Abstract

This paper investigates the intricate energy distribution patterns emerging at an orthotropic piezothermoelastic half-space interface by considering the influence of a higher-order three-phase lags heat conduction law, accompanied by memory-dependent derivatives (referred to as HPS) within the underlying thermoelastic half-space (referred to as TS). This study explores the amplitude and energy ratios of reflected and transmitted waves. These waves span various incident types, including longitudinal, thermal, and transversal, as they propagate through the TS and interact at the interface. Upon encountering the interface, an intriguing dynamic unfolds: three waves experience reflection within the TS medium, while four waves undergo transmission into the HPS medium. A graphical representation effectively illustrates the impact of higher-order time differential parameters and memory to offer comprehensive insights. This visual representation reveals the nuanced fluctuations of energy ratios with the incidence angle. The model astutely captures diverse scenarios, showcasing its ability to interpret complex interface dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many disciplines, including geophysics, earth-quake engineering, and seismology, have intensely interested in studying wave reflection and refraction phenomena. Studies of these phenomena are crucial for revealing the interior makeup of the Earth’s structure. They are significant when considering theoretical research and real-world applications in industries like mining and acoustics.

Fourier’s law of heat conduction provides a framework for the classical theory of thermoelasticity (CTE), developed by Duhamel. Fourier’s law produces the famous heat equation as the partial differential equation regulating heat transfer when coupled with the energy conservation law. There are two shortcomings in the CTE: first, the mechanical state of an elastic body does not affect the temperature, and second, the parabolic heat equation predicts an infinite propagation speed of heat. Biot1 proposed the model of coupled thermoelasticity, which stated that temperature changed independent of elastic variations and removed the first paradox of CTE. But the diffusion-type of heat conduction equation makes it difficult for the CTE and the Biot theory of thermoelasticity to describe the thermal signal velocity mechanism.

In 1967, to overcome this difficulty, Lord and Shulman (L–S)2 developed the generalized thermoelastic theory by incorporating one relaxation time into Fourier’s heat transfer law. Green and Lindsay3 developed the second generalized theory of thermoelasticity with two relaxation time parameters and included the temperature rate-dependent term in the heat equation. For the homogenous isotropic material, the three new thermoelastic models depending on the energy dissipation and thermal signal, were developed by Green and Naghdi4,5,6 and labeled as GN-I, GN-II, and GN-III. The linearized form of the GN-I model is the same as the CTE and displays the heat conduction paradox. The finite heat conduction speed without energy dissipation predicted by the GN-II model makes it the most controversial of the three. The GN-III model includes the preceding two models as exceptional cases. In GN-III model, a second sound may arise, but only when there is no dissipation, i.e., when the hyperbolic heat equation.

Tzou7 proposed the dual-phase-lag (DPL) heat conduction model by introducing two phase lag times \(\tau_{q}\) (for heat flow) and \(\tau_{T}\) (for temperature gradient) in the heat conduction equation. Microscopically, phonon-electron interaction in metallic films and phonon scattering in dielectric films, insulators, and semiconductors control heat transfer. Classical theories made from the macroscopic point of view, like heat diffusion based on Fourier’s law, are unlikely to be helpful at the microscale since they depict the macroscopic average behavior of numerous grains. Finite periods, from femtoseconds to seconds or even longer, are needed to complete the microstructural interactions. The lagged response describes the temperature gradient and the heat flow vector, which appear at various points in the heat transfer process. Roy Choudhuri8 extended the DPL model and presented the three-phase-lag (TPL) model by introducing the new phase lag time \(\tau_{v}\) (for thermal displacement gradient).

In 2011, Wang and Li9 discovered the novel concept of memory-dependent derivatives (MDD) as a substitution of fractional order derivative, in which, using kernel function, the fractional derivative developed by Caputo and Mainardi10 was transformed into an integral form of derivative, and it can be written mathematically as

Here, the kernel function \(\kappa (t - \zeta )\) and the time-delay parameter \(\tau > 0\) can be chosen freely depending on the nature of the problem. From a physical perspective11, we usually assume that \(0 < \kappa (t - \zeta ) \le 1\) and \(\tau\) should be less than the upper limit set by the kernel function to make sure that the solution is unique and exists such that

Also, Wang and Li12,13 proved that this concept is preferable to fractional calculus to display the instantaneous rate of change depending on the past state (memory effect). So many examples, like weather population models, forecasts, etc., need data from the recent past. This is only possible with the concept of MDD because fractional derivatives fail if the lower terminal value is much less than the upper terminal value in the definition of fractional order derivatives.

In the last few decades, piezo thermoelectric materials have gained interest in energy harvesting structures, actuators, transducers, dynamic sensing, surface acoustic wave, intelligent networks, mechanical systems, etc. Both experimental and theoretical studies on wave propagation in piezothermoelastic materials are active research subjects for researchers, scientists, and engineers. Mindlin14 was the first person who developed the piezothermoelectricity theory and its governing equation. Later, Nowacki15 and Chandrasekharaiah16 extended the physical law of piezothermoelectricity. Recently, Gupta and his team17,18,19,20,21,22,23 studied the various reflection and deformation problems at the interface of piezothermoelastic medium under different piezothermoelasticity theories. Several researchers, Barak et al.24 and Kumar et al.25,26,27, verified the energy balance law of incident, reflected and transmitted waves at the interface of various media. Li and his research team28,29,30,31 delved into the diverse challenges surrounding the thermo-electromechanical behavior of intricate piezoelectric smart nanocomposite structures by employing the size-dependent piezoelectric thermoelasticity theory and using the Laplace transformation technique.

To better understand the high-order consequences of thermal lagging, Chiriţă32 studied resonance phenomena under high-frequency excitations about micro or nanoscale heat transport models. This issue is significant when the model being considered has to account for interactions between various energy carriers as well as the impacts of the microstructural interactions that play a role in the quick and transitory transport of heat transient. Recently, Abouelregal and his team33,34,35,36 worked on several problems about the higher-order time differential of heat conduction equation by expanding Fourier’s law with Taylor’s series expansion. They successfully developed the idea of higher order time differential on various generalized thermoelastic theories such as L-S, GN-II, GN-III, DPL, and TPL under the presence and absence of MDD.

In this current manuscript, the energy ratios of various reflected/transmitted waves for incidence P, T, or SV at the interface \(x_{3} = 0\) of orthotropic piezothermoelastic half-space in the context of a triple-phase lag heat conduction law with higher order MDD underlying a thermoelastic half-space are investigated. The impact of higher-order MDD on the various energy ratios is analyzed and depicted graphically.

Basic equations

The constitutive relations for a homogenous, anisotropic piezothermoelastic solid under three-phase lag heat transfer law with higher-order MDD in the absence of free charge density, body forces, and shear forces are given by Abouelregal et al.36 and Barak and Gupta37, as

the higher orders \(p,\,l,\,n\,\, \in \,{\rm N}\) and \(i,\,j,\,r,\,o = 1,2,3\). Chiriţă et al.38 show that \(n \ge 5\) or \(p \ge 5\) leads to an unstable system, and therefore they cannot accurately describe an actual situation. Tzou39 presented a fascinating concept concerning this heat equation when \(n = p\) or when \(n = p - 1\) connecting the progressive exchange between the diffusive and wave behaviors.

The governing equations for a thermoelastic solid without energy dissipation and body forces are given by Green and Naghdi6 as:

Limiting cases

This work shows that the higher-order MDD piezothermoelastic proposed model is an extension of numerous generalized models, with or without the memory effect. The three-phase lag heat transfer law with higher order memory-dependent derivative Eq. (7) in the limiting case by setting.

Case 1: \(\tau_{q} = \tau_{T} = \tau_{v} = 0\), and \(K_{ij}^{*} = 0\) corresponds to Biot1 model.

Case 2: \(n = 1\), \(\tau_{q} > 0\), \(\tau_{v} = \tau_{T} = 0\), \(K_{ij}^{*} = 0\), \(\kappa \left( {t - \zeta } \right) = 1\), and \(D_{\tau } \to \frac{\partial }{\partial t}\) corresponds to Lord and Shulman’s2 model.

Case 3: \(n \ge 1\), \(\tau_{q} > 0\), \(\tau_{v} = \tau_{T} = 0\), and \(K_{ij}^{*} = 0\), transforms into the higher order MDD heat equation with one delay time \(\tau_{q}\) developed by Abouelregal et al.35.

Case 4: \(\tau_{q} = \tau_{T} = \tau_{v} = 0\), \(K_{ij} = 0\), \(\kappa \left( {t - \zeta } \right) = 1\), and \(D_{\tau } \to \frac{\partial }{\partial t}\) corresponds to Green and Naghdi type-II model.

Case 5: \(\tau_{q} = \tau_{T} = \tau_{v} = 0\), \(\kappa \left( {t - \zeta } \right) = 1\), and \(D_{\tau } \to \frac{\partial }{\partial t}\) corresponds to Green and Naghdi type-III model.

Case 6: \(p = 1\), \(n = 2\), \(K_{ij}^{*} = \tau_{v} = 0\), \(\kappa \left( {t - \zeta } \right) = 1\), and \(D_{\tau } \to \frac{\partial }{\partial t}\) corresponds to Tzou7 model.

Case 7: \(p = l = 1\), \(n = 2\), \(K_{ij}^{*} = \tau_{v} = 0\) corresponds to Ezzat et al.40 model.

Case 8: \(n,\,p \ge 1\), \(K_{ij}^{*} = \tau_{v} = 0\) transforms into the dual phase-lags heat conduction equation with higher order MDD developed by Abouelregal41.

Case 9: \(p = l = 1\), \(n = 2\), \(\kappa \left( {t - \zeta } \right) = 1\), and \(D_{\tau } \to \frac{\partial }{\partial t}\) corresponds to Roy Choudhuri8 model.

Case 10: \(p = l = 1\), and \(n = 2\), corresponds to Ghosh et al.42 model.

Case 11: \(n,p,l \ge 1\), \(\kappa \left( {t - \zeta } \right) = 1\), and \(D_{\tau } \to \frac{\partial }{\partial t}\) change into the higher-order time derivative three-phase lag heat equation without MDD proposed by Abouelregal33.

Nomenclature

\(c_{ijro} =\) elastic stiffness tensor | \(\beta_{ij} =\) thermal moduli tensors |

\(\eta_{ijr} ,\,\varepsilon_{ij} =\) piezothermal moduli tensors | \(E_{i} =\) electric field density |

\(\rho =\) density | \(D_{i} =\) electric displacement |

\(e_{ij} =\) component of strain | \(\lambda ,\,\mu =\) Lame’s constant |

\(\omega \,\,\, =\) circular frequency | \(C_{E} =\) specific heat at constant strain |

\(K_{ij} =\) components of thermal conductivity | \(K_{ij}^{*} =\) heat conduction tensor |

\(\tau_{q} =\) phase lag of heat flux | \(K_{e}^{*} =\) material constant |

\(\tau_{v} =\) phase lag of thermal disp. gradient | \(p_{i} =\) pyroelectric constants |

\(\tau_{T} =\) phase lag of the temperature gradient | \(\phi =\) electrical potential |

\(\sigma_{ij} =\) components of the stress | \(T =\) thermal temperature |

\(T_{0} =\) reference temperature |

for clarity, engineering notations are employed, and the terms partial derivative with respect to time or the corresponding Cartesian coordinate are denoted by a superimposed dot “.” or a subscript followed by a comma “,”, respectively. A superscript “e” denotes thermoelastic half-space parameters.

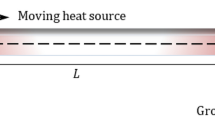

Formulation of the problem

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the orthotropic piezothermoelastic half-space under the reference of a triple-phase lag theory of higher order memory-dependent derivatives (HPS) (\(x_{3} > 0\)) underlying a thermoelastic half-space (TS) (\(x_{3} < 0\)) are welded together. The thermoelastic plane wave propagates in the \(x_{1} x_{3} -\) plane, and the displacement vector for HPS and TS is represented by \(\vec{u} = (u_{1} ,0,u_{3} )\) and \(\vec{u}^{e} = (u_{1}^{e} ,0,u_{3}^{e} )\) respectively.

Following Slaughter43, the governing equations for two-dimensional HPS medium are determined from Eqs. (3)–(8) as

where \(K_{ij} = K_{i} \delta_{ij}\), \(K_{ij} = K_{i}^{*} \delta_{ij}\), \(\beta_{ij} = \beta_{i} \delta_{ij} ,\) and \(i\) is not summed.

For convenience, the dimensionless quantities are taken as

Using the Eq. (16) in the set of Eqs. (10)–(11) and (12)–(15) with the removal of primes (′) takes the following form

where \(d_{11} = \frac{{c_{55} }}{{c_{11} }}\), \(d_{12} = \frac{{c_{13} + c_{55} }}{{c_{11} }}\), \(d_{13} = \frac{{\eta_{31} + \eta_{15} }}{{c_{11} \eta_{31} }}\beta_{1} T_{0}\), \(d_{21} = \frac{{c_{55} }}{{c_{55} + c_{13} }}\), \(d_{22} = \frac{{c_{33} }}{{c_{55} + c_{13} }}\) \(d_{23} = \frac{{c_{11} }}{{c_{55} + c_{13} }}\), \(d_{24} = \frac{{\eta_{15} \beta_{1} T_{0} }}{{\eta_{31} (c_{55} + c_{13} )}}\), \(d_{25} = \frac{{\eta_{33} \beta_{1} T_{0} }}{{\eta_{31} (c_{55} + c_{13} )}}\), \(d_{26} = \frac{{c_{11} \beta_{3} }}{{(c_{55} + c_{13} )\beta_{1} }}\), \(d_{31} = \frac{{K_{1}^{*} \rho }}{{T_{0} \beta_{1}^{2} }}\) \(d_{32} = \frac{{K_{3}^{*} \rho }}{{T_{0} \beta_{1}^{2} }}\), \(d_{33} = \frac{{K_{1} \omega_{1} \rho }}{{T_{0} \beta_{1}^{2} }}\), \(d_{34} = \frac{{K_{3} \omega_{1} \rho }}{{T_{0} \beta_{1}^{2} }}\), \(d_{35} = \frac{{\beta_{3} }}{{\beta_{1} }}\), \(d_{36} = \frac{{p_{3} T_{0} }}{{\eta_{31} }}\), \(d_{37} = \frac{{c_{11} \rho C_{E} }}{{T_{0} \beta_{1}^{2} }}\) \(d_{41} = \frac{{\eta_{15} }}{{(\eta_{15} + \eta_{31} )}}\), \(d_{42} = \frac{{\eta_{33} }}{{(\eta_{15} + \eta_{31} )}}\), \(d_{43} = \frac{{\varepsilon_{11} \beta_{1} T_{0} }}{{\eta_{31} (\eta_{15} + \eta_{31} )}}\), \(d_{44} = \frac{{\varepsilon_{33} \beta_{1} T_{0} }}{{\eta_{31} (\eta_{15} + \eta_{31} )}}\), \(\alpha_{2}^{e} = \sqrt {\frac{{\mu^{e} }}{{\rho^{e} }}}\)\(d_{45} = \frac{{c_{11} \tau_{3} }}{{\beta_{1} (\eta_{15} + \eta_{31} )}}\), \(d_{51} = \frac{{K_{e}^{*} \rho }}{{\beta_{1} \beta^{e} T_{0}^{e} }}\), \(d_{52} = \frac{{\rho^{e} \rho C_{E}^{e} c_{1}^{2} }}{{\beta_{1} \beta^{e} T_{0}^{e} }}\), \(\alpha_{1}^{e} = \sqrt {\frac{{\lambda^{e} + 2\mu^{e} }}{{\rho^{e} }}}\), \(\gamma = \frac{{\rho \beta^{e} }}{{\rho^{e} \beta_{1} }}\).

Method (wave propagation analysis)

Taking plane wave form solution for HPS medium as

where, \(H,\,M,\,N,\,U\) are the amplitude vectors, \(q\) and \(c\) are the slowness parameter, and the apparent phase velocity, respectively.

Inserting Eq. (24) in a set of Eqs. (17)–(20) yields a homogenous system

where,

\(l_{11} = c - c^{3}\), \(l_{12} = d_{11} c^{3}\), \(l_{13} = d_{12} c^{2}\), \(l_{14} = d_{13} c^{2}\), \(l_{15} = \frac{{\iota c^{2} }}{\omega }\), \(l_{21} = d_{21} - d_{23} c^{2}\), \(l_{22} = d_{22} c^{2}\), \(l_{23} = d_{25} c^{2}\), \(l_{24} = \frac{{\iota d_{26} \,c^{2} }}{\omega }\), \(l_{31} = d_{25} c^{2}\), \(l_{32} = d_{36} c^{2}\), \(l_{33} = \frac{{A_{1} d_{31} }}{{\iota \omega^{2} }} + A_{2} d_{33} - \frac{{d_{37} c^{2} }}{\iota \omega }\), \(l_{34} = \left( {A_{2} d_{34} - \frac{{\iota A_{1} d_{32} }}{\omega }} \right)c^{2}\), \(l_{41} = d_{42} c^{2}\), \(l_{42} = d_{44} c^{2}\), \(l_{43} = \frac{{\iota c^{2} d_{45} }}{\omega }\), \(A_{1} = \frac{{1 + \Gamma_{1} }}{{1 + \Gamma_{2} }},\) \(A_{2} = \frac{{1 + \Gamma_{3} }}{{1 + \Gamma_{2} }}\), \(\Gamma_{1} = \sum\limits_{m = 1}^{p} {\frac{{\tau_{T}^{m} }}{m!}b^{m - 1} \Gamma \left( {\tau_{T} ,b} \right)}\), \(\Gamma_{2} = \sum\limits_{m = 1}^{n} {\frac{{\tau_{q}^{m} }}{m!}b^{m - 1} \Gamma \left( {\tau_{q} ,b} \right)}\), \(\Gamma_{3} = \sum\limits_{m = 1}^{l} {\frac{{\tau_{v}^{m} }}{m!}b^{m - 1} \Gamma \left( {\tau_{v} ,b} \right)}\), \(b = \iota \omega\)

The coefficient matrix’s \(\Omega\) determinant must be zero for the non-trivial solution, leading to a characteristic equation.

When Eq. (27) is solved using the MATLAB software, the roots are found to be organized in magnitude-wise decreasing order and are denoted as follows for convenience: \(q_{i} \,\,\left( {i = 1 - 4} \right)\) represents the roots of this equation with positive imaginary parts and \(q_{i} \,\,\left( {i = 5 - 8} \right)\) represents those with negative imaginary parts. The eigenvalue \(q_{4}\) corresponds to the component of the electric potential \(\,(\,eP\,)\) mode of wave propagation and \(q_{i} \,\,\left( {i = 1 - 3} \right)\) corresponds to the quasi \(P\,\,(\,qP\,)\), quasi \(T\,\,(\,qT\,)\), and quasi \(S\,\,(\,qS\,)\) propagating modes, respectively. The expression \(G_{1i} \,\,\left( {i = 1 - 5} \right)\) is provided in the Appendix.

The eigenvectors \(H_{i}\), \(M_{i}\), \(N_{i}\), and \(U_{i}\) corresponding to each \(q_{i} \,\,\left( {i = 1 - 8} \right)\) can be written as

where

and \(cf\,\left( {\Omega_{ij} } \right)_{{q_{i} }}\) denote the cofactor \(G_{ij}\) corresponding to the eigenvalue \(q_{i}\). The corresponding amplitudes \(\left( {H_{i} ,\,M_{i} ,\,\,N_{i} {\text{ and}}\,\,U_{i} } \right)\) decrease when the thermoelastic plane waves go through the HPS medium, depending on the frequency of these waves.

Following Achenbach44, the displacement components of the TS medium can be expressed in terms of the potential function \(\phi^{e}\) and \(\psi^{e}\) by the relation

Using Eq. (30) in Eqs. (21)–(23), we get

where, \(\alpha_{1}^{*} = \frac{{\alpha_{1}^{e} }}{{c_{1} }}\), \(\alpha_{2}^{*} = \frac{{\alpha_{2}^{e} }}{{c_{1} }}\), \(a_{1}^{2} = \frac{{K_{c}^{*} }}{{\rho^{e} c_{1}^{2} C^{e} }}\), \(a_{2}^{2} = \frac{{\beta^{e} \beta_{1} T_{0}^{e} }}{{\rho \rho^{e} c_{1}^{2} C_{E}^{e} }}\).

For thermoelastic plane harmonic wave propagating in TS medium establishing an angle \(\theta_{0}\) with the \(x_{3} -\) axis (see Fig. 1), we can take

where \(k( = {\omega \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {\omega c}} \right. \kern-0pt} c})\) is the complex wavenumber, \(A_{{\phi^{e} }}\), \(A_{{T^{e} }}\), \(A_{{\psi^{e} }}\) are the wave amplitudes constants.

Using Eq. (34) in Eqs. (31)–(33), we get

where \(S_{1} = a_{1}^{2} + \alpha_{1}^{*2} + a_{2}^{2} \gamma\), \(S_{2} = \alpha_{1}^{*2} a_{1}^{2} .\)

Here \(r_{{e_{1} }}^{2}\), \(r_{{e_{2} }}^{2}\) corresponds to positive and negative signs, respectively. These roots indicate that two coupled longitudinal waves exist, namely, an elastic wave (P-wave) and a thermal wave (T-wave). \(r_{{e_{3} }}^{2}\) corresponds to transversal SV- wave.

Refraction and reflection coefficients

Amplitude ratios

Assuming that train of a thermoelastic plane wave (P or SV or T) striking at the interface via the TS medium form an angle \(\theta_{0}\) with the \(x_{3} -\) axis, causing three waves to be reflected in the TS medium and four waves to be transmitted in the HPS medium. The expression for the stress, electric displacement, mechanical displacements, electric potential, and temperature assumed in an HPS medium becomes

Boundary conditions

The possible boundary conditions, i.e., equality of distribution of normal stress, tangential stress, tangential displacement, and normal displacement, along with the isothermal, insulated boundaries, and vanishing of electric displacements across an interface, \(x_{3} = 0\) are as follows:

The full structures of the wave field made up of the incident and reflected wave in the TS medium meet the boundary conditions, are

where \(\zeta_{j} = \frac{{\omega^{2} }}{{r_{{e_{j} }}^{2} \gamma }}\left( {r_{{e_{j} }}^{2} - \alpha_{1}^{*2} } \right)\), \(j = 1,\,2\) and \(A_{0}^{e}\), \(B_{0}^{e}\), \(D_{0}^{e}\) (\(A_{1}^{e}\), \(B_{1}^{e}\), \(D_{1}^{e}\)) represent the coefficients of amplitudes of the incident (reflected) P-, T-, and SV- waves, respectively and

\(B_{0}^{e} ,\,D_{0}^{e} = 0\), for incidence of P-wave.

\(A_{0}^{e} ,\,D_{0}^{e} = 0\), for incidence of T-wave.

\(A_{0}^{e} ,\,B_{0}^{e} = 0\), for incidence of SV-wave.

Snell’s law is given as

where,

Using the set of Eqs. (36)–(43), we obtain a system of non-homogenous equations that may be expressed as

where

\(\Delta_{1i} = - \frac{{c_{13} }}{{\beta_{1} T_{0} c}} - \left( {\frac{{c_{33} W_{i} }}{{\beta_{1} T_{0} }} + \frac{{\eta_{33} }}{{\eta_{31} }}\Phi_{i} } \right)q_{i} - \frac{{c_{11} \beta_{3} }}{{\iota \omega \beta_{1}^{2} T_{0} }}\Theta_{i}\), \(\Delta_{2i} = - \frac{{c_{55} W_{i} }}{{\beta_{1} T_{0} c}} - \frac{{c_{55} q_{i} }}{{\beta_{1} T_{0} }} - \frac{{\eta_{15} \Phi_{i} }}{{c\eta_{31} }}\), \(\Delta_{3i} = 1\), \(\Delta_{4i} = W_{i}\), \(\Delta_{5i} = \Theta_{i}\), \(\Delta_{6i} = - \left[ {K_{3}^{*} \left( {1 + \tau_{v} \Gamma \left( {\tau ,b} \right)} \right) + K_{3} \left( {1 + \tau_{T} \Gamma \left( {\tau ,b} \right)} \right)\iota \omega \,\omega_{1} } \right]\Theta_{i} q_{i}\)

\(\Delta_{15} = \frac{{C_{T} \zeta_{1} + k_{1}^{2} \rho^{e} \left( {\alpha_{1}^{e2} - 2\alpha_{2}^{e2} \sin^{2} \theta_{1} } \right)}}{{\iota \omega \beta_{1} T_{0} }}\), \(\Delta_{16} = \frac{{C_{T} \zeta_{2} + k_{2}^{2} \rho^{e} \left( {\alpha_{1}^{e2} - 2\alpha_{2}^{e2} \sin^{2} \theta_{2} } \right)}}{{\iota \omega \beta_{1} T_{0} }}\), \(C_{T} = \frac{{c_{11} \beta^{e} }}{{\beta_{1} }}\).

\(\Delta_{17} = - \frac{{k_{3}^{2} \rho^{e} \alpha_{1}^{e2} \sin 2\theta_{3} }}{{\iota \omega \beta_{1} T_{0} }}\), \(\Delta_{25} = - \frac{{k_{1}^{2} \alpha_{1}^{e2} \rho^{e} \sin 2\theta_{1} }}{{\iota \omega \beta_{1} T_{0} }}\), \(\Delta_{26} = - \frac{{k_{2}^{2} \alpha_{2}^{e2} \rho^{e} \sin 2\theta_{2} }}{{\iota \omega \beta_{1} T_{0} }}\), \(\Delta_{27} = - \frac{{k_{3}^{2} \alpha_{2}^{e2} \rho^{e} \cos 2\theta_{3} }}{{\iota \omega \beta_{1} T_{0} }}\), \(\Delta_{35} = \iota k_{1} \sin \theta_{1}\), \(\Delta_{36} = \iota k_{2} \sin \theta_{2}\), \(\Delta_{37} = \iota k_{3} \cos \theta_{3}\), \(\Delta_{45} = - \iota k_{1} \cos \theta_{1}\),

\(\Delta_{46} = - \iota k_{2} \cos \theta_{2}\), \(\Delta_{47} = \iota k_{3} \sin \theta_{3}\), \(\Delta_{55} = - \zeta_{1}\), \(\Delta_{56} = - \zeta_{2}\), \(\Delta_{65} = \frac{{ - \zeta_{1} k_{1} K_{e}^{*} \cos \theta_{1} }}{\omega }\)\(\Delta_{66} = \frac{{ - \zeta_{2} k_{2} \cos \theta_{2} K_{e}^{*} }}{\omega }\), \(X_{i} = \frac{{H_{i} }}{{A^{*} }}\,\,\left( {i = 1 - 4} \right)\,,\) \(X_{5} = \frac{{A_{1}^{e} }}{{A^{*} }}\), \(X_{6} = \frac{{B_{1}^{e} }}{{A^{*} }}\), \(X_{7} = \frac{{D_{1}^{e} }}{{A^{*} }}\).

-

For incidence P wave: \(A^{*} = A_{0}^{e}\), \(Q_{1} = - \Delta_{15}\), \(Q_{2} = \Delta_{25}\), \(Q_{3} = - \Delta_{35}\), \(Q_{4} = \Delta_{45}\), \(Q_{5} = - \Delta_{55}\), \(Q_{6} = \Delta_{65}\).

-

For incidence T wave: \(A^{*} = B_{0}^{e}\), \(Q_{1} = - \Delta_{16}\), \(Q_{2} = \Delta_{26}\), \(Q_{3} = - \Delta_{36}\), \(Q_{4} = \Delta_{46}\), \(Q_{5} = - \Delta_{56}\), \(Q_{6} = \Delta_{66}\).

-

For incidence SV wave: \(A^{*} = D_{0}^{e}\), \(Q_{1} = \Delta_{17}\), \(Q_{2} = - \Delta_{27}\), \(Q_{3} = \Delta_{37}\), \(Q_{4} = - \Delta_{47}\), \(Q_{5} = 0\), \(Q_{6} = 0\).

Energy ratios

The average energy flux of the incident, refracted, and reflected waves could be used to figure out the energy distribution between refracted and reflected waves at the interface \(x_{3} = 0\), across a unit area of the surface element. According to Kumar and Sharma45, the normal acoustic flux in an HPS material is represented by as follows

and for the incident and reflected waves for the elastic phase are

The average energy fluxes of the incident waves are as follows

The average energy fluxes of the reflected waves are as follows

The average energy fluxes of the refracted waves are as follows

The energy ratios of the reflected and refracted waves are defined as.

(i) for incident \(P\) wave

(ii) for incident \(T\) wave

(iii) for incident \(SV\) wave

The interaction energy ratios (interaction between different fields and displacement corresponding to refracted waves) are.

\(E_{st} = \frac{{\left\langle {P_{st} } \right\rangle }}{{\left\langle {P_{IP}^{e} } \right\rangle }}\) for an incident of \(P\) wave, \(E_{st} = \frac{{\left\langle {P_{st} } \right\rangle }}{{\left\langle {P_{IT}^{e} } \right\rangle }}\) for an incident of \(T\) wave, and \(E_{st} = \frac{{\left\langle {P_{st} } \right\rangle }}{{\left\langle {P_{IS}^{e} } \right\rangle }}\) for an incident of \(SV\) wave.

Where

The energy is conserved if

where \(E_{{\text{int}}} = \sum\limits_{s,t = 1,s \ne t}^{4} {E_{st} }\) is the resultant interaction energy between the refracted waves.

Discussion and numerical findings

The energy ratios for the incidence longitudinal P wave, thermal T wave, or transversal SV wave at the interface of TS/HPS are computed and plotted graphically with the help of MatLab software for a particular model of TS medium (magnesium) and HPS medium (cadmium selenide). The material parameters of cadmium selenide and magnesium are borrowed from Mondal and Othman46 and Kumar and Sarthi47, as shown in Table 1.

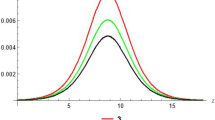

The most notable benefit of this extended model is that it is based on heat transfer with MDD of order (\(n,\,p,\) and \(l\)), and its flexibility in applications due to the free choice of the delay time factor and kernel function as stated earlier in Eqs. (1) and (2) Chiriţă et al.38 show that \(n \ge 5\) or \(p \ge 5\) leads to an unstable system and cannot accurately describe an actual situation. Zampoli48 states that the expansion orders must be less than or equal to 4 for the accompanying models compatible with thermodynamically provided that the correct phase lag time assumptions are made. We choose the kernel function \(K_{i} \left( {t - \zeta } \right) = 1 - {{\left( {t - \zeta } \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {t - \zeta } \right)} \tau }} \right. \kern-0pt} \tau }_{i} ;\,\) \(i = q,\,\,T,\,\,v\) and phase lags \(\tau_{q} = 0.05\,s\), \(\tau_{T} = 0.03s\), \(\tau_{v} = 0.02s\) such that they fulfill the conditions established by Quintanilla and Racke49. To study the impact of higher-order MDD (\(n,\,p,\) and \(l\)) on the variations of the energy ratios, we developed the three different models according to three distinct choices of \(n\),\(p\) and \(l\) such that \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\); \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\); and \(n = p = l = 1\) represented by solid red, green, and blue lines respectively as shown in the Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25. \(E_{RP}\), \(E_{RT}\), and \(E_{RS}\) stand for energy ratios corresponding to reflected P, T, and SV waves, respectively, and \(ES_{i}\); \(i = 1 - 4\) stand for refracted qP, qT, qS, and eP waves, respectively. The overall interaction energy ratio between the various refracted waves is denoted by the \(E_{{\text{int}}}\).

For incident P wave

Figure 2 depicts that for the model \(n = p = l = 1\), the magnitude of \(E_{RP}\) is first decreases gradually with an increased angle of incidence \(0^\circ \le \theta_{0} \le 30^\circ\). After a further increase in the angle of incidence \(30^\circ \le \theta_{0} \le 90^\circ\), the magnitude of \(E_{RP}\) increases monotonically. But in the \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\) and \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) models, we noticed that magnitude of \(E_{RP}\) increases with \(\theta_{0}\), but the increment is slow at near the grazing and normal incidence. P wave reflects more in the \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) model than the other two considered models.

In Fig. 3, we observed that the magnitude of \(E_{RT}\) increases with \(\theta_{0}\) go to maximum and then decreases approaches to zero near the grazing incidence and follow the parabolic path for the \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\) and \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) models. On the other hand, for the \(n = p = l = 1\) model, the magnitude of \(E_{RT}\) approaches zero in a complete range of considered \(\theta_{0}\) but near the grazing incidence magnitude of \(E_{RT}\) increases rapidly.

Figure 4 shows that the magnitude of \(E_{RS}\) first increase with the angle of incidence goes to maximum and then decreases with a further increase of angle of incidence. The magnitude of reflected SV waves is dominated in the \(n = p = l = 1\) model following the \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\) and \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) models. In all considered models, fewer SV waves are reflected near the normal and grazing incidence.

Figures 5, 6, 7 and 8 reveal that the transmitted wave modes, namely, the qS mode, propagate more easily in a piezothermoelastic medium than the other modes. In contrast, qP mode is significantly less excited in the piezothermoelastic medium. Except for the qS mode, all transmitted modes are not excited near the normal incidence. The qT, qS, and eP wave modes are more excited for the \(n = p = l = 1\) model compared to two other considered models in the complete range of angle of incidence. In contrast, initially, the qP wave mode is more enthusiastic in the \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) model but after \(\theta_{0} > 58^\circ\) the \(n = p = l = 1\) model dominates over the other two models.

From Fig. 9, we noticed that the \(E_{{\text{int}}}\) increases with increases angle of incidence up to \(\theta_{0} = 21^\circ\) after that, critical angle interaction energy ratios become positive to negative, and with further increases with angle of incidence, the interaction energy decreases, and at near the grazing incidence, interaction energy again increases.

For incident T wave

In all three models taken into consideration, Fig. 10 demonstrates that the magnitude of \(E_{RP}\) initial rises grows monotonically to a maximum and subsequently declines to a minimum, following a parabolic path with a rising angle of incidence. P waves reflected more readily in the \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\) and \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) models than the \(n = p = l = 1\) model.

Figure 11 shows that in all three considered models, the magnitude of \(E_{RT}\) first monotonically falls approaches zero, with an angle of incidence \(0^\circ \le \theta_{0} \le 45^\circ\), then monotonically grows and reaches unity with the angle of incidence \(45^\circ \le \theta_{0} \le 90^\circ\). Higher order MDD parameters \(n\), \(p\), \(l\) do not seem to have any discernible effects. Figure 12 demonstrates that the magnitude of \(E_{RS}\) the whole range of angle of incidence follows the almost inverted pattern of Fig. 11.

Figures 13 and 14 reveal that as the angle of incidence increases, the magnitude of \(ES_{1}\) and \(ES_{2}\) increases gradually for the \(n = p = l = 1\) model while for the \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\) and \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) models follow the parabolic path whereas around grazing incidence, the magnitude of \(ES_{1}\) and \(ES_{2}\) climb extremely fast in all three considered models. The sub-indent figure of Fig. 13 depicts the magnified image of the overlapping curves to observe the variation in the microscale level. For the \(n = p = l = 1\) model, the transmitted wave modes qP and qT propagate quickly near the grazing incidence compared to the other two models. While in the remaining range of angle of incidence, the magnitude of qP mode in the \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) model dominated over the \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\) model and reversed behavior is observed in the qT mode.

The qS and eP wave modes transfer rapidly in the piezothermoelastic medium at the mid-angle of incidence, as shown in Figs. 15 and 16. On the other hand, qS and eP modes are less excited near the grazing incidence and are not excited near the normal incidence for all three considered models. The magnitude of qS wave mode dominates for the \(n = p = l = 1\) model, followed by the \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\) and \(n = 3\) \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) models. In contrast, the magnitude of eP wave mode dominates for the \(n = p = l = 1\) model, followed by the \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\) and \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) models.

Figure 17 shows that the incidence wave’s interaction energy ratio initially increases to the maximum and then decreases with the angle of incidence. For the \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\) model, the magnitude of \(E_{{\text{int}}}\) most minor compared to the other two models. In the \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) model near the grazing incidence, the magnitude of \(E_{{\text{int}}}\) sharply increases, while in the other two models, it slightly decreases.

For incident SV wave

Figures 18, 19 and 20 reveal that reflected energy ratios \(\left| {E_{RP} } \right|\) and \(\left| {E_{RT} } \right|\) in the range of angle of incidence \(0^{0} \le \theta_{0} \le 58^{0}\) follows the two peaks in contrast \(\left| {E_{RS} } \right|\) trend almost linear and follow the two peaks only for the \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) model. Figures 18 and 19 follow nearly the same pattern, but their magnitudes differ. After the \(\theta_{0} = 58^\circ\), no significant impact of higher-order MDD parameters is observed. For the \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) model, the magnitude of reflected energy ratios is maximum, followed by \(n = p = l = 1\) and \(n = 4\), \(p = 3,\) \(l = 3\) models. But at near grazing incidence, the qT mode is no longer excited. After \(\theta_{0} = 58^\circ\) all the curves overlap, the impact of higher-order parameters has disappeared.

Figures 21, 22, 23 and 24 depict that the magnitude of all transmitted wave modes corresponding to the \(n = p = l = 1\) model lies between the \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\) and \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) models. The qP and qS wave modes quickly propagate in piezothermoelastic medium for \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) model as compared to \(n = p = l = 1\) and \(n = 4\), \(p = 3,\) \(l = 3\) models. On the other hand, reverse behavior is observed for the propagation of the qT wave mode. The qS waves have a critical angle \(\theta_{0} = 37^\circ\). After reaching this critical angle, the qS modes are no longer excited, and the impact of higher-order MDD parameters are disappeared since all curves overlap. As shown in Fig. 24, the electric potential wave does not propagate in a piezothermoelastic material for all investigated models except for the range of angle of incidence \(36^\circ \le \theta_{0} \le 56^\circ\). The eP wave modes are highly stimulated at the angle of incidence \(36^\circ \le \theta_{0} \le 45^\circ\).

Figure 25 illustrates the oscillating and almost reverse pattern seen in Figs. 18, 19, 20 and 21 for interaction energy ratios. The interaction energy changes from negative to positive at an angle of incidence \(\theta_{0} = 40^\circ\). After \(\theta_{0} \ge 58^\circ\), all four models’ curves coincide, as discussed in Figs. 18, 19, 20, 21 and 22. In the case of incidence SV wave as contrary to incidence P or T wave, for all energy ratios, a critical angle \(\theta_{0} = 58^\circ\) is observed in all considered higher-order MDD models. The identification of a critical angle for the incidence of SV waves agrees with the study conducted by Barak et al.17,20.

Conclusion

The thermoelastic plane wave phenomena at an interface between TS and HPS are examined in this study, and the effect of higher-order time differential parameters on energy ratios is studied. The energy ratios of various refracted and reflected waves are calculated using the amplitude ratios for incident P, T, or SV waves. We built three distinct models to investigate the effect of higher-order MDD (\(n\), \(p\), \(l\)) on the variation of the energy ratios according to three different choices of \(n\), \(p\), \(l\) such that \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\); \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\); and \(n = p = l = 1\). Following are some of the findings gleaned from this investigation:

-

The energy ratios are influenced by factors such as the characteristics of the incident wave, higher-order MDD parameters, the angle of incidence, and the material’s physical properties. The nature of this reliance varies for various waves, as seen in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25.

-

For incidence P wave, qS wave mode is highly excited. It easily propagates in the piezothermoelastic medium compared to other transmitted waves, and the magnitude of the reflected P wave is maximum compared to other T or SV waves. The magnitude of all energy ratios for \(n = 4\), \(p = 3\), \(l = 3\) model lies between the \(n = p = l = 1\) and \(n = 3\), \(p = 2\), \(l = 2\) models.

-

For incidence T wave, qP and qT wave modes propagate in piezothermoelastic medium only near the grazing incidence. In contrast, qS and eP wave modes propagate in a mid-angle range of incidence. The negligible impact of higher-order MDD parameters is observed in reflected energy ratios of T and SV waves. In contrast, in other energy ratios, the effect varies with the angle of incidence.

-

For incidence SV wave, near the normal incidence qS wave mode is highly excited and easily propagates in piezothermoelastic medium compared to other transmitted waves. After a particular angle \(\theta_{0} = 58^{0}\), all energy ratios are independent of higher-order MDD parameters, i.e., all three curves overlap.

-

It is discovered that, in all models considered, the total of the energy ratios is almost equal to one at each angle of incidence \(0^\circ \le \theta_{0} \le 90^\circ\). As a result, each model supports the law of energy balance.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information file].

References

Biot, M. A. Thermoelasticity and irreversible thermodynamics. J. Appl. Phys. 27(3), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1722351 (1956).

Lord, H. W. & Shulman, Y. A generalized dynamical theory of thermoelasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 15(5), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5096(67)90024-5 (1967).

Green, A. E. & Lindsay, K. A. Thermoelasticity. J. Elast. 2(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00045689 (1972).

Green, A. E. & Naghdi, P. M. A re-examination of the basic postulates of thermomechanics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 432(1885), 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1991.0012 (1991).

Green, A. E. & Naghdi, P. M. On undamped heat waves in an elastic solid. J. Therm. Stress. 15(2), 253–264 (1992).

Green, A. E. & Naghdi, P. M. Thermoelasticity without energy dissipation. J. Elast. 31(3), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00044969 (1993).

Tzou, D. Y. A unified field approach for heat conduction from macro- to micro-scales. J. Heat Transfer 117, 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2822329 (1995).

Choudhuri, S. R. On a thermoelastic three-phase-lag model. J. Therm. Stress. 30(3), 231–238 (2007).

Wang, J. L. & Li, H. F. Surpassing the fractional derivative: Concept of the memory-dependent derivative. Comput. Math. with Appl. 62(3), 1562–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.camwa.2011.04.028 (2011).

Caputo, M. & Mainardi, F. A new dissipation model based on memory mechanism. Pure Appl. Geophys. 91(1), 134–147 (1971).

Abouelregal, A. E., Ahmad, H. & Yao, S. W. Functionally graded piezoelectric medium exposed to a movable heat flow based on a heat equation with a memory-dependent derivative. Materials 13(18), 3953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13183953 (2020).

Wang, J. L. & Li, H. F. Memory-dependent derivative versus fractional derivative (I): Difference in temporal modeling. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 384, 112923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cam.2020.112923 (2021).

Wang, J. L. & Li, H. F. Memory-dependent derivative versus fractional derivative (II): Remodelling diffusion process. Appl. Math. Comput. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2020.125627 (2021).

Mindlin, R. D. Equations of high frequency vibrations of thermopiezoelectric crystal plates. Int. J. Solids Struct. 10(6), 625–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7683(74)90047-X (1974).

Nowacki, W. Some general theorems of thermopiezoelectricity. J. Therm. Stress. 1(2), 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495737808926940 (1978).

Chandrasekharaiah, D. S. A generalized linear thermoelasticity theory for piezoelectric media. Acta Mech. 71(1–4), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01173936 (1988).

Barak, M. S., Kumar, R., Kumar, R. & Gupta, V. Energy analysis at the boundary interface of elastic and piezothermoelastic half-spaces. Indian J. Phys. 97(8), 2369–2383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12648-022-02568-w (2023).

Gupta, V., Kumar, R., Kumar, R. & Barak, M. S. Energy analysis at the interface of piezo/thermoelastic half spaces. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 33(6), 2250–2277. https://doi.org/10.1108/HFF-11-2022-0654 (2023).

Gupta, V., Kumar, R., Kumar, M., Pathania, V. & Barak, M. S. Reflection/transmission of plane waves at the interface of an ideal fluid and nonlocal piezothermoelastic medium. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 33(2), 912–937. https://doi.org/10.1108/HFF-04-2022-0259 (2023).

Barak, M. S., Kumar, R., Kumar, R. & Gupta, V. The effect of memory and stiffness on energy ratios at the interface of distinct media. Multidiscip. Model. Mater. Struct. 19(3), 464–492. https://doi.org/10.1108/MMMS-10-2022-0209 (2023).

Gupta, V. & Barak, M. S. Quasi-P wave through orthotropic piezo-thermoelastic materials subject to higher order fractional and memory-dependent derivatives. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376494.2023.2217420 (2023).

Yadav, A. K., Barak, M. S. & Gupta, V. Reflection at the free surface of the orthotropic piezo-hygro-thermo-elastic medium. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 1293(0003), 3535–3560. https://doi.org/10.1108/HFF-04-2023-0208 (2023).

Gupta, V. & Barak, M. S. Fractional and MDD analysis of piezo-photo-thermo-elastic waves in semiconductor medium. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376494.2023.2238201 (2023).

Barak, M., Kumari, M. & Kumar, M. Effect of hydrological properties on the energy shares of reflected waves at the surface of a partially saturated porous solid. AIMS Geosci. 3(1), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.3934/geosci.2017.1.67 (2017).

Kumar, M., Kumari, M. & Barak, M. S. Reflection of plane seismic waves at the surface of double-porosity dual-permeability materials. Pet. Sci. 15(3), 521–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-018-0245-y (2018).

Kumar, M., Barak, M. S. & Kumari, M. Reflection and refraction of plane waves at the boundary of an elastic solid and double-porosity dual-permeability materials. Pet. Sci. 16(2), 298–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-018-0289-z (2019).

Kumar, M., Singh, A., Kumari, M. & Barak, M. S. Reflection and refraction of elastic waves at the interface of an elastic solid and partially saturated soils. Acta Mech. 232(1), 33–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-020-02819-z (2021).

Li, C., Guo, H., Tian, X. & He, T. Size-dependent thermo-electromechanical responses analysis of multi-layered piezoelectric nanoplates for vibration control. Compos. Struct. 225, 111112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.111112 (2019).

Li, C., Tian, X. & He, T. An investigation into size-dependent dynamic thermo-electromechanical response of piezoelectric-laminated sandwich smart nanocomposites. Int. J. Energy Res. 45(5), 7235–7255. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.6308 (2021).

Li, C., Tian, X. & He, T. New insights on piezoelectric thermoelastic coupling and transient thermo-electromechanical responses of multi-layered piezoelectric laminated composite structure. Eur. J. Mech. A/Solids 91, 104416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euromechsol.2021.104416 (2022).

Li, C., Guo, H., He, T. & Tian, X. A rate-dependent constitutive model of piezoelectric thermoelasticity and structural thermo-electromechanical responses analysis to multilayered laminated piezoelectric smart composites. Appl. Math. Model. 112, 18–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2022.07.025 (2022).

Chiriţă, S. On high-order approximations for describing the lagging behavior of heat conduction. Math. Mech. Solids 24(6), 1648–1667. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081286518758356 (2019).

Abouelregal, A. E. A novel generalized thermoelasticity with higher-order time-derivatives and three-phase lags. Multidiscip. Model. Mater. Struct. 16(4), 689–711. https://doi.org/10.1108/MMMS-07-2019-0138 (2020).

Abouelregal, A. E. Three-phase-lag thermoelastic heat conduction model with higher-order time-fractional derivatives. Indian J. Phys. 94(12), 1949–1963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12648-019-01635-z (2020).

Abouelregal, A. E., Moustapha, M. V., Nofal, T. A., Rashid, S. & Ahmad, H. Generalized thermoelasticity based on higher-order memory-dependent derivative with time delay. Results Phys. 20, 103705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103705 (2021).

Abouelregal, A. E., Civalek, Ö. & Oztop, H. F. Higher-order time-differential heat transfer model with three-phase lag including memory-dependent derivatives. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 128(October), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2021.105649 (2021).

Barak, M. S. & Gupta, V. Memory-dependent and fractional order analysis of the initially stressed piezo-thermoelastic medium. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376494.2023.2211065 (2023).

Chiriţă, S., Ciarletta, M. & Tibullo, V. On the thermomechanical consistency of the time differential dual-phase-lag models of heat conduction. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 114, 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2017.06.071 (2017).

Tzou, D. Y. Experimental support for the lagging behavior in heat propagation. J. Thermophys. Heat Transf. 9(4), 686–693. https://doi.org/10.2514/3.725 (1995).

Ezzat, M. A., El-Karamany, A. S. & El-Bary, A. A. On dual-phase-lag thermoelasticity theory with memory-dependent derivative. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 24(11), 908–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376494.2016.1196793 (2017).

Abouelregal, A. E. An advanced model of thermoelasticity with higher-order memory-dependent derivatives and dual time-delay factors. Waves Random Complex Media https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2020.1871110 (2021).

Ghosh, D., Das, A. K. & Lahiri, A. Modelling of a three dimensional thermoelastic half space with three phase lags using memory dependent derivative. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 5(6), 154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40819-019-0731-y (2019).

Slaughter, W. S. The Linearized Theory of Elasticity (Birkhäuser Boston, 2002).

Achenbach, J. D. Wave Propagation in Elastic Solids (Elsevier, 1975).

Kumar, R. & Sharma, P. Response of two-temperature on the energy ratios at elastic-piezothermoelastic interface. J. Solid Mech. 13(2), 186–201. https://doi.org/10.22034/JSM.2020.1907521.1637 (2021).

Mondal, S. & Othman, M. I. A. Memory dependent derivative effect on generalized piezo-thermoelastic medium under three theories. Waves Random Complex Media 31(6), 2150–2167. https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2020.1730480 (2021).

Kumar, R. & Sarthi, P. Reflection and refraction of thermoelastic plane waves at an interface between two thermoelastic media without energy dissipation. Arch. Mech. 58(2), 155–185 (2006).

Zampoli, V. On the increase in signal depth due to high-order effects in micro-and nanosized deformable conductors. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2629012 (2019).

Quintanilla, R. & Racke, R. A note on stability in three-phase-lag heat conduction. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 51(1–2), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2007.04.045 (2008).

Acknowledgements

Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2023R576), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This project is funded by King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Barak is involved in conceptualization and methodology. Gupta took charge of the software development and writing of the original draft. Ahmad provided supervision and conducted the investigation. Rajneesh Kumar contributed to the software development and performed validation. Rajesh Kumar, played the role of writing, reviewing, and editing. Awwad and Ismail worked together to respond to the valuable comments from the esteemed reviewers.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barak, M.S., Ahmad, H., Kumar, R. et al. Behavior of higher-order MDD on energy ratios at the interface of thermoelastic and piezothermoelastic mediums. Sci Rep 13, 17170 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44339-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44339-5

This article is cited by

-

Effects of Rotation and Nonlocality on the Thermoelastic Behavior of Micropolar Materials in the 3PHL Model

Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Mechanical Engineering (2025)

-

Advanced Thermoelastic Modeling of Porous Materials with Dual-Phase Lag and Memory-Dependent Effects

Journal of Vibration Engineering & Technologies (2025)

-

Fractional-order Photo-thermoelastic Model for Laser-induced Dynamic Response in Sandwich Laminated Semiconductor Composites

Silicon (2025)

-

Response of Moisture and Temperature Diffusivity on an Orthotropic Hygro-thermo-piezo-elastic Medium

Journal of Nonlinear Mathematical Physics (2024)

-

The effect of viscosity and hyperbolic two-temperature on energy ratios in elastic and piezoviscothermoelastic half-spaces

Mechanics of Time-Dependent Materials (2024)