Abstract

Ozone (O3) is a major air pollutant that has a profound effect on whole ecosystems. In this study we studied how hO3 affected the transmission of the Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus (TYLCCNV), a begomovirus, by the Q biotype Bemisia tabaci in a persistent, circulative manner. We found hO3 affected the transmission of TYLCCNV via the effect of it on the microbial community of the transmitting insect, such as Candidatus Hamiltonella, Ralstonia, Diaphorobacter, Caldilineaceae, Deinococcus, Rickettsia, Thysanophora penicillioides and Wallemia ichthyophaga. We concluded that hO3 decreased the resistance of acquiring virus tomatoes, and decreased the immune response and increased the endurance to extreme environments of viruliferous whiteflies by altering the composition and abundance of the microbial environments inside the body and on the surface of whitefly, as a result, it enhanced the TYLCV transmission rate by the Q biotype whitefly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global atmospheric concentration of ozone (O3) has risen from less than 10 ppb a century ago to 40–60 ppb at present, and it continues to increase at an annual rate of 1~2%1. In fact, in the forested regions of North America, the concentration of O3 reached 200 ppb in 19822, and the maximum atmospheric concentration in Beijing was 273–477 ppb in July 20003,4. O3, as a major air pollutant, affects some biological life on some organisms5. Ogawa et al. and Cui et al. found that O3-induced plants accumulated SA6,7. Salicylic acid (SA) plays a central role in the plant disease-resistance response, including the resistance against a broad spectrum of pathogens8. Deng et al. found that SA induced SAR to resist the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV)9. Sade et al. showed that SA was involved in tomato resistance to TYLCV8. Whether high O3 altered the transmission rate of plant virus by accumulating SA is unclear.

Ozone not only affects plant SA resistance, but also affects the composition and abundance of microbiology in the body and on the surface of insects10. And symbiotic microorganisms that act as an essential part of an insect’s structure and function have profound effects on the host insect’s biology11,12,13. When these microorganisms are removed or their composition is dramatically altered, the functions of the host insects demonstrate dysbiosis14. For example, germ-free Drosophila displayed delayed development, altered nutrient allocation and metabolic rates, and depressed gut immunity15,16,17. Some types of endosymbionts may regulate plant defenses. For example, the tomato psyllid, Bactericera cockerelli, reduced the expression of the tomato defensive pathway gene via the bacterial endosymbiont ‘Candidatus Liberibacter psyllaurous’18. Such changes maybe indirectly influence the transmission rate of a virus19. Moreover, endosymbionts can affect the transmission of a virus by means of direct participation. For example, Gottlieb et al. found that the endosymbiotic bacteria Hamiltonella from B biotype Bemisia tabaci in Israel produced the GroEL protein, which interacted with the TYLCV coat protein, thus enhancing the transmission efficiency of TYLCV20. Several studies have proved that endosymbiotic bacteria Rickettsia and Hamiltonella took part in TYLCCNV transmission via the Q biotype whitefly in China21,22,23,24. Zhu et al. demonstrated that a number of virulence-related genes were observed in the Rickettsia genome from Bemisia tabaci in Israel and China25. Moreover, fungi can directly assist the host in overcoming plant resistance; some fungi are associated with insects that can alter nitrogen directly from the insects to the plants and receive carbon (carbohydrates), in return, which can affect plant SA resistance, and some fungi can produce antibiotics that could affect a host insect’s immunity, which can indirectly affect the effectiveness of virus transmission26,27,28. Andrew & Lilleskov found that elevated CO2 (750 PPb) and O3 (80 PPb) affected the fungi community composition and sporocarp productivity29. Our previous study proved that high O3 (280 ± 20 PPb) significantly altered the abundance of microbes (bacteria and fungi) in the body and on the surface of the Q biotype whitefly10. Whether O3, as an environmental stress, alters the abundance and composition of the microbes associated with insects, and as a result, affects the transmission rate of plant virus by altering plant resistance, insect immunity, is unclear.

Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV), a devastating plant virus, has caused hundreds of millions of dollars of crop damage in America30. TYLCV includes Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus (TYLCSV), Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) and Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus (TYLCCNV), which were first identified in Italy, Israel and China, respectively31. TYLCCNV is predominantly found in China and is specifically transmitted by the Q biotype whitefly. Several studies provided that the Toll-like signaling of whitefly affected the TYLCV transmission rate23,32,33. Whether and how high O3 affect the transmission rate of TYLLCV is unclear.

To highlight the main effects of ozone and to exclude other environmental factors, we set our O3 treatment concentration at 280 ± 20 ppb (hO3). In this study, our hypothesis was that hO3 would alter TYLCCNV transmission by the Q biotype B. tabaci via affecting the resistance of the receptor plants, the changes in immunity and the microbial communities of the insect vectors. To test this hypothesis, we determined the effects of hO3 on the following characteristics of the Q biotype B. tabaci and tomato: (1) comparison of the TYLCCNV content between high O3 and control O3 on tomato after 48 h of transmitting the virus; (2) comparison of the expression of the gene associated with the SA signaling pathway of tomato and the expression of the gene associated with the Toll-like signaling pathway of viruliferous whiteflies; and (3) the community composition and abundance of the microbiota (bacteria and fungi) on the surface and inside of the body of viruliferous whiteflies.

Results

The Changes in Whitefly Transmission Efficiency

The transmission efficiency of TYLCCNV by whitefly was significantly enhanced by hO3, as indicated by the significant increase up to 2.87 times, (F1,104 = 6.872, P = 0.011) of the relative amount of virus in tomato leaves which were exposed to 20 pairs of viruliferous whiteflies(Fig. 1). However, more than a generation of fumigation exposure for whitefly (F 1,104 = 1.37, P = 0.279) and the interaction (F 1,104 = 2.416, P = 0.100) between these two factors did not significantly affect the transmission efficiency of TYLCCNV.

Relative Gene Expression of Tomato SA Resistance

The tomato SA resistance, as indicated by the relative amount of PAL and PR 1 in tomato leaves, were significantly affected by high O3 and viruliferous whiteflies, but was not affected by TYLCCNV alone. In fact, high O3 significantly increased the PAL expression level (49.32%) of healthy tomatoes (F 1,32 = 7.943, P = 0.0340), and high O3 significantly increased the PR 1 expression level of healthy tomatoes up to 6.43 times (F 1,32 = 13.073, P = 0.013). High O3 enhanced the PAL expression level (8.91%) of infected tomatoes by injection (F 1,32 = 0.524, P = 0.871), and high O3 enhanced the PR1 expression leve l (27.93%) of infected tomatoes by injection (F 1,32 = 1.388, P = 0.267) (Fig. 2A and B). The acquiring tomato SA resistance from viruliferous whiteflies, as indicated by the relative amount of PAL and PR 1 in tomato leaves, PAL was significantly affected by O3 concentration (F 1,104 = 14.412, P = 0.001), more than a generation of fumigation exposure for whitefly (F 1,104 = 19.115, P < 0.001), and the interaction between the two factors (F 1,104 = 14.024, P < 0.001). O3 concentration significantly increased the PAL expression level up to 1.38 times, but more than a generation of fumigation exposure of high O3 significantly decreased the PAL expression level to 33.71% (Fig. 2C). The relative amount of PR 1 in acquiring virus tomato leaves was high but was not affected by any one factor of O3 concentration (F 1, 104 = 0.617, P = 0.442), more than a generation of fumigation exposure of whitefly (F 1,104 = 0.287, P = 0.754), and the interaction (F 1, 104 = 1.696, P = 0.211) between these two factors (Fig. 2D).

The relative expression level of SA resistance genes. (A) is the PAL mRNA level from healthy tomatoes and infected tomatoes by injecting TYLCCNV under high O3 and control O3; (B) is the PR1 mRNA level from healthy tomatoes and infected tomatoes by injecting TYLCCNV under high O3 and control O3; (C) is the PAL mRNA level from acquiring TYLCCNV by whitefly; (D) is the PR1 mRNA level from acquiring TYLCCNV by whitefly. Black bar is for control O3, and red bar is for high O3, pink bar is for F0 generation, green bar is for F1 generation. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

Relative Gene Expression Associated with the Immunity of Viruliferous Whiteflies We found that high O3 significantly affected the expression of genes involved in immunity, as indicated by the relative amount of TRL 1 , TRL 7, defensin and lysozyme in viruliferous whiteflies. High O3 significantly decreased the expression of TRL 1 up to 25% (F 1,32 = 7.546, P = 0.035), the expression of TRL 7 up to 21% (F 1,32 = 7.396, P = 0.026), the expression of defensin up to 65.5% (F 1,32 = 13.876, P = 0.0019), and the expression of lysozyme up to 58.5% (F 1,32 = 9.636, P = 0.01) (Fig. 3). More than a generation of fumigation exposure of whitefly had similar effects with O3 concentration, but the data is not shown.

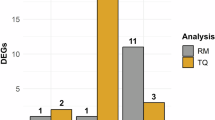

Significant Changes in the Abundances of the Bacterial and Fungal Communities

O3 concentration significantly affected the mean abundance of three bacteria on the surface of whitefly. High O3 significantly decreased the mean abundance of Rickettsia, increased the mean abundance of Ralstonia, and newly added Exiguobacterium (Fig. 4A). More than a generation of fumigation exposure of whitefly significantly affected seventeen bacteria on the surface. More than a generation of fumigation exposure of whitefly significantly decreased the mean abundance of Massilia and Ralstonia. In contrast, more than a generation of fumigation exposure of whitefly significantly enhanced the mean abundance of fifteen bacteria from 1.5–5times (Fig. 4B). The interaction between the O3 concentration and more than a generation of fumigation exposure for whitefly significantly affected three bacteria on the surface of whitefly. They were Ralstonia, Enterococcus and Exiguobacterium. The O3 concentration significantly affected the mean abundance of five bacteria in the body of whitefly. The O3 concentration significantly decreased the mean abundance of three bacteria that were Anaerolineaceae and OCS155_marine_group,and wiped out Caldilineaceae. At the same time, the O3 concentration significantly enhanced the mean abundance of Acinetobacter and KD4–96_norank (Fig. 4C). More than a generation of fumigation exposure of whitefly significantly affected five bacteria inside of body. More than a generation of fumigation exposure of whitefly significantly decreased the mean abundance of Enhydrobacter and wiped out Gordonia. At the same time, More than a generation of fumigation exposure of whitefly significantly enhanced the mean abundance of Bacteria_unclassified and new added two bacteria that was Citrobacter and Lysinibacillus (Fig. 4D). The interaction between the O3 concentration and more than a generation of fumigation exposure of viruliferous whitefly significantly affected four bacteria in the body of whitefly. They were Bacteria _unclassified, Citrobacter, Enhydrobacter and Lysinibacillus. The significant effects of O3 on the abundance of bacteria were shown in Table 1.

Comparing the differences of relative abundance of the bacteria. (A) is bacteria on the surface of whitefly from different O3 concentration, black bar is for control O3, and red bar is for high O3. (B) is bacteria on the surface of whitefly from different fumigated time, Black bar is bacteria from F0 generation whitefly that was for fumigated 48 h, and red bar is bacteria from F1 generation whitefly that was fumigated 48 h + 20d. (C) is bacteria inside the whitefly from different O3 concentration, black bar is for control O3, and red bar is for high O3. (D) is bacteria inside the whitefly from different fumigated time, black bar is from F0 generation whitefly that was for fumigated 48 h, and red bar is from F1 generation whitefly that was fumigated 48 h + 20 d. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

O3 concentration, more than a generation of fumigation exposure of viruliferous whitefly, and the interaction between the two factors significantly affected the same four fungi on the surface of whitefly that were Basidioascus magus, Lignincola laevis, Nectria parmeliae and Peziza quelepidotia; the significance level was similar (Fig. 5A and B). O3 concentration significantly enhanced the mean abundance of four fungi in the body of whitefly from 2.24 to 19.2 times. They were Diaporthe eres, Neurospora crassa, Thysanophora penicillioides and Wallemia ichthyophaga (Fig. 5C). More than a generation of fumigation exposure wiped out Candida tropicalis and added Diaporthe eres (Fig. 5D). The interaction between the two factors significantly affected the mean abundance of three fungi in the body of whitefly. They were Basidioascus magus, Diaporthe eres and Neurospora crassa. The significant effects of O3 on the abundance of fungi were shown in Table 2.

Comparing the differences of relative abundance of the fungi on the base of the mean value. (A) is fungi on the surface of whitefly from different O3 concentration, black bar is for control O3, and red bar is for high O3. (B) is fungi on the surface of whitefly from different fumigated time, black bar is fungi from F0 generation whitefly that was for fumigated 48 h, and red bar is fungi from F1 generation whitefly that was fumigated 48 h + 20d. (C) is fungi inside the whitefly from different O3 concentration, black bar is for control O3, and red bar is for high O3. (D) is fungi inside the whitefly from different fumigated time, black bar is from F0 generation whitefly that was for fumigated 48 h, and red bar is from F1 generation whitefly that was fumigated 48 h + 20d. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

Discussion

It is well known that host plant resistance can affect the transmission rates of viruses by vector insects. In addition, plant resistance is affected by various biotic and abiotic factors including atmospheric changes, herbivore insects and microorganisms. Our previous studies proved the elevated CO2 (750 ppb) and O3 (80 ppb) enhanced the resistance of tomato plants fumigated for 20–40 days by means of jasmonic acid defenses (JA) or salicylic acid defenses (SA) signaling pathways7,26. Zarate et al.34 found that whitefly-induced SA defenses suppressed the JA defenses of the host plant. Viruses can also affect host plant SA resistance and the virus transmission rate35,36. In the study, high O3 (≥280 ± 20ppb,48 h) as the sole abiotic factor significantly affect the resistance of healthy tomato plants, the results was same with early studies7,26. High O3 as an abiotic factor and whitefly and TYLCCNV as biotic factors affected the SA resistance of acquiring virus tomato plants, significantly up-regulating the PAL mRNA level of tomato plants, and the results were similar with a previous study that reported that 200 ppb O3 significantly enhanced the SA level of tobacco and Arabidopsis 37,38. However, O3 did not have a significant effect on the down-stream gene of SA (PR 1), which might be due to viruliferous whiteflies as the community of insects and the virus could overlap the effects on the mRNA of PR 1, making the mRNA of PR 1 of acquiring virus tomato plants reach big value under control O3. The results indicated that high O3 had a less direct effect on the SA resistance of receptor plants than viruliferous whiteflies did. Viruliferous whiteflies with TYLCCNV should have same effects on the SA resistance of receptor plants under the same O3 concentration. Why did the F0 generation (O3 fumigation for 48 h) of viruliferous whitefly significantly up-regulate the PAL mRNA level of the receptor plants, but the F1 generation (O3 fumigation for 20d + 48 h) of viruliferous whitefly significantly down-regulate the PAL mRNA level of the receptor plants under same O3 concentration? We thought that high O3 altered the SA resistance of the receptor plants by regulating the composition and abundance of the microbia associated with whiteflies. In fact, some insect symbiotic microorganisms may have influenced the SA defense of the receptor plants12,18. In the study, the O3 concentration significantly increased the abundance of Ralstonia, and prolonged O3 fumigation exposure time significantly decreased the abundance of Ralstonia on the surface of the whitefly. Similarly, the O3 concentration and the O3 fumigation exposure time had contrary effects on the abundance of four fungi (Basidioascus magus, Lignincola laevis, Nectria parmeliae and Peziza quelepidotia) on the surface of whitefly. Because the change trends of the abundances of Ralstonia, Basidioascus magus, Lignincola laevis, Nectria parmeliae and Peziza quelepidotia agreed with that of the PAL mRNA levels between O3 concentration and O3 fumigation exposure time, we speculated that Ralstonia, Basidioascus magus, Lignincola laevis, Nectria parmeliae and Peziza quelepidotia might play major roles in ozone-regulated receptor plant resistance. Studies showed that Ralstonia could degrade phenol and Nectria parmeliae could produce cell wall-degrading enzymes39,40. Such research might explain why O3 fumigation exposure time and O3 concentration had different effects on the SA defense of acquiring virus tomatoes. However, it is necessary for us to further confirm the functions of Basidioascus magus, Lignincola laevis, Nectria parmeliae and Peziza quelepidotia on SA resistance in plants in the future.

Sade et al.8 found SA was involved in tomato resistance to Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus (TYLCV), and the TYLCV transmission rate by whiteflies was negatively correlated with the SA resistance of the receptor plants. That is, the higher the resistance, the lower the transmission rate of TYLCV by whiteflies41. However, in the study, the resistance of tomato plants increased under high O3, and at the same time, the transmission rate of TYLCV by whiteflies increased under high O3. What brought about the contradictory results? The transmission rate of TYLCV was not only affected by the resistance of the receptor plants but was also affected by symbiotic microorganisms associated with the vector insects. Some insect symbiotic microorganisms may influence the transmission of a virus by regulating the SA or JA defenses of the receptor plants12,18; some insect symbiotic microorganisms may work via the secretion of a capsid protein to help transmit the plant virus20. Studies have shown that Ralstonia and Diaphorobacter could degrade phenol and decrease plant SA resistance39,42, Basidioascus could resist environmental stress43, Lignincola laves and Wallemia ichthyophaga can resist hypersaline44, Nectria parmeliae could produce cell wall-degrading enzymes and decrease the plant resistance45, Diaporthe eres can degrade 3-nitrotoluene46, and Thysanophora penicillioides can affect whitefly immunity10. The changes in composition or abundance of these bacteria and fungi could affect plant and insect resistance to stress, which could change the transmission virus rate by the vector insects. In the study, high O3 significantly increased the abundance of Ralstonia, Diaphorobacter and Nectria parmeliae on the surface of whitefly, while decreasing the acquired TYLCCNV tomato resistance and increasing the TYLCCNV transmission rate by whitefly. High O3 significantly increased the abundance of Basidioascus, Wallemia ichthyophaga, Diaporthe eres and Thysanophora penicillioides, thus enhancing whitefly fittness under high O3 and increasing the TYLCCNV transmission rate by whitefly.

Moreover, high O3 fumigation for 48 h only significantly decreased the abundance of Rickettsia on the surface of whitefly and significantly enhanced the abundance of Hamiltonella in the body of whitefly. The results proved the points of view that Rickettsia and Hamiltonella affected the TYLCV transmission rate20,21,23,25. In the study, Rickettsia showed a positive with the immunity of whitefly, the result was agreed with our previously study10. Early study showed Rickettsia was a positive with TYLCV transmission rate21. However, in the study, Rickettsia showed a negative transmission TYLCV rate, that is, high O3 significantly decreased the abundance of Rickettsia and significantly increased the TYLCV transmission rate. We thought that high O3 decreased the immunity of whitefly, as a result, indirectly promoted the TYLCV transmission. And same symbiotic bacteria had different biological effect in different hosts. In the study, high O3 enhanced the abundance of catalase positive bacteria; for example, Ralstonia and Exiguobacterium were enhanced on the surface of whitefly, and Acinetobacter and KD4–96_norank were enhanced in the body of whitefly. In addition, the prolonged O3 fumigation exposure time enhanced the abundance of more catalase positive bacteria. For instance, the prolonged O3 fumigation exposure time significantly enhanced the abundance of nine catalase positive bacteria on the surface and three catalase positive bacteria in the body of whitefly. They were Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Micrococcus, Escherichia – Shigella, Curtobacterium, Cloacibacterium, Actinomycetaceae, Ralstonia, Exiguobacterium, Citrobacter, Enhydrobacter, and Lysinibacillus. The results demonstrated that O3 made organisms generate a lot of hydrogen peroxide. This might partly explain why O3 fumigation exposure time and O3 concentration had different effects on the TYLCCNV transmission rate. In the future, we could validate the special function of the TYLCCNV transmission rate of bacteria and fungi that demonstrated significant differences under high O3 and long O3 fumigation exposure time.

Materials and Methods

O3 Treatment

In the hO3 treatment, O3 was generated from ambient air with an O3 generator (3S-A10, Beijing Ligong University, Beijing, China) and then transported into an artificial climate chamber at 25 ± 1 °C, 70% RH and a 14:10 L:D photoperiod (PRX-450C, Ningbo, China). The O3 concentrations were monitored in real time (Shenzhen Yiyuntian Electronic CO. LTD). In the treatment, O3 was ventilated from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m, and an artificial climate chamber at 25 ± 1 °C, 70% RH and a 14:10 L: D photoperiod (PRX-450C, Ningbo, China) without an O3 generator was used as a control. In the study, we used four chambers for high O3 treatment and four chambers for control treatment, three high O3 arrangements and three control arrangements were used to cultivate plant, the other two arrangements were used to train viruliferous whiteflies.

Healthy Plants, Whiteflies and TYLCCNV bacterial liquid

Tomato seeds were sown in 10 cm diameter plastic pots with commercial peat soil, and the pots was incubated in a screened cage (60 × 40 × 40 cm, 100 mesh) in a greenhouse. The plants were watered every two days. To conduct detoxification treatment, Q-biotype B. tabaci fed on an 80 cm-high cotton plant in a screened cage (150 × 100 × 100 cm, 100 mesh) in a greenhouse. The Q-biotype B. tabaci and TYLCCNV bacterial liquid were obtained from the Institute of Vegetables and Flowers of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS) on April 22, 2015, and they were identified by PCR. TYLCCNV bacterial liquid means Agrobacterium tumefaciens carrying TYLCCNV and betasatellite DNAβ. Agroinfiltration was performed with an overnight culture as described previously47,48.

High O3 Fumigation for Infected and Healthy Tomato Plants

A week after injecting TYLCCNV bacterial liquid, eighteen infected tomato plants and eighteen healthy tomato plants confirmed by PCR were transferred to three high O3 (280 ± 20 ppb, hO3) arrangements and three control O3 (50 ± 10 ppb) arrangements (six infected tomato plants and six healthy tomato plants in each arrangement), respectively. After 48 h, 1–2 new leaves were collected from the infected and healthy tomato plants. To determine whether the SA resistance of the tomato plants came from high O3 or from TYLCCNV alone, we determined the mRNA levels of the genes of phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) and pathogenesis related protein1 (PR 1) from the infected or healthy tomatoes leaves using real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) as described in the next section. The experiment was repeated three times.

Viruliferous Plants and Viruliferous Insects

First, 200 μl bacterial liquid with TYLCCNV DNA was injected to 24 healthy tomato plants at the three-true-leaf stage and were incubated in a screened cage (60 × 40 × 40 cm, 100 mesh) in a greenhouse. Infected plants were confirmed by the appearance of typical leaf curl symptoms and PCR. Approximately 1000 pairs of newly eclosed whitefly adults were released onto 6 viruliferous plants 20 days after injection. Then, 3 viruliferous plants with whiteflies were transferred to a high O3 (280 ± 20 ppb, hO3) arrangement, and 3 viruliferous plants with whiteflies were transferred to a control O3 (50 ± 10 ppb, control O3) arrangement.

Transmission of TYLCCNV by Whiteflies

Twenty pairs of randomly selected viruliferous Q-biotype B. tabaci were transferred to healthy tomato leaves covered with bags (40 × 50 cm, 100 mesh). Six healthy tomato plants (three bags/plant) with viruliferous Q-biotype B. tabaci were transferred to the hO3 and control O3 arrangements. After 48 h, the bag with acquiring virus tomato leaves and the transmitting virus whiteflies from each plant was collected, and the experiment was repeated three times. All live whiteflies from a plant (3 bags) were used to extract the total RNA of the whitefly and the DNA of the microbial community on the surface and in the body of the whitefly, as described in the next section. The RNA of the whitefly was used to assess the relative gene (Toll-like receptor 1 (TLR 1 ), Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR 7), defensin and lysozyme) expressions in the toll pathway. At the same time, the RNA and DNA in the leaves from a bag were extracted, and the relative gene expression of SA resistance and the TYLCCNV DNA by qRT-PCR and q-PCR were assessed as described in the following section.

Relative Gene Expression Associated with SA Resistance in Tomato and the Toll Pathway of Whitefly and TVLCCNV DNA by qRT-PCR and q-PCR

To explore whether hO3 affected TYLCCNV transmission by whiteflies, we compared the TYLCCNV DNA of the acquiring virus tomato leaves from hO3 and the control O3 using real-time quantitative PCR (q-PCR). DNA was extracted from the leaves with a plant genomic DNA kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, Co., Ltd). To explore whether the SA resistance of tomatoes result from hO3 or TYLCCNV alone, we determined the mRNA levels of the PAL and PR 1 genes from healthy and infected tomatoes from hO3 and the control O3 using real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Moreover, in order to determine whether the resistance and acquiring virus effects of the receptor plants were mainly affected by the direct effect of hO3 or the indirect effect of hO3 via affecting microbes associated with whitefly, we compared the TYLCCNV DNA and the mRNA levels of the SA signaling pathway of acquiring virus tomatoes transmitted by viruliferous Q-biotype B. tabaci that were fumigated for 48 h (F0 generation) and were fumigated for 48 h + 20 days (F1 generation). To explore whether changes in gene expression altered viruliferous whitefly immunity under hO3, we determined the mRNA levels of the toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1) and the toll-like receptor 7 genes (TLR7), defensin and lysozyme (LYS) by real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). The total RNA of the live viruliferous whitefly samples and the total RNA of acquiring virus tomato leaves from the high O3 treatment and the control O3 were extracted by TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The RT-qPCR reaction conditions were previously described10 by Hong et al.10. Twenty-seven biological replicates with three technical replicates from high O3 and control O3 were performed in a generation. The relative quantification was performed using the Livak method (2−△△C T), and the values obtained were normalized to the housekeeping genes.

The Composition and Abundance of the Microbial Communities

To explore whether changes in the microbial communities altered TYLCCNV transmission by whitefly under hO3, we determined the composition and abundance of the bacterial and fungal communities on the surface and the inside of the body of the whiteflies from the hO3 treatment (280 ± 20 ppb) and the control (50 ± 10 ppb) using 16S and 18S sequencing, which were conducted according to previously described10. Because the total microbial DNA on the surface of whitefly was very low, about 60% live whiteflies from acquiring virus tomatoes were used as a microbial sample (bacteria and fungus). In a generation, nine microbial samples from the treatment and control were used to analyze the composition and abundance of the bacterial and fungal communities on the surface and inside the body of the whiteflies from the hO3 treatment and the control O3. In all, thirty-six microbial samples were analyzed.

Statistical Analyses

Multivariate analysis under the general linear model was used to analyze the hO3 effects on the content of TYLCCNV, gene expression, and the relative abundance of the microbial community; the level of significance was set at P < 0.05. The fitting agenda was based on the mean of the corresponding element. The statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 19.0 (IBM, USA).

References

IPCC. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge (2013).

Kress, Lw, Skelly, J. M. & Hinkelmann, K. H. Relative sensitiviy of 28 full-sib families of Pinus taeda to O3. Can. J. For. Res. 12(2), 203–209 (1982).

Wang, S. L. & Cai, F. H. Provincial characteristics of ozone pollution in beijing. Sciientia geographica sinica. 22(3), 360–364 (2002).

An, J. L., Wang, Y. S., Li, X., Sun, Y. & Shen, S. H. et al. Analysis of the relationship between NO, NO2 and O3 concentrations in Beijing. Huan Jing Ke Xue. 28, 706–711 (2007).

Mokoena, M. L., Brink, C. B., Harvey, B. H. & Oliver, D. W. Appraisal of ozone as biologically active molecule and experimental tool in biomedical sciences. Med Chem Res 20(9), 1687–1695 (2011).

Ogawa, D., Nakajima, N., Tamaoki, M., Aono, M. & Kubo, A. et al. The isochorismate pathway is negatively regulated by salicylic acid signaling in O3-exposed Arabidopsis. Planta. 226(5), 1277–1285 (2007).

Cui, H. Y., Sun, Y. C., Su, J. W., Ren, Q. & Li, C. Y. et al. Elevated O3 reduces the fitness of Bemisia tabaci via enhancement of the SA dependent defense of the tomato plant. Arthropod-Plant Int. 6, 425–437 (2012).

Sade, D., Sade, N., Shriki, O., Lerner, S. & Gebremedhin, A. et al. Water balance, hormone homeostasis, and sugar signaling are all involved in tomato resistance to Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus. Plant Physiol. 165, 1684–1697 (2014).

Deng, C. H., Zhang, X. M., Zhu, W. M. & Qian, J. Investigation of tomato plant defence response to Tobacco Mosaic Virus by determination of Methyl Salicylate with SPME-Capillary GC-MS. Chromatographia. 59(3), 263–268 (2004).

Hong, Y. Y., Yi, T. Y., Tan, X. L., Zhao, Z. H. & Ge, F. High Ozone (O3) Affects the fitness associated with the microbial composition and abundance of Q biotype Bemisia tabaci. Front Microbiol. 7, 1593, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.01593 (2016).

Dale, C. & Moran, N. A. Molecular interactions between bacterial symbionts and their hosts. Cell. 126(3), 453–65 (2006).

Frago, E., Dicke, M. & Godfray, H. C. J. Insect symbionts as hidden players in insect–plant interactions. Trends Ecol Evol. 27, 705–711 (2012).

Bing, X. L., Yang, J., Zchori-Fein, E., Wang, X. W. & Liu, S. S. Characterization of a newly discovered symbiont of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Appl Environ Microb. 79, 569–575 (2013).

Stecher, B., Maier, L. & Hardt, W. D. Blooming’ in the gut: how dysbiosis might contribute to pathogen evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 11(4), 277–84 (2013).

Ridley, E. V., Wong, A. C., Westmiller, S. & Douglas, A. E. Impact of the resident microbiota on the nutritional phenotype of Drosophila melanogaster. Plos One. 7(5), 6911–6916 (2012).

Ryu, J. H., Kim, S. H., Lee, H. Y., Bai, J. Y. & Nam, Y. D. et al. Innate immune homeostasis by thehomeobox gene caudal and commensal-gut mutualism in Drosophila. Science. 319, 777–82 (2008).

Storelli, G., Defaye, A., Erkosar, B., Hols, P. & Royet, J. et al. Lactobacillus plantarum promotes Drosophila systemic growth by modulating hormonal signals through TOR-dependent nutrient sensing. Cell Metab. 14(3), 403–14 (2011).

Casteel, C. L., Hansen, A. K., Walling, L. L. & Paine, T. D. Manipulation of plant defense responses by the Tomato Psyllid (Bactericerca cockerelli) and its associated endosymbiont Candidatus Liberibacter Psyllaurous. PLoS One. 7(4), e35191, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035191 (2012).

Gutiérrez, S., Michalakis, Y., Munster, M. & Blanc, S. Plant feeding by insect vectors can affect life cycle, population genetics and evolution of plant viruses. Funct Ecol. 27, 610–622 (2013).

Gottlieb, Y., Zchori-Fein, E., Mozes-Daube, N., Kontsedalov, S. & Skaljac, M. et al. The transmission efficiency of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus by the whitefly Bemisia tabaci is correlated with the presence of a specific symbiotic bacterium species. J Virol. 84, 9310–9317 (2010).

Li, J. M., Ruan, Y. M., Li, F. F., Liu, S. S. & Wang, X. W. Gene expression profiling of the whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) Middle East – Asia Minor 1 feeding on healthy and Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus-infected tobacco. Insect Sci. 18, 11–22 (2011).

Luan, J. B., Wang, X. W., Colvin, J. & Liu, S. S. Plant-mediated whitefly–begomovirus interactions: research progress and future prospects. B Entom Res. 104, 267–276 (2014).

Luan, J. B., Li., J. M., Varela, N. L., Wang, Y. L. & Li, F. F. et al. Global analysis of the transcriptional response of whitefly to Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl China Virus reveals the relationship of coevolved adaptations. J Virol. 85(7), 3330–3340 (2011).

Su, Q., Pan, H., Liu, B., Chu, D. & Xie, W. et al. Insect symbiont facilitates vector acquisition, retention and transmission of plant virus. Sci Rep. 3, 1367 (2013).

Zhu, D. T., Xia, W. Q., Rao, Q., Liu, S. S. & Ghanim, M. et al. Sequencing and comparison of the Rickettsia genomes from the whitefly Bemisia tabaci Middle East Asia Minor. Insect Sci. 23(4), 531–542 (2016).

Guo, H. J., Sun, Y. C., Ren, Q., Zhu-Salzman, K. & Kang, L. et al. Elevated CO2 reduces the resistance and tolerance of tomato plants to helicoverpa armigera by suppressing the JA signaling Pathway. PloS One. 7(7), e41426, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.004142 (2012).

Behie, S. W., Zelisko, P. M. & Bidochka, M. J. Endophytic insect-parasitic fungi translocate nitrogen directly from insects to plants. Science. 336, 1576–1577 (2012).

Behie, S. W. & Bidochka, M. J. An additional branch of the soil nitrogen cycle: Ubiquity of insect-derived nitrogen transfer to plants by endophytic insect pathogenic fungi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 80, 1553–1560 (2013).

Andrew, C. & Lilleskov, E. A. Productivity and community structure of ectomycorrhizal fungal sporocarps under increased atmospheric CO2 and O3. Ecol Lett. 12, 813–822 (2009).

Cass, B. N., Yallouz, R., Bondy, E. C., Mozes-Daube, N. & Horowitz, R. et al. Dynamics of the endosymbiont Rickettsia in an insect pest. Microb Ecol. 70, 1–11 (2015).

Wu, J. B., Dai, F. M. & Zhou, X. P. First report of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus in China. Ann. Appl. Biol. 155, 439–448 (2006).

Bao, Y. Y., Qu, L. Y., Zhao, D., Chen, L. B. & Jin, H. Y. et al. The genome- and transcriptome-wide analysis of innate immunity in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. BMC Genomics. 14, 160 (2013).

Pakkianathan, B. C., Kontsedalov, S., Lebedev, G., Mahadav, A. & Zeidan, M. et al. Replication of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus in its whitefly vector, Bemisia tabaci. J Virol. 89, 9791–9803 (2015).

Zarate, S. I., Kempema, L. A. & Walling, L. L. Silverleaf whitefly induces Salicylic Acid defenses and suppresses effectual Jasmonic Acid defenses. Plant Physiol. 143, 866–875 (2007).

Ziebell, H., Murphy, A. M., Groen, S. C., Tungadi, T. & Westwood, J. H. et al. Cucumber mosaic virus and its 2b RNA silencing suppressor modify plant-aphid interactions in tobacco. Sci Rep. 1, 187 (2012).

Stafford, C. A., Walker, G. P. & Ullman, D. E. Hitching a ride: vector feeding and virus transmission. Communicative & Integrative Biology. 5(1), 43–49 (2012).

Ogawa, D., Nakajima, N., Sano, T., Tamaoki, M. & Aono, M. et al. Regulation of salicylic acid synthesis in ozone-exposed tobacco and Arabidopsis. Phyton. 45, 169–175 (2005).

Ogawa, D., Nakajima, N., Seo, S., Mitsuhara, I. & Kamada, H. et al. The phenylalanine pathway is the main route of salicylic acid biosynthesis in tobacco mosaic virus -infected tobacco leaves. Plant Biotechnol. 23, 395–398 (2006).

Liu, Z. P., Yang, H. F. & Zhou, P. J. Studies on the metabolism pathway of aniline degradation by Comamonas Acidovorans AN3. Acta Microbiologica Sinica. 39(5), 448–453 (1999).

Lawrey, J. D. Chemical Interactions Between Two Lichen-degrading Fungi. Chem Ecol. 26, 1821–1831 (2000).

Lapidot, M., Friedmann, M., Pilowsky, M., Ben-Joseph, R. & Cohen, S. Effect of host plant resistance to Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus (TYLCV) on virus acquisition and transmission by its whitefly Vector. J virol. 91(12), 1209–1213 (2001).

Zhang, T., Ren, H. F., Liu, Y., Zhu, B. L. & Liu, Z. P. A novel degradation pathway of chloroaniline in diaphorobacter, sp. pca039 entails initial hydroxylation. J Microb Biotech. 26(4), 665–673 (2010).

Arora, P. K. Bacterial degradation of monocyclic aromatic amines. Front Microbiol. 6, 820 (2015).

Nguyen, H. D. T., Chabot, D., Hirooka, Y., Roberson, R. W. & Seifert, K. A. Basidioascus undulatus genome, origins, and sexuality. Imafungus. 6(1), 215–231 (2015).

Pang, K. L., Vrijmoed, L. L. P. & Jones, E. B. C. Genetic variation within the cosmopolitan aquatic fungus Lignincola laves (Microascales Ascomycota). Org Divers Evol. 13, 301–309 (2013).

Singh, D., Kumari, A. & Ramanathan, G. 3-Nitrotoluene dioxygenase from Diaphorobacter sp. strains: cloning, sequencing and evolutionary studies. Biodegradation. 25(4), 479–492 (2014).

Cui, X., Tao, X., Xie, Y., Fauquet, C. M. & Zhou, X. A DNAb associated with Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus is required for symptom induction. J. Virol. 78, 13966–13974 (2004).

Yang, J. Y. et al. betaC1, the pathogenicity factor of TYLCCNV, interacts with AS1 to alter leaf development and suppress selective jasmonic acid responses. Genes Dev. 22, 2564–2577 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank LinYu Sui from the Hunan Agricultural University for her assistance in experiment, and we thanks Yuchen Sun, Huijuan Guo and Xianghui Liu from State Key Laboratory of Integrated Management of Pest Insects and Rodents, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences for their suggestion and assistance in experiment. This project was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB11050400), the National Natural Science Fundation of China (No. 31370438) and Agro-Industry R and D Special Fund of China (Agriculture 201303019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.G. and Y.Y.H. designed the experiment. Y.Y.H. performed the experiment and wrote the paper. T.Y.Y. and X.L.T. analyzed data, J.W.S. took part in revising the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, Y., Yi, T., Tan, X. et al. Microbes affected the TYLCCNV transmission rate by the Q biotype whitefly under high O3 . Sci Rep 7, 14412 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14023-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14023-6

This article is cited by

-

Whitefly endosymbionts: IPM opportunity or tilting at windmills?

Journal of Pest Science (2022)