Abstract

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are standard adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with oestrogen receptor-positive, early-stage, and metastatic breast cancer. Although effective, the risk of falls due to AI-associated knee joint pain significantly increased. The aim of this study was to evaluate the therapeutic effects of yoga and massage on AI-associated knee joint pain. Breast cancer survivors were randomly assigned to a 6-week yoga intervention-2-week rest-6-week massage exposure (Yoga first, n = 30) or a 6-week massage intervention-2-week rest-6-week yoga exposure (Massage first, n = 30). Evaluations of the treatment efficacy were made at baseline, post-intervention, and post-exposure using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scale, plasma cytokine levels, and changes in meridian energy. The results showed that yoga, superior to massage intervention, significantly reduced AI-associated knee joint pain, as demonstrated by the WOMAC pain score. The yoga intervention improvements were also associated with changes in plasma cytokine levels and meridian energy changes. In conclusion, this study provides scientific evidence that yoga was more effective than massage for reducing AI-associated knee joint pain. Meridian energy changes may provide another scientific, objective, non-invasive way to monitor the therapeutic effects of yoga and investigate another alternative, complementary medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are typical standard adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with oestrogen receptor-positive, early-stage, and metastatic breast cancer1,2,3. AIs significantly improve disease-free survival and recurrence of the malignancy4,5,6. Tamoxifen has been used as the primary endocrine therapy for over three decades. Third-generation AIs (anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane) have a higher potency7. Although effective, AIs often increase the risk of various side effects such as mental or memory problems, osteoporosis or bone fractures, AI-associated arthralgia (AIA), and other unclear effects on heart health. AIA is the most common side effect, and it affects 33–74% of patients treated with AIs8,9,10,11,12. Although the location is generalized in most cases13, a recent study has demonstrated the relationship between arthralgia and falls among AI users, which may attribute to the arthralgia of the knee. According to the survey, 35% of breast cancer survivors reported falls 12–24 months after using an AI. Among women who fell, 2–8% reported seeking medical assistance14. The majority of the first pain events developed within 24 months of initiation of treatment (anastrozole 68%, tamoxifen 59%) with a peak occurrence at 6 months (anastrozole 29%, tamoxifen 20%)13. Although the events were mild-to-moderate in intensity and did not lead to withdrawal of AI treatment13, studies suggest that AIs affect the quality of life with 20–32% of women stopping AI treatment primarily due to AIA15,16,17. As compliance is critical for the success of AI therapy, an intervention to alleviate AIA especially AI-associated knee joint pain, is needed18. Pharmacological remedies provide little or no joint symptom relief19. Therefore, an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for AIA management is urgently needed.

Potential alternative and complementary interventions such as acupuncture, herbs, vitamins, and physical therapies, such as aerobic/resistance exercise, walking, and yoga show promise for relieving AIA symptoms19. A previous meta-analysis revealed positive results with the omega-3 fatty acid20. The heterogeneity of physical therapies and the required cohort sizes make it difficult to identify significant benefits20. A randomized controlled trial has found that yoga significantly reduced joint pain post-intervention and 90 days later compared to the pre-intervention condition. However, the scale used for joint pain evaluation might not have reflected the joint function21. Another single-arm study revealed that yoga significantly improved the worst AI-associated joint pain. However, the sample size was small and again the scale used for pain evaluation might not have reflected the joint function22. More scientific evidence for evaluating the effects of yoga intervention is required. Therefore, this randomized, controlled study aims to evaluate the efficacy of yoga compared to massage for relief of AI-associated knee joint pain. The feasibility of the interventions was assessed, and meridian energy was measured as a non-invasive method to monitor the therapeutic effects of yoga. To our knowledge, this is the first assessment of meridian energy to measure the efficacy of yoga.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

The baseline characteristics of the participants, including age, height, body weight, breast cancer stage, pain time, and exercise habits, are presented in Table 1. Participants' age ranged from 41–70 years, with an average of 53.9 ± 6.4 years. Although a significant difference was found in body weight (p = 0.026), body mass index was not affected. There were no other significant differences in the baseline characteristics of the two groups.

Attendance and adherence

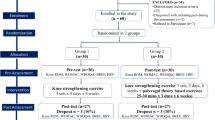

Randomization assignment and participant flow by the group were shown in Fig. 1. Written informed consent was obtained from 73 participants, and 60 participants were eligible. Of those who enrolled, two who did not complete baseline assessments and six who did not complete the post-exposure evaluation (13.3%) were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 1). The main reasons for discontinuation were inconvenience (one participant stated family care requirements, two said work requirements, one indicated traffic inconvenience, two had travel scheduled), and personal reasons (one participant had a common cold, one gave no reason). The remaining 52 participants completed all interventions.

Intervention effects on WOMAC pain scores

Results for the mean WOMAC pain score for the AI-associated knee joint pain are summarized in Table 2. Analysis of covariance analyses (ANCOVA) were not needed to adjusted for baselines due to the homogeneity of regression slopes assumption does not hold (there were covariate by treatment interaction-effect: F(1, 54) = 12.889, p = 0.001 for week 7, and F(1, 48) = 9.477, p = 0.003 for week 14). The average WOMAC pain score for the AI-associated knee joint pain decreased from 9.3 ± 2.8 at baseline to 4.2 ± 2.2 after yoga intervention in the Yoga first group (p = 1.211 × 10−10) during the intervention period. The improvements of yoga intervention were sustained for at least one week. However, there was no significant change in the pain scores after massage intervention in the Massage first group (9.7 ± 3.2 to 8.7 ± 4.2, p = 0.320). The WOMAC pain scores also decreased to 3.6 ± 2.1 after the 1-week rest and 6-week yoga exposure in the Massage first group, proving no group arrangement bias. However, the WOMAC scores reverted to 8.8 ± 3.1 after the 1-week rest and 6-week massage exposure in the Yoga first group suggested the benefits from yoga intervention could not sustain eight weeks. The results showed that yoga intervention is significantly superior to massage intervention to improve AI-associated knee joint pain. Meanwhile, the benefits of yoga intervention for the AI-associated knee joint pain were sustained for at least one week, but not eight weeks, implying that continual yoga intervention would be critical for the pain management.

Intervention effects on inflammation

Results for estimated mean plasma cytokines after adjusting for baseline levels are summarized in Fig. 2 and Table 3; unadjusted group means for all outcome variables at each of the three measurement times are available in the supplementary Table 1. The level of IFNγ of all samples was under the detection limit was excluded from statistical analyses. There were no significant differences upon the interventions for TNF-α and IL1-β at baseline, one-week post-treatment, or post-exposure. After adjusting for baseline levels, mean TNF-α levels were not significantly different between groups (week 7 visit: 36.1 ± 1.2 vs. 37.7 ± 1.2, p = 0.360; week 14 visit: 34.7 ± 0.9 vs 37.0 ± 0.9, p = 0.082). Although IL1-β levels showed a substantial difference over time between the two groups, the difference appeared due to individual variations. The average IL1-β level was significantly lower in yoga first group compared with massage first group at only week 7 visit (7.8 ± 0.2 vs. 8.6 ± 0.2, p = 0.002) but not week 14 visit (7.8 ± 0.2 vs. 8.3 ± 0.2, p = 0.113). Those alternations did not mirror the pain score, and could not attribute to a specific intervention. These results indicated that the pain improvement was not significantly associated with levels of inflammatory cytokines such as plasma TNF-α, IFNγ and IL1-β.

Changes in plasma cytokine levels including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (A) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (B) at baseline, one-week post-intervention (week 7), and post-exposure (week 14) in the Yoga and Massage groups. Results shown are mean ± SE from analysis of covariance tests adjusting for baseline levels. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Intervention effects on meridian energy (ME)

Results for estimated mean meridian energy after adjusting for baseline levels are summarized in Fig. 3 and Table 3; unadjusted group means for all outcome variables at each of the three measurement times are available in the supplementary Table 2. ANCOVA supported a significant difference favouring yoga over massage for the Week 7 ME enhancement via modulating spleen (SP3, adjusted mean ± SE 47.1 ± 3.3 vs. 35.1 ± 3.3, Yoga first group vs. Massage first group, p = 0.015), kidney (KI3, adjusted mean ± SE 41.8 ± 3.1 vs. 27.3 ± 3.1, Yoga first group vs. Massage first group, p = 0.001), gallbladder (GB40, adjusted mean ± SE 35.9 ± 2.9 vs. 26.4 ± 2.9, Yoga first group vs. Massage first group, p = 0.021) and bladder (BL65, adjusted mean ± SE 41.0 ± 2.7 vs. 27.6 ± 2.7, Yoga first group vs. Massage first group, p = 0.001) after adjusted by the baseline. However, the ME of SP3, KI3, GB40, BL65, and additional stomach (ST42) were back after the 1-week rest and 6-week massage exposure in the Yoga first group, mirrored the limited time period of yoga intervention. Not only ME of SP3, KI3, GB40, and BL65, but large intestine (LI5), triple energizer (TE4), Liver (LI5), and ST42 were enhanced. However, the significantly favoring Massage first group over Yoga first group for the Week 14 ME of LI5, TE4, SI4, SP3, LR3, KI3, ST42, GB40, and BL65 after adjusted by the baseline, may also attribute to the carry-out effect (Levene test, p < 0.05). No intervention-related safety issues were encountered. These results provide evidence that monitoring meridian energy changes may be a reliable, scientific, and objective non-invasive way to monitor the therapeutic effect of yoga or other alternative and complementary therapies.

Changes in meridian energy of (A) lung meridian (Taiyuan, LU9), (B) pericardium meridian (Daling, PC7), (C) heart meridian (Shenmen, HT7), (D) large intestine meridian (Hegu, LI5), (E) triple energizer meridian (Yangchi, TE4), (F) small intestine meridian (Wangu, SI4), (G) spleen meridian (Taibai, SP3), (H) liver meridian (Taichong, LR3), (I) kidney meridian (Taixi, KI3), (J) stomach meridian (Chongyang, ST42), (K) gallbladder meridian (Qiuxu, GB40), (L) bladder meridian (Jinggu, BL65) at baseline, one-week post-intervention (week 7), and post-exposure (week 14) in the Yoga and Massage groups. Results shown are mean ± SE from analysis of covariance tests adjusting for baseline levels. *p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Adverse events

There were no cases of recurrent or metastatic breast cancer detected during the trial. In addition, no intervention-related safety issues were encountered. Events that were potentially attributable to the yoga intervention included five patients with mild dizziness, thirteen with muscle aches, and eight with tiredness. One participant stated all three events.

Discussion

The current results show that yoga intervention is significantly superior to massage intervention to improve AI-associated knee joint pain, as evaluated by the WOMAC index score. No safety issues were noted with either intervention. While the improvement with yoga intervention can be sustained for at least one week, it cannot be sustained for eight weeks, highlighting the importance of continual yoga intervention. Changes in plasma cytokines and meridian energy provide an additional scientific, objective, non-invasive way to support the therapeutic effects.

In the current study, patient compliance with treatment was good, with 96.7% of participants completing the baseline and post-intervention assessments and 86.7% of participants completing the trial. Although we believe the flexible class arrangements increased the participation rate compared to other randomized controlled trials, a few participants still dropped out due to inconveniences, including class time and location. Decentralized community yoga classes or home-based online yoga classes provided by instructors after an initial in-person class may help improve participant compliance. A greater understanding of the attitudes and barriers to yoga practice will help provide better yoga programs aligned to the population's needs. The social support status, fatigue, and depressive symptoms were not part of the inclusion criteria. However, beneficial observations were seen for fatigue, vitality, and insomnia, all commonly reported by patients taking AIs. These factors may warrant further investigation.

Although a previous study showed that yoga practice substantially reduced inflammatory cytokines23, only a similar trend of IL1-β, but not TNF-α was not found in our trial. In the previous study, lipopolysaccharide-stimulated production of interleukin-6 (IL-6), TNF-α, and IL-1β from isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells was measured by using an electrochemiluminescence method23, which may reflect anti-microbial infection abilities. However, in current study, the levels of plasma TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL1-β were measured by using ELISA, reflecting the physiological conditions. Besides, the detection time point, population differences, and personal differences may account for these results. Exercise training reduces inflammation are sparse and inconsistent24,25. Weight loss may be crucial for the change in inflammatory cytokines24,25. Further study is warranted to assess the impact of yoga on cytokines.

Measurement of meridian energy changes was used as a novel method to evaluate the efficacy of study interventions. Meridian energy theory is based on traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and remains debated in Western medicine26. The meridian system is a series of pathways that conduct energy, known as "qi", throughout the body. The meridians are associated with two balanced forces, "yin" and "yang". Disruption to the flow of energy in these pathways is believed to be the cause of illness. The meridian energy analysis device (MEAD), with reproducibility of 93.2%, has been recognized as a reliable complementary device for evaluating the efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) therapy, related sympathetic conditions, and tracing the meridian flow27,28. A review with recommendations for clinical trials has been suggested29. We designed the studies based on this advice and performed measurements that followed the manufacturer's instructions to maximize the reliability.

It was noted that there were participants with a relative meridian energy deficiency (less than 50 μA) at the spleen (SP3), liver (LR3), kidney (KI3), stomach (ST42), gallbladder (GB40), and bladder (BL65), suggesting that AI-associated knee joint pain in breast cancer survivors has a deficiency syndrome through these meridians. According to the current results, the yoga intervention superior over massage intervention via improving spleen (SP3), kidney (KI3), gallbladder (GB40) and bladder (BL65) energy. According to TCM theory, the yang meridians of the stomach (ST42), gallbladder (GB40) and bladder (BL65) distribute energy from the head, across the trunk, along the front, lateral, and back sides of the leg to the foot, repectively. The yin meridians of the spleen (SP3), liver (LR3), and kidney (KI3) distribute energy from the foot, up the inner side of the leg, across the front of the abdomen, and chest to the head. The meridians that demonstrated improvement with yoga intervention contribute mainly to the leg, which coincides with the improved knee pain and WOMAC score results. The bladder meridian (BL65) is the longest meridian and the largest detoxification and dehumidification channel of the human body. Improvement of BL65 energy will help to eliminate the phlegm and waste in the body. When BL65 energy is lower, moisture and toxins could not be excreted from the body, which will easily lead to blood stasis and cause many physical pains. Moreover, the KI3 and the BL65 are mirrored. Improvement of the BL65 is believed to increase the metabolism and excretion of moisture and toxins in the body through urine, by which reduce body pain. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to link meridian energy to the evaluation of yoga intervention. The energy increased by yoga intervention is thought to be "qi", which has been implied as mitochondria30. However, minimal resources have been invested in understanding mitochondrial biology and genes due to the lack of feasible methods and facilities. A better understanding of mitochondria may bridge the gap between Western medicine and TCM.

The limitation of the current study includes the existence of the carry-out effect. Although each subject has received two different treatments, yoga and massage, after random entry into the trial, with yoga first group receives yoga and then massage treatment, and the massage first group massage first and then yoga treatment. A more appropriate washout period or more frequent measurements may help to identify the real treatment effect.

In conclusion, the current results show that yoga intervention reduces AI-associated knee joint pain in breast cancer survivors, as demonstrated by the reduced WOMAC score. In addition, it supports the feasibility and potential efficacy of yoga intervention and provides scientific evidence that yoga is more effective than massage for reducing AI-associated knee joint pain. Measurement of the meridian energy change using a reliable device might be a potential, scientific, objective, and non-invasive way to monitor the therapeutic effects of yoga as well as any other alternative, complementary medicine. Future studies with larger cohorts are warranted.

Methods

Study design

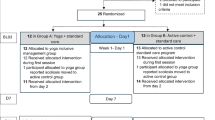

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) compared a yoga intervention with a home-based massage intervention. Breast cancer survivors were randomly assigned to a 6-week yoga intervention-2-week rest-6-week massage exposure (Yoga first, n = 30) or a 6-week massage intervention-2-week rest-6-week yoga exposure (Massage first, n = 30). Questionnaires and blood samples were collected at baseline, one-week post-intervention, and one-week post-exposure. The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of China Medical University Hospital (CMUH107-REC3-102, approved on 06/09/2018) and retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03956875, recorded on 21/05/2019). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Sixty patients with stage I–III breast cancer stage (mean age 53.9 ± 6.4 y; range 41–70 years at enrolment) from the China Medical University Hospital were enrolled from 06/09/2018 to 05/09/2019. Participants were recruited through oncologist referrals, community print advertisements and announcements, and breast cancer groups and events. Patients were required to have diagnosed stage I–III breast cancer at the time of examination, be currently taking AIs, and have a history of AI-associated knee joint pain for at least 3 months. Patients were excluded if suffering from multiple non-breast cancer-related pain sources, such as visceral pain and trauma pain. Other exclusions included: patients with addictive drug abusers; patients who might become pregnant or had delivered a baby within 3 months; patients unable to understand or give informed consent due to severe mental illness, an unstable mental state, severe hearing or visual impairment, or dementia; patients unable to practice yoga due to severe limb oedema, skin damage, and spinal disease; patients who had participated in yoga in the past month, or with routine exercise for more than 90 min per week; and patients with stage IV metastatic breast cancer.

Sample size estimation

The sample size was estimated based on detecting meaningful differences in primary endpoints with 80% power and a one-sided 5% significance level using G*Power 3.131,32. Effect sizes were based on a previously published study23 and data we collected from earlier experience. The estimated requirement was 26 patients per group, with 10% attrition expected, resulting in 30 patients per group. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist is provided in Fig. 1 (http://www.consort-statement.org/consort-2010)33.

Randomization

Sixty participants who met the inclusion criteria and provided written informed consent were randomly divided into the Yoga first and Massage first groups, with 30 in each group. Random numbers were produced through randomization using Excel version 16.0 (Microsoft Office, Redmond, WA, USA). Dr. Chia-Lin Tsai performed simple randomization. The random numbers were placed into sealed envelopes. A serial number was assigned to each envelope by the yoga instructors following the allocation sequence of the randomized numbers. Each envelope was opened sequentially according to the admission sequence of participants at the research centre. The number inside the envelope determined the group the participant was allocated. The study included an intervention period, a washout, and an exposure period. The Yoga first group performed yoga exercises two times per week for six weeks (intervention), rested for two weeks, and then completed six weeks of home-based massage (exposure). The Massage first group performed six weeks of home-based massage (intervention), rested for two weeks, then performed yoga twice a week for six weeks (exposure).

Interventions

Yoga classes were led by two certified yoga instructors and were held every morning in a private classroom specifically for study participants, providing participants flexibility in scheduling the twice weekly, sixty-minutes class time. The class format included Mindfulness yoga, the traditional Hatha yoga modified for different conditions and symptoms34. Sequences included standing poses, forward extensions, inversions, backbends, and twists. Participants were assisted in adopting a series of postures and using breathing techniques designed by the instructors. Assistance included ad hoc props such as blocks, pillows, or blankets when required.

Assessment of pain

The pain section of the Chinese version of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scale35,36 was used to evaluate intervention outcomes. The pain scale contained 5 items that were scored on a scale of 0–4 (0 = none, 1 = slight, 2 = moderate, 3 = very, 4 = extremely). All assessments were evaluated by the same well-trained physician who was blinded to the study randomization to ensure reliability and validity.

Measurement of meridian energy

The energy of the twelve regular meridians37 was measured with a meridian energy analysis device (MEAD ME-20, Medpex. Inc., Taichung, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A relative current less than 50 (A was considered "deficiency" syndrome and greater than 90 (A was considered "excess" syndrome. All measurements were recorded twice on each side by the same well-trained physician who was blinded to study randomization to ensure reliability and validity.

Plasma cytokine measurement

All separated plasma samples were stored at − 80 °C until analysis. All measurements were performed using the TNF alpha Human Uncoated ELISA Kit (Cat # 88–7346-88), IFN gamma Human Uncoated ELISA Kit (Cat # 88–7316-88), and IL-1 beta Human Uncoated ELISA Kit (Cat # 88–7261-88) obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the PASW Statistics 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-square, paired t tests, idependent sample t test, analysis of variance, or ANCOVA were used to evaluate the associations between groups when appropriate.

References

Baum, M. et al. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet 359, 2131–2139. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09088-8 (2002).

Goss, P. E. et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 1793–1802. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa032312 (2003).

Howell, A. et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet 365, 60–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6 (2005).

Regan, M. M. et al. Assessment of letrozole and tamoxifen alone and in sequence for postmenopausal women with steroid hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: the BIG 1–98 randomised clinical trial at 8.1 years median follow-up. The Lancet. Oncol. 12, 1101–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70270-4 (2011).

Cuzick, J. et al. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol. 11, 1135–1141. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70257-6 (2010).

Regan, M. M. et al. Interpreting Breast International Group (BIG) 1–98: a randomized, double-blind, phase III trial comparing letrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant endocrine therapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res https://doi.org/10.1186/Bcr2837 (2011).

Coleman, R. E. et al. Aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia: clinical experience and treatment recommendations. Cancer Treat. Rev. 34, 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.10.004 (2008).

Nahm, N., Mee, S. & Marx, G. Efficacy of management strategies for aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 14, 374–382. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.12845 (2018).

Sahin, S., Karatas, F., Sever, A. R., Altundag, K. Current management of aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia. J. B.U. Oncol 21, 17–20 (2016).

Younus, J. & Kligman, L. Management of aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia. Curr. Oncol. 17, 87–90. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.v17i1.474 (2010).

Beckwee, D., Leysen, L., Meuwis, K. & Adriaenssens, N. Prevalence of aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support. Care Cancer 25, 1673–1686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3613-z (2017).

Crew, K. D. et al. Prevalence of joint symptoms in postmenopausal women taking aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 3877–3883. https://doi.org/10.1200/Jco.2007.10.7573 (2007).

Buzdar, A. U. Clinical features of joint symptoms observed in the ‘Arimidex’, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 551–551. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2006.24.18_suppl.551 (2006).

Basal, C. et al. Joint pain and falls among women with breast cancer on aromatase inhibitors. Supp. Care Cancer 27, 2195–2202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4495-4 (2019).

Fields, J., Richardson, A., Hopkinson, J. & Fenlon, D. Nordic walking as an exercise intervention to reduce pain in women with aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia: a feasibility study. J. Pain Symptom. Manage 52, 548–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.03.010 (2016).

Shen, S. et al. Omega-3 fatty acid use for obese breast cancer patients with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia (SWOG S0927). Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 172, 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4946-0 (2018).

Henry, N. L. et al. Predictors of aromatase inhibitor discontinuation as a result of treatment-emergent symptoms in early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 936–942. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0261 (2012).

Crew, K. D. et al. Prevalence of joint symptoms in postmenopausal women taking aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 3877–3883. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7573 (2007).

Roberts, K., Rickett, K., Greer, R. & Woodward, N. Management of aromatase inhibitor induced musculoskeletal symptoms in postmenopausal early Breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hemat. 111, 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.01.010 (2017).

Lustberg, M. B. et al. Prevention of aromatase Inhibitor (AI)-induced joint symptoms with omega-3 fatty acid supplementation: A randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. Cancer Res. https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS14-P1-09-03 (2015).

Carson, J. W., Carson, K. M., Porter, L. S., Keefe, F. J. & Seewaldt, V. L. Yoga of Awareness program for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results from a randomized trial. Supp. Care Cancer 17, 1301–1309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0587-5 (2009).

Galantino, M. L. et al. Impact of yoga on functional outcomes in breast cancer survivors with aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgias. Integr. Cancer Ther. 11, 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735411413270 (2012).

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. et al. Yoga’s impact on inflammation, mood, and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/Jco.2013.51.8860 (2014).

Calder, P. C. et al. Dietary factors and low-grade inflammation in relation to overweight and obesity. Br. J. Nutr. 106(Suppl 3), S5-78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114511005460 (2011).

Beavers, K. M., Brinkley, T. E. & Nicklas, B. J. Effect of exercise training on chronic inflammation. Clin. Chim. Acta 411, 785–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2010.02.069 (2010).

Ahn, A. C. et al. Electrical properties of acupuncture points and meridians: a systematic review. Bioelectromagnetics 29, 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/bem.20403 (2008).

Nakatani, Y. Skin electric resistance and ryodoraku. J. Auton Nerv. Syst. 6, 52 (1956).

Tsai, M. Y., Chen, S. Y. & Lin, C. C. Theoretical basis, application, reliability, and sample size estimates of a Meridian Energy Analysis Device for Traditional Chinese Medicine Research. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 72, 254–257. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2017(04)10 (2017).

Colbert, A. P., Spaulding, K., Larsen, A., Ahn, A. C. & Cutro, J. A. Electrodermal activity at acupoints: literature review and recommendations for reporting clinical trials. J. Acupunct. Meridian Stud. 4, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2005-2901(11)60002-2 (2011).

Wallace, D. C. Mitochondria as chi. Genetics 179, 727–735. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.104.91769 (2008).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146 (2007).

tests for correlation and regression analyses. Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., Lang, A. G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 31: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149(2009) (2009).

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D. & Group, C. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials 11, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-11-32 (2010).

Bower, J. E. et al. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 118, 3766–3775. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26702 (2012).

Bellamy, N., Buchanan, W. W., Goldsmith, C. H., Campbell, J. & Stitt, L. W. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J. Rheumatol. 15, 1833–1840 (1988).

Xie, F. et al. Validation of Chinese Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) in patients scheduled for total knee replacement. Qual. Life Res. 17, 595–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9340-7 (2008).

Deadman, P. A.-K., M. Baker, K. A Manuel of Acupuncture. 2nd edn, (EASTLAND PRESS, 2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients for participating in this study, the Taichung Sen Breath Yoga Classroom, to provide professional venues and yoga instructors, and research nurses for their assistance in conducting the research. This work is supported by the Drug Development Centre, China Medical University and the Chinese Medicine Research Centre, China Medical University under the Featured Areas Research Centre Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan, the Ministry of Education in Taiwan (10971701), and Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 107-2320-B-039-032-MY3). The sponsor/funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: C.-L.T., Y.-H.L., C.-L.H. Financial support: Y.-H.L., C.-L.H. Provision of study materials or patients: C.-L.T., L.-C.L., C.-Y.L., Y.-H.L., C.-L.H. Collection and assembly of data: C.-L.T. Data analysis and interpretation: C.-L.T., Y.-H.L., C.-L.H. Statistics: W.-L.L., C.-L. T., Y.-H.L. Manuscript writing: Y.-H.L., C.-L.H. Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, CL., Liu, LC., Liao, CY. et al. Yoga versus massage in the treatment of aromatase inhibitor-associated knee joint pain in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 11, 14843 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94466-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94466-0

This article is cited by

-

Integrative Approaches for Cancer Pain Management

Current Oncology Reports (2024)