Abstract

The carrier transport characteristics of Sb2Se2Te topological insulators were investigated, after exposure to different levels of nitrogen gas. The magnetoresistance (MR) slope for the Sb2Se2Te crystal increased by approximately 100% at 10 K after 2-days of exposure. The Shubnikov-de Haas (SdH) oscillation amplitude increased by 30% while oscillation frequencies remained the same. MR slopes and the mobilities had the same dependency on temperature over a wide temperature range. All measured data conformed to a linear correlation between MR slope and mobility, supporting our hypothesis that the MR increase and the SdH oscillation enhancement might be caused by mobility enhancement induced by adsorbed N2 molecular.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological insulators (TIs) are characterized by their distinctive surface states with linear dispersion, and it exhibits remarkable helical spin texture1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The spin-momentum locking effect and various transport and optic characteristics of the surface states have been extensively investigated8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. To optimize the transport and optic characteristics of the surface state, the Fermi level tuning through back-gate voltage24, 25, material component adjustment25,26,27,28,29,30 are widely used. Various studies support that these fantastic characteristics are strongly related to the carrier mobility. Thus, as well as these complicating artificial techniques, an appropriate treatments to enhance the carrier mobility might be efficient way to optimize these carrier transport characteristics.

It is reported that the adsorbed molecules and/or extrinsic impurities and defects on TI surfaces might bend the band structure. The band bending near the surface of topological insulators may lead to a highly mobile two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG)31. This induced 2DEG will increase effective carrier mobility. This effect is experimentally observed in the Bi2Se3 topological insulator31. On the other hand, it was reported that nitrogen-doping enhanced the SdH oscillation amplitude in graphene and the amplitude enhancement increased when the nitrogen-doping rate was increased32. Theoretical studies have proposed that surface state carriers are robust against structural defects and extrinsic impurities because of their strong spin-orbit interaction1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Thus, it might be an appropriate way to enhance the carrier mobility through physical molecular adsorption on the surface of topological insulators. Many reports have focused on the influence of the surface chemical/physical interaction on TI in various kinds of gas environments through ARPES33 and XPS33,34,35. However, the similar effect on these transport characteristics of TI are still rare17, 36.

In this work, we experimentally perform the electrical transport characteristics in the Sb2Se2Te with different levels of N2 exposure. The results reveal that the non-saturating magnetoresistance (MR) ratio increased by approximately 100% at 10 K and the quantum Shubnikov-de Haas (SdH) oscillation amplitude increased by 30% after 2-days of exposure. The carrier scattering time and mobility increased by 30%. This results suggested that nitrogen-adsorbed on the surface may have optimized the carrier transport in the Sb2Se2Te topological insulators.

Experimental Methods

Single crystals of Sb2Se2Te were grown using a homemade resistance-heated floating zone furnace (RHFZ). The raw materials used to make the Sb2Se2Te crystals were mixed according to the stoichiometric ratio. At first, the stoichiometric mixtures of high purity elements Sb (99.995%), Se (99.995%) and Te (99.995%) was melted at 700~800 °C for 20 h and slowly cooled to room temperature in an evacuated quartz tube. The resultant material was then used as a feeding rod for the RHFZ experiment. Our previous work demonstrated that TI with extremely high uniformity can be obtained using the RHFZ method. After growth, the crystals were furnace cooled to room temperature. The as-grown crystals were cleaved along the basal plane, using a silvery reflective surface, and then prepared for the further experiments. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) confirmed that the crystals contained Sb:Se:Te = 2:2:1, and the XRD spectrum of the crystal was consistent with the Sb2Se2Te database.

The cleaved Sb2Se2Te single crystals were obtained using the Scotch-tape method. The thickness of the crystals was approximately 100 μm and their surface was approximately 6-mm × 5-mm. Gold wires were electrically attached to the cleaved crystal surface using a silver paste. Magnetotransport measurements were performed using the standard six-probe technique in a commercial apparatus (Quantum Design PPMS) with a magnetic field of up to 9 T. The magnetic field was applied perpendicular to the large cleaved surface.

Results and Discussion

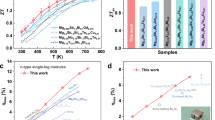

To determine the influence of the N2 exposure on the intrinsic transport characteristics, experiments were performed on the same sample under different levels of N2 exposure. Figure 1 illustrates the temperature dependence of the TI’s resistance for the newly cleaved crystal, the crystal after 6-months in a vacuum (N2 at 0.1 Torr), and the crystal subsequently exposed to N2 for 2-days at 1 atm. The measured temperature dependent resistances are similar for all three exposure levels with the only slight change at low temperatures. That implies that no chemical reaction but only physical molecular adsorption during the N2 exposure. Resistance decreased as temperature decreased, which is metallic behavior. The residual resistance ratio was approximately 5, which indicated that the sample was of superior quality and the N2 exposure did not substantially damage the quality of the sample. Residual resistance at low temperature is strongly related to sample defects and impurities. Figure 1 illustrates that larger residual resistance was detected in crystals exposed to N2 for longer duration. Thus, more N2 molecules were adsorbed on the Sb2Se2Te surface after extended N2 exposure.

The temperature dependent resistance of newly cleaved, 6-months in vacuum, 2-days N2 atmosphere exposed crystal. Metallic behavior was observed, and the residual resistance ratio was 5. Because resistances have the same temperature dependence. N2 exposure time does not obviously influence the overall characteristics of the TI.

Figure 2 illustrates the MR ratio (R(B) − R(B = 0))/R(B = 0), of the newly cleaved, 6-months in vacuum, and 2-days N2 exposure sample. Non-saturating MR was observed at all levels of N2 exposure, and no obvious saturation tendency was observed for magnetic fields of up to 9 T over a wide temperature ranges. Higher MR ratios were discovered at lower temperatures and longer N2 exposure times. The MR ratio increased from 0.55 for the newly cleaved sample to 0.7 for the sample exposed to N2 for 2 days at approximately 50 K and 9 T. Thus, N2 exposure enhanced the MR ratio.

Parish and Littlewood developed a classical random-resistor model (PL model) to explain the behavior of the linear MR37. It proposed that the linear MR originates from the mobility fluctuation in highly disordered or weakly disordered high-mobility materials. The local current density acquires spatial fluctuations in both magnitude and direction in an inhomogeneous carrier and mobility distribution. Therefore, it causes fluctuation in the Hall field that contributes to the linear MR, and this MR is determined by the mobility fluctuations rather than the mobility in weakly disordered conditions. Based on this PL model, the slope of the linear MR is proportional to the mobility in the weak mobility fluctuation region, Δμ/〈μ〉 < 1, where 〈μ〉 is the average mobility and Δμ is the mobility fluctuation level. The carrier mobility, μ, could be determined through the relation \(\mu =\frac{1}{neR}\), where n and e are the carrier concentration and carrier charge, respectively. The carrier concentration is determined from the Hall resistance.

Herein, we define the MR slope as the slope of linear MR extracted from fitting the linear MR at high magnetic fields. Figure 3 shows that the MR slope and μ had the same temperature dependence over a wide temperature range for different levels of N2 exposure. This shows excellent consistency with the prediction of the PL model in the weak mobility fluctuation region. The MR slope (mobility) increased from 0.06 (0.45 m 2/V · s) for the newly cleaved sample to 0.15 (0.9 m 2/V · s) for the 2-days N2 exposed sample at 10 K. Both the MR slope and mobility roughly doubled at 10 K after 2-days N2 exposure, which is consistent with the theoretical prediction that the MR is proportional to the mobility. Thus, all the observed MR slope changes may have been directly related to the mobility changes under the same condition in the weak mobility fluctuation region.

The MR slope and mobility, with the same temperature dependence, for different N2 exposure times. The MR slope and mobility had the same temperature dependence over a wide temperature range for different levels of N2 exposure. The MR slope and mobility increased approximately 100% after 2-days N2 exposure.

Figure 4 plots the MR slope of the measured data as a function of the mobilities for the same sample after different levels of N2 exposure at different temperatures. Linear correlation between MR slope and mobility was demonstrated over a wide mobility range (μ = 0.1–1.0 m2/V · s). N2 exposure induced spatial mobility disorder, led to carrier domination, and was a possible source of the decreased mobility observed. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the MR slope was proportional to the mobility, which supports the hypothesis that the enhanced linear MR ratio was caused by mobility enhancement.

Theoretical calculations proposed that extrinsic defects and impurities on the crystal surface might lead to electronic band bending, and downward band bending at the surface would induce a 2DEG. This effect was experimentally observed using ARPES in the Bi2Se3 TI with adsorbed N2 molecules on the surface. The induced 2DEG was formed at the surface and coexisted with the TI surface state shortly after the Bi2Se3 was exposed to N2 gas31. A 2DEG induced by extrinsic impurities contributed high-mobility carriers to the system and thus increased the effective mobility of the total carrier transport. Furthermore, following the PL model, the non-saturating linear MR originates from mobility fluctuations induced by the structural defects. This is consistent with the mobility-enhancement mechanism. Thus, the observed enhancement of the linear MR may have been caused by the physical molecular adsorption of N2 on the surface. The experimental report shows that the large non-saturating MR that is observed in the Sb2Se3 with extremely high carrier mobility that is induced by the molecular adsorption on the surface38.

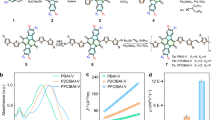

To further confirm the observed enhanced linear MR ratio originates from the enhance carrier mobility that is induced by 2DEG. The SdH oscillation, widely known to be dominated by 2D carriers, is studied. Figure 5 illustrates the magnetoresistances of Sb2Se2Te crystals newly cleaved and after two days of exposure to atmosphere. The inset displays the differential of the magnetoresistance, and clear SdH oscillations are revealed. Previous experimental studies have reported that SdH oscillations disappear after TIs are exposed to the atmosphere for several hours, but we discovered that the oscillation amplitude increased by 30% after two days of N2 exposure.

Figure 6(a,b) show ΔR(B) as a function of 1/B for the newly cleaved crystal and the crystal after two days of N2 exposure, respectively. The ΔR(B) was the measured R after subtracting the smooth polynomial background function. The oscillation amplitudes increased after N2 exposure and the oscillation amplitudes decreased as the temperature increased. The oscillation periods were equal for all measured temperatures. The oscillation frequencies were extracted from the Fourier transform, and a major peak at frequency of F = 186 T was observed for all measured temperatures [Fig. 6(c,d)]. The SdH oscillation frequency, F, is directly related to the Fermi-level cross section through the Onsager relation \(F=(\frac{\hslash c}{2e}){k}_{F}^{2}\), where k F is the Fermi vector, e is the electron charge and ħ is the Planck constant. From the observed SdH oscillation frequency, F = 187 T, k F = 7.5 × 106 cm−1 was calculated, which is consistent with the value (k F = 7.8 × 106 cm−1) obtained when ARPES was used on a different batches of the same Sb2Se2Te crystal.

The enhanced SdH oscillation amplitudes were reported in GaN/AlGaN 2DEG exposed to UV illumination. The enhanced oscillation amplitudes come from the increasing carrier due to the UV illumination39. The extracted carrier concentration increased by approximately 6% at 10 K after 2-days N2 exposure, which is an order of magnitude smaller than the total mobility change, implying that the carrier domination was not the predominant cause of the increased mobility observed in our work. On the other hand, the enhanced SdH oscillation amplitudes are also observed in a N-doped graphene, and larger oscillation amplitude was observed in a higher N-doped graphene. The oscillation frequency changes as the N-doped rate, that might come from the carrier doping that leads to the shift of the Fermi level. That is different from our observation that the oscillation frequencies are the same.

It is worthy to pay attention on that the SdH oscillation peaks slightly shift to higher magnetic fields. This indicates the shift of the Berry phase and the extracted Berry phase was 0.5 and 0.48, respectively. This effect is reported in the thin Bi nanoribbons with different levels of air exposure40. It is known that the Berry phase is 0.5 and 0 in systems with linear and parabolic E-K dispersions, respectively. This Berry phase shift might come from the combination of the TI surface state with linear E-K dispersion and the 2DEG with parabolic E-K dispersion. The coexistence of the topological state and a 2DEG on the surface was observed in Bi2Se3 31. These results all support the conclusion that the observed SdH oscillation originated from the surface states of the Sb2Se2Te.

The temperature dependence of SdH oscillation amplitudes is well described by Lifshitz-Kosevich theory, and can be expressed as

where \(\lambda (T/B)=\mathrm{(2}{\pi }^{2}{k}_{B}T{m}_{cyc})/(\hslash eB)\), and the Dingle temperature \({T}_{D}=\hslash \mathrm{/(2}\pi {k}_{B}\tau )\). Using Lifshitz-Kosevich theory, the effective characteristic parameters of the transport carriers in the surface states of the TI can be extracted. Figure 7 illustrates the normalized oscillation amplitude at B = 8.7 T as a function of temperature after the two exposure times, and the results fit the Lifshitz-Kosevich prediction. Fitting determined that \({m}_{cyc}=0.100\,{m}_{0}\) and 0.117 m 0 for the newly cleaved and two days exposed crystals, respectively, where m 0 is the free electron mass. using the linear dispersion relation, \({v}_{F}=\hslash {k}_{F}/{m}_{cyc}\), the Fermi velocity of the carriers on the surface states was determined as v F = 8.64 × 107 cm/s and v F = 7.40 × 107 cm/s for the newly cleaved and two days exposed crystal, respectively.

The Dingle factor, \({e}^{-\lambda ({T}_{D})}\), is canceled out in a fitting using the normalized amplitude. Therefore, the Dingle temperature was extracted from a plot of oscillation amplitude as a function of inverse magnetic field. The Dingle temperature is related to the surface carrier lifetime through the relation \({T}_{D}=\hslash /(2\pi {k}_{B}\tau )\). The carrier transport characteristics of the surface states, such as the mean free path, \({l}_{2D}={v}_{f}\tau \), and carrier mobility, \({\mu }_{2D}=(e{l}_{2D})/(\hslash {k}_{F})\), were systematically determined and are listed in Table 1. The carrier life time, the carrier mobility and the carrier mass increase after 2-days N2 exposure.

It comes to our attention that the SdH oscillation amplitude for the bismuth single crystals doped with a small amount of antimony is markedly enhanced with decreasing temperature41. It is proposed that the increasing electronic scattering time leads to the enhanced oscillation amplitudes. Our experimental results shows that the carrier scattering times increases after N2 exposure. That might be the intrinsic mechanism that leads to the enhanced mobility.

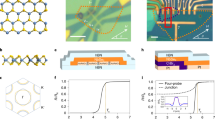

The surface states of TIs are theoretically tolerant to surface oxidation and scattering from structure defects and impurities due to spin-orbit interactions. However, all of previous experimental studies reported that surface oxidation suppressed carrier transport in the surface states. Surface oxidation was previously observed to smear out SdH oscillations after material was exposed to the atmosphere for several hours35, 42. Sb, Se, and Te are known to be oxidation activated, and to identify whether the oxidation and/or molecular adsorption occurred, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were performed. The XPS results in Fig. 8(a,b) clearly reveal slight oxidation on the surface, and that the oxidation peaks appeared after N2 exposure. The thickness of the oxidation layer, d, was estimated from I o /I m , where I o and I m are the intensity of the sample with and without surface oxidation, respectively.

λ, θ, ρ m , and ρ o are the mean electron escape depth, mean electron take off angle, atomic density of Te, and atomic density of TeO2, respectively34, 43. The estimated oxidation layer thickness was approximately 2.8 nm, consistent with its previously reported value34.

ARPES results have revealed that chemical oxidation and/or physical adsorption on the surface of TIs contributes to carrier doping and strongly shifts the Fermi level33, 40. As well as smearing out surface state transport behaviors, carrier doping limits the application potential of TIs. These are on-going problems and need to be solved before further application of these materials36, 44. Thus, the search for TI materials with surface states tolerant to oxidation, or techniques to prevent surface oxidation, is crucial. Our experimental result shows that the SdH oscillation frequencies of the Sb2Se2Te crystal were the same regardless of N2 exposure, which is consistent with theoretical predictions, and this resistance to surface oxidation is rarely experimentally reported for these materials. Furthermore, we found that atmosphere exposure enhanced SdH oscillation amplitudes and the carrier lift time, and the mobility increased by 30% after Sb2Se2Te surface oxidation.

Conclusion

The non-saturating MR was studied in the Sb2Se2Te TI after different levels of N2 exposure. The MR slopes and the mobilities had the same dependency on temperature over a wide temperature range, that is consistent with the PL model of weak mobility fluctuations. All measured data conformed to a linear correlation between MR slope and mobility over a wide mobility range. The MR slope increased by approximately 100% after 2-days of N2 exposure at 10 K. On the other hand, the SdH oscillation amplitude increased by 30%, and the oscillation frequencies remained the same after N2 exposure. The carrier scattering time and mobility increased by 30%. These carrier transport characteristics enhancement might have been caused by a high-mobility 2DEG induced by the nitrogen adsorbed on the surface. XPS revealed an oxidation layer of thickness 2.8 nm on the crystal’s surface. In addition to exhibiting oxidation-resistant carrier transport, our results suggested that the adsorbed N2 may have optimized the carrier transport of the surface states in our Sb2Se2Te TI.

References

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Leek, P. J. et al. Observation of Berry’s Phase in a Solid-State Qubit. Science 318, 1889–1892 (2007).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Superconducting Proximity Effect and Majorana Fermions at the Surface of a Topological Insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407-1–096407-4 (2008).

Wolf, S. A. et al. A Spin-Based Electronics Vision for the Future. Science 294, 1488–1495 (2001).

Hsieh, D. et al. A topological Dirac insulator in a quantum spin Hall phase. Nature 452, 970–974 (2008).

Hsieh, D. et al. Observation of Unconventional Quantum Spin Textures in Topological Insulators. Science 323, 919–922 (2009).

Li, C. H. et al. Electrical detection of charge-current-induced spin polarization due to spin-momentum locking in Bi2Se3. Nat. nanotechnol. 9, 218–224 (2014).

Ando, Y. et al. Electrical Detection of the Spin Polarization Due to Charge Flow in the Surface State of the Topological Insulator Bi1.5Sb0.5Te1.7Se1.3. Nano Lett. 14, 6226–6230 (2014).

Tang, J. S. et al. Electrical Detection of Spin-Polarized Surface States Conduction in (Bi0.53Sb0.47)2Te3 Topological Insulator. Nano Lett. 14, 5423–5429 (2014).

Mellnik, A. R. et al. Spin-transfer torque generated by a topological insulator. Nature 511, 449–451 (2014).

Deorati, P. et al. Observation of inverse spin Hall effect in bismuth selenide. Phys. Rev. B 90, 094403-1–094403-6 (2014).

Shiomi, Y. & Saitoh, E. et al. Spin-Electricity Conversion Induced by Spin Injection into Topological Insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 196601-1–196601-5 (2014).

Baker, A. A., Figueroa, A. I., Collins-McIntyre, L. J., van der Laan, G. & Hesjedala, T. Spin pumping in Ferromagnet-Topological Insulator-Ferromagnet Heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 5, 7907-1–7907-5 (2015).

Huang, S. M. et al. Extremely high-performance visible light photodetector in the Sb2SeTe2 nanoflake. Sci. Rep. 7, 45413-1–45413-7 (2017).

Yan, Y. et al. Synthesis and field emission properties of topological insulator Bi2Se3 nanoflake arrays. Nanotechnology 23, 305704-1–305704-5 (2012).

Yan, Y. et al. Effects of oxygen plasma etching on Sb2Te3 explored by torque detected quantum oscillations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 172407-1–172407-5 (2016).

Yan, Y. et al. Topological Surface State Enhanced Photothermoelectric Effect in Bi2Se3 Nanoribbons. Nano. Lett. 14, 4389–4394 (2014).

Yan, Y., Wang, L. X., Yu, D. P. & Liao, Z. M. Large Magnetoresistance in High Mobility Topological Insulator Bi2Se3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 033106-1–033106-4 (2013).

Yan, Y. et al. Synthesis and Quantum Transport Properties of Bi2Se3 Topological Insulator Nanostructures. Sci. Rep. 3, 1264-1–1264-5 (2013).

Yan, Y. et al. High-Mobility Bi2Se3 Nanoplates Manifesting Quantum Oscillations of Surface States in the Sidewalls. Sci. Rep. 4, 3817-1–3817-7 (2014).

Huang, S. M. et al. ShubnikovVde Haas oscillation of Bi2Te3 topological insulators with cm-scale uniformity. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 49, 255303-1–255303-5 (2016).

Huang, S. M., Yu, S. H. & Chou, M. The linear magnetoresistance from surface state of the Sb2SeTe2 topological insulator. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 245110-1–245110-4 (2016).

Lee, J. H., Park, J., Lee, J. H., Kim, J. S. & Lee, H. J. Gate-tuned differentiation of surface-conducting states in Bi1.5Sb0.5Te1.7Se1.3 topological-insulator thin crystals. Phys. Rev. B 86, 245321-1–245321-4 (2012).

Aulaev, A. et al. Electrically Tunable In-Plane Anisotropic Magnetoresistance in Topological Insulator BiSbTeSe2 Nanodevices. Nano Lett. 15, 2061–2066 (2015).

Hsiung, T. C., Mou, C. Y., Lee, T. K. & Chen, Y. Y. Surface-dominated transport and enhanced thermoelectric figure of merit in topological insulator Bi1.5Sb0.5Te1.7Se1.3. Nanoscale 7, 518–523 (2015).

Ren, Z., Taskin, A. A., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Large bulk resistivity and surface quantum oscillations in the topological insulator Bi2Te2Se. Phys. Rev. B 82, 241306-1–241306-4 (2010).

Taskin, A. A., Ren, Z., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Observation of Dirac Holes and Electrons in a Topological Insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 016801-1–016801-4 (2011).

Hong, S. S., Cha, JudyJ., Kong, D. & Cui, Y. Ultra-low carrier concentration and surface-dominant transport in antimonydoped Bi2Se3 topological insulator nanoribbons. Nat. Commun. 3, 757-1–757-7 (2012).

Arakane, T. et al. Tunable Dirac cone in the topological insulator Bi2−x Sb x Te3−y Sey. Nat. Commun. 3, 636-1–636-5 (2012).

Bianchi, M. et al. Coexistence of the topological state and a two-dimensional electron gas on the surface of Bi2Se3. Nat. Commun. 1, 128-1–128-5 (2010).

We, H. C. et al. Enhanced ShubnikovVDe Haas Oscillation in Nitrogen-Doped Graphene. ACS Nano. 9, 7207–7214 (2015).

Yashina, L. V. et al. Negligible Surface Reactivity of Topological Insulators Bi2Se3 and Bi2Te3 towards Oxygen and Water. ACS Nano 6, 5181–5191 (2013).

Bando, H. et al. Surface Oxidation of Bi2(Te, Se)3 Topological Insulators Depends on Cleavage Accuracy. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 12, 5607–5616 (2000).

Kong, D. et al. Rapid Surface Oxidation as a Source of Surface Degradation Factor for Bi2Se3. ACS Nano 5, 4698–4703 (2011).

Huang, S. M. et al. Observation of surface oxidation resistant Shubnikov-de Haas oscillations in Sb2SeTe2 topological insulator. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 054311-1–054311-4 (2017).

Parish, M. M. & Littlewood, P. B. Non-saturating magnetoresistance in heavily disordered semiconductors. Nature (London) 426, 162–165 (2003).

Huang, S. M., Yu, S. H. & Chou, M. Two-carrier transport-induced extremely large magnetoresistance in high mobility Sb2Se3. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 015107-1–015107-5 (2017).

Elhamri, S. et al. An electrical characterization of a two-dimensional electron gas in GaN/AlGaN on silicon substrates. J. Appl. Phys. 95, 7982-1–7982-4 (2004).

Ning, W. et al. Robust surface state transport in thin bismuth nanoribbons. Sci. Rep. 4, 7086–7091 (2014).

Satoh, N. & Takenake, H. Anomalous temperature dependence of the amplitude of longitudinal ShubnikovVde Haas oscillation. Physica B 403, 3705–3708 (2008).

Mele, E. J. & Balents, L. Topological invariants of time-reversal-invariant band structures. Phys. Rev. B 75, 121306-1–121306-4 (2007).

Strohmeier, B. R. An ESCA method for determining the oxide thickness on aluminum alloys. Surf Interface Anal. 15, 51–56 (1990).

Huang, S. M. et al. Thickness-dependent conductance in Sb2SeTe2 topological insulator nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 7, 1896-1–1896-7 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan through Grants No. NSC 103-2112-M-110-009-MY3 and NSYSU-KMU cooperation project No. 103-I 008 for SMH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.H. conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. S.J.H., C.H. and P.V.W. performance the experiment. Y.J.Y., S.H.Y. and M.C. grew the single crystal. All authors contributed to discusssion and reviewed the manuscrit.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, SM., Huang, SJ., Hsu, C. et al. Enhancement of carrier transport characteristic in the Sb2Se2Te topological insulators by N2 adsorption. Sci Rep 7, 5133 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05369-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05369-y

This article is cited by

-

The Singularity Paramagnetic Peak of Bi0.3Sb1.7Te3 with p-type Surface State

Nanoscale Research Letters (2022)

-

The quantum oscillations in different probe configurations in the \(\hbox {BiSbTe}_{{3}}\) topological insulator macroflake

Scientific Reports (2022)