Abstract

Mg2Sn is a potential thermoelectric (TE) material that can directly convert waste heat into electricity. In this study, Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots are prepared by melting under an Ar atmosphere. The prepared ingots contain Mg vacancies (VMg) as point defects, which results in the formation of two regions: an Mg2Sn single-crystal region without VMg (denoted as the single-crystal region) and a region containing VMg (denoted as the VMg region). The VMg region is embedded in the matrix of the single-crystal region. The interface between the VMg region and the single-crystal region is semi-coherent, which does not prevent electron carrier conduction but does increase phonon scattering. Furthermore, electron carrier concentration depends on the fraction of VMg, reflecting the acceptor characteristics of VMg. The maximum figure of merit zTmax of 1.4(1) × 10−2 is realised for the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingot by introducing VMg. These results demonstrate that the TE properties of Mg2Sn can be optimised via point-defect engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thermoelectric (TE) materials, which are capable of converting waste heat into electricity, are expected to play a significant role in future energy utilisation and management1,2. The performance of TE materials is evaluated in terms of the dimensionless figure of merit, zT = S2σT/κ, and power factor PF = S2σ, where S, σ, T and κ are the Seebeck coefficient, electrical conductivity, absolute temperature and thermal conductivity, respectively. Recently, point defects (interstitials, vacancies and antisite defects) in TE materials have been recognised as an important factor that significantly affects the TE performance in the following two ways. First, the carrier concentration in a TE material can be optimised by tuning the fraction of point defects because they can act as acceptors or donors, which results in an increase in PF. Second, thermal conductivity can be reduced by introducing point defects because they can act as phonon scattering centres. Although enhanced zT values have been realised for a variety of TE materials via point-defect engineering3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15, the fraction of point defects has rarely been evaluated quantitatively. Thus, point-defect engineering cannot yet be considered an established strategy to enhance TE performance.

Recently, our group performed the crystal structure analysis of polycrystalline Mg2Si samples and quantitatively verified the presence of interstitial defects in the samples using single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD)16,17. In the present study, we focus on Mg2Sn with the same crystal structure as Mg2Si. Mg2Sn has been studied extensively as a potential TE material18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Xin et al.31 reported that an Sb-doped n-type polycrystalline Mg2Sn, Mg2.15Sn0.98Sb0.02 exhibited a zT value of 0.53 at 650 K (κ and PF are 4.7 W/mK and 3.9 W/mK2, respectively). Chen et al.22 reported that an Ag-doped p-type polycrystalline Mg2Sn, Mg2Sn + 0.5 at. % Ag exhibited a zT value of 0.30 at 450 K (κ and PF are 4.0 W/mK and 2.6 W/mK2, respectively). Despite these sufficiently high PF values, the κ values are also high, limiting the zT values lower than ~0.5. Although the importance of controlling point defects in Mg2Sn is highlighted in some literature29,31, quantitative analysis of point defects has not been performed so far.

Regarding the TE properties of pristine Mg2Sn, single crystals exhibited different S values depending on the preparation method, as shown in Table 118,19,20,21,22,23. Generally, different S values reflect differences in carrier concentration. Liu et al.32 predicted that possible point defects in Mg2Sn are Mg vacancies (VMg) at the 8c (1/4 1/4 1/4) site and Mg interstitial defects (Mgi) at the 4b (1/2 1/2 1/2) site. These point defects are ionised and generate hole and electron carriers in Mg2Sn, respectively, i.e. VMg → VMg2− + 2 h+ and Mgi → Mgi2+ + 2e−. Thus, it is suggested that the difference in S values between Mg2Sn single crystals prepared using different methods arises from varying fractions of VMg and/or Mgi. Li et al.23 reported that Mg2Sn single crystals exhibited anisotropic S values. However, it is possible that the fractions of VMg and/or Mgi in the single crystals used were different because each Mg2Sn single crystal along the [111], [1\(\bar{1}\)0], or [11\(\bar{2}\)] direction was prepared by cutting from different parts of one Mg2Sn single-crystal ingot.

To reveal the relationship between point defects and the TE properties of Mg2Sn, we prepared Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots by melting under an Ar atmosphere. In the prepared ingots, VMg exists as a point defect, the fraction of which was successfully evaluated by SC-XRD. Furthermore, the VMg fraction is controlled by changing the Ar pressure, PAr. We find a peculiar nanostructure relating to VMg via transmission electron microscope (TEM); the Mg2Sn single crystals with VMg form nanometer-sized regions and are embedded in the Mg2Sn single-crystal region without VMg. The TE properties (|S|, σ and κ) of the ingots all decrease with increasing VMg because of a decrease in the electron carrier concentration and an enhancement of phonon scattering. In particular, the κ value is extremely low compared with that of polycrystalline Mg2Sn reported in the literature28, which is discussed in relation to the nanostructure of the ingots.

Results and Discussion

Phase characterisation and crystal structure refinement

Figure 1 shows the powder XRD patterns of the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots prepared under PAr = 0.6, 1.3 and 1.6 atm (hereafter, these ingots are referred to as the 0.6-, 1.3- and 1.6-atm ingots, respectively). All of the XRD peaks are well indexed to the expected Mg2Sn phase, except for a small peak assigned to an Mg secondary phase found for the 1.3- and 1.6-atm ingots. The bulk XRD measurements confirm the high crystallinity of the ingots. In the bulk XRD patterns, peaks corresponding to the 111, 222 and 333 planes are found (Fig. S1a). In addition, the full width at half maximum of the rocking curves of the 111 peak are as small as 317.3, 438.8 and 453.9 arcsec for the 0.6-, 1.3- and 1.6-atm ingots, respectively (Fig. S1b). A homogeneous distribution of the constituent elements is observed in the SEM-EDX mapping images of the Mg2Sn(111) cleavage surface, as shown in Fig. S2, further verifying the high quality of the prepared ingots. The Mg secondary phase is not observed in the SEM-EDX images because of its insignificant amount.

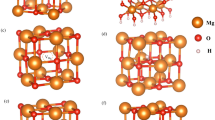

Single-crystal structure refinement was performed to evaluate the fraction of point defects (a detailed description can be found in the Supporting Information). As shown in Fig. 2a, the lattice constant decreases from 6.7625(2) Å to 6.7576(2) Å with increasing PAr, suggesting a change in chemical composition and/or mutual substitution between Mg and Sn. In other words, the fraction of point defects changes. In fact, the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots contain VMg, the fraction of which increases from 5.6(15)% to 12(3)% with increasing PAr (Fig. 2b). The presence of VMg is confirmed by the inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) measurement for the 0.6-atm ingot. These results indicate that the VMg fraction is controllable by changing PAr. The increase in VMg induced by increasing PAr can be attributed to the decreased formation energy of VMg, as reported for the case of Si that formation energy for a Si vacancy is calculated to decrease with increasing hydrostatic pressure38.

Nanostructure characterisation

The nanostructure of the 0.6-atm ingot was observed using TEM. Figure 3a shows a low-magnification TEM image, in which white and grey regions are observed. The grey regions are dispersed in the white region spread throughout the ingot. As shown in Fig. 3b, a high-magnification TEM image of the white region exhibits a perfect atomic arrangement of the Mg2Sn(111) surface, indicating that the white region corresponds to the Mg2Sn single-crystal region without VMg (denoted as the single-crystal region). This is confirmed by the fast Fourier transform (FFT) image of the white region, which shows the diffraction pattern of Mg2Sn along the [111] orientation (inset of Fig. 3b).

(a) Low-magnification transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of the 0.6-atm ingot. (b) High-magnification TEM image of the blue dashed square region in (a). The inset shows a fast Fourier transform (FFT) image of the white dashed square region. (c) High-magnification TEM image of the red dashed square region in (a), in which a parallel Moiré pattern is observed. (d) Size distribution of the parallel Moiré pattern corresponding to the location of the Mg2Sn single crystal with Mg vacancies (namely, the VMg region).

On the other hand, a high-magnification TEM image of the grey region exhibits a parallel Moiré pattern (Fig. 3c). Generally, a parallel Moiré pattern is observed when the electron beam of the TEM passes through two stacked crystals that have slightly different lattice constants3,39,40,41,42,43. Figure S4 shows a simple illustration of this situation. In the present study, the introduction of VMg into Mg2Sn reduces the lattice constant, as mentioned above (see Fig. 2a). Thus, it is conceivable that the observed parallel Moiré pattern originates from the stacking of the Mg2Sn single crystal with VMg on the single-crystal region. In other words, the Mg2Sn single crystals with VMg form nanometer-sized regions (denoted as VMg regions) that are distributed in the matrix of the single-crystal region. This means that VMg tends to aggregate in the ingot, which is considered to be energetically stable because the formation energy of point defects is generally lowered by clustering. The size distribution of the VMg regions was analysed, and it is plotted in Fig. 3d. The average size and density of the VMg region are 11 nm and 2.4(1) × 1014 m−2, respectively.

To further investigate the interface between the VMg region and the single-crystal region, an FFT image was produced from the area enclosed in the red dashed square in Fig. 4a, which covers both regions in the 0.6-atm ingot, as shown in the inset of Fig. 4a. The diffraction pattern of the single-crystal region (indicated by the white circles) and some extra spots (indicated by the red circles) are observed. Figure 4b shows the inverse FFT (IFFT) image generated from the diffraction pattern of the single-crystal region, which reproduces the regular atomic arrangement of the Mg2Sn(111) surface and is identical to that shown in Fig. 3b. In the IFFT image transformed from the extra spots, some aligned interference fringes are observed around the interface (the red solid line in Fig. 4c). As shown in the filtered IFFT image (Fig. 4d,e) obtained from the two spots in the inset of Fig. 4a (indicated by the red arrows), dislocations (red symbols) can be seen near the interference fringes. From the TEM observation of the 0.6-atm ingot, the dislocation density was evaluated to be 3.5 × 1016 m−2 in the ingot, indicating that the interface between the VMg region and the single-crystal region is semi-coherent. Such semi-coherent interfaces are often formed when the lattice mismatch between a precipitate and a matrix is sufficiently small3,39,40,41,42,43. The difference in the lattice constants between the Mg2Sn single crystals with and without VMg (corresponding to the VMg region and the single-crystal region) is smaller than 0.01 Å, as can be seen in Fig. 2a, which can be an origin of the formation of the semi-coherent interface.

(a) High-magnification TEM image of the 0.6-atm ingot. The inset shows a FFT image of the red dashed square region, including the Mg2Sn single-crystal regions with and without VMg. Using the diffraction spots marked with the white circles and red circles in the inset, inverse FFT (IFFT) images were generated, as shown in (b,c), respectively. (d) IFFT image transformed from the two spots indicated by red arrows in the inset of (a). (e) Magnified image of the blue dashed region in (d). Dislocations are marked in orange in (d,e).

Thermoelectric properties measurements

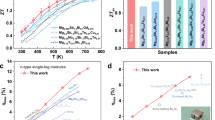

In addition to changing the carrier concentration, the introduction of VMg may cause carrier and phonon scattering through the formation of nanosized VMg regions and semi-coherent interfaces. To reveal the relationship between the VMg fraction and the electrical properties of the Mg2Sn, the Seebeck coefficient, S, and the electrical conductivity, σ, of the 0.6-, 1.3- and 1.6-atm ingots were measured. The temperature dependence of S is shown in Fig. 5a. All ingots exhibit negative S, i.e. the majority carriers are electrons, which is also confirmed by the negative Hall coefficient of the ingots measured at 300 K. The |S| value at 300 K decreases from |−166| μV/K to |−115| μV/K as PAr increases, indicating that the electron carrier concentration is different for each ingot. Upon the increase of the temperature, the differences between the |S| values diminish and become negligible above 450 K. These tendencies are attributed to the enhanced bipolar diffusion because Mg2Sn is narrow band gap semiconductor21,23,44,45. Figure 5b shows the temperature dependence of σ. The ingots exhibit similar σ values over the entire measurement temperature range. The σ value at 300 K slightly decreases from 32 S/cm to 26 S/cm as PAr increases.

The S and σ values at 300 K are plotted against the VMg fraction in the insets of Fig. 5a,b, respectively. To determine the reason for the decrease in both |S| and σ with increasing VMg fraction, the electron carrier concentration, n, at 300 K was evaluated from Hall effect measurements. Figure 5c shows that n decreases from 2.23(3) × 1018 cm−3 to 1.25(1) × 1018 cm−3 with increasing VMg fraction, indicating that VMg acts as an acceptor and cancels a part of the electron carriers in Mg2Sn. The change rate of per percentage unit of VMg is 1 × 1017 cm−3%−1. Generally, |S| should increase with decreasing n; however, |S| decreases in the present study. The controversial behaviour can be explained by assuming that the Fermi level is located near the middle of the band gap. This assumption is reasonable because the ingots are considered intrinsic semiconductors, which is supported by the tendency of σ and |S| of the ingots to increase and decrease with increasing temperature, respectively, and the fact that the σ values at 300 K are as low as several tens of S/cm. In this case, the |S| value decreases as the Fermi level moves toward the middle of the band gap upon increasing the VMg fraction, which is what we observed for the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots in the present study. Turning to the relation between σ and n, the rate at which σ decreases is lower than that for n. This means that the carrier mobility, μ, increases with increasing VMg fraction. As shown in Fig. 5d, μ increases from 89.9(8) cm3/Vs to 132.6(28) cm3/Vs, which is inversely proportional to n. Such a relation between n and μ has also been reported for an Mg2Si single crystal46. The μ values of the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots as a function of n is shown in the inset in Fig. 5d, which are on an extrapolated line from the reported data of Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots21,23, implying that VMg does not act as a carrier scattering centre. From these results, it is concluded that the introduction of VMg actually changes n in the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots, but does not affect μ, probably owing to the semi-coherent interface between the VMg region and the single-crystal region. We should recall that the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots prepared in this study are not uniform in morphology; the VMg regions are dispersed in the single-crystal region. Thus, the σ, S, n and μ values described above are macroscopic physical properties over the whole ingot, i.e., they are actually weighed means considering the contributions from the VMg regions and the single-crystal region. The changes in the σ, S, n and μ values with increasing VMg fraction originate from the different σ, S, n and μ values between the VMg regions and the single-crystal region. In other words, the VMg regions have lower σ, S and n values and higher μ value than the single-crystal region.

Next, the thermal conductivity, κ, of the 0.6-, 1.3- and 1.6-atm ingots was measured (Fig. 6a). As PAr increases, i.e. the VMg fraction increases, κ significantly decreases. The 1.6-atm ingot exhibits lower κ than the Mg2Sn single crystals and polycrystals reported in previous literatures21,23,25,30. The minimum κ of 3.75(2) W/mK is realised for the 1.6 atm ingot at 450 K. By subtracting the carrier thermal conductivity, κe (Fig. S5a), and the bipolar thermal conductivity, κbp (Fig. S5b), from κ, the lattice thermal conductivity, κL, was estimated as shown in Fig. 6b. (For the estimation of κe, we used the Wiedemann-Frantz law. The deviation of the estimation and the details of the κe and κbp calculations are given in the Supporting Information.) Upon the increase of PAr, the κL value of the ingots approaches the minimum calculated κL reported in the literature31. The lowest κL of 1.47(1) W/mK is recorded for the 1.6-atm ingot at 650 K, which is still lower than the literature values21,23,28,47.

To elucidate the reason for this low κL, κL was calculated using the Debye model48.

where \(\hslash \), ω, kB, v, θD and τtot are the reduced Plank constant, phonon frequency, Boltzmann constant, average sound velocity, Debye temperature and total relaxation time for phonon scattering, respectively. Considering the presence of VMg and semi-coherent interfaces in the ingot, phonon scattering by point defects and dislocation cores, in addition to the Umklapp process, was included in the calculation. Under these assumptions, τtot is given by τtot−1 = τU−1 + τPD−1 + τDC−1, where τU, τPD and τDC are the relaxation times corresponding to the Umklapp process, point defects and dislocation cores, respectively. More details of the equations expressing these relaxation times and the relevant parameters, such as the average atomic mass, can be found in Tables S4 and S5. As can be seen in Fig. 6c, the calculated result matches well with the experimental κL of the 0.6-atm ingot. It is found that point defects originating from VMg significantly contribute to the lower κL of the ingot. By contrast, the dislocations at the interface between the VMg region and the single-crystal region have a smaller effect on κL compared with the point defects probably because the concentration of dislocations (3.5 × 1016 m−2) is lower than the concentration of point defects (1.3(3) × 1018 m−2). Therefore, it is concluded that VMg has the main effect of lowering κL of the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots, but the semi-coherent interface does not lead to as much phonon scattering as VMg.

Finally, the PF and zT values of the 0.6-, 1.3- and 1.6-atm ingots were calculated, and the results are plotted in Fig. 7a,b, respectively. At temperatures below 450 K, the PF value decreases with increasing PAr, reflecting the variation in |S| among the ingots. Above 450 K, the prepared ingots show similar PF values because the difference in S and σ between the ingots is small, but slightly higher PF values are obtained for the 0.6- and 1.3-atm ingots relative to the 1.6-atm ingot. The highest PF is 0.11(1) mW/mK2 at 650 K for the 1.3-atm sample. Regarding zT, the 0.6- and 1.3-atm ingots show higher zT values than the other ingots in the temperature ranges from 300 to 400 K and from 400 to 650 K, respectively. The maximum zT value is 1.4(1) × 10−2 at 650 K for the 1.3-atm ingot mainly because of its low κ. In this study, we have succeeded in evaluating the VMg fraction in Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots. The TE properties are optimised by controlling the VMg fraction, demonstrating that point-defect engineering is an effective strategy to enhance the PF and zT of Mg2Sn. The superiority of the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots with VMg prepared in this study is low κ, but PF and zT are still low. (The comparison of κmin, PFmax and zTmax of the 0.6-, 1.3- and 1.6-atm with those of other Mg2Sn single crystals reported in the literatures21,23 is shown in Fig. S6.) By combining the reduction of κL (<1.5 W/mK) via point defect engineering, as in this study, with the enhancement of PF (~4.0 mW/mK2) via a conventional doping method31, a higher zT value (zT > 0.9 at 650 K) can be achieved for a Mg2Sn single crystal.

Methods

Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots were synthesised by melting using a one-zone-controlled resistive-heating furnace. Mg grains (4 N, Mitsuwa Chemicals Co., Ltd, 4 × 4 mm) and Sn powder (4 N, Kojundo Chemical Lab., 63 μm pass) were weighed and charged into a boron-nitride-coated alumina crucible in a molar ratio of Mg:Sn = 2.2:1. The crucible was then enclosed in a quartz tube under an Ar atmosphere of pressure, PAr = 0, 0.6, 1.3, or 1.6 atm at room temperature. The tube was heated to 1093 K over 9 h, then cooled to 973 K slowly over 48 h and finally cooled to room temperature over 9 h.

The crystalline phases and crystallinity of the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots were investigated by powder and bulk X-ray diffraction (XRD) using Cu Kα radiation (D8 ADVANCE, Bruker AXS). For the bulk XRD measurements, the Mg2Sn(111) cleavage surface was used. Moreover, a rocking curve of the 111 peak was measured. Owing to the difficulty in crystal structure refinement using the powder XRD patterns of Mg2Sn, as was the case for Mg2Si16,17, the fraction of point defects was evaluated via single-crystal XRD (SC-XRD) using Mo Kα radiation (D8 VENTURE, Bruker AXS). Small Mg2Sn single-crystal particles with typical dimensions of 40 μm × 60 μm × 60 μm, selected from fractured Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots, were used for the SC-XRD measurements. Single-crystal structure refinement was performed using the JANA2006 crystallographic computing system49. The fraction of point defects was also examined by inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Agilent 8800 ICP-QQQ, Agilent Technologies). The morphology and nanostructure of the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots were observed using a scanning electron microscope equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (SEM-EDX; JSM-IT100, JEOL) and a field-emission-type TEM (JEM-2100F, JEOL).

The Seebeck coefficient, S, and the electrical conductivity, σ, of the Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots were measured in vacuum using an automated thermoelectric tester (RZ2001i, Ozawa Science Co.). The Hall coefficient, RH, was measured using a physical properties measurement system (PPMS, Quantum Design) at 300 K by sweeping the magnetic field from −5.0 T to 5.0 T. The carrier concentration, n, and carrier mobility, μ, were calculated using the equations n = |1/(eRH)| and μ = σRH, respectively, where e is the elementary charge. The thermal conductivity, κ, was measured in vacuum using a standard laser flash analyser (TC-7000, ULVAC-RIKO).

References

Goldsmid, H. J. Applications of thermoelectricity; Methuen Monograph: London (1960).

Rowe, D. M. Thermoelectrics Handbook Macro to Nano; CRC Press: Boca Raton (2006).

Kim, S. I. et al. Dense Dislocation Arrays Embedded in Grain Boundaries for High-performance Bulk Thermoelectrics. Sci 348, 109–114 (2015).

Li, J. et al. Low-Symmetry Rhombohedral GeTe Thermoelectrics. Joule 2, 976–987 (2018).

Day, T. et al. Influence of Compensating Defect Formation on the Doping Efficiency and Thermoelectric Properties of Cu2−ySe1−xBrx. Chem. Mater. 27, 7018–7027 (2015).

Jiang, G. et al. High Performance Mg2 (Si,Sn) Solid Solutions: a Point Defect Chemistry Approach to Enhancing Thermoelectric Properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 3776–3781 (2014).

Zhu, T. et al. New Insights into Intrinsic Point Defects in V2VI3 Thermoelectric Materials. Adv. Sci. 3, 160004 (2016).

Xin, J. et al. Mg Vacancy and Dislocation Strains as Strong Phonon Scatterers in Mg2Si1−xSbx Thermoelectric Materials. Nano Energy 34, 428–436 (2017).

Hu, L. et al. Point Defect Engineering of High-Performance Bismuth-Telluride-Based Thermoelectric Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 5211–5218 (2014).

Li, Z. et al. Defect Chemistry for Thermoelectric Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 14810–14819 (2016).

Chen, Z. et al. Lattice Dislocations Enhancing Thermoelectric PbTe in Addition to Band Convergence. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606768 (2017).

Bhat, D. K. & Shenoy, S. U. High Thermoelectric Performance of Co-Doped Tin Telluride Due to Synergistic Effect of Magnesium and Indium. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 7123–7130 (2017).

Shenoy, S. U. & Bhat, D. K. Enhanced Bulk Thermoelectric Performance of Pb0.6Sn0.4 Te: Effect of Magnesium Doping. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 20696–20703 (2017).

Shenoy, S. U. & Bhat, D. K. Bi and Zn Co-doped SnTe Thermoelectrics: Interplay of Resonance Levels and Heavy Hole Band Dominance Leading to Enhanced Performance and a Record High Room Temperature ZT. J. Mater. Chem. C, https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TC06490G (2020).

Bhat, D. K. & Shenoy, S. U. Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance of Bulk Tin Telluride: Synergistic Effect of Calcium and Indium Co-doping. Mater. Today Phys. 4, 12–18 (2018).

Kubouchi, M. et al. Quantitative Analysis of Interstitial Mg in Mg2Si Studied by Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction. J. Alloys Compd. 617, 389–392 (2014).

Kubouchi, M. et al. Effect of Interstitial Mg in Mg2+xSi on Electrical Conductivity and Seebeck Coefficient. J. Electron. Mater. 45, 1589–1593 (2015).

Chen, H. Y. & Savvides, N. Microstructure and Thermoelectric Properties of n- and p-Type Doped Mg2Sn Compounds Prepared by the Modified Bridgman Method. J. Electron. Mater. 38, 1056–1060 (2009).

Chen, H. Y. & Savvides, N. Eutectic Microstructure and Thermoelectric Properties of Mg2Sn. J. Electron. Mater. 39, 1792–1797 (2010).

Kim, S. et al. Electronic Structure and Thermoelectric Properties of P-type Ag-doped Mg2Sn and Mg2Sn1−xSix (x = 0.05, 0.1). J. Appl. Phys. 116, 153706 (2014).

Chen, H. Y. & Savvides, N. Thermoelectric Properties and Microstructure of Large-Grain Mg2Sn Doped with Ag. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1166 (2009).

Chen, H. Y. et al. Electronic and Thermal Transport Properties of Mg2Sn Crystals Containing Finely Dispersed Eutectic Structures. Phys. Status Solidi A 207, 2523–2531 (2010).

Li, X. et al. Anisotropy of Seebeck Coefficient in un-doped Mg2Sn Single Crystal. Intermetallics 81, 26–31 (2010).

Varma, R. R. et al. Effect of Magnesium and Silver Doping on the Thermoelectric Performance of Cast Mg2Sn Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 757, 142–149 (2018).

Winkler, U. Die elektrischen Eigenschaften der intermetallischen Verbindungen Mg2Si, Mg2Ge, Mg2Sn und Mg2Pb. Helv. Phys. Acta 28, 633–666 (1955).

Zaitsev, V. K. et al. Width of Forbidden Band in Solid Solutions Mg2Si-Mg2Sn. Sov. Phys. Solid State 11, 3000–3002 (1969).

Aizawa, T. & Song, R. Mechanically Induced Reaction for Solid-state Synthesis of Mg2Si and Mg2Sn. Intermatellics 14, 382–391 (2006).

An, T. et al. Enhancement of p-type Thermoelectric Properties in an Mg2Sn System. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 60, 1717–1723 (2012).

Mao, J. et al. Thermoelectric Performance Enhancement of Mg2Sn Based Solid Solutions by Band Convergence and Phonon Scattering via Pb and Si/Ge Substitution for Sn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 20726–20737 (2016).

Tani, J. et al. Thermoelectric Properties of Impurity-Doped Mg2Sn. J. Electron. Mater. 48, 3330–3335 (2019).

Xin, J. et al. Multiscale Defects as Strong Phonon Scatters to Enhance Thermoelectric Performance in Mg2Sn1−xSbx Solid Solutions. Small Methods 1900412 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Significant Roles of Intrinsic Point Defects in Mg2X (X = Si, Ge, Sn) Thermoelectric. Materials. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2, 1500284 (2016).

Jin, Y. et al. Mg2Sn: a Potential Mid-temperature Thermoelectric Material. RSC Adv. 6, 48728–48736 (2016).

Tani, J. & Kido, H. Impurity Doping into Mg2Sn: A First-Principles Study. Physica B 407, 3493–3498 (2012).

Pulikkotil, J. J. et al. Doping and Temperature Dependence of Thermoelectric Properties in Mg2(Si,Sn). Phys. Rev. B 86, 155204-1–8 (2012).

Safavi, M. et al. Thermoelectric Properties Improvement in Mg2Sn Thin Films by Structural Modification. J. Alloys Compd. 692, 137601 (2019).

Tani, J. & Ishikawa, H. Thermoelectric Properties of Mg2Sn Thin Films Fabricated Using Radio Frequency Magnetron Sputtering. Thin Solid Films 404, 4558–4560 (2019).

Gusakov, V. et al. Formation of Frenkel Pairs and Diffusion of Self-Interstitial in Si Under Normal and Hydrostatic Pressure: Quantumchemical Simulation. Physica B 404, 4558–4560 (2009).

Murray, C. B. et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Nearly Monodisperse Cd E (E = Sulfur, Selenium, Tellurium) Semiconductor Nanocrystallites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 8706–8715 (1993).

Chadderton, L. T. et al. Stacking Faults in Cadmium Sulphide. Nature 198, 573–574 (1963).

Rhyee, J.-S. et al. Peierls Distortion as a Route to High Thermoelectric Performance in In 4Se3-б Crystals. Nature 459, 965–968 (2009).

Perumal, S. et al. Low Thermal Conductivity and High Thermoelectric Performance in Sb and Bi Codoped GeTe: Complementary Effect of Band Convergence and Nanostructuring. Chem. Mater. 29, 10426–10435 (2017).

Zhou, M. et al. Nanostructured AgPbmSbTem+2 System Bulk Materials with Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 4527–4532 (2008).

Shenoy, S. U. & Bhat, D. K. Electronic Structure Engineering of Tin Telluride Through Co-doping of Bismuth and Indium for High Performance Thermoelectrics: a Synergistic Effect Leading to a Record High Room Temperature ZT in Tin Telluride. J. Mater. Chem. C 7, 4817–4821 (2019).

Bhat, D. K. & Shenoy, S. U. Zn: A Versatile Resonant Dopant for SnTe Thermoelectrics. Mater. Today Phys. 100158, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtphys.2019.100158 (2019).

Udono, H. et al. Crystal Growth and Characterization of Mg2Si for IR-Detectors and Thermoelectric Applications. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 54, 07JB06 (2015).

Martin, J. J. Thermal Conductivity of Mg2Si, Mg Ge and Mg2Sn. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 33, 1139–1148 (1972).

Callawey, J. & Vonbaeyer, H. C. Effect of Point Imperfections on Lattice Thermal Conductivity. Phys. Rev. 120, 1149–1154 (1960).

Petricek, V. et al. Crystallographic Computing System JANA2006: General features. Z. Kristallogr. 229, 345–352 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Mr. K. Yoza from the single-crystal diffraction application at Bruker Japan for part of the single-crystal XRD measurements. The authors are grateful to Mr. T. Miyazaki and Mr. S. Takahashi from the Instrumental Analysis Group at Tohoku University for the TEM and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry measurements. W.S. and K.H. are also grateful to Prof. H. Udono from the Faculty of Engineering at Ibaraki University for his advice on fabricating high-quality Mg2Sn single-crystal ingots. This work was partly supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (No. 17H03398) and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (No. 17H05207) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, and by Tsinghua-Tohoku Collaborative Research Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.S. performed the synthesis of ingots, XRD, SEM and thermoelectric measurements and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. K.H. contributed to discussion of data and assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. J.D. and J.-F.L. contributed to discussions. Y.M. supervised the project and contributed to discussions and writing. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saito, W., Hayashi, K., Dong, J. et al. Control of the Thermoelectric Properties of Mg2Sn Single Crystals via Point-Defect Engineering. Sci Rep 10, 2020 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58998-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58998-1

This article is cited by

-

Thermodynamic and thermoelectric properties of titanium oxycarbide with metal vacancy

International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials (2022)