Abstract

The bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, is a highly migratory and long-living fish at the top of the pelagic food web. As top predator, it plays a key role in the stability of marine food webs by exerting top-down control on its prey. The diet composition of bluefin tuna varies in relation to its growth, seasons and migratory patterns, making it difficult to evaluate spatial and temporal effects. This latter aspect is further complicated to be determined during the first months of life, when T. thynnus specimens have a rapid growth rate leading to changes in the trophic status. In this study, the potential collagen-related effects on δ15N and δ13C values were evaluated on the whole spine of adult tuna specimens collected in the central Mediterranean Sea. Obtained results showed non-significant differences between extracted and non-extracted collagen samples for δ15N in whole spine, allowing adopting the isotopic analysis both for annuli in the spine section of adults and for younger specimens, whose spine size does not permit the collagen extraction. Specifically, isotopic analysis of whole spine of the young of the year specimens, showed a rapid change in δ15N values with length, following an exponential model. For older specimens, δ15N values were higher and varied around a plateau, likely due to a higher specificity in the choice of prey and/or to change in the geographical location. Such variability was also mirrored in annuli of spines sections of adult tunas. As far as δ13C values are concerned, a strong collagen-related effect was evidenced, likely highlighting the influence of lipids. Consequently, δ13C analysis may be used only on adult specimens where collagen extraction is possible. This research also showed how isotopic analysis of both whole sample and sequence of annuli in the cross-section of dorsal spine might produce isotopic profiles useful to detect specific trophic dynamics along the bluefin tuna growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, stable nitrogen and carbon isotopes analyses (δ15N and δ13C), performed on less metabolically active tissues, such as scale, otoliths, spines and bones, allowed to investigate several aspects of animal’s feeding habits, habitat use and migration (e.g. 1,2,3,4,5,6). However, there are different isotopic approaches for estimating diet and movement patterns of multiple taxa using inert tissues. For instance, the collagen extracted from whole bone of an animal can provide an integration of stable isotopes from multiple years with a general interpretation of its trophic behavior during the entire lifetime2,7,8,9,10,11. The analysis in single layers in some hard structures, such as teeth and humerus (with each layer representing a different interval of animal’s life), provides a time series of isotopic data, useful for reconstructing an animal’s foraging ecology over time7,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. It is important to single out that some methods need large amount of sample in order to remove lipids and other contaminants (e.g. collagen extraction), thus preventing their use for samples characterized by small dimensions14; other methods require a greater efficiency and accuracy in the determination and in the selection of individual annual growth layer from the tissue section (e.g. skeletochronology method)14,15,16.

The present study proposes a method able to estimate stable isotope values in metabolically non-active tissues (with a life history memory), verifying if it could be used also when the amount of sample material is not enough to perform the traditional collagen extraction procedure, (such as in very small fish species, in archaeological remains or in hard tissues of species stored in museums).

The isotopic analysis was here applied on the first dorsal spine of both adults and young of the year (YOY) bluefin tuna specimens, caught in the central Mediterranean Sea, to address important questions on the ecology and feeding behaviour of this species during its growth. Spine sections of adult tuna, often chosen for growth studies (e.g.20), were also considered to combine isotopic results with growth layers.

The bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, is a highly migratory and long-living fish at the top of the pelagic food web and plays a key role in the stability of marine food webs by exerting top-down control on its prey21. It feeds on a broad spectrum of prey items, such as small pelagic fish, cephalopods and shrimps22,23,24,25; furthermore, in some Mediterranean and Atlantic feeding grounds, the component of mesopelagic fish is dominant in its diet26,27. However, the diet composition of bluefin tuna varies in relation to its growth, seasons and migratory patterns, making it difficult to evaluate spatial and temporal effects. This latter aspect is further complicated during the first months of life, when T. thynnus specimens have a rapid growth rate leading to changes in its trophic status. Moreover, the Reg. CE 302/2009 prohibits fishing tuna specimens of size smaller than 115 cm (specimen weight <30 kg), making the trophic position in the early life stage difficult to be determined.

In the present study, stable nitrogen and carbon isotopes (δ15N and δ13C) values and elemental nitrogen (%N) and carbon (%C) composition were obtained from: (1) extracted and non-extracted collagen samples obtained from the same spines of bluefin tuna adults, in order to evaluate the possible differences in the isotopic values between the two approaches; (2) whole spine of both YOY and adults tuna (without collagen extraction), to highlight differences in feeding behavior between the two macro-size classes (YOY and Juveniles/Adults); (3) untreated micromilled powder obtained from individual growth layers of spine section, to provide a more detailed trophic ecology in each layer representing a different period of animal’s stage.

Results

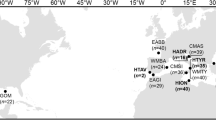

A total of 51 T. thynnus specimens were collected in two sampling sites (Fig. 1): 29 Juveniles/Adults (with fork length FL > 50 cm) and 22 young of the year (YOY with FL < 50 cm) tuna. Ages of the specimens ranged between the first year of life to fifteen years (Table 1).

Study area with sampling locations (Map generated by using the QGis 2.8 - https://qgis.org/).

Paired Wilcoxon test, carried out on δ15N and δ13C values obtained on extracted and non-extracted collagen samples of 28 Juveniles/Adults tunas (Fig. 2), showed non-significant differences for δ15N values, while a significant difference was observed for δ13C (W = 0, p-value = 7.451e-09). Mean δ13C values of non-extracted collagen was 4.8‰ lower than the same extracted collagen samples (Fig. 2).

Boxplot of δ13C and δ15N values from spines of Thunnus thynnus. Top panels report the boxplots only for samples where it was possible to replicate the isotopic analyses on both extracted and non-extracted samples. Bottom panels boxplot compares the isotopic values between Adults/Juveniles (A/J) and young of the year (YOY) considering only non-extracted samples.

Looking at differences between YOY and Juveniles/Adults (only for non-extracted collagen samples), significant differences were found in terms of δ15N (W = 55, p-value = 5.384e-07), while non-significant difference was evidenced for δ13C values. In particular, δ15N values were higher in Juveniles/Adults specimens than in YOY, with absolute differences in median values of 1.4‰ (see Fig. 2). Finally, when δ15N and δ13C values were compared among core, non-opaque and opaque bands in spines section, non-significant differences were found in terms of δ15N, while significant differences were observed for δ13C. In particular, a Tukey HSD post-hoc test highlighted that δ13C values in the core were significantly lower (p < 0.05) than the ones recorded in non-opaque and opaque bands, while non-significant differences were identified between these latter categories (Fig. 3).

In order to better characterize the change in δ15N values due to growth, δ15N values were fitted according to the exponential model (Fig. 4), the estimated parameters “a” and “b” were found to be 7.56‰ and 26.75 cm respectively (Table 2). In this context, the “a” parameter represents the δ15N plateau value, while the “b” one represents the 1/3 of the FL value where the plateau is reached. Thus, according to the fitted model, the plateau was reached at around 80 cm (FL).

Discussion and conclusions

In isotopic studies focusing on hard tissues, a large amount of material is needed to carry out the collagen extraction in order to obtain reliable information on isotopes values14. In this study, we compared the results of isotopic analysis on dorsal spines of Bluefin tuna in order to support the adoption of isotopic analysis also when the amount of sample material is not enough to perform the traditional collagen extraction. Specifically, the non-significant difference between δ15N values obtained from extracted and non-extracted collagen samples permitted the direct determination of δ15N on whole spine of both YOY and Juveniles/Adults, and on milled bone powder (obtained from growth layer of a section spine).

δ15N values in consumer tissues are driven not only by trophic position of their prey, but are also strongly influenced by the baseline for δ15N (i.e. that of primary producers), which has a strong geographic variation28,29. In this study, we assumed that the YOY tuna, collected from north-eastern Sicily, were likely too young to have migrated in other sites30 and were assumed to have consumed their prey where they were caught. In this way, we did not consider the spatial effects on the δ15N values for smaller individuals. In this context, it is worth noting that YOY observations are quite close to the curve obtained by fitting the exponential model using δ15N and FL values (Fig. 4). On the contrary, adults’ δ15N values showed high dispersion around the plateau, evidencing a clear spatial effect (i.e. the observed higher variability could be likely due to changes in prey items reflecting higher migratory capability of adults, leading them to explore different areas in a relatively short time interval). Thus, assuming the lack of a spatial effect for YOY, the rapid increase of δ15N values in the size range 17–48 cm FL was likely linked to the trophic status of the consumed prey that changes quickly during the period of rapid growth for bluefin tuna (e.g. 21,31,32). In the first life stages (FL in the range 17–48 cm), the low δ15N values (mean 5.1 ± 1.4‰) recorded in the YOY tuna specimens may be due to a diet starting on planktonic copepods and euphausiids, that could provide a high-energy food source for juvenile bluefin tuna during periods of rapid growth, and subsequently on small cephalopods22,30,31,33,34. Zooplankton may represent an overlooked prey base for YOY bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean Sea but information on the diet of such early juveniles is scanty (e.g. 22,30). Moreover, at the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the relationship between δ15N values and Fork Length (FL) in the Young Of Year (YOY) bluefin tuna. Our data clearly evidenced a continuous increase of δ15N values with growth. The comparison between the dynamics of trophic shift in BFT and the one observed in Thunnus albacares evidenced strong differences mainly for smaller specimens. Weng et al. (2015) and Graham et al. (2007) reported a sigmoid relationship between δ15N values and FL, thus smaller yellowfin tuna (FL range 20–40 cm) showed an almost constant δ15N values up to FLs > 40 cm. For this species, the diet shift was very rapid and the δ15N plateau was reached between 40 and 50 cm. The δ15N values of bluefin tuna YOY (in this study) were characterized by a continuous increase up to 80 cm (FL). We believe that this difference between the two species could be linked to different factors such as: 1) the same prey in different waters may exhibit different stable isotopes values due to differences in the nutrient sources that affect the N values of food webs; 2) differences in physiology and development (e.g. differences in the development of gape size); 3) differences in feeding strategies and/or prey selectivity.

On the other hand, the high variability found in δ15N values of Juveniles/Adults bluefin tuna suggested that for tuna with FL > 50 cm diet passes to be based mainly on cephalopods and fish21,30. Furthermore, this variability may be affected by geographical location of prey and by different prey assemblages. Indeed, during migration, from spawning locations to feeding grounds, bluefin tuna probably fed as they encountered patches of prey26 but it will be also possible that groups of migratory bluefin tuna stop to feed at unidentified locations during seasonal migrations (e.g. 21). The high variability of δ15N values in Juveniles/Adults specimens was also shown when the isotopic values, related to consecutive opaque and hyaline bands, were considered (Fig. 5).

When direct determination of δ15N was obtained on powder micromilled growth layers of spine of adults bluefin tuna, the amount of material did not permit to determine elemental composition of nitrogen (and consequently of C:N ratios), inhibiting also the evaluation of lipids effects in the growth layers.

The significant differences in δ13C values, observed by comparing isotopic values from extracted and non-extracted collagen from spines of Juveniles/Adults tuna, is due to the presence of lipids and bioapatite that can enrich or deplete these values, respectively. Despite sub-samples of spines were subject to acidification with HCl before the isotopic analysis and no effect was recorded during this process, we assumed that the effect of bioapatite on δ13C values could be negligible in our samples, in agreement to16. On the contrary, the δ13C values, lower in non-extracted collagen samples, evidenced the presence of lipid-bond carbon. Lipids are generally 2–3‰ more depleted in 13C than in other organic molecules35,36. Moreover, also when direct determination of δ13C values was obtained on powder micromilled growth layers of spine of adults bluefin tuna, Tukey HSD post-hoc test highlighted that δ13C values in the core were significantly lower (p < 0.05) than the ones recorded in the growth layers. Consequently, we recommend to consider only samples that fall in the C:N range 2.6–3.536 to confirm that lipid extraction is not necessary. Since C:N ratio was not always determinable in untreated samples and, to our knowledge, no standard protocol for δ13C correction exists for T. thynnus, in this work we decided to use only the δ15N values to produce a time series of stable isotope patterns from individual animals. Indeed, both acidification and lipids removal should affect only bioapatite carbon and not collagen-bound nitrogen. Furthermore, the lipid molecules do not contain nitrogen16.

However, supplementary researches are needed to establish if the lipids effects are linked only to the inner medullary cavity or also to the different growth layers, especially for the case in which the C:N is difficult to determine due to samples material derived from drilled growth layers. Unfortunately, with our current knowledge, we are not able to evaluate this aspect. We postpone to future studies the possibility to find a method (or an equation) that will allow the correction of the lipids effects of δ13C values from untreated and not delipidated samples (whole spine and/or powder extracted from growth layers) for this species. However, the obtained results evidenced that the δ15N analysis can be used to produce isotopic profiles useful to detect trophic and foraging habitat changes along the individual lifetime, particularly when the amount of sample material is not enough to perform the collagen extraction, such as in small fish, archeological remains (mainly fish remains) and/or spines of fish stored in the museum (extinct species or in need of conservation).

Materials and Methods

Sample collection and processing

Bluefin tuna specimens were collected in two sampling sites located in the north-western and north-eastern Sicily (Italy), respectively (Fig. 1). No use of live animals was made in this study. Samples have been collected within a National Project funded by MIPAF (“Valuation of the ecotoxicology impacts from old and new contaminants, study of biology and ecology of the Mediterranean population of swordfish, bluefin tuna and albacore” cod. 6A108) and additional samples were obtained by Maritime Authority during the bluefin tuna landings in the designated port of Milazzo (ICCAT List Number 849). Sampling site and date, fork length (FL) and weight of the fish specimens were recorded (Table 1). Taxonomic identification of individuals was done examining the morphological and meristic features in accordance with key characters reported by37,38.

Dorsal fin spines were extracted and frozen prior to laboratory processing. For each tuna specimen, both the first dorsal spine (to determine δ15N and δ13C values) and the otoliths for age determination were extracted. After thawing, fin spines were cleaned of epidermal and dermal tissue and washed thoroughly with double-distilled water. The age of each specimen was determined by reading the growth increments in the otoliths, according to39. The laboratory analyses were performed following the work scheme showed in Fig. 6.

The work scheme of laboratory analysis. (1) Collagen extraction: (a) extraction of first dorsal spine; (b) pieces of spine; (c,d) preparation to collagen extraction; (e) example of collagen extracted. (2) Analysis of whole spine: (a) spine; (b) steps to obtain powder of spine. (3) Powder of Opaque and Non-opaque bands: (a) section of the spine; (b) binocular to drilled the bands; (c) small drill; (d) powder obtained. (4) Weight in tin cups. (5) ThermoFisher Flash EA1112 elemental analyzer coupled to a Thermo Electron Delta Plus XP isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS). (Thunnus thynnus picture permission granted by the author Andrea Paoli).

Collagen extraction

Collagen was extracted from samples of Juveniles/Adults tuna through revised protocols used for fish bones9,11. In particular, for each specimen, the whole spine (having an average mass between 150 and 200 mg) was placed in a test-tube and 10 ml of 0.2 M HCl was added. The spine pieces were left for 24–48 h to demineralize at 5 °C. Demineralized residues were soaked overnight in 0.125 NaOH to remove lipids and other contaminants. These were then rinsed repeatedly in the filter funnel. Using a water bath, remaining residues were heated in centrifuge tubes for 10 h in a dilute HCl solution (pH~3) at 90–95 °C to solubilize collagen9,40. Finally, the remaining solution was concentrated on the ultra-filters by centrifugation at 2500 rpm. The supernatant of purified “collagen” was dried for 48 h, crushed and weighted (~0.5 mg) in tin cups.

Whole spines and annuli sections

Whole spines of both YOY and Juveniles/Adults tuna were pulverized with mortar and pestle. Collagen and lipids were not removed from spines prior to isotope analysis. However, sub-sample of whole spine was subject to acidification (with 0.25 M HCl) to test the carbonate presence16. Additionally, growth layers of 7 sections of Juveniles/Adults tuna were also used for isotopic analysis. Opaque and non-opaque bands in otolith section were drilled with a small hand–held drill (Black&Deker RT650) under a binocular (Leica MZ6) and the obtained powder (~0.2 mg - 0.4 mg) was directly load in tin cups for isotopic analysis. The core of the section spine was also isotopically analyzed.

Collagen samples, whole spines (without collagen extraction), powder of opaque and non-opaque bands (untreated) were analysed with a ThermoFisher Flash EA 1112 elemental analyzer coupled to a Thermo Electron Delta Plus XP isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) at the Geochemistry Laboratory of the CNR Institute in Naples (Italy). Samples were run against blank cups and known urea standards (analytical grade urea of certificated isotopic composition) and IAEA international standard (IAEA N-1 and IAEA CH-7). Three capsules of urea were analysed at the beginning of each sequence. Moreover, one capsule of urea was analysed every six samples, in order to compensate for potential machine drift and as a quality control measure41. Experimental precision (based on the standard deviation of replicates of the internal standard) was <0.2‰ for δ15N and <0.1‰ for δ13C.

δ13C and δ15N values were obtained in parts per thousand (‰) relative to Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (vPDB) and atmospheric N2 standards, respectively, according to the following formula:

Results of isotopic values (δ13C and δ15N) are reported in Table 1. Where possible, replicates of analytical procedures and replicates of the same samples were performed. The standard deviation for each approach is also reported in Table 1.

When the percentage of total nitrogen (%N) was sufficient, C:N ratio was directly determined from isotopic analysis through the Elemental Analyzer using Acetanilide standard (C8H9ON, elemental composition: 71.09% carbon and 10.36% nitrogen).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out by using R statistical environment (R Core Team, 2019). Statistical tests were used in order to verify if observed differences in terms of δ15N and δ13C between considered groups (collagen extracted vs non-extracted samples) were statistically significant. A preliminary check for normality and homogeneity of variances was carried out in order to verify the basic assumptions required by parametric t-test. If homogeneity of variances assumption was not met, the Welch t-test was used42, while, if normality assumption was not met, the non-parametric alternative t-test (i.e. the Wilcoxon tests) was adopted. When the number of groups was more than two, requiring then an ANOVA test, the same approach was adopted to check for normality and homogeneity of variances. If such assumptions were not met, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was used.

The relationship between δ15N values and FL was also investigated. In particular, the following exponential model was adopted:

The parameters estimate was performed by means of nonlinear (weighted) least-squares estimates by using the “nls2”43 package.

The FL value linked to each age was computed by means of the following age-length relationship44:

The nitrogen isotopic values at time t (δt) or at the time t-1 (δt−1) were also evaluated considering the isotopic mean of two consecutive bands (opaque and hyaline).

References

Jessop, B. M., Shiao, J., Iizuka, Y. & Tzeng, W. Migratory behaviour and habitat use by American eels Anguilla rostrata as revealed by otolith microchemistry. 233, 217–229 (2002).

Newsome, S. D., Clementz, M. T. & Koch, P. L. Using stable isotope biogeochemistry to study marine mammal ecology. Mar. Mammal Sci. 26, 509–572 (2010).

Clementz, M. T. & Koch, P. L. Differentiating aquatic mammal habitat and foraging ecology with stable isotopes in tooth enamel. Oecologia 129, 461–472 (2001).

Zanden, H. B. V., Bjorndal, K. A., Reich, K. J. & Bolten, A. B. Individual specialists in a generalist population: Results from a long-term stable isotope series. Biol. Lett. 6, 711–714 (2010).

Avens, L. et al. Complementary skeletochronology and stable isotope analyses offer new insight into juvenile loggerhead sea turtle oceanic stage duration and growth dynamics. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 491, 235–251 (2013).

Carlisle, A. B. et al. Using stable isotope analysis to understand the migration and trophic ecology of northeastern Pacific white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias). PLoS One 7 (2012).

Deniro, M. J. & Epstein, S. Influence of diet on the distribution of nitrogen isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 45, 341–351 (1980).

Koch, P. L. Isotopic study of the biology of modern and fossil vertebrates. in Stable isotopes in ecology and environmental science. (Blackwell Publishing, Boston, MA., 2007).

Ambrose, S. H. Preparation and characterization of bone and tooth collagen for isotopic analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 17, 431–451 (1990).

Chisholm, B. S., Nelson, D. E., Hobson, K. A., Schwarcz, H. P. & Knyf, M. Carbon isotope measurement techniques for bone collagen. J. Archaeol. Sci. 10, 355–360 (1983).

Jørkov, M. L. S., Heinemeier, J. & Lynnerup, N. Evaluating bone collagen extraction methods for stable isotope analysis in dietary studies. J. Archaeol. Sci. 34, 1824–1829 (2007).

Snover, M. L., Hohn, A. A., Crowder, L. B. & Macko, S. A. Combining stable isotopes and skeletal growth marks to detect habitat shifts in juvenile loggerhead sea turtles Caretta caretta. Endanger. Species Res. 13, 25–31 (2010).

Elorriaga-Verplancken, F., Aurioles-Gamboa, D., Newsome, S. D. & Martínez-Díaz, S. F. δ15N and δ13C values in dental collagen as a proxy for age- and sex-related variation in foraging strategies of California sea lions. Mar. Biol. 160, 641–652 (2013).

Turner Tomaszewicz, C. N., Seminoff, J. A., Avens, L. & Kurle, C. M. Methods for sampling sequential annual bone growth layers for stable isotope analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 556–564 (2016).

Turner Tomaszewicz, C. N., Seminoff, J. A., Peckham, S. H., Avens, L. & Kurle, C. M. Intrapopulation variability in the timing of ontogenetic habitat shifts in sea turtles revealed using δ15N values from bone growth rings. J. Anim. Ecol. 86, 694–704 (2017).

Turner Tomaszewicz, C. N., Seminoff, J. A. & Rairez D. Matthew, K. C. M. HHS Public Access. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 29, 1879–1888 (2015).

Campana, S. E. Accuracy, precision and quality control in age determination, including a review of the use and abuse of age validation methods. J. Fish Biol. 59, 197–242 (2001).

Schoeninger, M. J. & DeNiro, M. J. Nitrogen and carbon isotopic composition of bone collagen from marine and terrestrial animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 48, 625–639 (1984).

Tieszen, L. L., Boutton, T. W., Tesdahl, K. G. & Slade, N. A. Fractionation and turnover of stable carbon isotopes in animal tissues: Implications for δ13C analysis of diet. Oecologia 57, 32–37 (1983).

Megalofonou, P. & de Metrio, G. Age estimation and annulus-formation in dorsal spines of juvenile bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, from the Mediterranean Sea. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom 80, 753–754 (2000).

Estrada, J. A., Lutcavage, M. & Thorrold, S. R. Diet and trophic position of Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) inferred from stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis. Mar. Biol. 147, 37–45 (2005).

Battaglia, P., Pedà, C., Sinopoli, M., Romeo, T. & Andaloro, F. Cephalopods in the diet of young-of-the-year bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus L. 1758, Pisces: Scombridae) from the southern Tyrrhenian Sea (central Mediterranean Sea). Ital. J. Zool. 80, 560–565 (2013).

Chase, B. C. Differences in diet of Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) at five seasonal feeding grounds on the New England continental shelf. Fish. Bull. 100, 168–180 (2002).

Karakulak, F. S., Salman, A. & Oray, I. K. Diet composition of bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus L. 1758) in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea, Turkey. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 25, 757–761 (2009).

Logan, J. M. et al. Diet of young Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) in eastern and western Atlantic foraging grounds. Mar. Biol. 158, 73–85 (2011).

Battaglia, P. et al. Feeding habits of the Atlantic bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus (L. 1758), in the central Mediterranean Sea (Strait of Messina). Helgol. Mar. Res. 67, 97–107 (2013).

Olafsdottir, D. et al. Dietary Evidence of Mesopelagic and Pelagic Foraging by Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus thynnus L.) during Autumn Migrations to the Iceland Basin. Front. Mar. Sci. 100, 168–180 (2016).

Seminoff, J. A. et al. Stable isotope tracking of endangered sea turtles: validation with satellite telemetry and δ15N analysis of amino acids. PLoS One 7, e37403 (2012).

Hart, K. M. et al. Determining origin in a migratory marine vertebrate: a novel method to integrate stable isotopes and satellite tracking. Ecol. Appl. 25, 320–335 (2014).

Sinopoli, M. et al. Diet of young-of-the-year bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus (Linnaeus, 1758), in the southern Tyrrhenian (Mediterranean) Sea. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 20, 310–313 (2004).

Graham, B. S., Grubbs, D., Holland, K. & Popp, B. N. A rapid ontogenetic shift in the diet of juvenile yellowfin tuna from Hawaii. Mar. Biol. 150, 647–658 (2007).

Kitagawa, T. & Fujioka, K. Rapid ontogenetic shift in juvenile Pacific bluefin tuna diet. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 571, 253–257 (2017).

Logan, J. M. Tracking diet and movement of Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) using carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes Submitted to the University. (2014).

Laiz-Carrion, R. et al. Larval bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) trophodynamics from Balearic sea (WM) and gulf of Mexico spawning ecosystems by stable isotope. Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT 71(3), 1354–1365 (2015).

DeNiro, M. J. & Epstein, S. Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 52, 1597–1599 (2010).

Post, D. M. et al. Getting to the fat of the matter: Models, methods and assumptions for dealing with lipids in stable isotope analyses. Oecologia 152, 179–189 (2007).

Collette, B. B. & Nauen, C. E. FAO Species Catalogue Vol. 2 Scombrids of the world an annotated and illustrated catalogue of Tunas, Mackerels, Bonitos and related species know to date. FAO Fisheries Synopsis 2 (1983).

Collette, B. Fishes of the north-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean. (1986).

Cort, J. L. Age and growth of the blue¢n tuna, Thunnus thynnus (L.) of the northeast Atlantic. ICCAT, Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. 35, 213–230 (1991).

Reitsema, L. J., Crews, D. E. & Polcyn, M. Preliminary evidence for medieval Polish diet from carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes. J. Archaeol. Sci. 37, 1413–1423 (2010).

Rumolo, P. et al. Linking spatial distribution and feeding behavior of Atlantic horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) in the Strait of Sicily (Central Mediterranean Sea). J. Sea Res. 121, 47–58 (2017).

Welch, B. L. The generalization of ‘Student’s’ problem when several different population variances are involved. Biometrika 34, 28–35 (1947).

Grothendieck, G. nls2: Non-linear regression with brute force. R package version 0.2. (2013).

Santamaria, N. et al. Age and growth of Atlantic bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus (Osteichthyes: Thunnidae), in the Mediterranean Sea. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 25, 38–45 (2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.P. conceived the work, performed experiment and isotopic analysis in Geochemical lab; contributed to the organization of the manuscript; wrote the main manuscript text.B.M. performed statistical analysis; contributed and wrote the manuscript; prepared Figures 1–6 and Tables 1–2. Genovese Simona participated to sampling; performed the lab analysis. R.T. participated to sampling; contributed to the organization of manuscript. M.S. contributed to the organization of manuscript. B.G. participated to sampling. Gherardi Serena performed lab and isotopic analysis. B.P. participated to sampling. A.F. participated to sampling, contributed to the organization of manuscript. B.A. contributed to the organization of manuscript and wrote the main manuscript text. In different way, all the authors contributed to paper writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rumolo, P., Bonanno, A., Genovese, S. et al. Growth-related trophic changes of Thunnus thynnus as evidenced by stable nitrogen isotopic values in the first dorsal spine. Sci Rep 10, 9899 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66566-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66566-w