Abstract

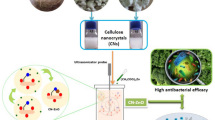

Herbal medicine combined with nanoparticles has caught much interest in clinical dental practice, yet the incorporation of chitosan with Salvadora persica (S. persica) extract as an oral care product has not been explored. The aim of this study was to evaluate the combined effectiveness of Salvadora persica(S. persica) and Chitosan nanoparticles (ChNPs) against oropharyngeal microorganisms. Agar well diffusion, minimum inhibitory concentration, and minimal lethal concentration assays were used to assess the antimicrobial activity of different concentrations of ethanolic extracts of S. persica and ChNPs against selected fungal strains, Gram-positive, and Gram-negative bacteria. A mixture of 10% S. persica and 0.5% ChNPs was prepared (SChNPs) and its synergistic effect against the tested microbes was evaluated. Furthermore, the strain that was considered most sensitive was subjected to a 24-h treatment with SChNPs mixture; and examined using SEM, FT-IR and GC–MS analysis. S. persica extract and ChNPs exhibited concentration-dependent antimicrobial activities against all tested strains. S. persica extract and ChNPs at 10% were most effective against S. pneumoni, K. pneumoni, and C. albicans. SEM images confirmed the synergistic effect of the SChNPs mixture, revealing S. pneumonia cells with increased irregularity and higher cell lysis compared to the individual solutions. GC–MS and FT-IR analysis of SChNPs showed many active antimicrobial phytocompounds and some additional peaks, respectively. The synergy of the mixture of SChNPs in the form of mouth-rinsing solutions can be a promising approach for the control of oropharyngeal microbes that are implicated in viral secondary bacterial infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mouth is the main gateway to the body and contains a highly diverse microbiota, most of which are commensal. Under normal conditions, the microbiota is able to migrate from the oral cavity to the lungs; hence, the lungs are enriched with oral taxa1. El-Solh et al.2 demonstrated that respiratory pathogens from the lung of institutionalized elder patients requiring mechanical ventilation are often genetically indistinguishable from strains isolated from the oral cavity. Co-infections caused by bacteria or fungi in several influenza virus pandemics have increased nowadays, and bacterial complications have increased the morbidity and mortality of viral infections, including Covid-193.

S. pneumoniae was isolated in almost 50% of the cases of hospital-acquired pneumonia4. It is the most common bacteria found in viral secondary bacterial infections and is mostly associated with high mortality and morbidity during influenza epidemics and pandemics5. A recent investigation demonstrated that poor oral hygiene was linked to an increase in the number of obligate anaerobes located in the pneumonia-affected lungs of the studied patient population6. Professional oral hygiene measures decrease the number of oral bacteria7, reduce the number of days of fever, inhibit the development of pneumonia8, reduce the frequency of nosocomial pneumonia by nearly 40%9, and reduce the mortality rate caused by pneumonia10. Several other oral care practices have been attempted, including tooth brushing and mouthwashes. Gargling is considered to have promising effects through the removal of oral/pharyngeal proteases that help viral replication11.

Salvadora persica (S. persica), locally called miswak, is a traditional toothbrush that belongs to the Salvadoraceae family and has demonstrated antimicrobial properties against bacteria, viruses, and fungi12,13,14. The anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects of S. persica extracts on cariogenic and periodontal pathogens led to their incorporation into oral hygiene products such as mouthwashes and toothpastes15. Almaghrabi16 demonstrated strong activity of extracts obtained from fruits, twigs, and roots of S. persica against S. pneumoniae wild-type strains. Recent findings showed that S. persica extract decreased the amount of oral pathogen colonization in mechanically ventilated patients17.

In recent years, nanotechnology has emerged as an interdisciplinary field undergoing rapid development as a powerful tool for various biomedical applications, especially as antimicrobial agents18. Many oral care products, especially mouthwash and toothpastes, contain nanoparticles with anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory, and remineralizing properties19 have been investigated in dental applications. Among the various existing nanomaterials, chitosan nanoparticles (ChNPs) showed excellent antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal properties20.

Combining S. persica extract with ChNPs is a novel approach with the intent of producing a synergistic antimicrobial effect against a wide range of microorganisms. Since there is evidence suggesting a close relationship between ventilator-associated pneumonia and the microbial profile present in the oral cavity21, this combination might be used as a preventive measure to control potentially harmful oropharyngeal microorganisms, as well as a therapeutic agent for established infections.

The incorporation of ChNPs with S. persica extract as an oral care product has not been extensively explored. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the antimicrobial efficacy of the ethanolic S. persica extract and ChNPs mixture against oropharyngeal microorganisms.

Materials and methods

Salvadora persica extract preparation

The plant collection and use were in accordance with all the relevant guidelines. S. persica root sticks were obtained from the Jazan region of Saudi Arabia. The sticks were cut into small pieces and milled by an electric grinder. Fifty grams of S. persica powder were extracted by soaking in 500 mL of 70% ethanol on a shaker at room temperature for 24 h. The extract solutions were then filtered using Whatman No. 4 filter paper and transferred to a porcelain dish to evaporate at 40 °C. The solutions were completely evaporated, and the powdered extract was stored in a refrigerator (4 °C) until required.

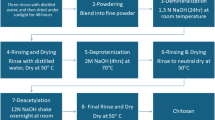

Chitosan nanoparticles (ChNPs)

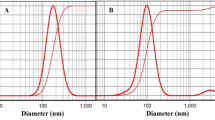

Chitosan nanoparticles were purchased from Nanoshel-UK Ltd. and prepared using the ionic gelation method. Different concentrations of chitosan (0.1 to 0.5 g) were added to 100 mL of 1% l-ascorbic acid and mixed well using a magnetic stirrer.

Microbial strain and inoculum preparation

Gram-positive strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumonia ATCC 49136), Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans ATCC 25175), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus ATCC 25923); gram-negative strains of Klebsiella pneumonia (K. pneumonia ATCC 700603), Escherichia coli (E. coli ATCC 35218), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853); and fungal strains of Candida albicans (C. albicans ATCC 14053) and Candida krusei (C. krusei ATCC 14243) were included in the study. All test strains were provided by the Central Research Laboratory-Female Campus and the lab of Biotechnology, College of Pharmacy-King Saud University.

The microbial strain was cultured on freshly prepared tryptic soy broth (TSB) (OXOID, Hampshire, England) for 18 h at 36 ± 1 °C to an exponential phase. Streptococcus species were additionally cultured on Brain Heart Infusion Broth (BHIB) (Difco, Laboratories, Detroit, MI) with 5% CO2 and incubated at 35 ± 1 °C. The optical density (OD 620) of the microbial mass was detected by determining the turbidity of the bacterial growth using a spectrophotometer. The inoculum density was adjusted using normal saline to produce a final count of 1.5 × 106 CFU/mL. The stock solution of S. persica extract was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to achieve a final concentration of 512 mg/mL.

Antimicrobial testing

The antimicrobial activity of different concentrations (25, 50, and 100 mg/mL) of S. persica extract and ChNPs was evaluated using standard agar well diffusion with Streptomycin (30 μg) and Amphotericin B (10 μg) discs (Oxoid, UK) serving as positive controls against bacterial and fungal strains, respectively, while ethanol and propylene glycol solution served as a negative controls for S. persica extract and ChNPs, respectively. All experiments were conducted in triplets.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was performed by a standard twofold broth dilution method. Chlorohexidine (CHX) and fluconazole (FLZ) were used as positive controls. All experiments were conducted in triplicate for each extract. The MIC was the lowest concentration of antimicrobial agent that inhibited observable microbial growth.

Minimum lethal concentration (MLC) was preformed using the standard microdilution method. The MLC was detected as the lowest concentration of S. persica extract or ChNPs that did not allow visible growth (99.9% killing) on the agar plates after the incubation period. All procedures and microbiological manipulations were carried out in a Class II biological safety cabinet.

Antimicrobial evaluation of 10% S. persica and 0.5% ChNPs mixture (SChNPs)

Based on the findings of antimicrobial tests, the most effective antimicrobial concentration of S. persica (100 mg/mL = 10%) and the maximum concentration of ChNPs (5 mg/mL = 0.5%) that provide better viscosity have been used to prepare the SChNPs mixture using three formulae and evaluated against all the test strains. Propylene glycol was added as a solvent for the hydroalcoholic extract of S. persica, and l-ascorbic acid was added to acidify the medium to make it suitable for the solubility of ChNPs. In addition, l-ascorbic acid acts as an antioxidant to protect the preparation contents against oxidation (Table 1).

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) evaluation

The most sensitive bacteria (S. pneumonia) was exposed to S. persica, ChNPs, and SChNPs mixture for 24 h. S. pneumonia grown without an extract was taken as a control. After incubation, cells were centrifuged at 5000 r/min for 10 min. The pellets were washed with sterile PBS and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde for 4 h at 4 °C with an intermittent vortex. The cell biomass was fixed to a glass coverslip, and morphological changes in the cell wall were viewed under SEM (JEOL SEM, Filed Emission 7610F).

Fourier-transformed infrared (FTIR)

FTIR spectroscopy (FT-IR, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, United States) was used to identify the functional groups presented in the S. persica extract, ChNPs, and the SChNPs mixture. FTIR was measured in the range of 4000–500 cm−1.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS)

The phytochemical analysis of S. persica extract and the SChNPs mixture was accomplished on GC–MS equipment (PerkinElmer/Clarus500, United States).

Statistical analysis

Results were documented using Microsoft Excel 365, and computations were run three times. The mean and standard deviation are calculated based on the results. The MICs were computed using the SPSS software program, 2001 (version 15.0, Chigao, IL, USA). The antimicrobial efficacy of the different tested compounds was examined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Antimicrobial testing

The findings showed the antimicrobial activity of S. persica extract and ChNPs (Fig. 1), this activity was concentration dependent. S. persica extract at 100 mg/mL was the most effective against all tested strains. The highest inhibition was observed against S. pneumonia and S. mutans. Overall, S. persica demonstrated more pronounced antimicrobial activity (inhibition zones ranged from 12.8 to 2.0 mm) against gram-positive strains (S. pneumonia, S. mutans, and S. aureus) than gram-negative strains (K. pneumonia, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli), where the inhibition zones ranged from 9.6 to 1.1 mm. In addition, S. persica extracts were effective against both tested candida species. The inhibition zones ranged from 9.3 to 1.6 mm in accordance with the S. persica concentration. With the 100 mg/mL concentration, C. albicans was most susceptible, followed by C. krusei (Table 2a).

ChNPs at 100 mg/mL were the most effective concentration against all tested microbial strains. The highest inhibition was observed against S. pneumonia, E. coli, K. pneumonia, and both strains of fungi. Overall, ChNPs demonstrated pronounced antimicrobial activity, with inhibition zones ranging from 11.2 to 5.8 mm against gram-positive strains and gram-negative strains. A similar inhibition zone (11.5–6.9 mm) was observed against both tested candida species (Table 2b).

The findings of MIC and MLC showed that S. pneumonia and both fungal strains were the most sensitive to the S. persica extract (6 and 12.5 mg/ml) and ChNPs (25 and 50 mg/ml), respectively (Table 2c).

The antimicrobial efficacy of the mixture (SChNPs) of 10% S. persica and 0.5% ChNPs against tested bacterial and fungal strains is presented in Table (2d). In all tested strains, the prepared mixture showed a significant zone of inhibition with a clear decrease in MIC. The range of the MIC was determined between 4 and 32 mg/mL. The maximum reduction was observed with S. mutans and S. pneumonia at 4 and 8 mg/mL, respectively. Additionally, it displayed good activity against S. aureus and E. coli, with MIC values of 16 mg/mL. Moreover, it exhibits good efficacy against K. pneumonia and P. aeruginosa, with MIC values of 32 mg/mL. The SChNPs mixture also showed equivalently high activity against both fungal strains tested (C. albicans and C. krusei), with MIC values of 8 mg/mL.

Scanning electron microscope evaluation

Scanning electron microscopy images of S. pneumonia treated with SChNPs showed some morphological changes as compared to the control (untreated S. pneumonia cells). Normal S. pneumonia cells were smooth, intact, and regular cocci (Fig. 2a), while ChNP-treated S. pneumonia showed slight irregularity in shape and aggregation (Fig. 2b). S. persica-treated cells showed minute irregularities in shape and clustering (Fig. 2c). Whereas SChNPs-treated cells showed remarkable morphological changes like blebs and destructed cells (Fig. 2d).

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

The FT-IR spectra peak of S. persica, ChNPs, and the SChNPs mixture are shown in Fig. 3a–c, and their probable functional groups are presented in Table 3. The spectrum shows many biologically active functional groups. FTIR spectrum results show the presence of aldehydes, alkenes, carboxyl nitrogen-containing group, aromatic primary amines, sulfoxides, amines, esters, ethers, and alcohols in both samples. However, some additional bands for ketones, carboxylic acids, and benzenes were observed in the SChNPs mixture. These functional groups mainly belong to many secondary metabolites such as phenols, alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, terpenoids, and polyphenol.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

GC–MS chromatogram analysis of S. persica, and the SChNPs mixture is shown in Fig. 4 (a and b). Table 4a and b represent the list of major compounds identified by their retention time, molecular formula, and molecular weight.

Discussion

Nowadays, many plant-derived herbal medicines are being used in oral health care, mainly as antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic agents. Mouthwashes derived from medicinal plants have shown promising results in plaque and gum diseases due to the presence of active ingredients with antioxidant properties22. In this study, the ethanolic extracts of S. persica exhibited concentration-dependent antimicrobial activities against all tested strains, and the highest inhibition was observed against S. pneumonia and S. mutans. Several reports have also found extracts of S. persica to be effective antimicrobial agent23. Overall, the tested ethanolic extract demonstrated more pronounced antimicrobial activity against gram-positive strains than gram-negative strains. This difference is probably caused by the bacterial cell walls having different chemical compositions, especially in the outer membrane of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) structure24. LPS are large molecules consisting of a lipid and a polysaccharide that create a barrier to diffusion, making gram-negative bacteria more resistant to antimicrobials.

Nano-based dental materials are increasingly used clinically for oral hygiene due to their antimicrobial activity19. Chitosan is used in many commercial and dental products, such as toothpaste, enamel repair materials, dental restorative materials, coatings on implants, and adhesives25.

In this study, the antimicrobial activity of the SChNPs mixture, consisting of 10% S. persica ethanolic extract, 0.5% ChNPS, 1% l-Ascorbic acid, and 10% propylene glycol, was evaluated against the previously mentioned standard strains, and a synergistic effect was observed through the widening of the inhibition zone. The presence of different bioactive phytochemical compounds in the SChNPs mixture accounted for the broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities. As a result of the existence of bioactive compounds like alkaloids, tannins, flavonoids, phenols, terpenoids, and anthraquinones in the SChNPs mixture, broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities were detected. There are several possible mechanisms for how some secondary metabolites act against microorganisms: alkaloids may disrupt cellular walls and/or inhibit DNA replication26; tannins may deactivate microbial adhesions, enzymes, and transport proteins in cellular envelopes27; flavonoids may inhibit the synthesis of nucleic acids and energy metabolism of microbial cell membranes28; phenolic compounds and terpenoids may disrupt the microbial cell membranes29; anthraquinones act by increasing the superoxide anion levels and increasing the amount of oxygen molecules30. The antimicrobial properties of chitosan are believed to function through binding to negatively charged bacterial cell walls, altering membrane permeability, followed by attachment to DNA, inhibiting DNA replication, and finally causing cell death31.

The MLC/MIC ratio for the SChNPs mixture was determined to define whether the pharmaceutical formula was bacteriostatic or lethal in the tested samples. It is generally considered that a MLC/MIC ratio over 4 equates to bacteriostatic effects, while lesser values indicate lethal effects32. Consequently, the SChNPs mixture showed lethal efficacy against S. mutans, S. pneumonia, C. albicans, and C. krusei ; but bacteriostatic effects on S. aureus, E. coli, K. pneumonia, and P. aeruginosa.

The effects of S. persica extract and ChNPs on the surface morphology of S. pneumonia were examined by SEM. No morphological changes were observed in untreated S. pneumoniae cells with clear cell wall structure; however, the results showed a special trend of changes in cells treated with S. persica extracts, ChNPs, and the SChNPs mixture. S. pneumonia cells treated with the mixture of 10% S. persica and 0.5% ChNPs exhibited a more irregular cell shape and a high degree of cell lysis as compared to the individual solution. These results explained the synergistic effect through induced morphologic alterations by the damaging bacterial membrane and leaked cytoplasmic material. SEM results are well explained by the occurrence of many active phytocompounds, which were detected by GC–MS analysis. Many studies have reported the antimicrobial activity of these active compounds, such as tetradecanoic acid, pentadecanoic acid, n-Nonadecanol-133, 6-Octadecenoic acid , l-(+)-Ascorbic acid 2,6-dihexadecanoate34, Eicosanoic acid ,1-Nonadecene, 9-Octadecenoic acid35, which were not detected in S. persica extract alone. These results support the SEM findings that the SChNPs mixture induces maximum damage to the bacterial cells. The biological activity of any compound is influenced by its functional groups, which aid in evaluating the structure–function relationship of the bio-organic compound. FT–IR spectral analysis showed some additional peaks in the SChNPs mixture that were not detected in S. persica extract. FTIR analysis plays a crucial role in identifying and quantifying plant substances such as cell wall components, proteins, and lipids, aiding in understanding biochemical changes in samples. Changes in band height suggest modifications in chemical groups within lipids, carbohydrates, proteins, and cell wall regions36,37.

Conclusion

Across all studied strains, the prepared mixture of 10% S. persica and 0.5% ChNPs (SChNPs) demonstrated a large zone of inhibition with a distinct decrease in MIC, indicating its synergistic effect. The use of SChNPs mixture as a mouthwash can act synergistically to control oropharyngeal microbes that are implicated in secondary micorbial infections associated with primary viral infections.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Segal, L. N. et al. Enrichment of the lung microbiome with oral taxa is associated with lung inflammation of a Th17 phenotype. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 1–11 (2016).

El-Solh, A. A. et al. Colonization of dental plaques: A reservoir of respiratory pathogens for hospital-acquired pneumonia in institutionalized elders. Chest 126, 1575–1582 (2004).

Bao, L. et al. Oral microbiome and SARS-CoV-2: Beware of lung co-infection. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1840 (2020).

Sharma, S., Maycher, B. & Eschun, G. Radiological imaging in pneumonia: Recent innovations. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 13, 159–169 (2007).

Brundage, J. F. Interactions between influenza and bacterial respiratory pathogens: Implications for pandemic preparedness. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6, 303–312 (2006).

Hata, R. et al. Poor oral hygiene is associated with the detection of obligate anaerobes in pneumonia. J. Periodontol. 91, 65–73 (2020).

Ishikawa, A., Yoneyama, T., Hirota, K., Miyake, Y. & Miyatake, K. Professional oral health care reduces the number of oropharyngeal bacteria. J. Dent. Res. 87, 594–598 (2008).

Yoneyama, T., Yoshida, M., Matsui, T. & Sasaki, H. Oral care and pneumonia. The Lancet 354, 515 (1999).

Sona, C. S. et al. The impact of a simple, low-cost oral care protocol on ventilator-associated pneumonia rates in a surgical intensive care unit. J. Intensive Care Med. 24, 54–62 (2009).

Yoneyama, T. et al. Oral care reduces pneumonia in older patients in nursing homes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 50, 430–433 (2002).

Kitamura, T. et al. Can we prevent influenza-like illnesses by gargling?. Intern. Med. 46, 1623–1624 (2007).

Noumi, E., Snoussi, M., Hajlaoui, H., Valentin, E. & Bakhrouf, A. Antifungal properties of Salvadora persica and Juglans regia L. extracts against oral Candida strains. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29, 81–88 (2010).

Sofrata, A. H., Claesson, R. L., Lingström, P. K. & Gustafsson, A. K. Strong antimicrobial effect of miswak against oral microorganisms associated with periodontitis and caries. J. Periodontol. 79, 1474–1479 (2008).

Taha, M. Y. Antiviral effect of ethanolic extract of Salvadora persica (Siwak) on herpes simplex virus infection. Al-Rafidain Dent. J. 8, 50–55 (2007).

Niazi, F., Naseem, M., Khurshid, Z., Zafar, M. S. & Almas, K. Role of Salvadora persica chewing stick (miswak): A natural toothbrush for holistic oral health. Eur. J. Dent. 10, 301–308 (2016).

Almaghrabi, M. K. Antimicrobial activity of Salvadora persica on Streptococcus pneumoniae. Biomed. Res. 29, 3635–3637 (2018).

Landu, N., Sjattar, E. L., Massi, M. N. & Yusuf, S. The effectiveness of Salvadora persica stick on the colonization of oral pathogens in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit (ICU): A pilot study. Enferm. Clínica 30, 327–331 (2020).

Yeh, Y.-C., Huang, T.-H., Yang, S.-C., Chen, C.-C. & Fang, J.-Y. Nano-based drug delivery or targeting to eradicate bacteria for infection mitigation: A review of recent advances. Front. Chem. 8, 286 (2020).

Carrouel, F., Viennot, S., Ottolenghi, L., Gaillard, C. & Bourgeois, D. Nanoparticles as anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory, and remineralizing agents in oral care cosmetics: A review of the current situation. Nanomaterials 10, 140 (2020).

Rabea, E. I., Badawy, M.E.-T., Stevens, C. V., Smagghe, G. & Steurbaut, W. Chitosan as antimicrobial agent: applications and mode of action. Biomacromolecules 4, 1457–1465 (2003).

de Carvalho Baptista, I. M. et al. Colonization of oropharynx and lower respiratory tract in critical patients: risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Arch. Oral Biol. 85, 64–69 (2018).

Cruz Martínez, C., Diaz Gómez, M. & Oh, M. S. Use of traditional herbal medicine as an alternative in dental treatment in Mexican dentistry: A review. Pharm. Biol. 55, 1992–1998 (2017).

Balto, H., Al-Sanie, I., Al-Beshri, S. & Aldrees, A. Effectiveness of Salvadora persica extracts against common oral pathogens. Saudi Dent. J. 29, 1–6 (2017).

Beveridge, T. J. Structures of gram-negative cell walls and their derived membrane vesicles. J. Bacteriol. 181, 4725–4733 (1999).

Husain, S. et al. Chitosan biomaterials for current and potential dental applications. Materials 10, 602 (2017).

Yan, Y. et al. Research progress on antimicrobial activities and mechanisms of natural alkaloids: A review. Antibiotics 10, 318 (2021).

Opara, L. U., Al-Ani, M. R. & Al-Shuaibi, Y. S. Physico-chemical properties, vitamin C content, and antimicrobial properties of pomegranate fruit (Punica granatum L.). Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2, 315–321 (2009).

Ahmad, A., Kaleem, M., Ahmed, Z. & Shafiq, H. Therapeutic potential of flavonoids and their mechanism of action against microbial and viral infections—A review. Food Res. Int. 77, 221–235 (2015).

Rao, A., Zhang, Y., Muend, S. & Rao, R. Mechanism of antifungal activity of terpenoid phenols resembles calcium stress and inhibition of the TOR pathway. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 5062–5069 (2010).

Montoya, S. C. N. et al. Natural anthraquinones probed as Type I and Type II photosensitizers: Singlet oxygen and superoxide anion production. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 78, 77–83 (2005).

Rashki, S. et al. Chitosan-based nanoparticles against bacterial infections. Carbohydr. Polym. 251, 117108 (2021).

Venkateswarulu, T. C. et al. Estimation of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of antimicrobial peptides of Saccharomyces boulardii against selected pathogenic strains. Karbala Int. J. Mod. Sci. 5, 8 (2019).

Faridha Begum, I., Mohankumar, R., Jeevan, M. & Ramani, K. GC–MS analysis of bio-active molecules derived from Paracoccus pantotrophus FMR19 and the antimicrobial activity against bacterial pathogens and MDROs. Indian J. Microbiol. 56, 426–432 (2016).

Adu, O. T. et al. Phytochemical screening and biological activities of Diospyros villosa (L.) De Winter Leaf and stem-bark extracts. Horticulturae 8, 945 (2022).

Pu, Z. et al. Antimicrobial activity of 9-Octadecanoic Acid-hexadecanoic acid-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diyl ester from neem oil. Agric. Sci. China 9, 1236–1240 (2010).

Bhat, R. S. et al. Trigonella foenum-graecum L. seed germination under sodium halide salts exposure. Fluoride 56(2), 169–179 (2023).

Bhat, R. S. et al. Biochemical and FT-IR profiling of Tritium aestivum L. seedling in response to sodium fluoride treatment. Fluoride 55(1), 81–89 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R179), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.B., A.E., S.A., N.M., and S.H.A. initiated and organized this study. M.B., S.H.A., and R.B. are involved in preparing samples/performing experiments. M.B., and R.B. interpreted data. H.B., A.E., S.A., R.B., and M.B. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Balto, H., Bekhit, M.S., Auda, S.H. et al. Synergistic effect of Salvadora persica and chitosan nanoparticles against oropharyngeal microorganisms. Sci Rep 14, 12997 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63636-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63636-1