Abstract

The body mass index (BMI) neither differentiates fat from lean mass nor does it consider adipose tissue distribution. In contrast, the recently introduced z-score of the log-transformed A Body Shape Index (LBSIZ) can be applied to measure obesity using waist circumference (WC), height, and weight. We aimed to investigate the association between LBSIZ and mortality. We used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2014 and linked the primary dataset to death certificate data from the National Death Index with mortality follow-up through December 31, 2015. A multiple Cox regression analysis was performed to evaluate the hazard ratio (HR) of all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortalities with adjustment for baseline characteristics. LBSIZ, WC, and BMI showed positive association with total fat percentage (P < 0.001); however, only WC and BMI were positively associated with appendicular skeletal mass index (ASMI) (P < 0.001). In the multiple Cox regression analysis, only LBSIZ showed a significant HR for all-cause and CVD mortalities. Under restricted cubic spline regression, mortality risk increased with LBSIZ. However, BMI and WC showed a U-shape association. In conclusion, LBSIZ is strongly associated with all-cause and CVD mortalities. Since LBSIZ is independent of BMI, LBSIZ complements BMI to identify high-risk groups for mortality even in individuals with low or normal BMI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, 13% of the world’s population in 2016 were obese, and the prevalence of obesity has increased dramatically by approximately threefold in the last 30 years1. Obesity is a risk factor for several diseases, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, cerebral infarction, and cancer, and is associated with approximately 4.8% of mortality worldwide2,3,4,5,6. Such increasing prevalence and clinical significance suggest the importance of accurate diagnosis of obesity.

Non-invasive tests performed for the accurate measurement of body fat include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), and positron emission tomography/CT; however, these tests are associated with a high-cost burden and low accessibility. Therefore, body mass index (BMI), which is calculated using a simple formula of weight divided by square of the height (kg/m2), has been used to define obesity. However, BMI does not differentiate between muscle and fat, and thus is inaccurate in estimating body fat content7. As a result, it is not unexpected that BMI is limited in predicting the risk of CVD, diabetes, cerebral infarction, cancer, and death8,9,10.

A Body Shape Index (ABSI), which is a power law expressing waist circumference (WC)/expected value for WC, considering weight and height (i.e. BMI), was derived from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). ABSI adjusts WC for BMI so that ABSI and BMI will become statistically independent11. In a 2018 meta-analysis study, ABSI was associated with high blood pressure, diabetes, CVD, and its association with mortality was stronger than that of BMI or WC12. As initially described, ABSI is sex dependent (higher in males than females) and increases with age. It was suggested that z scores be computed with adjustments for gender and age. An important finding has shown that, unlike BMI, ABSI has been applicable across a range of populations and demographics. As with BMI, scaling exponent adjustments customized to other populations demonstrated only small differences13. However, the skewness and lack of cut-off values has been said to limit the identification of the high-risk groups for obesity-related diseases, and the scaling exponents may differ by ethnicity14,15. The use of ABSI in clinical settings has been suggested16,17, but remains largely preclinical and has not been documented in the literature. Alternatively, the use of Z scores, log-transformed A Body Shape Index (LBSIZ) has been suggested to complement ABSI with respect to the noted limitations14,18. LBSIZ can predict hypertension and health-related quality of life15 and is associated with the risk of CVDs in the Korean population. Furthermore, in a cross-sectional study using the NHANES, LBSIZ was significantly correlated with the risk of CVDs19. However, there are no longitudinal studies on LBSIZ outside Korea.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the association between LBSIZ and risk of all-cause and CVD mortalities using the NHANES, a representative sample of the United States population, from which ABSI was initially derived.

Results

Baseline characteristics

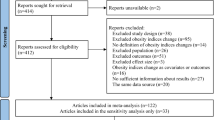

In total, 24,987 adults aged 20–85 years were included in this study (Fig. 1). The mean age of the participants was 52.9 ± 17.4 years, and 51.7% of them were women. The mean BMI and WC values, respectively, were 28.9 ± 5.7 kg/m2 (range 15.4–74.1) and 102.9 ± 14.9 cm (range 61.8–178.2) in men, and 29.7 ± 5.2 kg/m2 (range 13.4–82.1) and 98.1 ± 15.9 cm (range 58.8–172.5) in women. In total, 3,355 participants died during a mean follow-up period of 90.6 ± 53.5 months (median: 83 months). Of those, 755 deaths were due to CVD. Table 1 shows the demographic, anthropometric, and clinical characteristics according to the all-cause mortality of the participants. The mean age, proportion of males, smokers, and drinkers were higher in those who died than in survivors. In addition, systolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and triglyceride levels were higher, whereas high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol level was lower in participants who died. The prevalence rates of previous CVD, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia were also higher in this group. Appendicular skeletal mass index (ASMI) was significantly lower in participants who died due to CVD; however, there was no significant difference in total fat percentage. The mean BMI of participants who died was 28.4 ± 6.1 kg/m2 (range 13.4–64.7), and it was significantly lower in the survivors (p < 0.001) at 29.5 ± 6.6 kg/m2 (range 14.2–82.1). However, the obesity parameters WC and LBSIZ were higher in those who died than in survivors.

Association between obesity parameters and body composition

BMI and WC were positively correlated with ASMI and total fat percentage. In contrast, LBSIZ was positively correlated with total fat percentage and negatively correlated with ASMI. Similar findings were observed following subgroup analysis by sex (Table 2).

Association between obesity parameters and mortality

In the multiple Cox regression analysis, an increase in LBSIZ was significantly associated with high all-cause mortality rate (hazard ratio [HR] 1.218, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.169–1.270, P < 0.001), whereas BMI and WC had a negative association with all-cause mortality (BMI, HR: 0.982, 95% CI 0.976–0.989, P < 0.001; WC: 0.997, 95% CI 0.994–0.999, P = 0.018; Table 3). An increase in LBSIZ led to a significant increase in the risk of CVD death; however, BMI and WC were not associated with CVD mortality. In the subgroup analyses according to sex, an increase in LBSIZ was significantly associated with high all-cause and CVD mortalities regardless of sex (Table 3). In the analysis with propensity score matching (PSM) data20, an increase in LBSIZ led to a significant increase in the risk of all-cause and CVD death, whereas BMI had a negative association with all-cause and CVD mortalities (Table 3).

In the subgroup analyses according to previous CVD status and history of cancer at the baseline survey, an increase in LBSIZ was significantly associated with high all-cause mortality, whereas BMI had a negative association regardless of underlying diseases (Table 4). An increase in LBSIZ led to a significant increase in the risk of CVD death; however, BMI and WC were not associated with CVD mortality in all subgroups with respect to previous CVD status and history of cancer (Table 4).

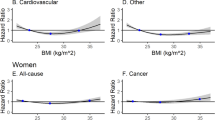

On the restricted cubic spline regression plot, the HR for all-cause death and CVD death increased as LBSIZ increased. This continuous increase occurred more sharply past the midpoint. However, BMI and WC showed a U-shaped association with the HR for all-cause and CVD mortalities (Fig. 2). Further analysis according to BMI classification showed that an increase in LBSIZ was positively associated with all-cause mortality in all subgroups, whereas WC was associated with all-cause mortality only for BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (Table 5).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the association between all-cause and CVD mortalities, LBSIZ, BMI, and WC using a representative sample of the United States population. WC and BMI were positively correlated with body fat percentage and ASMI. LBSIZ was positively correlated with body fat percentage and negatively correlated with ASMI. In addition, multiple Cox regression analysis revealed that LBSIZ had significant HRs for all-cause mortality (HR: 1.22, 95% CI 1.17–1.27) and CVD mortality (HR: 1.24, 95% CI 1.14–1.36). The HR for all-cause death and CVD-related death increased as LBSIZ increased, whereas BMI and WC showed a U-shaped association.

Previous studies have reported an obesity paradox, suggesting that obesity may be associated with a decrease in mortality rate21,22,23. In a systemic review of 40 cohort studies, patients with low BMI (< 20 kg/m2) had a greater relative risk for total and CVD mortalities and overweight patients (BMI: 25–29.9 kg/m2) had a lower risk for total and cardiovascular mortalities, compared with those with normal BMI24. In another study, overweight (BMI 25–30 kg/m2) and obese (BMI 30–35 kg/m2) patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease had lower all-cause mortality, compared with normal weight patients (BMI 20–25 kg/m2)21. This can be explained by the fact that obesity was defined using BMI1, which cannot accurately distinguish fat, mineral, muscle mass, and is limited in measuring body fat1,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Aging is associated with decreased muscle mass and increased body fat. However, BMI fails to reflect these changes and cannot assess differences in distribution of body fat by sex26,27. Various studies have reported an association between muscle mass and mortality33,34,35. In one cohort study conducted in Mexico, patients diagnosed with sarcopenia had a 1.39-fold higher risk of mortality33. In a cross-sectional study using the US NHANES data, older women with sarcopenia had an increased rate of all-cause mortality34. Considering the association between BMI and muscle mass19, many patients with low BMI are more likely to have sarcopenia, which could explain the obesity paradox36,37. Additionally, recent studies have reported that sarcopenic obesity is associated with an increase in mortality38. Elderly women with sarcopenic obesity had an increased all-cause mortality in a cross-sectional study using the US NHANES33. Moreover, in a meta-analysis examining prospective cohort studies, sarcopenic obesity increased the risk of all-cause mortality by 24%39. BMI is positively correlated with muscle mass and fat mass19. Thus, BMI cannot differentiate between patients with sarcopenic obesity, low muscle mass, high fat mass, and normal healthy individuals with sufficient muscle mass and low fat mass40. Herein, BMI was positively correlated with muscle and fat masses, and BMI and mortality risk had a U-shaped association, suggesting a paradox of obesity. As BMI has limitations, many studies have attempted to investigate obesity using other body indices, such as WC41. WC is closely associated with visceral fat and increased metabolic risk, morbidity, and mortality42,43. However, WC cannot discriminate between subcutaneous and visceral fat accumulation, and there is a lack of data related to age and sex to define obesity using WC26,44. In our study, similar to BMI, WC was positively correlated with muscle mass and fat mass. WC and mortality risk had a U-shaped association, suggesting a paradox of obesity.

As BMI and WC are limited, various groups of researchers have explored different indicators of obesity41,45. In 2012, Krakauer et al. suggested ABSI for the first time using WC, weight, and height data from 1999 to 2004 US NHANES11. ASBI is a more effective predictor of premature death than BMI and WC, and is an effective prognostic factor for all-cause mortality11,46. In a systematic review of 38 studies, including 24 retrospective cohort studies and 14 cross-sectional studies in 15 different countries, increased ABSI led to 13%, 35%, 21%, and 55% increases in the risks of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, CVD, and all-cause mortality, respectively12. In NHANES 1999–2004, ABSI was a strong risk factor for mortality, and similar findings were observed for mortality risk in UK samples11,47. Moreover, ABSI was superior to other anthropometric obesity indices, such as waist-to-height-ratio and waist-to-hip ratio47. Several studies have reported positive associations of ABSI with trunk fat mass48 and visceral adipose mass49, and inverse associations with fat free mass15,19,50,51 and hand grip strength52. Furthermore, A large cohort study in UK reported that body-shape phenotypes combining ABSI and Hip Index could discriminate visceral adipose tissue from abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue53. Using NHANES 1999–2014, we found that an increase of 1 standard deviation in ABSI was associated with the increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 1.21, 95% CI 1.16–1.26), which is consistent with the result of a previous study11. In addition, an increase of 1 standard deviation in ABSI was associated with the increased risk of CVD-related mortality (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.14–1.35). All the subgroup analysis according to sex and comorbidities and analysis with PSM data also showed a significant association between the z score of ABSI and all-cause or CVD-related mortality (Supplementary table 1). These results provided additional evidence of ABSI being an effective prognostic factor for all-cause or CVD-related mortality in a large population.

LBSIZ is a modified abdominal obesity scale that in its simplest form transforms logged ABSI by subtracting its mean and dividing by its standard deviation (z-score of logged ABSI) but can be readily extendable to any divided group by gender and race. LBSIZ allows an easier calculation of cut-off values and clinical application14. A prospective cohort study conducted in Korea reported that LBSIZ was a better predictor of CVD than BMI or WC, and that the predictability of Framingham risk score for CVD events improved using LBSIZ18. In another population-based study using Korean NHANES data, LBSIZ showed a linear association with CVD54,55. Using US NHANES, LBSIZ showed a greater association with CVD compared with other parameters of obesity19. Moreover, in a study of the Korean and US NHANES, LBSIZ was suggested as a cost-effective measurement tool for the prediction of low muscle mass in populations with abdominal obesity56. Altogether, these results suggest that LBSIZ may be a useful tool that can complement BMI.

Herein, we showed that high body shape index value is a more accurate identifying risk for CVD and mortality than BMI. This study provides evidence that LBSIZ can be used to identify high-risk groups for mortality among individuals without obesity as defined by BMI. The strength of this study is its assessment of the association between body shape and mortality using longitudinal data of a representative sample. In addition, through a detailed analysis of CVD, we observed that LBSIZ may be a significant index for primary and secondary prevention of CVD mortality. We performed a detailed analysis through PSM on age, sex, and underlying diseases based on mortality and corrected the effects of confounding variables to show an association between each obesity index and mortality.

However, some limitations must be considered. First, we could not consider the effect of weight change on mortality because of lack of data. Second, we could not evaluate the beneficial effect of improvement in LBSIZ in terms of mortality. Third, we could not conduct the analysis by racial and ethnic minority groups because we could not calculate LBSIZ for them. NHANES categorized them in the other race group, which includes Asian and multi-racial. Although the LBSIZ equation for Asians has been previously reported19, there is no data for the multi-racial population. Considering the heterogeneity of this group, we excluded them from this study.

Conclusion

LBSIZ is positively correlated with all-cause and CVD mortalities. This finding is significant because it displays a different pattern from that of BMI, which showed U-shape association with mortality. Particularly, LBSIZ can be used to identify high-risk groups for mortality among individuals with low or normal BMI in both clinical practice and epidemiologic studies. Moreover, LBSIZ can compensate for the drawback of BMI, which could not distinguish muscle and fat. However, further prospective studies must be conducted to identify the beneficial effect of the improvement in LBSIZ on metabolic diseases and mortality.

Methods

Study population

NHANES data set from 1999 and 2014 were used in this study. Participants younger than 20 years of age with missing data (cardio-metabolic questionnaire, anthropometric or laboratory data) were excluded from the study. Out of 82,091 participants, 24,987 were included in this study (Fig. 1).

Measurements of obesity parameters

WC was measured at the upper lateral border of the iliac crest using a measuring tape in accordance with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 201257. BMI was defined as the value obtained by dividing weight (kg) by square of height (kg/m2).

LBSIZ was calculated by standardizing the WC values according to weight and height, based on the regression of logged WC on logged weight and logged height. The residuals from the respective estimation for each race were standard normalized to make LBSIZ, which is readily extendable to any divided group by including any categorical variables for race and gender in the regression. Simple formula and details are provided in the supplementary Excel file of the previous study14,19.

Measurements of covariates and outcomes

Covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and metabolic disorders, such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and CVD, at baseline. Data on age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking status, and alcohol consumption were obtained using a questionnaire. Hypertension was defined as follows: systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg, mean diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg, or treatment of hypertension. Diabetes using blood glucose level and HbA1c was defined as follows: fasting blood glucose level > 126 mg/dL, random blood glucose level > 200 mg/dL, HbA1c > 6.5%, or treatment of diabetes. Dyslipidemia was defined as fasting total cholesterol at 240 mg/dL or treatment of dyslipidemia.

A structured questionnaire was used to investigate the history of CVD events. Patients with one or more of the following were considered to have a history of CVD events: angina pectoris, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or cerebrovascular disease44.

Since the DEXA data were only available from 1999 to 2006 NHANES, 11,780 participants were included in the correlation analysis between obesity parameters and body composition. Appendicular skeletal mass was defined as the sum of the total fat-free mass excluding the bone mineral content of the limbs. ASMI was calculated by dividing the appendicular skeletal mass by the square of height2 (m2). Mortality data for NHANES were obtained from public-use linked mortality files at the National Center for Health Statistics based on a probabilistic match between NHANES and the National Death Index death certificates until December 31, 201558.

Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical variables of demographic characteristics, underlying diseases, anthropometric index, and blood test results are presented using mean with the standard deviation and frequency (%), respectively. Independent t-test and Pearson’s chi-squared test were conducted to compare the results. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to investigate the correlation between obesity parameters, ASMI, and total body fat percentage. Multiple Cox regression analysis was performed to assess the HRs for all-cause and CVD mortalities by adjusting for age, sex, race, smoking status, alcohol consumption, history of cancer, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and previous CVD events. Follow-up duration was calculated as the time from the first anthropometric and clinical measurements to death or last follow-up (December 31, 2015). Moreover, to control the possible bias arising from the confounding variables, PSM was carried out using a multiple logistic regression model according to the cutoff value of LBSIZ at the 75th percentile. The confounding variables selected for the PSM included age, sex, race, smoking status, alcohol consumption, history of cancer, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and previous CVD events. We utilized 1:2 matching by the nearest neighbor method with a caliber of 0.25 using R package “MatchIt”20. The graphical association between HR for each obesity parameter and mortality was evaluated using restricted cubic spline plots with four knots.

Statistical analysis was performed using International Business Machines (IBM) Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 3.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; www.r-project.org). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB No. HKS 2020-01-020). All U.S. NHANES protocols were approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (NCHS IRB/ERB Protocol Number: 1999–2004, Protocol #98–12; 2005–2010, Protocol #2005–06; 2011–2016, Protocol #2011–17). All patients provided written informed consent.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the CDC repository, [National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm].

References

World Health Organization. Fact sheet on obesity and overweight. [accessed 2018 May 13], Available from, http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (2017).

Solomon, C. G. & Manson, J. E. Obesity and mortality: A review of the epidemiologic data. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 66, 1044S-S1050 (1997).

Krauss, R. M., Winston, M., Fletcher, B. J. & Grundy, S. M. Obesity: Impact on cardiovascular disease. Circulation 98, 1472–1476 (1998).

Moon, S. et al. The influence of physical activity on risk of cardiovascular disease in people who are obese but metabolically healthy. PLoS ONE 12, e0185127 (2017).

Wallstrom, P., Bjartell, A., Gullberg, B., Olsson, H. & Wirfalt, E. A prospective Swedish study on body size, body composition, diabetes, and prostate cancer risk. Br. J. Cancer. 100, 1799–1805 (2009).

World Health Organization. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks (WHO Press, 2009).

Heymsfield, S. B., Scherzer, R., Pietrobelli, A., Lewis, C. E. & Grunfeld, C. Body mass index as a phenotypic expression of adiposity: Quantitative contribution of muscularity in a population-based sample. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 33, 1363–1373 (2009).

Romero-Corral, A. et al. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 32, 959–966 (2008).

Schneider, H. J. et al. The predictive value of different measures of obesity for incident cardiovascular events and mortality. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 1777–1785 (2010).

Flegal, K. M., Graubard, B. I., Williamson, D. F. & Gail, M. H. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA 293, 1861–1867 (2005).

Krakauer, N. Y. & Krakauer, J. C. A new body shape index predicts mortality hazard independently of body mass index. PLoS ONE 7, e39504 (2012).

Ji, M., Zhang, S. & An, R. Effectiveness of A Body Shape Index (ABSI) in predicting chronic diseases and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 19, 737–759 (2018).

Christakoudi, S. et al. A body shape index (ABSI) achieves better mortality risk stratification than alternative indices of abdominal obesity: results from a large European cohort. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 14541 (2020).

Chung, W., Park, C. G. & Ryu, O. H. Association of a new measure of obesity with hypertension and health-related quality of life. PLoS ONE 11, e0155399 (2016).

Dhana, K. et al. Association of anthropometric measures with fat and fat-free mass in the elderly: The Rotterdam study. Maturitas 88, 96–100 (2016).

Krakauer, N. Y. & Krakauer, J. C. Expansion of waist circumference in medical literature: Potential clinical application of a body shape index. J. Obes. Weight Loss Ther. 4, 216 (2014).

Krakauer, J. C. & Krakauer, N. Y. Combining body mass and shape indices in clinical practice. Case Rep. Med. 2, 1526175 (2016).

Moon, S., Park, J. H., Ryu, O. H. & Chung, W. Effectiveness of Z-score of log-transformed A Body Shape Index (LBSIZ) in predicting cardiovascular disease in Korea: the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study. Sci. Rep. 8, 12094 (2018).

Chung, W. et al. Utility of the Z-score of log-transformed A Body Shape Index (LBSIZ) in the assessment for sarcopenic obesity and cardiovascular disease risk in the United States. Sci. Rep. 9, 9292 (2019).

Ho, D., Imai, K., King, G. & Stuart, E. A. MatchIt: Nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J. Stat. Softw. 42(8), 1–28 (2011).

Uretsky, S. et al. Obesity paradox in patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease. Am. J. Med. 120, 863–870 (2007).

Bhaskaran, K., Dos-Santos-Silva, I., Leon, D. A., Douglas, I. J. & Smeeth, L. Association of BMI with overall and cause-specific mortality: A population-based cohort study of 3·6 million adults in the UK. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6, 944–953 (2018).

de Berrington Gonzalez, A. et al. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 2211–2219 (2010).

Romero-Corral, A. et al. Association of bodyweight with total mortality and with cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease: A systematic review of cohort studies. Lancet 368, 666–678 (2006).

Rahman, M. & Berenson, A. B. Accuracy of current body mass index obesity classification for white, black, and Hispanic reproductive-age women. Obstet. Gynecol. 115, 982–988 (2010).

Gurunathan, U. & Myles, P. S. Limitations of body mass index as an obesity measure of perioperative risk. Br. J. Anaesth. 116, 319–321 (2016).

Rothman, K. J. BMI-related errors in the measurement of obesity. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 32, S56–S59 (2008).

Coutinho, T. et al. Combining body mass index with measures of central obesity in the assessment of mortality in subjects with coronary disease: Role of “normal weight central obesity”. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61, 553–560 (2013).

Gastaldelli, A. et al. Metabolic effects of visceral fat accumulation in type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 2 (2002).

Donohoe, C. L., Doyle, S. L. & Reynolds, J. V. Visceral adiposity, insulin resistance and cancer risk. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 3, 12 (2011).

Shimizu, I., Yoshida, Y. & Minamino, T. Maintenance of subcutaneous fat homeostasis improves systemic metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Diabetes 64, 3984–3986 (2015).

Tran, T. T., Yamamoto, Y., Gesta, S. & Kahn, C. R. Beneficial effects of subcutaneous fat transplantation on metabolism. Cell Metab. 7, 410–420 (2008).

Arango-Lopera, V. E., Arroyo, P., Gutiérrez-Robledo, L. M., Pérez-Zepeda, M. U. & Cesari, M. Mortality as an adverse outcome of sarcopenia. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 17, 259–262 (2013).

Batsis, J. A., Mackenzie, T. A., Barre, L. K., Lopez-Jimenez, F. & Bartels, S. J. Sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity and mortality in older adults: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 68, 1001–1007 (2014).

Choi, K. M. Sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul, Korea) 28, 86–89 (2013).

Martone, A. M. et al. The incidence of sarcopenia among hospitalized older patients: Results from the Glisten study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 8, 907–914 (2017).

Castillo, E. M. et al. Sarcopenia in elderly men and women: The Rancho Bernardo study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 25, 226–231 (2003).

Atkins, J. L. et al. Sarcopenic obesity and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: A population-based cohort study of older men. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 62, 253–260 (2014).

Tian, S. & Xu, Y. Association of sarcopenic obesity with the risk of all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 16, 155–166 (2016).

Baumgartner, R. N. et al. Sarcopenic obesity predicts instrumental activities of daily living disability in the elderly. Obes. Res. 12, 199–2004 (2004).

Bener, A. et al. Obesity index that better predict metabolic syndrome: Body mass index, waist circumference, waist hip ratio, or waist height ratio. J. Obes. 2013, 269038 (2003).

Bays, H. Central obesity as a clinical marker of adiposopathy; increased visceral adiposity as a surrogate marker for global fat dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 21, 345–351 (2014).

Chan, J. M., Rimm, E. B., Colditz, G. A., Stampfer, M. J. & Willett, W. C. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care 17, 961–969 (1994).

Arnlöv, J., Ingelsson, E., Sundström, J. & Lind, L. Impact of body mass index and the metabolic syndrome on the risk of cardiovascular disease and death in middle-aged men. Circulation 121, 230–236 (2010).

Janssen, I., Katzmarzyk, P. T. & Ross, R. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79, 379–384 (2004).

Lee, D. Y., Lee, M. Y. & Sung, K. C. Prediction of mortality with a body shape index in young Asians: Comparison with body mass index and waist circumference. Obesity (Silver Spring) 26, 1096–1103 (2018).

Krakauer, N. Y. & Krakauer, J. C. Dynamic association of mortality hazard with body shape. PLoS ONE 9, e88793 (2014).

Krakauer, N. Y. & Krakauer, J. C. Association of X-ray absorptiometry body composition measurements with basic anthropometrics and mortality hazard. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 7927 (2021).

Hoermann, R., Fui, M., Krakauer, J. C., Krakauer, N. Y. & Grossmann, M. A body shape index (ABSI) reflects body composition changes in response to testosterone treatment in obese men. Int. J. Obes. 2005(43), 2210–2216 (2019).

Biolo, G. et al. Inverse relationship between “a body shape index” (ABSI) and fat-free mass in women and men: Insights into mechanisms of sarcopenic obesity. Clin. Nutr. 34, 323–327 (2015).

Gomez-Peralta, F. et al. Relationship between “a body shape index (ABSI)” and body composition in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 10, 21 (2018).

Krakauer, N. Y. & Krakauer, J. C. Association of body shape index (ABSI) with hand grip strength. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 6797 (2020).

Christakoudi, S., Tsilidis, K. K., Evangelou, E. & Riboli, E. Association of body-shape phenotypes with imaging measures of body composition in the UK Biobank cohort: Relevance to colon cancer risk. BMC Cancer 21, 1106 (2021).

Chung, W. et al. The association between Z-score of log-transformed A body shape index and cardiovascular disease in Korea. Diabetes Metab. J. 43, 675–692 (2019).

Chung, W. et al. Association of Z-score of the log-transformed A body shape index with cardiovascular disease in people who are obese but metabolically healthy: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2010. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 27, 158–165 (2018).

Moon, S., Kim, Y. J., Yu, J. M., Kang, J. G. & Chung, H. S. Z-score of the log-transformed A Body Shape Index predicts low muscle mass in population with abdominal obesity: The US and Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS ONE 15, e0242557 (2020).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Anthropometric Procedures manual. [Accessed 20 Feb 2018] Available from: URL: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/ n ch s/data /nh a nes /2011-2012/manuals/anthropometry_procedures_manual.pdf (2012)

Statistics, N. C. f. H.: Office of Analysis and Epidemiology. The Linkage of National Center for Health Statistics Survey Data to the National Death Index—2015 Linked Mortality File (LMF): Methodology Overview and Analytic Considerations. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Published 2019 (2019)

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Re-search Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (2020R1C1C1004999 to C.M.O.) and supported by “GIST Research Institute (GRI) IIBR” grant funded by the GIST in 2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design: S.M. and C.M.O. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: H.L., H.S.C., Y.J.K., M.K.C., Y.K.R., W.C., J.M.Y., S.M., and C.M.O. Drafting the work or revising: H.L., S.M. and C.-M.O. Final approval of the manuscript: H.L., H.S.C., Y.J.K., M.K.C., Y.K.R., W.C, J.M.Y., S.M., and C.M.O.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, H., Chung, H.S., Kim, Y.J. et al. Association between body shape index and risk of mortality in the United States. Sci Rep 12, 11254 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15015-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15015-x

This article is cited by

-

Evaluating the potential of waist-to-BMI ratio, a body shape index, and other anthropometric parameters in predicting cardiovascular disease mortality: evidence from NHANES III

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

Associations of four obesity indices with diabetes mellitus in Korean middle-aged and older adults using the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES)

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

The association between food insecurity and obesity, a body shape index and body roundness index among US adults

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Correlation and predictive value of novel anthropometric indicators with adult sarcopenia and sarcopenia obesity

Scientific Reports (2024)