Abstract

Lung cancer accounts for the most cancer-related deaths in the world. Our previous study suggested the improved survival of lung cancer patients, mainly female patients, with subsequent metachronous primary breast cancer. However, whether the survival advantages of the two primaries are associated with patients’ sex and the specific breast cancer is unclear. Whether male lung cancer patients with another primary may encounter the same survival advantage as female patients is also uncertain. The uncertainty hinders these patients from the potential benefit of lung cancer clinical trial. A total of 343 male lung adenocarcinoma patients with subsequent bladder papillary transitional cell carcinoma (LCBC), 1539 lung adenocarcinoma patients with prior bladder papillary transitional cell carcinoma (BCLC), 1181 lung adenocarcinoma patients with subsequent prostate adenocarcinoma (LCPC), 7426 lung adenocarcinoma patients with prior prostate adenocarcinoma (PCLC), and patients with single bladder/prostate/lung (SLC) cancer were identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results. Patients were classified into simultaneous two primary cancer (sTPC), metachronous two primary cancer 1 (mTPC1), or mTPC2 groups when interval time between two cancers was within 6 months, between 7 and 60 months, or over 60 months, respectively. Propensity matching score program was executed to match the two primary cancers with single primary. Cox regression and competing risk regression were performed to identify confounders associated with all-cause and cancer-specific survival, respectively. The major cancer-related and non-cancer-related death in the two primaries were lung cancer and heart disease, respectively. Median overall survival times since lung primary of LCBC and SLC were 97 and 17 months, respectively, and incidence of all-cause and cancer-specific death in LCBC since lung malignancy was significantly lower (Coef. − 1.24, 95% CI − 1.49 to 0.99; SHR 0.42, 95% CI 0.33–0.53). Among the categorized groups, prognosis values of sTPC and mTPC2 groups were not statically different from that of the matched single lung cancer, whereas increased overall survival time and decreased incidence of all-cause and cancer-specific death relative to the matched patients were observed in mTPC1 group (H.R 0.28, 95% CI 0.19–0.41; SHR 0.33, 95% CI 0.23–0.47). Similar prognosis of LCPC relative to SLC was also observed. Furthermore, a generally improved survival relative to SLC was observed in PCLC (median survival times of PCLC and SLC were 17 and 12 months, respectively; Coef. − 0.32, 95% CI − 0.43 to 0.22; SHR 0.77, 95% CI 0.69–0.85), whereas prognosis of BCLC was similar to the matched ones. These results hinted that survival of lung cancer patients might vary with prior cancer history. Further analysis among groups with the two primaries suggested that advanced bladder cancer was not associated with prognosis of patients with LCBC and BCLC. On the contrary, advanced prostate cancer was associated with all-cause and cancer-specific death in patients with PCLC but not in patients with LCPC. Compared with patients with single lung cancer, male lung cancer patients with subsequent bladder/prostate primary over 6 months experienced generally improved survival. These results were similar to our previous study regarding female lung cancer patients with another breast primary. On the contrary, male lung cancer patients with prior primary malignancy encountered varied prognosis: improved survival relative to single lung primary was observed in lung cancer with prior prostate cancer, whereas prognosis of lung cancer with prior bladder cancer was not different. Therefore, great attention was required to characterize prognosis of lung cancer patients with another primary in advance, which was essential to eliminate the potential bias when these patients were included into the clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Great progress has been made in many cancers’ treatment in recent years. However, patients with lung adenocarcinoma still encounter poor prognosis, and these patients may simultaneously/metachronously suffer from another primary cancer1. In consideration of multiple cofactors associated with survival, prognosis of the two primaries are poorly known. Moreover, studies targeting lung cancer barely include the two primaries, but some works suggested that risk of potential bias due to the involvement of the two primaries is exaggerated2,3,4. This conclusion is difficult to draw due to the complex influences involved and the lack of population-based evidence. Our previous report suggests that, compared with patients with single lung cancer and lung cancer with prior/subsequent primary breast cancer within 6 months, lung cancer patients, mainly female, with subsequent breast cancer over 6 months encounter improved survival5. However, whether the survival advantages of the two primaries is associated with patients’ sex and specific breast cancer is unclear. Whether male lung cancer patients with another primary may encounter the same survival advantage as female patients is also uncertain.

For male patients, the risk of malignancies in urinary system is higher than that in other anatomical sites: incidence of papillary transitional cell carcinoma in bladder (PTCB) and adenocarcinoma in prostate (ACPS) is estimated at 8.6% and 33.10% in 20216,7, respectively. Meanwhile, ratio of PTCB/ACPS in male lung cancer patients with another primary is reported to be higher than that with other malignancies either, which is similar to breast cancer in female lung cancer patients8. However, studies focusing on the majority of male two primaries are limited. Missing information of patients’ survival hinders the profound appeal to promote the involvement of these patients into the clinical lung cancer trials.

With data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database of the National Cancer Institute (SEER), this study was designed to depict survival of male lung cancer patients with another bladder/prostate cancer relative to single primary, as well as the cofactors associated with prognosis since lung malignancy.

Materials and methods

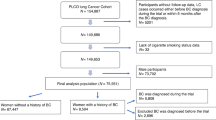

Medical records between January 1975 to December 2018 were identified from SEER by SEER*Stat software version 8.3.5 (accession number: 12223-Nov2018). International Classification of Diseases for Oncology Site Recode (third edition, ICD-O-3), rule of international multiple primary cancers, and SEER historic stage were applied to characterize the anatomical site, records of two primary cancers, and clinical stages (localize, regional, distant, and unknown), respectively. Notably, localized and regional stage of prostate cancer were not distinguished from each other in SEER database. Basic information (race, sex, year and age at diagnosis, insurance, and marital status) and cancer-related information (histology, site, clinical stage, surgical and radiation status, survival time, and cause of death) were selected either. Based on the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th Revision), cause of deaths such as prostate-, bladder-, and lung-related deaths were considered interested ones, whereas events such as heart disease- and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-related deaths were considered competing ones9. Chemotherapy was excluded due to that the information was missing in most records. After incomplete medical records, only autopsy or death certificate, and female patients were removed, 343 male lung adenocarcinoma patients with subsequent bladder papillary transitional cell carcinoma (LCBC), 1539 lung adenocarcinoma patients with prior bladder papillary transitional cell carcinoma (BCLC), 1181 lung adenocarcinoma patients with subsequent prostate adenocarcinoma (LCPC), 7426 lung adenocarcinoma patients with prior prostate adenocarcinoma (PCLC), 120,237 patients with single bladder papillary transitional cell carcinoma, 941,818 patients with single prostate adenocarcinoma, and 136,514 patients with single lung adenocarcinoma were identified (Tables 1, s1).

The sequence of primary cancers was determined by sequence number as reported10. Briefly, simultaneous two primaries (sTPC), metachronous two primary primaries (mTPC1), or mTPC2 were determined when the interval times between first and secondary primary cancers were within 6 months, between 7 and 60 months, or over 60 months, respectively. To reduce the unknown factors, such as medical progress with years, year of malignant diagnosis was classified into three groups: before 1995, between 1995 and 2005, and after 2005. Propensity matching score (PSM) program was executed to evaluate survival of the two primary cancer patients relative to single lung/bladder/prostate cancer. In brief, PSM with 1:1 ratio without replacement was performed between selected records of two primaries and single lung/prostate/bladder cancer. Briefly, caliper size was set at 0.1 and command psestimate was executed for covariates including race, year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, insurance and marital status, as well as surgery and radiotherapy, to achieve optimal imitative effect. Next, command psmatch2 was executed with the selected linear or quadratic function of covariates and command pstest was executed to determine whether the absolute standardized difference between matched covariates was within 10% (s20 tab- s51 tab). Notably, for secondary cancer in records with two primaries and first cancer in sTPC group, all selected corresponding single primary were involved in the PSM program; for first cancer in mTPC1 group, the matched single cancers were required to survival at least 6 months; for first cancer in mTPC2 group, the single cancers were required to have a survival time of over 60 months.

All-cause survival of cancer patients was determined via median survival time, which was obtained via the Kaplan–Meier mode. Cox proportional hazard regression model with explanatory factors, such as clinical stage, age at diagnosis, and surgical and radiation status, was performed to identify factors associated with all-cause death. Proportional hazard assumption after Cox regression was tested and regression model was considered to fit the assumption if p value was over 0.05. For p value below 0.05, time-dependent Cox regression was subsequently performed to analyze the cofactors associated with survival. Competing risk modes (Fine and Gray’s competing risk regression modes) was applied to identify cofactors associated with cancer-specific death. Other variables such as race, sex, first and secondary marital/insurance status, and clarified diagnosis-year were included in the modes if p of univariate analysis of the indicated variable was less than 0.15.

The statistical analyses were performed using STATA. To reduce type I error after multiple comparisons, p value of cofactors associated with survival was adjusted by Benjamini–Hochberg program and p value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. In consideration of the retrospective nature of this study, informed consent of patients was exempted.

Results

Basic information

Among the selected records, the median ages of diagnosed lung malignancy in LCBC, BCLC, LCPC, and PCLC were 70, 75, 67, and 75, respectively; median interval times between two primaries were 21, 55, 21, and 62 months. Localized, regional, distant, and unknown stage of lung primary accounted for proportions of 36.15%, 27.41%, 20.41%, and 16.03% in LCBC, respectively; on the contrary, they accounted for proportions of 18.71%, 18.00%, 48.93%, and 14.36% in BCLC. For patients with LCPC, the proportions of localized, regional, distant, and unknown stage of lung primary were 34.12%, 23.54%, 17.27%, and 25.06%, respectively; by contrast, the proportions were 17.10%, 18.85%, 51.91%, and 12.13% in patients with PCLC. The major cancer-related deaths in identified two primaries, single prostate cancer, single lung cancer, and single bladder cancer were lung cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, and bladder cancer, respectively; on the contrary, the major non-cancer-related death in identified two primaries and single primaries was heart disease (Tables 1, s1).

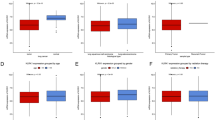

Prognosis relative to single primary

Prognosis of lung cancer patients with another primary relative to the single lung primary has drawn great attention. Therefore, survival times of LCBC, BCLC, LCPC, and PCLC were subsequently matched with single primary malignancy via PSM program. A total of 696 patients with LCBC or single lung cancer were included in the cohort. Median overall survival times since lung primary of LCBC and single lung cancer were 97 and 17 months, respectively (Table 2). Incidence of all-cause and cancer-specific death of LCBC since lung malignancy was significantly lower than that of matched single primary (Coef. − 1.24, 95% CI − 1.49 to 0.99; SHR 0.42, 95% CI 0.33–0.53). When categorized by interval time, prognosis values of sTPC and mTPC2 groups were not statically different from that of matched single lung cancer (sTPC group: H.R 0.94, 95% CI 0.66–1.32; SHR 1.01, 95% CI 0.73–1.41; mTPC2 group: H.R 0.55, 95% CI 0.26–1.14; SHR 0.69, 95% CI 0.33–1.44). By contrast, increased overall survival time and decreased incidence of all-cause and cancer-specific death relative to the matched patients were observed in mTPC1 group (H.R 0.28, 95% CI 0.19–0.41; SHR 0.33, 95% CI 0.23–0.47.). For BCLC and matched single lung cancer, median overall survival times were 14 and 13 months, respectively (Table 2); incidence of all-cause and cancer-specific death was generally not different from each other (H.R 0.92, 95% CI 0.80–1.05; SHR 0.87, 95% CI 0.76–1.00). Meanwhile, overall survival time of LCBC and BCLC was generally shorter than that of matched single bladder cancer, and incidence of all-cause and cancer-specific death in the two primaries was higher than the matched ones either (Tables s2–s9).

Median overall survival times of LCPC and single lung cancer involved in the cohort form PSM analysis were 116 and 16 months, respectively (Table 3); incidence of all-cause and cancer-specific death in LCPC was lower than that in corresponding lung cancer (Coef. − 1.31, 95% CI − 1.46 to 1.15; SHR 0.40, 95% CI 0.35–0.47). Further analysis suggested that prognosis of sTPC group was not statically different from that of matched single lung cancer (H.R 0.97, 95% CI 0.79–1.19; SHR 1.04, 95% CI 0.84–1.27); by contrast, survival times of mTPC1 and mTPC2 groups were improved (mTPC1 group: Coef. − 1.40, 95% CI − 1.62–1.18; SHR 0.32, 95% CI 0.26–0.40; mTPC2 group: Coef. − 0.90, 95% CI − 1.35 to 0.44; SHR 0.54, 95% CI 0.35–0.85). These results were similar to that from LCBC. Interestingly, further regression analysis suggested that PCLC generally encountered an improved survival relative to the corresponding single lung cancer (median survival times of PCLC and SLC were 17 and 12 months, respectively; PCLC vs. SLC: Coef. − 0.32, 95% CI − 0.43 to 0.22; SHR 0.77, 95% CI 0.69–0.85). However, prognosis values of LCPC and PCLC were generally inferior to that of matched single prostate cancer (Tables 3, s10–s16, Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Survival analysis among sTPC, mTPC1, and mTPC2 groups

The median overall survival times since lung malignancy in patients with LCBC and BCLC were 103 and 11 months, respectively. The median overall survival times since lung primary of sTPC, mTPC1, and mTPC2 groups were 16, 92, and 345 months, respectively, among patients with LCBC; by contrast, the times were 18, 12, and 10 months among patients with BCLC (Table s17). After cofactors such as age and stage were adjusted, incidence of all-cause and cancer-specific death in sTPC group was significantly higher than that in mTPC1 and mTPC2 groups with LCBC (mTPC1 vs. sTPC: Coef. − 1.68, 95% CI − 2.07 to 1.29; SHR 0.25, 95% CI 0.17–0.37; mTPC2 vs. sTPC: Coef. − 3.04, 95% CI − 3.67 to 2.41; SHR 0.11, 95% CI 0.06–0.21); on the contrary, sTPC group was insignificantly different from mTPC1 and mTPC2 groups with BCLC (mTPC1 vs. sTPC: Coef. 0.09, 95% CI − 0.12 to 0.31; SHR 1.10, 95% CI 0.90–1.35; mTPC2 vs. sTPC: Coef. 0.16, 95% CI − 0.05 to 0.38; SHR 1.15, 95% CI 0.95–1.41). In detail, advanced bladder cancer was not associated with all-cause and cancer-specific death since lung cancer in patients with LCBC and BCLC. Interestingly, lung-surgery (vs. no surgery) was associated with improved prognosis in LCBC and BCLC, whereas advanced lung cancer was associated with poor prognosis of BCLC but not with that of LCBC (Table s18).

Meanwhile, median survival times since lung malignancy in patients with LCPC and PCLC were 137 and 12 months, respectively. In detail, sTPC, mTPC1, and mTPC2 groups with LCPC experienced 13, 129, and 319 months of median overall survival, respectively; by contrast, the times were 16, 12, and 11 months in patients with PCLC (s17 tab). Similar to the analysis of LCBC and BCLC, prognosis of sTPC group with LCPC was much inferior to that of mTPC1 and mTPC2 groups (mTPC1 vs. sTPC: Coef. − 1.40, 95% CI − 1.61 to 1.19; SHR 0.35, 95% CI 0.27–0.45; mTPC2 vs. sTPC: Coef. − 2.50, 95% CI − 2.84 to 2.17; SHR 0.18, 95% CI 0.13–0.25). For patients with PCLC, incidence of all-cause death since lung primary in sTPC group was lower than that in mTPC1 and mTPC2 groups, whereas cancer-specific death was not different (mTPC1 vs. sTPC: Coef. 0.17, 95% CI 0.06–0.27; SHR 1.09, 95% CI 0.98–1.22; mTPC2 vs. sTPC: Coef. 0.21, 95% CI 0.10–0.32; SHR 1.08, 95% CI 0.96–1.21). Advanced prostate cancer was associated with all-cause and cancer-specific death for patients with PCLC but not for patients with LCPC. Meanwhile, advanced stages of lung cancer and no surgery (vs. surgery) were associated with worse prognosis of LCPC and PCLC (s19 tab).

Discussion

In this study, we depicted survival of male lung cancer patients with another primary bladder/prostate cancer relative to single primary and characterized cofactors associated with the prognosis of the two primaries since lung malignancy. Compared with single lung cancer, lung cancer with subsequent bladder cancer over 6 months and lung cancer with prior prostate cancer experienced increased median overall survival time and decreased incidence of all-cause and cancer-specific death; by contrast, the remaining encountered no statically different survival. Further analysis suggested the improved survival of mTPC1 and mTPC2 groups relative to sTPC group since lung primary in lung cancer with subsequent bladder/prostate cancer, whereas survival of mTPC1 and mTPC2 groups was not statically different from that of sTPC group in lung cancer with prior bladder cancer. Meanwhile, prognosis of the two primary patients was generically poorer than that of single bladder/prostate cancer patient. To our knowledge, this study is the first population-based systematic work of survival of male lung cancer patients with another primary bladder/prostate cancer.

Lung cancer is one of most common malignancy following urinary cancer, but studies of the two primary patients are limited. Zhou et al. reported that lung cancer patients with prior bladder/prostate cancer generally experienced inferior survival to patients without prior cancer10. Laccetti et al. reported that lung cancer patients with prior bladder cancer had no worse survival compared with patients without prior cancer history11,12,13,14. These results are conflicting, and the number of patients involved in Laccetti’s report is greater (patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2008 vs. 1992 and 2009). In this study, we included entire records with primary lung and bladder/prostate cancers linked in SEER database. We also excluded the potential bias such as medical progress accompanying with years at beginning of PSM program. Our results suggested all-cause and cancer-specific survival of lung cancer patients with prior bladder is similar to that of patients without prior bladder history, which is in consistent with Laccetti’s report and the draft guidance from the Food and Drug Administration either15. However, the generally improved survival of lung cancer with prior prostate cancer may complicate the results when the two primary patients were involved in the lung-clinical trial. Mechanisms mediating the survival advantage remains to be uncovered, and more data are required to interpret these results.

Meanwhile, information about prognosis of lung cancer with subsequent bladder/prostate cancer is scarcer, which may be attributed to its rareness. Our analysis suggested the time dependent impact of subsequent bladder/prostate cancer over prognosis of the two primary cancer patients: the prognosis may be better when the interval between first and secondary primary is longer5. These results are similar to that of female lung cancer with subsequent breast cancer, which may be attributed to the aggressive nature of secondary malignancy with prior early-stage cancer and more frequent follow-up associated lead- and length-time biases3. Another possible reason is an advantageous lung cancer phenotype in survivors with metachronous bladder/prostate, which is reported to be a better responder to local and systemic therapy16,17,18. Moreover, the common pathways among lung, bladder, and prostate cancers are another reason19. Therefore, drugs such as cisplatin during bladder chemotherapy may simultaneously target the lung cancer cells. More studies are required to reveal mechanisms mediating survival advantage of lung cancer patients with subsequent bladder/prostate cancer over 6 months.

The limitation of this study included several dimensions. First, information associated with patients’ prognosis such as chemotherapy for lung/bladder/prostate cancer, smoking history, and economic status was missing in the database, which might affect the results. However, the consistency of Cox analysis among the two primary cancer patients and PSM matching program between two primary cancer and single primary supported of the soundness of our results. Second, although this study was based on a national database, the number of records qualified for this study, especially for patients with LCBC, was still limited. This limitation may contribute to the bias in the stratified survival of two primaries. For example, survival of male lung cancer patients with subsequent bladder over 60 months (only 60 qualified records) is not statically different to that of matched sing lung primary, which was greatly improved compared with that of simultaneous lung and bladder primaries. Finally, bias was inevitable due to the properties of a retrospective epidemiological study.

Overall, our analysis suggested that prognosis of lung cancer patients with subsequent bladder/prostate over 6 months was generally improved relative to that of single lung cancer, which are similar to our previous report regarding survival of female lung cancer with subsequent breast cancer. Meanwhile, male lung cancer patients with prior urinary cancer experienced varied prognosis: survival of lung cancer with prior bladder cancer was similar to that of single lung cancer, which supported involvement of these patients into clinical trials. However, prognosis of lung cancer with prior prostate cancer was generally improved, which may complicate the results when these patients were involved into clinical trials. Further study is still required to confirm our results and clarify the mechanisms mediating survival advantage of patients with the two primary cancers.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of SEER.

References

Aguiló, R. et al. Multiple independent primary cancers do not adversely affect survival of the lung cancer patient. Eur. J. Cardio-thorac. Surgery Off. J. Eur. Assoc. Cardio-thorac. Surgery 34(5), 1075–1080 (2008).

Wu, Y. et al. Effect of prior cancer on survival outcomes for patients with advanced prostate cancer. BMC Urol. 21(1), 26 (2021).

Hoshimoto, S. et al. Outcomes in patients with pancreatic cancer as a secondary malignancy: A retrospective single-institution study. Langenbecks Arch. Surgery 404(8), 975–983 (2019).

Gray, E. et al. Chemotherapy effectiveness in trial-underrepresented groups with early breast cancer: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 16(12), e1003006 (2019).

Lv, F. et al. Survival analysis of patients with primary breast duct carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma: A population-based study from SEER. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 14790 (2021).

Cancer Stat Facts: Bladder Cancer. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (2021).

Cancer Stat Facts: Prostate Cancer. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (2021).

Donin, N. et al. Risk of second primary malignancies among cancer survivors in the United States, 1992 through 2008. Cancer 122(19), 3075–3086 (2016).

Afifi, A. M. et al. Causes of death after breast cancer diagnosis: A US population-based analysis. Cancer 126(7), 1559–1567 (2020).

Zhou, H. et al. Impact of prior cancer history on the overall survival of patients newly diagnosed with cancer: A pan-cancer analysis of the SEER database. Int. J. Cancer 143(7), 1569–1577 (2018).

Laccetti, A. L. et al. Effect of prior cancer on outcomes in advanced lung cancer: Implications for clinical trial eligibility and accrual. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 107(4), djv002 (2015).

Laccetti, A. L. et al. Prior cancer does not adversely affect survival in locally advanced lung cancer: A national SEER-medicare analysis. Lung Cancer 98, 106–113 (2016).

Pruitt, S. L. et al. Revisiting a longstanding clinical trial exclusion criterion: Impact of prior cancer in early-stage lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer 116(6), 717–725 (2017).

Herman, M. et al. The effect of prior cancer on non-small cell lung cancer trial eligibility. Cancer Med. 10(14), 4814–4822 (2021).

Cancer Clinical Trial Eligibility Criteria. Patients with Organ Dysfunction or Prior or Concurrent Malignancies (The Food and Drug Administration, 2020).

Gerber, D. E. et al. Impact of prior cancer on eligibility for lung cancer clinical trials. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 106(11), dju302 (2014).

Massard, G. et al. Lung cancer following previous extrapulmonary malignancy. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 18(5), 524–528 (2000).

Sankila, R. & Hakulinen, T. Survival of patients with colorectal carcinoma: effect of prior breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90(1), 63–65 (1998).

Fehringer, G. et al. Cross-cancer genome-wide analysis of lung, ovary, breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer reveals novel pleiotropic associations. Cancer Res. 76(17), 5103–5114 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DR. Z.: study design, results discussion and manuscript preparation. DR. L. and DR. C.: data extraction and analysis, manuscript preparation; DR. H.: data extraction, results discussion and language polishing; DR. J.: date analysis and results discussion. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Cheng, M., Hu, P. et al. Prognosis of male lung cancer patients with urinary cancer: a study from a national population-based analysis. Sci Rep 13, 283 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-27566-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-27566-8