species) × 100%; Relative Abundance (RA) = (number of individuals of the species / total number of individuals of all species) × 100%.

Data Records

The BEST plant community dataset described above is available at Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30877097)28. It includes four main data files in CSV format: a stand table summarizing stand-level variables for all BEST sites across 17 mountains (Table 2), a species list of all recorded plant species (Table 3), a community table containing detailed plant community composition data (Table 4), and an occurrence table documenting plant species occurrences across mountains (Table 5). Additionally, a family-level phylogenetic tree is provided in Newick format (“family_phylogeny.tre” on Figshare), which can be used for phylogeny-related studies.

Technical Validation

All plant surveys followed a standard field protocol to ensure consistency and comparability across these 17 mountains. Geographic coordinates of all 370 plots were precisely recorded using GPS devices. Overall, these rigorous technical validation steps ensure the dataset is robust, reliable, and valuable for a wide range of ecological and conservation research.

Usage Notes

These data enable the exploration of elevational patterns in plant species richness, community composition, and phylogenetic diversity across montane forest ecosystems in China. To ensure consistency across mountains, data cleaning was performed by excluding records related to branches and retaining only those associated with the main stem. Users should consider differences in sampling years among mountains when conducting temporal analyses. Additionally, some records could not be identified to the species level and remain unknown. Such records should be handled cautiously depending on the specific research question.

Data availability

The dataset supporting this Data Descriptor has been deposited in Figshare and is publicly available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30877097.

Code availability

No custom code was used to generate or process the data described in this study.

References

Rahbek, C. et al. Humboldt’s enigma: what causes global patterns of mountain biodiversity? Science 365, 1108–1113 (2019).

Perrigo, A., Hoorn, C. & Antonelli, A. Why mountains matter for biodiversity. Journal of Biogeography 47, 315–325 (2020).

Hoorn, C., Mosbrugger, V., Mulch, A. & Antonelli, A. Biodiversity from mountain building. Nature Geoscience 6, 154–154 (2013).

Körner, C. & Spehn, E. M. Mountain biodiversity: a Global Assessment. (Parthenon, Boca Raton, 2002).

Sundqvist, M. K., Sanders, N. J. & Wardle, D. A. Community and ecosystem responses to elevational gradients: processes, mechanisms, and insights for global change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 44, 261–280 (2013).

Muellner-Riehl, A. N. Mountains as evolutionary arenas: patterns, emerging approaches, paradigm shifts, and their implications for plant phylogeographic research in the Tibeto-Himalayan region. Frontiers in Plant Science 10 (2019).

Peters, M. K. et al. Predictors of elevational biodiversity gradients change from single taxa to the multi-taxa community level. Nature Communications 7, 13736 (2016).

La Sorte, F. A. & Jetz, W. Projected range contractions of montane biodiversity under global warming. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277, 3401–3410 (2010).

He, N. et al. Predicting ecosystem productivity based on plant community traits. Trends in Plant Science 28, 43–53 (2023).

Åkesson, A. et al. The importance of species interactions in eco-evolutionary community dynamics under climate change. Nature Communications 12, 4759 (2021).

Vellend, M. The Theory of Ecological Communities (Princeton University Press, 2016).

Ehrlén, J. & Morris, W. F. Predicting changes in the distribution and abundance of species under environmental change. Ecology Letters 18, 303–314 (2015).

Ohlmann, M. et al. Quantifying the overall effect of biotic interactions on species distributions along environmental gradients. Ecological Modelling 483, 110424 (2023).

Mi, X. et al. The global significance of biodiversity science in China: an overview. National Science Review 8, nwab032 (2021).

López-Pujol, J., Zhang, F.-M., Sun, H.-Q., Ying, T.-S. & Ge, S. Mountains of southern China as “Plant museums” and “Plant cradles”: evolutionary and conservation insights. Mountain Research and Development 31, 261–269 (2011).

Tang, Z., Wang, Z., Zheng, C. & Fang, J. Biodiversity in China’s mountains. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 4, 347–352 (2006).

Zhang, Z., He, J.-S., Li, J. & Tang, Z. Distribution and conservation of threatened plants in China. Biological Conservation 192, 454–460 (2015).

Condit, R. Tropical Forest Census Plots: Methods and Results from Barro Colorado Island, Panama and a Comparison with Other Plots (Springer, 1998).

Karger, D. N. et al. CHELSA-W5E5: daily 1 km meteorological forcing data for climate impact studies. Earth System Science Data 15, 2445–2464 (2023).

WFO (World Flora Online). An online flora of all known plants. http://www.worldfloraonline.org (2025).

Wu, Z., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Flora of China (Science Press, Beijing, 2005).

Zhang, J. & Qian, H. U. Taxonstand: an R package for standardizing scientific names of plants and animals. Plant Diversity 45, 1–5 (2023).

Zhang, J., Qian, H. & Wang, X. An online version and some updates of R package U.Taxonstand for standardizing scientific names in plant and animal species. Plant Diversity 47, 166–168 (2025).

Jin, Y. & Qian, H. V. PhyloMaker2: an updated and enlarged R package that can generate very large phylogenies for vascular plants. Plant Diversity 44, 335–339 (2022).

Smith, S. A. & Brown, J. W. Constructing a broadly inclusive seed plant phylogeny. American Journal of Botany 105, 302–314 (2018).

Zanne, A. E. et al. Three keys to the radiation of angiosperms into freezing environments. Nature 506, 89–92 (2014).

Lembrechts, J. J. et al. SoilTemp: a global database of near-surface temperature. Global Change Biology 26, 6616–6629 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Plant community data along elevational gradients in China’s 17 mountains, Figshare., https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30877097 (2025).

Ding, Y., Zang, R., Lu, X., Huang, J. & Xu, Y. The effect of environmental filtering on variation in functional diversity along a tropical elevational gradient. Journal of Vegetation Science 30, 973–983 (2019).

Huo, C., Zhang, Z., Hu, G. & Luo, Y. Altitude-related variation in carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus contents and their stoichiometry of woody organs in the subtropical mountain forests, south China. Ecology and Evolution 15, e71451 (2025).

Wang, R. et al. Inconsistent elevational patterns of soil microbial biomass, diversity, and community structure on four elevational transects from subtropical forests. Applied Soil Ecology 201, 105462 (2024).

Shen, Y. et al. Mixed-species bird flocks re-assemble interspecific associations across an elevational gradient. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 289, 20221840 (2022).

Song, J. et al. Leaf and root traits show contrasting resource exploitation strategies, but converge along elevation in the Hengduan Mountain forests. Journal of Biogeography 52, e15157 (2025).

Chen, B. et al. What control home‐field advantage of foliar litter decomposition along an elevational gradient in subtropical forests? Plant and Soil, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-024-07165-w (2025).

Luo, Y.-H. et al. Greater than the sum of the parts: how the species composition in different forest strata influence ecosystem function. Ecology Letters 22, 1449–1461 (2019).

Ma, L. et al. When microclimates meet soil microbes: temperature controls soil microbial diversity along an elevational gradient in subtropical forests. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 166, 108566 (2022).

Qian, S. et al. Conservation and development in conflict: regeneration of wild Davidia involucrata (Nyssaceae) communities weakened by bamboo management in south-central China. Oryx 52, 442–451 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Spatial distribution pattern and correlation of dominant species in the arbor layer at a 25 hm2 forest plot in Lushan Mountain, China. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 34, 1491–1499 (2023).

Zhang, R. et al. A taxonomic and phylogenetic perspective on plant community assembly along an elevational gradient in subtropical forests. Journal of Plant Ecology 14, 702–716 (2021).

Wu, D. et al. Tree height and not climate influences intraspecific variations in wood parenchyma fractions of angiosperm species in a mountain forest of eastern China. American Journal of Botany 112, e70035 (2025).

Jia, S. et al. Neighbouring tree effects on leaf herbivory: insect specialisation matters more than host plant leaf traits. Journal of Ecology 112, 189–199 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Distinct strategies of soil bacterial generalists and specialists in temperate deciduous broad-leaved forests. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 91, e00992–25 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Tree mycorrhizal associations strongly mediate soil microbial β-diversity along an elevational gradient in a warm-temperate forest. Applied Soil Ecology 205, 105776 (2025).

Fang, S. et al. Disturbance history, neighborhood crowding and soil conditions jointly shape tree growth in temperate forests. Oecologia 205, 295–306 (2024).

Tian, Z. et al. Wild apples are not that wild: conservation status and potential threats of Malus sieversii in the mountains of Central Asia biodiversity hotspot. Diversity 14, 489 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the field crews in 17 mountains to collect the data, including Kankan Shang, Lin Chen, Qingni Song, Mingshui Zhao, Xin Wang, Yuzhuo Wang, Ran Zhang, Jiaxin Kong, Xianyu Yang, Oukai Zhang, Xuan Lv, Jiale Chen, Yaoshun Lu, Hongwei Zhang, Luwen Ma, Li Shu, Pengcheng Liu, Fang Wang, Xiaofan Shang, Jingchao Zhao, Junhong Chen, Mufan Sun, Min Guan, Pu Zheng, Yuetong Wang, Li Huang and Xijin Zhang. This work is part of the BEST (Biodiversity along Elevational Gradients: Shifts and Transitions; https://BEST-mountains.org) research network. This work was supported by the Fund of CAS Key Laboratory of Forest Ecology and Silviculture, Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (KLFES-2036, KLFES-2027), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31500355, 31670630, 32071652, 32101280, 32230067, 32271616, 32301401, 32401334, 32471623, 32471852, and 41671047), the Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2023ZKZD36), the Jiangxi Natural Science Foundation (20242BAB25345, to Zhaochen Zhang), the Special Funding for Guangxi Bagui Young Top Scholar (to Zhonghua Zhang), the Excellent Young Scientist Program of Liaoning province (2024JH3/10200024), and the Doctoral Start-up Foundation of Liaoning Province (2024010292-JH3/101).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. conceived the idea for the project and compiled the data. All authors were involved in collecting datasets. The first draft, the figures and tables were produced by X.W. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript and contributed to the revised versions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Chen, Y., Chen, Y. et al. Plant community data along elevational gradients in China’s 17 mountains. Sci Data 13, 100 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06414-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06414-6