Abstract

Our work reports implementation of a useful genetic diagnosis for the clinical managment of patients with astrocytic tumors. We investigated 313 prospectively recruited diffuse astrocytic tumours by applying the cIMPACT-NOW Update 3 signature. The cIMPACT-NOW Update 3 (cIMPACT-NOW 3) markers, i.e., alterations of TERT promoter, EGFR, and/or chromosome 7 and 10, characterized 96.4% of IDHwt cases. Interestingly, it was also found in 48,5% of IDHmut cases. According to the genomic profile, four genetic subgroups could be distinguished: (1) IDwt/cIMPACT-NOW 3 (n = 270); (2) IDHwt/cIMPACT-NOW 3 negative (= 10); (3) IDHmut/cIMPACT-NOW 3 (n = 16); and 4) IDHmut/cIMPACT-NOW 3 negative (n = 17). Multivariate analysis confirmed that IDH1/2 mutations confer a favorable prognosis (IDHwt, HR 2.91 95% CI 1.39–6.06), and validated the prognostic value of the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature (cIMPACT-NOW 3, HR 2.15 95% CI 1.15–4.03). To accurately identify relevant prognostic categories, overcoming the limitations of histopathology and immunohistochemistry, molecular-cytogenetic analyses must be fully integrated into the diagnostic work-up of astrocytic tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The evaluation and diagnostic application of molecular-cytogenetic markers, in astrocytic and oligodendroglial tumors, is rapidly evolving and sees the introduction of a relatively large number of genetic markers, in the fifth Edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification for Central Nervous System Tumors (CNS)1,2. Starting from the work of the Consortium to Inform Molecular and Practical Approaches to CNS tumours (cIMPACT-NOW Updates), new alterations have been recognized to be of diagnostic and clinical value. Indeed, although grading has exclusively relied on histopathological features, molecular-cytogenetics have already provided useful predictive and/or prognostic information1,3. In addition, as different oncogenic events are associated with clinical and pathological features that define distinct entities, new tumor types and subtypes have been introduced1. As for gliomas, glioneuronal tumors, and neuronal tumors, these have been reclassified into six families, including "diffuse adult-type gliomas," which account for the vast majority of primary brain tumors in adults.

It is worth noting that EGFR amplification, gain of chromosome 7, monosomy 10, PTEN mono- or bi- allelic deletions, and mutations of TERT promoter (TERTp), typically occur in grade IV, i.e. glioblastoma (GBM), and in IDH1/2-wildtype (IDHwt) grade II/III, i.e. diffuse/anaplastic astrocytomas (DA/AA), where their prognostic impact is still debated4,5,6. In 2018 Stichel et al. first proposed the use of these markers as prognostic factors to improve patient risk assignment7. Afterwards, the cIMPACT-NOW Update 3 consortium, has recommended their employment to define a high risk signature, valuable to fine tune the classification of IDHwt DA/AA8. Accordingly, cases harboring EGFR amplification, and/or gain of chromosome 7 plus monosomy 10 (+ 7/− 10), and/or TERTp mutations, have to be referred to as “astrocytic gliomas, IDHwt, with molecular features of GBM grade IV”8. This signature would overtake histopathology and immunohistochemistry, deeply modifying the currently adopted risk stratification criteria for IDHwt DA/AA9. However, implementation of these bio-molecular criteria for routine diagnostics of glioma tumors is still not widely applied.

Starting from our "real-life" experience, we sought to assess the correlation between genomic profile and disease outcome in adult patients with glial tumors based on data obtained from the application of a multidisciplinary diagnostic approach that included cytogenetic and molecular characterization. Our data set on 313 cases confirmed the favorable prognostic value of IDH1/2 mutations, and validated the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature as high-risk marker, thus confirming prognostically relevant subgroups.

Materials and methods

Patient cohort

All patients prospectively admitted to the Neurosurgery department of our Regional Hospital and referred to the Molecular Medicine Laboratory (Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Perugia), for molecular-cytogenetic diagnosis, were included in the study (timeframe: from August 2010 to July 2020). Overall, 313 patients were recruited. There were 184 males and 129 females. The median age, at diagnosis, was 64 years (range 23–83); the median follow-up was 10.9 with a range of 0.2–168 months. Survival was measured from the date of histopathological diagnosis until death, or was censored at the date of last follow-up. Median follow-up was 18.3 months: 24.3 for DA/AA and 9.6 for GBM.

In all cases the backbone of treatment was based on alkylating agents and/or radiotherapy except for 41 patients with multifocal diffuse disease and compromised clinical conditions, who died within 3 months from diagnosis. Timing, dosing, and scheduling were determined based on age, Karnofsky performance status, size of residual tumour, and presence of multifocal lesions. Radiotherapy started within 3–5 weeks after surgery, at a dosage of 50–60 Gy in 1.8–2 Gy, daily fractions. In fit patients, aged less than 70 years, temozolomide was concomitantly administered at 75 mg/m2 daily dosage, plus at least six cycles of maintenance (150–200 mg/m2, 5 out of 28 days)10. Patients with DA/AA were treated with radiotherapy alone or in combination with alkylating agents (temozolomide, lomustine, or carmustine)11,12. Molecular cytogenetic studies were done on paraffin-embedded biopsies taken at the time of diagnosis. Analyses were performed on representative areas as indicated by Pathologists.

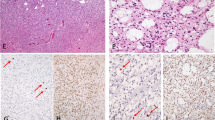

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Numerical and structural chromosome abnormalities were investigated by FISH on 4 μm Formalin-Fixed Paraffin Embedded (FFPE) cerebral tissue sections, after automated chemical pretreatment by ThermoBrite Elite (Leica, Milan, Italy). Commercially available genomic probes were applied to study EGFR amplification and chromosome 7 numerical abnormalities (LSI EGFR Spectrum orange/CEP 7 Spectrum green probe, Vysis-Abbott Milan, Italy), PTEN deletions and chromosome 10 numerical abnormalities (LSI PTEN Spectrum orange/CEP 10 Spectrum green probe, Vysis-Abbott), and codeletion of 1p and19q (codel1p/19q) (LSI 1p36 SpectrumOrange/1q25 SpectrumGreen Probes and s LSI 19q13 SpectrumOrange/19p13 SpectrumGreen Probes, Vysis-Abbott). Analyses were carried out on areas with > 50% of infiltrating neoplastic cells, using an Olympus BX61 fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Milan, Italy) equipped with a highly sensitive JAI camera (Copenhagen, Denmark) and driven by CytoVision 4.5.4 software (Genetix, New Milton, Hampshire, UK). To avoid missing of small abnormal clones, microscopic analysis of the entire hybridization area (18 × 18), and evaluation of at least 200 cells, was performed. Cut-off for analyses were set as follows: EGFR amplification ≥ 3% of analyzed cells, chromosome 7 gain ≥ 10%, PTEN deletion/monosomy 10 ≥ 20%13.

Sanger sequencing

Genomic DNA, extracted from 8 μm FFPE brain tumor sections using an automatized Qiacube system and the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Milan, Italy) and investigated for IDH1 (exon 4, 385 bp), IDH2 (exon 4, 312 bp), and core TERT promoter (TERTp) hot-spot mutations by ABI 3500 Genetic analyzer instrument (Applied Biosystems, Monza, Italy). The primer design has already been reported by Pierini et al.13 and was referred to the GRCh37 genomic coordinate system: NM_005896.3 for IDH1, NM_002168.3 for IDH2, and NM_000005.9 for core TERTp. Sequence analysis was performed with EditSeq DNAstar and FinchTV1 software, and alignment was supported by Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo), and the analysis of variants by Ensembl (http://www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens), Varsome (https://varsome.com), and COSMIC (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic) websites.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated including frequencies, percentages, frequency tables for categorical variables, median and means ± standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables. Categorical variables were evaluated by Chi-square or Fisher's exact test when appropriate. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to analyze Overall survival (OS) and estimate medians with two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI). Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Cox regression model was applied to estimate Hazard Ratio (HR) and 95% CI and to identify prognostic factors independently associated with survival times. To test proportional hazard (PH) assumption log-minus-log plots was used14. Stepwise backward-selection was used for eliminates variables from the regression model to find a reduced model that best explains the data15. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA v. 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics aproval and consent to particpate

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and it was approved by the Umbria region ethic committee, code number 2843/16 on August 8th, 2016. Informed consent, regarding data was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Results

The genomic profile of glioma tumours

Cases were first classified on the basis of histopathological and immunohistochemistry features as GBM (276), AA (17), and DA (20) (Table 1)2. According to the status of IDH1/2 genes, there were 280 IDH wildtype (IDHwt) cases, including 267 GBM, 8 DA, and 5 AA, and 29 IDH-mutant (IDHmut), which harbored IDH1R132, IDH2R140, or IDH2R1721. They were 5 GBM, 12 DA, and 12 AA (Table 1). In addition, 4 cases had non-canonical IDH1 or IDH2 mutations (cases nos. 3, 4, 6, and 9, Table 2). These mutations were all located within the hot-spot region (exon 4), were not reported as polymorphisms, and were predicted to be pathogenic/likely pathogenic and/or described as somatic in other tumor types (Table 2)16,17,18,19. Therefore, since cases with non-canonical IDH1/IDH2 mutations could not be definitively considered IDHwt, we grouped them with IDHmut cases, while not strictly applying the WHO criteria1. Altogether, in our case series a total of 33 cases were considered to be IDHmut.

Overall, EGFR amplification (EGFR ampl) was detected in 111/306, gain of chromosome 7 in 174/306, and TERTp mutations in 250/313. Monosomy of chromosome 10 was found in 209/300 cases while mono- and/or bi- allelic deletion of PTEN in 19/300. We observed that high risk molecular-cytogenetic markers were unequally distributed among GBM and DA/AA. In GBM, EGFR ampl was detected in 105/276, monosomy of chromosome 10/PTEN deletion in 212/276, gain of chromosome 7 in 147/276, TERTp mutations in 237/276; in DA and AA, EGFR ampl was found in 6/37 (4/20 DA and 2/17 AA), gain of chromosome 7 in 27/37 (13/20 DA and 14/17 AA), monosomy of chromosome 10/PTEN deletion in 16/36 (8/19 DA and 8/17 AA), TERTp mutations in 13/37 (7/20 DA and 6/17 AA) cases.

By applying the cIMPACT-NOW Update 3 signature, 270 cases were reclassified as “Diffuse astrocytic glioma, IDH-wt, with molecular features of glioblastoma, WHO grade IV” due to the presence of at least one of biomolecular markers that define the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature. All 13 IDHwt DA/AA cases, 11 of whom had at least 2 high-risk cIMPACT-NOW markers and none had an isolated TERTp mutation, belonged to this subgroup.

The cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature also characterized 16/33 IDHmut cases (4 DA, 5 AA and 7 GBM) (Table 2). There were 9 cases with + 7/− 10, 1 case with EGFR amplification, and 2 cases with TERTp mutations. In the remaining 4 cases, 2 concomitant high-risk markers were detected: + 7/− 10 and TERTp mutations (= 2) or EGFR amplification and TERTp mutations (= 2). In all cases, the absence of codel1p/19q excluded the diagnosis of oligodeldroglioma1,2,20,21. On the other hand, the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature was not found in 10 patients with IDH1wt GBM (Table 3) showing the typical morphology of diffuse astrocytic tumors, with microvascular proliferation and/or palisade necrosis1,2.

Genomic features and survival

According to genetic profile the entire cohort of cases was re-classified in four subgroups: (1) IDHwt/cIMPACT 3 (= 270); (2) IDHwt/cIMPACT 3 negative (= 10); (3) IDHmut/cIMPACT 3 negative (= 17); and (4) IDHmut/cIMPACT 3 (= 16) (Fig. 1A). While the cIMPACT 3 signature, the IDH status and age, were all strong predictors of outcome, histopathology and immunohistochemistry lost their prognostic significance.

The IDH status was confirmed to be a robust prognostic marker (IDHwt, HR 2.91 95% CI 1.39–6.06) distinguishing two relevant risk subgroups. We also validated the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature as an additional prognostic marker which improved the stratification of IDHwt tumours (cIMPACT-NOW 3, HR 2.15 95% CI 1.15–4.03). Indeed, the probability of overall survival was significantly lower in cIMPACT-NOW 3 positive (high risk subgroup) than in IDHwt cIMPACT-NOW 3 negative tumours (low risk subgroup) (Fig. 1B).

The 13 IDHwt DA/AA cases that belonged to the cIMPACT-NOW 3 high risk subgroup showed a median overall survival (8.8 months; range 10–47) similar to GBM cases, although the two medians were statistically different probably due to the limited number of these rare cases. In addition, 12/13 patients died from disease progression. Instead, the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature did not appear to be prognostically relevant in IDHmut cases (Table 2). On the other hand, according to the overall survival, the cIMPACT-NOW 3 negative GBM cases, either IDHwt (Table 3) or IDHmut, could be probably relocated into a more favorable risk subgroup (median overall survival: 55.8 months (29.5-not reached).

Discussion

Our study, conducted on a prospectively recruited case series, has the strength to broadly represent the incidence and distribution of recurrent astrocytic tumors in adult subjects in the real world. Indeed, as expected in adults, the number of patients with low grade IDHmut tumors was rather low. Thus, we are aware that this type of study might cause a bias in the analysis of patient survival related to differences in treatment and underrepresentation of rare tumor subtypes. On the other hand, the study precisely reflects the epidemiological features of astrocytic tumors in adults. In addition, as a long-term follow-up was available, the outcome of long-term survivors could be precisely determined. Overall, results from our study further support the rationale for incorporating the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature as diagnostic criteria for glioblastoma1.

We confirmed that both IDH status and cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature are valid prognostic markers for risk stratification of patients and also provided new insights to consider for reclassification of low-risk cases.

As expected, the IDH status was found to be a robust prognostic marker distinguishing two relevant risk subgroups. Then to determine the impact of the genomic profile on overall survival, we assessed how the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature was distributed into IDHwt and IDHmut cases. As expected, the large majority of IDHwt cases were characterized by high risk signature. In particular, 92.6% cases were positive for at least two markers, and TERTp mutations were detected in 90% cases. Interestingly, 10 (~ 3.5%) IDHwt GBM did not harbor the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature.

Survival analysis clearly indicated that the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature is an additional prognostic marker suitable to improve the risk stratification of IDHwt cases. In fact, the probability of overall survival was significantly lower in cases with the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature than in cases without this high-risk marker.. Notably, all the 13 IDHwt DA/AA belonged to the cIMPACT-NOW 3 high risk subgroup and showed a median overall survival similar to GBM cases. This is probably due to the genomic profile of our IDHwt DA/AA cases, which never had the isolated TERTp variants and showed 2–3 high-risk markers. Similarly, Berzero et al.22 reported that astrocytomas with 2–3 molecular traits of the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature had a more severe prognosis. However, they also showed that high risk markers are unequally distributed among grade II and grade III astrocytoma and that isolated TERTp mutations were not predictive of poor outcome22.

Other groups have shown that glioma cases with gain of 7p, loss of 10q, and mutation in the TERT promoter biologically represent a different subtype, which is prognostically relevant and has clinical impact for proper risk stratification of patients and choice of treatment23,24,25. On the other hand, we and others have observed that IDHwt GBM without the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature behaved as low risk gliomas showing a long survival.

These findings, based on data from real-world diagnostic activity, further highlight the inherent limitations of histopathology and immunohistochemistry in the classification of glial tumors, and indicate the need for comprehensive characterization to properly stratify patients at the time of diagnosis. They are in line with other studies that have shown that IDHwt astrocytomas are more likely to behave like GBM, even in the absence of a high-risk molecular profile24,26. However, to confirm these data, large multicenter prospective studies need to be conducted.

Thus, while the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature, the IDH status and age, were all strong predictors of outcome, histopathology and immunohistochemistry lost their prognostic significance. By introducing genetics among the dignostic criteria, the fifth edition of the WHO classification1 established that regardless of histopathology, cases with high-risk molecular markers should be classified as GBM IDHwt. Instead, according to the overall survival, GBM cases, either IDHwt or IDHmut, not harboring this high risk signature, could be relocated into a more favorable risk subgroup.

Although the cIMPACT-NOW 3 signature was recommended to refine the classification of IDHwt gliomas, we sought to assess whether it also occurred in cases with IDH1/2 mutations and if it impacts upon prognosis in this subgroup of gliomas. Unexpectedly, roughly 48% of IDHmut cases harbored cIMPACT-NOW 3 markers which however did not appear to be prognostically relevant in this subgroup of tumors.

In conclusion, as recommended by the last updated WHO classification for CNS tumors, to accurately identify relevant prognostic categories, overcoming the limitations of histopathology and immunohistochemistry, a comprehensive molecular-cytogenetic approach must be considered in the diagnostic work-up of this subgroup of human cancers. Remarkably, more than 20 genes/pathways have been proposed to refine the classification of specific nosological entities in the context of gliomas and astrocytic gliomas in children and adults1. Defining the genomic profile of glioma tumours is not only required to predict response to chemo-/radio- therapy and life expectancy of patients, but also to provide the molecular basis for tailored treatments.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not available in the repository, but will be provided in excel format if requested, at any moment, at email adress alessio.gili@unipg.it.

References

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Central Nervous System Tumours (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2016).

Louis, D. N. et al. World Health Organization Histological Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2016).

Louis, D. N. et al. cIMPACT-NOW: A practical summary of diagnostic points from Round 1 updates. Brain Pathol. 29(4), 469–472 (2019).

Brito, C. et al. Clinical insights gained by refining the 2016 WHO classification of diffuse gliomas with: EGFR amplification, TERT mutations, PTEN deletion and MGMT methylation. BMC Cancer 19, 968 (2019).

Kuwahara, K. et al. Clinical, histopathological, and molecular analyses of IDH-wild-type WHO grade II-III gliomas to establish genetic predictors of poor prognosis. Brain Tumor Pathol. 36, 135–143 (2019).

Lee, Y. et al. The frequency and prognostic effect of TERT promoter mutation in diffuse gliomas. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 5, 62 (2017).

Stichel, D. et al. Distribution of EGFR amplification, combined chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss, and TERT promoter mutation in brain tumors and their potential for the reclassification of IDHwt astrocytoma to glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 136, 793–803 (2018).

Brat, D. J. et al. cIMPACT-NOW update 3: recommended diagnostic criteria for “Diffuse astrocytic glioma, IDH-wildtype, with molecular features of glioblastoma, WHO grade IV”. Acta Neuropathol. 136, 805–810 (2018).

Tesileanu, C. M. S. et al. Survival of diffuse astrocytic glioma, IDH1/2 wildtype, with molecular features of glioblastoma, WHO grade IV: A confirmation of the cIMPACT-NOW criteria. Neuro Oncol. 22, 515–523 (2020).

Stupp, R. et al. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 987–996 (2021).

van den Bent, M. J. et al. Interim results from the CATNON trial (EORTC study 26053–22054) of treatment with concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide for 1p/19q non-co-deleted anaplastic glioma: A phase 3, randomised, open-label intergroup study. Lancet 390, 1645–1653 (2017).

Weller, M. et al. EANO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse gliomas of adulthood. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 170–186 (2021).

Guerriero, A. et al. Metachronous cardiac and cerebral sarcomas: Case report with focus on molecular findings and review of the literature. Hum. Pathol. 46, 482–487 (2015).

Grambsch, P. M. & Therneau, T. M. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 81, 515–526 (1994).

Halinski, R. S. & Feldt, L. S. The selection of variables in multiple regression analysis. J. Educ. Meas. 7, 151–157 (1970).

Giannakis, M. et al. Genomic correlates of immune-cell infiltrates in colorectal carcinoma. Cell Rep. 15, 857–865 (2016).

Uson Junior, P. L. S. & Borad, M. J. Clinical utility of ivosidenib in the treatment of IDH1-mutant cholangiocarcinoma: Evidence to date. Cancer Manag Res. 15, 1025–1031 (2023).

Vihinen, M. When a synonymous variant is nonsynonymous. Genes (Basel). 13, 1485 (2022).

Mouradov, D. et al. Colorectal cancer cell lines are representative models of the main molecular subtypes of primary cancer. Cancer Res. 74, 3238–3247 (2014).

Arita, H. et al. TERT promoter mutation confers favorable prognosis regardless of 1p/19q status in adult diffuse gliomas with IDH1/2 mutations. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 23, 201 (2020).

Arita, H. et al. Upregulating mutations in the TERT promoter commonly occur in adult malignant gliomas and are strongly associated with total 1p19q loss. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 267–276 (2013).

Berzero, G. et al. IDH-wildtype lower-grade diffuse gliomas: The importance of histological grade and molecular assessment for prognostic stratification. Neuro-Oncology 23, 955–966 (2021).

Kumari, K. et al. Molecular characterization of IDH wild-type diffuse astrocytomas: The potential of cIMPACT-NOW guidelines. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 30, 410–417 (2022).

Aoki, K. et al. Prognostic relevance of genetic alterations in diffuse lower-grade gliomas. Neuro-Oncology 20, 66–77 (2018).

Makino, Y. et al. Prognostic stratification for IDH-wild-type lower-grade astrocytoma by Sanger sequencing and copy-number alteration analysis with MLPA. Sci. Rep. 11, 14408 (2021).

Lee, D., Riestenberg, R. A., Haskell-Mendoza, A. & Bloch, O. Diffuse astrocytic glioma, IDH-Wildtype, with molecular features of glioblastoma, WHO grade IV: A single-institution case series and review. J. Neurooncol. 152, 89–98 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to all the patients included and their clinicians in charge.

Funding

This study was supported jointly by Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Perugia-Italy (Grant number: 2018.0418.021), by Comitato per la vita “Daniele Chianelli” (Perugia, Italy), and “Sergio Luciani” Association (Fabriano, Italy).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.L.S. conceived the study; R.L.S., C.N., and T.P. planned experiments and performed data analysis; R.L.S. and A.G. wrote the paper; S.A., D.B., and E.M. performed DNA extraction and FISH experiments; T.P., C.N., E.M., and P.G. performed sequencing analysis; P.G. and M.M. performed histology and immunohistochemistry and central revision of cases; A.G. conducted the statistical analysis; C.M., F.R., R.C., G.M., C.C., N.N. and M.L. provided clinical data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All patients enrolled in this study gave their consent to publish their clinical data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Molica, C., Gili, A., Nardelli, C. et al. Optimizing the risk stratification of astrocytic tumors by applying the cIMPACT-NOW Update 3 signature: real-word single center experience. Sci Rep 13, 20101 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46701-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46701-z