Abstract

Climate change is one of the major drivers of biodiversity loss. Among vertebrates, amphibians are one of the more sensitive groups to climate change due to their unique ecology, habitat requirements, narrow thermal tolerance and relatively limited dispersal abilities. We projected the influence of climate change on an endemic toad, Malabar Tree Toad (Pedostibes tuberculosus; hereafter MTT) from the Western Ghats biodiversity hotspot, India, for two different shared socio-economic pathways (SSP) using multiple modeling approaches for current and future (2061–2080) scenarios. The data used predominantly comes from a citizen science program, ‘Mapping Malabar Tree Toad’ which is a part of the Frog Watch citizen science program, India Biodiversity Portal. We also evaluated the availability of suitable habitats for the MTT in Protected Areas (PAs) under the current and future scenarios. Our results show that annual precipitation was the most important bioclimatic variable influencing the distribution of MTT. We used MaxEnt (MEM) and Ensemble (ESM) modeling algorithms. The predicted distribution of MTT with selected environmental layers using MEM was 4556.95 km2 while using ESM was 18,563.76 km2. Overlaying PA boundaries on predicted distribution showed 37 PAs with 32.7% (1491.37 km2) and 44 PAs with 21.9% (4066.25 km2) coverage for MEM and ESM respectively. Among eight future climate scenarios, scenarios with high emissions showed a decreased distribution range from 33.5 to 68.7% of predicted distribution in PAs, while scenarios with low emissions showed an increased distribution range from 1.9 to 111.3% in PAs. PAs from the Central Western Ghats lose most suitable areas with a shift of suitable habitats towards the Southern Western Ghats. This suggests that MTT distribution may be restricted in the future and existing PAs may not be sufficient to conserve their habitats. Restricted and discontinuous distribution along with climate change can limit the dispersal and persistence of MTT populations, thus enhanced surveys of MTT habitats within and outside the PAs of the Western Ghats are an important step in safeguarding the persistence of MTT populations. Overall, our results demonstrate the use of citizen science data and its potential in modeling and understanding the geographic distribution and the calling phenology of an elusive, arboreal, and endemic amphibian species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, amphibians are one of the most threatened taxa of vertebrates. According to Luedtke et al.1, 40.7% of the world’s amphibians (8011 species) are globally threatened. Factors like agriculture, timber and plant harvesting and infrastructure development have threatened amphibians1. In addition, habitat fragmentation, disease, pollution, and resulting morphological deformities and climate change have led to the decline of amphibian populations in the past four decades2. Amphibians are particularly sensitive to environmental change due to their unique habitat requirements, narrow thermal tolerance, and relatively limited dispersal abilities3. Particularly, frogs from tropical and subtropical forests have higher climatic debts with greater risks of extinction3.

For effective conservation of any species, understanding its distribution is a prerequisite. While the collection of species occurrence data is time-consuming and costly, citizen science initiatives can provide data at less cost, covering significantly larger areas, however, these data collection being non-random can be biased towards particular locations4. For effective monitoring of amphibians, many citizen science programs have been initiated. Such studies can provide useful ecological data on the distribution range of species, population trends, and patterns and drivers of biotic changes, thus aiding in the management and conservation of the species5. Amphibian citizen science programs have helped in documenting rare and threatened frogs as well as the decline in their native ranges6. Citizen science data have also informed the understanding of the breeding phenology of frogs7. For most anurans, breeding phenology is known through their vocalization, and abiotic variables like temperature and precipitation influence the vocalization in frogs8. Climate changes can lead to either early or late onset of breeding in amphibians which can cause changes in population structure and population decline in some species9. Thus, it is important to collect breeding phenology data of amphibians to gain a better understanding of the impact of climate change on their ecology.

The Western Ghats of India is a global biodiversity hotspot10 and is witnessing considerable impacts of climate change on its biodiversity. In a review of future climate impact on India’s biodiversity11, taxonomic groups and species-specific to the Western Ghats are discussed. It included plants12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, mammals23,24,25, birds26,27, invertebrates28 and reptiles29. However, there are relatively fewer studies on the impact of climate change on the species-rich amphibians of the Western Ghats. The Western Ghats harbours 252 species of amphibians, out of which 17 are critically endangered and 40 species are data deficient30. Despite tremendous diversity, the ecology and distribution range of many amphibians in the Western Ghats are poorly understood. To bridge this gap, along with the ongoing ecological research, we initiated a citizen science study, Frogwatch, in 2012 through the India Biodiversity Portal (frogwatch.indiabiodiversity.org). Within Frogwatch, an initiative called Mapping Malabar Tree Toad was launched in 2014 by Gubbi Labs LLP and Earth Watch India, which was funded in 2020 by The Habitats Trust to gather data about the endangered and endemic Malabar Tree Toad, Pedostibes tuberculosus.

The Malabar Tree Toad (Pedostibes tuberculosus Günther, 1876) is the only species in the monotypic genus Pedostibes31. The toad has the unique capability to climb trees unlike most other toads in the Western Ghats that are ground-dwelling. It can be found along streams, on trees, and in tree cavities at a height of about 30 cm –10 m above the ground, in evergreen to moist deciduous forests at an altitude ranging from 50 m to over 1000 m above sea level (KVG, personal observations). After the initial description by Günther in 1876, the species was not documented for more than 100 years. In 1980, the species was rediscovered from Silent Valley National Park, Kerala State by S.K. Bhattacharya32. Even after the rediscovery in 1980, very few observations were available until 202033,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. A few studies have been carried out on MTT’s breeding biology38,42, distribution37,43, taxonomic reevaluation and phylogenetic position31,44. Recently, the distribution of MTT was modeled and the area of occupancy and the extent of occurrence were qualitatively estimated as ‘nearly throughout the Western Ghats’41. However, the data was limited to 31 occurrence points sparsely distributed across the Western Ghats with no predictions of their potential distribution in the future. In this study, using a large number of occurrence points (> 600) from nearly a decade of citizen science data, we revisit the distribution of MTT using multiple modeling approaches and forecast the influence of climate change on the habitat suitability for the MTT. We also evaluated the influence of climatic variables on the calling phenology of MTT from the data obtained through the Mapping MTT project as it showed an interesting trend of a pre-rainy season calling population and a rainy season calling population along the latitudinal gradient of the Western Ghats.

Overall the objectives of this study were to (1) re-assess the distribution of MTT using the data obtained through a citizen science initiative, (2) to understand the current distribution and predict the future distribution of MTT under different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) adopted by Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) using different model algorithms, (3) to understand the influence of bioclimatic and environmental variables on calling phenology of MTT and (4) to assess the coverage of the existing protected area network of the current and future distribution scenarios of MTT.

Methods

Data collection and preparation

Occurrence points

We used a total of 655 observations of MTT from various Citizen Science platforms as listed in Table 1. Observations from published scientific papers as well as from Citizen Science platforms are collated between the year 1876 and 27th June 2022 across the Western Ghats. Location points without specific latitude and longitude or the closest landmark were not used. Each location point and observation record were verified based on the photograph/audio/video before including for further analysis. All uncertain observations were not used in the study. Data from The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and Mapping Malabar Tree Toad (MMTT) programme, which is part of Frog Watch, India Biodiversity Portal (IBP), were integrated on 17th April 2019. Any occurrence data on GBIF before this period will be unique to GBIF. The observation data having the date, location and identification linked with a taxon and with two or more people agreeing/and or being validated by an expert on MMTT gets reflected in the GBIF database. There were 286 such data points in GBIF from MMTT. Observations not validated by an expert remain in MMTT. In addition, there were multiple observations from the same locality, posted at different times and across multiple citizen science platforms. Hence, as a first step, we removed duplicate points from individual data sources as listed in Table 1 and then removed duplicate and uncertain data points across databases. To avoid sampling bias and reduce model overfitting, we thinned occurrence points to within 1 km of each other (at least one data point will be available for a grid) using R45 and the spThin package46. This resulted in 190 occurrence points that were used for further analysis (Fig. 1). These occurrence points were recorded between the years 2003 and 2022, with most of the occurrence points from the years 2020 and 2022. Based on our field observations of call phenology of MTT in the Western Ghats over the last 10 years, the Southern MTT populations (south of 13°N) started calling between mid-February and early March whereas the Northern MTT populations (north of 13°N) started calling only by early June. We applied this categorization to the occurrence points from citizen science data (Fig. 1).

Environmental layers

We used 37 environmental layers, relevant to the distribution of MTT. These were 19 bioclimatic, 12 Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) representing each month from the year 2022, aspect and slope (derived from Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of Hydrological layer), elevation, forest canopy height, global vegetation cover and Land use and Land cover classification (LULC) from the year 2022. The current and future bioclimatic layers were downloaded from WorldClim version 2.1 (https://www.worldclim.org/data/worldclim21.html). DEM, NDVI and LULC (Categorical variable) layers were downloaded from USGS (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/). Global vegetation cover was downloaded from Google Earth Engine (https://earthengine.google.com/), and Forest canopy height was downloaded from earth-data Spatial Data Access Tool (https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/learn/use-data/tools). The LULC categories are as follows; 1: Deciduous Broadleaf Forest, 2: Cropland, 3: Built-up Land, 4: Mixed Forest, 5: Shrubland, 6: Barren Land, 7: Fallow Land, 8: Wasteland, 9: Water Bodies, 10: Plantations, 11: Aquaculture, 12: Mangrove Forest, 13: Salt Pan, 14: Grassland, 15: Evergreen Broadleaf Forest, 16: Deciduous Needleleaf Forest, and 17: Permanent Wetlands. We used the Protected Area (PA) vector layer (http://overpass-turbo.eu/s/NPW, version 0.6, January 2024) to estimate the MTT distribution within the PA network.

For future bioclim data, we used downscaled Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) datasets48, with data chosen based on two shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP 1.2.6 and SSP 5.8.5). SSP 1.2.6 pathway assumes low GHG emissions, and a temperature increase of about 1.7 °C, while SSP 5.8.5 assumes very high GHG emissions, CO2 emissions will triple by 2075, and temperature will rise by 2.4 °C. Within these two SSPs, we chose two global circulation models (GCMs) for the years 2061–208049. These are 1. Model for Interdisciplinary Research on Climate, Earth System version 2 for Long-term Simulations (MIROC-ES2L) and 2. Hadley Centre Global Environment Model in the Global Coupled configuration 3.1 (HadGEM3-GC31-LL). MIROC-ES2L considers explicit carbon and nitrogen cycles for land, and the biogeochemical components are interactively coupled with physical climate components, allowing climate-biogeochemical feedback to be considered50 with a lower equilibrium climate sensitivity range (2.7 °C). Global mean surface temperature, ocean heat content, sea ice extent, ice sheet mass balance, permafrost extent, snow cover, North Atlantic Sea surface temperature and circulation, and decadal precipitation are all included in HadGEM3-GC31-LL51 with a higher equilibrium climate sensitivity (5.6 °C). Future bioclimatic layers were downloaded as single Geo TIFF files, which were then extracted to 19 future bioclimatic layers using the GDAL 'Raster Translation' function in QGIS. All the layers had a spatial resolution of 30 arc-seconds. The region of interest (ROI) is rectangular as it uses minimum and maximum values of latitude and longitude to cover the length and breadth of the Western Ghats (Latitude Max: 23.2036°N, Min: 8.0765°N, Longitude Max: 79.1200°E, Min: 72.3371°E) and hence it is beyond the exact boundary of the Western Ghats. The ROI accommodated a few MTT observations that fell outside the Western Ghats boundary. It was created using country-level spatial data from diva-gis.org. All environmental layers were cropped to ROI using the raster conversion with mask layer function in QGIS 3.24.3 'Tisler'.

Collinearity test

All the cropped layers (37) were tested for multicollinearity with ENMTools 1.1.0 software (https://github.com/danlwarren/ENMTools.git), and the layers with Pearson Correlation Coefficients (r) of ± 0.8 or higher were considered highly correlated and removed from the next iteration of the multicollinearity test. Finally, 24 layers with r value less than ± 0.8 were selected for distribution modelling, including 10 bioclimatic, and 9 NDVI along with aspect, slope, elevation, global vegetation cover and LULC classification (Multicollinearity tests are provided in Supplementary Table 2). Only these 10 bioclimatic layers were used for the future distribution of MTT different climate scenarios.

Modeling algorithms

We used nine modeling algorithms from ESM and the standalone MEM algorithm. We used machine learning modeling algorithms built within the Ensemble model. The details of each algorithm are based on52,53 viz., Artificial Neural Networks (ANN, A single-hidden-layer neural network that uses five-fold internal cross-validation to choose the best number of units in the hidden layer and weight decay, that control model complexity54), Classification Tree Analysis (CTA, a decision tree model fits complex trees with many nodes55), Flexible Discriminant Analysis (FDA, fits a Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS) model and then performs dimensionality reduction before attempting classification56), Generalized Additive Model (GAM, a regression model that fits smoothed additive response curves, allowing no interactions between covariates57), Generalised Boosting Models (GBM, it repeatedly fits many decision trees to improve the accuracy of the model. For each new tree in the model, a random subset of all the data is selected using the boosting method and the input data are weighted in such a way that data that was poorly modeled by previous trees has a higher probability of being selected in the new tree58), Generalised Linear Models (GLM, a regression model that fits quadratic response curves with no interactions between covariates, with stepwise backward selection using Akaike's information criterion59), Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS, a regression model that fits smoothed additive response curves, allowing no interactions between covariates, can fit complex response curves by joining together linear segments60), Surface Range Envelope (SRE, is an envelope-style method and presence-only model that uses the environmental conditions of locations of occurrence data to profile the environments where a species can be found61), Breiman's Random Forest for classification and regression (RF, is a machine-learning method that ensembles predictions from 500 classification trees, fitted on randomly selected subsets of all training data. Individual trees are controlled to have at least five data points in their terminal nodes but are otherwise allowed to grow as many nodes as possible62). We did not use built-in MaxEnt in the ESM as we could not customize parameters for MaxEnt and we were getting ‘failed’ results for MaxEnt, hence we used MaxEnt 3.4.4 standalone modeling algorithm. Using these algorithms, we tested the following—(1) The distribution of MTT using 24 environmental layers and (2) Future MTT distribution using two different SSPs and GCMs. For estimating the distribution of Northern and Southern Western Ghats populations of MTT, we restricted the analysis to the MEM algorithm.

MaxEnt Modeling (MEM)

We used MaxEnt 3.4.463, a maximum entropy modeling algorithm using presence-only records. It has been widely used to model species distributions for its excellent predictive performance64, ability to characterize probability distributions from incomplete information, use of both continuous and categorical variables to model a continuous prediction, and effectiveness even with small sample sizes65. We created a bias file using the R42, Rstudio, and ENMEval package 66 to account for sampling bias in the occurrence data. This file had the same geographical extent as that of environmental layers. For testing and training data sets, using a random test percentage function 75% of the data were set for training and 25% for testing. The regularization multiplier was set to 1 and the maximum number of background points (Pseudo-Absence) was set to 10,000 points. Replicates were set to 10 to achieve maximum model fitting. Each model was run through 5000 iterations with a convergence threshold of 0.00001. We chose cloglog as a running algorithm that gives a probability of occurrence estimate between 0 and 1, and the output is saved in .asc format. For the remaining parameters, we used the default setting in MEM. We created binary maps with a user-defined threshold of 0.8 derived from the least valued ROC (Receiver Operator Characteristic) plot as described in65. As MTT is a widely distributed species, we used the same threshold value for present and future predictions as well as for both modeling approaches. Present and future distribution modelings were carried out keeping the same setting of background points, percentage testing and training data. However, future distribution was made using 10 bioclimatic layers. In addition to AUC values generated from MEM results, pROC metrics were also calculated using ‘NTBOX’67 with 100 replicates at 5%, 10%, and 15% omission proportions, where 1 represents random performance68. To measure niche overlap and identity, Schoener’s D metric and Hellinger-based I index were estimated using ENMTools 1.3. The D-index measures the overlap of the predicted suitable area and represents the proportion of niche coincidence between them, wherein 0 indicates no niche overlap and 1 indicates complete niche overlap. And I index tests whether the habitat suitability scores (D) generated by two models exhibit statistically significant ecological differences (0—no similarity to 1—complete similarity)69,70,71.

Ensemble modeling (ESM)

We used the ShinyBIOMOD available on https://gitlab.com/IanOndo/shinybiomod72,73,74 package in R to perform ESM. Nine algorithms namely ANN, CTA, FDA, GAM, GBM, GLM, MARS, SRE, and RF were used. Evaluation metrics like True Skill Statistics (TSS), Cohen’s kappa (KAPPA), and Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) were recorded for each model algorithm75,76,77. The model performance for nine individual models was evaluated by TSS, KAPPA, ROC values and the variable of importance was examined. Individual models were then subjected to ESM and this resulted in three models-ESM Mean by TSS, ESM Mean by ROC and ESM Mean by KAPPA. Each model output was thresholded for binary presence/absence predictions by applying a threshold to maximize the true positive rate (sensitivity) and true negative rate (specificity) across the range of 0.8 to 1. Pixels with probability values less than the threshold (0.8) were classified as absences, while pixels with probability values greater than the threshold were classified as presences. TSS, ROC percentage (here AUC), and KAPPA were used to calculate model accuracies and true presence, true absence, false positive, and false negative points for each binary map obtained. AUC/ROC values between 0.6 and 0.7 are considered “fair,” while values between 0.7 and 0.8 are considered “good”75,77. TSS ranges from − 1 to 1, with 0 indicating that the model performs no better than random guesses76. The predictors were identified by analyzing the variable importance for each model and ESM. The generated binary maps were used to analyze the present and future predictions. TSS matrices were used to understand the importance of each model in ESMpredictions, where TSS with the highest value for individual models were regarded as models with the greatest influence in ESM. Figure 2 provides a schematic representation of the methods used in the study.

Results

MEM forecasting

Figure 3A depicts the predicted habitat suitability map of MTT with red color indicating high suitability (≥ 0.8). For MEM with selected environmental layers all models had a higher mean AUC value (0.981–0.991) from 10 replications. For the same model, pROC values were 1.975 ± 0.003 at 5%, 10% and 15% omission proportions respectively. Overall, the most significant and contributing variables were annual precipitation (Bio 12, 50.43% contribution) and vegetation cover (13.79% contribution). Table 2 provides the details of model performance and Table 3 provides the contribution of selected environmental variables and selected bioclimatic layers for the models. MEM predicted a total area of 4556.95 km2 with selected environmental layers, with 97.5% of the MTT distribution within the Western Ghats (Table 4).

MEM future prediction

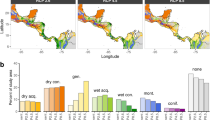

The future climate models (both SSPs and GCMs) tend to shift latitudinally from the present distribution (Fig. 3B–E). Suitable areas under MIROC-ES2L GCM for SSP scenarios tend to shift towards the north whereas HadGEM3-GC31-LL tends to shift more towards the south of the Western Ghats. For SSP 1.2.6, the suitable areas for MTT increased by 54.99% and 59.73% under MIROC-ES2L and HadGEM3-GC31-LL GCMs respectively. However, for SSP 5.8.5, MIROC-ES2L and HadGEM3-GC31-LL showed a decrease in suitable areas by 72.28% and 48.85% respectively. Table 2 provides the model performance for each model and Table 4 provides the area changes for different models.

ESM forecasting

Comparison of individual distribution models within ESM

All models with selected environmental layers had a ROC value of more than 0.97 except CTA (0.884) and SRE (0.692). MARS algorithm contributed most towards the ESM (TSS = 0.911). Model performance analysis is shown in Table 5. The most significant and contributing variable for individual models with selected environmental layers was annual precipitation (Bio 12) except for GLM which had Mean Diurnal Range (Bio 2) as the significant variable and ANN, SRE algorithms which had NDVI April as the significant variable.

ESM performance

Three models were generated by choosing TSS, ROC and KAPPA as the evaluation matrices for the mean probability distribution. All three of the ESMs with selected environmental layers had ROC and TSS values greater than 0.90. Model performance analysis is provided in Table 5. For all of them, annual precipitation (Bio 12) was the most important variable followed by precipitation in the warmest quarter (Bio 18). The performance of ESMs is provided in Table 6 and environmental variables of importance for the ESMs are shown in Table 7.

ESM forecasting

Figure 4A depicts the predicted habitat suitability map of MTT. A binary map created with a threshold of 0.80 shows a total area projected as 18,563.76 km2 for ESM with selected environmental layers in which 93.2% of the distribution falls within the Western Ghats.

ESM – future predictions

The suitable area for MTT decreased under both GCMs and SSPs except HadGEM3-GC31-LL SSP 1.2.6 (Fig. 4B–E). For SSP 1.2.6, suitable area showed a decrease of 6.38% under MIROC-ES2L, while, it showed an increase of 45.71% under HadGEM3-GC31-LL GCMs. For SSP 5.8.5, MIROC-ES2L and HadGEM3-GC31-LL suitable areas showed a decrease of 61.62% and 41.3% respectively. For both GCMs and SSPs, the future prediction extends the distribution of suitable habitats of MTT towards the north by more than 100 km and to the south by approximately 25 km from its recorded distribution (Table 4).

Influence of bioclimatic and environmental variables on calling phenology of MTT

For selected environmental layers, annual precipitation (Bio 12, 53.39% contribution) and precipitation of the driest month (Bio 14, 11.48% contribution) were the highest contributing variables for the Northern Western Ghats (NWG) population. For the Southern Western Ghats (SWG), annual precipitation (Bio 12, 23.07% contribution) and vegetation cover (21.65% contribution) were the highest contributing variables (Fig. 5A). Table 8 provides the details of the permutation and combination of selected environmental variables and Table 9 provides the model performance.

In future climate scenarios, under MEM, the Northern Western Ghats showed an increase in suitable areas for both SSPs and GCMs, whereas there was a decrease in suitable habitats for Southern Western Ghats (Table 4, Fig. 5B–E). Predicted models were tested for niche overlap and niche identity using ENM Tools 1.3. The analysis suggested there is a very minimal overlap between the Northern and the Southern Western Ghats populations. In future scenarios, this trend will continue. The niche identity tests suggested that the Northern and Southern Western Ghats populations have zero to very low similarity in present and future scenarios. Lower values in the I index suggest that the niche overlap predicted by ENM Tools is statistically significant. The Schoener’s D index for niche overlap and niche identity/similarity index (Hellinger-based I) are provided in Table 10.

Coverage by the protected area network of the distribution of MTT and its association with Land Use and Land cover classes

Around 17.44% (18,795.77 km2) of the Western Ghats (Total area—107,783.72 km2) are covered by the 65 PAs. Using MEM with selected environmental layers, we found that 37 PAs cover 32.7% of the total predicted distribution of MTT (4556.95 km2). The percentage coverage is much smaller using ESM, with 44 PAs covering only 21.9% of the larger total predicted area of distribution of MTT (18,563.76 km2). Most of the predicted distribution of MTT falls outside the PAs (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 3). In future scenarios using MEM, under SSP 1.2.6, both scenarios show increased coverage in PAs (2592.28 km2 and 3151.86 km2 respectively), but under SSP 5.8.5, both scenarios show decreased coverage in PAs (838.95 km2 and 466.73 km2 respectively). In future scenarios using ESM, under SSP 1.2.6, scenario MIROC-ES2L and HadGEM3-GC31-LL showed increased coverage in PAs (4144.17 km2 and 4873.69 km2 respectively), but under SSP 5.8.5, both scenarios show decreased coverage in PAs (2012.81 km2 and 2704.20 km2 respectively). Details are provided in Table 4.

We looked at individual PAs with suitable habitats for MTT. In MEM, four large PAs contributed to 71% of predicted distribution, namely, Kali Tiger Reserve (TR—Tiger Reserve) (416.99 km2), Kudremukh National Park (NP—National Park) (253.67 km2), Sharavathi Valley Wildlife Sanctuary (WS—Wildlife Sanctuary) (146.73 km2) and Someshwara WS (250.36 km2) in Karnataka. In the Ensemble model, 10 PAs contributed 77.7% of the predicted distribution. They were Mhadei WS (151.71 km2) and Netravali WS (126.01 km2) in Goa State, Bhimgad WS (108.6 km2), Brahmagiri WS (112.74 km2), Kali TR (1010.55 km2), Kudremukh NP (633.36 km2), Mookambika WS (257.82 km2), Sharavathi Valley WS (240.41 km2), Someshwara WS (329.94 km2) in Karnataka State and Kalakad Mundanthurai TR (187.35 km2) in Tamil Nadu state. In both the MEM and ESM, Kali TR, Kudremukh NP, Someshwara WS and Sharavathi Valley WS have the highest predicted distribution of MTT. Details are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

In future climate scenarios using MEM, under the SSP 1.2.6, MIROC-ES2L and HadGEM3-GC31-LL, Kali TR, Kudremukh NP and Someshwara WS showed increased distribution, along with Mookambika WS (252.85 km2 and 281.03 km2 in both the scenarios). However, under SSP 5.8.5, in both scenarios, Kali TR (89.53 km2 and 0 km2), Sharavathi Valley WS (76.27 km2 and 0.83 km2) and Someshwara WS (124.35 km2 and 0 km2) showed a decrease in suitable habitats.

In future climate scenarios using ESM, under the SSP 1.2.6, MIROC-ES2L and HadGEM3-GC31-LL, Kudremukh NP, Mhadei WS, Mookambika WS, Sharavathi Valley WS, Someshwara WS, Netravali WS and Mollem NP showed increased area of distribution, while Brahmagiri WS and Kalakad Mundanthurai TR, showed decrease in suitable habitats. Interestingly, under SSP 5.8.5 with MIROC-ES2L and HadGEM3-GC31-LL, except for Anamalai TR (153.37 km2), Indira Gandhi WS (147.56 km2) and Brahmagiri WS (135.96 km2) which are all part of Southern Western Ghats, all other PAs showed a decrease in suitable habitats.

The variable importance of LULC for the Northern Western Ghats populations, and Southern Western Ghats populations and when both regions were combined showed 7.25%, 4.90%, and 2.56% contribution respectively. Although the contribution of LULC was less, evergreen broad-leaved forests (category 15) and plantations (category 10) were the two most important categories of model prediction. For Northern Western Ghats populations, evergreen broad-leaved forests (category 15) were the most important category for the distribution. Even though most of the distribution fell within the evergreen forests (63.60%), few points were also falling in plantations (14.23%), croplands (6.75%), mixed forests (8.41%), grasslands (2.97%), water bodies (2.60%) and built-up lands (1.56%). This demonstrates that MTT also occurs in human-modified habitats. The distribution in the Southern Western Ghats showed an association with grasslands, probably due to over-prediction by the other variables. The result could also be due to less permutation importance of LULC for the Southern Western Ghats (Fig. 6A–C).

According to MEM most of the MTT distribution (both present and future) fell within the Western Ghats. However, MEM with selected environmental layers showed 2.49% of the total distribution outside the Western Ghats, e.g., coastal areas. The future climate scenarios also showed a similar pattern under MIROC-ES2L GCM, 2.32% and 0.06% of SSPs 1.2.6 and 5.8.5 fell outside the Western Ghats. Under HadGEM3-GC31-LL GCM for both SSPs, MTT’s distribution was restricted to the Western Ghats.

Discussion

Role of Citizen Science data in reassessing the distribution of MTT

Studies have suggested that amphibians inhabiting forests exclusively as compared to forests and open areas will lose their habitats to climate change due to the loss of available microhabitats78. Overall, there is a lack of data on the influence of climate change on amphibians from the South Asian region78. Although India is known for high amphibian diversity, few studies have predicted the impact of climate change on the future distribution of Indian amphibians79. To our knowledge, this study is the first one to understand how future climate can influence the distribution of endemic toads like MTT using data from citizen science initiatives. Citizen science data have often helped in the conservation and management of species80. They have been useful in conservation education and outreach. As a part of the Mapping Malabar Tree Toad project’s (MMTT project, https://frogwatch.indiabiodiversity.org/) citizen science initiatives, authors (GKV, HS, and RC) undertook conservation education and capacity-building activities across the Western Ghats to motivate and arouse interest among residents. These outreach activities have resulted in the active participation of college students, forest department officials, and amphibian researchers in the monitoring of MTT. This led to an increase in MTT observations from 4 in 2014 to 286 in the MMTT project alone as of January 2023, thus obtaining a large amount of distribution data through the citizen science initiative. As ‘presence only’ data collected opportunistically from citizen science programs can be erroneous, the data points used in this study were filtered and curated by batrachologists and amphibian researchers (GKV, HS, Thomas Vattakaven) through photos, calls, georeferenced points of MTT and re-confirming with the observers through emails for accuracy. The increased number of occurrence points helped in prediction accuracy, reducing bias and helping in better understanding of the distribution of MTT. Such community participation will create interest among citizens and enhance awareness about the species and their habitats. More such studies involving local communities along with scientific studies on Indian amphibians will help with the conservation of amphibians.

Understanding the current and the future distribution of MTT under different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs)

In this study, we used both MEM and ESM approaches to understand the potential distribution of MTT. Considering AUC values as the model’s fitness, we found that both approaches had AUC values greater than 0.9, suggesting the robustness of the results. Studies suggest that ESMapproaches are better than single modeling approaches as they reduce the predictive uncertainty of single models81. However, MEM as a single modeling approach has advantages of being most used modeling approach, works well with presence-only data and easy to use82. Although both approaches gave similar results, ESM showed distribution outside the Western Ghats i.e., in coastal regions as well. Future surveys in coastal regions will help in understanding if the ESM predictions hold true. Both the modeling approaches suggested Annual precipitation (BIO12) and Precipitation of Warmest Quarter (BIO18) as important climatic factors governing the distribution of MTT, suggesting that the distribution of MTT is largely restricted to moist areas of the Western Ghats. Precipitation-based climate variables are often important predictors of amphibian distribution as most amphibians require water for breeding83. Although MTT is a tree toad, during monsoon, particularly, the Northern Western Ghats populations come to the ground to breed in water pools at the edges of the streams generated during the monsoon43 implying that precipitation and moisture provide the necessary conditions for MTT to breed. The study by Chandramouli42 showed that Precipitation of the wettest month (BIO13) and Isothermality (BIO3) were important predictors. The difference in the predictors could be due to the higher sample size of the occurrence points (190 in this study vs 31 by Ref.42). In the present study, vegetation cover was also a significant variable for the MTT distribution contributing 13.79%. Vegetation cover is known to influence amphibian distribution positively by providing good-quality habitats for breeding, protection from predators84 and by providing prey diversity. Vegetation cover provides a buffer against changes in microclimate and loss of vegetation cover can influence the species’ survival85. MTT is adapted to arboreal habitats, specifically large trees, suggesting that higher canopy and vegetation cover are important microhabitats for them43.

Global climate change has been one of the challenging environmental problems of the twenty-first century and amphibians are known to be one of the vulnerable groups to climate change as their distribution ranges can shift, contract or undergo local extinction. According to this study, presently, central Western Ghats has suitable areas for MTT. In future scenarios, suitable habitats of MTT decrease with decreasing precipitation under the MIROC-ES2L as well as HadGEM3-GC31-LL for SSP 5.8.5 (in both MEM and ESM). In contrast, except for MIROC-ES2L SSP 1.2.6 in ESM, suitable habitats increased in MIROC-ES2L and HadGEM3-GC31-LL for SSP 1.2.6. Particularly, the Southern Western Ghats gained suitable habitats under the SSP 1.2.6. due to the predicted increase in monsoon rains in the region86.

Continued monitoring efforts in the Southern Western Ghats will be helpful in understanding if the future MTT distribution matches the prediction of suitable habitats in this region. Overall, the results suggest that the predicted habitat of MTT is likely to be affected due to the changing climate, particularly the reduction of most of its suitable habitats in the high greenhouse gas emission scenarios of the HadGEM3-GC31-LL circulation models.

The role of the protected area network in current and future distribution scenarios of MTT

In this study, we assessed the efficiency of PA networks in securing the distribution of MTT. Under the present conditions, MTT distribution falls within the Western Ghats, however, the protected areas cover less than 32.7% (using MEM) and 21.9% (using ESM) of the predicted distribution of MTT. The present distribution shows suitable habitats in protected areas like Kali TR, Kudremukh NP, Someshwara WS and Sharavathi Valley WS of Karnataka region of the central Western Ghats (Supplementary Table 3) while the PAs from Northern Western Ghats and Southern Western Ghats failed to include much of MTT distribution. Despite the confirmed distribution of MTT in PAs in the Southern Western Ghats, the model was unable to predict the distribution in these PAs. This could be due to (1) shortcoming of the distribution model and not a true lack of habitat suitability within the PAs in these areas, and (2) occurrence data from citizen science not being equally distributed across all PAs. PAs like Kali TR, Sharavathi Valley WLS and Kudremukh NP have more occurrence points than others.

Our study shows that PAs cover a very small part of MTT distribution. In future scenarios, the PAs from the Central Western Ghats lose most of the suitable habitats with a shift of suitable habitats towards the Southern Western Ghats. This suggests that MTT distribution may be restricted in the future and PAs alone may not help conserve their habitats. According to the LULC analysis, MTT is distributed in evergreen forests, and plantations and 9.35% of MTT distribution falls in human-dominated areas. The Western Ghats are facing deforestation and conversion of evergreen forests to agriculture87,88. Therefore, more stringent efforts are needed to protect the evergreen forests from changes in land use and safeguard MTT habitats. As fragmentation of habitats along with climate change can impact the dispersal and persistence of MTT populations, enhanced surveys on habitats within and outside the PAs of the Western Ghats will be an important step in monitoring the MTT populations.

Understanding the correlation of abiotic variables on calling phenology of MTT

For amphibians, call phenology is linked to climate89. Studies have shown that precipitation influences the breeding phenology in amphibians. For example, in Pseudacris maculata, precipitation acted as an environmental cue for opportunistic breeding activities90. Our results suggest that annual precipitation influences the populations of MTT, however, there are subtle differences among precipitation-related bioclimatic variables that distinguish the northern and southern populations and their call phenology. Temperature is also known to influence the breeding phenology in amphibians. A study on the breeding phenology of eastern Ontario frogs showed a shift in calling patterns due to an increase in local temperature91 however in our study temperature was not a significant predictor. For MTT, further studies are needed to understand if changes in local temperature can influence its breeding phenology. Our results also showed that vegetation cover was an important predictor for the Southern Western Ghats populations but not for the Northern Western Ghats populations. Deshpande and Gaitonde43 commented that the Southern Western Ghats populations use tree cavities and Ochlandra clumps as sites for oviposition whereas the northern populations use standing water at the edges of the streams suggesting that not just call phenology, but microhabitat use also differs between the Northern Western Ghats and the Southern Western Ghats MTT populations. Our niche overlap and identity results suggest that both populations are highly distinguishable in their range of distribution spread and not identical. Continuous monitoring of the northern and the southern populations will be needed to understand if climate change and changes in call phenology influence the breeding activities and behaviour of MTT populations.

Conclusions

Using citizen science data, we modeled the distribution of the endemic Malabar Tree Toad (Pedostibes tuberculosus) and predicted the future habitat suitability under the influence of climate change. The potential distribution areas generated in this study, particularly the less sampled areas of the Northern and the Southern Western Ghats should be surveyed to comprehensively determine the distribution of MTT. Understanding of current and future shifts can help in prioritizing the conservation of suitable habitats of MTT and intensive field surveys should be carried out in regions that are outside the currently known range, for example, parts of the Northern and the Southern Western Ghats and low-lying areas outside the Western Ghats for a better understanding of their distribution. The PAs of Western Ghats cover only a small area of MTT distribution and in future most of the PAs, particularly from the Central Western Ghats, are predicted to lose suitable habitats, suggesting that PAs may not be effective in conserving the habitats of MTT. Habitat fragmentation and developmental activities may further degrade the habitats of MTT. We recommend that the predicted suitable habitats should be integrated in the conservation plan for MTT.

References

Luedtke, J. A. et al. Ongoing declines for the world’s amphibians in the face of emerging threats. Nature 622, 308–314. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06578-4 (2023).

Sodhi, N. S. et al. Measuring the meltdown: Drivers of global amphibian extinction and decline. PLoS ONE 3(2), e1636. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001636 (2008).

He, Y., Liao, Z., Chen, X. & Chen, Y. Climatic debts for global amphibians: Who, where and why?. Biol. Conserv. 279, 109929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.109929 (2023).

Zapponi, L. et al. Citizen science data as an efficient tool for mapping protected saproxylic beetles. Biol. Conserv. 208, 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.04.035 (2017).

MacPhail, V. J. & Colla, S. R. Power of the people: A review of citizen science programs for conservation. Biol. Conserv. 249, 108739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108739 (2020).

Rowley, J. J. et al. FrogID: Citizen scientists provide validated biodiversity data on frogs of Australia. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 14(1), 155–170 (2019).

Liu, G., Kingsford, R. T., Callaghan, C. T. & Rowley, J. J. Anthropogenic habitat modification alters calling phenology of frogs. Glob. Change Biol. 28(21), 6194–6208. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16367 (2022).

Saenz, D., Fitzgerald, L. A., Baum, K. A. & Conner, R. N. Abiotic correlates of anuran calling phenology: The importance of rain, temperature, and season. Herpetol. Monogr. 20(1), 64–82. https://doi.org/10.1655/0733-1347(2007)20[64:ACOACP]2.0.CO;2 (2006).

Blaustein, A. R. et al. Amphibian breeding and climate change. Conserv. Biol. 15(6), 1804–1809. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2001.00307.x (2001).

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858. https://doi.org/10.1038/35002501 (2000).

Sarkar, D., Jagannivsan, H., Debnath, A. & Talukdar, G. A systematic review on the potential impact of future climate change on India’s biodiversity using species distribution model (SDM) studies: Trends, and data gaps. Biodiversity Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-024-02785-1 (2024).

Gopalakrishnan, R. et al. Impact of climate change at species level: A case study of teak in India. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change 16, 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-010-9258-6 (2011).

Barik, S.K. & D. Adhikari. Predicting the geographical distribution of an invasive species (Chromolaena odorata L. (King) & HE Robins) in the Indian subcontinent under climate change scenarios. in Invasive Alien Plants: An Ecological Appraisal for the Indian Subcontinent (pp. 77–88). (CABI, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845939076.0077

Chitale, V. S., Behera, M. D. & Roy, P. S. Future of endemic flora of biodiversity hotspots in India. PloS One 9, e115264. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115264 (2014).

Remya, K., Ramachandran, A. & Jayakumar, S. Predicting the current and future suitable habitat distribution of Myristica dactyloides Gaertn. using MaxEnt model in the Eastern Ghats, India. Ecol. Eng. 82, 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.04.053 (2015).

Priti, H., Aravind, N. A., Shaanker, R. U. & Ravikanth, G. Modeling impacts of future climate on the distribution of Myristicaceae species in the Western Ghats, India. Ecol. Eng. 89, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.01.006 (2016).

Sen, S., Gode, A., Ramanujam, S., Ravikanth, G. & Aravind, N. A. Modeling the impact of climate change on wild Piper nigrum (Black Pepper) in Western Ghats, India using ecological niche models. J. Plant Res. 129, 1033–1040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-016-0859-3 (2016).

Deb, J. C., Phinn, S., Butt, N. & McAlpine, C. A. The impact of climate change on the distribution of two threatened Dipterocarp trees. Ecol. Evolut. 7, 2238–2248. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2846 (2017).

Lamsal, P., Kumar, L., Aryal, A. & Atreya, K. Invasive alien plant species dynamics in the Himalayan region under climate change. Ambio 47, 697–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1017-z (2018).

Pramanik, M., Paudel, U., Mondal, B., Chakraborti, S. & Deb, P. Predicting climate change impacts on the distribution of the threatened Garcinia indica in the Western Ghats, India. Clim. Risk Manag. 19, 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2017.11.002 (2018).

Pramanik, M., Diwakar, A. K., Dash, P., Szabo, S. & Pal, I. Conservation planning of cash crops species (Garcinia gummi-gutta) under current and future climate in the Western Ghats, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 5345–5370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00819-6 (2021).

Panda, R. M. & Behera, M. D. Assessing harmony in distribution patterns of plant invasions: A case study of two invasive alien species in India. Biodivers. Conserv. 28, 2245–2258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-018-1640-9 (2019).

Sony, R. K., Sen, S., Kumar, S., Sen, M. & Jayahari, K. M. Niche models inform the effects of climate change on the endangered Nilgiri Tahr (Nilgiritragus hylocrius) populations in the southern Western Ghats, India. Ecol. Eng. 120, 355–363 (2018).

Raman, S., Shameer, T. T., Sanil, R., Usha, P. & Kumar, S. Protrusive influence of climate change on the ecological niche of endemic brown mongoose (Herpestes fuscus fuscus): A MaxEnt approach from Western Ghats, India. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 6, 1795–1806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-020-00790-1 (2020).

Subrahmanyam S, ML Das and HN Kumara (2021) Climate change projections of current and future distributions of the endemic Loris lydekkerianus (Lorinae) in peninsular India. Exploring Synergies and Trade-offs between Climate Change and the Sustainable Development Goals 321–358.

Sanjo Jose, V. & Nameer, P. O. The expanding distribution of the Indian Peafowl (Pavo cristatus) as an indicator of changing climate in Kerala, southern India: A modelling study using MaxEnt. Ecol. Indicators 110, 105930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105930 (2020).

Sreekumar, E. R. & Nameer, P. O. Impact of climate change on two high-altitude restricted and endemic flycatchers of the Western Ghats. India. Curr. Sci. 121, 1335–1342 (2021).

Sundar, S., Silva, D. P., de Oliveira Roque, F., Simião-Ferreira, J. & Heino, J. Predicting climate effects on aquatic true bugs in a tropical biodiversity hotspot. J. Insect Conserv. 25, 229–241 (2021).

Srinivasulu, A. & Srinivasulu, C. All that glitters is not gold: A projected distribution of the endemic Indian Golden Gecko Calodactylodes aureus (Reptilia: Squamata: Gekkonidae) indicates a major range shrinkage due to future climate change. J. Threatened Taxa. 8(6), 8883–8892. https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.2723.8.6.8883-8892 (2016).

Dahanukar N and S Molur (2020) JoTT Checklist of amphibians of the Western Ghats (v1.0), 01 January 2020. https://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/checklists/amphibians/westernghats

Chan, K. O., Grismer, L. L., Zachariah, A., Brown, R. M. & Abraham, R. K. Polyphyly of Asian tree toads, genus Pedostibes Günther, 1876 (Anura: Bufonidae), and the description of a new genus from Southeast Asia. PLoS ONE 11(1), e0145903. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145903 (2016).

Pillai, R. Amphibian fauna of silent valley, Kerala S. India. Rec. Zool. Surv. India 84(1–4), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.26515/rzsi/v84/i1-4/1986/161095 (1986).

Inger, R. F., Shaffer, H. B., Koshy, M. & Bakde, R. A report on a collection of amphibians and reptiles from Ponmudi, Kerala, South India. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 81(2), 406–427 (1984).

Das, I. & Whitaker, R. Pedostibes tuberculosus (Malabar tree toad) at Cotegao wildlife Sanctuary, Goa. Herpetol. Rev. 29(3), 173 (1998).

Biju, S. D. A synopsis to the frog fauna of the Western Ghats, India. Indian Soc. Conserv. Biol. Occasional Publ. 1, 1–24 (2001).

Dahanukar, N., Padhye, A., Salelkar, G. & Ghate, H. Aktueller Beleg für die Malabar Baumkröte, Pedostibes tuberculosus Gunther, 1876. Indien. Sauria 26(3), 17–20 (2004).

Gururaja, K. V. & Ramachandra, T. V. Pedostibes tuberculosus (Malabar Tree Toad) advertisement call and distribution. Herpetol. Rev. 37(1), 75–76 (2006).

Dinesh, K. P. & Radhakrishnan, C. New Site Records of the Malabar Tree Toad, Pedostibes tuberculosus Gunther (Amphibia: Anura: Bufonidae), in Western Ghats, India. Rec. Zool. Surv. India 108(1), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.26515/rzsi/v108/i1/2008/159064 (2008).

Sayyed, A. & Nale, A. New distribution record and intergeneric amplexus in the Malabar Tree Toad, Pedostibes tuberculosus Günther 1875 (Amphibia: Anura: Bufonidae). Reptiles Amphibians 24(3), 193–196 (2017).

Dharwadkar, S., Bednarski, C., Inman, D. & Mallapur, G. Malabar tree toad: Occurrence of Pedostibes tuberculosus from the Tillari, northern Western Ghats, Maharashtra, India. Zoo’s Print 34(1), 18–20 (2019).

Chandramouli, S. R. Distribution of two endemic bufonids (Anura: Bufonidae) in the Western Ghats. Taprobanica 9, 222–224. https://doi.org/10.47605/tapro.v9i2.236 (2020).

Deshpande, D. & Gaitonde, N. Breeding biology of Malabar Tree Toad Pedostibes tuberculosus (Anura: Bufonidae) from Castle Rock, Karnataka, India. J. Threat Taxa. 13, 16912–16915. https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.5308.12.13.16912-16915 (2020).

Sreedharan, S., Joseph, J., George, S. & Antony, M. M. New distribution record of the Malabar Tree Toad, Pedostibes tuberculosus Gunther 1875 (Amphibia: Anura: Bufonidae). Reptil. Amphib. 26(3), 250–252. https://doi.org/10.17161/randa.v26i3.14428 (2020).

Chandramouli, S. R. & Amarasinghe, A. T. Taxonomic reassessment of the arboreal toad Genus Pedostibes Günther 1876 (Anura: Bufonidae) and some allied Oriental bufonid genera. Herpetologica 72(2), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1655/HERPETOLOGICA-D-15-00053 (2016).

R Core Team (2022) R: A language and environment for statistical computing.

Aiello-Lammens, M. E., Boria, R. A., Radosavljevic, A., Vilela, B. & Anderson, R. P. spThin: An R package for spatial thinning of species occurrence records for use in ecological niche models. Ecography 38(5), 541–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01132 (2015).

Bhavanarayeni R (2023) Pedostibes tuberculosus Günther, 1876 – Malabar Tree Toad. Gosavi, N., A. Bayani, P. Roy, and K. Kunte (eds.). Amphibians of India, v. 1.05. Indian Foundation for Butterflies. http://www.indianamphibians.org/sp/112/Pedostibes-tuberculosus

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9(5), 1937–1958. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-1937-2016 (2016).

Xin X, J Zhang, F Zhang, T Wu, X Shi, J Li, M Chu, Q Liu, J Yan, Q Ma, and M Wei (2018) BCC BCC-CSM2MR model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP. Version 20220620[1].Earth System Grid Federation. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.1725

Hajima, T. et al. Development of the MIROC-ES2L Earth system model and the evaluation of biogeochemical processes and feedbacks. Geosci. Model Dev. 13(5), 2197–2244. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-2197-2020 (2020).

Andrews, M. B. et al. Historical simulations with HadGEM3-GC3.1 for CMIP6. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 12(6), 95. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001995 (2020).

Hao, T., Elith, J., Lahoz-Monfort, J. J. & Guillera-Arroita, G. Testing whether ensemble modelling is advantageous for maximising predictive performance of species distribution models. Ecography 43(4), 549–558 (2020).

Hallgren, W. et al. The biodiversity and climate change virtual laboratory: Where ecology meets big data. Environ. Model. Softw. 76, 182–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2015.10.025 (2016).

Lek, S. & Guégan, J. F. Artificial neural networks as a tool in ecological modelling, an introduction. Ecol. Model. 120(2), 65–73 (1999).

Breiman, L., J. Friedman, R. Olshen & C. Stone (1984) Classification and Regression Trees. Wadsworth and Brooks, Monterey, CA,

Hallgren, W., Santana, F., Low-Choy, S., Zhao, Y. & Mackey, B. Species distribution models can be highly sensitive to algorithm configuration. Ecol. Model. 408, 108719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2019.108719 (2019).

Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Generalized Additive Models (Taylor & Francis, 1990).

Elith, J., Leathwick, J. R. & Hastie, T. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J. Anim. Ecol. 77(4), 802–813 (2008).

McCullagh, P. Generalized linear models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 95, 1320–1324. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2000.10474340 (1999).

Friedman, J. H. Multivariate adaptive regression splines. Ann. Stat. 19(1), 1–67 (1991).

Booth, T. H. Estimating potential range and hence climatic adaptability in selected tree species. Forest Ecol. Manag. 366, 175–183 (2016).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Phillips S, M Dudík and R Schapire (2022) Maxent software for modeling species niches and distributions (Version 3.4. 1). American Museum of Natural History. New York, NY, USA. Accessed 10 August 2022

Elith, J. et al. Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2006.0906-7590.04596.x (2006).

Chetan, N., Praveen, K. K. & Vasudeva, G. K. Delineating ecological boundaries of Hanuman langur species complex in peninsular India using MaxEnt modeling approach. PLoS ONE 9(2), e87804. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087804 (2014).

Kass, J. M. et al. ENMeval 2.0: Redesigned for customizable and reproducible modeling of species’ niches and distributions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12(9), 1602–1608. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13628 (2021).

Osorio-Olvera, L. et al. ntbox: An r package with graphical user interface for modelling and evaluating multidimensional ecological niches. Methods Ecol. Evolut. 11(10), 1199–1206. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13452 (2020).

Peterson, A. T., Papes, M. & Soberon, J. Rethinking receiver operating characteristic analysis applications in ecological niche modeling. Ecol. Model. 213(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2007.11.008 (2008).

Warren, D. L., Glor, R. E. & Turelli, M. Environmental niche equivalency versus conservatism: Quantitative approaches to niche evolution. Evolution 62(11), 2868–2883. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00482.x (2008).

Warren, D. L., Glor, R. E. & Turelli, M. ENMTools: A toolbox for comparative studies of environmental niche models. Ecography 33(3), 607–611. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06142.x (2010).

Ortega-Andrade, H. M. et al. Insights from integrative systematics reveal cryptic diversity in Pristimantis frogs (Anura: Craugastoridae) from the Upper Amazon Basin. PLoS ONE 10(11), e0143392. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143392 (2015).

Henderson, A. F., Santoro, J. A. & Kremer, P. Ensemble modeling for American chestnut distribution: Locating potential restoration sites in Pennsylvania. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 942766. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.942766 (2022).

Thuiller, W., Lafourcade, B., Engler, R. & Araújo, M. B. BIOMOD—A platform for ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Ecography 32(3), 369–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05742.x (2009).

Thuiller, W., D. Georges, R. Engler, F. Breiner, M.D. Georges, C.W. Thuiller (2016) Package ‘biomod2’. Species distribution modeling within an ensemble forecasting framework. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05742.x

Swets, J. A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 240(4857), 1285–1293. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3287615 (1988).

Allouche, O., Tsoar, A. & Kadmon, R. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: Prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J. Appl. Ecol. 43(6), 1223–1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01214.x (2006).

Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 27(8), 861–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2005.10.010 (2006).

Alves-Ferreira, G., Talora, D. C., Solé, M., Cervantes-López, M. J. & Heming, N. M. Unraveling global impacts of climate change on amphibians distributions: A life-history and biogeographic-based approach. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 987237. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.987237 (2022).

Subba, B., Sen, S., Ravikanth, G. & Nobis, M. P. Direct modelling of limited migration improves projected distributions of Himalayan amphibians under climate change. Biol. Conserv. 227, 352–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.09.035 (2018).

Casula, P. Monitoring and management of Cerambyx cerdo in the Mediterranean region—A review and the potential role of citizen science. Nat. Conserv. 19, 97–110. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.19.12637 (2017).

Thuiller, W., Guéguen, M., Renaud, J., Karger, D. N. & Zimmermann, N. E. Uncertainty in ensembles of global biodiversity scenarios. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 1446 (2019).

Kaky, E., Nolan, V., Alatawi, A. & Gilbert, F. A comparison between Ensemble and MaxEnt species distribution modelling approaches for conservation: A case study with Egyptian medicinal plants. Ecol. Inform. 60, 101150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2020.101150 (2020).

Hedrick, B. P., Estrada, A., Sutherland, C. & Barbosa, A. M. Projected northward shifts in eastern red-backed salamanders due to changing climate. Ecol. Evol. 13(4), e9999. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9999 (2023).

Boissinot, A., Bernard, A. & Lourdes, O. Amphibian diversity in farmlands: Combined influences of breeding-site and landscape attributes in western France. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 269, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2018.09.016 (2019).

Beranek, C. T., Sanders, S., Clulow, J. & Mahony, M. Factors influencing persistence of a threatened amphibian in restored wetlands despite severe population decline during climate change driven weather extremes. Biodivers. Conserv. 31(4), 1267–1287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-022-02387-9 (2022).

Shetty, S., Umesh, P. & Shetty, A. Future transition in climate extremes over Western Ghats of India based on CMIP6 models. Environ. Monitoring Assessment 195(5), 578 (2023).

Jha, C. S., Dutt, C. B. S. & Bawa, K. S. Deforestation and land use changes in the Western Ghats. India. Curr. Sci. 79(2), 231–238 (2000).

Jitendra (2019) Western Ghats at risk: Deforestation data drives home point again. Down to Earth (10 May 2019) (https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/forests/western-ghats-at-risk-deforestation-data-drives-home-point-again-64470)

Gibbs, J. P. & Breisch, A. R. Climate warming and calling phenology of frogs near Ithaca, New York, 1900–1999. Conserv. Biol. 15(4), 1175–1178. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2001.0150041175.x (2001).

Buckley, E. M. B., Gottesman, B. L., Caven, A. J., Harner, M. J. & Pijanowski, B. C. Assessing ecological and environmental influences on boreal chorus frog (Pseudacris maculata) spring calling phenology using multimodal passive monitoring technologies. Ecol. Indic. 121, 107171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107171 (2021).

Klaus, S. P. & Lougheed, S. C. Changes in breeding phenology of eastern Ontario frogs over four decades. Ecol. Evol. 3(4), 835–845. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.501 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Global Biodiversity Information Facility (https://www.gbif.org), iNaturalist (https://inaturalist.org) and Amphibians of India (http://www.indianamphibians.org/sp/112/Pedostibes-tuberculosus) for the data we accessed. HS, RC and KVG would like to thank Thomas Vattakaven and R. Prabhakar for developing www.frogwatch.indiabiodiversity.org. HS, RC and KVG thank The Habitats Trust for a Lesser-known species grant awarded in 2020. We thank the following members of the Mapping Malabar Tree Toad programme for sharing the observation records till June 2022—Abhijith APC, Ajith, Angelina, Anuraj RK, Azaruddin Azu, Chaitanya R, Daimler Pereira, David Raju, Deepak Deshpande, Dhanya V, Dhwani, Divya, C Girish Gowda, Guru Climber, Gururaj, Jonathan, Kesava Murthy, Kesavamurthy N, Makarand Naik, Maneesh M, Nagesh K G Gowda, Nidheesh Chenchery, Nihal Jabin, Nithin Divakar, Raghavendra Jiragale, Raghavendra Pai, Rajkumar KP, Sabu Shettennavar, Sandeep Das, Shashwat Jaiswal, Shaunak Modi, Suhas Hegde, Surya, Surya Narayan, Varad Giri, Vijayakumar Kalappanavar, Vinodh V, Vrinda; Pavan Kumar KS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Mapping Malabar Tree Toad Programme - individuals contributed towards data points for the analysis through a citizen science programme. ACK, PH and KVG conceived and designed the study. ACK ran model algorithms, and prepared tables and figures. ACK and PH wrote the text. ACK, PH, KVG, RC and SH read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

We confirm that all the work is original and that this manuscript has not been submitted for publication elsewhere. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. We have followed all local, national, and international regulations and ethical research practices and there was no collection of specimens. This work was supported by The Habitats Trust and funding was provided to Metastring Foundation. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. Mapping Malabar Tree Toad Programme—individuals contributed towards data points for the analysis through a citizen science programme. ACK, PH and KVG conceived and designed the study. ACK ran model algorithms, and prepared tables and figures. ACK and PH wrote the text. ACK, PH, KVG, RC and SH read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have read the final manuscript and approved it for submission. Data availability—Occurrence data of Malabar Tree Toad (Pedostibes tuberculosus) used in this study are available as open access in the following repositories—https://frogwatch.indiabiodiversity.org/; https://www.gbif.org; https://inaturalist.org; https://indianamphibians.org Environmental Layers used in the study are available as open access in the following repositories—https://www.worldclim.org/data/worldclim21.html; https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/; https://earthengine.google.com/; https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/learn/use-data/tools; Protected Area vector layer—http://overpass-turbo.eu/s/NPW

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aravind, C.K., Priti, H., Harikrishnan, S. et al. Revisiting current distribution and future habitat suitability models for the endemic Malabar Tree Toad (Pedostibes tuberculosus) using citizen science data. Sci Rep 14, 18856 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60785-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60785-1