Abstract

Stress arousal reappraisal (SAR) and stress-is-enhancing (SIE) mindset interventions aim to promote a more adaptive stress response by educating individuals about the functionality of stress. As part of this framework, an adaptive stress response is coupled with improved performance on stressful tasks. The goal of this meta-analysis is to evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions on task performance. The literature search yielded 44 effect sizes, and a random-effects model with Knapp-Hartung adjustment was used to pool them. The results revealed an overall small significant improvement in task performance (d = 0.23, p < 0.001). The effect size was significantly larger for mixed interventions (i.e., SAR/SIE mindset instructions combined with additional content, k = 5, d = 0.45, p = 0.004) than SAR-only interventions (k = 33, d = 0.22, p < 0.001) and SIE mindset-only interventions (k = 6, d = 0.18, p = 0.22) and tended to be larger for public performance tasks than cognitive written tasks (k = 14, d = 0.34, p < 0.001 vs. k = 30, d = 0.20, p = 0.002). Although SAR and SIE mindset interventions are not “silver bullets”, they offer a promising cost-effective low-threshold approach to improve performance across various domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stress is a loyal companion that is omnipresent through all stages of an individual’s life. This complex state is appraised, experienced, and managed in different ways depending on a person’s characteristics and the situational context1. Hans Selye, the pioneer in stress research, defined stress as “the non-specific response of the body to any demand made upon it”2. According to Selye, experiencing stress can yield either positive (eustress) or negative (distress) outcomes. While both sides are present in most major stress theories, the positive aspects have received far less attention in research3,4,5. While prolonged and excessive stress can negatively impact physical and mental health (e.g.6,7,8), short term stress responses evolved to ensure survival and to allow thriving in most demanding situations6. The perspective that stress is essential for human functioning, growth, and performance, is not widely spread and for the most part, the term stress has become synonym with distress. This predominantly negative view can be problematic as it indirectly suggests that stress must be avoided or reduced9. However, stress is unavoidable in various domains of daily life. Situations that are of personal importance and require an individual to perform (e.g., school examinations, job interviews, sports competitions) will likely trigger stress9. Conventional stress management strategies aim at downregulating or ignoring stress altogether10. Yet, research suggests that the way an individual perceives stress can lead to differences in the stress response (e.g.11,12,13,14). Specifically, accepting and appraising stress as functional and helpful instead of harmful, might evoke a more adaptive stress response.

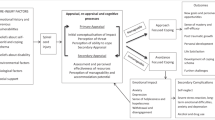

Stress arousal reappraisal (SAR) and stress-is-enhancing (SIE) mindset interventions have the same goal of promoting a more adaptive stress response by educating individuals about the functional aspects of stress15,16. They both aim to foster an individual’s agency in channeling and utilizing stress responses in a way that is beneficial for mastering stressors. However, there is a salient difference between these two approaches. Whereas SAR interventions function through situation specific appraisals of perceived task demands and coping resources, SIE mindset interventions frame stress as generally enhancing, independent of how a specific situation is appraised. Acknowledging these similarities and differences, authors have recently proposed integrative models9,17.

One line of research has been interested in studying the experiential (e.g., subjective affective experience) and physiological (e.g., cardiovascular activity) effects of SAR and SIE mindset interventions (e.g.18,19,20). A meta-analysis found a small positive effect of both interventions on the subjective stress response but no significant effect on the physiological response21. A second line of research has focused on investigating if SAR and SIE mindset interventions can improve performance outcomes (in, e.g., academic examinations13, public speaking11, sports14). The present study aims to analyze this research question meta-analytically.

Stress arousal reappraisal (SAR) interventions and task performance

SAR (often also called stress reappraisal or arousal reappraisal) refers to the cognitive reframing of the meaning of arousal experienced in the context of stressful situations or tasks22. SAR interventions are rooted in the biopsychosocial model of challenge and threat, which frames biological, psychological, and behavioral aspects of stress as interrelated patterns in the context of motivated performance situations (i.e., situations in which an active response is needed to achieve personally relevant goals). According to this model, adaptive cardiovascular and performance enhancing (challenge-oriented) stress responses are achieved when perceived personal resources outweigh perceived situational demands, whereas debilitative (threat-oriented) stress responses are caused by perceiving situational demands as exceeding personal resources23,24. SAR interventions advise individuals to reappraise the stress response itself as a resource to cope with the situational demands of the task at hand, thereby causing a shift towards challenge-oriented stress responses. More precisely, they convey the message that the body's response to stressors (i.e., stress arousal) can be functional and adaptive and thus invite individuals to think of their stress arousal as helpful rather than harmful for task performance17. For example, Jamieson and colleagues’25 SAR interventional material reads as follows: “People think that feeling anxious while taking a standardized test will make them do poorly on the test. However, recent research suggests that arousal doesn’t hurt performance on these tests and can even help performance… people who feel anxious during a test might actually do better. This means that you shouldn’t feel concerned if you do feel anxious while taking today’s GRE test. If you find yourself feeling anxious, simply remind yourself that your arousal could be helping you do well.” Revised versions of the SAR intervention were made more exhaustive26,27 by clarifying the functionality and evolutionary benefits of the body’s stress response (e.g., an increased heart rate is a sign that the body is being fueled with more oxygen, therefore preparing an individual to perform). A more in-depth analysis of the SAR intervention and the exact mechanism of the biopsychosocial model of challenge and threat can be found elsewhere (e.g.22).

To our knowledge, the first study that evaluated the effects of what we consider SAR on performance was conducted by Garcia in 198228. In this study, math-anxious students met with a therapist six times over the course of four weeks. During the meetings, students imagined themselves in a physiological aroused state and were instructed to envision the arousal as sign of the body releasing energy which should be utilized to manage the task ahead. After the training, participants in the SAR condition achieved significantly higher scores on a math exam than participants in the neutral control condition.

More recently, SAR attracted new interest as an intervention capable of improving task performance. Jamieson and colleagues showed that students administered with a SAR intervention consisting of a brief statement (see above) performed significantly better than controls on a math exam but not on a verbal exam25. Over the past decade, the effects of SAR interventions on task performance have been evaluated in different domains (academic examinations e.g.29,30,31, tasks in sports14,32, and verbal interactions e.g.11,33,34).The results appear rather inconsistent, with studies finding SAR interventions to have negative effects on reading span35 and math performance36, no effects on intelligence tests37 and quantitative reasoning38, but positive effects on golf putting14 and math performance13.

Stress-is-enhancing (SIE) mindset interventions and task performance

Stress mindset theory evolved from the concept of implicit theories39, which represent organizing principles that encompass specific beliefs, assumptions, and expectations about a human attribute or construct (e.g., intelligence, personality) and their malleability. A mindset can be described as a cognitive framework that selectively processes information gathered in the environment and can be explicitly altered40. Accordingly, stress mindsets refer to beliefs and assumptions that one associates with the nature of stress. Although authors differ to some extend in the conceptualization of stress mindset (e.g.39,41,42,43), a key distinction is between two opposing mindsets: an SIE mindset is represented by beliefs that stress can enhance performance, health, wellbeing, learning, and growth, whereas a stress-is-debilitating (SID) mindset comes with the assumption that stress has debilitating effects. According to stress mindset theory, a person’s mindset guides the anticipation and experience of a stressful event. An SID mindset motivates an individual to avoid or downregulate the stress response and thus its “harmful” consequences. An SIE mindset encourages individuals to accept and utilize the enhancing effects that stress can provide39,44. SIE mindset interventions promote the idea that stress mindsets are not fixed and foster positive associations about stress in an attempt to optimize stress responses39,44. The goal is for individuals to be able to consciously adopt an SIE mindset when confronted with demanding situations. A more detailed overview of stress mindset theory and its mechanisms is available elsewhere15,17.

In an early series of studies, Crum and colleagues provided evidence for correlations between stress mindsets and physiological and behavioral stress responses39. Moreover, participants who were shown three 3-min videos that either promoted the enhancing or debilitating effects of stress on performance, health, wellbeing, growth, and learning exhibited corresponding changes in their beliefs about stress, self-reported work performance, and wellbeing (i.e., SIE mindset increased performance and wellbeing)39. Following this initial effort, a shorter 3-min version focused on cognitive performance12 and an extensive (60–120 min) version of the SIE mindset intervention were introduced45. In general, the different adaptations of the SIE mindset intervention were consistent in promoting a more positive stress mindset, with the extensive version evoking the most sustainable changes in stress mindset45. Despite changes in people’s stress mindset have been consistently reported, the effects of the stress mindset interventions on performance have not been as clear. One study found positive effects on articulation rate of tongue twisters46, while performance improvements in other studies were dependent on factors such as genotype (Stroop-task47) or feedback condition (alternative use task12). Further, performance enhancing effects in academics were only achieved by combining SIE mindset interventions with other content, such as imagery exercise48 or growth mindset about abilities/intelligence49. The intervention failed to improve academic grades in a study with disadvantaged students50.

Present review

We bring forward two concerns that might prevent optimal use and development of the SAR and SIE mindset interventions. First, research has reported inconsistent results about the effects of these interventions on performance outcomes. This makes it difficult to predict their future effectiveness when planning an intervention. It might also be a reason why the interventions went through multiple iterations and combinations with other elements, which leads to the second concern. The studies about both interventions possess a high degree of heterogeneity in terms of, e.g., intervention content and performance task. These differences introduce additional difficulties for researchers and educators to make informed decisions. We conducted this meta-analysis to address the following research questions: (1) How effective are SAR and SIE mindset interventions in improving task performance? (Overall effect) (2) Does the effectiveness of the interventions depend on specific studies’ characteristics (type of intervention, type of control group, type of task, reflection exercises, gender ratio).

Methods

The current meta-analysis is based on the PRISMA 2020 checklist (Supplementary Table S1) and preregistered on OSF Registries: https://osf.io/45w6h.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were derived from the PICOS51 framework. We included (1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a between-subjects design (2) in English, German, French, Italian, or Spanish, in which (3) either an SAR or SIE mindset intervention was applied (4) to target an active stress-inducing task, (5) for which performance was objectively assessed or rated in a standardized way, and (6) was compared to a neutral or active (stress related) control condition. We excluded (1) studies not meeting all inclusion criteria, (2) review articles, (3) duplicate articles or overlapping data, and (4) studies from which data could not be reliably extracted and for which we did not receive the necessary information from the authors upon request. The health of the participants was not a criterion (i.e., studies with both clinical and non-clinical populations were accepted).

Study selection

Standardized search

To formulate a suitable search string for the databases, we initially conducted a forward search on articles that are omnipresent in the SAR and stress mindset literature. After identifying 20 relevant articles, we analyzed the vocabulary that was used to describe the two interventions. We then combined related terms for stress (i.e., arousal, anxiety) and reappraisal (i.e., reframing, reinterpretation) as well as stress mindset to a single search string. By adding a proximity parameter, irrelevant articles were filtered out (e.g., stress and reappraisal could only be separated by a maximum of two words). Articles had to include respective terms in either the title, abstract, or keywords. To minimize the risk of missing out on potentially relevant articles, we chose a sensitive approach by not including performance (outcome) in the search string. Database specific strings can be found in the Supplementary Table S2.

The standardized article search was conducted on December 12, 2022. We searched the following databases to cover various research fields, peer-reviewed articles, dissertations, and theses: Psycinfo, Scopus, Web of Science, MEDLINE, ERIC, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, and Cochrane.

The two authors independently assessed the articles based on the eligibility criteria. Initially, both authors screened the title and abstract of all articles and decided for which articles the full text should be retrieved. When no consensus could be reached between the reviewers, an inclusive approach was chosen.

Exploratory search

After the electronic database search, we further conducted an exploratory backward and forward reference search based on the most cited and recent articles and contacted authors who have published relevant articles and asked them for unpublished literature.

Data collection process

A data extraction sheet was pilot tested on 10 randomly selected studies. The purpose of the extraction sheet was to collect necessary statistics for effect size calculation (e.g., means, SD/SE, group size) or parameters that could be transformed into the desired effect size (e.g., F-values from univariate analyses, p-values). When effect sizes could not be reliably derived because of missing data, the authors of the articles were contacted by email. If the authors did not reply within two months, a second attempt was made to retrieve the necessary data.

Another goal was to code study characteristics for subgroup analysis, which were further refined during the data collection process. Therefore, we extracted information regarding study design, content of the intervention and control groups, type of outcome, and participant specifics (e.g., gender). Although the overall quality of the studies was high because we only included RCTs, we additionally assessed the quality of each study on four items (see Supplementary Note 1). The items were based on the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials for Social and Psychological Interventions (CONSORT-SPI 201852) and aspects that were not already given by RCTs (e.g., randomization). Each study received a quality score ranging from 0 to 4 (see Supplementary Table S3 for the individual ratings). During the data collection process, all outcome data was extracted in duplicate by the two authors. For the coding of additional study characteristics, one reviewer was tasked with extracting the data from the studies, while the second reviewer double-checked the extracted characteristics. There was no disagreement between reviewers. Table 1 summarizes the studies’ core characteristics.

Effect size calculation

To evaluate how SAR and SIE mindset interventions affect performance compared to control conditions, we used Cohen’s d64 for the main analysis. Because the studies were performed in various domains (e.g., academic, sports), the study designs and performance outcomes were highly heterogeneous. Consequently, we assumed a random-effects model for the analysis. Since the performance outcome in all studies was continuous, we applied restricted maximum likelihood estimator to evaluate the variance of the heterogeneity τ2 65. Further, the Knapp-Hartung adjustment was used in the estimation of the confidence interval of the pooled effect size to minimize the probability of a false positive result66. We used a generic inverse variance approach to weigh the individual effect sizes. Some of the effect sizes had to be reversed since smaller outcome values indicated better performances14,32,46,47,59. A forest plot was used to illustrate the pooled effect size and individual effect sizes. For the main analysis, R (version 4.3.367) package meta68 was used.

Whenever possible, we extracted the raw data including mean, SD, and sample size (n) of the intervention and control group to calculate the effect size and SE of each study. In one study50, the SE had to be extracted from the displayed barplot. For studies where the raw data was missing, we converted the available statistics (e.g., F-values from univariate analysis, p-values) into the desired effect size and SE. If the group sizes were missing and not provided by the authors upon request, we assumed equal group sizes. When performance was measured multiple times (e.g., baseline, immediately after intervention, days later), we included and averaged all outcomes after the intervention. We disregarded pre-test data and change scores for the analysis because this data was not consistently reported, and mixing standardized outcomes for change scores and single measures was not sensible69. Possible baseline differences should have occurred randomly and therefore balanced out across studies. If two or more performance outcomes were reported, and none was declared or could be identified as the main outcome, we aggregated effect sizes and SEs for all outcomes. We additionally conducted a three-level meta-analysis and a meta-analysis with robust variance estimation and sensitivity analysis for the assumed correlation ρ (using R-package metafor70 and clubSandwich71) to account for dependencies caused by effect sizes from the same study (see Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). All three approaches led to identical results. For simplicity’s sake, we chose to report aggregated effect sizes. When studies reported independent results for multiple subgroups (e.g., first year students, upper year students29), we treated the result for each subgroup as an individual study. For studies that compared SAR or SIE mindset interventions to more than one other condition, we included all relevant comparisons and reported them as individual studies. Relevant comparisons were either neutral control conditions unrelated to stress (e.g., no information, summary about brain) or active control conditions that discussed stress but did not portray it as performance enhancing (e.g., SID mindset, ignore stress). If this meant that the same group of participants was used in more than one comparison (e.g., SAR vs. neutral control, SAR vs. active control), the respective group size was adjusted in the calculation of the effect size and SE (e.g., halved for two comparisons). Other types of experimental/control conditions were rare and were not considered in our analyses. For example, Ganley et al.38 tested five groups: SAR, “excited”, expressive writing, “look ahead”, and a neutral control group. We only included the comparison between the SAR group and the neutral control group. No study was excluded in this process.

Publication bias assessment

A visual inspection of funnel plots, the trim and fill method72 (R-package meta68), and Egger’s test73 (R-package tidyverse74) were conducted to evaluate possible asymmetry in effect sizes. A p-curve analysis (R-package dmetar75) additionally indicated whether an evidential value was present or if the data emerged from selective reporting or p-hacking.

Subgroup analysis

As per pre-registration, we sought to analyze the moderating effects of 11 factors. Due to missing data, lack of variance, or the impossibility to create meaningful subgroups, the following factors could not be considered: delivery of intervention, timing of intervention, age of participants, setting, population, and expertise on task. The following aspects were considered for subgroup analyses.

Type of intervention

A first central distinction was made between SAR and SIE mindset interventions. A third category included all “mixed” interventions, which could include additional elements (e.g., SAR and imagery exercises28,48).

Control group

We made a distinction between neutral control groups that were unrelated to stress, and active control groups that altered the perception of stress (e.g., SID mindset, ignore stress).

Type of task

Two types of tasks were defined to group the individual studies: cognitive written tasks and public performance tasks. Cognitive written tasks included academic examinations and exercises (e.g.25,31,57), intelligence tests37, Stroop tasks47, alternative uses tasks (creativity)12 and working memory tasks61. Importantly, participants working alone on these tasks were not directly evaluated or judged by others. Public performance tasks were defined as tasks during which participants performed in front of an audience or interacted verbally with another person. These included the Trier Social Stress Test53,55,59, salary negotiations11, tongue twisters46, business pitches33,34, a golf putting task14, and a dart throwing task32. Social evaluation, which is a key element of public performance tasks, is a major stress factor76. Therefore, it is important to consider possible moderating effects caused by the nature of the task.

Reflection exercises

Reflection exercises instructed participants to answer questions, summarize the core information of SAR/SIE mindset interventions, reframe past stressful experiences, or envision how stress can be helpful in future scenarios (e.g., “In your own words please briefly describe how this information can help you perform well on your exam today”27). These reflection exercises had the goal to further help the participants internalize the idea that stress/arousal can enhance performance. Therefore, we differentiated between studies that included reflection exercises and those that did not.

Gender ratio

Male and female participants might be differently receptive to the two interventions. Not only do men and women experience stress differently but they also show different coping patterns77,78. There is evidence that gender modulates the effectiveness of different types of emotion regulation instructions and specifically SAR instructions on psychophysiological and performance outcomes58,79. Thus, we tested gender ratio as a potential moderator.

Results

Study selection

The standardized literature search yielded 2035 results, of which 1085 remained after removing duplicates. The agreement between reviewers on title and abstract screening was on a moderate level with a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.52. Articles were only excluded if both raters agreed on exclusion. This resulted in the inclusion of 117 articles, for which 112 full texts could be retrieved and reviewed in a second step. Three of the missing articles were study registrations for which the full text was not published yet, and two articles could not be accessed and were not provided by the authors upon request. Five articles were excluded due to insufficient statistics80,81,82,83,84. The exploratory backward and forward reference search provided another 23 full texts that were included for screening. Of the 135 full texts analyzed by the two reviewers, 33 were included in the meta-analysis. Lastly, 13 researchers were contacted for additional unpublished data but did not provide any. The individual steps of the study selection procedure are illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

In the end, 35 studies (33 articles) provided 44 effect sizes of which 35 were from peer reviewed publications and 9 from non-peer reviewed dissertations and theses (see Supplementary Note 2 for effect size aggregation). A total of N = 5638 participants were included in this meta-analysis of which 65.1% were female (weighted mean). None of the studies investigated a clinical population. The weighted mean age of the participants was 22.6 years. The quality of the studies ranged from 1 to 4 points, with a mean of M = 3.26 (SD = 0.79). Further study characteristics are reported in the subgroup analysis and in Table 1.

Overall effect

The pooled effect size of d = 0.23, 95% CI [0.14, 0.33], p < 0.001, indicated a small significant effect of the interventions on performance outcomes. Significant heterogeneity was indicated by a τ2 = 0.04, 95% CI [0.01, 0.10] and was estimated at a moderate level by an I2 = 52.6%, 95% CI [33.2%, 66.4%]. The prediction interval [− 0.18, 0.65] suggested that future studies might find small negative effects to moderate positive effects. The individual and pooled effect sizes are displayed in the forest plot (Fig. 2).

Subgroup analysis

Type of intervention

Most studies investigated SAR interventions (k = 33). Six studies evaluated SIE mindset interventions, and five studies evaluated SAR or SIE mindset interventions that were supported by additional content (mixed interventions). The effect sizes of the three subgroups were significantly different from one another (Q(2) = 7.08, p = 0.029). Mixed interventions achieved the largest effect (d = 0.45, 95% CI [0.24, 0.66], p = 0.004), followed by SAR interventions (d = 0.22, 95% CI [0.11, 0.32], p < 0.001) and SIE mindset interventions (d = 0.18, 95% CI [− 0.15, 0.51], p = 0.22). Heterogeneity remained on a moderate level within the subgroups for SAR interventions (I2 = 56.8%) and SIE mindset interventions (I2 = 50.1%). The mixed interventions group yielded no between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%).

Control group

Most studies included a neutral control condition (k = 30), whereas the remaining ones used an active stress related control condition (k = 14). The between group difference was not significant (Q(1) = 1.47, p = 0.23). Notably, a small significant (d = 0.20, 95% CI [0.09, 0.31], p = 0.001) effect size resulted from studies using a neutral control condition. The effect size was larger for studies using an active control condition (d = 0.31, 95% CI [0.14, 0.48], p = 0.001). Heterogeneity within the subgroups was similar to the overall heterogeneity (neutral, I2 = 50.9% vs. active, I2 = 48.2%).

Type of task

About two thirds of the tasks were cognitive written tasks (k = 30), and one third were public performance tasks (k = 14). The results of the subgroup analysis suggest a trending difference between these two task types (Q(1) = 3.43, p = 0.064). The effect size was smaller for cognitive written tasks than public performance tasks (d = 0.20, 95% CI [0.08, 0.31], p = 0.002 vs. d = 0.34, 95% CI [0.22, 0.46], p < 0.001). For cognitive written tasks, the heterogeneity was at a moderate level (I2 = 62.0%), whereas there was no between-study heterogeneity for public performance tasks (I2 = 0.0%).

Reflection exercises

Twenty-six studies instructed participants to reflect on the information that was presented about stress/arousal, whereas 17 did not include this element. One study alternated between self-reflection and no self-reflection and was therefore removed from this analysis62. There were no significant differences in the effect sizes of these two approaches (Q(1) = 0.07, p = 0.80; reflection exercises d = 0.23, 95% CI [0.11, 0.34], p < 0.001; no reflection exercises d = 0.25, 95% CI [0.07, 0.44], p = 0.011). Between-study heterogeneity was slightly lower for tasks with (I2 = 51.2%) than without (I2 = 59.1%) reflection exercises.

Gender ratio

Gender ratio had no significant impact on the effect size (β = 0.007, 95% CI [0.10, 0.12], p = 0.89) and did not explain any between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 55.9%). For this analysis, a square root transformation of gender ratio was used to achieve a normal distribution.

Quality/risk of bias

The meta-regression suggested that quality was not a significant predictor of the effect size (β = − 0.057, 95% CI [− 0.18, 0.07], p = 0.38). Accordingly, the unexplained heterogeneity in effect sizes remained similar at I2 = 54.8%.

Publication bias

Several approaches were applied to investigate the possibility of publication bias. First, by inspecting the funnel plot (Fig. 3a) an asymmetry in effect sizes became visible. Smaller studies (i.e., higher SEs) had a disproportionate amount of effect sizes larger than the pooled effect size. The trim and fill method72 suggested that 11 studies with a smaller effect size than the pooled effect were missing (indicated by white dots in Fig. 3b). After adding the missing studies to the analysis, the pooled effect size decreased to d = 0.14 (95% CI [0.04, 0.24]), yet remained significant (p = 0.007). A significant Egger’s test further endorsed the assumption of asymmetry in the effect sizes (β0 = 1.09, 95% CI [0.07, 2.11], t = 2.10, p = 0.042).

Finally, we utilized p-curve method to analyze the distribution of p-values85,86. As shown in Fig. 4, there was no indication for the absence of evidential value because both tests for flatness were not significant (pFull = 0.47, pHalf = 1). However, the p-curve neither supported the presence of an evidential value because only one test for right-skewness was below 0.1 (pFull = 0.005, pHalf = 0.20).

Discussion

Overall effect of the interventions on task performance

In this meta-analysis, we evaluated the effectiveness of SAR and SIE mindset interventions on performance outcomes. We summarized the results of 44 effect sizes retrieved from 35 studies conducted in varying domains, covering cognitive written (e.g., academic exams) and public performance tasks (i.e., performing in front of an audience). The pooled effect size revealed a small positive effect of the interventions on task performance. The differences in studies’ characteristics came with a moderate degree of between-study heterogeneity. We tried to resolve this heterogeneity by conducting subgroup analyses.

Moderating effects of studies’ characteristics

The type of intervention was the only factor that was found to significantly moderate the effect of the interventions. Interventions that complemented SAR or SIE mindset instructions with additional content (categorized as mixed interventions) achieved the largest effect size (d = 0.45). The mixed interventions group itself contained varying elements. An exact mechanism can therefore not be specified. However, as argued by Keech and colleagues48, the supportive elements may facilitate proactive coping behavior in general, possibly because the responsible neural networks are stimulated more thoroughly and readily accessible in stressful situations where cognitive capacities are limited87. However, compared to SAR-only and SIE mindset-only interventions, mixed interventions cannot be interpreted as easily due to possible confounding effects. While most recent research is already tending towards mixed approaches (e.g.48,49,59,88), these are not yet clearly defined and still offer possibilities to explore and experiment with.

Both SAR interventions and SIE mindset interventions produced a small increase in task performance (d = 0.22 and d = 0.18, respectively), with only the former type of intervention being statistically significant. In terms of effect size, the two interventions do no differ significantly, however, the small number of studies on SIE mindset interventions (k = 6) leads to a large estimate uncertainty which makes it difficult to interpret the results. Research comparing SAR and SIE mindset interventions is necessary to determine if and under what conditions these two approaches differ in their effectiveness on task performance.

The subgroup analysis also revealed a trend suggesting that SAR and SIE mindset interventions are more beneficial for public performance tasks than for cognitive written tasks. Social evaluation, which characterizes public performance tasks, induces particularly high physiological stress as indexed by cortisol level76. A possible explanation for this task related difference is that individuals in the control groups were better at coping with the lower stress level of cognitive written tasks than with the higher stress level of public performance tasks. However, there is also research indicating that reappraisal of high stress levels is difficult, and other strategies such as distraction are preferred89,90. Another aspect that might play a role in explaining the observed task related difference is the higher physical/bodily involvement in public performance tasks than in cognitive written tasks. One could speculate that the bodily signs of arousal are more relevant in public performance tasks and, thus, reframing them as helpful may be more meaningful and useful for performance enhancement.

The type of control condition (neutral vs. active) was not a significant modulator of the effect size, although the estimated effect size for the comparison with neutral control conditions was smaller than for the comparison with active control conditions (d = 0.20 vs. d = 0.31). This small difference in effect size appears plausible given that the active control conditions mostly tended to induce a threat state or SID mindset, which are supposed to be detrimental for performance outcomes (e.g.58,75). It is essential that the interventions yielded a significant effect when compared to a neutral control condition, as this isolates the positive effect of the SAR and SIE mindset interventions on task performance.

The addition of reflection exercises to the interventions offers two functions. First, it should help participants endorse the messages of the interventions and second, it provides an easy way to evaluate if participants paid attention to the presented information27. While these exercises fulfill the latter goal, the present meta-analysis suggests that they are redundant when it comes to improving task performance.

While one study found significant gender differences in the effect of a SAR intervention on task performance58, the gender effect does not appear when considering all published studies. Hangen and colleagues58 attributed the observed gender effect in their study to the unique competitive environment of the math task.

Finally, the quality of the studies was on average high and did not significantly moderate the effect of the interventions.

Publication bias

Concerns regarding publication bias must be addressed since smaller studies resulted in proportionally larger effect sizes. The result remained significant after applying the trim and fill method to compensate for possibly missing studies, still, the drop in effect size from d = 0.23 to d = 0.14 is worth noting. However, the p-curve analysis could neither support the presence nor absence of an evidential value. This indicates that more evidence is necessary to confirm a true effect.

Limitations and strengths

Several limitations should be mentioned to put the current findings into perspective. First, most of the studies investigated rather short-term effects. Thus, it remains unclear if the interventions potentially have long lasting effects on task performance. Nevertheless, studies that investigated long-term effects demonstrated positive lasting effects for several months (e.g.13,25,27,29,48,49,62 but see50). What remains unclear however is if these effects are also transferable to unrelated situations (e.g., from academics to sports). More research investigating the duration and transferability of the performance effects would be a valuable addition. On top of this, we were unable to weigh in the time that had passed between intervention and task, since it was often not possible to accurately identify this information.

Another concern is that most studies did not include baseline performance measures. Therefore, we had to focus on between group comparisons, and possible baseline differences could not directly be accounted for. By including 35 studies in the meta-analysis, random baseline differences should balance each other out. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that in at least one case32, the meta-analysis yielded a significant effect size, although the study reported a nonsignificant effect when controlling for the baseline performance in the analysis. We conclude that there is a need for pre-post longitudinal studies testing changes over time in performance outcomes following SAR and SIE mindset interventions.

Further, the positive effects of SAR and SIE mindset interventions on performance must be treated with caution since the performance outcome was not one single standardized measure. Although the subgroup analysis about the effect of the type of task combined tasks with similar characteristics and therefore provided some additional insights, the studies belonging to the same group were still heterogeneous. On the positive side, this diversity in the type of task illustrates that the effects of the interventions are not specific to a single task but rather universally applicable.

Lastly, the subgroup analysis included comparisons of subgroups that were unbalanced or small in terms of number of studies. In particular, 33 studies examined SAR interventions but only 6 studies SIE mindset interventions. Therefore, more studies are needed for a well-grounded estimation of the effect size for SIE mindset interventions. In the end, we were unable to explain between-study heterogeneity completely with the conducted subgroup analysis. Because the studies within subgroups were inconsistent (heterogeneity did not get resolved), it is difficult to draw nuanced conclusions.

A strength of the current meta-analysis is the selection of studies. We only included RCTs, which meant that the quality of the studies was largely high. We further chose a sensitive literature search approach, conducted a forward and backward search, and contacted many authors. By doing so, we retrieved gray literature and included a substantial number of dissertations to provide a comprehensive picture of the literature on the performance effects of SAR and SIE mindset interventions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this meta-analysis has shown that SAR and SIE mindset interventions are performance-enhancing across varying domains. Therefore, these interventions can also be considered promising for novel tasks that have not yet been researched. Because these interventions are self-administered, brief, low-threshold, and low-cost, they have the potential to be disseminated to many people, including those facing barriers. However, it must be noted that the overall effect size is small, and therefore these interventions should not be perceived as “silver bullets” for improving task performance. The interventions have proven especially effective for public performance tasks and when their content was supported by additional elements. Investigating the type of additional information that best complements SAR and SIE mindset interventions and the exact mechanism of action of these mixed approaches are important avenues for future research.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the tables and figures of this article. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the OSF repository, https://osf.io/z37d8/.

References

Gunnar, M. & Quevedo, K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annu. Review Psychol. 58, 145–173. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605 (2006).

Selye, H. Stress without distress. In Psychopathology of Human Adaptation (ed. Serban, G.) 137–146 (Springer, 1976).

Epel, E. S. et al. More than a feeling: A unified view of stress measurement for population science. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 49, 146–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.03.001 (2018).

Lazarus, R. S. & Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping (Springer, 1984).

Mendes, W. B. & Park, J. in Advances in motivation science, Vol. 1 (ed. Elliot, A. J.) 233–270 (Elsevier Academic Press, 2014).

Dhabhar, F. S. Effects of stress on immune function: The good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunol. Res. 58, 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-014-8517-0 (2014).

Marin, M.-F. et al. Chronic stress, cognitive functioning and mental health. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 96, 583–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2011.02.016 (2011).

Steptoe, A. & Kivimäki, M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 9, 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2012.45 (2012).

Crum, A. J., Jamieson, J. P. & Akinola, M. Optimizing stress: An integrated intervention for regulating stress responses. Emotion 20, 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000670 (2020).

Brooks, A. W. Get excited: Reappraising pre-performance anxiety as excitement. J. Exp. Psychol.-Gen. 143, 1144–1158. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035325 (2014).

Akinola, M., Fridman, I., Mor, S., Morris, M. W. & Crum, A. J. Adaptive appraisals of anxiety moderate the association between cortisol reactivity and performance in salary negotiations. PLOS ONE 11, e0167977. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167977 (2016).

Crum, A. J., Akinola, M., Martin, A. & Fath, S. The role of stress mindset in shaping cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses to challenging and threatening stress. Anxiety Stress Coping 30, 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2016.1275585 (2017).

Jamieson, J. P., Black, A. E., Pelaia, L. E. & Gravelding, H. Reappraising stress arousal improves affective, neuroendocrine, and academic performance outcomes in community college classrooms. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 151, 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000893 (2022).

Moore, L. J., Vine, S. J., Wilson, M. R. & Freeman, P. Reappraising threat: How to optimize performance under pressure. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 37, 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2014-0186 (2015).

Crum, A. J., Handley-Miner, I. J. & Smith, E. N. The stress-mindset intervention. In Handbook of Wise Interventions: How Social Psychology Can Help People Change (eds Walton, G. M. & Crum, A. J.) 217–238 (Guilford Press, 2021).

Jamieson, J. P. & Hangen, E. J. Stress reappraisal interventions: Improving acute stress responses in motivated performance contexts. In Handbook of Wise Interventions: How Social Psychology Can Help People Change (eds Walton, G. M. & Crum, A. J.) 239–258 (Guilford Press, 2021).

Jamieson, J. P., Crum, A. J., Goyer, J. P., Marotta, M. E. & Akinola, M. Optimizing stress responses with reappraisal and mindset interventions: An integrated model. Anxiety Stress Coping 31, 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2018.1442615 (2018).

Gross, J. J. Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J. Pers. Social Psychol. 74, 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.224 (1998).

Jamieson, J. P., Nock, M. K. & Mendes, W. B. Changing the conceptualization of stress in social anxiety disorder: Affective and physiological consequences. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 1, 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613482119 (2013).

Liu, J. J. W., Vickers, K., Reed, M. & Hadad, M. Re-conceptualizing stress: Shifting views on the consequences of stress and its effects on stress reactivity. Plos One 12, e0173188. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173188 (2017).

Liu, J. J. W., Ein, N., Gervasio, J. & Vickers, K. The efficacy of stress reappraisal interventions on stress responsivity: A meta-analysis and systematic review of existing evidence. Plos One 14, e0212854. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212854 (2019).

Jamieson, J. P., Hangen, E. J., Lee, H. Y. & Yeager, D. S. Capitalizing on appraisal processes to improve affective responses to social stress. Emot. Rev. 10, 30–39 (2018).

Blascovich, J. Challenge and threat. In Handbook of Approach and Avoidance Motivation (ed. Elliot, A. J.) 431–445 (Routledge, 2008).

Seery, M. D. Challenge or threat? Cardiovascular indexes of resilience and vulnerability to potential stress in humans. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35, 1603–1610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.03.003 (2011).

Jamieson, J. P., Mendes, W. B., Blackstock, E. & Schmader, T. Turning the knots in your stomach into bows: Reappraising arousal improves performance on the GRE. J. Exp. Social Psychol. 46, 208–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.08.015 (2010).

Jamieson, J. P., Nock, M. K. & Mendes, W. B. Mind over matter: Reappraising arousal improves cardiovascular and cognitive Responses to stress. J. Exp. Psychol.-Gen. 141, 417–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025719 (2012).

Jamieson, J. P., Peters, B. J., Greenwood, E. J. & Altose, A. J. Reappraising stress arousal improves performance and reduces evaluation anxiety in classroom exam situations. Social Psychol. Pers. Sci. 7, 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550616644656 (2016).

Garcia, L. The Treatment of Mathophobia by Means of Reinterpretation of Physiological Arousal as a Function of the Level of Perceived Arousal (Fordham University, 1982).

Brady, S. T., Hard, B. M. & Gross, J. J. Reappraising test anxiety increases academic performance of first-year college students. J. Educ. Psychol. 110, 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000219 (2018).

John-Henderson, N. A., Rheinschmidt, M. L. & Mendoza-Denton, R. Cytokine responses and math performance: The role of stereotype threat and anxiety reappraisals. J. Exp. Social Psychol. 56, 203–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.10.002 (2015).

Rozek, C. S., Ramirez, G., Fine, R. D. & Beilock, S. L. Reducing socioeconomic disparities in the STEM pipeline through student emotion regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1553–1558. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1808589116 (2019).

Sammy, N. et al. The effects of arousal reappraisal on stress responses, performance and attention. Anxiety Stress Coping 30, 619–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2017.1330952 (2017).

Oveis, C., Gu, Y., Ocampo, J. M., Hangen, E. J. & Jamieson, J. P. Emotion regulation contagion: Stress reappraisal promotes challenge responses in teammates. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 149, 2187–2205. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000757 (2020).

Zhu, L. Y. Linking Anxiety to Passion: Emotion Regulation and Entrepreneurs’ Pitch Performance (University of California, 2022).

Johns, M., Inzlicht, M. & Schmader, T. Stereotype threat and executive resource depletion: Examining the influence of emotion regulation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 137, 691–705. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013834 (2008).

Jacobs, S. E. Anxiety and Test Performance: An Emotion Regulation Perspective (Stanford University, 2013).

Ott, M. K. Testangst und deren Zusammenhang mit Testleistung: Effekte von Messzeitpunkt, Instruktion und funktionaler Bewertung der Angst (Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen, 2017).

Ganley, C. M., Conlon, R. A., McGraw, A. L., Barroso, C. & Geer, E. A. The effect of brief anxiety interventions on reported anxiety and math test performance. J. Numer. Cogn. 7, 4–19. https://doi.org/10.5964/jnc.6065 (2021).

Crum, A. J., Salovey, P. & Achor, S. Rethinking stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress response. J. Pers. Social Psychol. 104, 716–733. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031201 (2013).

Bernecker, K. & Job, V. Mindset theory. In Social Psychology in Action (eds Sassenberg, K. & Vliek, M. L. W.) 179–191 (Springer, 2019).

Keech, J. J., Cole, K. L., Hagger, M. S. & Hamilton, K. The association between stress mindset and physical and psychological wellbeing: Testing a stress beliefs model in police officers. Psychol. Health 35, 1306–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2020.1743841 (2020).

Kilby, C. J., Sherman, K. A. & Wuthrich, V. M. Believing is seeing: Development and validation of the STRESS (Subjective Thoughts REgarding Stress Scale) for measuring stress beliefs. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 190, 111535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111535 (2022).

Laferton, J. A. C., Stenzel, N. M. & Fischer, S. The Beliefs About Stress Scale (BASS): Development, reliability, and validity. Int. J. Stress Manag. 25, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000047 (2016).

Dweck, C. S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success (Random House, 2006).

Crum, A. J. et al. Evaluation of the “rethink stress” mindset intervention: A metacognitive approach to changing mindsets. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 152, 2603–2622. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001396 (2023).

Baynard-Montague, J. & James, L. E. A stress mindset manipulation can affect speakers’ articulation rate. Anxiety Stress Coping 36, 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2023.2179621 (2023).

Crum, A. J., Akinola, M., Turnwald, B. P., Kaptchuk, T. J. & Hall, K. T. Catechol-O-Methyltransferase moderates effect of stress mindset on affect and cognition. PLOS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195883 (2018).

Keech, J. J., Hagger, M. S. & Hamilton, K. Changing stress mindsets with a novel imagery intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Emotion 21, 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000678 (2021).

Yeager, D. S. et al. A synergistic mindsets intervention protects adolescents from stress. Nature 607, 512–520. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04907-7 (2022).

Goyer, J. P., Akinola, M., Grunberg, R. & Crum, A. J. Thriving under pressure: The effects of stress-related wise interventions on affect, sleep, and exam performance for college students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Emotion 8, 1755–1772. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001026 (2022).

O’Connor, D., Green, S. & Higgins, J. P. T. Defining the review question and developing criteria for including studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (eds Higgins, J. P. T. & Green, S.) 81–94 (Wiley, 2008).

Grant, S. et al. CONSORT-SPI 2018 explanation and elaboration: Guidance for reporting social and psychological intervention trials. Trials 19, 406. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2735-z (2018).

Beltzer, M. L., Nock, M. K., Peters, B. J. & Jamieson, J. P. Rethinking butterflies: The affective, physiological, and performance effects of reappraising arousal during social evaluation. Emotion 14, 761–768. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036326 (2014).

Chalmers, W. Arousal Reappraisal and Interoceptive Awareness: How Awareness of Bodily Changes Facilitates Heightened Performance and Ability to Reappraise (College of Saint Benedict and St. John’s University, 2018).

Erazo, E. C. Stress Reappraisal and Mindfulness Buffer Psychobiological Responses to Social Threat (University of Nevada, 2017).

Griffin, S. M. & Howard, S. Instructed reappraisal and cardiovascular habituation to recurrent stress. Psychophysiology 58, e13783. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13783 (2021).

Gurera, J. W. & Isaacowitz, D. M. Arousal reappraisal in younger and older adults. Psychol. Aging 37, 350–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000674 (2022).

Hangen, E. J., Elliot, A. J. & Jamieson, J. P. Stress reappraisal during a mathematics competition: Testing effects on cardiovascular approach-oriented states and exploring the moderating role of gender. Anxiety Stress Coping 32, 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2018.1530049 (2019).

Jacquart, J., Papini, S., Freeman, Z., Bartholomew, J. B. & Smits, J. A. J. Using exercise to facilitate arousal reappraisal and reduce stress reactivity: A randomized controlled trial. Mental Health Phys. Act. 18, 100324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100324 (2020).

Mesghina, A. et al. Distressed to distracted: Examining undergraduate learning and stress regulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. AERA Open 7, 23328584211065720. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211065721 (2021).

Mesghina, A., Au Yeung, N. & Richland, L. E. Performing up to par? Performance pressure increases undergraduates’ cognitive performance and effort. J. Appl. Res. Memory Cogn. 11, 554–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/mac0000023 (2022).

Reza, M. et al. Exam eustress: Designing brief online interventions for helping students identify positive aspects of stress. Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 439; https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581368 (2023).

Taber, Z. Does Math Anxiety Moderate the Effect of an Online Arousal Reappraisal Intervention on Math Performance? (Georgia State University, 2021).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Taylor & Francis, 2013).

Viechtbauer, W. Bias and efficiency of meta-analytic variance estimators in the random-effects model. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 30, 261–293. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986030003261 (2005).

Knapp, G. & Hartung, J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat. Med. 22, 2693–2710. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1482 (2003).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2023).

Balduzzi, S., Rücker, G. & Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evid.-Based Ment. Health 22, 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117 (2019).

Sambunjak, D., Cumpston, M. & Watts, C. Module 6: Analysing the data in Cochrane Interactive Learning: Conducting an Intervention Review. (Cochrane, Bern, 2017).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03 (2010).

Pustejovsky, J. E. & Tipton, E. Small-sample methods for cluster-robust variance estimation and hypothesis testing in fixed effects models. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 36, 672–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2016.1247004 (2018).

Duval, S. & Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56, 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x (2000).

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 (1997).

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686 (2019).

Harrer, M., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T. & Ebert, D. D. dmetar: Companion R Package For The Guide 'Doing Meta-Analysis in R'. http://dmetar.protectlab.org/ (2019).

Dickerson, S. S. & Kemeny, M. E. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol. Bull. 130, 355–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355 (2004).

Helgeson, V. S. Gender, stress, and coping. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping (ed. Folkman, S.) 63–85 (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Matud, M. P. Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 37, 1401–1415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.010 (2004).

Webb, T. L., Miles, E. & Sheeran, P. Dealing with feeling: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation. Psychol. Bull. 138, 775–808. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027600 (2012).

Harris, R. B. et al. Can test anxiety interventions alleviate a gender gap in an undergraduate STEM course?. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 18, 35. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-05-0083 (2019).

Gavac, S. Trigger Warnings in the Classroom: Assessing the Roles of Appraisals and Stress Mindsets (University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2020).

Sari, İ. Perceived Challenges and Threats in Math Settings: Investigating the Effects of Cognitive Reappraisal Instructions on Math Anxiety (Bilkent University, 2022).

Herrmann, K. Stressed for Success: An Anxiety Reappraisal Video Intervention for Undergraduates (Duke University, 2019).

Omar, Y. A Cognitive and Behavioral Intervention for Smoking craving (The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, 2018).

Simonsohn, U., Nelson, L. D. & Simmons, J. P. P-curve and effect size: Correcting for publication bias using only significant results. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9, 666–681. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614553988 (2014).

Vogel, D. & Homberg, F. P-Hacking, P-Curves, and the PSM–performance relationship: Is there evidential value?. Public Adm. Rev. 81, 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13273 (2021).

Conroy, D. & Hagger, M. S. Imagery interventions in health behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 37, 668–679. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000625 (2018).

Bosshard, M. et al. From threat to challenge—Improving medical students’ stress response and communication skills performance through the combination of stress arousal reappraisal and preparatory worked example-based learning when breaking bad news to simulated patients: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychol. 11, 153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01167-6 (2023).

Raio, C. M., Orederu, T. A., Palazzolo, L., Shurick, A. A. & Phelps, E. A. Cognitive emotion regulation fails the stress test. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 15139–15144. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1305706110 (2013).

Sheppes, G., Scheibe, S., Suri, G. & Gross, J. J. Emotion-regulation choice. Psychol. Sci. 22, 1391–1396. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611418350 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B. and P.G. have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. M.B. drafted the first version of the manuscript. P.G. has substantially revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the submitted version (and any substantially modified version that involves the author's contribution to the study) and have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author's own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bosshard, M., Gomez, P. Effectiveness of stress arousal reappraisal and stress-is-enhancing mindset interventions on task performance outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep 14, 7923 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58408-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58408-w

This article is cited by

-

Stress is wrecking your health: how can science help?

Nature (2025)

-

A randomized controlled trial evaluating stress arousal reappraisal and worked example effects on psychophysiological responses during breaking bad news

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A semi-randomised control trial assessing psychophysiological effects of breathwork and cold immersion

Scientific Reports (2025)