Abstract

The critical magnetic induction (Bcr) values of a melt flow produced by a rotating magnetic field (RMF), remaining laminar or turbulent, are essential in different solidification processes. In an earlier paper (Metall Res Technol 100: 1043–1061, 2003), we showed that Bcr depends on the crucible radius (R) and frequency of the magnetic field (f). The effect of wall roughness (WR) on Bcr was investigated in this study. Using ten different wall materials, we determined the angular frequency (ω) and Reynolds number (Re) as a function of the magnetic induction (B) and f using two different measuring methods (pressure compensation method, PCM; height measuring method, HMM). The experiments were performed at room temperature; therefore, the Ga75wt%In25wt% alloy was chosen for the experiments. Based on the measured and calculated results, a simple relationship was determined between Bcr and Re*, f, R, and WR, where the constants K1, K2, K3, and K4 depended on the physical properties of the melt and wall material:

\(Bcr\left({Re}^{*},f,R,WR\right)=\frac{{Re}^{*}}{{R}^{2}}({K}_{1} {f}^{-K2}+{K}_{3} {f}^{-K4} WR)\)

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The microstructure of the solidified workpiece strongly depends on the melt flow, which evolves during the solidification. The cause of the melt flow might be the density difference between the different parts of the melt (buoyancy flow due to concentration and/or temperature difference) or stirring by magnetic induction (forced melt flow). The stirring by magnetic induction is extensively used at the solidification of different types of alloys and semiconductors, like the continuous casting of steels1,2,3. Both rotating magnetic field (RMF) and traveling magnetic field (TMF) can be implemented, but because the RMF facility is simpler, it is the most used technology.

During the last two decades, a lot of simulation was worked out to calculate the effect of forced melt flow on the solidified microstructure4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. For the validating of the simulation, one of the most usual methods is to prepare some unidirectional experiments using low melting point alloys with well-known solidification parameters with RMF (temperature gradient, solid/liquid front velocity, magnetic induction, and frequency) and compare the calculated values with the simulated one.

One of the most problematic parts of these simulations is validating the calculated angular velocity of melt flow. It is known that it is impossible to obtain the flow information inside the casting via plant trials and directly from the laboratory solidification experiments using model alloys of low melting point like aluminium.

The melt flow induced by the magnetic field might be laminar or turbulent, depending on the angular velocity. The effect of the laminar and the turbulent melt flow on the microstructure is different, so it is important to know the flow type in the simulation at a given induction (B) that forms during solidification.

As mentioned before, the forced melt flow due to the RMF directly affects the solidified microstructure (primary and secondary dendrite arm spacing, micro and macro segregation, grain structure, columnar/equiaxed transition)14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Suppose the angular velocity is higher, the effect also higher. The surface friction due to wall roughness (WR) decreases the angular velocity, so this effect on the microstructure will be smaller at a given magnetic induction.

For the effect of the RMF, many examples can be found in the literature. Unfortunately, we did not find experiments where the authors gave information about the wall roughness. In one experiment series, the authors used only one type of crucible with a constant WR, and we did not find the same (similar) experiments series with different.

The aim of these experiments is to show that if we want to compare the results of different experiments or the results of experiments with the results of simulations, it is substantial to determine the WR.

In an earlier study28, we demonstrated that the critical magnetic induction (Bcr) at which the melt flow remains laminar or becomes turbulent depends on the frequency and diameter of the crucible during the rotating magnetic field (RMF) stirring of the melt. In that case, a TEFLON crucible was used during the experiments, the wall of the crucible was assumed to be sufficiently smooth (the wall roughness was negligible), and there was no friction between the wall and melt (Samples 1 – 8 in Table 1). Many different crucible materials were used in the solidification experiments to study the effect of magnetic stirring on the solidified microstructure, e.g., aerogel15, graphite16,17,18, Al2O319,20,21,22,23, silica24, stainless steel25,26, gypsum27. The wall roughness of these crucibles was very different and was higher than that of TEFLON. The wall friction increased with an increase in wall roughness, and the angular velocity at a given magnetic induction (B) decreased. Therefore, Bcr was higher in the materials used in the solidification experiments15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. The comparability of the different experiments requires knowledge of the effect of wall friction on the melt flow. Many studies [e.g.,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 have investigated wall friction, but we did not find any information about this effect in the case of magnetic stirring of the melt. This study investigated this effect using extremely different wall roughness values. As the experiments were performed at room temperature, the Ga75In25 alloy was used from the usually used low melting temperature metals and alloys (Hg39, Ga 40,41, GaIn alloy42, GaInSn alloy43,44) in the case of this type of investigations.

Measuring methods

Pressure changes along the radius in a rotating liquid column as the liquid elements move at different velocities at positions with different radii. Consequently, a rotating paraboloid shape of the liquid surface develops in the case of a free surface (Fig. 1). There are two possibilities for determining the angular velocity of the metallic column developed by stirring the RMF.

(i) Measuring the change in the level of the free surface (height measuring method, HMM)45

The Δh = 2hin difference between the decrease at the centre and increase at the wall of the flat interface after a steady shape (Fig. 1) is obtained by calculating the angular velocity of rotation (see Eq. (1)). H is the height of the melt cylinder and position of the initial flat interface and R is its radius. In our experiments, the H/R aspect ratio changed between 60/5 = 12 and 60/12.5 = 4.8.

The angular velocity of the metallic column was calculated as follows:

A laser distance meter was used to measure the increase (hin) in the free surface of the metallic melt compared to the initial level, H, of the flat interface. The laser distance meter is illustrated in Fig. 2. The laser source (1 in Fig. 2) was fastened on an X -Y table. The laser was scanned on the bottom of the free surface, and the longest distance was accepted.

(ii) Measurement using the pressure compensation method (PCM)46

The pressure of the melt changes if the melt is rotated without a free surface, that is, in a closed tank. However, the pressure could be measured directly along the radius. A higher pressure corresponds to a larger radius. This phenomenon can be used to determine the average revolution number of the rotating melt stirred by an RMF. The pressure difference, Δp, related to the pressure prevailing at the axis of rotation can be calculated from the velocity differences of the melt elements that are present at any place with a radius of r. The peripheral speed was zero at the sample axis (r = 0), whereas the maximum value was at the crucible wall (r = R).

Measuring the pressure developing in the melt in the closed probe was difficult without disturbing the melt flow; therefore, the pressure was not measured directly in the closed probe. To perform the pressure measurement at r = R, the tank was closed with two gauges connections. The gauges at the axis (r = 0) and periphery (R) of the tank are labeled respectively ‘a’ and ‘b’ in Fig. 3a. The two gauges connections and tank were a ‘communication vessel.’ The melt level was the same at the gauge connections if the RMF inductor did not operate. Moreover, the atmospheric pressure was identical in the gauge connections, the so-called ‘stationary-level’ or ‘0-level’. As shown earlier1, the r = R − 0.2 mm position was chosen to measure the pressure because of the maximum pressure difference. Therefore, the relative error of the measured pressure was minimised.

A level difference of Δh developed between the melt levels in the ‘a’ and ‘b’ gauge connections when the melt was rotated (stirred) by the RMF inductor (Fig. 3b). The ρgΔh metal-static pressure of the melt column was in equilibrium with the pressure difference (Δp) that developed between the axis and periphery of the tank. If the free surface of the melt is at atmospheric pressure in the gauge connections, that is

The angular velocity (ω) of the metallic column can be calculated as follows:

To determine the pressure difference, the melt surface was returned to the ‘0’ level of the two gauges connections by supplying air at pressure Pcomp of the ‘b’ gauge with the pneumatic system. The accuracy of the pressure measurements was 20 Pa. As the measured pressure was higher than 20 Pa in most cases, this accuracy was sufficient. Details of the measurement and equipment are described elsewhere12.

Experiments

The Ga75wt%In25wt% alloy was chosen because the experiments were performed at room temperature. The physical parameters of the alloys are listed in Table 1. Two sets of experiments were performed (Table 2). Column 3 in Table 2 shows the methods used for the samples.

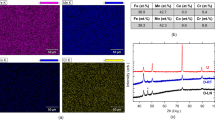

(i) Molten alloy was placed in a crucible (glass sample holder) with an internal diameter of 13 mm and a height of 100 mm. The height of the molten alloy ‘melt cylinder’ was 60 mm. The induction of the magnetic field was 72 mT, and the angular velocity of its rotation was 942 rad/s (the pole number of the three-phase inductor was two, and the frequency of its power-supply voltage was 150 Hz). During these experiments, six different values of the wall surface roughness (WR) were used on the internal surface of the sample holders. These different roughness values were achieved with oiled glass, dry glass, and glass covered with abrasive papers with a roughness corresponding to P150, P100, P60, and P40. The “PX” is the commercial mark of the abrasive paper (P means: paper). The difference between the abrasive papers is the diameter of the corundum (Al2O3) particles. The average diameter is 450, 280, 140, and 90 µm for the P40, P60, P100, and P150, respectively. The laser distance meter measured the value of WR of the different crucible walls was also used to measure the decrease (Δh) in the free surface of the metallic melt. Each 50th µm of the length of 3000 µm was measured. The average of the 60 measured values was the “0” line. After that, the average of the higher and lower length from the value of the “0” line was calculated. WR was characterised by the difference between these two average values. The values obtained in this manner are presented in Table 1. The oiled glass was considered to have a smooth surface, that is, its WR was 0 µm. The surface of the samples was investigated by SEM. Before the investigation, the samples were evaporated by Au, because the electrical conductivity of the samples is negligible. The SEM images were produced by secondary electrons (SE). The differences between the surfaces of the samples are shown in Fig. 4.

The thickness of the applied abrasive paper decreased the inside diameter of the sample holder by 3 mm (the thickness of the abrasive paper was approximately 1 mm, and the vent between the crucible wall and the abrasive paper was approximately 0.5 mm). The effective diameter of the crucible was 10 mm45.

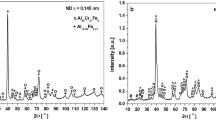

(ii) During the experiments, melt cylinders with radii of 5, 7.5, and 12.5 mm at frequencies of 50, 100, 150, and 200 Hz in a magnetic induction range of 0 – 90 were used. The height of the melt cylinder (H) was 100 mm. The radius of the melt cylinder (R) was smaller than the penetration distance in each case, except the case of 200 Hz and R = 12.5 mm. The crucible material was TEFLON1, ALOX, and the abrasive paper P4046. The H/R ratio changed between 100/5 = 20 and 100/12.5 = 8, thus, the influences of the penetration distance and ‘end effect’ on the measurement results were neglected.

Results and discussion

The results of the measured Pcomp(B) functions are shown in Fig. 5a (Samples 9 – 12) and Fig. 6a (Samples 13 – 16), and the measured Δh(B) function is shown in Fig. 7a (Samples 17 – 22). The angular frequency was calculated using Eq. 3 for Samples 9 – 12 (Fig. 5b) and Samples 13 – 16 (Fig. 6b). For Samples 17 – 22, only one Δh(B) point was measured at B = 72 mT (a big black point in the figure). From this data, ω(B = 72 mT) was calculated using Eq. 1, and the ω(B) function was calculated from B = 0 to B = 90 mT because the function is a straight line at B = 0 and ω = 0 (Fig. 7b). The Δh(B) function was calculated from these data. The angular velocities calculated using the PCM and HMM are compared in Fig. 7d. In the cases of Sample 17 (HMM) and Sample 9 (PCM method), the sample radius (R) and frequency of the magnetic induction (f) were the same (5 mm and 150 Hz), whereas the value of WR of Sample 9 was slightly higher than that of Sample 17 (0.04 and 0.0). As a result of this small difference, the values of the ω(B) function of Sample 9 were slightly smaller than those of Sample 17. In the cases of Sample 12 (PCM) and Sample 22 (HMM), R, f, and WR were the same, and the values of the two ω(B) functions were also the same. The main difference between the two methods was the friction between the melt and closing plate of the tank in the PCM. Comparing the results of the two methods, the effect was negligible.

Using the ω(B) functions, the Reynolds number (Re) as a function of magnetic induction (Re(B)) functions was calculated (Samples 9 – 12, Fig. 5c; Samples 13 – 16, Fig. 6c; and Samples 17 – 22, Fig. 7c):

where ν = 3.41 10−7 m2/s is the kinematic viscosity of the Ga75In25 alloy.

As the Re(B) function is a straight line in the investigated regime of magnetic induction (0 mT < B < 90 mT), the equation of this function is:

where m is the slope of the Re(B) function.

The Bcr values at which the flow in the melted alloy changed from laminar to unstable (at Re* = 2320) and from unstable to turbulent (at Re* = 4000)47,48,49 were determined using Eq. (6):

The Re(B) function and Bcr (Re* = 2320, Re* = 4000) values of Samples 1 – 8 were determined in an earlier study28. The calculated Bcr calc values using Eq. (6) are shown in columns 8 (Re* = 2320) and 10 (Re* = 4000) of Table 2. In this case, WR was 0.04 mm.

The Bcr values of the samples with R = 5 mm are shown as a WR function in Figs. 8a (f = 50 Hz) and Fig. 8b (f = 150 Hz). The Bcr(WR) functions are straight lines.

The slope of the Bcr(WR) function, Slo1, as a function of Re* is shown in Fig. 9. The Slo1(Re*) functions are again straight lines and depend on frequency. The slope of the Slo1(Re*) function, Slo2, is shown in Fig. 10. Based on these functions, the ΔBcr (R = 5 mm, Re*, f, WR) function is

The ΔBcr value at a given R:

Bcr(R, f, Re*, WR = 0) can be calculated from the measured value of Bcr(meas):

The type of the \(Bcr(R, f, Re*, WR=0)\) function is described in our earlier paper28:

Rearranging (Eq. 9):

Using the calculated values of Bcr (Re*, f, R, WR = 0) for all samples, this function is shown in Fig. 11. Based on the trendline:

and then

This equation differs slightly from Eq. (12) in28, where neither A nor n depends on Re* (n = − 0.628 at Re* = 2320 and n = − 0.695 at Re* = 4000).

Finally, the critical magnetic induction (Bcr) at a given Reynolds number (Re*) as a function of the sample radius (R), frequency (f), and wall roughness (WR) was calculated as follows:

In the case of a very smooth crucible (WR = 0), such as oiled glass, the laminar/unstable transition is:

and the unstable/turbulent transition is:

In the case of WR > 0, the laminar/unstable transition is:

and the unstable/turbulent transition is:

The measured (Bcr meas) and calculated (Bcr calc) values are compared in Fig. 12 and Table 2. For all 22 samples, R2 = 0.99; therefore, the agreement was suitable.

Using Eqs. (16 and 17), two plots were constructed to show the laminar/unstable and unstable/turbulent transitions at 50 and 150 Hz for WR = 0 (Fig. 13). These plots shown in Fig. 8 were similar to those in a previous study28. In this study, the differences considered the wall roughness of TEFLON (WR = 0.04 mm). The unstable range was very narrow at both 50 and 150 Hz.

In Fig. 14, the effect of wall roughness was demonstrated on the transients in the cases of 50 and 150 Hz. Wall roughness had a significant effect on transients.

Vortexes may have developed near the wall of the crucible, which can result in unstable or turbulent flow at a lower Bcr value than the calculated one. With the two measuring methods, this effect was not demonstrated; this method probably does not currently exist. Numerical simulation is the only method capable of studying this effect. In the case of the TEFLON crucible (WR = 0.04 mm), with numerical simulation, it was verified that near the crucible wall, the turbulent flow at a given magnetic induction while inside the flow remains laminar50.

Equations (13 – 17) are valid only for the Ga75In25 alloy, a maximum 12.5 mm radius, and a cylindrical sample. If the alloy, shape of the sample (e.g., rectangular), or the maximum radius is changed, the type of the \(Bcr(R, f, {Re}^{*}, WR)\) function will be the same, but the constants will change.

Summary

In a previous study1, the PCM was used. We showed that the angular frequency of the melt was significantly smaller than that of magnetic induction with RMF stirring. In this case, a TEFLON crucible with a relatively smooth surface was used during the experiments. The wall roughness can significantly change the wall friction and angular velocity of the melt flow. In practical solidification experiments, the wall roughness of the crucible material differed (rougher) from that of TEFLON. We must know the effect of the wall roughness to compare the different experiments and validate the melt flow simulations.

To obtain information about the effect of the wall roughness, we determined the angular frequency of the melt as a function of the magnetic induction (B) and the frequency (f) of the rotating magnetic field using two different methods (PCM and HMM). The crucible materials used were oiled and dry glass, two types of ALOX, TEFLON, and glass covered with abrasive papers with roughness corresponding to P150, P100, P60, and P40. The wall roughness, measured using a laser distance meter, was characterised by the average difference between the measured minimum and maximum distances. Based on the calculated Re number as a function of magnetic induction considering the wall roughness, we determined the magnetic inductions at which the flow changed from laminar to unstable and from unstable to turbulent.

Conclusion

(i) Two measurement methods (PCM and HMM) were used to determine the angular velocity of the melt. The measured angular frequencies were practically the same using the same experimental conditions for the two measuring methods (same magnetic induction and frequency, diameter, and crucible material).

(ii) The magnetic induction belonging to the laminar/unstable and unstable/turbulent transients (Bcr) were calculated using one equation as a function of the frequency of the magnetic field (f), critical Reynolds number (Re*), radius of the crucible (R), and roughness of the crucible wall (WR ):

where K1, K2, K3, and K4 are constants that depend on the physical properties of the melt (density, electrical conductivity, and kinematic viscosity).

(iii) If the wall roughness increases and Bcr belonging to the transients increases significantly, different experiments or melt flow simulations must be validated and performed.

(iv) The effect of the wall friction of TEFLON was minimal (WR = 0.04), as was previously proposed1.

(v) The wall roughness had a significant effect on the transients.

(vi) The unstable range was very narrow at 50 and 150 Hz.

(vii) Equations (13–17) were valid only for the Ga75In25 alloy, a maximum 12.5 mm radius, and a cylindrical sample. If the alloy, shape of the sample (e.g., rectangular), or radius changes, the type of the \(Bcr(R, f, {Re}^{*}, WR)\) function will be the same, but the constants will change.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- r :

-

The radius at a given point in the melt cylinder, mm

- R :

-

The radius of the melt cylinder, mm

- H :

-

The height of the melt cylinder, mm

- Δ p max :

-

The maximum pressure at r = R, Pa

- ρ :

-

Density of the melt, kg/m3

- ω :

-

Angular velocity of rotation (rad/s)

- g :

-

Gravitational constant, 9.81 m2/s

- h in :

-

Increase of the free surface at r = R, mm

- Δh :

-

the Difference between the decrease at the centre and increase at the wall of the flat interface, mm

- f :

-

The frequency of the RMF, Hz

- WR :

-

Wall roughness, mm

- Re :

-

The Reynolds number

- Re* :

-

Critical Reynolds number at laminar/unstable (2320) and unstable/turbulent transition (4000).

- RMF :

-

Rotating magnetic field

- B :

-

Magnetic induction of RMF, mT

- Bcr(meas) :

-

Measured critical magnetic induction at laminar/unstable and unstable/turbulent transitions, mT

- Bcr(calc) :

-

Calculated critical magnetic induction at laminar/unstable and unstable/turbulent transitions, mT

- ΔBcr :

-

Contribution of wall roughness to critical magnetic induction, mT

- K2, K3, K4, and K5 :

-

Are constants and depend on the physical constants of the melt (density, electrical conductivity, kinematic viscosity)

References

Kunstreich, S. Electromagnetic stirring for continuous casting - Part 2. Metall. Res. Technol. 100, 1043–1061. https://doi.org/10.1051/metal:2003113 (2003).

Stiller, J., Koal, K., Nagel, W. E., Pal, J. & Cramer, A. Liquid metal flows driven by rotating and traveling magnetic fields. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 220, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjst/e2013-01801-8 (2013).

Tzavaras, A. A. & Brody, H. D. Electromagnetic stirring and continuous casting — achievements, problems, and goals. JOM. 36, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03338405 (1984).

Wang, Y., Zhang, L., Chen, W. & Ren, Y. Three-dimensional macrosegregation model of bloom in curved continuous casting process. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 52, 2796–2805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-021-02231-5 (2021).

Zhang, H., Wu, M., Rodrigues, C. M. G., Ludwig, A. & Kharicha, A. Directional solidification of AlSi7Fe1 alloy under forced flow conditions: Effect of intermetallic phase precipitation and dendrite coarsening. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 52, 3007–3022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-021-06295-5 (2021).

Jiang, D. & Zhu, M. Solidification structure and macrosegregation of billet continuous casting process with dual electromagnetic stirrings in mold and final stage of solidification: A numerical study. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 47, 3446–3458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-016-0772-0 (2016).

Sun, H. & Zhang, J. Study on the macrosegregation behavior for the bloom continuous casting: model development and validation. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 45, 1133–1149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-013-9986-6 (2014).

Yu, H. Q. & Zhu, M. Y. Influence of electromagnetic stirring on transport phenomena in round billet continuous casting mould and macrostructure of high carbon steel billet. Ironmak Steelmak 39, 574–584. https://doi.org/10.1179/0301923312Z.00000000058(2012) (2012).

Guan, R., Ji, C. & Zhu, M. Modeling the effect of combined electromagnetic stirring modes on macrosegregation in continuous casting blooms. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 51, 1137–1153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-020-01827-7 (2020).

Liu, H., Xu, M., Qiu, S. & Zhang, H. Numerical simulation of fluid flow in a round bloom mold with in-mold rotary electromagnetic stirring. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 43, 1657–1675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-012-9737-0(2012) (2012).

Ren, B. Z., Chen, D. F., Wang, H. D., Long, M. J. & Han, Z. W. Numerical simulation of fluid flow and solidification in bloom continuous casting mould with electromagnetic stirring. Ironmak. Steelmak. 42, 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743281214Y.0000000240 (2015).

Fang, Q., Zhang, H., Wang, J., Liu, C. & Ni, H. Effect of electromagnetic stirrer position on mold metallurgical behavior in a continuously cast bloom. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 51, 1705–1717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-020-01849-1 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Experimental evaluation of MHD modeling of EMS during continuous casting. Met. Trans. B 53, 2166–2181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-022-02516-3 (2022).

Rerko, R. S., de Groh, H. C. & Beckermann, C. Effect of melt convection and solid transport on macrosegregation and grain structure in equiaxed Al–Cu alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 347, 186–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-5093(02)00592-0 (2003).

Steinbach, S., Euskirchen, N., Witusiewcz, V., Sturz, L. & Rake, L. Fluid flow effect on intermetallic phase in Al-cast alloys. Trans Indian Inst. Met. 60, 137–141 (2007).

Mikolajczak, P. Effect of rotating magnetic field on microstructure in AlCuSi alloys. Metals 11, 1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/met11111804 (2021).

Li, H., Chen, J. H., Zhang, P., Wang, T. & Li, T. Effect of rotating magnetic field on the microstructure and properties of Cu–Ag–Zr alloy Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 624, 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2014.11.064(2015) (2015).

Zou, J., Lu, D. P., Liu, K. M., Fu, Q. F. & Zhou, Z. Influences of alternating magnetic fields on the growth behavior and distribution of the primary Fe phase in Cu-14Fe alloys during the solidification process. Metals 8, 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/met8080571 (2018).

Lia, Y. Z., Mangelinck-Noël, N., Zimmermann, G., Sturz, L. & Nguyen-Thi, H. Comparative study of directional solidification of Al-7 wt% Si alloys in space and on Earth: Effects of gravity on dendrite growth and columnar-to equiaxed transition. J. Cryst. Growth https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2019.02.050 (2019).

Veres, Z., Roósz, A., Rónaföldi, A., Sycheva, A. & Svéda, M. The effect of melt flow induced by RMF on the meso- and micro-structure of unidirectionally solidified Al–7wt.% Si alloy benchmark experiment under magnetic stirring. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 103, 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2021.06.060 (2022).

Lu, Z. et al. Effect of a weak transverse magnetic field on the microstructures in directionally solidified Zn-22 at.% Cu peritectic alloy. ISIJ Int. https://doi.org/10.2355/isijinternational.ISIJINT-2016-433 (2017).

Qin, L., Shen, J., Feng, Z., Shang, Z. & Fu, H. Microstructure evolution in directionally solidified Fe–Ni alloys under traveling magnetic field. Mater. Lett. 115, 155–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2013.10.082 (2014).

Yu, J. et al. Influence of an axial magnetic field on microstructures and alignment in directionally solidified Ni-based superalloy. ISIJ Int. 57(2), 337–342. https://doi.org/10.2355/isijinternational.ISIJINT-2016-352 (2017).

Wang, L. et al. The effect of the flow driven by a travelling magnetic field on solidification structure of Sn–Cd peritectic alloys. J. Cryst. Growth. 356, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2012.07.014 (2012).

Matan, V., Eigenfeld, K., Rabiger, D. & Eckert, S. Grain size control in Al-Si alloys by grain refinement and electromagnetic stirring. J. Alloys Compd 487, 163–172 (2009).

Villers, B., Eckert, S., Michael, U. & Zouhar, G. The columnar-to equiaxed transition in Pb-Sn alloys affected by electromagnetically driven convection. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 402, 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2005.03.108 (2005).

Fragoso, B. & Santos, H. Effect of a rotating magnetic field at the microstructure of an A354. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2(2), 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2012.12.001 (2013).

Rónaföldi, A., Roosz, A. & Veres, Z. Determination of the conditions of laminar/turbulent flow transition using pressure compensation method in the case of Ga75In25 alloy stirred by RMF. J. Cryst. Growth. 564, 12607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2021.126078 (2021).

Scaggs, W. F., Taylor, R. P. & Coleman, H. W. Measurement and prediction of rough wall effects on friction factor—uniform roughness results. J. Fluids Eng. 110, 385–391. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3243568 (1988).

Flack, K. A. & Schultz, M. P. Roughness effects on wall-bounded turbulent flows. Phys. Fluids. 26, 101305. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4896280 (2014).

Li, G. et al. Effect of mechanical combined with electromagnetic stirring on the dispersity of carbon fiber in the aluminum matrix. Sci. Rep. 10, 8106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64983-5 (2020).

Schultz, M. P. & Myers, A. Comparison of three roughness function determination methods. Exp. Fluids. 35(4), 372–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-003-0686-x (2003).

J. Nikuradse, Laws of flow in rough pipes. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19930093938 (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, Technical Memorandum 1292, NACA TM 1292, Washington, 1950).

Colebrook, C. F. Turbulent flow in pipes, with particular reference to the transitional region between smooth and rough wall laws. J. Inst. Civil Eng. 11, 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2006.1939 (1939).

Moody, L. F. Friction factors for pipe flow. Transactions ASME 66, 671–684 (1944).

Schlichting, H. Experimental investigation of the problem of surface roughness, NACA TM 823 (1937)

Dvorak, F. A. Calculation of turbulent boundary layers on rough surfaces in pressure gradients. AIAA J. 7, 1752–1759. https://doi.org/10.2514/3.5386 (1969).

Granville, P. S. Three indirect methods for the drag characterization of arbitrarily rough surfaces on flat plates. J. Ship. Res. 31, 70–77 (1987).

Takeda, Y. & Kikura, H. Flow mapping of the mercury flow. Exp. Fluids 32, 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003480100296 (2002).

Wolz, M. P. & Mazuruk, K. An experimental study of the influence of a rotating magnetic field on Rayleigh-Bénard convection. J. Fluid Mech. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112001005341 (2001).

Brito, D. & Nataf, H. C. Ultrasonic Doppler velocimetry in liquid gallium. Exp. Fluids 31, 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003480100312 (2001).

Boden, S., Eckert, S. & Gerbeth, G. Visualization of freckle formation induced by forced melt convection in solidifying GaIn alloys. Mater. Lett. 64, 1340–1343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2010.03.044 (2010).

Rabiger, D., Eckert, S. & Gerbeth, G. Measurements of an unsteady liquid metal flow during spin-up driven by a rotating magnetic field. Exp. Fluids 48, 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-009-0735-1 (2010).

Wang, X., Fautrelle, Y., Etay, J. & Moreu, R. A periodically reserved flow driven by modulated traveling magnetic field: Part I. Experiments with GaInSn alloy. Met. Mat. Trans. B 40B, 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-008-9176-0 (2009).

Rónaföldi, A. Roósz, A. & Kovács, J. The influence of surface roughness of crucible's wall on the flow rate of melt stirred during solidification, IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 27 012049. http://iopscience.iop.org/1757-899X/27/1/012049. (2012).

Ronaföldi, A., Kovács, J. & Roósz, A. Revolution number (RPM) measurement of molten alloy by pressure compensation method. Mater. Sci. Forum. 649, 275–280. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.649.275 (2018).

Song, H. Engineering Fluid Mechanics, Jointly published with Metallurgical Industry Press, Springer, ISBN: 978–981–13–0172–8, https:// doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0173-5 (2018)

White, F. M. Fluid Mechanics (Mcgraw-Hill Series in Mechanical Engineering), 4th edn. ISBN 13: 9780070697164, ISBN 10: 0-07-228192–8 (McGraw-Hill Education, 1998).

Nagy, C., Rónaföldi, A. & Roósz, A. Comparison of measured and numerically simulated angular velocity of magnetically stirred liquid Ga-In alloy. Mater. Sci. Forum 752, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.752.157 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Hungarian National Research, Development, and Innovation Office for the subservience with the title of: “Formation of as-solidified structure and macrosegregation during unidirectional solidification under controlled flow conditions” and with the number of ANN 130946.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Miskolc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: A.R., A.R., Methodology: A.R., A.R., Hardware: A.R. Investigation: M.S., Z.V., Writing – Original Draft Preparation, A.R., Writing – Review & Editing: Z.V., M.S. Project Administration, Z.V. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roósz, A., Rónaföldi, A., Svéda, M. et al. Effect of crucible wall roughness on the laminar/turbulent flow transition of the Ga75In25 alloy stirred by a rotating magnetic field. Sci Rep 12, 18592 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21898-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21898-7