Abstract

Recently, noble gas has become a hot spot within the medical field like respiratory organ cerebral anemia, acute urinary organ injury and transplantation. However, the shield performance in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury (CIRI) has not reached an accord. This study aims to evaluate existing evidence through meta-analysis to determine the effects of inert gases on the level of blood glucose, partial pressure of oxygen, and lactate levels in CIRI. We searched relevant articles within the following both Chinese and English databases: PubMed, Web of science, Embase, CNKI, Cochrane Library and Scopus. The search was conducted from the time of database establishment to the end of May 2023, and two researchers independently entered the data into Revman 5.3 and Stata 15.1. There were total 14 articles were enclosed within the search. The results showed that the amount of partial pressure of blood oxygen in the noble gas cluster was beyond that in the medicine gas cluster (P < 0.05), and the inert gas group had lower lactate acid and blood glucose levels than the medical gas group. The partial pressure of oxygen (SMD = 1.51, 95% CI 0.10 ~ 0.91 P = 0.04), the blood glucose level (SMD = − 0.59, 95% CI − 0.92 ~ − 0.27 P = 0.0004) and the lactic acid level (SMD = − 0.42, 95% CI − 0.80 ~ − 0.03 P = 0.03) (P < 0.05). These results are evaluated as medium-quality evidence. Inert gas can effectively regulate blood glucose level, partial pressure of oxygen and lactate level, and this regulatory function mainly plays a protective role in the small animal ischemia–reperfusion injury model. This finding provides an assessment and evidence of the effectiveness of inert gases for clinical practice, and provides the possibility for the application of noble gases in the treatment of CIRI. However, more operations are still needed before designing clinical trials, such as the analysis of the inhalation time, inhalation dose and efficacy of different inert gases, and the effective comparison of the effects in large-scale animal experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, the number of sudden death cases caused by cardiovascular diseases is increasing year by year, which is a growing concern1,2. Previous studies showed asystole was presently the leading reason behind death in patients with extra time3. At present, the current key to resuscitating cardiac arrest (CA) patients is the timely implementation of cardiac resuscitation (CPR) once CA occurs to make reperfusion in various organs of the patient during ischemia4. However, several studies have shown that after performing CPR on patients who experience cardiac arrest, most patients exhibit varying degrees of neurological deficits5, such as convulsions, coma, persistent vegetative state, and even death6, which is post-cardiac arrest syndrome (PCAS), this condition contains a poor prognosis and high mortality7. Tissue hypoperfusion and ischemia often occur in critically ill patients, and they are important factors contributing to multiple organ failure and perioperative mortality in patients. Therefore, ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI) is a significant problem, with high incidence and mortality rates associated with various diseases it causes. This process involves a chain reaction of events that includes the activation of apoptotic pathways, inflammatory response, release of oxygen radicals, brain cell swelling, Ca2+ overload, and accumulation of excitatory amino acids (EAA) etc.8,9. Although there is currently no effective treatment for IRI, a growing number of studies are exploring the use of inhaled drugs to reduce IRI.

There have been studies on the use of two inert gases, helium and xenon, for the treatment of IRI. Helium is occasionally used for ventilatory therapy in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and for improving cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury10,11. Xenon exhibits anesthetic properties under normobaric conditions and is known to be the fastest-acting and fastest-recovering among all known anesthetics. It also has highly desirable cardiovascular characteristics, making it very safe. Xenon also plays a certain role in brain protection during the middle and late stages of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion12,13. However, currently, there is no comprehensive review that summarizes and evaluates these studies. Therefore, this study aims to systematically review the literature to assess the current evidence on the use of inert gases for treating IRI and to explore the prospects and challenges of this treatment approach.

Result

Literature search results

A total of 2292 articles were searched. 1240 duplicate studies were initially excluded, 891 studies were excluded (388 articles unrelated to the theme; 201 reviews; 101 conference reports; 25 systematic evaluations) after reading the title, 501 studies were excluded after reading the full text (21 papers with lower quality risk scores; 201 articles that do not meet the inclusion criteria). Therefore 14 articles were eventually included in this study. The literature selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

General research features

This study included 14 relevant literatures published between 2003 and 2023. All interventions are based on inert gases. The measurement results include blood glucose levels, lactate acid levels, and partial pressure of oxygen. The basic characteristics of the included studies were listed in Table 1.

Evaluation of research quality

Research quality was scored from 3 to 6, and all included studies were published in peer-reviewed journals, 8 studies mentioned temperature control14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21: including room temperature or indoor water temperature; 9 studies used randomization14,15,16,17,19,20,21,22,23; 9 studies mentioned compliance with animal welfare regulations14,15,18,19,20,21,22,23,24; 11 studies stated that the use of anesthetics has no apparent neuroprotective properties14,15,16,17,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. 4 studies used animal models of diabetes, hypertension or geriatrics18,19,26,27. The quality assessment of the studies was shown in Table 2.

Effectiveness of the intervention

The blood glucose levels

Four existing studies reported that the levels of blood glucose showed statistically significant differences (P < 0.0001) between the intervention group (inert gas) and the control group (medical air) in animal models, the blood glucose level was significantly increased in the inert gas compared to medical air. Moreover, the level of heterogeneity among the 4 studies was relatively low (I2 = 17%, P = 0.31). Therefore, we used fixed effects model to analyze the data, as shown in Fig. 2 (SMD = − 0.59, 95% CI − 0.92 ~ − 0.27, P < 0.0001). The results of the fixed effect model obtained were SMD = 0.73, 95% CI 0.17 ~ 1.29 P = 0.01 after comprehensively removing a larger sample. This result showed there were no significant effects on the results when the model changed, indicating that the results of this meta-analysis were robust.

Lactic acid levels

We observed differences in lactic acid levels between the intervention group (inert gas) and the control group (medical air). The analysis showed heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.57) and used a fixed effect model (used a fixed-effects model) (Fig. 3). The effects confirmed that the level of lactic acid in the inert gas group was once decreased than that in the medical air group. The effects are proven in the determine (SMD = − 0.42, 95% CI − 0.80 ~ − 0.03, P = 0.03). After comprehensively putting off a giant sample, the consequences of the constant impact mannequin (SMD = − 0.49, 95% CI − 0.96 ~ − 0.01, p = 0.05) are obtained. The exchange of the mannequin has no tremendous effect on the results, indicating that the consequences of the meta-analysis were robust.

Partial pressure of blood oxygen

There were differences in blood oxygen partial pressure between the inert gas group and the medical gas group. The results are shown in the Fig. 4 (MD = 1.51, 95% CI 0.10 ~ 2.91, P = 0.04). Heterogeneity was shown (I2 = 0%, P = 0.57) and a fixed effect model was used. The consequences confirmed that the partial stress of blood oxygen in inert gas group was once greater than that in the medical air group. After comprehensively doing away with a giant sample, the outcomes of the constant impact mannequin (MD = 1.50, 95% CI 0.09 ~ 2.91, p = 0.04) are obtained. The alternative of the mannequin has no full-size effect on the results, indicating that the effects of the meta-analysis were robust.

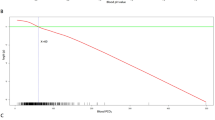

Publication bias

Results checked by funnel plot and Egger's test showed no publication bias, the blood glucose (p = 0.585), partial pressure of oxygen (p = 0.336) and lactic acid (p = 0.230).

Discussion

This study analyzed 14 published animal models of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury (CIRI), and compared the degree of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury (cerebral ischemia) and its blood glucose level, partial pressure of blood oxygen and lactate acid level in the animal models with inert gas inhalation and medical air inhalation. It is important to note that in animal models, the use of inert gas inhalation was found to be beneficial for controlling cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury (brain ischemia) in terms of the blood glucose level, blood oxygen partial pressure and lactate acid level.

As is well known, the human brain relies on aerobic glycolysis to meet its metabolic needs, and it itself does not have any energy reserves24. Studies have shown that in the absence of energy in brain tissue, the transmembrane transport of glucose may be the rate-limiting process of glucose utilization. The body can attempt to ensure the most basic energy demand by increasing glucose uptake rate, which is a protective response of cells28. The results of this study indicate that in the early stages of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury (cerebral ischemia) in animal models, the use of inert gas inhalation results in stable and relatively non-high levels of glucose control, which is more conducive to brain protection. This is consistent with the view of some researchers that elevated blood glucose concentrations on admission to hospital in patients with cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury are often associated with adverse outcomes in clinical practice, regardless of diabetes. At the same time, strict glycemic control in clinical practice has failed to produce any beneficial results29,30. After cerebral ischemia–reperfusion, hyperglycaemia is an independent risk factor for worsening prognosis, and the mechanism by exacerbates ischaemia/reperfusion injury may be directly related to elevated blood glucose, particularly neuroinflammation31. At the same time, preclinical studies in various animal I/R models and clinical studies to control elevated blood glucose have failed to produce neuroprotective effects, but have occasionally led to side effects32,33. Other studies have shown that an increase in glucose in the residual blood flow to the ischemic brain is beneficial for cell survival, as the reduced transport of glucose and oxygen during cerebral ischemia–reperfusion leads to significant depletion of adenosine 5 '- triphosphate (ATP) in the brain, which affects many downstream biological processes and leads to neuronal cell death34,35. In summary, blood glucose regulation is stable and maintained at a non-high level, which is more favorable for the recovery of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury.

In addition, the accumulation of lactic acid after cerebral ischemia leads to a decrease in the pH value of tissue, which can cause brain tissue damage, lipid peroxidation and free radical generation, eventually leading to irreversible cell damage. Nilsson et al. found that increased lactate levels are closely related to symptoms of cerebral ischemia, and high concentrations of lactate have a certain correlation with severe ischemia36. The lactate acid level in the brain during ischemia will not show a higher level when the glycogen reserve in the brain is very low, but during the period of enhanced anaerobic glycolysis, the lactate concentration will further increase. The production of brain lactate is mainly concentrated in the low perfusion period, accompanied by the increase of lactate, and irreversible damage to the structure of the cortical nerve cell membrane occurs. A study has reported that elevated glutamate induced by cerebral ischemia can lead to an increase in lactate production in astrocytes37. Persson et al. reported there was a threshold-type relationship between lactate concentration and glucose level38,39. Consistent with previous research findings, our study found the level of lactic acid was lower in the inert gas group compared to the control group at the early stage of CIRI, indicating the use of inert gas reduced the production of lactic acid, thus attenuating the occurrence of brain injury during ischemia–reperfusion.

Moreover, during periods of cerebral hypoperfusion, arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2) levels may be altered, which may affect the oxygen supply to the brain, thereby exacerbating the severity of brain injury. Elmer et al. confirmed that a threshold of 40 kpa for hyperoxia was an adverse outcome, but also suggested that moderate hyperoxia (PaO2 13.5–39.9 kPa) levels may have beneficial effects on the recovery of brain injury40. When cerebral ischemia causes low partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2), a large increase in PaCO2 levels may be associated with worsening cerebral edema, respiratory acidosis, and impaired right ventricular function, all of which may lead to a poor prognosis41,42,43. While, studies have shown that high levels of PaO2 in the early stage of reperfusion after cardiac arrest can exacerbate ischemia–reperfusion injury44. They showed poor neurological prognosis and increased nerve damage after hyperoxemia44, this finding has also been confirmed by clinical human studies45,46,47. But in retrospective and observational studies in human, severe hyperoxemia (PaO2 > 40 kpa) was associated with a poor prognosis after cardiac arrest48. In contrast, moderate-to-moderate hyperoxia in intensive care after resuscitation was associated with better long-term neurological recovery and improved organ function. Retrospective analysis of a large ICU showed that the lowest mortality rate was associated with a PaO2 of approximately 20 kPa49. Therefore, an appropriate increase in partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) can help the recovery of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury. Currently, there is limited high-quality data, and intervention studies are needed to determine the optimal oxygen concentration after cerebral ischemia and the potential association between oxygen therapy and prognosis.

Preclinical efficacy experiments are commonly cited to demonstrate the rationality of starting clinical trials. Our findings contribute to the literature on preclinical design and strengthen the exploratory study of the protective mechanism of inert gases in cerebral ischemia. Through this study, we determined that the induction of inert gases increased the animal's partial pressure of oxygen, proper blood glucose levels and decreased lactic acid level, which greatly reduced the degree of CIRI. Furthermore, this study can reduce unnecessary repeated experiments, facilitate deeper research in animal experiments, and may improve the success rate of future clinical trials.

However, the average quality score of the relevant studies during this paper is 4.38. Several studies don't describe their methods intimately, such as allocation concealment, blinded outcome assessment, hidden allocation etc. Additionally, there were several reasons that led to some biases: Firstly, different animal species, different concentrations, and different inhalation times were employed in various studies. Secondly, the animal models employed in most studies were healthy, while patients with cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury (cerebral ischemia) usually suffer from polygenic disease, cardiovascular disease, hyperlipoidaemia and different connected underlying diseases. Thirdly, our search strategy only included Chinese and English databases. Fourth, the number of included literatures is limited, and sub-group analysis was not conducted. Therefore, the interpretation of this result ought to use caution.

In addition, heterogeneity in meta-analyses was influenced by experimental conditions tested in various original studies and differences in experimental settings, and may vary considerably. For example, in the experimental design of individual studies, according to most of the current studies, the most effective time point for inert gas administration is still unknown. In particular, pretreatment may be ideal for predicting the onset of Ischemia–reperfusion in surgical management, including brain, heart, kidney, liver, and even transplantation, However, the onset of ischemia is most often sudden or unexpected. Therefore, the conclusions of our meta-analysis should be interpreted as a simple summary of the results of the individual literature, rather than as a reference to the size of the expected effect in a well-defined homogeneous environment. While most of the available evidence confirms the role of inert gases in animal models of cerebral ischemia, it remains unknown whether the doses of brain protection found in animal experiments can be applied universally to the human environment. Different species show different sensitivities to inert gases, which may also be organ-specific.

Conclusion

In summary, the results of this study indicate that the application of inert gases has a significant protective effect on experimental animals in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury (cerebral ischemia). Moreover, inert gases can alleviate ischemic brain injury by regulating blood glucose at a stable or non-elevated levels, increasing partial pressure of oxygen, and reducing lactate (salt) levels. However, the types of animals used and the methods of measuring results are all based on animals, which may have some deviation with future clinical trials. Therefore, consideration should be given to future clinical trial design and research. And inert gas will play a greater role in clinical applications in the future.

Methods

Since all the studies included in this study are published articles, there are no ethical issues to disclosure.

Retrieval strategy

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews. The retrieval database embraces English databases like PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and Chinese databases like CNKI. The retrieval time was from the establishment to May 31st, 2023. The search strategy was decided based on Pubmed's grid words combined with keywords from the necessary English and Chinese articles. English search terms include: (“cerebral anemia” or “cerebral schemia-reperfusion injury ”), (“inert gas” or “noble gas” or “helium ” or “xenon” or “neon”), (“Protective factor” or “Influencing factors ” or “Facilitator”) and (“randomized controlled trial” or “randomized” or “randomly” or “trial” or “groups”). The Chinese keywords include: (“cerebral anemia-reperfusion injury” or “cerebral ischemia, nerve injury” or “cerebral ischemia”), (“inert gas” or “rare gas” or “xenon” or “helium” or “neon” or “argon”), (“protective effect” or “influencing factor” or “promoting factor”) and (“randomized control” or “randomized grouping” or “randomizaton”).

After a literature search, we analyzed the titles and abstracts of the articles and excluded those that were not relevant to this meta-analysis. Next, we carefully read the full text of the remaining articles until all included articles were identified. In addition, to ensure the comprehensiveness of the search, we further searched the references of relevant reviews, meta-analyses or systematic reviews. All retrieved records are imported into Endnote X9 software for classification. After reviewing the titles and abstracts and reading the full text of the remaining studies, we selected studies that met the criteria for this meta-analysis. This process was completed independently by two researchers. In the case of different opinions, the decision was made after consultation with the third researcher.

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. It has been registered with the National Institute for Health Research in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42023457851).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion:(1) The study subjects include animal models and humans; (2) The intervention group was treated with an inert gas for inducing cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury, while the other group was treated with medical air for inducing cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury; (3) The research content includes the determination of blood glucose level, partial pressure of oxygen and lactate (salt) level.

Exclusion: (1) Observational studies, reviews, comments, letters and conferences, literature with incomplete research data; (2) Repeat; (3) Full text not available; (4) The data is incomplete or not suitable for meta-analysis; (5) Other types of interventions are used besides inert gases.

Data analysis

We extracted authors, years, countries, study design, sample size (experimental group/control group), participants, intervention, results etc. from the article. Then enter the data into Revman5.3 and STATA15.1. If I2 < 50%, P > 0.10, indicating low heterogeneity among included studies, a fixed-effects model was used. If I2 > 50%, P < 0.10, indicating that the included studies were highly heterogeneous, the results were summarized using a random-effects model. For continuous data, standardized mean difference (SMD) and mean weighted mean difference (MD) were used to calculate the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). When p < 0.05, the difference was statistically significant. Publication bias was assessed by visual funnel plots and quantitative computational Egger's test (STATA software).

Risk of bias assessment

This study was assessed according to the ten-item checklist of the CAMARADES checklist: (1) Peer-reviewed journals; (2) Body temperature control; (3) Animals are randomly assigned; (4) Blind model building; (5) Blinded result assessment; (6) Use of anesthetics with no apparent neuroprotective properties Use of anesthetics with no apparent neuroprotective properties; (7) Animal model (diabetes、old age or high blood pressure); (8) Calculation of sample size; (9) Statement of compliance with animal welfare regulations; (10) Possible conflict of interest.

The quality of each study was assessed on a scale of 0 to 10. Data were extracted independently by two assessors and the quality of each study was assessed. In case of any discrepancies, it shall be resolved through discussion with a third person.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the methods.

References

Benjamin, E. J. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 135, e146–e603 (2017).

Stecker, E. C. et al. Public health burden of sudden cardiac death in the United States. Circulation 7, 212–217 (2014).

Nolan, J. P. et al. Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A Scientific Statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation; the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Council on Stroke. Resuscitation 79, 350–379 (2008).

Hayashida, K. et al. Estimated cerebral oxyhemoglobin as a useful indicator of neuroprotection in patients with post-cardiac arrest syndrome: A prospective, multicenter observational study. Crit. Care 18, 500 (2014).

Yoshida, H. ER stress and diseases. FEBS J. 274, 630–658 (2007).

Laver, S., Farrow, C., Turner, D. & Nolan, J. Mode of death after admission to an intensive care unit following cardiac arrest. Intensive Care Med. 30, 2126–2128 (2004).

Kang, M. J. & Lee, T. R. Survival and neurologic outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients who were transferred after return of spontaneous circulation for integrated post-cardiac arrest syndrome care: The another feasibility of the cardiac arrest center. J. Korean Med. Sci. 29, 1301–1307 (2014).

Suliman, H. B. & Piantadosi, C. A. Mitochondrial quality control as a therapeutic target. Pharmacol. Rev. 68, 20–48 (2016).

Qian, J. et al. Post-resuscitation intestinal microcirculation: Its relationship with sublingual microcirculation and the severity of post-resuscitation syndrome. Resuscitation 85, 833–839 (2014).

Liu, Y. et al. Helium preconditioning attenuates hypoxia/ischemia-induced injury in the developing brain. Brain Res. 1376, 122–129 (2011).

David, H. N. et al. Post-ischemic helium provides neuroprotection in rats subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced ischemia by producing hypothermia. J. Cerebr. Blood Flow Metab. 29, 1159–1165 (2009).

Ma, D. et al. Xenon preconditioning reduces brain damage from neonatal asphyxia in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 26, 199–208 (2006).

Limatola, V. et al. Xenon preconditioning confers neuroprotection regardless of gender in a mouse model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neuroscience 165, 874–881 (2010).

Brücken, A. et al. Dose dependent neuroprotection of the noble gas argon after cardiac arrest in rats is not mediated by K(ATP)-channel opening. Resuscitation 85, 826–832 (2014).

Brücken, A. et al. Influence of argon on temperature modulation and neurological outcome in hypothermia treated rats following cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 117, 32–39 (2017).

Aehling, C. et al. Effects of combined helium pre/post-conditioning on the brain and heart in a rat resuscitation model. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 62, 63–74 (2018).

Chakkarapani, E. et al. Xenon enhances hypothermic neuroprotection in asphyxiated newborn pigs. Ann. Neurol. 68, 330–341 (2010).

David, H. N. et al. Neuroprotective effects of xenon: A therapeutic window of opportunity in rats subjected to transient cerebral ischemia. FASEB J. 22, 1275–1286 (2008).

David, H. N. et al. Ex vivo and in vivo neuroprotection induced by argon when given after an excitotoxic or ischemic insult. PLoS ONE 7, e30934 (2012).

Haelewyn, B. et al. Modulation by the noble gas helium of tissue plasminogen activator: Effects in a rat model of thromboembolic stroke. Crit. Care Med. 44, e383-389 (2016).

Ryang, Y. M. et al. Neuroprotective effects of argon in an in vivo model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Crit. Care Med. 39, 1448–1453 (2011).

Homi, H. M. et al. The neuroprotective effect of xenon administration during transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Anesthesiology 99, 876–881 (2003).

Schmidt, M., Marx, T., Glöggl, E., Reinelt, H. & Schirmer, U. Xenon attenuates cerebral damage after ischemia in pigs. Anesthesiology 102, 929–936 (2005).

Papasilekas, T. et al. A brief review of brain’s blood flow-metabolism coupling and pressure autoregulation. J. Neurol. Surg. Part A 82, 257–261 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Post-stroke treatment with argon attenuated brain injury, reduced brain inflammation and enhanced M2 microglia/macrophage polarization: A randomized controlled animal study. Crit. Care 23, 198 (2019).

Faulkner, S. et al. Xenon augmented hypothermia reduces early lactate/N-acetylaspartate and cell death in perinatal asphyxia. Ann. Neurol. 70, 133–150 (2011).

Grüne, F. et al. Argon does not affect cerebral circulation or metabolism in male humans. PLoS ONE 12, e0171962 (2017).

Devaskar, S. U. et al. Effect of development and hypoxic-ischemia upon rabbit brain glucose transporter expression. Brain Res. 823, 113–128 (1999).

Sharma, D. & Smith, M. The intensive care management of acute ischaemic stroke. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 28, 157–165 (2022).

Johnston, K. C. et al. Intensive vs standard treatment of hyperglycemia and functional outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke: The SHINE randomized clinical trial. Jama 322, 326–335 (2019).

Alloubani, A., Saleh, A. & Abdelhafiz, I. Hypertension and diabetes mellitus as a predictive risk factors for stroke. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 12, 577–584 (2018).

Wass, C. T. & Lanier, W. L. Glucose modulation of ischemic brain injury: Review and clinical recommendations. Mayo Clin. Proc. 71, 801–812 (1996).

MacDougall, N. J. & Muir, K. W. Hyperglycaemia and infarct size in animal models of middle cerebral artery occlusion: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cerebr. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 807–818 (2011).

Robbins, N. M. & Swanson, R. A. Opposing effects of glucose on stroke and reperfusion injury: Acidosis, oxidative stress, and energy metabolism. Stroke 45, 1881–1886 (2014).

Barthels, D. & Das, H. Current advances in ischemic stroke research and therapies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1866, 165260 (2020).

Nilsson, O. G., Brandt, L., Ungerstedt, U. & Säveland, H. Bedside detection of brain ischemia using intracerebral microdialysis: Subarachnoid hemorrhage and delayed ischemic deterioration. Neurosurgery 45, 1176–1184 (1999) (discussion 1184-1175).

Meldrum, B. S. Excitatory amino acid receptors and their role in epilepsy and cerebral ischemia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 757, 492–505 (1995).

Persson, L. et al. Neurochemical monitoring using intracerebral microdialysis in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurosurge. 84, 606–616 (1996).

Alessandri, B. et al. Application of glutamate in the cortex of rats: A microdialysis study. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 67, 6–12 (1996).

Elmer, J. et al. The association between hyperoxia and patient outcomes after cardiac arrest: Analysis of a high-resolution database. Intensive Care Med. 41, 49–57 (2015).

Ganga, H. V. et al. The impact of severe acidemia on neurologic outcome of cardiac arrest survivors undergoing therapeutic hypothermia. Resuscitation 84, 1723–1727 (2013).

Tiruvoipati, R. et al. Association of hypercapnia and hypercapnic acidosis with clinical outcomes in mechanically ventilated patients with cerebral injury. JAMA Neurol. 75, 818–826 (2018).

Mekontso Dessap, A. et al. Impact of acute hypercapnia and augmented positive end-expiratory pressure on right ventricle function in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 35, 1850–1858 (2009).

Pilcher, J. et al. The effect of hyperoxia following cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis of animal trials. Resuscitation 83, 417–422 (2012).

Kilgannon, J. H. et al. Association between arterial hyperoxia following resuscitation from cardiac arrest and in-hospital mortality. Jama 303, 2165–2171 (2010).

Kilgannon, J. H. et al. Relationship between supranormal oxygen tension and outcome after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Circulation 123, 2717–2722 (2011).

Janz, D. R., Hollenbeck, R. D., Pollock, J. S., McPherson, J. A. & Rice, T. W. Hyperoxia is associated with increased mortality in patients treated with mild therapeutic hypothermia after sudden cardiac arrest. Crit. Care Med. 40, 3135–3139 (2012).

Roberts, B. W. et al. Association between early hyperoxia exposure after resuscitation from cardiac arrest and neurological disability: Prospective multicenter protocol-directed cohort study. Circulation 137, 2114–2124 (2018).

Vaahersalo, J. et al. Arterial blood gas tensions after resuscitation from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Associations with long-term neurologic outcome. Crit. Care Med. 42, 1463–1470 (2014).

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82072127).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.W., H. Y. and J. X. conceived and designed the research; D.W., D. Z. and H.Y. performed the research and acquired the data; D.W., D .Z., H.Y. and B.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, D., Zhang, D., Yin, H. et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of inert gases on cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury. Sci Rep 13, 16896 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43859-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43859-4