Abstract

Evidence from previous epidemiological studies on the effect of physical activity on the risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is conflicting. We performed a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis to verify whether physical activity is causally associated with AD. This study used two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to estimate the association between physical activity (including overall activity, sedentary behavior, walking, and moderate-intensity activity) and AD. Genetic instruments for physical activity were obtained from published genome-wide association studies (GWAS) including 91,105 individuals from UK Biobank. Summary-level GWAS data were extracted from the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project IGAP (21,982 patients with AD and 41,944 controls). Inverse Variance Weighted (IVW) was used to estimate the effect of physical activity on AD. Sensitivity analyses including weighted median, MR-Egger, MR-PRESSO, and leave-one-out analysis were used to estimate pleiotropy and heterogeneity. Mendelian randomization evidences suggested a protective relationship between walking and AD (odds ratio (OR) = 0.30, 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.13–0.68, P = 0.0039). Genetically predicted overall activity, sedentary behavior, and moderate-intensity activity were not associated with AD. In summary, this study provided evidence that genetically predicted walking might associate with a reduced risk of AD. Further research into the causal association between physical activity and AD could help to explore the real relationship and provide more measures to reduce AD risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent cause of dementia1. AD is a kind of brain disease that happens to elder people and is responsible for the slow and gradual deterioration in thinking, memory, and language competence, and could also change the personality1. AD is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder in the world2.

There are 44 million individuals living with AD around the world according to the current estimate 3. The prevalence of AD in the European population is estimated at 5.05%4. The incidence of African Americans is approximately twice that among European Americans5. The United States, especially in the West and Southeast might experience the largest growth of AD cases and the number of AD patients could grow to 13.8 million by 2060 years6. The growing number of AD cases might cause a huge social-economic burden. Prevention of AD targeting risk factors modification has the potential to curb the increasing number of people living with AD and the increasing economic burden.

Observational studies had identified thirty-three percent of AD cases around the world might be due to several potentially modifiable risk factors after accounting for nonindependence between several risk factors, and the incidence might be decreased by using effective methods targeting to reduce the prevalence of modifiable risk factors such as physical inactivity7.

Compared to sedentary lifestyle, long-term exercise could delay the onset of physiological memory loss in middle-aged trained men8. Randomized clinical trials (RCT) also had been conducted to investigate whether interventions targeting inactivity could reduce the risk of AD, dementia, or cognitive function. A large and long-term RCT proved that physical activity could improve or at least maintain cognitive functioning in at-risk elder individuals9. An intervention study showed that physical activity could provide a modest improvement in cognition for individuals with subjective memory impairment as well10. Furthermore, previous meta-analyses including several RCTs also indicated that physical activity intervention showed a statistically significant improvement in cognition of patients diagnosed with AD or slow down the decline of cognition, and different amounts of physical activity can make different effects11,12. Additionally, physical activity might be associated with lowering the risk of AD based on a comprehensive meta-analysis13.

Though, other long-term RCTs had suggested that physical activity had no significant effects on cognitive decline or might not decrease the prevalence of all-cause dementia14,15. No difference in AD risk between physically active and inactive participants was observed in a meta-analysis including 19 prospective observational cohort studies16.

Understanding the relative contributions of physical activity to AD is crucial for designing suitable public health interventions to reduce the incidence of AD and decrease the socioeconomic burden. Using observational studies to determine the association might be challenging due to bias of measurement error, confounding, and reverse causation. Therefore, it remains to be elucidated whether the association between physical activity and AD is causal.

Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables could be conducted to explore whether the association between physical activity and AD is causal17. The study design is similar to RCT since genes are transferred from parents to offspring randomly17. All analyses reported in the present study are two-sample MR analyses since SNP-physical activity and SNP-AD associations were extracted from different rather than overlapping samples18. The main advantage of using summary-level data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in two-sample MR is the increased statistical power, particularly with testing effects on binary disease outcomes19.

In this study, we conducted the two-sample MR analysis using summary-level GWAS data on physical activity and AD to make a thorough inquiry about whether physical activity is causally linked with the risk of AD.

Method

Study design

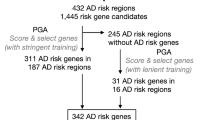

We conducted a two-sample MR analysis to explore the association between physical activity and AD. Genetic variants associated with physical activity were selected as genetic instruments for each exposure. The design of our study had three contents: (1) the acquisition of summary-level GWAS data for physical activity and AD; (2) the identification of genetic variants to serve as instrumental variables (IVs); and (3) the estimates of the effects of physical activity on AD.

Genetic associations with physical activity

Over 100,000 participants (mean age 57.52 years) from UK Biobank, a population-based prospective study20,21, who had provided valid email addresses were approached with a wear wrist-worn accelerometer, and 103,712 datasets were received with a median wear-time of 6.9 days (Supplementary Table 1)22. After quality control, a total of 91,105 participants of European descent remained for subsequent genome-wide association analysis and summary-level GWAS data used in the present analysis had been adjusted for BMI and sex as covariates23. A machine-learning model was used to predict four activity conditions including, sleep, sedentary behavior, walking, and moderate-intensity activity. For instance, sedentary behavior was defined as the energy expenditure score of Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) being less than 1.524. More information on genotyping and imputation is shown in Supplementary Method 1. Exposures of interest in our MR analysis were overall activity, walking, sedentary behavior, and moderate-intensity activity. We selected SNPs associated with overall activity, sedentary behavior, and walking at the genome-wide significance level (p < 5 \(\times\) 10–8). Only one SNP (rs568974867) was related to moderate-intensity activity at a genome-wide significance level (p < 5 \(\times\) 10–8). However, rs568974867 was not present in summary-level GWAS data of AD. Therefore, we set the threshold at a suggestive significance level (p < 5 \(\times\) 10–6) for moderate-intensity activity. We eliminated IVs which were associated with other genetic variants (r2 threshold < 0.1 and kb = 5,000).

Genetic associations with Alzheimer’s disease

Genetic associations with AD were obtained from the meta-analyses of GWAS on individuals of European ancestry (ncase = 21,982 and ncontrol = 41,944) contributed by the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project (IGAP). Details of IGAP were published elsewhere25. In brief, in stage 1, IGAP used genotyped and imputed data on 11,480,632 SNPs to meta-analyses GWAS datasets consisting of four consortia: the Alzheimer Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC); the European Alzheimer's disease Initiative (EADI); the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology Consortium (CHARGE); and the Genetic and Environmental Risk in AD Consortium Genetic and Environmental Risk in AD/Defining Genetic, Polygenic and Environmental Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium (GERAD/PERADES). Details of the above were shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Method 1. We inferred positive strand alleles by using allele frequencies to harmonize physical activity and AD data. We removed palindromic SNPs with intermediate allele frequency. More details on harmonization were shown in Supplementary Method 2. We did not use proxy SNPs in this research.

Statistical power calculation

Power calculations were conducted using an online web tool for the binary outcome available at https://sb452.shinyapps.io/power/)26. The statistical power for our MR relied on several parameters, including type I error of 1.25% after multiple testing corrections, the proportion of variance (R2) in the exposure explained by genetic instruments, the “true” causal effect of the physical activity on AD, and the ratio of cases to controls (1 to 1.908). More information is shown in Supplementary Method 3.

Statistical analysis

In the primary analysis, the fixed-effect inverse variance weighted (IVW) method was used to calculate the overall effects in the absence of heterogeneity27. However, if there is heterogeneity between the causal estimates of genetic variances, a random-effects model IVW would be conducted. Cochran’s Q statistic would be computed during MR analysis to estimate whether heterogeneity exists or not. The amount of heterogeneity also was estimated by I2 statistic28.

Sensitivity analysis

MR was based on three key assumptions29. Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the robustness of the MR results against any potential violation of the three key assumptions. Firstly, genetic variants must be associated with the exposure of interest. The strength of each instrument was measured using the F statistics calculated by the formula: F = R2(N − K − 1)/K(1 − R2), where R2 represented the variance in exposures explained by the genetic variance, K represented the number of instruments, and N meant the sample size of the GWAS for the association of the SNP-activity factors30. The instrumental variables should be strongly associated with exposures and F statistics of all the genetic variants should be larger than the empirical threshold of 1031. Secondly, genetic variants must not be associated with potential confounders of the association between the exposure and the outcome, which meant no horizontal pleiotropy. MR-Egger regression, which provided a statistical test for directional pleiotropy according to Egger intercept, was used to assess the potential presence of horizontal pleiotropy32. Though, if the Instrument Strength Independent of Direct Effect (InSIDE) assumption was violated, this estimate might increase type I error rates. Therefore, the weighted median estimator was used for sensitivity analysis. This estimate was consistent if up to half of the genetic variants (or variants comprising 50% of the weight for a weighted analysis) were valid IVs33. Additionally, we also conducted MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier (MR-PRESSO) analysis to explore the robustness of our results34. MR-PRESSO was a method to detect and correct outliers in IVW linear regression, which might reduce the heterogeneity in the estimates of causal effect by removing outliers. If the MR-PRESSO analysis indicated significant outliers exist, we would remove the outlier variants (with a P value less than the threshold in the MR-PRESSO outlier test) and conduct the MR analysis again. At the end of the analysis, a leave-one-out analysis was computed to test the robustness of MR estimates and whether anyone single variant was driving the causal association between exposure and outcome35. Thirdly, genetic variants should be associated with AD only through their effects on exposure, not through other pathways. The “negative control” population might be useful to evaluate the exclusion assumption36. Sensitivity analyses were not performed for walking as there were only 2 genetic variants.

Results were presented as log odds ratio for comparing with the rest (MET \(\le\) 1). The milli-gravity (mg) was used as a unit to report accelerometer-measured physical activity levels. An MR effect was considered significant at a Bonferroni-corrected P-value of 0.05/4 = 0.0125. A P-value < 0.05 but above the adjusted P-value was considered a suggestive association.

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Study in Epidemiology (STROBE) MR checklist is provided in Supplementary Information37. All analyses were performed with Two-Sample MR package 0.5.5 and MR-PRESSO package 1.0 in R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistic Computing, Vienna, Austria) (http://www.r-project.org/)34,38,39.

Ethical issues

Additional ethical approval was not required, since this study was based on MR analysis and depended on summary-level GWAS data rather than individual-level data, and the databases used in this analysis had been published or shared before.

Results

In total, we used 33 SNPs in this multi-instrument MR analysis. Detailed information on genetic variants used in this analysis was shown in Supplementary Table 2. F statistics for instruments for overall activity, sedentary behavior, and walking were larger than the empirical threshold of 10, demonstrating the small possibility of weak instrumental variable bias (Table 2). F statistics for the instrument for moderate-intensity physical activity was only 2.19, thus suggesting a weak instrument. The statistical power was only 45.3% for sedentary behavior, and the statistical power was between 80% to 1 for another three exposures, including overall activity, walking, and moderate-intensity activity (Table 2).

For overall activity, the random-effect IVW analysis was conducted later due to the heterogeneity (QP-val = 0.024). There was no significant association between genetically predicted overall activity and AD according to the result of IVW analysis (odds ratio (OR) = 0.62; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.17–2.32, P = 0.4805). However, the results computed by the weighted median method proved a suggestive association (OR = 0.35; 95% CI 0.13–0.92, P = 0.0362). There was an absence of directional pleiotropy according to MR-Egger regression (intercept = 0.19, 95% CI 0.05–0.33, P = 0.234). Besides, the MR estimate of ME-Egger was very different from others (OR = 0.00; 95% CI 0.00–0.14, P = 0.2207). The results of the null relationship were consistent before and after removing the outlier using MR-PRESSO (Table 3). Plots of leave-one-out analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1) demonstrated that there was potentially influential SNP driving the link between overall activity and AD. Therefore, we need to carefully interpret the result and draw a cautious conclusion. A Scatter plot was shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

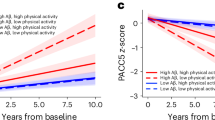

The result of random-effect IVW proved sedentary behavior might be associated with a higher risk of AD (OR = 1.33; 95% CI 1.23–1.43, P = 2.0188 \(\times\) 10–12) (Table 3, Fig. 1). Though fixed-effect IVW and weighted median analysis did not show evidence of a causal link. The MR-Egger intercept and MR-PRESSO did not show evidence of pleiotropy with sedentary behavior. Plots of leave-one-out analysis demonstrated no potentially influential SNPs driving the link between sedentary behavior and AD (Supplementary Fig. 1). A Scatter plot of SNP effects on exposure versus their effects on AD was shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

The IVW regression showed that an increase in walking time might decrease the risk of AD (OR = 0.30, 95% CI 0.13–0.68, P = 0.0039). The result was consistent with the random-effect IVW method (OR = 0.30; 95% CI 0.15–0.59, P = 0.0004). There was still a significant association after multiple testing corrections. The results were shown in Fig. 1. There was no heterogeneity according to Cochran’s Q test (P = 0.411) (Table 3). However, no other sensitivity analyses were conducted due to the limited number of IVs.

As for moderate-intensity activity, using 25 genetic instruments, linear MR analysis demonstrated no causal effects of moderate-intensity activity on AD risk (OR = 0.80; 95% CI 0.59–1.07, P = 0.1371), which was consistent with results in the weighted median method. Our analysis suggested no significant evidence of horizontal pleiotropy (as indicated by MR-Egger regression intercept close to zero and P = 0.450, Supplementary Fig. 2). The result of MR-PRESSO analysis indicated that no outliers existed (Table 3). The result of the leave-one-out analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1) showed potentially influential SNP driving the link between moderate-intensity activity. Results were shown in Fig. 1.

Discussion

In this two-sample MR analysis, we examined the effects of physical activity, including overall activity, sedentary behavior, walking, and moderate-intensity activity, on the risk of AD. Genetically predicted overall activity, sedentary behavior, and moderate-intensity activity were not associated with AD. Higher levels of walking might be beneficial for preventing AD.

For overall activity, the results of the IVW analysis (both fixed-effect and random-effect) suggested the absence of an association between exposure and AD. Nevertheless, the weighted median demonstrated a suggestive relationship. Besides, there was a huge difference between the effect sizes from IVW and ME-Egger analyses. While the MR-Egger estimate might be imprecise and influenced by outlying genetic variants, MR-PRESSO analysis did suggest outlier SNPs existed. There was still a null association between overall activity and AD when we excluded the potential outlier. Based on the different results drawn by sensitivity analyses, we should be cautious to conclude that overall activity does not influence the risk of AD.

There was no heterogeneity exiting for sedentary behavior according to Cochran’s Q statistic. We mainly focused on the MR estimate of the fixed-effect IVW method, which revealed a positive relationship between sedentary behavior and AD. Higher levels of sedentary behavior seemed related to a higher risk of AD, which indicated a deleterious effect of sedentary behavior on AD. However, consistent with the results of sensitivity analyses, the association was not significant. Sedentary behavior was defined as an activity that had a MET energy expenditure score of \(\le\) 1.5 and usually occurs at sitting, lying, and reclining status24. Nonetheless, other behaviors such as driving (MET < 2.5) and some instances of non-desk work were categorized as sedentary behavior in the original GWAS analysis which might be the explanation for the absence of association in our MR analysis23.

We found that the risk of AD decreases by proximately 30% for each 1-SD increase in genetically predicted walking levels. Although we only used 2 SNPs as instrumental variables for walking, these 2 SNPs explained a 0.12% variance in walking and they fulfilled the criterion of not being weak instrumental variables (F statistics > 10)31. Besides, the statistical power of the MR analysis for walking was sufficient. Therefore, low statistical power and weak instruments are unlikely to explain our results. However, sensitivity analysis could not be conducted to verify the independence and exclusion restriction assumption which might influence our results due to the limited number of SNPs.

The results of MR analysis did not demonstrate a relationship between moderate-intensity activity and AD. The null association might be influenced by a bias of weak instruments (F statistic = 2.19) due to violations of instrumental assumption. Secondly, even when using large samples (n = 91,105), results using weak instruments might be biased towards the null in the two-sample MR analysis36. That was also a well-powered MR result since moderate-intensity activity showed significant power (> 80%).

Our results were consistent with previous studies which suggested that physical activity was associated with a decreased AD risk13,40,41,42. The result from the previous analysis indicated exercise was related to a 28% decreased risk of AD was similar to our results13. The meta-analysis, which included 3345 participants had point estimates that suggested a protective effect of physical activity. The result of this meta-analysis finding an OR for the development of AD was 0.60 (95% CI 0.51–0.71) compared to inactive individuals40. Our study confirmed the finding of a clinical trial that suggested physical activity was associated with a reduced risk of AD (OR = 0.48; 95% CI 0.17–0.85)43.

The mechanism might be explained as follows: both animal and human research had shown that exercise resulted in beneficial changes to brain structure and function accompanying cognitive function44,45. Physical activity might modulate amyloid β (Aβ) turnover, inflammation, the synthesis and release of neurotrophins, and cerebral blood flow (CBF)46,47. Besides, activity can influence cognition through different pathophysiological processes such as the immune system, endothelial function, cerebrovascular insufficiency, oxidative stress, and neurotoxicity48.

It was worth mentioning that our results indicated walking rather than moderate-intensity activity is related to the reduced AD risk. The possible explanation might be the small sample size and the young age of subjects from previous research49. For AD, symptoms usually occurred after age 601. Secondly, the beneficial effect of an exercise intervention on cognitive function was driven by the types of activity50. Previous research might mix the effect of moderate-intensity activity with light and vigorous activity making it difficult to isolate the effects of moderate-intensity activity51,52. Further, moderate-intensity activity was defined by energy expenditure score in our MR analysis. The classification criteria for moderate-intensity activity in the previous research were inconsistent with the present MR analysis45. Apart from that, physical activity intervention in other research included not only aerobic exercise but also strength, and balance exercise42,53,54. The beneficial effect of moderate-intensity activity on cognitive function might pair with other elements. Our conclusion was supported by previous studies, which indicated that walking might enhance cognitive performance and suggested walking as little as 1.5 h weekly was beneficial for cognition in healthy elderly55. Furthermore, walking was not only positively correlated with emotional health, and memory, but also was beneficial for reducing depression scores, anxiety, and lower psychological stress56,57,58,59. Walking could even stabilize the progressive cognitive dysfunctions in AD patients60,61. Thus, we suggested that walking might be an effective strategy for AD prevention.

The results contrasted the finding of other studies that reported no difference in AD risk between physically active and inactive participants. The reasons for the difference between our MR analysis result and other research might be explained as follows. Firstly, previous studies could not exclude the potential effects caused by some biases, including unmeasurable confounders, reverse causality, and recall biases. Besides, for different randomized controlled trials, the intervention of physical activity or aerobic exercise and follow-up periods might be quite different. Moreover, there might be heterogeneity among these studies, especially in the different methods of measurement used for cognitive function. Secondly, most previous studies focused on the outcome of the cognitive improvement in people with AD or mild cognitive impairment, not the risk of incidence62,63. Thirdly, there were limited subjects in previous RCT studies64,65. Therefore, it would be hard to compare the effects of physical activity on AD risk.

Our results were contradictory to a previous MR study which suggested that physical activity did not affect the risk of development of AD66. The possible reason might be as follows: previous MR studies used moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MET \(\ge\) 6) as exposure, which might be different from the effects of daily activity. Physical activities were divided into more detailed categories, including sedentary behavior, walking, and moderate-intensity activity in the present MR analysis.

This study had several strengths. Firstly, daily physical activities including sedentary behavior and walking were recorded by activity trackers and were more precise than self-report data. Genetic variants identified in GWAS analysis based on self-reported data were at least partly influenced by reporting bias67,68. Secondly, based on the design of the present two-sample MR analysis, there might be less bias from confounding which would have been the case if both physical activity and AD GWAS were performed in the same sample. Thirdly, the influence of confounding factors on the studied association was reduced due to the strict selection of IVs. Fourthly, the previous MR analysis used average accelerations and the fraction of accelerations > 425 milligravities as exposure measures, the latter meaning vigorous physical activity (METs \(\ge\) 6) only66. More physical activity statuses were analyzed in our study. Besides, various methods, including IVW, MR-Egger, weighted-median, and MR-PRESSO were performed in this MR analysis to robust our conclusion. Finally, population stratification could be decreased in the present study as the AD dataset was restricted to participants of European ancestry.

Our study had certain limitations. Firstly, the GWAS of exposure consisted of participants aged 55–74 years with higher socioeconomic and physical health status, which might affect the results23. Besides, our results assumed that the sample used to define the IVs for physical activity and the samples from the IGAP consortium used to estimate the genetic association with AD are both from European ancestry. Hence, our results might not be suited to all populations. Thirdly, we cannot exclude the possibility of the sample overlap since both physical activity and AD used individuals from Europe. Therefore, that might generate bias in our analysis. A further limitation is that the number of genetic variants used for walking was limited for sensitivity analysis. Another limitation is that the studies included in IGAP used different diagnostic criteria for AD, but all cases met standard criteria for possible, probable, or definite AD. Hence certain misclassification might be inevitable. Sixthly, these exposure datasets recorded by wrist-worn accelerometer co-occur and interact across daily life. Multivariable MR analysis could be conducted to explore the relationship between physical activity and AD to make the results more precise69. Seventhly, the association between moderate-intensity activity and AD might be biased by weak instruments (F statistic = 2.19). Besides, the final MR assumption (the exclusion assumption) had not been evaluated. We did not search through the PhenoScanner to screen genetic variants which might be related to confounding factors70. We just conducted MR-PRESSO analysis to detect and remove outliers. We additionally calculated statistical power for our MR analysis. We had sufficient power to detect the effects of exposures on AD, except for sedentary behavior. Therefore, we should draw our conclusion with caution. Finally, the two-sample MR analysis assumed a linear relationship between physical activity and AD. In this research, we could not investigate the nonlinear effects of physical activity. Nevertheless, there could be a nonlinear relationship, such as U- or J- shaped association, between physical activity and AD. Therefore, further research could be needed to detect the causal factors of AD.

In summary, this study provided evidence that genetically predicted walking might associate with a reduced risk of AD. The elderly could use walking as the main way of commuting in daily life to reduce the risk of AD. Further research into the causal association between risk factors and AD could help to explore the real relationship and provide more measures to reduce AD risk. Mechanisms between physical activity and AD might need more investigation. More high-quality RCTs with fewer methodological issues and heterogeneity also are needed to back up our present findings.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study can be downloaded from [https://doi.org/10.5287/bodleian:yJp6zZmdj] and GWAS Catalog [http://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/gwas/summary_statistics/GCST007001-GCST008000/GCST007511/].

References

Watwood, C. Alzheimer’s Disease, 39. (DLPS Faculty Publications, 2011).

Ballard, C. et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 377, 1019–1031 (2011).

Lane, C. A., Hardy, J. & Schott, J. M. Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 25, 59–70 (2018).

Niu, H., Álvarez-Álvarez, I., Guillén-Grima, F. & Aguinaga-Ontoso, I. Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in Europe: A meta-analysis. Neurologia 32, 523–532 (2017).

Rajan, K. B., Weuve, J., Barnes, L. L., Wilson, R. S. & Evans, D. A. Prevalence and incidence of clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease dementia from 1994 to 2012 in a population study. Alzheimers Dement 15, 1–7 (2019).

Alzheimer’s Association. 2021 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement: J. Alzheimer's Assoc. 17, 327–406 (2021).

Norton, S., Matthews, F. E., Barnes, D. E., Yaffe, K. & Brayne, C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: An analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 13, 788–794 (2014).

De la Rosa, A. et al. Long-term exercise training improves memory in middle-aged men and modulates peripheral levels of BDNF and Cathepsin B. Sci. Rep. 9, 3337 (2019).

Ngandu, T. et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 385, 2255–2263 (2015).

Lautenschlager, N. T. et al. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: A randomized trial. JAMA 300, 1027–1037 (2008).

Jia, R. X., Liang, J. H., Xu, Y. & Wang, Y. Q. Effects of physical activity and exercise on the cognitive function of patients with Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 19, 181 (2019).

Du, Z. et al. Physical activity can improve cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Interv. Aging 13, 1593–1603 (2018).

Xu, W. et al. Meta-analysis of modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 86, 1299–1306 (2015).

Andrieu, S. et al. Effect of long-term omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation with or without multidomain intervention on cognitive function in elderly adults with memory complaints (MAPT): A randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 16, 377–389 (2017).

Moll van Charante, E. P. et al. Effectiveness of a 6-year multidomain vascular care intervention to prevent dementia (preDIVA): A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 388, 797–805 (2016).

Kivimäki, M. et al. Physical inactivity, cardiometabolic disease, and risk of dementia: An individual-participant meta-analysis. BMJ 365, l1495 (2019).

Smith, G. D. & Ebrahim, S. “Mendelian randomization”: Can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease?. Int. J. Epidemiol. 32, 1–22 (2003).

Burgess, S., Davies, N. M. & Thompson, S. G. Bias due to participant overlap in two-sample Mendelian randomization. Genet. Epidemiol. 40, 597–608 (2016).

Burgess, S., Scott, R. A., Timpson, N. J., Davey Smith, G. & Thompson, S. G. Using published data in Mendelian randomization: A blueprint for efficient identification of causal risk factors. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 30, 543–552 (2015).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: An open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

U. Biobank. Repeat Assessment: Participant Characteristics of responders vs. non-responders (2014).

Doherty, A. et al. Large scale population assessment of physical activity using wrist worn accelerometers: The UK Biobank Study. PLoS ONE 12, e0169649 (2017).

Doherty, A. et al. GWAS identifies 14 loci for device-measured physical activity and sleep duration. Nat. Commun. 9, 5257 (2018).

Tremblay, M. S. et al. Sedentary behavior research network (SBRN)—Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act 14, 75 (2017).

Kunkle, B. W. et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Abeta, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat. Genet. 51, 414–430 (2019).

Burgess, S. Sample size and power calculations in Mendelian randomization with a single instrumental variable and a binary outcome. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 922–929 (2014).

Burgess, S., Butterworth, A. & Thompson, S. G. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet. Epidemiol. 37, 658–665 (2013).

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560 (2003).

Greenland, S. An introduction to instrumental variables for epidemiologists. Int. J. Epidemiol. 29, 722–729 (2000).

Burgess, S. & Thompson, S. G. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 755–764 (2011).

Staiger, D. O. & Stock, J. H. Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. (1994).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: Effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 512–525 (2015).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G., Haycock, P. C. & Burgess, S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet. Epidemiol. 40, 304–314 (2016).

Verbanck, M., Chen, C.-Y., Neale, B. & Do, R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat. Genet. 50, 693–698 (2018).

Burgess, S., Bowden, J., Fall, T., Ingelsson, E. & Thompson, S. G. Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from Mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiology 28, 30–42 (2017).

Davies, N. M., Holmes, M. V. & Davey Smith, G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: A guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ 362, k601 (2018).

Skrivankova, V. W. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomization: The STROBE-MR statement. JAMA 326, 1614–1621 (2021).

Hemani, G. et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife 7, (2018).

Hemani, G., Tilling, K. & Davey Smith, G. Orienting the causal relationship between imprecisely measured traits using GWAS summary data. PLoS Genet. 13, e1007081 (2017).

Santos-Lozano, A. et al. Physical activity and alzheimer disease: A protective association. Mayo Clin. Proc. 91, 999–1020 (2016).

Iso-Markku, P. et al. Physical activity as a protective factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review, meta-analysis and quality assessment of cohort and case-control studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 56, 701–709 (2022).

Sattler, C., Erickson, K. I., Toro, P. & Schröder, J. Physical fitness as a protective factor for cognitive impairment in a prospective population-based study in Germany. J. Alzheimers Dis. 26, 709–718 (2011).

Rovio, S. et al. Leisure-time physical activity at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 4, 705–711 (2005).

Parachikova, A., Nichol, K. E. & Cotman, C. W. Short-term exercise in aged Tg2576 mice alters neuroinflammation and improves cognition. Neurobiol. Dis. 30, 121–129 (2008).

Marin Bosch, B. et al. A single session of moderate intensity exercise influences memory, endocannabinoids and brain derived neurotrophic factor levels in men. Sci. Rep. 11, 14371 (2021).

De la Rosa, A. et al. Physical exercise in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Sport Health Sci. 9, 394–404 (2020).

Müller, S. et al. Relationship between physical activity, cognition, and Alzheimer pathology in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 1427–1437 (2018).

López-Ortiz, S. et al. Physical exercise and Alzheimer’s disease: Effects on pathophysiological molecular pathways of the disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 2897 (2021).

Nakagawa, T. et al. Regular moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity rather than walking is associated with enhanced cognitive functions and mental health in young adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 614 (2020).

Groot, C. et al. The effect of physical activity on cognitive function in patients with dementia: A meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Ageing Res. Rev. 25, 13–23 (2016).

Scarmeas, N. et al. Physical activity, diet, and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA 302, 627–637 (2009).

Buchman, A. S. et al. Total daily physical activity and the risk of AD and cognitive decline in older adults. Neurology 78, 1323–1329 (2012).

Bohannon, R. W. & Crouch, R. Minimal clinically important difference for change in 6-minute walk test distance of adults with pathology: A systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 23, 377–381 (2017).

Lamb, S. E. et al. Dementia and physical activity (DAPA) trial of moderate to high intensity exercise training for people with dementia: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 361, k1675 (2018).

Weuve, J. et al. Physical activity, including walking, and cognitive function in older women. JAMA 292, 1454–1461 (2004).

Zhu, Z. et al. Exploring the relationship between walking and emotional health in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 8804 (2020).

Demnitz, N. et al. Cognition and mobility show a global association in middle- and late-adulthood: Analyses from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Gait Posture 64, 238–243 (2018).

Kelly, P. et al. Walking on sunshine: Scoping review of the evidence for walking and mental health. Br. J. Sports Med. 52, 800–806 (2018).

Vogt, T., Schneider, S., Brümmer, V. & Strüder, H. K. Frontal EEG asymmetry: The effects of sustained walking in the elderly. Neurosci. Lett. 485, 134–137 (2010).

Venturelli, M., Scarsini, R. & Schena, F. Six-month walking program changes cognitive and ADL performance in patients with Alzheimer. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dementias 26, 381–388 (2011).

Winchester, J. et al. Walking stabilizes cognitive functioning in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) across one year. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 56, 96–103 (2013).

Morris, J. K. et al. Aerobic exercise for Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized controlled pilot trial. PLoS ONE 12, e0170547 (2017).

Fonte, C. et al. Comparison between physical and cognitive treatment in patients with MCI and Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 11, 3138–3155 (2019).

Yu, F. et al. Cognitive effects of aerobic exercise in Alzheimer’s disease: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 80, 233–244 (2021).

Vidoni, E. D. et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on amyloid accumulation in preclinical Alzheimer’s: A 1-year randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 16, e0244893 (2021).

Baumeister, S. E. et al. Physical activity and risk of Alzheimer disease: A 2-sample mendelian randomization study. Neurology 95, e1897–e1905 (2020).

Klimentidis, Y. C. et al. Genome-wide association study of habitual physical activity in over 377,000 UK Biobank participants identifies multiple variants including CADM2 and APOE. Int. J. Obes. 42, 1161–1176 (2018).

Folley, S., Zhou, A. & Hyppönen, E. Information bias in measures of self-reported physical activity. Int. J. Obes. 42, 2062–2063 (2018).

Burgess, S. & Thompson, S. G. Multivariable Mendelian randomization: The use of pleiotropic genetic variants to estimate causal effects. Am. J. Epidemiol. 181, 251–260 (2015).

Staley, J. R. et al. PhenoScanner: A database of human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics 32, 3207–3209 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank the International Genomics of Alzheimer's Project (IGAP) for providing summary results data for these analyses. The investigators within IGAP contributed to the design and implementation of IGAP and/or provided data but did not participate in the analysis or writing of this report. IGAP was made possible by the generous participation of the control subjects, the patients, and their families. The i–Select chips were funded by the French National Foundation on Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. EADI was supported by the LABEX (laboratory of excellence program investment for the future) DISTALZ grant, Inserm, Institut Pasteur de Lille, Université de Lille 2, and the Lille University Hospital. GERAD/PERADES was supported by the Medical Research Council (Grant n° 503480), Alzheimer's Research UK (Grant n° 503176), the Wellcome Trust (Grant n° 082604/2/07/Z), and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF): Competence Network Dementia (CND) grant n° 01GI0102, 01GI0711, 01GI0420. CHARGE was partly supported by the NIH/NIA grant R01 AG033193 and the NIA AG081220 and AGES contract N01–AG–12100, the NHLBI grant R01 HL105756, the Icelandic Heart Association, and the Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University. ADGC was supported by the NIH/NIA grants: U01 AG032984, U24 AG021886, U01 AG016976, and the Alzheimer's Association grant ADGC–10–196728.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Z.: software, investigation, writing—original draft. X.H.: formal analysis. X.W.: methodology. X.C.: writing—review and editing. C.Z., G.W.: data curation. W.S.: software, visualization. W.Z.: supervision, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, B., Huang, X., Wang, X. et al. Using a two-sample mendelian randomization analysis to explore the relationship between physical activity and Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep 12, 12976 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17207-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17207-x

This article is cited by

-

Branched-chain amino acids and risk of major depressive disorder: a Mendelian randomization and colocalization study

Psychopharmacology (2025)

-

Identification of druggable genetic targets for prostate cancer risk based on mendelian randomization and single-cell RNA sequencing

International Urology and Nephrology (2025)

-

Physical activity and the risk of developing 8 age-related diseases: epidemiological and Mendelian randomization studies

European Review of Aging and Physical Activity (2024)

-

Causal Association Between Sedentary Behaviors and Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Mendelian Randomization Studies

Sports Medicine (2024)