Abstract

It is unclear whether manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) following primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is effective in reducing pain and swelling and improving knee function. The present study investigated the efficacy of MLD after TKA. The outcomes of interest are the range of motion (ROM), pain (visual analogue scale, VAS), and circumference of the lower leg. This meta-analysis was conducted according to the 2020 PRISMA statement. In November 2023, the following databases were accessed: PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Embase, with no time constraint. Only level I evidence studies, according to the Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine, were considered. All the randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing patients who have received MLD versus a group of patients who did not undergo MLD following primary TKA were accessed. Data from four RCTs (197 TKAs) were retrieved. 67% (132 of 197 patients) were women. The mean length of follow-up was 7.0 ± 5.8 weeks. The mean age of the patients was 69.6 ± 2.7 years, and the mean BMI was 28.7 ± 0.9 kg/m2. At baseline, between-group comparability was evidenced in the male:female ratio, mean age, mean BMI, knee flexion, and VAS. No difference was found in flexion (P = 0.7) and VAS (P = 0.3). No difference was found in the circumference of the thigh (P = 0.8), knee (P = 0.4), calf (P = 0.4), and ankle (P = 0.3). The current level I of evidence does not support the use of MLD in primary TKA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In patients with end-stage osteoarthritis1,2, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is commonly performed3,4,5. TKA restores joint function, improving the quality of life and participation in recreational activities6,7,8,9,10,11. In the past few decades, the number of patients undergoing TKAs has increased, and the design and techniques also developed quickly to ensure the highest standards12,13,14,15,16,17. Postoperative rehabilitation to favor and embrace recovery following TKA is debated18,19. Several studies investigated methods to improve function and shorten the time to full recovery, starting rehabilitation in the first postoperative days20,21,22,23,24,25,26. In this context, manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) has been advocated in this phase of postoperative recovery to reduce oedema and pain27,28,29. The principle behind MLD is the stimulation and improvement of the lymphatic system, promoting variations in interstitial pressures through the application of gentle pressure27,28. Regarding the potential effect of MLD on pain, the exact mechanism is not yet clear, and the placebo effect may play a major role30,31. However, whether MLD is effective in reducing pain and swelling and improving knee function is still unclear and evidence is controversial. Recently, four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which evaluated the efficacy of MLD in TKA have been published32,33,34,35; however, to the best of our knowledge, an updated meta-analysis is missing.

The present study investigated the efficacy of MLD after TKA. The outcomes of interest are the range of motion (ROM), pain, and circumference of the lower leg.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

All the clinical studies comparing MLD versus a group of patients who did not undergo MLD following TKA were accessed. Only studies published in peer-reviewed journals were considered. According to the author’s language capabilities, articles in English, German, Italian, French, and Spanish were eligible. Only level I of evidence studies, according to the Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine36, were considered. Studies which evaluated arthroplasty in other body areas were not considered, nor were those conducted in TKA revision settings. Reviews, opinions, letters, and editorials were not considered. Missing quantitative data under the outcomes of interests warranted the exclusion of the study. Only studies that clearly stated the sample size were considered.

Search strategy

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the 2020 PRISMA statement37. The PICOD algorithm was preliminarily established:

-

1.

P (Problem): postoperative recovery in TKA.

-

2.

I (Intervention): MLD.

-

3.

C (Control): non-MLD.

-

4.

O (Outcomes): ROM, pain, and swelling.

-

5.

D (Design): RCT.

In November 2023, the following databases were accessed: PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Embase. No time constraint was set for the search. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) used for the database search are reported as supplementary material. The search was restricted to RCTs.

Selection and data collection

Selection and data collection were performed by two authors (L.S. & R.G.). All the titles resulting from the literature search were screened by hand and the abstract of those which matched the topic were accessed. If the abstract matched the topic, the full text was accessed. Moreover, the same authors conducted a cross-reference of the bibliography of the full texts for inclusion. A third senior author (N.M.) took the final decision in case of divergencies.

Data items

Two authors (L.S. & R.G.) performed data extraction. The following data at baseline were extracted: author, year of publication and journal, length of the follow-up, number of patients with related mean age, and BMI. Data concerning knee flexion and Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) were collected at baseline and last follow-up. Data on the circumference of the lower leg (tight, knee, calf, ankle) at last follow-up were collected. Data were extracted in Microsoft Office Excel version 16.72 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA).

Assessment of the risk of bias and quality of the recommendations

The risk of bias was evaluated following the guidelines Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions38. One reviewer (L.S.) evaluated the risk of bias in the extracted studies using the risk of bias assessment tool (RoB2)39,40 of the software Review Manager 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen). The following endpoints were evaluated: bias arising from the randomisation process, bias from deviations from intended interventions, bias from missing outcome data, bias in measurement of the outcome, and bias in selection of the reported result.

Synthesis methods

The statistical analyses were performed by the main author (F.M.) following the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions41. To assess data distribution the Saphiro–Wilk test was used. For parametric data, the mean value and standard deviation (SD) were calculated. For non-parametric data, the median value and interquartile range (IQR) were evaluated. To assess baseline comparability, the unpaired t-test for parametric data or the Mann–Whitney test for non-parametric variables were used. The meta-analyses were conducted using the software Review Manager 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen). For continuous data, the inverse variance method with mean difference (MD) effect measure was used. For dichotomic data, the Mantel–Haenszel method with odd ratio (OR) effect measure was used. The CI was set at 95% in all the comparisons. Heterogeneity was evaluated through Higgins-I2 and χ2 tests. If Pχ2 > 0.05, no statistically significant heterogeneity was found. If Pχ2 < 0.05, the heterogeneity was estimated using the Higgins-I2 as follows: low (< 30%), moderate (30% to 60%), and high (> 60%). A fixed effect model was set as default. If moderate or high heterogeneity was detected, a random model effect was used. Overall values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

This study complies with ethical standards.

Results

Study selection

The systematic literature search resulted in 280 articles. A total of 59 duplicates were identified and therefore removed. After reviewing the abstracts of the remaining 221 studies, a further 184 articles were discarded because they did not match the eligibility criteria. The detailed reasons leading to exclusion were: study type and design (N = 108), low level of evidence (N = 53), full-text not available (N = 5), and language limitations (N = 18). An additional 33 studies missed quantitative data under the outcomes of interest and were therefore not considered. In conclusion, four RCTs were included in the present meta-analysis. The results of the literature search are shown in Fig. 1.

Risk of bias assessment

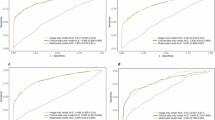

The Cochrane risk of bias tool (ROB2) was used to investigate the risk of bias in all studies included in the present meta-analysis. The randomisation process was predominantly of high quality using a random number generator. No baseline differences were found between study groups in any study. In two studies, there were concerns about deviations from the planned intervention because patients and investigators were not blinded after randomisation. The risk of bias from missing outcome data was noted in two studies, as the number of patients who dropped out during the study period differed between the comparison groups and was not compensated for. In terms of outcome measurement, only one study raised concerns, and the risk of bias in the selection of the reported outcome was uniformly low. Concluding, the risk of bias graph evidenced a predominantly low to moderate quality of the methodological assessment of the RCTs (Fig. 2).

Study characteristics and results of individual studies

Data from 197 TKAs were retrieved. 67% (132 of 197 patients) were women. The mean length of the follow-up was 7.0 ± 5.8 weeks. The mean age of the patients was 69.6 ± 2.7 years, and the mean BMI was 28.7 ± 0.9 kg/m2. The generalities and demographics of the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Baseline comparability

At baseline, between-group comparability was evidenced in the ratio of male:female, mean age, mean BMI, knee flexion, and VAS (Table 2).

Synthesis of results

No difference was found in flexion (P = 0.7) and VAS (P = 0.3). No difference was found in the circumference of the lower leg: tight (P = 0.8), knee (P = 0.4), calf (P = 0.4), and ankle (P = 0.3). The forest plots are reported in Fig. 3.

Discussion

According to the findings of the present meta-analysis, the current level I of evidence does not support the use of MLD in primary TKA.

Ebert et al.32 randomised 41 patients (50 knees) to receive MLD or to the control group. Patients who underwent MLD demonstrated significantly greater active knee flexion 4 days and 6 weeks after TKA32. However, no significant effects were found on passive knee flexion, lower limb circumference, or subjective scores32. In the RCT by Guney-Deniz et al.33, 45 female patients with unilateral TKA were assigned to MLD (n = 15) combined with exercises, kinesiotaping (n = 15) combined with exercises, or exercises in isolation (n = 15). MLD significantly reduced pain and thigh and calf oedema from the second to the fourth postoperative day, with greater efficacy compared to the control group33. These results were confirmed also 2 weeks postoperatively33. No difference was found in the range of motion33. At 6-week follow-up, no differences were observed between the groups in oedema, pain, motion, and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)33. Pichonnaz et al.34 randomly allocated 60 patients to receive five sessions of MLD in addition to the usual postoperative rehabilitation or to the control group. There was no significant difference between the two groups at 7 days and 3 months, except for passive knee flexion contracture at 3 months, which was lower and less frequent in the MLD group34. Pain levels significantly decreased after MLD treatments34. MLD was not effective in reducing oedema34. In another RCT on 99 patients, Tornatore et al.35 compared kinesiotaping combined with MDL vs. MDL or kinesiotaping in isolation. Combined kinesiotaping and MLD reduced pain and oedema more than any other treatment in isolation35. MLD in isolation was more effective in reducing oedema than kinesiotaping in isolation35. No differences were found in flexion among the groups35.

The present investigation did not identify clinical advantages of MLD in TKA. The duration and intensity of MLD sessions were variable among the included studies, which may have affected the validity of the results. The techniques and MLD protocols were not described in depth, which represents another important limitation, which may have impacted the reliability of the present results. Standardizing MLD protocols, that provide adequate descriptions of the technique would provide more consistent and comparable data for analysis in future research. Irrespective of these limitations, results from the present study are consistent with the current literature. The efficacy of MLD in musculoskeletal medicine is controversial42,43,44,45,46. After orthopaedic surgery, tissue swelling may be associated with a longer recovery and increased pain, limited mobility, reduced function, and interference with the wound healing process47,48. The most important limitation on the clinical efficacy of MLD is the limited evidence available in the current literature. Moreover, considering the lack of guidelines or recommendations, the use of MLD following TKA should be considered cautiously. MLD has been evaluated also in other areas, with similar conclusions49,50,51,52.

Additional limitations are evident. There was much variability between the included studies in sample size, duration of follow-up, intervention protocols, and outcome measures. Another major limitation of the present study is the lack of standardisation of MLD protocols and techniques in terms of session duration, intensity, and frequency, which could have led to potential variations in the efficacy of the intervention. Moreover, the surgical technique, exposure, and implants were not often described. Similarly, whether patients underwent patellar resurfacing or received cemented or press-fit implants was often biased, as was the use of the tourniquet or tranexamic acid. Given the lack of quantitative data, additional analyses were not possible. In the outcome assessment, the measures were limited to flexion, pain, and lower leg circumference. Other relevant outcomes, such as function, quality of life, and patient satisfaction PROMs, should be considered in future investigations. An additional implication of MLD is the evaluation of cost efficacy, as this procedure requires trained personnel. The method of MLD was not specified in detail in most studies. Being a non-invasive procedure, MLD deserves further research to provide more robust evidence in support of its efficacy in TKA. The risk of bias graph evidenced a predominantly low to moderate quality of the methodological assessment of the RCTs. In two studies, there were concerns about deviations from the planned intervention because patients and investigators were not blinded after randomisation. The risk of bias from missing outcome data was noted in two studies, as the number of patients who dropped out during the study period differed between the comparison groups and was not compensated for. In terms of outcome measurement, only one study raised concerns, and the risk of bias in the selection of the reported outcome was uniformly low. More precisely, in the study conducted by Ebert et al.32, all in-hospital clinical assessments were carried out by physiotherapists who were unaware of patient randomization. However, despite preventing the supervising physiotherapist from having contact with massage therapists and instructing patients to avoid discussing study information with their supervising physiotherapist, achieving complete blinding in a study of this nature proved to be difficult. In the study by Pichonnaz et al.34, the measurement of pain was performed by the treating physiotherapist immediately after the treatment. This aspect represents a lack of blinding that could have influenced the results (Supplementary Information).

Conclusion

According to the current level I evidence, MLD in primary TKA is not associated with an improvement in ROM, pain, and circumference of the lower leg. Additional high-quality investigations are strongly required to assess the efficacy of MLD in primary TKA.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available throughout the manuscript.

References

Hernandez-Hermoso, J. A. et al. Combined femoral and tibial component total knee arthroplasty device rotation measurement is reliable and predicts clinical outcome. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 24(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10195-023-00718-2 (2023).

Matassi, F., Pettinari, F., Frascona, F., Innocenti, M. & Civinini, R. Coronal alignment in total knee arthroplasty: A review. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 24(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10195-023-00702-w (2023).

Wang, L., Xu, Q., Chen, Y., Zhu, Z. & Cao, Y. Associations between weather conditions and osteoarthritis pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 55(1), 2196439. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2196439 (2023).

Cao, Z., Wu, Y., Li, Q., Li, Y. & Wu, J. A causal relationship between childhood obesity and risk of osteoarthritis: Results from a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. Ann. Med. 54(1), 1636–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2022.2085883 (2022).

Shavazipour, B., Afsar, B., Multanen, J., Miettinen, K. & Kujala, U. M. Interactive multiobjective optimization for finding the most preferred exercise therapy modality in knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Med. 54(1), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2021.2024876 (2022).

Wang, R. et al. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with haemophilic arthropathy is effective and safe according to the outcomes at a mid-term follow-up. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 23(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10195-022-00648-5 (2022).

Guney Yilmaz, G., Akel, B. S., Sevimli Saitoglu, Y. & Aki, E. Occupational self-perception level effects on the development of kinesiophobia in individuals with total knee arthroplasty. J. Orthop. 42, 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2023.07.020 (2023).

Abourisha, E. et al. Aspirin as a thromboprophylaxis agent after revision knee arthroplasty: A retrospective analysis. J. Orthop. 41, 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2023.05.006 (2023).

Gelderman, S. J., van Jonbergen, H. P., van Steenbergen, L., Landman, E. & Kleinlugtenbelt, Y. V. Patients undergoing revisions for total knee replacement malposition are younger and more often female: An analysis of data from the Dutch Arthroplasty register. J. Orthop. 40, 70–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2023.04.020 (2023).

Pavao, D. M. et al. Predictive and protective factors for allogenic blood transfusion in total knee arthroplasty. A retrospective cohort study. J. Orthop. 40, 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2023.04.015 (2023).

Tamashiro, K. K., Morikawa, L., Andrews, S. & Nakasone, C. K. Can single-stage bilateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty be safely performed in patients over 70? J. Orthop. 37, 41–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2023.02.005 (2023).

Migliorini, F. et al. Correction to: Better outcomes after minisubvastus approach for primary total knee arthroplasty: A Bayesian network metaanalysis. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 31(6), 1259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-021-03026-9 (2021).

Migliorini, F. et al. Gap balancing versus measured resection for primary total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis study. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-020-03478-4 (2020).

Migliorini, F., Eschweiler, J., Tingart, M. & Rath, B. Posterior-stabilized versus cruciate-retained implants for total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis of clinical trials. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 29(4), 937–946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-019-02370-1 (2019).

Migliorini, F. et al. Robotic-assisted total knee arthroplasty in clinical practice: Protocol for a randomised controlled trial. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18(1), 623. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-04101-z (2023).

Migliorini, F., Pintore, A., Cipollaro, L., Oliva, F. & Maffulli, N. Outpatient total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. Appl. Sci. 11(20), 9376. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11209376 (2021).

Migliorini, F., Tingart, M., Niewiera, M., Rath, B. & Eschweiler, J. Unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty for knee osteoarthritis. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 29(4), 947–955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-018-2358-9 (2019).

Su, W., Zhou, Y., Qiu, H. & Wu, H. The effects of preoperative rehabilitation on pain and functional outcome after total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17(1), 175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03066-9 (2022).

Castle, J. P. et al. Survey of blood flow restriction therapy for rehabilitation in Sports Medicine patients. J. Orthop. 38, 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2023.03.007 (2023).

Gildone, A., Punginelli, B., Manfredini, M., Artioli, A. & Faccini, R. A comparison of two rehabilitation protocols after total knee arthroplasty: Does flexion affect mobility and blood loss? J. Orthop. Traumatol. 8(1), 6–10 (2007).

Calvisi, V., Lupparelli, S. & Padua, R. Do bisphosphonates reduce early micromotion and Periprosthetic bone loss in total knee arthroplasty? A review of the evidence. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 7, 201–206 (2006).

Bistolfi, A. et al. Cemented fixed-bearing PFC total knee arthroplasty: Survival and failure analysis at 12–17 years. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 12(3), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10195-011-0142-2 (2011).

Mannani, M., Motififard, M., Farajzadegan, Z. & Nemati, A. Length of stay in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. J. Orthop. 32, 121–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2022.05.018 (2022).

Harrison, A. E. et al. Postoperative outcomes of total knee arthroplasty across varying levels of multimodal pain management protocol adherence. J. Orthop. 28, 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2021.10.005 (2021).

Guo, J., Hou, M., Shi, G., Bai, N. & Huo, M. iPACK block (local anesthetic infiltration of the interspace between the popliteal artery and the posterior knee capsule) added to the adductor canal blocks versus the adductor canal blocks in the pain management after total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17(1), 387. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03272-5 (2022).

Kang, J. et al. The efficacy of perioperative gabapentin for the treatment of postoperative pain following total knee and hip arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 15(1), 332. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-01849-6 (2020).

Klein, I., Tidhar, D. & Kalichman, L. Lymphatic treatments after orthopedic surgery or injury: A systematic review. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 24(4), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.06.034 (2020).

Majewski-Schrage, T. & Snyder, K. The effectiveness of manual lymphatic drainage in patients with orthopedic injuries. J. Sport Rehabil. 25(1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.2014-0222 (2016).

Oktas, B. & Vergili, O. The effect of intensive exercise program and kinesiotaping following total knee arthroplasty on functional recovery of patients. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 13(1), 233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-018-0924-9 (2018).

Morris, D., Jones, D., Ryan, H. & Ryan, C. G. The clinical effects of Kinesio(R) tex taping: A systematic review. Physiother. Theory Pract. 29(4), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.3109/09593985.2012.731675 (2013).

Mostafavifar, M., Wertz, J. & Borchers, J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of kinesio taping for musculoskeletal injury. Phys. Sports Med. 40(4), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.3810/psm.2012.11.1986 (2012).

Ebert, J. R., Joss, B., Jardine, B. & Wood, D. J. Randomized trial investigating the efficacy of manual lymphatic drainage to improve early outcome after total knee arthroplasty. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 94(11), 2103–2111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.06.009 (2013).

Guney-Deniz, H. et al. Manual lymphatic drainage and kinesio taping applications reduce early-stage lower extremity edema and pain following total knee arthroplasty. Physiother. Theory Pract. 39(8), 1582–1590. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2022.2044422 (2023).

Pichonnaz, C. et al. Effect of manual lymphatic drainage after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 97(5), 674–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.01.006 (2016).

Tornatore, L., De Luca, M. L., Ciccarello, M. & Benedetti, M. G. Effects of combining manual lymphatic drainage and Kinesiotaping on pain, edema, and range of motion in patients with total knee replacement: A randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 43(3), 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0000000000000417 (2020).

Howick, J. C. I. et al. The 2011 Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. https://www.cebmnet/indexaspx?o=5653 (2011).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 (2021).

Cumpston, M. et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: A new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, ED000142. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.ED000142 (2019).

Higgins, J. P. T. S. J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G. & Sterne, J. A. C. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3 (Updated February 2022) (eds Higgins, J. P. T. et al.) (Cochrane, 2022).

Sterne, J. A. C. et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366, l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898 (2019).

Higgins, J. P. T. T. J. et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2 (Cochrane, 2021).

Gutierrez-Espinoza, H. et al. Effectiveness of manual therapy in patients with distal radius fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Manual Manipul. Ther. 30(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669817.2021.1992090 (2022).

Vairo, G. L., Miller, S. J., McBrier, N. M. & Buckley, W. E. Systematic review of efficacy for manual lymphatic drainage techniques in sports medicine and rehabilitation: An evidence-based practice approach. J. Manual Manipul. Ther. 17(3), e80–e89. https://doi.org/10.1179/jmt.2009.17.3.80E (2009).

Singh, R., Rymer, B., Youssef, B. & Lim, J. The Morel-Lavallee lesion and its management: A review of the literature. J. Orthop. 15(4), 917–921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2018.08.032 (2018).

Dresing, K., Fischer, A. C., Lehmann, W., Saul, D. & Spering, C. Perioperative and posttraumatic anti-edematous decongestive device-based negative pressure treatment for anti-edematous swelling treatment of the lower extremity—A prospective quality study. Int. J. Burns Trauma 11(3), 145–155 (2021).

Rigoni, S., Tagliaro, L., Bau, D. & Scapin, M. Effectiveness of two rehabilitation treatments in the modulation of inflammation during the acute phase in patients with knee prostheses and assessment of the role of the diet in determining post-surgical inflammation. J. Orthop. 25, 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2021.05.016 (2021).

Akdeniz Leblebicier, M. et al. Does manual lymphatic drainage improve upper extremity functionality in female patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis? A randomized controlled study. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.14849 (2023).

Weber, M. et al. Postoperative swelling after elbow surgery: Influence of a negative pressure application in comparison to manual lymphatic drainage—A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-023-04954-3 (2023).

Algar-Ramirez, M., Ubeda-D’Ocasar, E. & Hervas-Perez, J. P. Efficacy of manual lymph drainage and myofascial therapy in patients with fibromyalgia: A systematic review. Schmerz 35(5), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00482-020-00520-7 (2021).

De Vrieze, T. et al. Manual lymphatic drainage with or without fluoroscopy guidance did not substantially improve the effect of decongestive lymphatic therapy in people with breast cancer-related lymphoedema (EFforT-BCRL trial): A multicentre randomised trial. J. Physiother. 68(2), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2022.03.010 (2022).

Liang, M. et al. Manual lymphatic drainage for lymphedema in patients after breast cancer surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 99(49), e23192. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000023192 (2020).

Schulze, N. B., Salemi, M. M., de Alencar, G. G., Moreira, M. C. & de Siqueira, G. R. Efficacy of manual therapy on pain, impact of disease, and quality of life in the treatment of fibromyalgia: A systematic review. Pain Phys. 23(5), 461–476 (2020).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.M.: literature search, conception and design, statistical analysis, drafting; N.M.: supervision, revision; F.A.B.: writing; L.S.: literature search, selection and data extraction, risk of bias assessment; R.G.: literature search, selection and data extraction; F.S.: writing; M.K.M.: supervision. All authors have agreed to the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Migliorini, F., Schäfer, L., Bertini, F.A. et al. Level I of evidence does not support manual lymphatic drainage for total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 13, 22024 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49291-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49291-y

This article is cited by

-

No significant short-term advantages of corticosteroids-augmented intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis

Die Orthopädie (2026)

-

Improved accuracy of functional alignment restoration with robotic-assisted total knee arthroplasty

Die Orthopädie (2025)

-

Intra-articular Hyaluronic Acid Injections May Be Beneficial in Patients with Less Advanced Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials

Sports Medicine (2025)

-

Massage for rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2024)

-

Demonstration of the effectiveness of complete decongestive treatment in secondary lymphedema developing after total knee arthroplasty

European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology (2024)