Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between eating behavior and poor glycemic control in 5,479 Japanese adults with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) <6.5% who participated in health checks. Respondents to a 2013 baseline survey of eating behavior, including skipping breakfast and how quickly they consumed food were followed up until 2017. We defined poor glycemic control after follow-up as HbA1c ≥6.5%, or increases in HbA1c of ≥0.5% and/or being under medication to control diabetes. We identified 109 (2.0%) respondents who met these criteria for poor glycemic control. After adjusting for sex, age, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), and eating behavior, the risk of poor glycemic control was increased in males (odds ratio [OR], 2.38; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.37–4.12; p < 0.01), and associated with being older (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04–1.11; p < 0.001), having a higher BMI (OR, 1.29; 95% CI 1.23–1.35; p < 0.001), skipping breakfast ≥3 times/week (OR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.35–4.41; p < 0.01), and changing from eating slowly or at medium speed to eating quickly (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.04–4.26; p < 0.05). In conclusion, Japanese adults who were male, older, had a high BMI, skipped breakfast ≥3 times/week and ate quickly were at increased risk for poor glycemic control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is characterized by chronic hyperglycemia and is closely associated with many serious health issues, including neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy1. The global prevalence of type 2 diabetes has increased from 8.1% to 9.6% in Asians and from 6.0% to 7.9% in Caucasians2. The reported incidence of type 2 diabetes in Japan increased from 6.9 to 10 per million between 1997 and 20163. Because diabetes and its associated complications comprise a major health concern, the Japanese government has continuously strived to establish a national policy to prevent diabetes.

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reflects glycemic status over time and thus serves as a biomarker for testing and monitoring diabetes4. It can be applied to guide strategies for treating and controlling diabetes and to predict the risk of progressive complications of diabetes5. Therefore, monitoring HbA1c is important for developing appropriate strategies to prevent diabetes and its associated complications.

Eating behavior, such as skipping breakfast and rapidly consuming food, are lifestyle factors that could contribute to an increased risk of diabetes. For instance, a meta-analysis found a pooled adjusted relative risk between skipping breakfast and type 2 diabetes of 1.21 (95% CI, 1.05–1.24)6. In addition, a case control study associated a higher risk of diabetes with rapid, rather than slow food consumption7. A cross-sectional study also associated hyperglycemia in the general population with late-night food consumption8. These findings indicated that eating behavior is associated with risk of diabetes. However, clinical studies are required because evidence of risk for poor glycemic control is limited.

The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare has recommended specific health checks that focus on metabolic syndrome for individuals aged 40–74 years. Medical insurers systematically implement regular health checks, survey eating behavior and measure HbAlc levels. Therefore, the research on Japanese adults was convenient to collect information on eating behavior and HbA1c level. The present study tested the hypothesis that eating behavior is associated with a significantly increased risk of poor glycemic control in a Japanese population who underwent regular health checks.

Results

The baseline prevalence of skipping breakfast ≥3 times/week and rapid food consumption were 9.7% and 41.5%, respectively (Table 1). Study participants who skipped breakfast ≥3 times/week were significantly more likely to be male, older, exercise less frequently, have a higher body mass index (BMI), higher HbA1c values, a higher frequency of dinner within two hours of bedtime, a higher frequency of eating snacks after dinner and consume more alcohol, than those who did not (p < 0.05 for all). Compared with participants that did not eat quickly, those who did were significantly more likely to be male, have higher Brinkman indexes, higher BMI, higher HbA1c, slower walking speed, and higher frequencies of consuming dinner within two hours of bedtime, and of eating snacks after dinner (p < 0.05 for all).

Ninety (1.6%) of the participants had HbA1c ≥6.5% and 173 (31.6%) had increases in HbA1c of ≥0.5% (Table 2). Among the latter, 46.2% had HbA1c ≥6.5%. The number of participants with diabetes under control with medication was 47 (0.9%). Thus, 109 (2.0%) participants had poor glycemic control at the time of follow up.

The results of univariate logistic regression analyses showed that odds ratios (OR) for having poor glycemic control were higher for males, older persons, and those with a higher Brinkman index than participants who did not have these factors (p < 0.001 for all) (Table 3). ORs for having poor glycemic control were higher when breakfast was skipped ≥3, compared with <3 times/week between baseline and at four years later (OR, 2.57; p < 0.01). ORs for having poor glycemic control were increased among those who did not eat quickly at baseline but ate quickly four years later (OR, 2.36; p < 0.05) and who ate quickly at baseline and after four years (OR, 2.46; p < 0.001). ORs for having poor glycemic control were also higher for consuming snacks after dinner ≥3 times/week at baseline, and eating snacks <3 times/week after four years compared with eating snacks after dinner <3 times/week at baseline and after four years (OR, 1.79; p < 0.05).

The risk of having poor glycemic control was increased in males (OR, 2.38; p < 0.01), older persons (OR, 1.07; p < 0.001) and those who skipped breakfast ≥3 times/week at baseline and after four years vs. <3 times/week at baseline and after four years vs. (OR, 2.44; p < 0.01), those who did not eat quickly at baseline and after four years vs. those who did not eat quickly at baseline but did so after four years (OR, 2.42, p < 0.05) and those who did not eat quickly at baseline but did so after four years vs. those who ate quickly at baseline and after four years (OR, 2.31, p < 0.001) after adjusting for sex, age, Brinkman index, eating fast, skipping breakfast and eating snacks after dinner (Table 4).

Discussion

This study assessed the relationship between eating behavior and poor glycemic control among Japanese adults who presented for routine health checks. The results indicated that a high frequency of skipping breakfast as well as being male, older and rapidly consuming food predicted risk of poor glycemic control in the present population. These findings were consistent with previous cross-sectional9,10 and cohort11,12,13 studies that associated skipping breakfast with a possible risk of diabetes.

Accumulating evidence has associated skipping breakfast with the possibility of poor glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. For instance, skipping breakfast is significantly associated with higher HbA1c values, even after adjusting for age, sex, race, BMI, number of diabetes complications, insulin therapy, depressive symptoms, perceived sleep debt, and ratios (%) of daily caloric intake at dinner in patients with type 2 diabetes14. Habitually skipping breakfast concomitant with late evening meals might affect the ability of young male workers with type 2 diabetes to achieve and maintain glycemic control15. Furthermore, a randomized clinical trial found that skipping breakfast increased postprandial hyperglycemia after lunch and dinner in patients with diabetes16. On the other hand, the present study identified a positive relationship between a high frequency of skipping breakfast and poor glycemic control. The previous and present findings suggest that eating breakfast is important to maintain optimal glycemic control.

Omitting breakfast might reduce free-living physical activity and endurance exercise performance throughout the day17,18,19. Skipping breakfast could increase the risk of poor glycemic control through decreasing in physical activity and performance. In addition, a randomized controlled crossover trial found more 24-h energy expenditure on days when breakfast was skipped (+41 kcal/day) compared with control days when three meals were consumed20.

Our findings also showed that the risk of poor glycemic control was increased in participants who ate quickly after adjustment for sex, age, Brinkman index, regular exercise, skipping breakfast and having dinner within two hours of bedtime. Changing from not eating quickly to rapidly eating meals also persisted as a risk factor for poor glycemic control. Previous studies have positively correlated eating quickly with increased BMI21,22, which is an established risk factor for the progression of diabetes-associated complications23,24. Eating quickly might indirectly increase risk for poor glycemic control through increasing BMI.

Furthermore, we found here that risk of poor glycemic control did not significantly correlate with the frequency of consuming dinner within two hours of bedtime and eating snacks after dinner except when eating snacks after dinner changed from ≥3 to <3 times/week (Table 3). These findings differ from previous results in which the OR of late-night dinner consumption and hyperglycemia defined as HbA1c ≥5.7% and/or pharmacotherapy for diabetes was 1.128. Our definition of poor glycemic control differed from theirs. The relationship between late food consumption and glycemic status might vary according to the definition of poor glycemic control. In addition, our survey of the frequency of consuming dinner within two hours of bedtime and eating snacks after dinner might have a social desirability bias, suggesting that differences between the previous and present observations might be due to methodological issues associated. More data about meal patterns from a food diary, are needed to resolve this issue.

We excluded 481 (5.3%) patients with poor glycemic control at baseline and the prevalence after followup was about 2.0%. A previous cohort study found that the age-standardized prevalence of diabetes among Japanese adults aged 55–74 years was initially 8.2%, and 10.6% five years later25. Another study of Japanese adult men and women aged 20–69 years also found 8.0% and 3.3% prevalences of diabetes, respectively26. These findings collectively suggest that the prevalence of poor glycemic control in the present study population was relatively low. We recruited participants from a population who attended health checks at Asahi University Hospital. Since this cohort might have been particularly aware of or concerned with health, the ability to extrapolate our findings to the general population would be limited.

This study has other limitations. The validity of the questionnaire regarding eating behavior other than eating speed was not assessed. The data were limited because the data were derived from health-check findings. In addition, data regarding the quality of dietary intake and the frequency of consuming confectionery or sweet snacks will be required to improve the validity of our results. Furthermore, the participants defined dinner, snacks and breakfast. Therefore, the rationale for the ≥3 times/week cut-off for dinner within two hours of bedtime, eating snacks after dinner, and skipping breakfast will require confirmation.

In conclusion, the present findings of this study indicated positive associations between poor glycemic control and skipping breakfast ≥3 times/week, as well as between eating quickly, after adjusting for sex, age, Brinkman index and eating behavior.

Methods

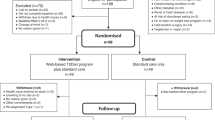

We analyzed data from community residents who participated in health checks at Asahi University Hospital in Gifu, Japan. A total of 9,132 Japanese adults aged ≥40 years participated in the baseline survey between January and December 2013. We excluded 530 residents without HbA1c data (n = 49), with HbA1c ≥6.5% (n = 324), and those under medication for diabetes and/or insulin therapy (n = 157). We excluded 48 residents because of missing information about eating behavior. Among 8,554 residents, 5,479 were followed up between January and December 2017 (follow-up rate, 64%). Accordingly, we analyzed data from 5,479 community residents in this study, which was approved by the Ethics Committee at Asahi University (No. 27010) and proceeded in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All the residents provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Measurement of HbA1c

We determined HbA1c values using the diabetes automatic analyzer (DM-JACK, Kyowa Medex, Tokyo, Japan) in venous blood samples collected after an overnight fast27,28.

Evaluation of poor glycemic control

In general, 0.5% HbA1c is considered a clinically significant change29 and ≥6.5% indicates poor glycemic control30. Therefore, our participants with HbA1c that reached ≥6.5% with increases of ≥0.5% were defined as having poor glycemic control at follow-up. In addition, some participants received diabetes medications after follow-up, although they did not meet our definition of poor glycemic control. However, since the participants who were under medication had already been diagnosed with diabetes, they were also included in the group with poor glycemic control.

Assessment of body composition

Height and body weight were measured using an automatic height scale with body composition meters (TBF-110/TBF-210/DC-250; Tanita Corp., Tokyo, Japan)27. We calculated BMI as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2).

Questionnaire

We used the same questionnaire as is used for the health check-ups in Japan. Information about age, sex, presence or absence of regular exercise (absence/presence), walking speed (slow/not slow), alcohol consumption (every day/not every day), eating behavior comprising speed (slowly, medium, or quickly), dinner within two hours of bedtime ≥3 times/week (yes/no), eating snacks after dinner ≥3 times/week (yes/no), and skipping breakfast ≥3 times/week (yes/no)31,32. We previously validated self-reported quick eating in the questionnaire33. In that study, participants who reported quickly spent less time chewing (rice balls) than those who reported eating slowly or a medium speed).

Evaluation of smoking status

The Brinkman index (daily number of cigarettes × years) was recorded as their smoking status34.

Statistical analysis

The normality of our data was confirmed using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Because all continuous variables were not normally distributed, data are expressed as medians (first and third quartiles). Significant differences in selected characteristics between study participants who skipped breakfast ≥3 times/week or not and ate rapidly were assessed at baseline using chi-square tests and Mann-Whitney U tests. Univariate and multivariate stepwise logistic regression analyses proceeded with the presence or absence of poor glycemic control as dependent variables. Variables with p < 0.10 were removed from the model and those with p < 0.05 were added. The model included groups with different types of behavior as the independent variable (Table 3). Other independent variables with p < 0.05 in the univariate model were selected. In addition, a variable with |r| > 0.8 in the spearman correlation analysis of between each variable was removed to avoid multicollinearity35. The ORs and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for each potential risk factor. All data were analyzed using SPSS statistics version 24 (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). All reported values with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

References

Bloomgarden, Z. T. Diabetes complications. Diabetes Care. 27, 1506–1514 (2004).

Lee, J. R., Yeh, H. C. Trends in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes and its association with mortality rates in Asians vs. Whites: Results from the United States National Health Interview Survey from 2000 to 2014. J Diabetes Complications. in press (2018).

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey Japan, 2016. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/04-Houdouhappyou-10904750-Kenkoukyoku-Gantaisakukenkouzoushinka/kekkagaiyou_7.pdf (Accessed May 1, 2018).

Koenig, R. J. et al. Correlation of glucose regulation and hemoglobin A1c in diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 295, 417–420 (1976).

Little, R. R. & Rohlfing, C. L. The long and winding road to optimal HbA1c measurement. Clin Chim Acta. 418, 63–71 (2013).

Bi, H. et al. Breakfast skipping and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 18, 3013–3019 (2015).

Radzevičienė, L. & Ostrauskas, R. Fast eating and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a case-control study. Clin Nutr. 32, 232–235 (2013).

Nakajima, K. & Suwa, K. Association of hyperglycemia in a general Japanese population with late-night-dinner eating alone, but not breakfast skipping alone. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 14, 16 (2015).

Nishiyama, M., Muto, T., Minakawa, T. & Shibata, T. The combined unhealthy behaviors of breakfast skipping and smoking are associated with the prevalence of diabetes mellitus. Tohoku J Exp Med. 218, 259–264 (2009).

Voronova, N. V., Nikitin, A. G., Chistiakov, A. P. & Chistiakov, D. A. Skipping breakfast is correlated with impaired fasting glucose in apparently healthy subjects. Cent Eur J Med. 7, 376–382 (2012).

Mekary, R. A., Giovannucci, E., Willett, W. C., van Dam, R. M. & Hu, F. B. Eating patterns and type 2 diabetes risk in men: breakfast omission, eating frequency, and snacking. Am J Clin Nutr. 95, 1182–1189 (2012).

Mekary, R. A. et al. Eating patterns and type 2 diabetes risk in older women: breakfast consumption and eating frequency. Am J Clin Nutr. 98, 436–443 (2013).

Uemura, M. et al. Breakfast Skipping is positively associated with incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: evidence from the Aichi workers’ cohort study. J Epidemiol. 25, 351–358 (2015).

Reutrakul, S. et al. The relationship between breakfast skipping, chronotype, and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Chronobiol Int. 31, 64–71 (2014).

Azami, Y. et al. Long working hours and skipping breakfast concomitant with late evening meals are associated with suboptimal glycemic control among young male Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. in press (2018).

Jakubowicz, D. et al. Fasting until noon triggers increased postprandial hyperglycemia and impaired insulin response after lunch and dinner in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 38, 1820–1826 (2015).

Betts, J. A. et al. The causal role of breakfast in energy balance and health: a randomized controlled trial in lean adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 100, 539–547 (2014).

Clayton, D. J. & James, L. J. The effect of breakfast on appetite regulation, energy balance and exercise performance. Proc Nutr Soc. 75, 319–327 (2016).

Zakrzewski-Fruer, J. K., Wells, E. K., Crawford, N. S. G., Afeef, S. M. O. & Tolfrey, K. Physical activity duration but not energy expenditure differs between daily and intermittent breakfast consumption in adolescent girls: A randomized crossover trial. J Nutr. 148, 236–244 (2018).

Nas, A. et al. Impact of breakfast skipping compared with dinner skipping on regulation of energy balance and metabolic risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 105, 1351–1361 (2017).

Yamane, M. et al. Relationships between eating quickly and weight gain in Japanese university students: a longitudinal study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 22, 2262–2266 (2014).

Ohkuma, T. et al. Association between eating rate and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond). 39, 1589–1596 (2015).

Svensson, M. K. et al. The risk for diabetic nephropathy is low in young adults in a 17-year follow-up from the Diabetes Incidence Study in Sweden (DISS). Older age and higher BMI at diabetes onset can be important risk factors. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 31, 138–146 (2015).

Purnell, J. Q. et al. Impact of excessive weight gain on cardiovascular outcomes in type 1 diabetes: Results from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) study. Diabetes Care. 40, 1756–1762 (2017).

Kabeya, Y. et al. Descriptive epidemiology of diabetes prevalence and HbA1c distributions based on a self-reported questionnaire and a health checkup in the JPHC diabetes study. J Epidemiol. 24, 460–468 (2014).

Hu, H. et al. Hba1c, blood pressure, and lipid control in people with diabetes: Japan epidemiology collaboration on occupational health study. PLoS One. 11, e0159071 (2016).

Iwasaki, T. et al. Correlation between ultrasound-diagnosed non-alcoholic fatty liver and periodontal condition in a cross-sectional study in Japan. Sci Rep. 8, 7496 (2018).

Kawahara, T., Imawatari, R., Kawahara, C., Inazu, T. & Suzuki, G. Incidence of type 2 diabetes in pre-diabetic Japanese individuals categorized by HbA1c levels: a historical cohort study. PLoS One. 10, e0122698 (2015).

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2009. Diabetes Care. 32, S13–S61 (2009).

The International Expert Committee. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 32, 1327–1334 (2009).

Tajima, M. et al. Association between changes in 12 lifestyle behaviors and the development of metabolic syndrome during 1 year among workers in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Circ J. 78, 1152–1159 (2014).

Zhu, B., Haruyama, Y., Muto, T. & Yamazaki, T. Association between eating speed and metabolic syndrome in a three-year population-based cohort study. J Epidemiol. 25, 332–336 (2015).

Ekuni, D., Furuta, M., Takeuchi, N., Tomofuji, T. & Morita, M. Self-reports of eating quickly are related to a decreased number of chews until first swallow, total number of chews, and total duration of chewing in young people. Arch Oral Biol. 57, 981–986 (2012).

Hamabe, A. et al. Impact of cigarette smoking on onset of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease over a 10-year period. J Gastroenterol. 46, 769–778 (2011).

Hamada, S. R. et al. Development and validation of a pre-hospital “Red Flag” alert for activation of intra-hospital haemorrhage control response in blunt trauma. Critical Care. 22, 113 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The study was self-funded by the authors and their institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.I., A.H., T.A. and T.T. conceived and planned the project. T.I., K.W., A.O., F.D., T.K. and A.H. performed data entry. T.A. and T.T. wrote the body of the manuscript. T.I. conducted statistical analysis. T.T. organized and supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iwasaki, T., Hirose, A., Azuma, T. et al. Association between eating behavior and poor glycemic control in Japanese adults. Sci Rep 9, 3418 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39001-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39001-y