Abstract

Bimodal classification of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis (ICP) into early-onset (<35 years) and late-onset (>35 years) ICP was proposed in 1994 based on a study of 66 patients. However, bimodal distribution wasn’t sufficiently demonstrated. Our objective was to examine the validity and relevance of the age-based bimodal classification of ICP. We analyzed the distribution of age at onset of ICP in our cohort of 1633 patients admitted to our center from January 2000 to December 2013. Classify ICP patients into early-onset ICP(a) and late-onset ICP(a) according to different cut-off values (cut-off value, a = 15, 25, 35, 45, 55, 65 years old) for age at onset. Compare clinical characteristics of early-onset ICP(a) and late-onset ICP(a). We found slightly right skewed distribution of age at onset for ICP in our cohort. There were differences between early-onset and late-onset ICP with respect to basic clinical characteristics and development of key clinical events regardless of the cut off age at onset i.e. 15, 25, 35, 45 or even higher. The validity of the bimodal classification of early-onset and late-onset ICP could not be established in our large patient cohort and therefore such a classification needs to be reconsidered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Idiopathic chronic pancreatitis (ICP) has traditionally been defined as chronic pancreatitis (CP) in the absence of any obvious precipitating factors (e.g. alcohol abuse) and family history of the disease. In 1994, Layer et al. found distribution of the age at onset of ICP was bimodal1. According to bimodal phenomenon, they defined patients with age at onset of ICP < 35 years as early-onset ICP (EOICP) and those with age at onset of ICP > 35 years as late-onset ICP (LOICP)1.

Throughout these years, the classification was applied widely as a standard classification2. Several studies have found differences between EOICP and LOICP. It’s reported that EOICP patients have more severe pain1,3. Diabetes and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency were less frequent presenting symptoms in EOICP1,3. No significant difference was seen regarding pancreatic calcification between EOICP and LOICP4.

To our knowledge, no study has validated the distribution of age at onset of ICP after Layer et al. Bimodal distribution has never been shown by subsequent studies. For studies exhibiting age at onset of ICP, the distribution of age at onset of ICP was either not shown or shown as normal distribution (Table 1)1,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Bimodal phenomenon was proposed based on a small sample study with only 66 ICP patients. Moreover, this distribution wasn’t statistically tested1. Thus, the distribution of age at onset of ICP remained to be explored.

Our objective was to correlate the age at onset of CP with disease course in order to examine the validity and relevance of the age-based bimodal classification of CP. In addition, we re-analyzed the age distribution of the study by Layer et al. which had suggested a bimodal age distribution.

Materials and Methods

Patients and database

Patients were from Changhai CP Database in which patients were retrospectively and prospectively enrolled. The detailed information of Changhai CP Database (version number 2.1, Shanghai, China) has been reported in our previous researches15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. The exclusion criteria were as follows: pancreatic cancer diagnosed within 2 years after the diagnosis of CP23, groove pancreatitis24, autoimmune pancreatitis, and CP patients with distinct etiologies (including alcoholic, abnormal anatomy of pancreatic duct, hereditary, post-traumatic, and hyperlipidemic). All of the ICP patients in our database16,18 were enrolled in this study. All of the diagnostic modalities were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. All ICP patients were treated according to guidelines25,26,27.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Changhai Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients. Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination of this research. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Definitions of ICP and key clinical events in clinical course

Diagnosis of CP was established according to Asia-Pacific consensus28. The detailed diagnostic criteria of alcoholic CP, hereditary CP, post-traumatic CP, CP caused by hyperlipidemia, CP caused by abnormal anatomy of the pancreatic duct and ICP were described in our previous series reports17,29. The key clinical events of CP in clinical course included DM, steatorrhea, biliary stricture, pancreatic pseudocyst (PPC), pancreatic stones and pancreatic cancer. Diagnosis of DM was based on the criteria of the American Diabetes Association30. Diagnosis of steatorrhea was established when either of the following conditions was met: (1) chronic diarrhea with foul-smelling, oily bowel movements31; (2) a positive result in quantification of fecal fat determination (fecal fat quantification was performed over a period of three days; steatorrhea was defined as a fecal fat excretion of more than 14 g/day. Biliary stricture was defined as a narrowing of the biliary stricture with prestenosis dilation >1 cm on magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, or ultrasound, or delayed runoff of contrast on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography32. Diagnosis of PPC, pancreatic stones and pancreatic cancer was established according to guidelines33,34,35,36.

Categories

CP with the age at onset of disease <35 years was defined as EOICP and those>35 was defined as LOICP according to Layer’s study1. To explore the uniqueness of Layer et al.’s classification, other cut-off values (a) for age at onset of ICP were selected as the new standard to classify EOICPa and LOICPa by increasing or decreasing the original cut-off value (35) by every 10 years. Thus, cut-off values, a (15, 25, 35, 45, 55, 65) were selected. Patients with the age at onset of ICP younger than the cut-off value were defined as EOICPa and those with the age at onset of ICP older than the cut-off value were defined as LOICPa.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the median (interquartile ranges) and were compared using an unpaired, 2-tailed t test for normally distributed data or the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to identify description of age at onset of ICP via SPSS (version 23.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Distribution of age at onset of ICP in Layer’s population and in our database was explored separately via Cullen and Frey graph drew from fitdistrplus package of R [version 3.5.0 (http://www.r-project.org/)] and Individual Distribution Identification together with Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function in Minitab software [version 18 (http://www.minitab.com/zh-cn/)]. The cumulative rates of key clinical events after the onset of ICP were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between EOICPa and LOICPa were compared using Log-Rank test.

Results

Distribution of age at onset of ICP

Totally there were 1,633 ICP patients in our study and the baseline clinical and demographic data was exhibited in Supplementary Table 1. The median duration of follow-up was 9.8 (0.1, 53.2) years for all these 1,633 ICP patients. Bar graph for the distribution of age at onset of ICP was presented (Fig. 1A).

Distribution of age at onset of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. (A) Distribution of age at onset of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in our study. (B) Distribution of reconstructed data of age at onset of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in Layer et al.’s study. ICP = idiopathic chronic pancreatitis.

For ICP population in our study, Cullen and Frey graph revealed the distribution was not identical to uniform distribution or normal distribution (Fig. 2A). Further analysis showed there was right skewed distribution of the age at the onset of ICP with the skewness of 0.05 and the kurtosis of 2.33 calculated by R. The median age at onset of ICP was 38.21 years and mean age was 38.05 years (Supplementary Table 2). This skewed distribution was close to normal distribution which could be figured out through the empirical cumulative distribution function (Fig. 2C). Probability plot and empirical cumulative distribution function plot revealed there was no other satisfying distributions for age at onset of ICP in other thirteen classic distributions (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Table 4).

Distribution of age at onset of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. (A) Cullen and Frey graph of distribution of age at onset of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in our study. The blue dot (observation) was near the marker of normal distribution and uniform distribution but not overlaying the markers of them. (B) Cullen and Frey graph of distribution of age at onset of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in Layer et al.’s study (calculated with reconstructed data). The blue dot (observation) was very close to the marker of uniform distribution. (C) Empirical cumulative distribution function for age at onset of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in our study. (D) Empirical cumulative distribution function for age at onset of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in Layer et al.’s study (calculated with reconstructed data). ICP = idiopathic chronic pancreatitis; CDF = empirical cumulative distribution function.

There were 66 ICP patients in Layer et al.’s study. The age at onset of ICP were reconstructed (Fig. 1B). Cullen and Frey graph revealed the distribution of Layer et al.’s population was nearly uniform distribution and it was far away from normal distribution (Fig. 2B). The empirical cumulative distribution function showed the distribution was not normal distribution (Fig. 2D). Kolmogorov–Smirnov test further verified that it was definitely uniform distribution (Supplementary Table 5, P = 0.224).

General comparison of EOICPa and LOICPa with different cut-off values

When ICP patents were classified with distinct cut-offs, great differences were still observed between EOICPa and LOICPa (Table 2). Abdominal pain was dominant in initial manifestations and had higher proportion in EOICPa than LOICPa in the six classifications (P < 0.01). In the entire course of ICP, ratio of patients without pain was higher in LOICPa than EOICPa (when cut-off value equals 15, 25, 35, 45, 55: P < 0.001).

Pancreatic stones present higher proportion in EOICPa than LOICPa (P < 0.001). DM was found more frequently in LOICPa than EOICPa when cut-off value equals 15, 25, 35, 45 (P < 0.001), but the results were opposite when ICP patients were divided by 55 and 65 cutoffs with no significance. Steatorrhea was found more frequently in LOICPa than EOICPa when cut-off value equals 15 (P < 0.001) and 25 (P > 0.05) but the results were opposite when ICP patients were divided by 45, 55 and 65 cutoffs (all P < 0.05). Proportion of biliary stricture was higher in LOICPa than EOICPa (all P < 0.001). Proportion of PPC was higher in LOICPa than EOICPa (when cut-off value equals 15, 25, P < 0.05). Pancreatic cancer was more common in LOICPa than EOICPa when cut-off value equals 35 and 45 (P < 0.05). Death was more common in LOICPa than EOICPa in all the comparisons (P < 0.01).

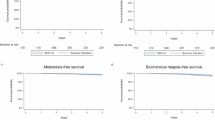

Comparisons of cumulative rates of key clinical events in EOICPa and LOICPa

Significant difference in the cumulative rates of DM after the onset of ICP was observed between EOICPa and LOICPa patients when the cut-off values were 15, 25, 35, 45, 55 (P < 0.05, Fig. 3A). Significant difference in the cumulative rates of steatorrhea after the onset of ICP was observed between EOICPa and LOICPa patients when the cut-off values were 15, 25, 35, 65 (P < 0.05, Fig. 3B). Significant difference in the cumulative rates of biliary stricture after the onset of ICP was observed between EOICPa and LOICPa patients when the cut-off values were 15, 25, 35, 45, 55, 65 (P < 0.001, Fig. 3C). Significant difference in the cumulative rates of PPC after the onset of ICP was observed between EOICPa and LOICPa patients when the cut-off values were 15, 25, 35, 45, 65 (P < 0.01, Fig. 3D). Significant difference in the cumulative rates of pancreatic stones after the onset of ICP was observed between EOICPa and LOICPa patients when the cut-off values were 45, 65 (P < 0.05, Fig. 3E). Significant difference in the cumulative rates of pancreatic cancer after the onset of ICP was observed between EOICPa and LOICPa patients when the cut-off values were 35, 45 (P < 0.01, Fig. 3F).

The cumulative rates after the onset of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. (A) The cumulative rates of diabetes mellitus; (B) The cumulative rates of steatorrhea; (C) The cumulative rates of biliary stricture; (D) The cumulative rates of pancreatic pseudocyst; (E) The cumulative rates of pancreatic stone; (F) The cumulative rates of pancreatic cancer. The letter a, b, c, d, e and f refer to the zero point of the curve for different cut-off values. DM = diabetes mellitus, ICP = idiopathic chronic pancreatitis, PPC = pancreatic pseudocyst ***Significant in comparison of cumulative rates in early-onset idiopathic chronic pancreatitis(a) (EOICPa) and late-onset idiopathic chronic pancreatitis(a) (LOICPa) at P < 0.001. **Significant in comparison of cumulative rates in EOICPa and LOICPa at P < 0.01. *Significant in comparison of cumulative rates in EOICPa and LOICPa at P < 0.05. NS: No significance in comparison of cumulative rates in EOICPa and LOICPa.

Discussion

To our previous knowledge, EOICP and LOICP were identified as two different entities due to the two distinct age groups of ICP patients. However, the bimodal distribution of age at onset of ICP was proposed based on a small sample and the distribution wasn’t statistically tested. Through our analysis, the distribution of reconstructed data for age at the onset of ICP patients in Layer et al.’s study turned out to be a uniform distribution rather than a bimodal distribution1. The existence of key clinical events and differences always exist no matter what the cut-off value is for EOICPa and LOICPa. Therefore, the classification of EOICP and LOICP by Layer et al. needs to be reconsidered.

When classifying ICP patients with different cut-off values for the age at onset of ICP, cumulative rates of key clinical events after the onset of ICP were all different between EOICPa and LOICPa patients. Generally speaking, the development of key clinical events were more common in LOICPa patients than EOICPa patients except pancreatic stones. Similarly, 30 years old was selected as the cut-off value to classify EOICP30 and LOICP30 in an Indian study even though they didn’t mentioned why they chose 30 years old as the cut-off value, and similar differences in key clinical events between EOICP30 and LOICP30 were also found3. Thus, no matter which cut off value we use to classify EOICPa and LOICPa, we always find the differences between EOICPa and LOICPa. As a result, we assume that if the demarcation point value of the “bimodal distribution” of age at onset of ICP in Layer et al.’s study was just any other random number, EOICP and LOICP might have been defined by that random number in 1994.

Why do differences exist between EOICPa and LOICPa? The advances in radiological imaging benefits the early diagnosis of ICP which shifted the diagnosis of LOICP group to a decade earlier37. It is possible that those identified as late onset have CP which is clinically silent for decades and present with exocrine and endocrine insufficiency at later age. These patients experienced less pain due to the long term chronic inflammation according to the pancreatic burnout theory38. It is possible there is a spectrum in which patients with intense inflammation present early and low grade chronic inflammation present late so that differences exist no matter what cut-off value was used to define EOICP and LOICP. From the perspective of gene, pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (SPINK1) mutations have ever been considered to be the possible explanation of the difference between EOICP and LOICP because it was identified more frequent in EOICP than LOICP39, however, the association between the SPINK1 mutations and the age of onset of ICP is still pending. There is no definite range of age at onset of ICP in patients with SPINK1 mutations. Chang et al. just claimed SPINK1 mutation in ICP patients suggested earlier onset of age, higher frequency of constant pain, and earlier occurrence of pancreatic calcification and pseudocyst5. Sun et al. found the presence of the SPINK1 c.194 + 2 T > C mutation seemed to be associated with ICP and could predispose individuals to pancreatic diabetes at an earlier age40. However, Chandak et al. found that there was no statistical difference between age at onset of ICP patients with SPINK1 mutation and that of ICP patients without SPINK1 mutation10. Jalaly et al. concluded that ICP was not independently associated with pathogenic genetic variants41. The association of genetic factors and clinical course of ICP needs to be studied further.

This is the first study concerning the rationality of the classification of EOICP and LOICP. The study proved that the classification of EOICP and LOICP may be not unique and need to be reconsidered. But there are some limitations. First, we didn’t get the original data of Layer et al.’s study although we have tried every possible way to get the data. Thus, we were unable to present the accurate distribution with the accurate age at onset of ICP. However, we had tried our best to reduce the bias caused by data reconstruction. The mean value of lower and upper range of each age group in the bar graph (“Fig. 1” in Layer et al.’s article study1) was set as the reconstructed age of every patient in the same age group. The description of data showed few differences which indicated that the reconstruction process might not influence the result (Supplementary Table 6). Second, SPINK1 mutation wasn’t tested in our study. Thus, we failed to explore the relationship of SPINK1 mutation with ICP. Third, the retrospectively acquired data collected between January 2000 and December 2004 might introduce recall bias.

In conclusion, age at onset of ICP was proved to be right skewed distribution. Differences always exist in EOICPa and LOICPa no matter what the cut-off value is. From this perspective, EOICP and LOICP according to Layer et al.’s classification might be not unique and need to be reconsidered.

Data availability

Data will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Layer, P. Y. H., Kalthoff, L., Clain, J. E., Bakken, L. J. & DiMagno, E. P. The different courses of early- and late-onset idiopathic and alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 107, 1481–1487 (1994).

Artice search: from all databases. Cited 12 May 2019. Available from: http://www.webofknowledge.com/Search.do?product=UA&SID=C1TZyKbmGlLNFj8K5J1&search_mode=GeneralSearch&prID=a689e1a9-41e0-40cc-b85d-fb8b0ebb384d.

Rajesh, G., Veena, A. B., Menon, S. & Balakrishnan, V. Clinical profile of early-onset and late-onset idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in South India. Indian J Gastroenterol 33, 231–236, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-013-0421-3 (2014).

Bhasin, D. K. et al. Clinical profile of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in North India. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 7, 594–599, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.01.009 (2009).

Chang, Y. T. et al. Association and differential role of PRSS1 and SPINK1 mutation in early-onset and late-onset idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in Chinese subjects. Gut 58, 885, https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2007.129916 (2009).

Bhatia, E. et al. Tropical calcific pancreatitis: strong association with SPINK1 trypsin inhibitor mutations. Gastroenterology 123, 1020–1025 (2002).

Pfutzer, R. H. et al. SPINK1/PSTI polymorphisms act as disease modifiers in familial and idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 119, 615–623 (2000).

Imoto, M. D. E. Cigarette smoking increases the risk of pancreatic calcification in late-onset but not early-onset idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 21, 115–119 (2000).

Threadgold, J. et al. The N34S mutation of SPINK1 (PSTI) is associated with a familial pattern of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis but does not cause the disease. Gut 50, 675–681 (2002).

Chandak, G. R. et al. Absence of PRSS1 mutations and association of SPINK1 trypsin inhibitor mutations in hereditary and non-hereditary chronic pancreatitis. Gut 53, 723–728 (2004).

Chang, M. C. et al. Spectrum of mutations and variants/haplotypes of CFTR and genotype-phenotype correlation in idiopathic chronic pancreatitis and controls in Chinese by complete analysis. Clin Genet 71, 530–539, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00813.x (2007).

Gasiorowska, A. et al. The prevalence of cationic trypsinogen (PRSS1) and serine protease inhibitor, Kazal type 1 (SPINK1) gene mutations in Polish patients with alcoholic and idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 56, 894–901, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-010-1349-4 (2011).

Midha, S., Khajuria, R., Shastri, S., Kabra, M. & Garg, P. K. Idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in India: phenotypic characterisation and strong genetic susceptibility due to SPINK1 and CFTR gene mutations. Gut 59, 800–807, https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2009.191239 (2010).

Sun, C. et al. Serine Protease Inhibitor Kazal Type 1 (SPINK1) c.194 + 2T > C Mutation May Predict Long-term Outcome of Endoscopic Treatments in Idiopathic Chronic Pancreatitis. Medicine (Baltimore) 94, e2046, https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000002046 (2015).

Li, Z. S. et al. A long-term follow-up study on endoscopic management of children and adolescents with chronic pancreatitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol 105, 1884–1892, https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2010.85 (2010).

Li, B. R. et al. Risk Factors for Steatorrhea in Chronic Pancreatitis: A Cohort of 2,153 Patients. Scientific reports 6, 21381, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21381 (2016).

Hao, L. et al. Risk factors and nomogram for pancreatic pseudocysts in chronic pancreatitis: A cohort of 1998 patients. J. Gastroenterol Hepatol 32, 1403–1411, https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.13748 (2017).

Hao, L. et al. Risk Factors and Nomogram for Common Bile Duct Stricture in Chronic Pancreatitis: A Cohort of 2153 Patients. J. Clin. Gastroenterol 53, e91–e100, https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000000930 (2019).

Zeng, X. P. et al. Spatial Distribution of Pancreatic Stones in Chronic Pancreatitis. Pancreas 47, 864–870, https://doi.org/10.1097/mpa.0000000000001097 (2018).

Wang, D. et al. Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy for Chronic Pancreatitis Patients With Stones After Pancreatic Surgery. Pancreas 47, 609–616, https://doi.org/10.1097/mpa.0000000000001042 (2018).

Hao, L. et al. Risk factor for steatorrhea in pediatric chronic pancreatitis patients. BMC gastroenterology 18, 182, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-018-0902-z (2018).

Hao, L. et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy is safe and effective for geriatric patients with chronic pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.14569 (2018).

Li, B. R., Hu, L. H. & Li, Z. S. Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 147, 541–542, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.054 (2014).

Malde, D. J., Oliveira-Cunha, M. & Smith, A. M. Pancreatic carcinoma masquerading as groove pancreatitis: case report and review of literature. JOP: Journal of the pancreas 12, 598–602 (2011).

Dumonceau, J. M. et al. Endoscopic treatment of chronic pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Updated August 2018. Endoscopy 51, 179–193, https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0822-0832 (2019).

Li, B. R. et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy is a safe and effective treatment for pancreatic stones coexisting with pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc 84, 69–78, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2015.10.026 (2016).

Ito, T. et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for chronic pancreatitis 2015. Journal of gastroenterology 51, 85–92, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-015-1149-x (2016).

Tandon, R. K., Sato, N. & Garg, P. K. Chronic pancreatitis: Asia-Pacific consensus report. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 17, 508–518 (2002).

Hao, L. et al. Incidence of and risk factors for pancreatic cancer in chronic pancreatitis: A cohort of 1656 patients. Dig Liver Dis 49, 1249–1256, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2017.07.001 (2017).

Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes care 37 Suppl 1, S81–90, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-S081 (2014).

Affronti, J. Chronic pancreatitis and exocrine insufficiency. Primary care 38, 515–537, ix, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2011.05.007 (2011).

Regimbeau, J. M. et al. A comparative study of surgery and endoscopy for the treatment of bile duct stricture in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Surgical endoscopy 26, 2902–2908, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2283-7 (2012).

Tempero, M. A. et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, version 2.2014: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN 12, 1083–1093 (2014).

Lerch, M. M., Stier, A., Wahnschaffe, U. & Mayerle, J. Pancreatic pseudocysts: observation, endoscopic drainage, or resection? Dtsch Arztebl Int 106, 614–621, https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2009.0614 (2009).

Balthazar, E. J., Freeny, P. C. & vanSonnenberg, E. Imaging and intervention in acute pancreatitis. Radiology 193, 297–306, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.193.2.7972730 (1994).

Dominguez-Munoz, J. E. et al. Recommendations from the United European Gastroenterology evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology 18, 847–854, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2018.09.016 (2018).

Issa, Y. et al. Diagnosing Chronic Pancreatitis: Comparison and Evaluation of Different Diagnostic Tools. Pancreas 46, 1158–1164, https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0000000000000903 (2017).

Sakorafas, G. H., Tsiotou, A. G. & Peros, G. Mechanisms and natural history of pain in chronic pancreatitis: a surgical perspective. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 41, 689–699, https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0b013e3180301baf (2007).

Etemad, B. & Whitcomb, D. C. Chronic pancreatitis: diagnosis, classification, and new genetic developments. Gastroenterology 120, 682–707 (2001).

Sun, C. et al. The contribution of the SPINK1 c.194 + 2T >C mutation to the clinical course of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in Chinese patients. Dig. Liver Dis. 45, 38–42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2012.08.008 (2013).

Jalaly, N. Y. et al. An Evaluation of Factors Associated With Pathogenic PRSS1, SPINK1, CTFR, and/or CTRC Genetic Variants in Patients With Idiopathic Pancreatitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 112, 1320–1329, https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2017.106 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 81770635 (LHH), No. 81900590(DW)], Special Foundation for Wisdom Medicine of Shanghai [Grant No. 2018ZHYL0229 (LHH)], and Shanghai Sailing Program [Grant No. 19YF1446800 (DW)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yu Liu, Dan Wang, and Yi-Li Cai participated in the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, as well as in the manuscript drafting; Tao Zhang, Hua-Liang Chen, Lu Hao, Teng Wang, Di Zhang, Huai-Yu Yang, Jia-Yi Ma, Juan Li, Ling-Ling Zhang, Cui Chen, Hong-Lei Guo, Ya-Wei Bi, Lei Xin, Xiang-Peng Zeng, Hui Chen, Ting Xie, Zhuan Liao, Zhi-Jie Cong and Zhao-Shen Li participated in data acquisition and manuscript drafting; Liang-Hao Hu contributed to the conception, design, and data interpretation, as well as revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Drs. Liu, Wang and Cai contributed equally to this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplemenatry information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Wang, D., Cai, YL. et al. Classification of Early-Onset and Late-Onset Idiopathic Chronic Pancreatitis Needs Reconsideration. Sci Rep 10, 10448 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67306-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67306-w