Abstract

Fungal mitochondrial genomes are critical for understanding phylogenetics, evolution, and ecology of the Kingdom Fungi, yet they remain underrepresented in public databases. To address this, we developed a workflow to recover mitochondrial genomes from 12,902 fungal short read sequencing data housed in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) records, assembling complete circular genomes from 2,695 species. This effort expanded fungal mitochondrial genome diversity by nearly 2.3X particularly in understudied phyla such as Mucoromycota (11X increase) and Zoopagomycota (8X increase). The new dataset contains novel yet undescribed mitochondrial genomes at numerous taxonomic levels, including 15 classes, 64 orders, 178 families, and 544 genera. Taxonomic analysis revealed broad ecological representation among the top-assembled species, including human pathogens (e.g., Cryptococcus tetragattii), plant pathogens (e.g., Melampsora larici-populina), edible mushrooms (e.g., Suillus luteus), and industrial fungi. By leveraging the not yet fully exploited SRA sequencing data, this study fills critical gaps in fungal mitochondrial genomics, tripling the currently known mitochondrial genome diversity of the Kingdom Fungi, and provides an extensive resource for phylogenetic and evolutionary research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Fungi represent one of the most diverse and ecologically significant kingdoms of life, with an estimated diversity of 2 to 5 million species globally1,2. However, only approximately 150,000 species are described representing less than 5% of the total estimated diversity3. Fungal species definition has been debated for several decades as there is no consensus on how to delineate species4. With the introduction of molecular typing and DNA barcoding techniques, genomic regions like internal transcribed spacers (ITS) and 18S rRNA gene have been used extensively to molecularly type fungi and to assist in species definition. While this approach has been useful for decades, with increasing number of described species, single gene barcoding became inefficient to delineate species at high resolution. Therefore, molecular mycologists started to employ multi-locus typing and even whole genome sequencing to achieve higher taxonomic resolution, which can exceed the species-level to the sub-species level4. This is reflected currently by the increasing number of complete/draft fungal genomes deposited in different public databases5.

Fungi, like most eukaryotes, carry extrachromosomal DNA molecules, such as mitochondrial DNA or plasmids6. Those extrachromosomal DNA are present in multiple copies exceeding with order of magnitude the copy numbers of nuclear DNA. Mitochondrial genomes, with their compact size, high copy number, and conserved gene content, have been used in elucidating fungal phylogeny, population genetics, and evolutionary dynamics7,8,9,10. However, they are often ignored or advertently removed from the downstream analysis when performing whole genome sequencing of fungi11 or erroneously assembled as part of the nuclear genome12.

As of June 2024, the nucleotide database of the NCBI hosted 3,774 complete fungal mitochondrial genomes representing 1,114 species, with the majority belonging to the phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, with fewer representatives from the other phyla. In contrast, the SRA database identified 99,472 fungal genomic sequencing records, from 4,994 species, representing under-utilized resources that could potentially be used for mitochondrial genome assembly. Leveraging these gaps between the fungal mitochondrial genomes and the available public SRA records, we undertook a large-scale effort to de novo assemble complete fungal mitochondrial genomes aiming to extend the current mitochondrial diversity to new groups. To achieve this, we employed a fungal mitochondrial genomes recovery workflow that involves quality control check, followed by de novo assembly from paired end (PE) short reads, and extraction of mitochondrial genomes (Methods).

In conclusion, this dataset significantly expanded the known diversity of fungal mitochondrial genomes by leveraging underutilized public sequencing data, successfully assembling complete mitochondrial genomes from 2,695 species—nearly tripling the previously available records. The dataset introduced the first mitochondrial genomes for numerous taxonomic groups, including 15 classes, 64 orders, 178 families, and 544 genera, with particularly notable expansions in understudied phyla such as Mucoromycota (11X) and Zoopagomycota (8X). By filling critical gaps in fungal mitochondrial genomics, this resource enables deeper phylogenetic, ecological, and evolutionary studies, while also providing a foundation for future research on fungal biodiversity, host-pathogen interactions, and mitochondrial evolution. The workflow and findings underscore the value of mining public sequencing data to unlock hidden genomic diversity, presenting a model for similar large-scale efforts in other eukaryotic lineages.

Methods

Data collection

Fungal mitochondrial genomes

To retrieve the already available complete mitochondrial genomes of the Kingdom Fungi, we used the NCBI online platform querying for “mitochondrion[Title] AND (“complete genome” OR “complete sequence”)” then applied the following filters: i) species == “fungi”; ii) molecule type == “genomic DNA”; iii) sequence type == “Nucleotide”; and iv) genetic compartment == “Mitochondrion”. The resulting records were exported to a sequence file in FASTA format.

Fungal SRA records

To check the available fungal short reads SRA records, we queried for “fungi” in the SRA database, then applied the following filters: i) source == “DNA”; ii) library layout == “paired”; iii) platform == “Illumina”; iv) strategy == “genome”; and v) file type == “fastq”. The resulting records were exported as a TSV file including all associated metadata.

To exclude the SRA records from species with already existing complete mitochondrial genomes, we mapped the accession numbers of the fungal mitochondrial genomes and the SRA accessions to the NCBI taxonomy database13, using the R package “taxonomizr” v0.10.7 (https://github.com/sherrillmix/taxonomizr). For each mitochondrial genome accession number, we used the function “accessionToTaxa” to get its taxonomic ID (taxID), then we used the function “getTaxonomy” to get the taxonomic lineage. We considered only the major taxonomic ranks i.e., kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. For the SRA records, we applied the function “getTaxonomy” directly on the taxID associated with each BioSample.

Then, all SRA records with representative mitochondrial genomes available, either in RefSeq or in the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC) were excluded and the remaining SRA accessions were used for further de novo assembly.

Mitochondrial genome assembly workflow

For each SRA record, we downloaded the raw sequencing data in fastq format using the tool “fasterq-dump” v3.0.1 (https://github.com/ncbi/sra-tools), then trimmed the adapters and low-quality sequences using “fastp” v0.23.414 applying the default parameters. The resulting files were rarefied to 5 million paired end reads using “seqtk” v1.4 (r122) (https://github.com/lh3/seqtk); followed by de novo assembly using “SPAdes” v4.0.115 with the options “--gfa11 -k 21,33,55,77,89 --isolate”. To extract the mitochondrial genomes from the resulting assembly graphs, we used the tool “GetOrganelle” v1.7.7.116, specifying the search database “fungus_mt” to confine the search to fungal mitochondrial genomes. The tool labels the extracted mitochondrial genomes as complete and circular or as scaffolded genomes. For the scaffolded genomes, we repeat the process of rarefaction and the assembly but using 2 million paired end reads (Fig. 1).

Mitochondrial genome annotation and phylogeny

The assembled complete mitochondrial genomes as well as those retrieved from the RefSeq and the INSDC were annotated using “MFannot” v1.3717, using their corresponding genetic code.

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the amino acid sequences of the mitochondrial protein-coding genes (PCGs) cox1, cox2, cox3, cob, nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, nad6, atp6, atp8, and atp9. The sequences for each gene were aligned using “MAFFT” v7.50518, and poorly aligned regions were trimmed using “trimAl” v1.4.rev2219, followed by concatenation and alignment assessment using “AMAS” (https://github.com/marekborowiec/AMAS)20. A maximum-likelihood phylogeny was inferred with “FastTreeMP” v2.1.1121 under the LG + Γ model (Le & Gascuel amino acid substitution matrix with gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity). Branch lengths represent the number of substitutions per site, and node support values were estimated using FastTree’s approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-like local support). The tree was rooted with the phylum Rozellomycota (including 2 genomes), using the R package “castor” and visualized and annotated using the R packages “ggtree” and “ggtreeExtra”.

Data Records

Nucleotide sequence data reported are available in the Third Party Annotation Section of the DDBJ/ENA/GenBank databases under the BioProject PRJNA1367877 and the accession numbers TPA: BK072095-BK07478922.

Additionally, the following data files are available in Figshare23:

-

1.

“Assembled_fungal_mitochondrial_genomes.fasta”: Combined FASTA file including all newly assembled mitochondrial genomes.

-

2.

“fungal_mitochondrial_genomes_phylogeny.tre”: Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of all fungal mitochondrial genomes. The analysis includes all fungal complete mitochondrial genomes assembled in this study as well as genomes from the RefSeq and the INSDC databases.

-

3.

“All_fungal_mitochondrial_genomes_accessions.tsv”: Table including NCBI accession numbers and taxonomic information of the newly assembled mitochondrial genomes as well as their corresponding BioProject accession, BioSample accession, and PubMed references (when available). The table additionally includes the accession numbers of the already existing mitochondrial genomes from the RefSeq and INSDC databases. For all records, genome sizes and GC content is provided.

Technical Validation

To validate the newly assembled mitochondrial genomes, we followed three strategies. First, we considered the genomes complete if they were identified by GetOrganelle16 as circular and complete. Second, after annotation with MFannot17, we set an empirical threshold for completeness based on the presence of a minimum number of core protein-coding genes (PCGs) at certain taxonomic ranks. While fungal mitochondrial genomes have no known set of core genes24, a typical fungus will contain 4 gene complexes, i.e., complex I (nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, and nad6), complex III (cob), complex IV (cox1, cox2, and cox3), and complex V (atp6, atp8, atp9)6. Based on the RefSeq mitochondrial genome annotations, we used different completeness thresholds for different taxonomic ranks (down to the order-level) as follows: 1) The orders of Saccharomycetales, Saccharomycodales, and Schizosaccharomycetales of Ascomycota should include at least 7 genes; 2) The order Pezizales of Ascomycota, to include at least 8 genes; 3) The phylum Chytridiomycota (orders Caulochytriales and Cladochytriales), to include at least 11 genes; 4) The order Lobulomycetales of Chytridiomycota to include 12 genes; 5) The orders Acrospermales, Aulographales, Eremomycetales, Jahnulales, Microthyriales, Mytilinidiales, Phaeotrichales, Pleosporales, and Venturiales of Ascomycota to include at least 12 genes; 6) The orders Pucciniales, Septobasidiales, and Urocystidales of Basidiomycota to include at least 13 genes; 7) and finally the remaining orders of Fungi to include 13 genes at least.

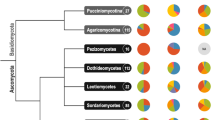

Finally, we used only the genomes that passed the previous filters and used them for phylogenetic overview, including genomes from the NCBI RefSeq and the INSDC databases (Fig. 2). The constructed phylogenetic tree included a total of 4,012 genomes providing a comprehensive overview of the Kingdom Fungi. The newly assembly genomes fell within the expected clades compared with the RefSeq and INSDC genomes.

(a) Proportion of fungal mitochondrial genomes from different sources. (b) Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of fungal mitochondrial genomes. The analysis includes all fungal complete mitochondrial genomes assembled in this study as well as species representatives from the RefSeq and the INSDC databases. The phylogeny was inferred with FastTreeMP from concatenated mitochondrial protein sequences (cox1, cox2, cox3, atp6, atp8, atp9, cob, nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5 and nad6) under the LG + Γ model. Branch lengths represent the number of substitutions per site. Node support values were estimated using FastTree’s approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-like local support) but are not shown (79% of the nodes are supported with >70%, for details please refer to the dataset file “fungal_mitochondrial_genomes_phylogeny.tre”). The tree was rooted with the phylum Rozellomycota (including 2 genomes). The colors of the tree tips refer to the phylum of origin while the colors of the outer ring refer to the source database. (c) The phylogenetic tree of the panel (b) collapsed at the phylum level to provide a comprehensive overview on the Kingdom Fungi, using the latest taxonomic proposal25. The red dots refer to the branches supported by >70%.

Code availability

The assembly workflow was implemented in a python script (assembly_workflow.py) passing SRA run accession as input and outputting the assembly contigs and graphs, which are used by GetOrganelle for mitochondrial genome extraction (Methods). The script uses already published tools and explained in the Methods section. The script is available on GitHub at https://github.com/msabrysarhan/fungal_mtDNA.

Data availability

Nucleotide sequence data reported are available in the Third Party Annotation Section of the DDBJ/ENA/GenBank databases under the BioProject PRJNA1367877 and the accession numbers TPA: BK072095-BK074789, and the metadata is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28750034.

References

Hawksworth, D. L. & Lücking, R. J. M. s. Fungal diversity revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 million species. 5, https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec. funk-0052-2016 (2017).

Paterson, R. R. M., Solaiman, Z. & Santamaria, O. J. S. R. Guest edited collection: fungal evolution and diversity. 13, 21438 (2023).

James, T. Y., Stajich, J. E., Hittinger, C. T. & Rokas, A. J. A. R. O. M. Toward a fully resolved fungal tree of life. 74, 291-313 (2020).

Chethana, K. T. et al. What are fungal species and how to delineate them? 109, 1-25 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. A genome-scale phylogeny of the kingdom Fungi. 31, 1653-1665. e1655 (2021).

Kouvelis, V. N., Kortsinoglou, A. M., James, T. Y. J. E. o. F. & Organisms, F.-L. The evolution of mitochondrial genomes in fungi. 65-90 (2023).

Kulik, T., Van Diepeningen, A. D. & Hausner, G. J. F. i. M. Vol. 11 628579 (Frontiers Media SA, 2021).

Song, N., Geng, Y. & Li, X. J. F. i. M. The mitochondrial genome of the phytopathogenic fungus Bipolaris sorokiniana and the utility of mitochondrial genome to infer phylogeny of Dothideomycetes. 11, 863 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. Dynamic evolution of eukaryotic mitochondrial and nuclear genomes: a case study in the gourmet pine mushroom Tricholoma matsutake. 23, 7214-7230 (2021).

Sauters, T. J. & Rokas, A. J. C. B. Patterns and mechanisms of fungal genome plasticity. 35, R527-R544 (2025).

Jung, H. et al. Twelve quick steps for genome assembly and annotation in the classroom. 16, e1008325 (2020).

Persoons, A. et al. Patterns of genomic variation in the poplar rust fungus Melampsora larici-populina identify pathogenesis-related factors. 5, 450 (2014).

Schoch, C. L. et al. NCBI Taxonomy: a comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools. 2020, baaa062 (2020).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 (2018).

Nurk, S., Meleshko, D., Korobeynikov, A. & Pevzner, P. A. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome research 27, 824–834 (2017).

Jin, J.-J. et al. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biology 21, 241, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02154-5 (2020).

Lang, B. F. et al. Mitochondrial genome annotation with MFannot: a critical analysis of gene identification and gene model prediction. 14, 1222186 (2023).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30, 772–780, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst010 (2013).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. J. B. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. 25, 1972-1973 (2009).

Borowiec, M. L. J. P. AMAS: a fast tool for alignment manipulation and computing of summary statistics. 4, e1660 (2016).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. J. P. O. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. 5, e9490 (2010).

Sarhan, M. S., Abdalrahem, A., Maixner, F. & Fuchsberger, C. NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/bioproject:PRJNA1367877 (2025).

Sarhan, M. S., Abdalrahem, A., Maixner, F. & Fuchsberger, C. De novo assembly of complete circular mitochondrial genomes from 2,695 fungal species. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28750034 (2025).

Fonseca, P. L. et al. Global characterization of fungal mitogenomes: new insights on genomic diversity and dynamism of coding genes and accessory elements. 12, 787283 (2021).

Wijayawardene, N. N. et al. Classes and phyla of the kingdom Fungi. 128, 1-165 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the “MOC - MultiOmics Centre for Food and Health” project. The MOC project is co-funded by the European Union (European Regional Development Fund - EFRE). Ammar Abdalrahem was supported by a PhD fellowship from the French Ministry of Education and Research (MESR) and by the French Plan Investissement d’Avenir (PIA) Lab of Excellence ARBRE [ANR-11-LABX-0002- 01]. The authors thank the Department of Innovation, Research and University of the Autonomous Province of Bozen/Bolzano, Italy for covering the Open Access publication costs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.S. conceived the original idea. M.S.S. and A.A. designed and performed the computational analysis. M.S.S. performed the data visualization and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. M.S.S. and A.A. curated the data for public deposition. F.M. and C.F. edited and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarhan, M.S., Abdalrahem, A., Maixner, F. et al. De novo assembly of complete circular mitochondrial genomes from 2,695 fungal species. Sci Data 13, 28 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06447-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06447-x