Abstract

A chromosome-level genome assembly of Bohadschia ocellata, a member of the Holothuriidae family, was constructed through the integration of MGI DNBSEQ-T7 short-read sequencing, PacBio HiFi long-read sequencing, and Hi-C genomic scaffolding technology. After optimization to eliminate redundant sequences, the genome assembly was precisely anchored to 23 chromosomes, resulting in a total size of 909.18 Mb. The N50 of its contig and scaffold sequences were 12.00 Mb and 38.97 Mb, respectively, confirming that the assembly was highly continuous. According to Merqury and BUSCO evaluations, the genome assembly reached a QV of 64.44 and completeness of 94.40%. From this assembly, 31,277 protein-coding genes were identified, which were 98.10% complete based on BUSCO assessment of the predicted proteome. Functional annotations were obtained from at least one database for more than 99% of these genes. This high-quality B. ocellata genome assembly from the current study could offer valuable information for further genetic and evolutionary studies of this sea cucumber species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Sea cucumbers, belonging to the class Holothuroidea within the phylum Echinodermata1, comprise more than 1,800 species2 and possess the second highest diversity among echinoderms3. They typically inhabit coral reefs, rocky substrates or deep sea bottoms4. While most sea cucumbers primarily distribute in the Indo-Pacific, they are considered highly valuable in the region, with up to 80 species being commercially harvested5. Such scale of exploitation is largely due to their price as luxury commodity and high nutritional value, which made them particularly popular in Asian cuisines6. Therefore, it’s unsurprising that most commercial sea cucumbers are tropical members of the families Holothuriidae and Stichopodidae, with only some temperate species from the family Cucumariidae7. Ecologically, sea cucumbers also play at least four important roles including the: 1) recycling of nutrients, 2) facilitating bioturbation and deposit-feeding, 3) disturbing sediments to promote mineralization 4) influencing seawater chemistry8,9. Currently, however, seven species of sea cucumbers have been recognized as “Endangered” and nine as “Vulnerable” on the IUCN Red List10. This is caused by persistent overfishing, drastically depleting many high-value sea cucumber populations, such as Holothuria Scabra11. Thus, the practice of artificial breeding and stock enhancement as a critical means of managing sea cucumbers fisheries and aquaculture has become increasingly applied12,13,14.

Bohadschia ocellata is a sea cucumber species of the family Holothuriidae natively found in a wide range across the tropical Indo-Pacific, including the Timor Sea, South China Sea, Philippine Sea and the Great Barrier Reef5 (Fig. 1a). In the Persian Gulf, as a species of great density, it’s particularly recorded for great reproduction and growth rate15. The large, blotchy spots on the dorsum serve as a symbolic trait for identifying the species16. While behaviourally, B. ocellata is often noticed as exposed during the day, although it is capable of burrowing and can frequently be found buried in the sand16. In Asian regions, especially in China, the body wall of B. ocellata is commonly consumed10. Furthermore, the fucosylated chondroitin sulfate extracted from B. ocellata contains key monosaccharide components and demonstrates significant biological activities17. As a result, overfishing and habitat destruction have led to a sharp decline in B. ocellata populations over the past decade.

Samyn, Y and Vandenspiegel, D have examined the holotype of B. ocellata and concluded it to be a valid species of the genus Bohadschia18. Therefore, the earlier classification of B. ocellata into the genus Holothuria was proposed as unjustified19. With continuous progress of sea cucumber taxonomy, both Holothuria and Bohadschia have now been confirmed as independent and valid genera. Meanwhile, based on morphological characteristics and mitochondrial genome sequencings, B. ocellata has been reclassified into the genus Bohadschia16,20, forming a species different from the established Holothuria ocellata21. Although the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene of B. ocellata was successfully sequenced22, the lack of a whole-genome assembly to this day obstacles the more comprehensive study of its phylogenetic affinity, taxonomy and evolutionary process.

To date, chromosome-level genomes have been reported for a few Holothurian species, such as Apostichopus japonicus23, Holothuria leucospilota24, H. scabra25, Stichopus monotuberculatus26 and Chiridota heheva27. However, whole-genome data for sea cucumbers within the genus Bohadschia remain scarce28. In this study, to fill this gap, PacBio Revio long-read sequencing, MGI DNBSEQ-T7 short-read sequencing and Hi-C mapping were employed to assemble a high-quality chromosome-level genome of B. ocellata. A final genome assembly of 909.18 Mb was obtained and mapped onto 23 pseudochromosomes, with contig and scaffold N50 values of 12.00 Mb and 38.97 Mb, respectively. A total of 31,277 protein-coding genes were identified in the B. ocellata genome, displaying a completeness of 98.10% according to BUSCO assessment of the predicted proteome. Over 99% (30,752) of the genes received functional annotations from at least one database. This chromosome-level genome assembly of B. ocellata not only serves as a valuable genomic resource for further studying the classification and radiation within Bohadschia, but also constructs a worthwhile foundation for future discovering of its evolutionary adaptations, gene functions and conservation strategies.

Methods

Sample collection and nucleic acid extraction

All sea cucumber samples used for sequencing in this study were harvested from Tanmen Port (19.33° N, 110.49° E), Qionghai City, Hainan Province and one was randomly collected at the site to dissect its muscles. The excised muscle tissue was rinsed in a dish containing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and immediately transferred to liquid nitrogen. The QIAamp DNA Min Kit was used to extract high-quality DNA from muscle for whole-genome sequencing using both the long-read and short-read approaches.

In the same manner as above, scissors and forceps were used to carefully separate 6 tissues, including intestine, muscle, oral tentacles, respiratory tree, testis and rete mirabile. Total RNA was extracted from the listed 6 tissues for transcriptomic sequencing using the RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (Tiangen Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

Library preparation and sequencing

Short-read sequencing was performed using the MGI DNBSEQ-T7 platform with a read length configuration of PE150. High-quality DNA that has completed the purity, concentration and integrity tests, is sheared with the help of fragmentase. Then, the fragmented DNA is end-repaired dA-tailed and connected to sequencing adapters. To construct a paired-end library with 350 bp insert, MGIEasy FS DNA Library Preparation Kit (MGI, Shenzhen, China) was used for restriction fragmentation and sequencing adapter ligation. The combined libraries were used to prepare DNA nanoballs (DNBs) through rolling circle replication technology, which were subsequently used for sequencing. The obtained raw data were evaluated and filtered using FastQC (v0.12.1) and SOAPnuke (v2.1.4)29 tools. Acquisition of 73.74 Gb of short-read data were achieved, corresponding to an 81.10 × coverage (Table 1).

Long-read sequencing was carried out using the PacBio Revio platform (Pacific Biosciences). Isolation of high-quality DNA using the QIAamp DNA Min Kit. The fragmented DNA was then end-repaired and A-tailed using SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 (PacBio, Menlo Park, CA, USA). Finally, adapters were connected to both ends of the fragments. After BluePippin size screening, Sequel II Binding Kit 3.2 (PacBio, Menlo Park, CA, USA) was used to bind sequencing polymerase to the constructed library and it was loaded onto the SMRT Cell 8 M sequencing reagent plate for sequencing. SMRT Link v13.1 (Pacific Biosciences) was used to convert each polymerase read with a complete adapter into a Circular Consensus Sequence read (CCS), which was saved in read.bam and filtered according to the QV > = 2030 standard to obtain the final valid data. Acquisition of 53.85 Gb of long-read data were obtained, corresponding to a 59.23 × coverage (Table 1).

High-throughput Hi-C sequencing was also implemented using the MGI DNBSEQ-T7 platform with a sequencing read length of PE150. Formaldehyde fixation and subsequent digestion with the DPNII enzyme (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) were applied to muscle samples. After end-repair, biotin labeling and fragment connection, the extracted DNA will be decrosslinked and broken into fragments of approximately 350 bp. The capture of DNA fragments with interactive relationships is facilitated by streptavidin magnetic beads, enabling library construction. Quality assessment of the library’s concentration and insert size was conducted using Qubit 3.0 and Agilent 2100, followed by sequencing of the qualified samples. The raw data were evaluated using FastQC (v0.12.1) software, resulting in 142.18 Gb (156.39 × coverage) of clean data (Table 1).

Utilizing the Illumina high-throughput sequencing platform, transcriptome sequencing was undertaken. While mRNA was enriched from total RNA and purified using AMPure XP beads, it was subsequently reverse transcribed to cDNA, which subsequently underwent end- repair, A-tailing and adapter ligation. PCR amplification was performed on the screened fragments to construct the library and its quality and effective concentration were assessed using AATI and qPCR. Sample-specific barcode primers were used to label the constructed libraries, which were subsequently pooled, followed by paired-end sequencing to generate raw data from the original six tissue samples. The ultimate generation of clean data amounted to 42.30 Gb (Table 1).

Genome assessment and assembly

Assessment of genome size, heterozygosity and repetitive sequence content was conducted through k-mer analysis. 21-mers were counted from raw sequencing reads using Jellyfish (version 2.3.0)31, which utilized 10 threads and counted both strands. The k-mer size was set to 21, and the hash size was set to 100 MB (Fig. 1b; Table 2). GenomeScope (version 2.0)32 was employed to analyze the k-mer histograms generated by Jellyfish, using a k-mer size of 21 and assuming a ploidy level of 2. Following the elimination of k-mers with erroneous frequencies, 37,990,663,645 k-mers showing a main peak at depth 65.40 were retained (Table 2). In k-mer analysis, the first, taller peak represents homozygous regions, while the second, smaller peak corresponds to heterozygous regions. GenomeScope estimated a genome size of ~802.34 Mb for B. ocellata, with 27.60% repetitive content. The analysis confirms that the genome of B. ocellata has a high heterozygosity rate, estimated at approximately 1.78%. Other sea cucumber species, such as H. leucospilota24 and S. monotuberculatus26, also exhibit this phenomenon.

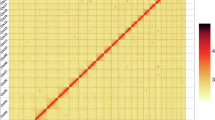

PacBio HiFi long-reads were employed for assembly using hifiasm (v0.19.8-r603)33 software. Preliminary contigs generated through all-versus-all alignment of overlapping reads were subjected to three rounds of iterative self-correction, thereby optimizing sequence accuracy and producing high-confidence contigs. Purge_dups (v1.2.5)34 facilitated the removal of redundant sequences from the preliminary assembly, enabling the completion of the draft genome. MGI short-reads were aligned to the de-redundant genome using Bwa (v0.7.17-r1188)35 and based on this alignment base correction and gap filling was performed by Pilon (v1.23)36. Based on the interactions in the Hi-C matrix, scaffolds were clustered and assigned to chromosomal positions. Subsequent sequencing and orientation were performed using ALLHIC (v1.1)34, culminating in a chromosome-scale assembly comprising 23 pseudochromosomes with 97.27% of scaffolds anchored (Fig. 1c). To interpret the various genomic features and their distribution along chromosomes (Fig. 2; Table 3), a circos plot depicting the genome structure was constructed using Circos (v0.69.8)37. The visualization included the following tracks from inner to outer circles: chromosomes, gene regions, repeat sequences, SNP percentage and NGS sequencing depth. The final genome assembly comprised 73 scaffolds spanning 909.18 Mb, with a scaffold N50 of 38.97 Mb and contig N50 of 12.00 Mb (Table 4).

Repetitive element annotation

RepeatMasker (version 4.09 with RepBase 20181026)38 and EDTA39, a whole-genome de-novo transposable element annotation pipeline, were employed to generate high-quality TE annotations. The EDTA pipeline, comprising LTRharvest, the parallel version of LTR_FINDER, LTR_retriever, GRF, TIR-Learner, HelitronScanner, RepeatModeler and customized filtering scripts, is designed to construct a candidate repeat sequence library. The subsequent application of nucleotide coding sequences (CDS) contributes to filter out gene-like sequences from the TE library and eliminates redundancy by consolidating results from the three methods mentioned above. A total of 34.31% of the assembled genome was identified as repetitive, among which DNA elements accounted for the highest proportion (13.57%), followed by LINEs (4.33%), LTRs (0.91%), SINEs (0.02%) and simple repeats (0.01%) (Fig. 3a; Table 5).

Noncoding RNA annotation

Ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) and transfer RNAs (tRNAs) were predicted using default parameters by Barrnap (v0.9)40 and tRNAscan-SE (v2.0.11)41, respectively. The identification of other non-coding RNAs, such as small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs), was achieved through alignment with the Rfam database (v14.8)42, followed by annotation using Infernal (v1.1.4)43. A total of 20 miRNAs, 9,079 tRNAs, 533 rRNAs and 1,785 snRNAs were identified in the genome of B. ocellata (Fig. 3b; Table 6).

Gene prediction and functional annotation

To enhance exon–intron structure recognition and to optimize gene prediction models, RNA-seq reads were incorporated into the annotation process, followed by evidence integration from multiple sources using MAKER3 (v3.01.03)44 for functional annotations. A total of 42.30 Gb of RNA-seq data were obtained through the sequencing of transcriptomes from six tissues of B. ocellata for use in gene annotation (Table 7). HISAT2 (v2.2.1)45 was used to align the cleaned RNA-seq reads to the assembled genome, after which StringTie (v2.1.7)46 was utilized to reconstruct transcript structures and quantify expression levels. The incorporation of 9 high-quality protein datasets facilitated homology-based functional annotation, including those from Lytechinus pictus (GCF_015342785.2), Patiria miniata (GCF_015706575.1), Anneissia japonica (GCF_011630105.1), Asterias rubens (GCF_902459465.1), Acanthaster planci (GCF_001949145.1), Lytechinus variegatus (GCF_018143015.1), Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (GCF_000002235.5), H. leucospilota (GCA_029531755.1) and A. japonicus (GCA_002754855.1). Using BRAKER3 (v3.0.8), which synergistically combines GeneMark-ETP + and AUGUSTUS47, gene models were predicted and annotated in an unsupervised and evidence-guided manner. By simultaneously leveraging RNA-seq expression profiles and protein orthology, this strategy enables the comprehensive annotation of both well-supported coding regions and novel gene models. Genome from three other Holothuroidea species—H. leucospilota24, A. japonicus23 and S. monotuberculatus26—were compared with the predicted genes of B. ocellata in terms of gene count and genomic features, with a total of 31,277 genes identified in B. ocellata (Table 8). BUSCO analysis using 954 single-copy orthologs from 65 genomes indicated that 98.10% of genes were complete and only 0.90% were fragmented, indicating the completeness of the annotated gene set (Table 9).

Functional annotation and amino acid sequence analysis were conducted using InterProScan (v5.56)48 to predict protein families, domains and functional sites. Additionally, the amino acid sequences of the genes were compared with the UniProt49, UniProtKB/SwissProt50 and KEGG51 databases using the BLAST (v2.12.0+, e-value 1e−5)52 tool to confirm their functional information and the biological pathways involved. Gene Ontology (GO)53 annotations were obtained from InterProScan output, detailing the molecular functions, cellular components and biological processes associated with each gene. The results showed that a total of 30,752 protein sequences (99%) were annotated with at least one public database (Fig. 4; Table 10).

Data Records

All sequence reads and chromosome-level genome assembly of B. ocellata associated with this project are available under SRP58693854 at NCBI. The whole genome shotgun project has been deposited in DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession number JBOCEH00000000055, which corresponds to the version described in this paper. The genome sequencing datasets, including PacBio HiFi (SRR33662152)56, BGI short-reads (SRR33662151)57 and Hi-C reads (SRR35940911)58, are publicly accessible via the SRA. Additionally, RNAseq data is available under SRA numbers SRR33662153–SRR3366215859,60,61,62,63,64. Additional related datasets, including genome assembly, gene annotation and functional annotation are available in the Figshare repository65 or Baiduyun66.

Technical Validation

Nucleic acid quality

After assessing the quality and concentration of DNA using 0.70% agarose gel electrophoresis, NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), DNA samples showing slight degradation were considered suitable for sequencing library preparation. The concentration, integrity and purity of RNA were assessed using NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), Bioanalyzer 5400 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis (0.70%), respectively. RNA samples exhibiting a RIN above 9.50 were considered suitable for downstream library preparation.

Genome assembly and annotation quality

The QV pipeline of Merqury67 was used to estimate the assembly QV based on k-mer analysis. Using the “best_k.sh” script from Merqury, the optimal k-mer length was calculated as 19. The number of k-mers in the short-read sequencing data was calculated using Meryl with default settings and the output was then used alongside the assembly in Merqury to perform the QV evaluation. A k-mer completeness of 78.25% and a k-mer-based QV of 64.44 were obtained from the analysis.

BUSCO analysis was performed to further evaluate genome completeness, utilizing the metazoa_odb10 dataset, which includes 954 conserved genes from 65 metazoan genomes. BUSCO evaluation indicated an overall completeness of 98.20%, consisting of 94.40% complete BUSCOs, 3.80% fragmented and 1.80% missing (Table 11). The BUSCO assessment indicated that the majority of core, essential genes were captured in the assembly or annotation, supporting the high quality, completeness and accuracy of the B. ocellata genome, which provides a valuable genomic foundation for resource conservation, selective breeding, and aquaculture development.

Data availability

All sequencing and assembly data generated in this study have been deposited in public repositories. Raw sequencing data including BGI short-reads, PacBio HiFi long-reads, Hi-C reads and RNA-seq data are available at NCBI Sequence Read Archive database under the number SRP58693854 (https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP586938). The whole genome shotgun project has been deposited in the DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession number JBOCEH00000000055 (https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBOCEH000000000). Additionally, the genome assembly, gene annotation and functional annotation are available in the Figshare repository65 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29124434.v1) or Baiduyun66 (https://pan.baidu.com/s/10DBoB_GQQhThYBiloGInsA?pwd=wmhs).

Code availability

All commands and workflows used for data processing were executed in accordance with the respective software manuals and protocols, with the relevant settings and parameters detailed below:

SOAPnuke (v2.1.4): Employed to filter out low-quality reads from MGI raw sequencing data using the software’s default configurations.

SMRT Link (v13.1): Employed to process and filter PacBio raw sequencing data using default configurations.

Jellyfish (v2.3.0): Utilized to count 21-mers for estimating genome size and heterozygosity.

GenomeScope (v2.0.0): Utilized to process the K-mer frequency histogram for estimating genome size, heterozygosity, and repeat content using default configurations.

Hifiasm (v0.19.8-r603): Utilized to assemble the PacBio HiFi data after reads comparison and self-correct using built-in configurations.

Bwa (v0.7.17-r1188): Utilized to map the MGI short read data onto the draft assembly using built-in configurations.

Pilon (v1.23): Utilized to correct residual errors with Bwa alignment result using built-in configurations.

Purge_dups (v1.2.5): Utilized to reduce redundant haplotigs and determine heterozygosity for the draft genome under a configuration of -j 80 -s 80.

ALLHiC (v1.1): Utilized to assign and orient scaffolds using Hi-C reads into chromosome-level assemblies.

Merqury (v1.3): Utilized to assess k-mer coverage and QV value for the qualification of the assembled genome using best-fit K-mer = 19.

BUSCO (v5.7.1): Utilized to estimate genomic coverage using the metazoa_odb10 data collection.

Circos (v0.69): Utilized to display chromosomal structure and visualize the distribution of gene regions, repeat sequences, SNP percentage and NGS sequencing depth.

RepeatMasker (v4.09): Utilized to annotate transposable elements using built-in configurations.

EDTA: Utilized to annotate de-novo transposable elements using built-in configurations.

Barrnap (v0.9): Utilized to identify ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) using built-in configurations.

tRNAscan-SE (v2.0.11): Utilized to search for transfer RNAs (tRNAs) sing built-in configurations.

Infernal (v1.1.4): Utilized to identify microRNAs (miRNAs) and small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) using built-in configurations.

Braker (v3.0.8): Utilized to integrate gene prediction results with 9 selected proteomes and RNAseq reads from tissues with parameters set to gff3, threads 48, prot_seq = pep.fasta, bam = bams and UTR = on.

HISAT2 (v2.2.1): Utilized to map transcriptomic data for genome annotation using built-in configurations.

StringTie (v2.1.7): Utilized to assemble the transcripts for the prediction of gene structures using built-in configurations.

MAKER3 (v3.01.03): Utilized to combine outputs from various prediction modes into the final gene collection using built-in configurations.

BLAST (v2.11.0 +): Employed for synteny analysis and functional annotation of predicted genes using the BLASTP module with an E-value threshold of 1e–⁵.

References

Mercier, A., Gebruk, A., Kremenetskaia, A. & Hamel, J-F. in The World of Sea Cucumbers (ed. Mercier, A., Hamel, J-F., Suhrbier, A. D. & Pearce, C. M.) Ch. 1, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-95377-1.00001-1 (London Academic Press, 2023).

Mercier, A. et al. Revered and Reviled: The Plight of the Vanishing Sea Cucumbers. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 17, 115–142, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-032123-025441 (2025).

Miller, A. K. et al. Molecular phylogeny of extant Holothuroidea (Echinodermata). Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 111, 110–131, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2017.02.014 (2017).

Pearce, C. M., William Gartrell, J., King, X. K. & Zaklan Duff, S. D. in The World of Sea Cucumbers (ed. Mercier, A., Hamel, J-F., Suhrbier, A. D. & Pearce, C. M.) Ch. 2, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-95377-1.00014-X (London Academic Press, 2023).

Purcell, S. W. et al. Commercially important sea cucumbers of the world 2nd edn, https://doi.org/10.4060/cc5230en (FAO, 2023).

Gamboa, R. U., Halun, S. Z. B. & Vularika, A. S. in The World of Sea Cucumbers (ed. Mercier, A., Hamel, J-F., Suhrbier, A. D. & Pearce, C. M.) Ch. 9, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-95377-1.00021-7 (London Academic Press, 2023).

Conand, C. Tropical sea cucumber fisheries: Changes during the last decade. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 133, 590–594, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.05.014 (2018).

Slater, M. in The World of Sea Cucumbers (ed. Mercier, A., Hamel, J-F., Suhrbier, A. D. & Pearce, C. M.) Ch. 41, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-95377-1.00022-9 (London Academic Press, 2023).

Wolfe, K. in The World of Sea Cucumbers (ed. Mercier, A., Hamel, J-F., Suhrbier, A. D. & Pearce, C. M.) Ch. 28, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-95377-1.00028-X (London Academic Press, 2023).

Phelps Bondaroff, T. N. & Morrow, F. in The World of Sea Cucumbers (ed. Mercier, A., Hamel, J-F., Suhrbier, A. D. & Pearce, C. M.) Ch. 13, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-95377-1.00009-6 (London Academic Press, 2023).

Hamel, J. F. et al. Global knowledge on the commercial sea cucumber Holothuria scabra. Adv. Mar. Bio. 91, 1–286, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.amb.2022.04.001 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Pipeline for identification of genome-wide microsatellite markers and its application in assessing the genetic diversity and structure of the tropical sea cucumber Holothuria leucospilota. Aquaculture Reports. 37, 102207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102207 (2024).

Nocillado, J. et al. Spawning induction of the high-value white teatfish sea cucumber, Holothuria fuscogilva, using recombinant relaxin-like gonad stimulating peptide (RGP). Aquaculture. 547, 737422, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737422 (2022).

Osathanunkul, M. & Suwannapoom, C. Sustainable fisheries management through reliable restocking and stock enhancement evaluation with environmental DNA. Sci. Rep. 13, 11297, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38218-2 (2023).

Javanmardi, S., Rezaei Tavabe, K., Moradi, S. & Abed-Elmdoust, A. The effects of dietary levels of the sea cucumber (Bohadschia ocellata Jaeger, 1833) meal on growth performance, blood biochemical parameters, digestive enzymes activity and body composition of Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei Boone, 1931) juveniles. Iranian Journal of Fisheries Sciences. 19, 2366–2383, https://doi.org/10.22092/ijfs.2020.122330 (2020).

Kim, S. W., Kerr, A. M. & Paulay, G. Colour, confusion, and crossing: resolution of species problems in Bohadschia (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 168, 81–97, https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12026 (2013).

Thinh, P. D. et al. Fucosylated Chondroitin Sulfate from Bohadschia ocellata: Structure Analysis and Bioactivities. Processes. 12, 2108, https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12102108 (2024).

Samyn, Y. & Vandenspiegel, D. Sublittoral and bathyal sea cucumbers (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea) from the Northern Mozambique Channel with description of six new species. Zootaxa. 4196, 451–497, https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4196.4.1 (2016).

Liao, Y. & Clark, A. M. The Echinoderms of Southern China (Science Press, Beijing & New York, 1995).

Amin, A. & Thalib, B. Marine of dentistry: pemanfaatan stichopus hermanii dalam bidang kedokteran gigi (Nas Media Pustaka Press, Indonesia, 2024).

Cheng, H. et al. Taxonomic status and phylogenetic analyses based on complete mitochondrial genome and microscopic ossicles: Redescription of a controversial tropical sea cucumber species (Holothuroidea, Holothuria Linnaeus, 1767). Zoosyst. Evol. 101, 791–804, https://doi.org/10.3897/zse.101.137781 (2025).

Patantis, G., Dewi, A. S., Fawzya, Y. N. & Nursid, M. Identification of Beche-de-mers from Indonesia by molecular approach. Biodiversitas. 20, 537–543, https://doi.org/10.13057/BIODIV/D200233 (2019).

Sun, L., Jiang, C., Su, F., Cui, W. & Yang, H. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Sci. Data. 10, 454, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02368-9 (2023).

Chen, T. et al. The Holothuria leucospilota genome elucidates sacrificial organ expulsion and bioadhesive trap enriched with amyloid-patterned proteins. Pnas. 120, e2213512120, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2213512120 (2023).

Zhong, S. et al. Chromosomal-level genome assembly and annotation of the tropical sea cucumber Holothuria scabra. Sci. Data. 11, 474, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03340-x (2024).

Chen, T. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of the tropical sea cucumber Stichopus monotuberculatus. Sci. Data. 11, 1245, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03985-8 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. The genome of an apodid holothuroid (Chiridota heheva) provides insights into its adaptation to a deep-sea reducing environment. Commun. Biol. 5, 224, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03176-4 (2022).

Ma, B. et al. Analysis of Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Bohadschia argus (Jaeger, 1833) (Aspidochirotida, Holothuriidae). Animals. 12, 1437, https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12111437 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. Gigascience. 7, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/gix120 (2017).

Wenger, A. M. et al. Accurate circular consensus long-read sequencing improves variant detection and assembly of a human genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 1155–1162, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0217-9 (2019).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 27, 764–770, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 (2011).

Vurture, G. W. et al. GenomeScope: fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics. 33, 2202–2204, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btx153 (2017).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods. 18, 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021).

Guan, D. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 36, 2896–2898, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa025 (2020).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 25, 1754–1760, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: An Integrated Tool for Comprehensive Microbial Variant Detection and Genome Assembly Improvement. PLoS. ONE. 9, e112963, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 (2014).

Krzywinski, M. et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome research. 19, 1639–1645, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.092759.109 (2009).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. PNSA. 117, 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Ou, S. et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol. 20, 275, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1905-y (2019).

Aylward, F. O. Introduction to Prokaryotic gene prediction (CDS and rRNA) V. 2. BMC Bioinformatics. 11, 1, https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.pjrdkm6 (2010).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: A Program for Improved Detection of Transfer RNA Genes in Genomic Sequence. Nucleic Acids Research. 25, 955–964, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.5.955 (1997).

Kalvari, I. et al. Rfam 13.0: shifting to a genome-centric resource for non-coding RNA families. Nucleic Acids Research. 46, D335–D342, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx1038 (2018).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics. 29, 2933–2935, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509 (2013).

Cantarel, B. L. et al. MAKER: An easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome research. 18, 188–196, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.6743907 (2008).

Kim, D. et al. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3122 (2015).

Brůna, T., Hoff, K. J., Lomsadze, A., Stanke, M. & Borodovsky, M. BRAKER2: automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP+ and AUGUSTUS supported by a protein database. NAR Genomics and Bioinformatics. 3, lqaa108, https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/lqaa108 (2021).

Mitchell, A. L. et al. InterPro in 2019: improving coverage, classification and access to protein sequence annotations. Nucleic Acids Research. 47, D351–D360, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1100 (2019).

The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Research. 45, D158–D169, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw1099 (2017).

Boutet, E. et al. UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, the Manually Annotated Section of the UniProt KnowledgeBase: How to Use the Entry View. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1374, 23–54, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-3167-5_2 (2016).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. Journal of molecular biology. 428, 726–731, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.006 (2016).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST plus: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 10, 421, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 (2009).

The Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Research. 47, D330–D338, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1055 (2019).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP586938 (2025).

Chen, T. Holothuria ocellata isolate DDF-2025, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBOCEH000000000 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33662152 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33662151 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35940911 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33662153 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33662154 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33662155 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33662156 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33662157 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33662158 (2025).

Fan, D. Genome sequence of sea cucumber Bohadschia ocellata (Holothuria ocellata). Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29124434.v1 (2025).

Fan, D. Genome sequence of sea cucumber Bohadschia ocellata (Holothuria ocellata). Baiduyun https://pan.baidu.com/s/10DBoB_GQQhThYBiloGInsA?pwd=wmhs (2025).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 21, 245, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was graciously supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (W2512089 to A.Y., and 42176132 and 32573487 to T.C.), the Research on breeding technology of candidate species for Guangdong modern marine ranching (2024-MRB-00-001 to T.C.), and the Guangdong Province Project (2024A1515011418 to T.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chunhua Ren, Chaoqun Hu, Ting Chen, and Aifen Yan planned and conceptualized the research. Qianying Huang, Xuan Wang, Zhou Qin, Hua Ge, Yingxin Lin, Junyan Wang, Yun Yang, Da Huo, Xiaoli Zhang and Xiangxing Zhu acquired and processed the samples. Zhou Qin and Dingding Fan constructed the genome and performed annotations. Qianying Huang, Xuan Wang, Zhou Qin and Dingding Fan analysed gene functions. Qianying Huang, Xuan Wang, Zhou Qin, Dingding Fan and Ting Chen conducted bioinformatic analyses. Zhenyu Xie, Chang Chen, Haipeng Qin, Dongsheng Tang, Chunhua Ren, Chaoqun Hu, Aifen Yan, and Ting Chen offered experimental materials and computational resources. Qianying Huang, Xuan Wang, Dingding Fan, Aifen Yan and Ting Chen composed the manuscript. Ting Chen and Aifen Yan and carried out revisions. All authors have reviewed and consented to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Q., Wang, X., Qin, Z. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of the tropical sea cucumber Bohadschia ocellate. Sci Data 13, 137 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06453-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06453-z