Abstract

Comprehending the phylogeography of invasive organisms enhances our insight into their distribution dynamics, which is instrumental for the development of effective prevention and management strategies. In China, Pomacea canaliculata and Pomacea maculata are the two most widespread and damaging species of the non-native Pomacea spp.. Given this species’ rapid spread throughout country, it is urgent to investigate the genetic diversity and structure of its different geographic populations, a task undertaken in the current study using the COI and ITS1 mitochondrial and ribosomal DNA genes, respectively. The result of this study, based on a nationwide systematic survey, a collection of Pomacea spp., and the identification of cryptic species, showed that there is a degree of genetic diversity and differentiation in P. canaliculata, and that all of its variations are mainly due to differences between individuals within different geographical populations. Indeed, this species contains multiple haplotypes, but none of them form a systematic geographical population structure. Furthermore, the COI gene exhibits higher genetic diversity than the ITS1 gene. Our study further clarifies the invasive pathways and dispersal patterns of P. canaliculata in China to provide a theoretical basis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite ongoing efforts to understand the factors that influence the evolution of species, it is widely recognized that speciation is a complex process involving mutation, gene flow, natural selection, and genetic drift1. Natural selection is often considered the primary force shaping genetic diversity in species2,3,4, while neutral theories suggest that evolution is not natural selection, but rather random genetic drift5. In the last three decades, many authors have considered the neutral theory to be outdated6, but recent studies have demonstrated that short tandem repeat sequences (STRs) can bind transcription factor DNA-binding domains7. A new theory-the theory of maximum genetic diversity8 has also emerged, which retains the advantages of the neutral theory. Therefore, the present form of the neutral theory is incomplete and, despite its limited applicability, likely to remain an integral part of the exploration of molecular evolution5. The comparison of DNA sequences has become a valuable tool in studying the evolutionary forces at play9. For pests, insights into how phylogeography and populations’ evolutionary history patterns are shaped and their major associated evolutionary mechanisms are still lacking, but this is important for sustainable management and ecology and evolution studies10,11,12.

Mitochondrial DNA cytochrome c oxidase subunit I [COI] and ribosomal DNA Internal Transcribed Spacer I [ITS1] markers have been widely and successfully used to reveal the genetic structure and evolutionary biology of numerous agricultural pests, including pink rice borer13, Spodoptera frugiperda14, Arctodiaptomus dorsalis15, and Aculops lycopersici16. It is well known that ribosomal genes are commonly used in molecular phylogeny, kinship analysis, since ITS is under less natural selection pressure during the evolutionary process, more variation exists17, and the evolutionary rate of ITS fragments is 10 times higher than that of 18S rDNA. Recent studies have found that ITS1 is more efficient than ITS2, and its primers’ applicability are more general and widespread, making ITS1 superior to ITS2. The evolutionary rate of mitochondrial genes is faster18 and is more effective in revealing haplotypes and population histories than that of ribosomal genes.

The Pomacea spp., freshwater gastropod snails native to the Amazon region of South America, has spread and become a worldwide pest, owing to its extreme adaptability, very wide host range, and lack of natural enemies19,20. The Pomacea spp. are a group consisting of several species, including Pomacea canaliculata and Pomacea maculata, the primary species introduced into China. These two snails have been frequently mistaken for one species because of their morphological similarities21, and, for a long time, P. canaliculata was considered to be the only invasive snail, meaning that the two were conflated in early literature reports22. Analyses of the Pomacea spp. based on mitochondrial genes appeared in 2011, followed by the molecular identification of the Pomacea spp. using COI23,24, and genetic differentiation analyses of different populations have gradually increased in recent years25,26,27,28,29, with COI also being widely used in population history dynamics studies30,31,32. However, an analysis of the Pomacea spp. based on ribosomal genes has not been reported. Therefore, it is extremely necessary to detect the geographical distribution of the genetic structure of P. canaliculata from the perspective of various populations based on the two genes.

In China, however, knowledge of the phylogeography and evolutionary biology of Pomacea spp. is limited compared to other pests. In this study, we explored the invasive pathway and dispersal patterns of P. canaliculata through an integrated phylogeographic approach. We collected a large number of P. canaliculata specimens from almost all the damaged areas in China (20 geographic populations in total) and analyzed genetic data with mitochondrial and ribosomal DNA COI and ITS1, respectively, as deciphering the phylogeography and population evolutionary history can facilitate the development of effective pest suppression protocols and sustainable management strategies33,34. The primary objectives of this study were to: (a) evaluate the genetic diversity of P. canaliculata; (b) investigate the evolutionary history of population in China.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and DNA extraction

In 2021–2022, we collected both snails and egg of Pomacea spp. from rivers, ponds, and public farmland at 20 different sites across China, almost covering all the regions. The total DNA from the evenly sized, collected adult snails was purified using the AxyPrep Genomic DNA Kit (Suzhou, China).

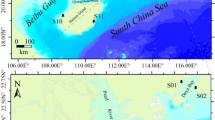

The mitochondrial and ribosomal gene sequencing

The primers for COI and ITS1 were designed using Primer5. COI was amplified using Primers(F) (5’AGAGTGGTGCTGGAACTGGATGAA3’ and 5’CCGGTGCTCTATTAGGGGATGATCAA3’) and Reverse(R) (5’GCTAATATAGCATAAATTATTCCTAAAGTACC3’). The ITS1 region was amplified using primers F (5’CGGATTGGTCTCGGCCCGCCCTTCA3’) and R (5’ATCCACCGCCTAAAGTTGTT3’) also used for the sequencing reactions. For the polymerase chain reactions (PCRs), we used 2μL DNA in the reaction mixture containing 12.5μL Taq Master Mix, 1μL of each primer, and 8.5μL ddH2O. The PCR temperature profile was the following: 94℃ for 3min, 94℃ for 1min, 55℃ for 45s, 72℃ for 1min, 35 cycles, and 72℃ for 10min. An electrophoretic analysis of the PCR fragments was performed on 1% agarose gel. The resulting PCR products were purified using a Gel DNA Extraction Kit (Vazyme) and sequenced with an ABI 3730XL DNA sequencer (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai). Using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)-Blast (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) based on the COI gene against homologous sequences in GenBank, the highest sequence homology (> 97%) was identified for P. canaliclata. The distribution of P. canaliculata was screened, with 6 uniformly sized adult snails selected at each locus for subsequent studies; the locations are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. Sequences of 18 locations were submitted to the NCBI (GenBank accession nos. PP461874-PP461981 and PP448193-PP448300).

Sampling locations of 18 P. canaliculata populations in China: map created using Arcgis platform. Abbreviations described in Table 1.

Genetic diversity analysis

We utilized CLUSTAL X 1.8335 to manually align the sequences after removing any redundant ones. Sequences were calculated for parameters such as parsimony informative sites (Pi), single mutation sites(S), variant sites(V), GC content of the sequences, reversion values(R) of the sequences, and distances within and among groups using MEGA X36,37. Genetic diversity was analyzed, including parameters such as the number of polymorphic sites(S), the total number of mutations(η)38, the number of haplotypes(H), nucleotide diversity (π), haplotype diversity (Hd)39, and the average number of nucleotide differences (K)40 using DNASP v. 5.041.

Population genetic structure analyses

We applied multiple complementary approaches to explore the population genetic structure of P. canaliculata based on both mtDNA and rDNA datasets.

Using the Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) model in the STRUCTURE v2.3.3 software42,43. We performed this analysis with K ranging from 2 to 10, a burn-in of 10,000, and a run length of 100,000, each K-value obtained with 10 independent runs. The statistic “△K”, indicating the most likely number of subpopulations, was calculated following the Evanno method44, and then the Q matrix under the highest △K-value was obtained. Next, to visualize the genetic divergence between populations, a pairwise distance matrix derived from the COI and ITS1 genes Nei’s genetic distance for all samples was calculated, and a neighbor-joining(NJ) tree was constructed using TASSEL v5.0, which was used to analyze kinship45. In addition, we utilized principal component analysis (PCA) in the R environment as a complementary method to identify the genetic structure of P. canaliculata.

F-statistics value (Fst; differentiation index), gene flow (Nm), and exact tests between the populations were calculated based on both mtDNA and rNDA datasets using the Arlequin v. 3.5 software46. and an analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA).

Haplotype relationship analysis

We constructed split networks to reveal relationships among mitochondrial haplotypes using NETWORK v. 10.2.0.047,48and performed a neighbour-net analysis under a Kimura-2-parameter (K2P) distance model after 1000 bootstraps.

Demographic history analysis

The demographic history of P. canaliculata populations in China was studied using mismatch distributions data in DNASP v. 5.041. Neutrality tests based on Tajima's D and Fu's Fs parameters were performed, with all the parameters evaluated based on 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Result

High level of genetic diversity

There were 445 base pairs in the mtDNA COI sequences, with 232 bp and 114 bp being variable and parsimony informative, respectively. For the COI genes, 30 haplotypes were identified (Supplementary Table S1 online), with 22 distinct haplotypes only present in one individual, the remaining 8 haplotypes present in at least two or more individuals, and Hap9 being the most prevalent haplotype in all populations. The majority of the mutation sites were found at position 1 (140, 136, and 135 at position 1, 2, 3), according to our analysis of the polymorphisms at each of the codon's positions (1, 2, or 3) (Supplementary Table S3 online). There were 118 single-ton variable sites. In addition, the rDNA ITS1 sequences were 469 base pairs, with 89 bp and 56 bp being, respectively, variable being parsimony informative. There were 61 haplotypes found for the ITS1 genes (Supplementary Table S2 online), of which 52 were distinct haplotypes found in just one individual, while the other 9 haplotypes were found in at least two or more individuals. Hap1 was the most common and ubiquitous haplotype across the populations. The majority of the mutation sites were found at position 3 (146, 144 and 147 at position 1, 2, 3), according to our analysis of the polymorphisms at each of the codon's positions (Supplementary Table S4 online); 33 of these were singleton variables. The genetic variance in the eighteen P. canaliculata populations in China varied, with the majority showing significant levels of variation. For the COI and ITS1 genes independently, we created haplotype-based network graphs where each node corresponded to a haplotype (Fig. 2).

In terms of COI, the average haplotype diversity (Hd) across all the populations was 0.877, with an average nucleotide diversity (π) of 0.04304 and a mean number of nucleotide differences (K) of 14.719 (Table 2). Regarding ITS1, the mean haplotype diversity (Hd) across all the populations was 0.924, with a mean nucleotide diversity (π) of 0.02336 and an average number of nucleotide differences (K) of 10.161 (Table 2). Additionally, an evaluation of the genetic diversity of P. canaliculata was conducted by excluding unique haplotypes (e.g., Hap3 and Hap5) exclusive to individual P. canaliculata. Upon the removal of these distinctive haplotypes, the average haplotype diversity (Hd) for all the populations in the COI gene dropped to 0.812. The mean nucleotide diversity (π) across all the populations was 0.03600, with an average number of nucleotide differences (K) of 14.938. Similarly, for the ITS1 gene, the average haplotype diversity (Hd) among all the populations decreased to 0.717, the mean nucleotide diversity (π) was 0.02257, and the average count of nucleotide differences (K) was 9.910. These parameters collectively indicate a substantial level of genetic diversity within P. canaliculata.

Demography history

We determined the population genetic structure of P. canaliculata based on both mtDNA and rDNA datasets.

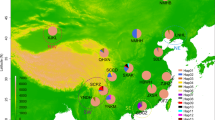

From the mtDNA data analyses, a Bayesian cluster analysis using STRUCTURE revealed an optimal value of K = 4 was the best fit for the 18 populations in China and a relatively high value of Evanno’s delta (K) (Fig. 3a). The FST value among all the geographical groups was 0.45296 (Table 3), indicating a high level of genetic differentiation among different geographic populations, alongside genetic exchange (Fig. 4a). The Exact test showed that 67.32% of the populations (Table S5 online) did not support the random mating group hypothesis (P < 0.05), suggesting that reproductive isolation has occurred between some of the geographic populations. As a result, a possible cryptic species of P. canaliculata was found based on the COI gene alone. The results of the NJ phylogenetic tree (Fig. S1a online) and PCA (Fig. 3b) were consistent with the population stratification obtained from the STRUCTURE software (Fig. 3c). Therefore, four more subgroups were identified (Fig. 3a): the first subgroup included the JSYZ, WBWH, JGZTR, GXNN, GDGZ, and HNDZ populations; the second subgroup contained the ZJHZ, JXNC, JXSR, FJFZ, and CQ populations; the third subgroup contained the JSYC, SCCD, and YNYX populations; and the fourth subgroup comprised the JSSZ, FJXM, GZGY, and ZJZJ populations.

Four P. canaliculata subgroups in China based on mtDNA data analysis. (a) Graph showing the number of inferred clusters (K) using Evanno’s delta (K) method. (b) Principal components analysis plot for P. canaliculata populations based on mtDNA genotypes; two-dimensional scales are used to reveal population stratification. (c) Four P. canaliculata subgroups in China based on STRUCTURE analysis. Abbreviations of the populations are described in Table S1online.

Heatmaps of genetic differentiation (Fst, lower left triangles) and gene flow (Nm, top right triangles) of different P. canaliculata populations in China using GraphPad Prism v8.0.2. (a) Analyzed using mtDNA COI gene. (b) Analyzed using rDNA ITS1 gene. Note: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ∞ infinity, green squares indicate Nm > 1.

From the rDNA data analyses, a Bayesian cluster analysis using STRUCTURE revealed an optimal value of K = 7 was the best fit for the 18 populations in China (Fig. 5a), and a relatively high Evanno’s delta (K) of K = 3 (Fig. 5a). Our TASSEL analyses also confirmed these three subgroups (Fig. S1b online). In the PCA, the populations from the second subgroup were located at the tips and connected the first and third subgroups (Fig. 5b). The FST value among all the geographic populations was 0.13573(Table 3), occurring primarily within populations, with the genetic variation within populations being caused by differences in the haplotypes among them. There was less genetic differentiation and more gene flow among different geographic populations (Fig. 4b), suggesting sufficient genetic exchange but some genetic differentiation between populations. The Exact test showed that 77.22% of the populations (Table S6 online) supported the random mating group hypothesis (P > 0.05), suggesting that the majority of the populations were not reproductively segregated from one another, and, therefore, there may be no cryptic P. canaliculata species found based on the ITS1 gene alone. Three more subgroups were identified (Fig. 5c): the first subgroup included the FJXM, FJFZ, JXNC, HNDZ, SCCD, GDGZ, GZGY, and GXNN populations; the second subgroup contained the JXSR, ZJZJ, ZJHZ, JSYC, JSSZ, JSYZ, GZTR, and CQ populations; and the third subgroup contained the HBWH and YNYX populations.

Three P. canaliculata subgroups in China based on rDNA data analysis. (a) Graph showing the number of inferred clusters(K) using Evanno’s delta(K) method. (b) Principal components analysis plot in the populations of 108 accessions, two-dimensional scales were used to reveal population stratification. (c) Population structure derived from STRUCTURE software. Each parallel row represents one individual and each colored segment in each column represents the percentage of the individual in the population. Abbreviations of the populations are described in Table S1 online.

Demography history

To uncover the demography history of P. canaliculata in China, neutrality tests were conducted using Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs statistics. Based on the mtDNA COI gene, the values of Tajima’s D for all the samples were positive (D = 0.12648), and Fu’s Fs statistic was positive (Fs = 3.37497) but not significant (P > 0.05). Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs statistics for the FJFZ, GZGY, GZTR, HBWH, and ZJZJ populations were 0, indicating that these 5 populations conformed to a neutral evolution model. Meanwhile, Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs statistics for the GDGZ, JSSZ, JSYZ, YNYX, and ZJHZ populations were positive but not significant(P > 0.05), which suggested that these 6 populations may have been in equilibrium or contraction (Table 4). Based on the rDNA ITS1 gene, the values of Tajima’s D for all the samples were positive (D = -0.02777), while Fu’s Fs statistic was negative (Fs = 0.76997) but not significant (P > 0.05). Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs statistics for the GXNN population were 0, indicating that conformed to a neutral evolution model. Instead, Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs statistics for the GDGZ, JSYC, JXSR, and CQ populations were negative but not significant (P > 0.05), suggesting that these four populations may have been in an expansionary phase. Finally, Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs statistics for the FJFZ, FJXM, GZTR, HNDZ, JXNC, and ZJHZ populations were positive but not significant (P > 0.05), indicating that these 6 populations may have been in equilibrium or contraction (Table 4). Based on our analysis, the multimodal mismatch distribution of all P. canaliculata samples (Fig. 6) may indicate that the P. canaliculata populations in China fit a neutral evolution model or that our samples covered several divergent populations.

Discussion

For the COI gene, the genetic distance between groups of different geographical populations was within 7.0%, and the results of the molecular variance analysis (AMOVA) showed that the Fst value was 0.45296 (P = 0.0000), the Fst statistic at the population level showed a degree of genetic differentiation among the 18 populations, that is, values greater than 0.05 (P < 0.05) and 0.25 (P < 0.05) between 71.24 and 64.71% of the populations, respectively, and less than 0.05 between 13.73% of the populations, but the difference was not significant (P > 0.05). Previously, Balloux and Lugon-Moulin49 established that Fst values greater than 0.05 indicate the presence of genetic differentiation, with larger values indicating greater genetic differentiation. As a result, the values observed in our study indicated that a very great degree of genetic differentiation had occurred among the different geographical populations, with FJFZ and GXNN populations having the largest Fst value, followed by ZJHZ, ZJZJ, GZTR, and CQ populations. And FJFZ and GXNN populations shared one haplotype, GZTR shared one haplotype with JSYC and JSYZ, ZJHZ shared one haplotype with JSSZ, meanwhile ZJZJ was in the largest haplotype with CQ. In the gene flow results, we found that YNYX had an infinite gene flow with GDGZ, JSYZ, JXNC, and SCCD populations. According to the literature, the Pomacea spp. has been introduced into Yunnan Province multiple times. It was first introduced in 1985 into Dehong Dai and the Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture from the Aquatic Research Institute of Guangzhouand, in the same year, into the Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture as a farmer enrichment project. In 1986, it was brought into Jiangyin Farm, Huangping town, Heqing County50. In 1987, it was introduced into Xiashankou, Yousou town, Eryuan County, Dali Prefecture, subsequently abandoned in the Xihu and Donghu Wetlands and the farmland ditches around Xiashankou51, and brought back into the Dehong Prefecture during a study tour in 1990 to rear two snails, subsequently entered the farmland of Cangyuan County. In 2000, the infestation was heavier in the areas around Lake Erhai52, whose large-scale invasion began in 201053,54, consistent with our results.

For the ITS1 gene, the genetic distance between groups of different geographical populations was within 2.6%, and the results of the molecular variance analysis (AMOVA) showed the Fst value was 0.13573 (P = 0.0000), the Fst values between 24.18 and 17.65% of the populations were greater than 0.05 (P < 0.05) and 0.25 (P < 0.05), respectively, which produced a large genetic differentiation between GXNN and GZGY and other geographic populations, while Fst values was 0 for the GXNN and GZGY populations. According to Li et al.55, the first appearance of the Pomacea spp. in Guizhou Province corresponded to the introduction of fish fry from Guangxi into reservoirs and ponds in Pingtang County in the early 1990s, then spreading to rivers, ditches, and farmlands, while the earliest discovery of these species in Guangxi was in the mid-1980s in Fangchenggang city, and with uncertain origins. Therefore, it can be determined that GXNN and GZGY belong to the same invasion pathway and Fst values of GZGY with JXNC, HNDZ were less than 0.05 with Fst values less than 0 for JXNC with FJFZ, FJXM, GDGZ, SCCD, and HNDZ, therefore, JXNC, FJFZ, FJXM, GDGZ, GXNN, HNDZ, and GZGY were classified into a subgroup. The genetic differentiation between JXNC and JXSR populations was small (Fst = 0.1), and the gene flow large (Nm = 4.5). In contrast, there was greater genetic differentiation between GZGY and GZTR populations (Fst = 0.36667), suggesting different invasion pathways for different geographical populations in Guizhou Province. The Fst values of GZTR and JSSZ, JSYC, and JSYZ in Jiangsu Province were all less than 0.05, and the first discovery of Pomacea spp. in Jiangsu Province was in Zhangpu Town, Kunshan City56, however, the geographical distance between the two places is 1457 km, with no way to achieving population migration by relying on the free dispersal of snails, meaning that there must have been some influence from anthropogenic activities. The results of this study also found that there may have been population expansion in GDGZ, JSYC, JXSR, and CQ, preserving the genetic diversity of P. canaliculata and increasing the possibility of colonization in new environments, and that population dispersal occurred within China.

To sum up, the results obtained based on COI and ITS1 have both similarities and differences due to the varied information they carry. The greatest genetic differentiation occurred in the GXNN population, which was first introduced into Guangdong Province, in mainland China, in 198157, and then into Guangxi and Hainan Provinces from Guangdong Province in the mid-1980s58,59, autonomously spreading to Fujian Province in 198460 In the same year, snails were introduced into Sichuan Province, and in 1987, 1988, and 2004, more specimens were introduced from different areas. In different time periods, snails were introduced from different areas into Yunnan Province61,62. At the end of the 1980s, after the introduction of overseas Pomacea specimens into Jiangxi Province due to a flood, the species spread to the whole province63. During the same period, specimens appeared in Ningbo, in Zhejiang Province, and again in the early 1990s, two introductions which we infer originated from different places64,65. In 1989 it was also introduced in Chongqing and gradually spread66, and in the early 1990s snails were introduced from Guangxi Province into Guizhou Province, where a genetically distinct geographic population (GZTR) also exists55,67. In 1998 it was introduced into Hubei Province, reintroduced in 2014, and spread by flooding in 201668,69, and artificially introduced by GZTR into Jiangsu Province in 200356. From the time of invasion and our results, we obtained that the GXNN, HNDZ, and FJ populations were introduced from Guangzhou; subsequently, SCCD, YNYX, JX, ZJ, and CQ populations were introduced from different regions, and through environmental influences and active dispersal, several populations at different times underwent sufficient genetic exchange.

The results obtained from different genes were analyzed, and it was found that the evolutionary rate based on COI gene was faster and carried more information; the Fst was greater than that obtained by ITS1; and the number of mutation sites (V = 232 and V = 89, respectively) single mutation sites (S = 118 and S = 33, respectively) was larger. A total of 30 haplotypes were based on COI, while 61 were based on ITS1. Although the haplotype diversity of COI gene (Hd = 0.877, P < 0.05) was less than that of ITS1 gene (Hd = 0.924, P < 0.05), the nucleotide diversity of COI (Pi = 0.04304, P < 0.01) was greater than that of ITS1 gene (Pi = 0.02336, P < 0.01). The Exact tests for the COI gene revealed the possible existence of a cryptic P. canaliculata species, which is consistent with the result of Lv et al.70 and Yang et al.71, who named this cryptic species as Pomacea occulta72, whereas Exact tests for ITS1 gene did not support its existence. Further indicating that the information carried by the two genes is different and that mitochondrial DNA evolves at a faster rate.

Overall, COI can better reflect the origin, migration, and dispersal of a species in a certain geographic region and be used for the study of population history and dynamics, genealogical geography, genetic diversity, and phylogenetic classification, among other topics. More than 40 years have passed since the introduction of the Pomacea spp. to mainland China, and its genetic richness should be relatively evenly represented in its various populations rather than being concentrated in one or a few specific populations, which is in line with the following findings that the genetic diversity of P. canaliculata is relatively high in the populations in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River in China32, in Zhejiang Province27, in Suzhou City28, and in Nanchong City29 populations, all of the P. canaliculata populations showed high genetic diversity, and the Chinese population of P. canaliculata was closer to the Argentinean population71, and multiple invasions occurred in the different populations, which could obtain more genotypes from the original gene pool, thus facilitating the P. canaliculata population adaptation and expansion73. We hypothesized that the evolutionary history the Pomacea spp. in China may have also been complexly influenced by some abiotic (e.g., climate) and biotic components (e.g., host plants). We need more studies, both theoretical and experimental, to reach a full understanding of evolution and variation at the molecular level of this specie.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in NCBI: GenBank accession nos. PP461874-PP461981 and GenBank accession nos. PP448193-PP448300.

References

Zhan, J. & Mcdonald, B. A. The interaction among evolutionary forces in the pathogenic fungus Mycosphaerella graminicola. Fungal Genet Biol. 41, 590–599 (2004).

Darwin, C. The origin of species by means of natural selection. (Murray, 1859).

Turesson, G. The genotypical response of the plant species to the habitat. Hereditas. 3, 211–350 (1922).

Primack, R. B. & Kang, H. Measuring fitness and selection in wild plant populations. Annu Rev Eco Syst. 20, 367–396 (1989).

Kreitman, M. The neutral theory is dead. Long live the neutral theory. Bioessays. 18(8), 678–683 (1996).

Kern, A. D. & Hahn, M. W. The neutral theory in light of natural selection. Mol Biol Evol. 35(6), 1366–1371 (2018).

Horton, C. A. et al. Short tandem repeats bind transcription factors to tune eukaryotic gene expression. Science. 381(6664), eadd1250 (2023).

Huang, S. New thoughts on an old riddle: What determines genetic diversity within and between species?. Genomics. 108(1), 3–10 (2016).

Ramos-Onsins, S. E. & Rozas, J. Statistical properties of new neutrality tests against population growth. Mol Biol Evol. 19(12), 2092–2100 (2002).

Leffler, E. M. et al. Revisiting an old riddle: What determines genetic diversity levels within species?. PLoS Biol. 10(9), e1001388 (2012).

Wei, S. J. et al. Genetic structure and demographic history reveal migration of the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) from the southern to northern regions of China. PLoS One. 8, e59654 (2013).

Gao, F., Zou, W., Xie, L. & Zhan, J. Adaptive evolution and demographic history contribute to the divergent population genetic structure of potato virus Y between China and Japan. Evol Appl. 10, 379–390 (2017).

Tang, X. T., Lu, M. X. & Du, Y. Z. Molecular phylogeography and evolutionary history of the pink rice borer (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae): Implications for refugia identification and pest management. Syst. Entomol. 1–13 (2022).

Samanta, S. et al. Evidence of population expansion and insecticide resistance mechanism in invasive fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda). BMC Biotechnol. 23, 17 (2023).

Guinto, S. K. P., Machida, R. J. & Papa, R. D. S. Insights on the connectivity, genetic diversity, and population structure of Arctodiaptomus dorsalis (Marsh, 1907) (Copepoda: Calanoida: Diaptomidae) in the Philippines. J Crustacean Biol. 43(4), 70 (2023).

Duarte, M. E., Lewandowski, M., de Mendonca, R. S., Simoni, S. & Navia, D. Genetic analysis of the tomato russet mite provides evidence of oligophagy and a widespread pestiferous haplotype. Exp Appl Acarol. 89, 171–199 (2023).

Lv, J. et al. Assessment of four DNA fragments (COI, 16S rDNA, ITS2, 12S rDNA) for species identification of the Ixodida (Acari: Ixodida). Parasit Vectors. 7, 93 (2014).

Pérez-Portela, R. et al. Genetic homogeneity of the invasive lionfish across the Northwestern Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico based on Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Sci Rep. 8(1), 5062 (2018).

Cowie, R. H. Apple snails (Ampullariidae) as agricultural pests: their biology, impacts and management. CABI Publishing. 145–192 (2002).

Hayes, K. A., Joshi, R. C., Thiengo, S. C. & Cowie, R. H. Out of South America: Multiple origins of non-native apple snails in Asia. Divers Distrib. 14(4), 701–712 (2010).

Hayes, K. A., Cowie, R. H., Thiengo, S. C. & Strong, E. E. Comparing apples with apples: clarifying the identities of two highly invasive Neotropical Ampullariidae (Caenogastropoda). Zool J Linn Soc-Lond. 166(4), 723–753 (2012).

Carlsson, N. O. L. & Lacoursière, J. O. Herbivory on aquatic vascular plants by the introduced golden apple snail (Pomacea canaliculata) in Lao PDR. Biol Invasions 7(2), 233–241 (2005).

Yang, Q. Q., Liu, S. W., Ru, W. D., Liu, G. F. & Yu, X. P. Molecular identification of invasive golden apple snails in Zhejiang Province based on DNA barcoding. Biodivers. Sci. 24(3), 341–350 (2016).

Ramirez, R. et al. Do not judge a snail by its shell: molecular identification of Pomacea species (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae), with particular reference to the Peruvian Amazonian giant apple snail, erroneously synonymized with Pomacea maculata. Archiv fur Molluskenkunde. 151(1), 7–17 (2022).

Tran, C. T., Hayes, K. A. & Cowie, R. H. Lack of mitochondrial DNA diversity in invasive apple snails (Ampullariidae) in Hawaii. Malacologia 50(1–2), 351–357 (2008).

Rama, R. S., Liew, T. S., Yow, Y. Y. & Ratnayeke, S. Cryptic diversity: Two morphologically similar species of invasive apple snail in Peninsular Malaysia. PLoS ONE. 13(5), e0196582 (2018).

Huang, Y., Yue, Z. Y., Mao, G. Y., Guo, Y. H. & Zhang, Y. Population genetics of invasive Pomacea spp. in Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province. Chin. J. Schisto Control. 32(1), 23–27 (2020).

Qian, Z. J. et al. Genetic diversity of invasive Pomacea snails in Suzhou City. Chinese Journal of zoology. 56(6), 929–938 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Analysis on the Species and Genetic Diversity of Pomacea in Nanchong. J. China West Normal Univ. (Natural Sciences). 1–8 (2023).

Yang, Q. Q., Liu, S. W., He, C. & Yu, X. P. Distribution and the origin of invasive apple snails, pomacea canaliculata and p. maculata (gastropoda: ampullariidae) in China. Sci Rep. 8(1), 1185 (2018).

Liu, Y.M. et al. The global distribution of apple snail [Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck, 1819)]. Hubei Agricultural Sciences. 58(6), 70–72+77 (2019).

Pu, J. J. et al. Species identification and population genetic structure of non-native apple snails (Ampullariidea: Pomacea) in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Biodivers. Sci. 31(3), 117–130 (2023).

Guillemaud, T., Ciosi, M., Lombaert, E. & Estoup, A. Biological invasions in agricultural settings: Insights from evolutionary biology and population genetics. CR Biol. 334, 237–246 (2011).

Meng, L., Wang, Y., Wei, W. H. & Zhang, H. Population genetic structure of Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Liviidae): Host-driven genetic differentiation in China. Sci Rep. 8, 1473 (2018).

Chenna, R. et al. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3497–3500 (2003).

Kimura, M. A. Simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 16, 111–120 (1980).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. MB E. 35, 1547–1549 (2018).

Watterson, G. A. On the number of segregating sites in genetical models without recombination. Theor Popul Biol. 7, 256–276 (1975).

Nei, M. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics. (New York, 1987).

Tajima, F. Evolutionary relationship of DNA sequences in finite populations. Genetics. 105, 437–460 (1983).

Librado, P. & Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 25, 1451–1452 (2009).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 155, 945–959 (2000).

Falush, D., Stephens, M. & Pritchard, J. K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 164, 1567–1587 (2003).

Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620 (2005).

Bradbury, P. J. et al. Tassel: Software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. 23, 2633–2635 (2007).

Excoffier, L. & Lischer, H.E. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10(3), 564–567 (2010).

Forster, P., Toth, A. & Bandelt, H. J. Evolutionary networks of word lists: Visualising the relationships between Alpine Romance languages. J Quant Linguist. 5(3), 174–187 (1998).

Bandelt, H. J., Forster, P. & Röhl, A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 16, 37–48 (1999).

Balloux, F. & Lugon-Moulin, N. The estimation of population differentiation with microsatellite markers. Mol Eco. 11(2), 155–165 (2002).

Wang, M. H. & Yang, Y. Z. Current situation of pomacea and opinions on prevention and control in Huangping Town. YunNan Agriculture. 4, 47 (2011).

Dali Agricultural Environment Station. Distribution of the invasive alien organism Pomacea in Dali Prefecture. http://www.ynagri.gov.cn/dl/news618/20101104/639412.shtml (2010).

Yan, J. G., Ma, X. B., Wang, L. Q. & Xiao, W. The distribution of Ampullaria gigas Spix in the Erhai Region. J. Dali Univ. 8(4), 67–69 (2009).

Su, X. J. et al. Investigation on the distribution of Pomacea canaliculata in Erhai Lake Basin. J. Dali Univ. 1(6), 57–61 (2016).

Deng, X. L. et al. Temporal and spatial distribution of Pomacea canaliculata in Er’hai Lake Catchment. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 13(4), 134–142 (2018).

Li, Y. S., Zeng, Y. L., Xiang, Z. Q., Wu, Q. & Yang, W. Occurrence and control measures of Pomacea in paddy fields in Pingtang County. Farm. Cultivat. 4, 59 (2004).

Li, Q.Y., Lou, L.J., Zhou, B. & Huang, Z. Occurrence, prevention and control of pomacea in paddy field. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 3, 134+137 (2020).

Chen, Z. D. Occurrence and control of apple snails in Lufeng County. Plant Protection. 17(6), 48–49 (1991).

Jiang, W. B. & Yang, G. M. The tendency of occurrence of Ampullarial gigas Spix and prevent & control countermeasures. J. Guang xi Agric. 21(5), 23–25+34 (2006).

Su, B. M., Liu, Z. F., Chen, J. X. & Zhang, J. E. Survey of invasion and prevention and control measures of Pomacea canaliculata in Hainan. J. Trop. Biol. 7(2), 167–170 (2016).

Zhang, S.L. & Jiang, D.S. Occurrence of apple snail in Fuding City and its management. Anhui Agron. Bull. 14(20), 100+119 (2008).

Wu, Z. P. et al. Preliminary study on the occurrence and prevention and eradication of the apple snail in Sichuan province. Plant Quarantine. 9(5), 266–269 (1995).

Tao, H. Q., Jia, B. Y., Zhang, F. Y. & Wang, X. C. Investigation on Exotic Species Ampullaria gigas in Chengdu and analysis of control measures. Sichuan Environ. 24(3), 108–110 (2005).

Xiong, S. Y. & Zheng, M. Preliminary investigation on the occurrence of apple snail in Guangchang and other places, and preventive and control measures. Jiangxi Plant Protection. 29(2), 79–80 (2006).

Xu, L. Y. et al. Study on the occurrence and prevention of Pomacea in Ningbo city, China. Agric. Exten. 24(10), 37–38 (2008).

Li, J.J., Wu, L.G., Xu, Y.L. & Liu, G.L. Biological characteristics testing of fusiliers in farmland of Yinzhou District. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 14(22), 89+96 (2008).

Zhang, Y. J. A preliminary study on the occurrence pattern of apple snail in Rongchang County and its control measures. China Rural Well-being Sci. Technol. 6, 42–44 (2006).

Huang, S. Z. & Wang, T. X. A preliminary report on the biological characteristics of the Pomacea in Yuping County, Guizhou Province. Beijing Agric. 14, 219 (2015).

Wan, P. et al. Study on occurrence, damage and control of golden Apple Snail, Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck), in Paddy Fields of Hubei Province. Hubei Agric. Sci. 49(12), 3072–3075 (2010).

Si, S. Y. et al. New pests of aquatic vegetables in Wuhan-Pomacea canaliculata. J. Changjiang Veg. 17, 57–58 (2020).

Lv, S., Zhang, Y., Liu, H. X., Ling, H. & Utzinger, J. Phylogenetic evidence for multiple and secondary introductions of invasive snails: Pomacea species in the People’s Republic of China. Divers Distrib. 19, 147–156 (2013).

Yang Q.Q., Liu S.W., He C. & Yu X.P. Distribution and the origin of invasive apple snails, Pomacea canaliculata and P. maculata (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae) in China. Sci Rep. 8, 1185 (2018).

Yang, Q. Q. & Yu, X. P. A new species of apple snail in the genus pomacea (Gastropoda: Caenogastropoda: Ampullariidae). Zool Stud. 58, 13 (2019).

VanWallendael, A., Alvarez, M. & Franks, S. J. Patterns of population genomic diversity in the invasive Japanese knotweed species complex. Am J Bot. 108, 857–868 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank colleagues of the Plant Protection, Hainan university, Guangxi academy of agricultural sciences, Southwest forestry university, Shangrao middle school, Hunan agricultural university, Guizhou academy of agricultural sciences, Zhejiang A&F university, Southwest university, Sichuan academy of agricultural sciences, South China agricultural university, Huazhong agricultural university, Fujian agricultural and forestry university and Jiangxi academy of agricultural sciences for collecting Pomacea spp. samples. This study was supported by Nanjing Public Welfare Service System Project in 2022: Research and Application of Monitoring and Control techniques for Pomacea spp., Special Finance Project of Pukou District of Nanjing city, and the postgraduate research & practice innovation program of Jiangsu province (KYCX21_3213).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data analysis: R.W., C.D.W. and Y.W.C; investigation: R.W., C.D.W., Y.W.C., H.F.X., D.R.Y., W.R.G. and Y.Z.D.; writing-original draft preparation: R.W., C.D.W. and Y.W.C.; writing-review and editing: Y.Z.D., H.F.X., D.R.Y. and W.R.G.; funding acquisition: C.D.W., H.F.X., D.R.Y., W.R.G. and Y.Z.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, R., Chang, YW., Xie, HF. et al. Population genetic structure of Pomacea canaliculata in China based on the COI and ITS1 genes. Sci Rep 14, 12045 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62554-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62554-6