Abstract

Podocyte (POD) injury is a hallmark of glomerular diseases and a central cause of albuminuria and nephrotic syndrome. Despite the rapid advancements in single-cell sequencing technologies in recent years, POD capture remains limited, resulting in a lack of comprehensive single-cell datasets related to Podocytopathies (PCPs). In this study, we collected kidney tissues from patients with five types of PCP and established two mouse models of POD injury for single-nucleus RNA sequencing (sn-RNA seq). We successfully generated single-cell resolution kidney atlases of human and mouse PCPs and, in combination with microalbuminuria-associated genome wide association study (GWAS) dataset, identified potential therapeutic targets linked to POD injury. These findings provide valuable resources and a solid foundation for future research on PCPs, particularly on the molecular mechanisms underlying POD injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Podocytes (PODs) are among the most critical parenchymal cells in the kidney, working alongside glomerular endothelial cells (GECs) and the glomerular basement membrane to form the glomerular filtration barrier1. They play an essential role in filtering plasma proteins and regulating glomerular filtration pressure and function2. When affected by immune, metabolic, genetic, or pharmacological factors, PODs may become damaged3,4,5. Due to their terminal differentiation, repair through cellular proliferation is limited, and while compensatory hypertrophy and potential regenerative pathways can temporarily stabilize the filtration barrier, sustained damage leads to progressive POD loss and ultimately glomerulosclerosis6,7.

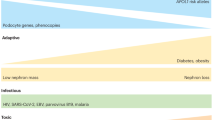

POD injury is present in nearly all glomerulonephritis cases, with certain diseases, such as immune-mediated minimal change disease (MCD), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and membranous nephropathy (MN), as well as those secondary to metabolic disorders like diabetic nephropathy (DN) and obesity-related nephropathy (OBN), having POD injury as the core pathological feature8,9. These conditions present clinically with albuminuria, edema, and hypertension, constituting the major types of nephrotic syndrome. However, due to limited insights into the mechanisms of POD injury, treatments still largely rely on corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapies10.

With the rapid advancement of single-cell sequencing technologies, the exploration of kidney cell injury mechanisms has accelerated, leading to the establishment of extensive single-cell sequencing resource repositories, such as kidney precision medicine project11. However, most of these projects focus on kidney tissues from patients with DN, hypertensive nephropathy, lacking representation of PCPs. Furthermore, the loss of PODs results in reduced capture rates, and there is currently no dedicated single-cell dataset for PCPs, hindering deeper exploration into the pathogenesis of these conditions.

In this study, we collected renal biopsy tissues from five different PCP cohorts (MCD, FSGS, DN, MN, OBN) and constructed two mouse models of POD injury for single-nucleus RNA sequencing (sn-RNA seq). We identified over 20 renal cell types, including PODs, and integrated the data with genome wide association study (GWAS) findings on microalbuminuria (MA) to further identify key genes associated with POD injury and the development of PCPs. These findings provide a rich single-cell data resource and potential therapeutic targets for the study of PCPs.

Methods

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Approval Number: 2024-0529). All participants provided written informed consent, including consent for publication. Animal experiments were conducted in compliance with the ethical guidelines set forth by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Zhejiang University (Approval Number: SRRSH2024-0003).

Patients

We collected renal tissue samples from patients diagnosed with MCD, focal FSGS, DN, MN, and OBN, with three patients in each group, at the Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, between 2021 and 2025. The pathological diagnoses were evaluated by experienced renal pathologists to ensure accuracy and diagnostic specificity, and were subsequently confirmed by clinical nephrologists based on clinical manifestations and laboratory findings in accordance with the KDIGO guidelines12. Notably, all FSGS patients included in this study were screened to exclude hereditary causes. None of the participants had major comorbidities such as cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases.

Electron microscopy demonstrated marked POD injury in all patients, characterized by extensive foot process effacement and loss. Importantly, none of the patients had received corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy prior to renal biopsy, and all exhibited preserved renal function with a estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) greater than 90 mL/min/1.73 m². Representative H&E-stained images of glomeruli from these patients are shown in Fig. 1.

Additionally, we obtained kidney tissues from three patients undergoing unilateral nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma as healthy control samples. These control patients also provided written informed consent, and their clinical details are summarized in Table 1.

In accordance with ethical guidelines, no personally identifiable information (PII) is included in the sequencing data. All data were anonymized prior to analysis, and any potential identifiers were removed. We have ensured that participant confidentiality was rigorously maintained throughout the study.

Animal models

All mice used in this study were male. To establish two POD injury mouse models, we purchased 8-week-old Balb/c mice and C57BL/6 J mice from Cygen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. For the adriamycin-induced POD injury model (ADRN), Balb/c mice were administered a single tail vein injection of adriamycin at a dose of 9 mg/kg. Mice were euthanized 6 weeks after the injection for tissue collection. The obesity-mediated POD injury model was established by feeding C57BL/6 J mice a high-fat diet (Research Diets D12492, 60% kcal from fat) for 16 weeks. Control groups for both models consisted of the respective corresponding mouse strains, which were either injected with physiological saline or fed a normal diet.

Following the establishment of the models, blood, urine, and kidney tissue were collected to assess the development of POD injury. Upon evaluation, both ADRN and OBN mice exhibited significantly increased urinary albumin creatinine ratio compared (UACR) with controls. Moreover, ADRN mice showed marked glomerulosclerosis, whereas OBN mice displayed pronounced glomerular hypertrophy (Fig. 2).

Establishment of mouse models. (A) Bar graph showing UACR in ADRN and control mice. (B) Representative H&E stained images of glomeruli from ADRN and control mice. (C) Bar graph showing UACR in OBN and control mice. (D) Representative H&E–stained images of glomeruli from OBN and control mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5). Statistical comparisons were performed using the t-test; ***P < 0.001. Scale bar, 100 µm.

Finally, three mice from each group were randomly selected, and their kidney tissues were used for sn-RNA seq.

Single-nucleus suspension preparation and single-cell nucleus sequencing

Both human renal biopsy specimens and mouse renal cortical tissues were promptly snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen following collection and subsequently stored at –80 °C for later analyses. Renal tissues from both human and mouse samples were processed into single-cell suspensions using the Shbio Nucleus Isolation Kit (Shbio, 52009-10). The resulting suspensions were then combined with barcode gel magnetic beads and oil, and loaded into different chambers of the Chromium Chip K. Gel beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) were formed using the 10X Genomics Chromium system. Subsequently, the GEMs were transferred to a PCR machine for reverse transcription, followed by magnetic bead-based purification of single-stranded cDNA.

The purified cDNA was then amplified using PCR. The cDNA concentration was quantified using Qubit, and fragment size was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Upon confirming the quality of the cDNA, library construction was performed. Finally, the libraries were subjected to cluster generation and hybridization with the first-strand sequencing primers, as per the Illumina User Guide. The flow cell, containing the clusters, was loaded onto the sequencer, and paired-end sequencing was performed. The sequencing process was monitored and controlled using the Illumina Data Collection Software.

Gene expression quantification

Raw FASTQ files obtained from sn-RNA seq of human and mouse kidney tissues were processed using the Cell Ranger (8.0.0) pipeline, based on the GRCh38 human reference genome and the GRCm38 mouse reference genome. Quality control was performed to filter out low-quality cells, as well as to remove environmental contaminants and chimeric reads. Following quality control, gene expression quantification was carried out by counting the unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) corresponding to each gene. This workflow was strictly adhered to the official 10X Genomics guidelines to ensure accuracy and consistency in data processing.

Data analysis and visualization

Data processing and analysis for both human and mouse samples followed the same standards and workflow. Specifically, we performed stringent quality control on the snRNA-seq data derived from different samples. First, we applied DecontX package (version 1.4.0) to corrected counts arising from ambient RNA molecules and random barcode swapping in the snRNA-seq data13. In addition, nuclei with UMI counts greater than 5,000 or fewer than 200, as well as those in which more than 5% of reads were derived from mitochondrial genes, were filtered out. Furthermore, we employed DoubletFinder package (version 2.0.4) to identify and remove potential doublets. Following quality control, we employed scVI package (Version 1.3.1) to integrate the data and remove batch effects14. After determining the optimal dimensionality reduction parameters using the GetPC function from the SCNT package (Version 1.1.0)15, we performed cell clustering using the Leiden algorithm. Clusters were defined and named based on cell-type markers identified in previous studies.

Subsequently, we visualized the cell clusters using UMAP or t-SNE, depending on the cell distribution. Differential gene expression analysis was conducted using the FindMarkers function from the Seurat package (version 5.1.0), considering genes expressed in at least 25% of the cells. Genes with a corrected p-value (FDR) < 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change (log2FC) ≥ 0.25 were deemed significant. The Startrac package (0.1.0) was used to calculate the ratio of observed over expected cell numbers (Ro/e index)16. The enrichment analysis was performed using clusterProfiler package (version 4.10.1).

Additionally, we obtained summary-level data from the CKDGen Consortium for MA-associated GWAS, including European-American and African-American populations17. We used MAGMA package (Version 1.08)18 to convert the GWAS data into an appropriate format and performed joint single-cell and GWAS analysis using SeismicGWAS package (Version 1.0.0)19. This method is based on calculating gene specificity scores and incorporating influential gene analysis to identify key genes that drive each cell type–trait association, thereby constructing a comprehensive map linking polygenic traits to cell type–specific gene expression. Gene risk and specificity scores were calculated to assess the genetic association between POD gene expression and MA.

For visualization, violin plots were generated using the MySeuratWrappers package (Version 0.1.0), heatmaps using the pheatmap package (Version 1.0.12), feature plots using the SCP package (0.5.6), Venn diagram using the VennDiagram package (Version 1.7.3) and bubble plots using the SCNT package. UMAP, t-SNE, and bar plots for changes in cell proportions were created with the scRNAtoolVis package (Version 0.0.7). All analyses were performed in R (version 4.3.0), except for scVI and GWAS data format conversion, which were conducted in Python 3.9.

Data Records

All sn-RNA seq datasets generated in this study, including both raw and processed RDS data for PCPs, have been uploaded and made publicly available. The dataset is organized into human and mouse subfolders. The raw paired-end FASTQ files are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession numbers SRP637787 (human, 18 samples)20 and SRP639901 (mouse, 12 samples)21. The processed RDS files (PODh.RDS for human and PODm.RDS for mouse), the marker genes used for cell-type annotation, the cell numbers for each cell type in the human and mouse snRNA-seq datasets, the genetic associations between POD-specific gene expression and MA, and the differentially expressed genes between healthy and injured PODs in both species are all provided as tables and are publicly available in the Zenodo repository (https://zenodo.org/records/17614667)22.

File names follow a consistent convention including sample name and unique identifier, and sample labels are identical between the raw and processed datasets. Each RDS file contains gene expression matrices, metadata (cell type, condition, and sequencing information), and gene annotations.

Technical Validation

The overall data processing and validation workflow is illustrated in Fig. 3. To ensure the validity and quality of the dataset, all human and mouse samples underwent strict quality control procedures at both the experimental and computational stages. During library preparation, the cDNA fragment size distribution of each sample was evaluated using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. All samples showed a clear single peak with an average fragment length of approximately 1,400 bp, indicating well-preserved RNA integrity and high-quality libraries suitable for sequencing (Table 2).

The workflow of this study, which is created in https://BioRender.com.

Raw sequencing reads were examined using FastQC to assess base quality scores, GC content, sequence duplication levels, and adapter contamination. All samples met the quality requirements for sn-RNA seq, with Q30 scores above 90%. And in order to generate high-quality downstream RDS datasets, we applied stringent filtering criteria during data preprocessing: 1) Genes expressed in fewer than three cells were removed. 2) Cells with fewer than 200 or more than 5,000 detected genes were excluded. 3) Cells with > 5% mitochondrial gene expression were filtered out.These criteria effectively removed low-quality or dying cells, ensuring reliable biological signal retention.

After rigorous quality control and data integration, we obtained 160,511 high-quality nuclei from kidney tissues of 15 PCP patients and 3 controls. Based on previously reported kidney cell markers11, we classified the nuclei into 22 distinct cell types, covering the majority of kidney regions and tissues. These included four endothelial cell types: afferent/efferent arteriole (AEA) cells, peritubular capillary cells (PTCs), GECs, and lymphatic (LYM) cells. Additionally, we identified four types of collecting duct cells: connecting tubule (CNT) cells, principal cells (PCs), intercalated cells (ICA and ICB), inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) cells, as well as six other epithelial cell types, including PODs, parietal epithelial cells (PECs), proximal tubule (PT) cells, injured PT (PT-inj) cells, thin limb (TL) cells thick ascending limb (TAL) cells and macula densa (MD) cells. Furthermore, we also identified stroma cells such as fibroblasts (FIBs) and vascular smooth muscle cells/pericytes (VSM/Ps), along with immune cells including Macrophages (MACs), T cells, and plasma (PL) cells (Fig. 4A,B).

Processing of sn-RNA seq data from PCP patients and identification of POD subgroups. (A) Violin plot showing the markers of 22 human kidney cell types. (B) UMAP visualization of the 22 cell types identified in PCP patients. (C) Heatmap depicting the Ro/e indices of the 22 cell types in DN, FSGS, MCD, MN, OBN patients and controls. (D) T-SNE plot showing the two POD subgroups (hPOD and iPOD). (E) Bar chart displaying the changes in POD subgroup proportions between PCP patients and controls. (F) Bubble plot of KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for genes significantly upregulated in iPODs compared with hPODs.

In a total of 18 human kidney tissue samples, we identified 2,068 PODs. Notably, the Ro/e index of PODs in all PCPs, except for MN, was significantly reduced compared to the control group (Fig. 4C). We then performed re-clustering on the 2,068 PODs and identified two distinct subgroups. Interestingly, PODs markers previously reported in the literature, including WT1, NPHS1/2, and SYNPO23, were markedly downregulated in one of these subgroups. Based on this, we classified the two subgroups as healthy PODs (hPODs) and injured PODs (iPODs) (Fig. 4D,E). Enrichment analysis indicated that genes significantly upregulated in iPODs compared with hPODs are markedly enriched in metabolic pathways such as ascorbate and aldarate metabolism and glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism. These findings indicate that PODs undergo pronounced metabolic reprogramming during the injury process, suggesting enhanced oxidative stress response and altered amino acid metabolism (Fig. 4F).

Similarly, we integrated snRNA-seq data from three ADRN mice and three OBN mice, along with their corresponding controls, totaling 12 samples. After quality control, we retained 115,159 high-quality cells. Based on known markers24, these cells were classified into 17 distinct cell types, including PODs, endothelial cells (ECs), tubular cells, and immune cells (Fig. 5A,B). Notably, the Ro/e index of PODs in both ADRN and OBN mice was significantly lower than that of the control group (Fig. 5C).

Processing of sn-RNA seq data from POD injury mouse models and identification of mouse POD subgroups. (A) Feature plot showing marker genes for 16 mouse kidney cell types. (B) UMAP visualization of the 16 cell types in mouse samples. (C) Heatmap displaying the Ro/e indices of different cell types in ADRN, OBN, and control mice. (D) T-SNE plot showing the two POD subgroups (hPOD and iPOD) in mice. (E) Bar chart illustrating the changes in POD subgroup proportions between ADRN, OBN, and control mice.

Following the same analytical strategy, we extracted 818 PODs from the mouse dataset and further subdivided them into hPOD and iPOD populations (Fig. 5D). Compared to controls, hPODs were markedly reduced in both ADRN and OBN mice, while iPODs were increased (Fig. 5E).

Subsequently, by integrating human snRNA-seq data with multi-ancestry MA GWAS results, we identified 92 genes in PODs that are potentially genetically associated with MA (Fig. 6A). We then conducted differential gene expression analysis for hPODs and iPODs in both human and mouse datasets. In human hPODs, 3,677 genes were significantly upregulated, while 8,419 were significantly downregulated (Fig. 6B). In the mouse hPODs compared to iPODs, 3,813 genes were upregulated and 7,837 downregulated (Fig. 6C).

Joint analysis of sn-RNA seq and GWAS data reveals POD-specific genes genetically associated with MA. (A) Scatter plot showing genes identified in PODs that are associated with MA, with the x-axis representing gene risk and the y-axis representing gene specificity. Red points indicate genes with a significant association to MA, while gray points represent non-significant genes. (B) and (C) Differentially expressed genes between hPOD and iPOD in humans and mice, respectively. Genes with FDR < 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 0.25 are considered significant. (D) Venn diagram showing the overlap of common differentially expressed genes between humans and mice, and the intersection with MA-associated genes. (E) Bubble plot displaying the expression of 16 key genes in hPOD and iPOD from both humans and mice.

By intersecting the differentially expressed genes with those that showed potential genetic association, we ultimately identified 16 core genes (Fig. 6D). Except for CTSA, all of these genes showed higher expression in hPODs (Fig. 6E,F).

Collectively, these technical validation steps confirm that our datasets are of high quality and suitable for reuse in downstream analyses and comparative studies.

Usage Notes

Our sn-RNA-seq dataset includes data from five types of PCP patients and two mouse models of POD injury, along with integrated GWAS data for MA. This comprehensive dataset offers a valuable resource for studying PCP, as it contains not only a sufficient number of PODs but also a wide range of other kidney cell types. This enables in-depth exploration of the molecular mechanisms underlying the onset and progression of PCP. All data and code used in this study are freely accessible via the links provided in the manuscript, including the Zendo database and the CKDGen Consortium. Data download and use are open. For additional data requests, please contact the corresponding author by email.

Data availability

The raw snRNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the SRA under accession numbers SRP637787 (human, https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP637787) and SRP639901 (mouse, https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP639901). The processed RDS files are available in the Zenodo database (https://zenodo.org/records/17614667). In addition, the GWAS data used in this study can be accessed and downloaded from the CKDGen Consortium database (https://ckdgen.imbi.uni-freiburg.de/datasets/Teumer_2019).

Code availability

The code designed for this study is available at “https://github.com/746443qjb/Code-for-SD”. For further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

References

Bertram, J. F., Cullen-McEwen, L. A., Andrade-Oliveira, V. & Câmara, N. O. S. The intelligent podocyte: sensing and responding to a complex microenvironment. Nature reviews. Nephrology 21, 503–516, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-025-00965-y (2025).

Puelles, V. G. et al. Human podocyte depletion in association with older age and hypertension. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology 310, F656–f668, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00497.2015 (2016).

Mann, N., Sun, H. & Majmundar, A. J. Mechanisms of podocyte injury in genetic kidney disease. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany) 40, 1523–1538, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-024-06551-x (2025).

Cunanan, J., Zhang, D., Peired, A. J. & Barua, M. Podocytes in health and glomerular disease. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 13, 1564847, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2025.1564847 (2025).

Issa, W., Njeim, R., Carrazco, A., Burke, G. W. & Mitrofanova, A. Role of the Innate Immune Response in Glomerular Disease Pathogenesis: Focus on Podocytes. Cells 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13131157 (2024).

Mitrotti, A. et al. Hidden genetics behind glomerular scars: an opportunity to understand the heterogeneity of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis? Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany) 39, 1685–1707, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-023-06046-1 (2024).

Melica, M. E. et al. Piezo1, F-Actin Remodeling, and Podocyte Survival and Regeneration. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.0000000697 (2025).

Meng, H. et al. Autoantibodies Targeting Vinculin Reveal Novel Insight into the Mechanisms of Autoimmune Podocytopathies. Research (Washington, D.C.) 8, 0722, https://doi.org/10.34133/research.0722 (2025).

Imamura, M., Kadowaki, T. & Maeda, S. Genetic studies on metabolic disorder-associated kidney diseases. Kidney international 108, 30–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2025.01.042 (2025).

Kopp, J. B. et al. Podocytopathies. Nature reviews. Disease primers 6, 68, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0196-7 (2020).

Lake, B. B. et al. An atlas of healthy and injured cell states and niches in the human kidney. Nature 619, 585–594, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05769-3 (2023).

Floege, J. et al. Management and treatment of glomerular diseases (part 1): conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney international 95, 268–280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2018.10.018 (2019).

Yang, S. et al. Decontamination of ambient RNA in single-cell RNA-seq with DecontX. Genome biology 21, 57, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-1950-6 (2020).

Lopez, R., Regier, J., Cole, M. B., Jordan, M. I. & Yosef, N. Deep generative modeling for single-cell transcriptomics. Nature methods 15, 1053–1058, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-018-0229-2 (2018).

Qing, J., Wu, J., Li, Y. & Wu, J. SCNT: An R Package for Data Analysis and Visualization of Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics. 2025.2006.2002.657520 https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.06.02.657520 bioRxiv (2025).

Zhang, L. et al. Lineage tracking reveals dynamic relationships of T cells in colorectal cancer. Nature 564, 268–272, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0694-x (2018).

Teumer, A. et al. Genome-wide association meta-analyses and fine-mapping elucidate pathways influencing albuminuria. Nature communications 10, 4130, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11576-0 (2019).

de Leeuw, C. A., Mooij, J. M., Heskes, T. & Posthuma, D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS computational biology 11, e1004219, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004219 (2015).

Lai, Q., Dannenfelser, R., Roussarie, J. P. & Yao, V. Disentangling associations between complex traits and cell types with seismic. bioRxiv: the preprint server for biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.04.592534 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP637787 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP639901 (2025).

Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15718783 (2025).

Haydak, J. & Azeloglu, E. U. Role of biophysics and mechanobiology in podocyte physiology. Nature reviews. Nephrology 20, 371–385, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-024-00815-3 (2024).

Wu, H. et al. Mapping the single-cell transcriptomic response of murine diabetic kidney disease to therapies. Cell metabolism 34, 1064–1078.e1066, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2022.05.010 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2505400), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82370717), and Key Project of Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LZ23H050001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.Q., Methodology: J.Q., Investigation: X.W., Validation: X.W., Visualization: J.Q. Formal analysis: J.Q. Funding acquisition: J.W. Project administration: J.W. Supervision: J.W. Writing—original draft: J.Q. Writing–review & editing: J.H. All authors have read and approved the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qing, J., Hu, J., Wang, X. et al. Comprehensive snRNA-Seq Datasets of Human and Mouse Podocytopathy Integrated with GWAS of Microalbuminuria. Sci Data 13, 111 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06427-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06427-1