Abstract

In topological insulators (TIs), carriers originating from non-stoichiometric defects hamper bulk insulation. In (Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)3 TIs (BSTS TIs), however, Se atoms strongly prefer specific atomic sites in the crystal structure (Se ordering), and this ordering structure suppresses the formation of point defects and contributes to bulk insulation. It has accelerated the understanding of TIs’ surface electron properties and device application. In this study, we select Pb(Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)4 (Pb-BSTS) TIs, which are reported to have larger bandgap compared to counterpart compound BSTS TIs. The Se ordering geometry was investigated by combining state-of-the-art scanning transmission electron microscopy and powder X-ray diffractometry. We demonstrated the existence of inner Se ordering in PbBi2(Te,Se)4 and also in Pb-BSTS TIs. Quantitative analysis of Se ordering and a qualitative view of atomic non-stoichiometry such as point defects are also presented. Pb-BSTS TIs’ Se ordering structure and their large gap nature has the great potential to achieve more bulk insulation than conventional BSTS TIs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1980, the Quantum Hall Effect (QHE) was first discovered by Klitzing et al.1. In the QHE system, the peculiar topology of band structure yields boundary states called skipping edge states in which backscattering is completely prohibited2. Since then, the importance of the band structure topology has come to be recognized3,4. The drawback of the QHE system is that strong magnetic field is required to generate such special states, which hampers its device application. However in 2005, the existence of such boundary states, even in zero magnetic field, was theoretically predicted5. This was confirmed experimentally by transport analyses and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) studies soon after its prediction6,7,8. This first developed material group possessing such boundary states is called topological insulators (TIs)9,10. The TIs’ surface states are an extension of 1D edge skipping electron in QHE2, and the surface states have exotic properties such as suppression of backscattering11,12 and spin polarized nature13. By using the spin polarized current14, spintronics devices with considerably lower power consumption can be obtained15. Intensive efforts for application have been made both from theoretically16 and experimentally15. In particular, Mellnik et al.15 succeeded in exerting a strong spin-transfer torque from the TI layer to an adjacent ferromagnetic layer, and changing the direction of magnetization in the ferromagnetic layer. This mechanism can be utilized in ultralow power logic technologies17 in next generation.

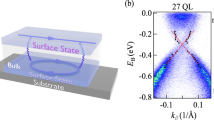

In the TIs field, tetradymite-type Bi2(Te,Se)3 (BTS TIs) and (Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)3 TI (BSTS TIs) have often been used for detecting and utilizing specific surface states18,19,20,21. In these materials, Se atoms predominantly occupy the center site of a quintuple(5)-layer structure (Se ordering)22, and are believed to suppress the formation of antisite defects21. The mechanism is as follows21: (i) the concentration of Se vacancy is reduced because the Se trapped between two Bi atoms is less exposed to evaporation due to stronger chemical bonding with Bi; (ii) antisite defects between Te and Bi is expected to be suppressed because of preferable bonding between Se-Bi compared to Se-Te bonding; (iii)ordered nature minimizes the additional disorder that could be caused by Se/Te randomness. In addition to Se ordering, chemical potential tuning by changing Bi/Sb ratio makes it possible to enhance the BSTSs’ bulk insulation to more than 1000 times higher than the non-doped sample20,21. These efforts allow one to verify the 2D nature of surface states, and to detect its π Berry phase23 and other important properties such as mobility by transport measurements18,20,21,24. However, even in such ideal samples, the utilization and detection of surface states remain a bit difficult for now. Therefore, many research groups search for new materials that have ideal properties, and as such Pb-based TIs (Pb-TIs) were rediscovered in the context of solid-state physics.

Pb(Bi,Sb)2Te4 is one of the Pb-TIs. It was theoretically predicted as TI in 201125,26, and experimentally verified in March27 and May28 of 2012 by two different groups, which demonstrates the intense competition in this field. Kuroda et al.28 showed that this material has more than twice larger density of surface electron than BSTS TIs when compared at the same Fermi energy from the Dirac point. This property makes Pb-TIs suitable candidates for spintronics research and application. Also, it is reported that this material belongs to a peculiar topological class (v0; v1v2v3) = (1; 111)25,28, while most of the other TIs like BSTS have (1;000)29. These nonzero indices originate from band inversion at the Z point; TIs with such indices are predicted to possibly have gapless dislocation states30,31. In the study by Souma et al.27, it was shown that the chemical potential of Pb(Bi,Sb)2Te4 can be tuned between the bulk band gap, and that it is always a strong TI. In response to these studies, the authors synthesized various Sb-concentration samples with fine Sb tuning, and succeeded in enhancing the bulk insulation approximately 400 times higher than non-doped one32,33. Its remaining bulk conduction was considered to come from impurity bands, and the magnetoresistance was quite well consistent with 3D-weak antilocalization scheme. Therefore, there should be random potential possibly coming from point defects and also local band-bending should occur. In such circumstances, an effective band gap Eeff, which is the activation energy in transport measurements, will become smaller34,35. The theoretical study has revealed Eeff will become Eeff = 0.15ΔEg in ordinal case34, which is consistent with activated energy in transport measurements20,21,32. To suppress the formation of such point defects and local band-bending, we began to focus on the Se ordering structure.

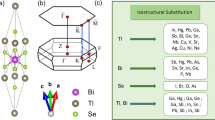

The substitution effect of Te by Se atoms in PbBi2Te4 was studied by some groups36,37,38. This material was first investigated in the 1970s as a natural mineral “poubaite”36, and it was found that its crystal structure is the same as that of PbBi2Te436. However, detailed crystal structure, such as site occupancy and the Se ordering structure, was not determined due to tiny crystal size (approximately 30 μm). After theoretical prediction as TI, the nanosheet of PbBi2Se4 was synthesized by Chatterjee et al.37 although the bulk sample of PbBi2Se4 with the crystal structure of \(R\mathop{3}\limits^{-}\) is unstable39. The observed band gap is 600 meV, which is considerably higher than that of counterpart compound Bi2Se3 (300 meV). As for theoretical research, the effect of the Se distribution geometry in PbBi2(Te,Se)4 was studied in 201738. It was reported that PbBi2(Te,Se)4 (Pb-BTS) can take 3 different Se geometry structures (Fig. 1a–c): (a) disordered; (b) outer Se ordering; and (c) inner Se ordering. They showed that the electronic structure strongly depends on Se atom geometry, and that the maximum band gap can be obtained in geometry (c). Considering the large bandgap37,38 and the defect suppressing nature of Se ordering21, it is expected that significantly more bulk insulation samples can be obtained if the inner Se ordering geometry really occurs in Pb-TIs. The bulk insulation strategy is the same as in BSTS TIs; however, larger bandgap has more potential to achieve better bulk insulation than BSTS TIs.

In this study, by combining state-of-the-art scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and powder X-ray diffractometry (pXRD), we studied the Se distribution geometry in PbBi2(Te,Se)4. In the STEM study, we directly observed the inner Se ordering in PbBi2(Te,Se)4 (Pb-BTS) TI. The pXRD study also revealed that the strong tendency of Se atoms to occupy the inner site, and 90–100% of Se atoms are considered to occupy inner Te/Se(2) site. Also, we discovered that this ordering also occurs in Pb(Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)4 (Pb-BSTS), which enables the bulk insulation by Fermi level tuning. A qualitative view of atomic non-stoichiometry such as point defects are also presented. These findings pave the pathway to develop a new TI material group possessing more bulk insulation than that of the conventional BSTS TIs.

Results and Discussions

Phase constitution of PbBi2(Te1-ySey)4 and Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2(Te1-ySey)4

The phase constitution and composition of the grown crystals were investigated by an electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA). In Fig. 2a, EPMA mapping of Pb-BTS (y = 0.5) is presented. Detailed information of characteristic X-ray is presented in the Supplementary Information. Phase PbBi2(Te1-ySey)4 (phase A) is indicated by blue arrows, and a detailed composition is listed in the Supplementary Information (S1). Phase A is always with other impurity phases Pb5Bi6(Te,Se)14 and PbTe. That is possibly due to complex phase diagram in PbSe-Bi2Se3 series compound, which includes several peritectic reactions39. In our synthesized rod, Pb5Bi6(Te,Se)14 seems to be originating from a peritectic reaction of PbTe + melt → Pb5Bi6(Te,Se)14. Contrastingly, Fig. 2b shows the EPMA-Pb mapping of Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2(Te1-ySey)4 sample (x = 0.8, y = 0.5). The phase distribution completely changes compared to Pb-BTS, and its microstructure is similar to that observed in Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4 (x = 0.6–0.9) Bridgman rod32. Single phase of Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2(Te1-ySey)4 (phase A’) can be easily picked out, which is good condition for the transport study both for bulk samples and nano exfoliated samples.

EPMA Pb mapping of (a) PbBi2(Te1-ySey)4 alloy system (y = 0.5); and (b) Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2(Te1-ySey)4 (x = 0.8, y = 0.5) system. The colormap is normalized for each picture. The length of black bar in all pictures is 200 μm. The region of the target compound Pb(Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)4 is indicated by blue arrows.

STEM observations

A cross-sectional high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) - STEM image of PbBi2(Te1-ySey)4 (y = 0.5) along [100] direction together with intensity profile is presented in Fig. 3a. This image is a drift corrected image using in-house software40. The unique septuple (7) layer structures are clearly observed and the thickness of one unit of a septuple layer is estimated to be 1.38 nm, which is in quite good agreement with the previous XRD crystal structure analyses results38. The intensity of the HAADF image is assumed to be proportional to Z2 in an ordinal condition41,42. From the intensity profile below, we can clearly see the inner Te/Se sites (Te/Se(2)) have weaker intensity than the outer Te/Se(1) sites. As the atomic number of Se (Z = 34) is less than Te (Z = 52), it is safe to assume that Se atoms mainly occupy the inner Te/Se(2) sites.

(a) HAADF raw image with intensity plot of the sample of PbBi2(Te1-ySey)4. (y = 0.5) Structure model is also presented; (b) experimental ABF-image (RL deconvoluted); and (c) simulated image of 100% inner ordered PbBi2(Te1-ySey)4 (y = 0.5); (d) HAADF-STEM; (e) EELS-Te mapping; and (f) EELS-Se mapping in the same area; (g) magnified HAADF image with intensity profile; (h) intensity is plotted along the blue, green, and red arrows.

In Fig. 3b, the annular bright-field (ABF)-STEM image of the same sample is presented. This image is processed by Richardson-Lucy software43 for resolution enhancement and noise reduction. The validity of denoising process is examined in the Supplementary Information, in which we compare deconvoluted image with raw image (S2). Briefly, ABF and HAADF-STEM images are produced by the convolution of scattering function of atomic column and the probe intensity profile of STEM system under the incoherent imaging approximation41. Therefore, to enhance the resolution of STEM image, the algorithm using deconvolution process, such as Richardson-Lucy (RL) deconvolution, is a powerful tool. In fact, Ishizuka et al.44 utilized these algorithms to enhance the spatial resolution in HAADF and energy resolution in EELS. We also tried the ABF-STEM image simulation (Fig. 3c) with a somewhat extreme condition: Te/Se(1): 100%Te, Te/Se(2): 100% Se. The simulated image is quite similar to the experimental one; thus the occupancy of the inner Te/Se(2) sites might be near 100% Se. We also admit that it is somewhat risky to determine site occupancy only from this image because of the background noise coming from the dechanneling effect; therefore, quantitative analysis on site occupancy was conducted by pXRD analyses and is discussed later.

Other than HAADF and ABF-STEM, recent breakthrough of STEM-EELS has led to finding ideal experimental conditions to suppress delocalization of probe electrons45,46, and atomic-resolution chemical mapping and analyses of atoms’ electron state have become possible45. Figure 3d–f were taken in the same area simultaneously, and they are HAADF-image (Fig. 3d), EELS chemical mapping of Te M4,5 edge (572 eV, Fig. 3e), and Se L2, L3 edges (1436 eV, Fig. 3f). The black arrows in Fig. 3d are single septuple layer. The Te intensity between septuple layer, that is Te/Se(1) sites, is high (Fig. 3e). Correspondingly, the Se intensity in the septuple layer (Te/Se(2)) is high (Fig. 3f). These facts also strongly suggest the inner Se ordering. Therefore, from all of the experimental results of HAADF, ABF-STEM, and STEM-EELS, we can conclude that the inner Se ordering actually occurs among three possible Se geometries38.

In addition to Se ordering, some information about local non-stoichiometry can be deduced from the STEM observation. In the previous paragraph, we showed that inner Se ordering occurs and Se occupancy in the Se layer might be nearly 100%, but this is an average structure. When we pay attention to the local structure, this outlook should be slightly altered. Figure 3g is taken in the same TEM sample of 3a. This image is also processed by RL software (for the validity, see the Supplementary Information S2). Although the intensity of Te, Bi, and Pb sites hardly changes in the image (see the equivalent peak intensity on the green line of Fig. 3h), there is an intensity fluctuation in the Se(2) layer (Fig. 3h). In some points, high intensity compatible to the outer Te layer is observed (row 4, 5 red). Also, they appear to form pairs with low intensity columns (row 4,5 blue) across the middle Pb sites (green arrow). Such intensity fluctuation might come from atomic level local non-stoichiometry. Such local non-stoichiometry cannot be measured by conventional XRD analyses, which yield the average structure. STM measurements also give information only about outermost layer of exfoliation layer. However, recent STEM technique allows one to obtain the information of atomic level local non-stoichiometry deep under topmost cleavage plane. For example, in the compound BAs, STEM study revealed that AsB and BAs form an antisite pair locally47 and proposed as the reason of low thermal Conductivity of this material. As for the local non-stoichiometry in Fig. 3g, the TeSe & SeTe antisite pair48 and the VSe & BiSe antisite49 pair might be the main candidates. In BSTS TIs, the TeSe and SeTe antisites defects are shown to be quite stable under almost all growth conditions48. The VSe & BiSe antisite pair is actually observed in Bi2Se3 by STEM observation49. In any case, such local non-stoichiometry is considered to cause local band-bending34,35 and charge puddles are generated35,50. More study is needed to elucidate such point defects nature, which is the key factor to enhance bulk insulation in TIs and understand its nature.

Quantitative analyses of Se occupancy by pXRD

The quantitative study of Se occupancy of Te/Se(1) and Te/Se(2) sites by pXRD is presented in this section. In pXRD measurements, a small DS slit angle was used to accurately evaluate the pXRD intensity in the lower 2 θ angle. The pXRD simulations were conducted using RIETAN-FP51. In Fig. 4a, the simulated pXRD data of three possible Se geometry: (1) disordered Se; (2) outer Se ordering; and (3) inner Se ordering are presented with experimental data. It should be noted here that we have a strong preferred orientation (PO) in our powder sample due to van der Waals cleavage nature of PbBi2(Te,Se)4 in parallel with (00h) plane. This inhibits a simple comparison of the experimental data with the simulated ones. Nevertheless, we should be allowed to make such comparison if we focus on a series of 00h peaks, because they should hold correct intensity ratios even if the PO effect is strong. In the simulated data, we can see that the intensity ratio of 003 and 006 strongly depends on the Se geometries. This originates from layer stacking order in the [001] direction and can be used for the geometry determination. Other factors that can affect the intensity ratio of 00h reflections are investigated in the Supplementary Information S3, and they are shown to give much less contribution than Se geometry. In the experimental data, we notice the trace of an impurity phase, which is identified as phase Pb5Bi6(Te,Se)14. However, if we compare 00h reflections of PbBi2(Te,Se)4, then the experimental data most fit the inner Se ordering simulation, which is consistent with earlier STEM results. In order to investigate Se occupancy quantitatively, we then set the occupancy of the Te/Se(2) sites as (i) Se 100%; (ii) Se 90% Te10%; and (iii) Se 80% Te 20%. Correspondingly, the occupancy of Te/Se(1) sites is (i) Te100%; (ii) Te90% Se10%; and (iii) Te80% Se20%, so that atomic ratio of Te and Se is 1:1 in total. The calculated patterns are presented in Fig. 4b. In the 80% ordering pattern, the intensities of 003 and 006 are almost same, but the experimental data are not. The value of I006/I003 is used for determining the Se occupancy accurately and the Te/Se(2) sites are considered to be approximately 95% occupied by Se atoms (inset in Fig. 4b). This value is in agreement with our ABF-STEM image simulation result. Also, the degree of Se ordering is in the same range of that reported in BSTS system52. As the Fermi level of PbBi2(Te,Se)4 is reported to cross the bulk conduction band38 and above the bandgap, lowering the Fermi level by Sb doping is needed to achieve bulk insulation. In the last section, Se ordering in Pb(Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)4, which has a large bulk bandgap and high potential for true bulk insulation, is investigated from the pXRD analysis.

(a) The simulated pXRD patterns of 3 different Se geometries and the experimental pXRD data of PbBi2(Te1-ySey)4 (y = 0.5); (b) pXRD simulation patterns with different Se ordering degree are presented with experimental data of PbBi2(Te1-ySey)4 (y = 0.5); (c) pXRD simulation patterns of different Se ordering in Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2(Te1-ySey)4 (x = 0.8, y = 0.5) are presented with experimental data.

In Fig. 4c, the pXRD data of Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2(Te1-ySey)4 (x = 0.8, y = 0.5) and the simulated pXRD data are presented. In the case of Pb-BSTS alloy, there is single phase region of target compound in Bridgman batch, so it is possible to single out only Pb-BSTS phase. Among the three possible Se geometries, the experimental data most fit the inner Se ordering and are completely distinct from others. Lastly, we would like to discuss the physical origin of the inner Se ordering. In general, atoms with high electronegativity (EN) tend to make chemical bonds with atoms with low EN, because it is energetically favorable53. In PbBi2(Te,Se)4, Se has the highest EN (=2.4). The EN of Te (2.1) is lower than that of Se, and those of Pb (1.8) and Bi (1.9) are even lower. In the layer structure shown in Fig. 1, the site of Te/Se (2) has three bonds with Pb and three bonds with Bi while the site of Te/Se (1) has three bonds with Bi and three bonds with Te/Se. Then, when Se and Te separately occupy the sites (2) and (1), respectively, i.e., in the inner Se ordering, the total energy should be the lowest. As the EN of Sb (1.8) is almost the same as that of Bi, Sb doping should not break the inner Se ordering. This material has the largest bandgap in the inner Se geometry38, and the Se ordering structure is considered to suppress the formation of antisite defects21. Therefore, if we can finely tune the chemical potential, truly bulk insulating samples, which is ideal for surface states utilization for spintronics should be obtained.

Conclusion

In this study, by combining state-of-the-art Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) and powder-XRD (pXRD) analysis, we studied the Se atoms distribution in Pb(Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)4 TIs. In the STEM study, we directly observed the inner Se ordering of PbBi2(Te,Se)4 TI. The pXRD study revealed the strong tendency of Se atoms to occupy the inner site, and that quantitatively nearly 95% of Se atoms occupy the inner Te/Se(2) site. A qualitative view of local non-stoichiometry such as point defects is also presented from STEM observations. Additionally, we found that this ordering also occurs in Pb(Bi,Sb)2(Te,Se)4, which enables the bulk insulation by Fermi level tuning changing Bi/Sb ratio. These findings will pave the pathway to realize more bulk insulation in Pb-BSTS TIs than BSTS TIs.

Method

Synthesis

As described in earlier report32, PbBi2(Te1-ySey)4 and Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2(Te1-ySey)4 crystals were grown using the Bridgman method. First, a mixture of high- purity (6N) Pb, Bi, Sb, Te and Se elements, in the stoichiometric molar ratio, was sealed in an evacuated quartz ampoule. Then, it was melted and homogenized at 800 °C, followed by water-quenching. Subsequently, the ingots were subjected to the Bridgman method for crystal growth. The ampoule translation speed was set at 2–2.5 mm/h. The temperature gradient in the furnace was approximately 25 °C/cm around the position of the liquidus temperature.

Specimen preparation and STEM observation

To investigate the Se distribution, TEM samples of the PbBi2(Te1-ySey)4 (y = 0.5) for [100] cross-sectional observation were prepared using conventional methods including mechanical polishing, dimple grinding and Ar ion polishing. STEM observation was performed using a 300-kV aberration-corrected electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Titan3).

References

Klitzing, K. V., Dorda, G. & Pepper, M. New Method for High-Accuracy Determination of the Fine-Structure Constant Based on Quantized Hall Resistance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 494 (1980).

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: Topological Insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045 (2010).

Thouless, D. J., Kohmoto, M., Nightingale, M. P. & den Nijs, M. Quantized Hall Conductance in a Two-Dimensional Periodic Potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 405 (1982).

Laughlin, R. B. Quantized Hall Conductivity in Two Dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5632(R) (1981).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Z2 Topological Order and the Quantum Spin Hall Effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 146802 (2005).

Bernevig, B. A., Hughes, T. L. & Zhang, S.-C. Quantum Spin Hall Effect and Topological Phase Transition in HgTe Quantum Wells. Science. 314, 1757 (2006).

König, M. et al. Quantum Spin Hall Insulator State in HgTe Quantum Wells. Science 318, 766 (2007).

Hsieh, D. et al. A Topological Dirac Insulator in a Quantum Spin Hall Phase. Nature 452, 970 (2008).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Topological Insulators with Inversion Symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 76, 045302 (2007).

Moore, J. E. & Balents, L. Topological Invariants of Time-Reversal-Invariant Band Structures. Phys. Rev. B 75, 121306(R) (2007).

He, H. T. et al. Impurity Effect on Weak Antilocalization in the Topological Insulator Bi2Te3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 166805 (2011).

Zhang, T. et al. Experimental Demonstration of Topological Surface States Protected by Time-Reversal Symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 266803 (2009).

Hsieh, D. et al. A Tunable Topological Insulator in the Spin Helical Dirac Transport Regime. Nature 460, 1101 (2009).

Murakami, S. Dissipationless Quantum Spin Current at Room Temperature. Science 301, 1348 (2003).

Mellnik, A. R. et al. Spin-Transfer Torque Generated by a Topological Insulator. Nature 511, 449 (2014).

Yokoyama, T. & Murakami, S. Spintronics and Spincaloritronics in Topological Insulators. Phys. E 55, 1 (2014).

Khang, N. H. D., Ueda, Y. & Hai, P. N. A Conductive Topological Insulator with Large Spin Hall Effect for Ultralow Power Spin–Orbit Torque Switching. Nat. Mater. 17, 808 (2018).

Xia, B. et al. Indications of Surface-Dominated Transport in Single Crystalline Nanoflake Devices of Topological Insulator Bi1.5Sb0.5Te1.8Se1.2. Phys. Rev. B 87, 085442 (2013).

Jia, S. et al. Low-Carrier-Concentration Crystals of the Topological Insulator Bi2Te2Se. Phys. Rev. B 84, 235206 (2011).

Ren, Z., Taskin, A. A., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Optimizing Bi2−xSbxTe3−ySey solid solutions to approach the intrinsic topological insulator regime. Phys. Rev. B 84, 165311 (2011).

Ren, Z., Taskin, A. A., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Large Bulk Resistivity and Surface Quantum Oscillations in the Topological Insulator Bi2Te2Se. Phys. Rev. B 82, 241306(R) (2010).

Nakajima, S. The Crystal Structure of Bi2Te3−xSex. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 24, 479 (1963).

Yan, Y. et al. Synthesis and Quantum Transport Properties of Bi Se Topological Insulator Nanostructures. Sci. Rep. 3, 1264 (2013).

Sulaev, A. et al. Electrically Tunable In-Plane Anisotropic Magnetoresistance in Topological Insulator BiSbTeSe2 Nanodevices. Nano Lett. 15, 2061 (2015).

Menshchikova, T. V., Eremeev, S. V., Koroteev, Y. M., Kuznetsov, V. M. & Chulkov, E. V. Ternary Compounds Based on Binary Topological Insulators as an Efficient Way for Modifying the Dirac Cone. JETP Lett. 93, 15 (2011).

Jin, H., Song, J., Freeman, A. J. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Candidates for Topological Insulators: Pb-Based Chalcogenide Series. Phys. Rev. B 83, 041202(R) (2011).

Souma, S. et al. Direct Observation of the Topological Surface States in Lead-Based Ternary Telluride Pb(Bi1-xSbx)2Te4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 116801 (2012).

Kuroda, K. et al. Experimental Verification of PbBi2Te4 as a 3D Topological Insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 206803 (2012).

Ando, Y. Topological Insulator Materials. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 82, 102001 (2013).

Ran, Y., Zhang, Y. & Vishwanath, A. One-Dimensional Topologically Protected Modes in Topological Insulators with Lattice Dislocations. Nat. Phys. 5, 298 (2009).

Imura, K., Takane, Y. & Tanaka, A. Weak Topological Insulator with Protected Gapless Helical States. Phys. Rev. B 84, 035443 (2011).

Hattori, Y., Tokumoto, Y. & Edagawa, K. Optimizing Composition of Pb(Bi1−xSbx)2Te4 topological insulator to achieve a bulk-insulating state. Phys. Rev. Mater. 1, 074201 (2017).

Pan, L., Li, J., Berardan, D. & Dragoe, N. Transport Properties of the SnBi2Te4-PbBi2Te4 Solid Solution. J. Solid State Chem. 225, 168 (2015).

Skinner, B., Chen, T. & Shklovskii, B. I. Why Is the Bulk Resistivity of Topological Insulators so Small? Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 176801 (2012).

Rischau, C. W., Ubaldini, A., Giannini, E. & Beek, C. J. V. Der. Charge Puddles in a Completely Compensated Topological Insulator. New J. Phys. 18, 073024 (2016).

Cech, F. & Vavrin, I. Poubaite, PbBi2(Se,Te,S)4, a New Mineral. Neues Jahrb. für Mineral 1, 9 (1978).

Chatterjee, A., Guin, S. N. & Biswas, K. Ultrathin Septuple Layered PbBi2Se4 Nanosheets. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 14635 (2014).

Shvets, I. A. et al. Impact of stoichiometry and disorder on the electronic structure of the PbBi2Te4−xSex topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B 96, 235124 (2017).

Shelimova, L. E., Karpinskii, O. G. & Zemskov, V. S. X-Ray Diffraction Study of Ternary Layered Compounds in the PbSe-Bi2Se3 System. Inorg. Mater. 44, 927 (2008).

Kimoto, K. et al. Ultramicroscopy Local Crystal Structure Analysis with Several Picometer Precision Using Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy. Ultramicroscopy 110, 778 (2010).

Pennycook, S. & Jesson, D. High-Resolution Incoherent Imaging of Crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 938 (1990).

Yamashita, S. et al. Atomic Number Dependence of Z Contrast in Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy. Sci. Rep. 8, 12325 (2018).

van der Walt, S. et al. Scikit-Image: Image Processing in Python. PeerJ 2, e453 (2014).

Ishizuka, K. Deconvolution Processing in Analytical STEM: Monochromator for EELS and Cs-Corrector for STEM-HAADF. Microsc. Microanal. 11, 1430 (2005).

Kimoto, K. et al. Element-Selective Imaging of Atomic Columns in a Crystal Using STEM and EELS. Nature 450, 702 (2007).

Suenaga, K. et al. Element-Selective Single Atom Imaging. Science. 290, 2280 (2000).

Zheng, Q. et al. Antisite Pairs Suppress the Thermal Conductivity of BAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 105901 (2018).

Scanlon, D. O. et al. Controlling Bulk Conductivity in Topological Insulators: Key Role of Anti-Site Defects. Adv. Mater. 24, 2154 (2012).

Huang, F.-T. et al. Nonstoichiometric Doping and Bi Antisite Defect in Single Crystal Bi2Se3. Phys. Rev. B 86, 081104 (R) (2012).

Knispel, T. et al. Charge Puddles in the Bulk and on the Surface of the Topological Insulator BiSbTeSe2 studied by Scanning Tunneling Microscopy and Optical Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 96, 195135 (2017).

Izumi, F. & Momma, K. Three-Dimensional Visualization in Powder Diffraction. Solid State Phenom 130, 15 (2007).

Jia, S. et al. Defects and High Bulk Resistivities in the Bi-Rich Tetradymite Topological Insulator Bi2+xTe2−xSe. Phys. Rev. B 86, 165119 (2012).

Tobías, G. et al. Anion Ordering and Defect Structure in Ruddlesden-Popper Strontium Niobium Oxynitrides. Inorg. Chem. 43, 8010 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Y. Kamimura of our group for his help in the discussion and the interpretation of the experimental data. We acknowledge Y. Yanaba of IIS, Univ. Tokyo for helpful advices concerning pXRD analyses. This work was financially supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Nos. 19J13968, 18H01692, and 19K04984).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H. designed the study and conducted all the experiments, including sample preparation, X-ray and STEM measurements. Y.T. assisted in designing the experiments. K.K. assisted with the STEM measurements. K.E. supervised the research and contributed in the interpretation of the data. Y.H. wrote the initial manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hattori, Y., Tokumoto, Y., Kimoto, K. et al. Evidences of inner Se ordering in topological insulator PbBi2Te4-PbBi2Se4-PbSb2Se4 solid solutions. Sci Rep 10, 7957 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64742-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64742-6